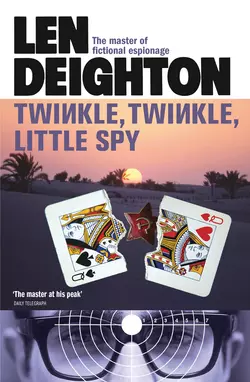

Twinkle Twinkle Little Spy

Len Deighton

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Шпионские детективы

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 682.75 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 18.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: A Soviet space scientist defects to win academic freedom, but western intelligence has other plans for him, and sends an unnamed spy – perhaps the same reluctant hero of The Ipcress File – to look after him. But what follows is a blood-streaked trail across three continents…