The Ipcress File

Len Deighton

Len Deighton’s classic first novel, whose protagonist is a nameless spy – later christened Harry Palmer and made famous worldwide in the iconic 1960s film starring Michael Caine.The Ipcress File was not only Len Deighton’s first novel, it was his first bestseller and the book that broke the mould of thriller writing.For the working class narrator, an apparently straightforward mission to find a missing biochemist becomes a journey to the heart of a dark and deadly conspiracy.The film of The Ipcress File gave Michael Caine one of his first and still most celebrated starring roles, while the novel itself has become a classic.

Cover designer’s note (#u37c70f8c-ea33-58d7-b651-83581325f7a6)

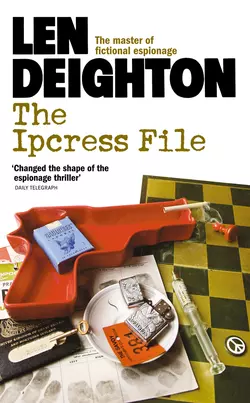

The great challenge I faced when asked to produce the covers for new editions of Len Deighton’s books was the existence of the brilliant designs conceived by Ray Hawkey for the original editions.

However, having arrived at a concept, part of the joy I derived in approaching this challenge was the quest to locate the various props which the author had so beautifully detailed in his texts. Deighton has likened a spy story to a game of chess, which led me to transpose the pieces on a chess board with some of the relevant objects specified in each book. I carried this notion throughout the entire quartet of books.

Since smoking was so much part of our culture during the Cold War era, I also set about gathering tobacco-related paraphernalia.

Each chapter of The Ipcress File opens with its Gauloises-smoking protagonist’s horoscope, so discovering an Aquarius cigarette lighter was a great coup. Finding a Gauloises cigarette packet, designed by Marcel Jacno in 1936, became a more difficult proposition. However, after much searching, I eventually found one via the Internet!

Serendipity sometimes plays an important part in the design process. In seeking an appropriate ashtray, to carry through the ‘smoking’ theme, I accidentally came across a unique piece shaped like a hand gun, so I aimed it at a red chess pawn, which represents Ipcress’s ‘Red’ Cold War antagonist.

The image of the gun pays homage to the original Hawkey-designed Ipcress jacket. I further retained the wooden type font logotype originated by him.

One of my long-time hobbies has been collecting cigarette cards. I was fortunate to find some appropriate images among my personal trove to illustrate the back cover, and these are accompanied by examples of military insignia gathered during my National Service days served in Cold War Korea!

Len Deighton and I shared a great affection for London’s Savoy Hotel. My father had served as a waiter there in the 1930s so I have a number of pieces of memorabilia from the Savoy, including the saucer and the cloakroom ticket depicted on the cover.

I was thrilled to locate the ‘Made in GDR’ syringe in Latvia, of all places. Closer to home, I have kept all my past British passports, together with most of my boarding passes and baggage labels. The Chubb key and the CND badge – which today has become a fashion accessory – came from other locations around the UK. The 1960s postage stamp on the spine of the cover commemorates the former Soviet spy, Richard Sorge.

During the 1970s, while designing a supplement series for the London Sunday Times, I needed a set of fingerprints to illustrate a specific article, so I persuaded the duty sergeant at my local police station to take mine, which are here given a new public airing!

I photographed the cover set-up using natural daylight, with my Canon OS 5D digital camera.

Arnold Schwartzman OBE RDI

LEN DEIGHTON

The Ipcress File

Copyright (#u37c70f8c-ea33-58d7-b651-83581325f7a6)

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd.

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain by Hodder & Stoughton 1962

Copyright © Pluriform Publishing Company BV 1962

Introduction copyright © Pluriform Publishing Company BV 2009

Cover designer’s note © Arnold Schwartzman 2009

Cover design and photography © Arnold Schwartzman 2009

Len Deighton asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins ebooks

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication

Source ISBN: 9780586026199

Ebook Edition © MARCH 2015 ISBN: 9780007343027

Version: 2017-08-10

And now I will unclasp a secret book, And to your quick-conceiving discontents, I’ll read you matter deep and dangerous.

Henry IV

Though it must be said that every species of birds has a manner peculiar to itself, yet there is somewhat in most genera at least that at first sight discriminates them, and enables a judicious observer to pronounce upon them with some certainty.

Gilbert White, 1778

Contents

Cover (#uc73c85da-1df8-5689-8c9c-bb28d5808765)

Cover designer’s note

Title Page (#u46e953ca-4c23-5ede-a01c-3a88be58db6c)

Copyright

Epigraph (#ua30b6bdd-22b2-5e89-94a0-9c7019cf670d)

Introduction

The Ipcress File: Secret File No. 1

Prologue

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Epilogue

Footnotes

Appendix

Keep Reading (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author

By Len Deighton

About the Publisher

Introduction (#u37c70f8c-ea33-58d7-b651-83581325f7a6)

The Ipcress File was my first attempt to write a book. I was a commercial artist, or ‘illustrator’ as we are now called. I had never been a journalist or reporter of any kind so I was unaware of how long writing a book was likely to take. Knowing the size of the task is a deterrent for many professional writers, which is why they defer their ambitions often until it is too late. Being unaware of what’s ahead can be an advantage. It shines a green light for everything from enlisting in the Foreign Legion to getting married.

So I stumbled into writing this book with a happy optimism that ignorance provides. Was it a depiction of myself? Well, who else did I have? After completing two and a half years of military service I had been, for three years, a student at St Martin’s School of Art in Charing Cross Road. I am a Londoner. I grew up in Marylebone and once art school started I rented a tiny grubby room around the corner from the art school. This cut my travelling time back to five minutes. I grew to know Soho very well indeed. I knew it by day and by night. I was on hello, how are you? terms with the ‘ladies’, the restaurateurs, the gangsters and the bent coppers. When, after some years as an illustrator, I wrote The Ipcress File much of its description of Soho was the observed life of an art student resident there.

After three years postgraduate study at the Royal College of Art I celebrated by impulsively applying for a job as flight attendant with British Overseas Airways. In those days this provided three or four days stop-over at the end of each short leg. I spent enough time in Hong Kong, Cairo, Nairobi, Beirut and Tokyo to make good and lasting friendships there. When I became an author, these background experiences of foreign people and places proved of lasting benefit.

I don’t know why or how I came to writing books. I had always been a dedicated reader; obsessional is perhaps the better word. At school, having proved to be a total dud at any form of sport – and most other things – I read every book in sight. There was no system to my reading, nor even a pattern of selection. I remember reading Plato’s The Republic with the same keen attention and superficial understanding as I read Chandler’s The Big Sleep and H.G. Wells’ The Outline of History and both volumes of The Letters of Gertrude Bell. I filled notebooks as I encountered ideas and opinions that were new to me, and I vividly remember how excited I was to discover that The Oxford Universal Dictionary incorporated thousands of quotations from the greatest of great writers.

So I wasn’t taking myself too seriously when, as a holiday diversion, I took a school exercise book and a fountain pen, and started this story. Knowing no other style I did it as though I was writing a letter to an old, intimate and trusted friend. I immediately fell into the first person style without knowing much about the literary alternatives.

My memory has always been unreliable, as my wife Ysabele regularly points out to me, but I am convinced that this first book was influenced by my time as the art director of an ultra-smart London advertising agency. I spent my days surrounded by highly educated, witty young men who had been at Eton together. We relaxed in leather armchairs in their exclusive Pall Mall clubs. We exchanged barbed compliments and jocular abuse. They were kind to me, and generous, and I enjoyed it immensely. Later, when I created WOOC(P), the intelligence service offices depicted here, I took the social atmosphere of that sleek and shiny agency and inserted it into some ramshackle offices that I once rented in Charlotte Street.

Using the first person narrative enabled me to tell the story in the distorted way that subjective memory provides. The hero does not tell the exact truth; none of the characters tell the exact truth. I don’t mean that they tell the blatant self-serving lies that politicians do, I mean that their memory tilts towards justification and self-regard. What happens in The Ipcress File (and in all my other first-person stories) is found somewhere in the uncertainty of contradiction. In navigation, the triangle where three lines of reference fail to intersect is call a ‘cocked hat’. My stories are intended to offer no more precision than that. I want the books to provoke different reactions from different readers (as even history must do to some extent).

Publication of The Ipcress File coincided with the arrival of the first of the James Bond films. My book was given very generous reviews and more than one of my friends was moved to confide that the critics were using me as a blunt instrument to batter Ian Fleming about the head. Even before publication day, I was taken by Godfrey Smith (a senior figure at The Daily Express newspaper) to lunch at the Savoy Grill. We discussed serial rights. The next day I went in my battered old VW Beetle to Pinewood Film Studios and lunch with the unforgettable and in every way astonishing Harry Saltzman. He had co-produced Dr No,which was getting widespread publicity, and had decided that The Ipcress File and its unnamed hero could provide a counterweight to the Bond series. On the way to Pinewood my car phone brought a request for an interview with Newsweek and there were similar requests from publications in Paris and New York. It was difficult to believe this was all really happening; illustrators were never treated like this. Never! I was nervously unbelieving, and constantly ready to wake up from this frantic dream. Between meetings and interviews I continued my work as a freelance illustrator. My friends delicately ignored my Jekyll and Hyde life, and so did the clients to whom I delivered my drawings. I didn’t feel like a writer, I felt like an impostor. I didn’t have those intense literary ambitions that writers are supposed to have while they languish in a cobwebbed garret.

Publication proved that I wasn’t the only one surprised by the book’s success. Despite the serialization and the entire hullabaloo, Hodder and Stoughton resolutely restricted their print order to 4,000 books. These were sold out in a couple of days. Reprinting took weeks and much of the value of the publicity and serialization was lost.

There was one question that remained unanswered. Why did I say that the hero was a northerner from Burnley? I truly have no idea. I had seen the destination ‘Burnley’ on parcels I had handled while on a Christmas vacation job at King’s Cross sorting office. I suppose that invention marked one tiny reluctance to depict myself exactly as I was.

Perhaps this spy fellow is not me after all.

Len Deighton, 2009

The Ipcress File (#u37c70f8c-ea33-58d7-b651-83581325f7a6)

PROLOGUE (#ulink_f7da6a4a-9539-57a3-9b8b-fcc8e1a974a5)

They came through on the hot

line at about half past two in the afternoon. The Minister didn’t quite understand a couple of points in the summary. Perhaps I could see the Minister.

Perhaps.

The Minister’s flat overlooked Trafalgar Square and was furnished like Oliver Messel did it for Oscar Wilde. He sat in the Sheraton, I sat in the Hepplewhite and we peeped at each other through the aspidistra plant.

‘Just tell me the whole story in your own words, old chap. Smoke?’

I was wondering whose words I might otherwise have used as he skimmed the aspidistra with his slim gold cigarette case. I beat him to the draw with a crumpled packet of Gauloises; I didn’t know where to begin.

‘I don’t know where to begin,’ I said. ‘The first document in the dossier …’

The Minister waved me down. ‘Never mind the dossier, my dear chap, just tell me your personal version. Begin with your first meeting with this fellow …’ he looked down to his small morocco-bound notebook, ‘Jay. Tell me about him.’

‘Jay. His code-name is changed to Box Four,’ I said.

‘That’s very confusing,’ said the Minister, and wrote it down in his book.

‘It’s a confusing story,’ I told him. ‘I’m in a very confusing business.’

The Minister said, ‘Quite,’ a couple of times, and I let a quarter inch of ash away towards the blue Kashan rug.

‘I was in Lederer’s about 12.55 on a Tuesday morning the first time I saw Jay,’ I continued.

‘Lederer’s?’ said the Minister. ‘What’s that?’

‘It’s going to be very difficult for me if I have to answer questions as I go along,’ I said. ‘If it’s all the same to you, Minister, I’d prefer you to make a note of the questions, and ask me afterwards.’

‘My dear chap, not another word, I promise.’

And throughout the entire explanation he never again interrupted.

1 (#ulink_01a4a1f1-13f1-5d0c-8a60-a66ea5edd6c7)

[Aquarius (Jan 20–Feb 19) A difficult day. You will face varied problems. Meet friends and make visits. It may help you to be better organized.]

I don’t care what you say, 18,000 pounds (sterling) is a lot of money. The British Government had instructed me to pay it to the man at the corner table who was now using knife and fork to commit ritual murder on a cream pastry.

Jay the Government called this man. He had small piggy eyes, a large moustache and handmade shoes which I knew were size ten. He walked with a slight limp and habitually stroked his eyebrow with his index finger. I knew him as well as I knew anyone, for I had seen film of him in a small, very private cinema in Charlotte Street, every day for a month.

Exactly one month previous I had never heard of Jay. My three weeks’ termination of engagement leave had sped to a close. I had spent it doing little or nothing unless you are prepared to consider sorting through my collection of military history books a job fit for a fully grown male. Not many of my friends were so prepared.

I woke up saying to myself ‘today’s the day’ but I didn’t feel much like getting out of bed just the same. I could hear the rain even before I drew the curtains back. December in London – the soot-covered tree outside was whipping itself into a frenzy. I closed the curtains quickly, danced across the icy-cold lino, scooped up the morning’s post and sat down heavily to wait while the kettle boiled. I struggled into the dark worsted and my only establishment tie – that’s the red and blue silk with the square design – but had to wait forty minutes for a cab. They hate to come south of the Thames you see.

It always had made me feel a little self-conscious saying, ‘War Office’ to cab drivers; at one time I had asked for the pub in Whitehall, or said ‘I’ll tell you when to stop,’ just to avoid having to say it. When I got out the cab had brought me to the Whitehall Place door and I had to walk round the block to the Horse Guards Avenue entrance. A Champ vehicle was parked there, a red-necked driver was saying ‘Clout it one’ to an oily corporal in dungarees. The same old army, I thought. The long lavatory-like passages were dark and dirty, and small white cards with precise military writing labelled each green-painted door: GS 3, Major this, Colonel that, Gentlemen, and odd anonymous tea rooms from which bubbly old ladies in spectacles appeared when not practising alchemy within. Room 134 was just like any other; the standard four green filing cabinets, two green metal cupboards, two desks fixed together face to face by the window, a half full one pound bag of Tate and Lyle sugar on the window-sill.

Ross, the man I had come to see, looked up from the writing that had held his undivided attention since three seconds after I had entered the room. Ross said, ‘Well now,’ and coughed nervously. Ross and I had come to an arrangement of some years’ standing – we had decided to hate each other. Being English, this vitriolic relationship manifested itself in oriental politeness.

‘Take a seat. Well now, smoke?’ I had told him ‘No thanks’ for two years at least twice a week. The cheap inlay cigarette box (from Singapore’s change alley market) with the butterflies of wood grain, was wafted across my face.

Ross was a regular officer; that is to say he didn’t drink gin after 7.30 P.M. or hit ladies without first removing his hat. He had a long thin nose, a moustache like flock wallpaper, sparse, carefully combed hair, and the complexion of a Hovis loaf.

The black phone rang. ‘Yes? Oh, it’s you, darling,’ Ross pronouncing each word with exactly the same amount of toneless indifference. ‘To be frank, I was going to.’

For nearly three years I had worked in Military Intelligence. If you listened to certain people you learned that Ross was Military Intelligence. He was a quiet intellect happy to work within the strict departmental limitations imposed upon him. Ross didn’t mind; hitting platform five at Waterloo with rosebud in the buttonhole and umbrella at the high port was Ross’s beginning to a day of rubber stamp and carbon paper action. At last I was to be freed. Out of the Army, out of Military Intelligence, away from Ross: working as a civilian with civilians in one of the smallest and most important of the Intelligence Units – WOOC(P).

‘Well, I’ll phone you if I have to stay Thursday night.’

I heard the voice at the other end say, ‘Are you all right for socks?’

Three typed sheets of carbon copies so bad I couldn’t read them (let alone read them upside down) were kept steady and to hand by the office tea money. Ross finished his call and began to talk to me, and I twitched facial muscles to look like a man paying attention.

He located his black briar pipe after heaping the contents of his rough tweed jacket upon his desk top. He found his tobacco in one of the cupboards. ‘Well now,’ he said. He struck the match I gave him upon his leather elbow patch.

‘So you’ll be with the provisional people.’ He said it with quiet distaste; the Army didn’t like anything provisional, let alone people, and they certainly didn’t like the WOOC(P), and I suppose they didn’t much like me. Ross obviously thought my posting a very fine tentative solution until I could be got out of his life altogether. I won’t tell you all Ross said because most of it was pretty dreary and some of it is still secret and buried somewhere in one of those precisely but innocuously labelled files of his. A lot of the time he was having ignition trouble with his pipe and that meant he was going to start the story all through again.

Most of the people at the War House, especially those on the intelligence fringes as I was, had heard of the WOOC(P) and a man called Dalby. His responsibility was direct to the Cabinet. Envied, criticized and opposed by other intelligence units Dalby was almost as powerful as anyone gets in this business. People posted to him ceased to be in the Army for all practical purposes and they were removed from almost all War Office records. In the few rare cases of men going back to normal duty from WOOC(P) they were enlisted all over afresh and given a new serial number from the batch that is reserved for Civil Servants seconded to military duties. Pay was made by an entirely different scale, and I wondered just how long I would have to make the remnants of this month’s pay last before the new scale began.

After a search for his small metal-rimmed army spectacles, Ross went through the discharge rigmarole with loving attention to detail. We began by destroying the secret compensation contract that Ross and I had signed in this very room almost three years ago and ended by his checking that I had no mess charges unpaid. It had been a pleasure to work with me, Provisional was clever to get me, he was sorry to lose me and Mr Dalby was lucky to have me and would I leave this package in Room 225 on the way out – the messenger seemed to have missed him this morning.

Dalby’s place is in one of those sleazy long streets in the district that would be Soho, if Soho had the strength to cross Oxford Street. There is a new likely-looking office conversion wherein the unwinking blue neon glows even at summer midday, but this isn’t Dalby’s place. Dalby’s department is next door. His is dirtier than average with a genteel profusion of well-worn brass work, telling of the existence of ‘The Ex-Officers’ Employment Bureau. Est 1917’; ‘Acme Films Cutting Rooms’; ‘B. Isaacs. Tailor – Theatricals a Speciality’; ‘Dalby Inquiry Bureau – staffed by ex-Scotland Yard detectives’. A piece of headed notepaper bore the same banner and the biro’d message, ‘Inquiries third floor, please ring.’ Each morning at 9.30 I rang, and avoiding the larger cracks in the lino, began the ascent. Each floor had its own character – ageing paint varying from dark brown to dark green. The third floor was dark white. I passed the scaly old dragon that guarded the entrance to Dalby’s cavern.

I’ll always associate Charlotte Street with the music of the colliery brass bands that I remember from my childhood. The duty drivers and cipher clerks had a little fraternity that sat around in the dispatch office on the second floor. They had a very loud gramophone and they were all brass band fanatics; that’s a pretty esoteric failing in London. Up through the warped and broken floorboards came the gleaming polished music. Fairey Aviation had won the Open Championship again that year and the sound of the test piece reached through to every room in the building. It made Dalby feel he was overlooking Horse Guards Parade; it made me feel I was back in Burnley.

I said ‘Hello, Alice,’ and she nodded and busied herself with a Nescafé tin and a ruinous cup of warm water. I went through to the back office, saw Chico – he’d got a step beyond Alice, his Nescafé was almost dissolved. Chico always looked glad to see me. It made my day; it was his training, I suppose. He’d been to one of those very good schools where you meet kids with influential uncles. I imagine that’s how he got into the Horse Guards and now into WOOC(P) too, it must have been like being at school again. His profusion of long lank yellow hair hung heavily across his head like a Shrove Tuesday mishap. He stood 5ft 11in in his Argyll socks, and had an irritating physical stance, in which his thumbs rested high behind his red braces while he rocked on his hand-lasted Oxfords. He had the advantage of both a good brain and a family rich enough to save him using it.

I walked right through the Dalby Inquiry Bureau and down the back stairs. For this whole house belonged to WOOC(P) even though each business on each floor had its own ‘front’ for our convenience. By 9.40 A.M. each morning I was in the small ramshackle projection room of Acme Films.

The sickly sweet smell of film cement and warm celluloid was so strong that I think they must have sprayed it around. I threw my English B-picture raincoat across a pile of film tins, clean side up, and sank into one of the tip-up cinema seats. As always it was seat twenty-two, the one with the loose bolt, and always by that time I didn’t feel much like moving.

The Rheostat made that horrible squeaking noise. The room lights dimmed tiredly and the little projector clattered into action. A screaming white rectangle flung animated abstract shapes of scratch marks at my eyes, then darkened to a business-like grey flannel suit colour.

In crude stick-on letters the film title said JAY. LEEDS. WARREN THREE. (Warren Three was the authority upon which it was filmed.) The picture began. Jay was walking along a crowded pavement. His moustache was gigantic, but cultivated with a care that he gave to everything he did. He limped, but it certainly didn’t impair his progress through the crowd. The camera wobbled and then tracked swiftly away. The van in which the movie camera had been hidden had been forced to move faster than Jay by the speed of the traffic. The screen flashed white and the next short, titled length began. Some of the films showed Jay with a companion, code-named HOUSEMARTIN. He was a six feet tall handsome man in a good-quality camel-hair overcoat. His hair was waved, shiny and a little too perfectly grey at the temples. He wore a handful of gold rings, a gold watch strap and a smile full of jacket crowns. It was an indigestible smile – he was never able to swallow it.

Chico operated the projector with tongue-jutting determination. Once in a while he would slip into the programme one of those crisp Charing Cross Road movies that feature girls in the skin. It was Dalby’s idea to keep his ‘students’ awake during these viewings.

‘Know your enemies,’ was Dalby’s theory. He felt if all his staff knew the low-life of the espionage business visually they would stand a better chance of predicting their thought. ‘Because he had a picture of Rommel over his bed Montgomery won Alamein.’ I don’t necessarily believe this – but this was what Dalby kept saying. (Personally I ascribe a lot of value to those extra 600 tanks.)

Dalby was an elegant languid public school Englishman of a type that can usually reconcile his duty with comfort and luxury. He was a little taller than I am: probably 6ft 1in or 6ft 2in. He had long fine hair, and every now and then would grow a little wispy blond moustache. At present he didn’t have it. He had a clear complexion that sunburnt easily and very small puncture-type scar tissue high on the left cheek to prove he had been to a German University in ’38. It had been a useful experience, and in 1941 enabled him to gain a DSO and bar. A rare event in any Intelligence group but especially in the one he was with. No citations of course.

He was unpublic school enough to wear a small signet ring on his right hand, and whenever he pulled at his face, which was often, he dragged the edge of the ring against the skin. This produced a little red weal due to excessive acidity in the skin. It was fascinating.

He peeped at me over the toes of his suède shoes which rested in the centre of a deskful of important papers, arranged in precise heaps. Spartan furniture (Ministry of Works, contemporary) punctured the cheap lino and a smell of tobacco ash was in the air.

‘You are loving it here of course?’ Dalby asked.

‘I have a clean mind and a pure heart. I get eight hours’ sleep every night. I am a loyal, diligent employee and will attempt every day to be worthy of the trust my paternal employer puts in me.’

‘I’ll make the jokes,’ said Dalby.

‘Go ahead,’ I said. ‘I can use a laugh – my eyes have been operating twenty-four frames per second for the last month.’

Dalby tightened a shoe-lace. ‘Think you can handle a tricky little special assignment?’

‘If it doesn’t demand a classical education I might be able to grope around it.’

Dalby said, ‘Surprise me, do it without complaint or sarcasm.’

‘It wouldn’t be the same,’ I said.

Dalby swung his feet to the floor and became deliberate and serious. ‘I’ve been across to the Senior Intelligence Conference this morning. Home Office are worried sick about these disappearances of their top biochemists. Committees, subcommittees – you should have seen them over there, talk about Mother’s Day at the Turkish Bath.’

‘Has there been another then?’ I asked.

‘This morning,’ said Dalby, ‘one left home at 7.45 A.M., never reached the lab.’

‘Defection?’ I asked.

Dalby pulled a face and spoke to Alice over the desk intercom, ‘Alice, open a file and give me a code-name for this morning’s “wandering willie”.’ Dalby made his wishes known by peremptory unequivocal orders; all his staff preferred them to the complex polite chat of most Departments as especially did I as a refugee from the War Office. Alice’s voice came over the intercom like Donald Duck with a head cold. To whatever she said Dalby replied, ‘The hell with what the letter from the Home Office said. Do as I say.’

There was a moment or so of silence then Alice used her displeased voice to say a long file number and the code-name RAVEN. All people under long-term surveillance had bird names.

‘That’s a good girl,’ said Dalby in his most charming voice and even over the squawk-box I could hear the lift in Alice’s voice as she said, ‘Very good, sir.’

Dalby switched off the box and turned back to me. ‘They have put a security blackout on this Raven disappearance but I told them that William Hickey will be carrying a photo of his dog by the midday editions. Look at these.’ Dalby laid five passport photos across his oiled teak desk. Raven was a man in his late forties, thick black hair, bushy eyebrows, bony nose – there were a hundred like him in St James’s at any minute of the day. Dalby said, ‘It makes eight top rank Disappearances in …’ he looked at his desk diary, ‘… six and a half weeks.’

‘Surely Home Office aren’t asking us to help them,’ I said.

‘They certainly are not,’ said Dalby. ‘But if we found Raven I think the Home Secretary would virtually disband his confused little intelligence department. Then we could add their files to ours. Think of that.’

‘Find him?’ I said. ‘How would we start?’

‘How would you start?’ asked Dalby.

‘Haven’t the faintest,’ I said. ‘Go to laboratory, wife doesn’t know what’s got into him lately, discover dark almond-eyed woman. Bank manager wonders where he’s been getting all that money. Fist fight through darkened lab. Glass tubes that would blow the world to shreds. Mad scientist backs to freedom holding phial – flying tackle by me. Up grams Rule Britannia.’

Dalby gave me a look calculated to have me feeling like an employee, he got to his feet and walked across to the big map of Europe that he had had pinned across the wall for the last week. I walked across to him. ‘You think that Jay is master minding it,’ I said. Dalby looked at the map and still staring at it said, ‘Sure of it, absolutely sure of it.’

The map was covered with clear acetate and five small frontier areas from Finland to the Caspian were marked in black greasy pencil. Two places in Syria carried small red flags.

Dalby said, ‘Every important illegal movement across these bits of frontier that I have marked are with Jay’s OK.

‘Important movement. I don’t mean he stands around checking that the eggs have little lions on.’ Dalby tapped the border. ‘Somewhere before they get him as far as this we must …’ Dalby’s voice trailed away lost in thought.

‘Hi-jack him?’ I prompted softly. Dalby’s mind had raced on. ‘It’s January. If only we could do this in January,’ he said. January was the month that the Government estimates were prepared. I began to see what he meant. Dalby suddenly became aware of me again and turned on a big flash of boyish charm.

‘You see,’ said Dalby. ‘It’s not just a case of the defection of one biochemist …’

‘Defection? I thought that Jay’s speciality was a high-quality line in snatch jobs.’

‘Hi-jack! Snatch jobs! all that gangland talk. You read too many newspapers that’s your trouble. You mean they walk him through the customs and immigration with two heavy-jowled men behind him with their right hands in their overcoat pockets? No. No. No,’ he said the three ‘noes’ softly, paused and added two more. ‘… this isn’t a mere emigration of one little chemist,’ (Dalby made him sound like an assistant from Boots) ‘who has probably been selling them stuff for years. In fact given the choice I’m not sure I wouldn’t let him go. It’s those—people at the Home Office. They should know about these things before they occur: not start crying in their beer afterwards.’ He picked two cigarettes out of his case, threw one to me and balanced the other between his fingers. ‘They are all right running the Special Branch, HM prisons and Cruelty to Animal Inspectors but as soon as they get into our business they have trouble touching bottom.’

Dalby continued to do balancing tricks with the cigarette to which he had been talking. Then he looked up and began to talk to me. ‘Do you honestly believe that given all the Home Office Security files we couldn’t do a thousand times better than they have ever done?’

‘I think we could,’ I said. He was so pleased with my answer that he stopped toying with the cigarette and lit it in a burst of energy. He inhaled the smoke then tried to snort it down his nostrils. He choked. His face went red. ‘Shall I get you a glass of water?’ I asked, and his face went redder. I must have ruined the drama of the moment. Dalby recovered his breath and went on.

‘You can see now that this is something more than an ordinary case, it’s a test case.’

‘I sense impending Jesuitical pleas.’

‘Exactly,’ said Dalby with a malevolent smile. He loved to be cast as the villain, especially if it could be done with schoolboy-scholarship. ‘You remember the Jesuit motto.’ He was always surprised to find I had read any sort of book.

‘When the end is lawful the means are also lawful,’ I answered.

He beamed and pinched the bridge of his nose between finger and thumb. I had made him very happy.

‘If it pleases you that much,’ I said, ‘I’m sorry I can’t muster it in dog-Latin.’

‘It’s all right, all right,’ said Dalby. He traversed his cigarette then changed the range and elevation until it had me in its sights. He spoke slowly, carefully articulating each syllable. ‘Go and buy this Raven for me.’

‘From Jay.’

‘From anyone who has him – I’m broadminded.’

‘How much can I spend, Daddy?’

He moved his chair an inch nearer the desk with a loud crash. ‘Look here, every point of entry has the stopper jammed tightly upon it.’ He gave a little bitter laugh. ‘It makes you laugh, doesn’t it. I remember when we asked HO to close the airports for one hour last July. The list of excuses they gave us. But when someone slips through their little butter-fingers and they are going to be asked some awkward questions, anything goes. Anyway, Jay is a bright lad; he’ll know what’s going on; he’ll have this Raven on ice for a week and then move him when all goes quiet. If meanwhile we make him anything like a decent offer …’ Dalby’s voice trailed off as he slipped his mind into over-drive, ‘… say 18,000 quid. We pick him up from anywhere Jay says – no questions asked.’

‘18,000,’ I said.

‘You can go up to twenty-three if you are sure they are on the level. But on our terms. Payment after delivery. Into a Swiss bank. Strictly no cash and I don’t want Raven dead. Or even damaged.’

‘OK,’ I said. I suddenly felt very small and young and called upon to do something that I wasn’t sure I could manage. If this was the run of the mill job at WOOC(P) they deserved their high pay and expense accounts. ‘Shall I start by locating Jay?’ It seemed a foolish thing to say but I felt in dire need of an instruction book.

Dalby flapped a palm. I sat down again. ‘Done,’ he said. He flipped a switch on his squawk-box. Alice’s voice, electronically distorted, spoke from the room downstairs. ‘Yes, sir,’ she said.

‘What’s Jay doing?’

There was a couple of clicks and Alice’s voice came back to the office again. ‘At 12.10 he was in Lederer’s coffee-house.’

‘Thanks, Alice,’ said Dalby.

‘Cease surveillance, sir?’

‘Not yet, Alice. I’ll tell you when.’ To me he said, ‘There you are then. Off you go.’

I doused my cigarette and stood up. ‘Two other last things,’ said Dalby. ‘I am authorizing you for 1,200 a year expenses. And,’ he paused, ‘don’t contact me if anything goes wrong, because I won’t know what the hell you are talking about.’

2 (#ulink_1d607d52-d0c2-5fe1-a491-8fd3115b00ee)

[Aquarius (Jan 20–Feb 19) New business opportunities begin well in unusual surroundings that provide chance of a gamble.]

I walked down Charlotte Street towards Soho. It was that sort of January morning that had enough sunshine to point up the dirt without raising the temperature. I was probably seeking excuses to delay; I bought two packets of Gauloises, sank a quick grappa with Mario and Franco at the Terrazza, bought a Statesman, some Normandy butter and garlic sausage. The girl in the delicatessen was small, dark and rather delicious. We had been flirting across the mozzarella for years. Again we exchanged offers with neither side taking up the option.

In spite of my dawdling I was still in Lederer’s coffee-house by 12.55. Led’s is one of those continental-style coffee-houses where coffee comes in a glass. The customers, who mostly think of themselves as clientele, are those smooth-rugged characters with sun-lamp complexions, half a dozen 10in by 8in glossies, an agent and more time than money on their hands.

Jay was there, skin like polished ivory, small piggy eyes and a luxuriant growth of facial hair. Small talk ricocheted around me as reputations hit the dust.

‘She’s marvellous in small parts,’ an expensive gingery-pink rinse was saying, and people were dropping names, using one-word abbreviations of West End shows and trying to leave without paying for their coffee.

The back of Jay’s large head touched the red flocked wallpaper between the notice that told customers not to expect dairy cream in their pastries and the one that cautioned them against passing betting slips. Jay had seen me, of course. He’d priced my coat and measured the pink-haired girl in the flick of an eyelid. I waited for Jay to stroke his eyebrow with his right index finger and I knew that he would. He did. I’d never seen him before but I knew him from the flick of the finger to the lopsided way he walked downstairs. I knew that he’d paid sixty guineas for each of his suits except the flannel one, which by some quirk of a tailor’s reasoning had cost fifty-eight and a half guineas. I knew all about Jay except how to ask him to sell me a biochemist for £18,000.

I sat down and burnt my raincoat on the bars of the fire. An unassisted thirty-eight with a sneer under contract eased her chair three-sixteenths of an inch to give me more space, and nosed deeper into Variety. She hated me because I was trying to pick her up, or not trying perhaps, but anyway, she had her reasons. On the far side of Jay’s table I saw the handsome face of Housemartin, his co-star in the Charlotte Street film library. I lit a Gauloise and blew a smoke ring. The thirty-eight sucked her teeth. I noticed Housemartin lean across to Jay and whisper in his ear while they both looked at me. Then Jay nodded.

The waitress – a young fifty-three with imitation pastry cream on her pinafore – came across to my table. My friend with Variety stretched out a hand, white and lifeless like some animal that had never been exposed to daylight. It touched the glass of cold coffee and dragged it away from the waitress. I ordered Russian tea and apple strudel.

Had it been Chico sitting there he would have been making time with the minox camera, and dusting the waitress for Jay’s prints, but I knew we had more footage on Jay than MGM have on Ben Hur, so I sat tight and edged into the strudel.

When I had finished my tea and bun I had no further excuse for delay. I searched through my pockets for some visiting cards. There was an engraved one that said ‘Bertram Loess – Assessor and Valuer’, another printed one that said ‘Brian Serck Inter News Press Agency’, and a small imitation leather folder that gave me Right of Entry under the Factories Act because I was a weights and measures inspector. None of those suited the present situation so I went across to Jay’s table, touched a forelock and said the first thing that came into my head – ‘Beamish,’ I said, ‘Stanley Beamish.’ Jay nodded. It was the head of a Buddha coming unsoldered. ‘Is there somewhere we can talk?’ I said. ‘I have a financial proposition to put to you.’ But Jay was not going to be hurried; he took out his thin wallet, produced a white rectangle and passed it to me. I read – ‘Henry Carpenter – Import Export’. I’d always favoured foreign names on the ground that there is nothing more authentically English than a foreign name. Perhaps I should tell Jay. He picked up his card and delicately with his big scarred finger-tips on the points returned it to his crocodile-skin wallet. He consulted a watch with a dial like the control panel of a Boeing 707, and eased himself back in his chair.

‘You shall take me to lunch,’ said Jay, as though he were conferring a favour.

‘I can’t,’ I said. ‘I have three months’ back pay outstanding and my expense account was only confirmed this morning.’ Jay was thunderstruck at striking this rich vein of honesty. ‘How much,’ said Jay. ‘How much is your expense account?’

‘1,200,’ I said.

‘A year?’ said Jay.

‘Yes,’ I said.

‘Not enough,’ said Jay, and he jabbed my chest to emphasize it. ‘Ask them for 2,000 at least.’

‘Yes,’ I said obediently. I didn’t think Dalby would stand for it, but there seemed no point in contradicting Jay at this stage of the proceedings.

‘I know somewhere very cheap,’ said Jay. As I saw it, a finer way out of the situation was for Jay to buy me lunch, but I know that this never even occurred to him. We all paid our bills, and I picked up my groceries, and then the three of us trailed out along Wardour Street, Jay in the lead. The lunch hour in Central London – the traffic was thick and most of the pedestrians the same. We walked past grim-faced soldiers in photo-shop windows. Stainless-steel orange squeezers and moron-manipulated pin-tables metronoming away the sunny afternoon in long thin slices of boredom. Through wonderlands of wireless entrails from the little edible condensers to gutted radar receivers for thirty-nine and six. On, shuffling past plastic chop suey, big-bellied naked girls and ‘Luncheon Vouchers Accepted’ notices, until we paused before a wide illustrated doorway – ‘Vicki from Montmartre’ and ‘Striptease in the Snow’ said the freshly-painted signs. ‘Danse de Desir – Non Stop Striptease Revue’ and the little yellow bulbs winked lecherously in the dusty sunlight.

We went inside. Jay was smiling and tapping Housemartin on the nose and the usherette on the bottom at the same time. The manager gave me a close scrutiny but decided I wasn’t from West End Central. I suppose I didn’t look wealthy enough.

I closed my eyes for a moment to accustom myself to the dark. On my left was a room with about sixty seats and a stage as big as a fireplace – it looked a slum in total darkness. I’d hate to see it with a window open.

In the cardboard proscenium a fat girl in black underwear was singing a song with the mad abandon that fitted 2.10 P.M. on a Tuesday afternoon.

‘We’ll wait here,’ said the handsome Housemartin, and Jay went up the staircase near the sign that said – ‘Barbarossa – club members only’ – and an arrow pointing upwards. We waited – you wouldn’t have thought that I was trying to do an £18,000 deal. The garlic sausage, the Statesman, the Normandy butter, had become a malleable shapeless lump. I didn’t think Dalby would wear that on my expenses, so I decided to hang on to it a little longer. Drums rolled, cymbals ‘zinged’, lights and gelatines clicked and clattered. Girls came on and went off. Girls thin, fat, tall and short. Girls in various stages of dress and undress; pink girls and green girls, little girls and old girls, and still more girls, relentlessly. Housemartin seemed to like it.

Finally he went to the gents, excusing himself with one of the less imaginative vulgarisms. A cigarette-girl, clad in a handful of sequins, tried to sell me a souvenir programme. I’d seen better print jobs on winkle bags, but then it was only costing twelve and six, and it was made in England. She offered me a pink felt Pluto, too. I declined gratefully. She sorted through the other things on the tray. ‘I’ll have a packet of Gauloises,’ I said. She smiled a crooked little smile – her lipstick was lopsided – she seemed to have very little skill at putting things on. She dropped her head to grope for the cigarettes. ‘Do you know what the packet looks like?’ she said. I helped her look. While her head was close to mine she said, in her pinched Northumberland accent, ‘Go home. There’s nothing to be gained here.’ She found the cigarettes and gave them to me. I gave her a ten-shilling note. ‘Thanks,’ she said, offering no change.

‘Not at all,’ I said. ‘Thank you.’ I watched her as she made her journey through the wispy audience of middle-aged tycoons. When she reached the rear of the auditorium she sold something to a plump man at the bar. She moved on out of my range of vision.

I looked around me; no one seemed to be watching. I walked up the stairs. It was all velveteen and tinsel stars. There was only one door on this landing – it was locked. I went up another floor. A notice said, ‘Private – Staff Only’; I pushed through the swing door. There was a long corridor ahead of me. Four doors opened to the right. None to the left. I opened the first door. It was a toilet. It was empty. The next door in the line-up said ‘Manager’; I tapped and opened it. There was a comfortable office: half a dozen bottles of booze, large armchair, a studio couch. A television set said ‘… begin to feel the tummy muscles stretching and relaxing …’

There was no one there. I walked across to the window. In the street below a man with a barrow was arranging the fruit best side forward. I went down the corridor and opened the next door – there was a complex and fleshy array of about twenty semi-nude chorus girls, changing their tiny costumes. A loudspeaker brought the sound of the piano and drums from downstairs. No one screamed, one or two of the girls looked up and then continued with their conversation. I closed the door quietly and went to the last door.

It was a large room devoid of any furniture; the windows were blocked up. From a loudspeaker came the same piano and drums. In the floor of the room were six panels of armour glass. The light came from the room below. I walked to the nearest glass panel and looked down through it. Below me was a small green baize table with sealed packs of cards, and ashtrays, and four gold-painted chairs. I walked to the centre of the room. The glass panels here were bigger. I looked down upon clean bright yellow and red numbers demarking black rectangles on the green felt. Inset into the table a nice new roulette wheel twinkled merrily. There was no sign of anyone unless you included the pale man in dark jacket and pin-stripe trousers who was lying full length along the gaming table. It looked like, and it just had to be; Raven.

3 (#ulink_c5ab6782-8708-5ca1-b0bb-810cfd4d5b33)

[Aquarius (Jan 20–Feb 19) You may be relying too heavily on other people’s intentions and ideas. A complete change will do you good.]

There was no other door to the room and the windows were blocked. I went back along the corridor and down the stairs. I tried the door again as I had on the way up; I reached the same conclusion. I moved it gently and heard the bolt rattle. I rapped it with my knuckles – it was solid. I went upstairs quickly and back into the observation room. From below the glass would look like mirror, but anyone in this room could see the cards all the players were holding.

I hadn’t yet offered a deal to Jay. If that was Raven I was bound to recover him, seize him, or whatever the terminology is. I went quickly back to the manager’s office. The woman on the TV was saying ‘… down together …’ I lifted his heavy typewriter off his desk and carried it along the corridor. Two girls in scanties came pushing out of the dressing-room and, seeing me, the tall one called through the doorway, ‘Watch your pockets girls, he’s back again,’ and her friend said, ‘He must be a reporter,’ and they both giggled and ran downstairs. I humped the huge typewriter into the observation room in time to see a figure enter the gaming room downstairs. It was Housemartin, and he now had a grease stain on the lapel of his camel-hair coat. He looked as hot and bothered as I felt, and he hadn’t had my troubles with the typewriter or the girls.

Housemartin was a big man. Because he wore suits with shoulders six inches outboard of the shoulder bone didn’t mean that he wasn’t beefy enough already. He picked the limp Raven off the big crème de menthe coloured table like a Queen’s scout with a rucksack, and marched off through the far door. I was groaning under the weight of the Olivetti and now I let go. It went through the big six-foot panel without a ripple. The surface shattered into a white opacity except for a large round hole through which I saw the typewriter hit the roulette wheel dead centre and continue its downward path to the floor – the hole in the gaming table mouthed its circular surprise. I kicked the splintery edges of the broken glass but still tore the seat of my trousers as I slid through the panel and dropped on to the gaming table below. I picked myself up and rubbed the torn place in my trousers. Suddenly the music from the loudspeaker ceased, and I heard one of the strippers running upstairs shouting.

Over the loudspeakers a voice said, ‘Ladies and Gentlemen, the police are checking the premises; please remain in your seats …’ By that time I was across the gaming room and through the doorway through which Housemartin and Raven had gone. I went down the stone staircase two steps at a time. There were two doorways, one had ‘emergency exit’ painted on it. I put my weight against the crunch-bars and opened it a couple of inches. I was in a semi-basement. There were four uniformed policemen standing ten feet away along the pavement. I closed the door and tried the other door. It opened. Inside were three middle-aged men in business suits. One was flushing the contents of his pockets down the toilet. One was standing in another toilet helping the third through a very small window. The sight through this window of the point of a blue helmet had me moving back up the stairs again. I had passed a door on the way down. I pushed at it now. It was made of metal, and was very heavy. It moved slowly and I found myself in an alley full of bent dustbins, wet cardboard cartons and crates with ‘No deposit’ stencilled upon them. At the end of the alley was a tall gate with a chain and padlock. Facing me was another metal door. I walked through it into a man in a greasy white jacket shouting ‘Make it spaghetti and chips twice.’ He looked me over suspiciously and said, ‘You want a meal?’

‘Yes,’ I said quickly

‘That’s all right then, sit down. I’m not doing no more coffee except with food.’ I nodded. ‘I take your order in a minute,’ he said.

I sat down and felt in my pocket for cigarettes. I had three and a half packets in one pocket and a quarter of a pound of garlic sausage, and a soft metal foil parcel of butter in the other. It was then that I discovered there a brand new hypodermic syringe in a black cardboard box, and I thought, ‘What did that cigarette-girl mean by “Go home. There is nothing to be gained here”?’

4 (#ulink_93f57c33-6a6d-5184-b9ac-4e49cb3a0234)

I used the emergency number to go through to our secret exchange: Ghost – which was our section of the special Government telephone exchange: Federal.

Ghost switchboard gave the usual eighty seconds of ‘Number unobtainable’ signal – to deter callers who dialled it by accident – then I gave the week’s code-words ‘MICHAEL’S BIRTHDAY’, and was connected to the duty officer. He plugged me in to Dalby who might have been anywhere – half-way across the world, perhaps. I conveyed the situation to him without going into details. He felt it was all his fault, and said how pleased he was that I hadn’t got mixed up with the ‘blue pointed head mob’. ‘You will be doing a job with me next week. It might be very tricky.’

‘Fine,’ I said.

‘I’ll speak to Alice about it, meanwhile I want you to change your papers.’ He rang off. I went home to a garlic sausage sandwich. ‘1,200,’ I thought. ‘That’s twenty-four pounds a week.’

‘Changing papers’ is a long and dreary process.

It meant photographs, documents, finger-prints and complications. A small roomful of civilian clerks at the War Office are busy the whole year through, doing nothing else. On Thursday I went to the little room at the top of the building to the department run by Mr Nevinson. On the door the small white ticket in its painted frame said, ‘Documents. Personnel Reclassifications and Personnel deceased’. Mr Nevinson and his colleagues have the highest security clearance of anyone in government employ and, as they all know very well, they are under continuous security surveillance. Through these hands at some time or other go papers for every important agent in HM Govt employ.

For example; take the time my picture appeared in The Burnley Daily Gazette in July 1939, when I won the fifth form mathematics prize; the following year the whole of the sixth appeared in a class photograph. If you try to see those issues now at the library, at the offices of The Burnley Daily Gazette, or at Colindale even, you’ll discover the thoroughness of Mr Nevinson. When your papers are changed your whole life is turned over like top-soil; new passport of course, but also new birth-certificate, radio and TV licences, marriage-certificates; and all the old ones are thoroughly destroyed. It takes four days. Today Mr Nevinson was starting on me.

‘Look at the camera, thank you. Sign here, thank you; and here, thank you; and again here, thank you; thumbs together, thank you; fingers together, thank you; now altogether, thank you; now you can wash your hands, thank you. We’ll be in touch. Soap and towel on the filing cabinet!’

5 (#ulink_3cc4acf3-e1c6-5688-83bc-c958749a7075)

[Aquarius (Jan 20–Feb 19) Don’t make hasty decisions about a prospect you have in mind. A difference of opinion may provide a chance for a journey.]

Monday I got to Charlotte Street usual time. A little grey rusting Morris 1000 knelt at the kerb, Alice at the controls. I was pretending I hadn’t seen her when she called out to me. I got into the car, the motor revved, away we went. We drove in silence a little way when I said, ‘I can’t find the bag of wet cement to put my feet into.’ She turned and cracked her make-up a little. Encouraged, I asked her where we were going.

‘To bait a Raven trap, I believe,’ she said.

There seemed no answer to that. After a few minutes she spoke again. ‘Look at this,’ she said, handing me a felt toy exactly like the one I had declined to buy in the strip club the week before. ‘There.’ She jabbed a finger while driving, talking and tuning the car radio. I looked at the pink spotted felt dog; some stuffing was coming out of its head. I prodded it around. ‘You’re looking for this?’ Alice had a Minox in her hand. She gave me a sour look, or perhaps I already had one.

‘I was pretty stupid …’ I said.

‘Try not to stay that way,’ she almost smiled. If she went on that way she’d soon have a crackle finish.

In Vauxhall Bridge Road we pulled into the kerb behind a black Rover car. Alice gave me a buff envelope about 10in by 6in and ¾in thick sealed with wax, and opened the door. I followed her. She ushered me into the rear seat of the Rover. The driver had a short haircut, white shirt, black tie and navy blue DB raincoat. Alice smacked the roof of the car with the flat of her hand; show jumper style. The car pulled away through the ‘back doubles’ of Victoria. I opened the buff envelope. Inside was a new passport, thumbed, bent and back-dated to look old; two keys; a sheet of paper with typing on it; three passport photos, and one of those multi-leaved airline tickets. I was booked BOAC first-class single LON/BEI. The typewritten sheet gave plane times and said, – ‘BA712. LAP 11.25. Beirut International Airport 20.00. Photo Identity: RAVEN. Juke box. Upstairs. BEI Airport. Destroy by burning immediately.’ It gave no date. Attached to one key was a number: ‘025.’ I looked at the man in the photos, then burned the typewritten sheets and the photos, and lit a cigarette.

We turned left out of Beauchamp Place on to the all too lavishly tended stretch of road that connects Maidenhead with Harrods. The driver’s first words were spoken at the Airport. ‘The overnight lockers are across the hall,’ he said.

I left the car and driver, and fitted my key into 025, one of a wall-full of metal twenty-four-hour lockers. It swung open and I left the key in the lock. Inside was a dark leather brief-case and a blue canvas zip bag with bulging side pockets. I took them across the hall to check in for my flight.

‘Is this all your baggage, sir?’ She weighed in my wardrobe case, took my ticket, straightened her strap, fluttered her eyelids and gave me a boarding card.

I took my brief-case, walked to the bookstall, bought New Statesman, Daily Worker and History Today, then took off towards my Exit. A bundle of people surged around kissing and greeting and ‘how lovelying’ their way across from the customs. In a dirty raincoat, hemmed in every-which-way was Ross. I didn’t want to see him, and it was mutual, but for a moment the crowd forced us together like unconnected elements among so many molecular constructions. I beamed at him – I knew this would irritate him most.

Through the big shed-like customs hall.

The BOAC girl called the flight in a resonant metallic voice – ‘BOAC announce the departure of flight BA712 to …’ We walked across the apron. The aeroplane had swarms of white garbed engineers and loaders in blue battledress making like busy past the airport policeman. I clanked up the steps.

There was that smell of blue upholstery and fan-heated ovens. A steward took my name, boarding card and dirty trench coat and I moved up front with my fellow first-class passengers, towards a flurried-looking hostess who’d just done a four-minute mile. Something like the Eton wall game was going on in the narrow gangway. I made towards a petite dark girl looking very much alone, but the only people who get to sit next to girls like that are the men who model the airline adverts. I was next to a thick-necked idiot of about twenty-two stone. He sat down with a hat and overcoat on and wouldn’t give either to the steward. He had boxes and bags and a packet of sandwiches. I strapped in and he looked at me in amazement. ‘Floorn before?’ I gave him the side focus and nodded like I was deep in contemplation. The steward helped him strap in, the steward helped him find his brief-case, he helped him understand that although the plane went to Sydney via Colombo he only need go to Rome. The steward showed him how to fit on, and tie up, his life-jacket, how the light switched itself on in water, where to find the whistle and turn on the compressed air. Told him he couldn’t buy a drink until we were airborne. Showed him where to find his maps and told him how high we were. (We were still on the ground.) When we got to the end of the runway we hung around while an Alitalia DC8 came in, then with a screaming great roar, the brakes were off and we rolled, gaining speed, down the wide runway. Past airport buildings and parked aircraft, a couple of jolts as the machine gained buoyancy and airspeed. The cars on the London Road became smaller and the sun glinted dully on the many sheets of water around the Airport. Strange castles, baronial mansions, that appear only when you are in an aeroplane. One by one I remembered them and again promised myself a journey in search of them some day.

About Guildford the stewardess offered us the free alcohol that together with six extra inches of seat space makes the cost of a first-class ticket worth while, if you are on expenses. Gravel Gertie, of course, wanted something odd – ‘A port and lemon.’ The hostess explained they didn’t have such a thing. He decided to ‘Leave it to you, love, I don’t do much travelling.’

Our drinks arrived. He passed me my glass of sherry and insisted upon bumping our glasses together like mating tortoises, and saying, ‘Cheerio, Chin-chin.’

I nodded coolly as the spilt sherry pioneered its sticky route down my ankle.

‘Over the teeth, over the gums, look out stomach, here she comes,’ he chanted, and was such a helpless roistering jelly of merriment at his own wit that only a small fraction of his drink did in fact complete the journey. I wrote ROUNDELAYS into the crossword. ‘I’m going to Rome,’ said Gertie. ‘Have you ever been there?’

I nodded without looking up.

‘I missed the 9.45 plane. That’s the one I should have been on, but I missed it. This one doesn’t always go to Rome, but that 9.45 goes direct to Rome.’

I crossed out ROUNDELAYS and wrote RONDOLETTO. He kept saying ‘I’ll go no more a-roaming,’ and laughing a little high-pitched laugh, his great floppy face crouching behind his pink-tinted rimless spectacles. I was into the competition page of the Statesman when the stewardess offered me a selection of pieces of toast as large as a penny garnished with smoke salmon and caviare. Fatso said, ‘What are we ’aving to eat, luv, spaghetti?’ A thought that drove him wild with hysterical mirth, in fact he repeated the word to me a couple of times and roared with laughter. A toy dinner came along on a trolley; I declined the fat man’s thick sausage sandwiches. I had frozen chicken, frozen pomme parisienne and frozen peas. I began to envy Fatso his sausage sandwiches. By the time we were crossing the suburbs of Paris the champagne appeared. I felt mollified. I crossed out RONDOLETTO and wrote in DITHYRAMBS which made twenty-one down AWE instead of EWE. It was beginning to shape up.

We skimmed our way into the clouds like a nose into beer froth. ‘We are approaching Rome – Fiumicino Airport. Transit time is forty-five minutes. Please do not leave small valuable articles in the aircraft. Passengers may remain aboard but smoking is not permitted during refuelling. Please remain seated after landing. Light refreshments will be available in the airport restaurant. Thank you.’

I accidentally knocked Fatso’s glasses out of his hand on to the floor, one pane suffered a crack but held together. While we apologized together we came in over the eternal city. The old Roman aqueducts were clearly visible, so was Fatso’s wallet, so I lifted it, offered him my seat – ‘Your first view of Rome.’

‘When in Rome …’ he was saying as I took off to the forward toilet, I heard his high-pitched laugh. ‘Occupied.’ Damn. I stepped into the bright chromium galley. No one there. I leaned into the baggage recess. I flipped through Fatso’s wallet. A wad of fivers, some pressed leaves, two blank postcards with views of Marble Arch, a five-shilling book of stamps, some dirty Italian money and a Diner’s Club card in the name of HARRISON B J D and some photos. I had to be very quick. I saw the stewardess walking slowly down the aisle checking passengers’ seat belts, and the lights were up. ‘NO SMOKING, FASTEN SEAT BELTS.’ She was going to give me the rush. I pulled the photos out – three passport pictures of a dark-haired, smooth stockbroker type, full, profile and three-quarter. The photo was different but the man was my pin-up, too – the mysterious Raven. The other three photos were also passport style – full face, profile and three-quarter positions of a dark-haired, round-faced character; deep sunk eyes with bags under horn-rimmed glasses, chin jutting and cleft. On the back of the photos was written ‘5ft 11in; muscular inclined to overweight. No visible scar tissue; hair dark brown, eyes blue’. I looked at the familiar face again. I knew the eyes were blue, even though the photograph was in black and white. I’d seen the face before; most mornings I shaved it. I realized who Fatso was. He was the fat man sitting at the bar in the strip-club when the cigarette girl told me to ‘Go home.’

I stuffed them back, palmed the wallet, said ‘OK’ to the protesting hostess. I got back to my seat as the flaps went down, the plane shuddered like Gordon Pirie running into a roomful of cotton wool. Fatso was back in his own seat; my cardigan had fallen to the floor over my brief-case. I sat down quickly, strapped in. I could see the Railway Junction now and as we levelled off for the approach the G glued me to the seat springs. I could see the south side of the perimeter as we came in, and beyond the bright yellow Shell Aviation bowsers I noticed a twin-engined shoulder wing Grumman S2F-3. It was painted white and the word ‘NAVY’ was written in square black letters aft of the American insignia.

The tyres touched tarmac. I leaped forward to pick up my mohair cardigan. As I did so I flipped Fatso’s wallet well under his seat. Now I saw the clean knife cut along the back of my new brief-case – still unopened. Not one of those long, amateur sorts of cuts, but a small, professional, ‘poultry-cleaning’ one. Just enough to investigate the contents. I leaned back. Fatso offered me a peppermint. ‘Do as the Romans do,’ he went on, eyes smiling through the cracked lens.

Fiumicino Airport, Rome, is one of those straight-sided ‘Contemporary Economy’ affairs. I went into the main entrance; to the left was the restaurant but up the stairs to the right a post office and money exchange. I was killing a minute with the paperbacks when I heard a soft voice say, ‘Hello, Harry.’

Now my name isn’t Harry, but in this business it’s hard to remember whether it ever had been. I turned to face the speaker – my driver from London. He had a hard bony skull, with hair painted across it in Brylcreem. His eyes were black and counter-sunk deep into his face like gun positions. His chin was blue and hardened by wind, rain and monsoon and forty years of shaving hard against the bone. He wore black tie and white shirt and navy blue raincoat with shoulder straps. If he was a crew member he had removed his shoulder badges and taken care to leave his uniform cap elsewhere. If he wasn’t, it was little wonder that he chose to wear the undress uniform of all the world’s airline crews.

His eyes moved in constant watchfulness over my shoulder. He ran the palm of his right hand hard across the side of his head to press down his already flattened hair. ‘Seat nineteen …’

‘Is trouble,’ I completed it in the phraseology of the department. He looked a little sheepish. ‘Now you tell me,’ I said peevishly. ‘He’s already shivved my hand baggage.’

‘As long as there is still a tin inside,’ he said.

‘There’s a tin inside,’ I told him.

As I thanked him I heard the Italian voice on the loudspeaker saying, ‘British Overseas Airways Corporation denunca che departe dela Comet volo BA712 a Beirut, Bahrain, Bombay, Colombo, Singapore, Jakarta, Darwin and Sydney a tutto passagere …’

He rubbed the side of his jaw pensively, and finally said, ‘Be last out at Beirut. Leave that,’ we both eyed the case, ‘for me to take through customs.’ He said good-bye then turned to go, but came back to cheer me up. ‘We’re doing seat nineteen’s hold baggage now,’ he said.

The Colosseum – Rome’s rotten tooth – sank behind us, white, ghostly and sensational. I slept till Athens. Fatso hadn’t re-embarked. I felt tired and out-gambited. I slept again.

I woke for coffee as we crossed the brown coast of Lebanon. Thin streaks of white crests buffered in from the blue Med. I noticed that there were many tall white buildings built since my first visit here in the days of Medway II.

The circuit over the coast-side airport is generally a bumpy passage, for immediately after the airport the ground rises in blunt green mountains. Everything is hot, foreboding and very old.

Polite soldier-like officials in khaki uniforms did a line of backwards Arabic in immaculate penmanship across my passport and stamped it. I had cleared customs and immigration.

I dumped my wardrobe case into a Mercedes taxi – after letting two cabs go by – then gave the driver some Lebanese pounds and told him to wait. He was a villainous-looking Moslem in brown woollen hat, bright red cardigan and tennis shoes. I hurried upstairs. Having coffee near the juke-box was the ‘driver’. He gave me my brief-case, a heavy brown packet, a heavy brown look, a heavy brown coffee. I dealt with each in silence. He gave me the address of my hotel in town.

The Mercedes touched seventy-five as we passed the dense wood of tall umbrella pines along the wide modern road to the town. Further away on the mountain slopes the cedar trees stood, national symbol and steady export for over 5,000 years. ‘Hew me cedar trees out of Lebanon,’ Solomon had commanded and from them built his temple. But my driver didn’t care.

6 (#ulink_d90bfd98-a4ea-5b87-8992-aba256d64532)

[Aquarius (Jan 20–Feb 19) Someone else’s forethought may enable you to surprise a rival.]

Peering between the slats of the wide venetian blind, the yellow and orange stucco buildings conspired to hide the sea. In the warmth of midday I see a black moustachioed villain hitting the horn of a pink Caddie; the cause of his annoyance a child leading a camel with a predilection for acacia trees. Across the road two fat men sit on rusty folding chairs drinking arak and laughing; a foot or so above their heads a coloured litho Nasser is not amused. In economy-sized cafés behind doors artfully contrived to preserve a décor of absolute darkness they are serving economy-sized coffees of similar darkness with exotic pastries of honey-smothered nuts and seeds. Clients – young Turks, Greeks dressed like left bank intellectuals – find their seats by the light of a juke-box inside which Yves Montand and Sarah Vaughan are crowded. Outside in the blinding sunlight, antiquated trams spew out agile targets for the Mercedes taxis. Dark-skinned young men with long black hair parade along the water’s edge in bikinis almost big enough to conceal a comb. Below me in the street two young men on rusty cycles balancing a long tray of unleavened bread between them, are nearly brought down by a frenetic dog which yelps its fear and anger. In the souks men from the desert pass among money-changers – the carpet men and the sellers of saddles for horse, camel and bicycle. In Room 624 bars of sunlight lay heavily across the carpet. The hotel intercom hummed with old tapes of Sinatra, but he was losing a battle with the noise of the air-conditioning. Room 624, which the department had booked for me, came complete with private bath, private refrigerator, scales, magnifying mirrors, softened water, phones by bed, phones by bath. I poured another large cup of black coffee and decided to investigate my baggage. The blue wardrobe bag unzipped to reveal – a light-weight blue worsted suit, a seersucker jacket, a used overall with zip front and more pockets than I knew how to use. In the bag’s side pockets were some new white and plain-coloured cotton shirts, a couple of plain ties, one wool, one silk, a belt, a slim leather and Italian, and a pair of red braces; didn’t miss a trick, that Alice. I was going to like working for WOOC(P). In the brief-case was a heavy tin. I looked at the label. It read ‘WD 310/213. Bomb. Sticky’. The heavy packet that the man in the blue raincoat had given me was an envelope inside which was a waterproof-lined brown bag. It was the sort of thing you would find in the pocket of your seat when looking for matches on an aeroplane. It is also the sort of thing that aircrews, loaders, and engineers from Rangoon to Rio use for transporting their little ‘finds’. Cakes, chicken, ball-point pens, packs of cards, butter – the jetsam of the airlines. Inside this one was a hammerless Smith and Wesson, safety catch built into the grip, six chambers crowded with bullets. I tried to remember the rules about unfamiliar

pistols. In an accompanying box were twenty-five rounds, two spare chambers (greased to hold the shells in tight), and a cutaway holster. It covered little more than the barrel, having a small spring clip for rigidity. I strapped the belt across my shoulder. It fitted very well. I played with this in front of the mirror, making like Wagon Train, then drank the rest of my cold coffee. Orders would come soon enough: orders for a last attempt to grab Raven the biochemist before he disappeared beyond our reach.

The road inland from Beirut winds up into the mountains; gritty little villages hold on tight to the olive trees. The red earth gives way to rock, and far below to the north lies St George’s Bay, where the dragon got his, way back, that was. Up here where the snow hangs around six months of the year the ground is dotted with little Alpine flowers and yellow broom, in some places wild liquorice grows. Once the heights are crossed the road drops suddenly and there is a route across the valley before the crossing of the next range – the Anti Lebanon, behind which lies 500 miles of nothing but sand till Persia. Much nearer than that, though, just along the road in fact, is Syria.

At many places the roadway cuts corners, and a shelf hangs almost over the road. A full grown man can, if he keeps very still, perch between two pieces of rock at one place I know. If while in this position he looks east he can see the road for over a hundred yards; if he looks towards Beirut he can see even farther – about three hundred yards, and what’s more, he can, through night glasses, watch the road crossing the mountain. If he has friends up the road in either direction and a small trans-receiver he can talk to them. Although he shouldn’t do so indiscriminately in case the police radio accidentally monitors the call. Along about 3.30 A.M. a man in this position will have counted the stars, almost fallen off the rock easing his back-ache and be seeing double through the night glasses. The metal of the trans-receiver will be sending pains of cold through hand and ear, and he will have begun to compile a list of friends prepared to help him in the matter of finding some other type of employment, and I won’t blame him. It was 3.32 A.M. when I saw the headlights coming down the mountain road. Through the night glasses I could see it was wide and rolled like an American car. I switched in my set and saw the movement up the road as the radio man gave it to Dalby. ‘One motor, over a thousand yards. No traffic. Out.’ Dalby grunted.

I read off the ranges army style until finally the large grey Pontiac slid under me, headlights probing the soft sides of the road. The beams were way above Dalby’s head. I could imagine him, crouching there, perfectly still. In these sorts of situation Dalby sat back and let his subconscious take over; he didn’t have to think – he was a natural hooligan. The car had slowed as Dalby knew it must, and as it neared him he stood up and posed, like the statue of the discus thrower, aimed – then lobbed his parcel of trouble. It was a sticky bomb about as big as two cans of soup end to end; on impact its very small explosive charge spread a sort of napalm through tank visors. Burnt cars and contents don’t worry policemen the way blown-up shot-up ones do. The charge exploded. Dalby dropped almost flat, some flaming pieces of horror narrowly missed him, but mostly they hit radiator and tyre. The car hadn’t slackened speed, and now Dalby was on his feet and running behind it. We’d parked the old car from Beirut obliquely across the path; the man driving our target must have been dead from the first impact, for he made no attempt to collide side to side in sheer, but just ploughed into the old Simca carrying it about eight feet. By now Dalby was alongside. He had the door open and I heard pistol shots as he groped into the rear seat. My trans-receiver made a click as someone switched in and said in a panicky voice, which forgot procedure, ‘What you doing, what you doing?’ For a fraction of a second I thought he was asking Dalby; then I saw it.