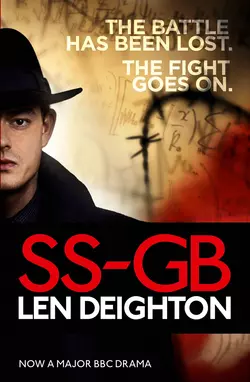

SS-GB

Len Deighton

In February 1941 British Command surrendered to the Nazis. Churchill has been executed, the King is in the Tower and the SS are in Whitehall…For nine months Britain has been occupied - a blitzed, depressed and dingy country. However, it’s ‘business as usual’ at Scotland Yard run by the SS when Detective Inspector Archer is assigned to a routine murder case. Life must go on.But when SS Standartenfuhrer Huth arrives from Berlin with orders from the great Himmler himself to supervise the investigation, the resourceful Archer finds himself caught up in a high level, all action, espionage battle.This is a spy story quite different from any other. Only Deighton, with his flair for historical research and his narrative genius, could have written it.

LEN DEIGHTON

SS-GB

Copyright (#u34757546-68c2-5f77-aa05-3a0133075a98)

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

A paperback edition 2009

FIRST EDITION

First published in Great Britain by

Jonathan Cape Ltd 1978

Cover design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2017 Cover photograph © Sid Gentle Films Ltd 2017

Copyright © Len Deighton 1978

Introduction copyright © Pluriform Publishing Company BV 2009

The verse from ‘The White Cliffs of Dover’ is reproduced by permission of EMI Publishers Ltd 138–140 Charing Cross Road, London WC2H 0LD. © 1941 by Shapiro Bernstein & Co., Inc., subpublished by B. Feldman & Co. Ltd

Len Deighton asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

Ebook Edition © 1978 ISBN: 9780007347742

Version: 2017-05-22

Table of Contents

Cover (#ue8d2bb1a-9343-5e4c-86ec-829253ebe6f4)

Title Page (#uf37fa5d7-3c57-5423-bd26-4dfa655fbbd0)

Copyright (#u6d8a927a-1957-5cc1-8634-efbefaad8913)

Introduction (#uc6040368-d30b-52d2-b632-01c7b054aa57)

Chapter One (#ubf227d7b-4796-583f-94d8-de4c3b4d4161)

Chapter Two (#u603026f0-922c-597c-ae16-515fc7817471)

Chapter Three (#u216480ae-9f56-5ffb-a46a-7ce909d45bbc)

Chapter Four (#u37ff6e25-3fb5-56c2-8250-0e4d60a1c37e)

Chapter Five (#ue74bd6d2-3137-5b68-9e98-c782156f5b77)

Chapter Six (#uf16a53a7-4fc1-5f94-91da-379d1659b144)

Chapter Seven (#ud724cfac-3f67-50de-bc7c-412e3dbbec7e)

Chapter Eight (#u0ce5df5b-53b9-54b3-b7c3-c02f9bfe2276)

Chapter Nine (#u6d468319-aad9-5d8e-b8c4-ff07675dec84)

Chapter Ten (#u9acdf749-b32b-5f98-b740-d2cdd6ffda7d)

Chapter Eleven (#u908b7b8e-fd8c-5cb1-b779-00456ae27fcc)

Chapter Twelve (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fourteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Sixteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seventeen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eighteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nineteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-one (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-two (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-three (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-four (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-five (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-six (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-one (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-two (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-three (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-four (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-five (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-six (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Forty (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

By Len Deighton (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Introduction (#u34757546-68c2-5f77-aa05-3a0133075a98)

‘My book, Inside the Third Reich, never reached the top of the New York best seller list,’ Albert Speer told me. ‘It was Everything You Always Wanted to Know About Sex but were afraid to ask that always remained at number one.’

I am still not sure if he was joking. Hitler’s onetime Minister of Armaments had a sharp sense of humour, especially about the men with whom he had been in Spandau prison; he always referred to Field Marshal Milch as ‘Milk’. And when writers get together sales talk is not unusual.

But Albert Speer was not the catalyst for SS-GB. It began over a late-night drink with Ray Hawkey the writer and designer, and Tony Colwell my editor at Jonathan Cape. ‘No one knows what might have happened had we lost the Battle of Britain,’ said Tony with a sigh as we finished sorting through photos to illustrate my book, Fighter: The True Story of the Battle of Britain.

‘I wouldn’t go as far as that,’ I told him. ‘A great deal of the planning for the German occupation has been found and published.’

I had read some of that material and, after this conversation, I sought out the official German publications and began wondering if Britain under German rule would make a book. It would have to be what was then called an ‘alternative world’ book and that was outside all my writing experience. On the other hand, research for Fighter and Funeral in Berlin and particularly Bomber, had brought me into contact with many Germans, mostly men who had fought in the war.

I work very slowly so I don’t embark on a story until I am confident that I will be able to get the material for it and live with it for many months, perhaps years. The plot problems seemed insurmountable. Would I create a hero in the German occupation army? I wouldn’t want a Nazi as a hero. If I told the story through the eyes of a British civilian how would such a person have enough information to make the plot work? A notable member of the resistance would qualify as a hero but such heroes would all be dead, or fugitives.

This story had to be told from the centre of power. The police would be the people who connected the conquerors with the conquered but that sort of compromise role was not attractive to me. I went round and round on this until I thought of a Scotland Yard detective as hero. A man who solved crimes and hunted only real criminals could have contacts at the top and yet still be acceptable as a central character. I would frame it like a conventional murder mystery, with corpse at the start and solution at the end.

I like big charts and diagrams. They serve as a guide and reminder while a book is being written. Using the German data I drew a chain of command showing the connections between the civilians and the puppet government, black-marketeers and quislings and the occupying power with its security forces and bitterly competitive army and Waffen SS elements. My old friend, and fellow writer, Ted Allbeury had spent the immediate post-war period in occupied Germany as what the locals called ‘the head of the British Gestapo’. Ted’s experience was very valuable indeed and I used his experience and anecdotes to the full.

For the London scenes, I used only places that I had known in the war, so in that respect there is an autobiographical element in the story. I remembered London in wartime: the dimly lit streets, gas lights that hissed and spluttered, tin baths in front of the fire, rationing that made food a constant subject of thought and conversation, and bombed homes that spewed their intimate household contents into the streets.

The Scotland Yard building had to be the stage upon which my story was played but the police were no longer using it. It had become an office building for members of parliament and was strictly guarded. The Metropolitan Police were very cooperative about letting me into their new building and they let me use their fascinating library and their archives too without restrictions of any kind. I spent many days studying wartime crimes and looking at pictures of Scotland Yard detectives in the natty suits that were mandatory at that time. But the obstacle remained, the police had no authority over the building they had vacated.

By a wonderful piece of luck I found an elderly ex-policeman who knew the building from cellar to attic. I recorded hours of his descriptions but I still could not get into it until a friend named Freddy Warren devised a method by which I could explore every nook and cranny of the historic Scotland Yard building. Freddy’s authority as an official of the Whip’s office was to allot the offices to the politicians. He took me on a guided tour. With him I went everywhere; opening doors, interrupting conferences, awakening sleepers and declining liquid refreshment. No one was going to risk upsetting Freddy. I remain indebted to him and I hope that this record of the Scotland Yard building, as once it was, justifies the trouble he took on my behalf.

When writing the main text begins I have found it beneficial to step away from phones and friends and any social commitments. Together with my wife Ysabele and two small children I climbed into an old Volvo with its trunk crammed with research material. We went to Tuscany. My friend Al Alvarez the writer and broadcaster lent us his wonderful mountainside house near Barga. It was winter and, no matter about the pictures in the brochures, winter in northern Italy is cold and wet. I searched far and wide for an electric typewriter and failed to find one. All I could find was a tiny lightweight portable Olivetti Lettera 22. Yes I know the Lettera 22 is an icon of the nineteen fifties and is found in design museums, but after the soft touch joys of an electric machine, pounding the mechanical keyboard took a lot of getting used to. My fingers swelled up like salsiccia Toscana. But rural Italy worked its magic. Our elderly ‘next door’ neighbours adopted us. Signora Ida and her husband Silvio lavished our children with love, made pizzas for us in their outdoor oven and showed us the secret of making ravioli and the secret of happiness on the slim budget that a few olive trees provide. We will never forget those two wonderful people. They made my time in Tuscany writing SS-GB one of the happiest times of my happy life.

Len Deighton, 2009

‘In England they’re filled with curiosity and keep asking, “Why doesn’t he come?” Be calm. Be calm. He’s coming! He’s coming!’

Adolf Hitler. 4 September 1940, at a rally of nurses and social workers in Berlin.

Oberste Befehlshaber

Berlin, den 18.2.41

Der Oberste Befehlshaber der Wehrmacht

10 Ausfertigungen Ausfertigung

Instrument of Surrender – English Text. Of all British armed forces in United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland including all islands.

1 The British Command agrees to the surrender of all British armed forces in the United Kingdom and Northern Ireland including all islands and including military elements overseas. This also applies to units of the Royal Navy in all parts of the world, at port and on the high seas.

2 All hostilities on land, sea and in the air by British forces are to cease at 0800 hrs Greenwich Mean Time on 19 February 1941.

3 The British Command to carry out at once, without argument or comment, all further orders that will be issued by the German Command on any subject.

4 Disobedience of orders, or failure to comply with them, will be regarded as a breach of these surrender terms and will be dealt with by the German Command in accordance with the laws and usages of war.

5 This instrument of surrender is independent of, without prejudice to, and will be superseded by any general instrument of surrender imposed by or on behalf of the German Command and applicable to the United Kingdom and the Allied nations of the Commonwealth.

6 This instrument of surrender is written in German and English. The German version is the authentic text.

7 The decision of the German Command will be final if any doubt or dispute arises as to the meaning or interpretation of the surrender terms.

Chapter One (#u34757546-68c2-5f77-aa05-3a0133075a98)

‘Himmler’s got the king locked up in the Tower of London,’ said Harry Woods. ‘But now the German Generals say the army should guard him.’

The other man busied himself with the papers on his desk and made no comment. He thumped the rubber stamp into the pad and then on to the docket, ‘Scotland Yard. 14 Nov. 1941’. It was incredible that the war had started only two years ago. Now it was over; the fighting finished, the cause lost. There was so much paperwork that two shoe boxes were being used for the overflow; Dolcis shoes, size six, patent leather pumps, high heels, narrow fitting. Detective Superintendent Douglas Archer knew only one woman who would buy such shoes: his secretary.

‘Well, that’s what people are saying,’ added Harry Woods, the elderly Sergeant who was the other half of the ‘murder team’.

Douglas Archer initialled the docket and tossed it into the tray. Then he looked across the room and nodded. It was a miserable office, its green and cream painted walls darkened by age and the small windows heavily leaded and smeared by sooty rain, so that the electric light had to be on all day.

‘Never do it on your own doorstep,’ advised Harry now that it was too late for advice. Anyone other than Harry, anyone less bold, less loquacious, less well-meaning would have stopped at that. But Harry disregarded the fixed smile on his senior partner’s face. ‘Do it with that blonde, upstairs in Registry. Or that big-titted German bird in Waffen-SS liaison – she puts it about they say – but your own secretary…’ Harry Woods pulled a face.

‘You spend too much time listening to what people say,’ said Douglas Archer calmly. ‘That’s your trouble, Harry.’

Harry Woods met the disapproving stare without faltering. ‘A copper can never spend too much time listening to what other people say, Super. And if you faced reality, you’d know. You may be a bloody wonderful detective, but you’re a shocking bad judge of character – and that’s your trouble.’

There weren’t many Detective Sergeants who would dare speak to Douglas Archer like that but these two men had known each other ever since 1920, when Harry Woods was a handsome young Police Constable with a Military Medal ribbon on his chest, and a beat littered with the broken hearts of pretty young housemaids and the hot meat pies of doting cooks. While Douglas Archer was a nine-year-old child proud to be seen talking to him.

When Douglas Archer became a green young Sub-Divisional Inspector, straight from the Hendon Police College, with no more experience of police work than comes from dodging the Proctors in the back streets of Oxford, it was Harry Woods who had befriended him. And that was at a time when such privileged graduates were given a hard time by police rank and file.

Harry knew everything a policeman had to know and more. He knew when each night-watchman brewed tea, and was never far from a warm boiler house when it rained. Harry Woods knew which large piles of rubbish would have money under them, never taking more than a third of it, lest the shopkeeper found some other way to pay the street-cleaners for their extra work. But that was a long time ago, before the generosity of the publicans and barmen of London’s West End had provided Harry with his ruddy face and expanded his waistline. And before Douglas Archer’s persistence got him into CID and then to Scotland Yard’s Murder Squad.

‘C Division have got a juicy one,’ said Harry Woods. ‘Everyone else is busy. Shall I get the murder bag ready?’

Douglas knew that his Sergeant expected him to respond in surprise, and he raised an eyebrow. ‘How the devil do you know about it?’

‘A flat in Shepherd Market, crammed with whisky, coffee, tea and so on, and Luftwaffe petrol coupons lying around on the table. The victim is a well-dressed man, probably a black-marketeer.’

‘You think so?’

Harry smiled. ‘Remember that black-market gang who killed the warehouse manager in Fulham…they were forging Luftwaffe petrol coupons. This could be the same mob.’

‘Harry. Are you going to tell me where all this information comes from, or are you going to solve the crime without getting out of your seat?’

‘The Station Sergeant at Savile Row is an old drinking pal. He just phoned me. A neighbour found the body and told the police.’

‘There’s no hurry,’ said Douglas Archer. ‘We’ll move slowly.’

Harry bit his lip. In his opinion Detective Superintendent Douglas Archer never did otherwise. Harry Woods was a policeman of the old school, scornful of paperwork, filing systems and microscopes. He liked to be talking, drinking, interrogating and making arrests.

Douglas Archer was a tall, thin, thirty-year-old. He was one of a new generation of detectives, who’d rejected the black jacket, pin-stripe trousers, roll-brim hat and stiff collar that was almost a uniform for the Murder Squad. Douglas favoured dark shirts and the sort of wide-brimmed hat he’d seen on George Raft in a Hollywood gangster film. In keeping with this, he’d taken to smoking small black cheroots as often as his tobacco ration permitted. He tried to light this one for the third time; the tobacco was of poor quality and it did not burn well. He looked for more matches and Harry threw a box across to him.

Douglas was a Londoner – with the quick wit and sophisticated self-interest for which Londoners are renowned – but like many who grow up in a fatherless household, he was introspective and remote. The soft voice and Oxford accent would have better suited some more cloistered part of the legal profession but he’d never regretted becoming a policeman. It was largely due to Harry, he realized that now. For the lonely little rich boy, in the big house on the square, Harry Woods, without knowing it, became a surrogate father.

‘And suppose the Luftwaffe petrol coupons are not forgeries; suppose they are real,’ said Douglas. ‘Then you can bet German personnel are involved, and the case will end up with the Feldgericht der Luftwaffe, Lincoln’s Inn. Waste of time our getting involved.’

‘This is murder,’ said Harry. ‘A few petrol coupons can’t change that.’

‘Don’t try to re-write the laws, Harry, there’s enough work enforcing the ones we’ve got. Any crimes involving Luftwaffe personnel, in even the smallest way, are tried by Luftwaffe courts.’

‘Not if we got over there right away,’ said Harry, running his hand back over hair that refused to be smoothed down. ‘Not if we wrung a confession out of one of them, sent copies to Geheime Feldpolizei and Kommandantur, and gave them a conviction on a plate. Oherwise these German buggers just quash these cases for lack of evidence, or post the guilty ones off to some soft job in another country.’

For Harry the fighting would never end. His generation, who’d fought and won in the filth of Flanders, would never come to terms with defeat. But Douglas Archer had not been a soldier. As long as the Germans let him get on with the job of catching murderers, he’d do his work as he’d always done it. He wished he could get Harry to see it his way.

‘I’d appreciate it, Harry, if you’d not allow your personal opinions to intrude into the preferred terminology.’ Douglas tapped the SIPO Digest. ‘And I’m far from convinced that they are soft on German personnel. Five executions last month; one of them a Panzer Division Major, with Knight’s Cross, who did nothing worse than arrive an hour late to check a military vehicle compound.’ He tossed the information sheets across to his partner’s desk.

‘You read all that stuff, don’t you?’

‘And if you had more sense, Harry, you’d read it too. Then you’d know that General Kellerman now has his CID briefings on Tuesday morning at eleven o’clock, which is just ten minutes from now.’

‘Because the old bastard drinks too much at lunch-time. By the time he reels back from the SS Officers’ Club in the afternoon he can’t remember a word of English except, “tomorrow, tomorrow!”’

Harry Woods noted with satisfaction the way that Douglas Archer glanced round the empty chairs and desks, just in case anyone had overheard this pronouncement. ‘Whatever the truth of that may be,’ said Douglas cautiously, ‘the fact remains that he’ll want his briefing. And solving a murder that we’ve not yet been invited to investigate will not be thought sufficient excuse for my not being upstairs on time.’ Douglas got to his feet and collected together the documents that the General might want to see.

‘I’d tell him to go to hell,’ said Harry. ‘I’d tell him the job comes first.’

Douglas Archer nipped out his cheroot carefully, so as to preserve the unsmoked part of it, then put it into the top drawer of his desk, together with a magnifying glass, tickets for a police concert he’d not attended, and a broken fountain pen. ‘Kellerman’s not so bad,’ said Douglas. ‘He’s kept the Metropolitan Force more or less intact. Have you forgotten all the talk of putting German Assistant Commissioners upstairs? Kellerman opposed that.’

‘Too much competition,’ muttered Harry, ‘and Kellerman doesn’t like competition.’

Douglas put his report, and the rest of the papers, into his briefcase and strapped it up. ‘In the unlikely event that West End Central ask for us, have the murder bag ready and order a car. Tell them to keep the photographer there until I tell him to go and to keep the Divisional Surgeon there, as well as the pathologist.’

‘The doctor won’t like that,’ said Harry.

‘Thanks for telling me that, Harry. Send the doctor a packet of wait-about tablets with my compliments, and remind him you are phoning from Whitehall 1212, Headquarters of Kriminalpolizei, Ordnungspolizei, Sicherheitsdienst and Gestapo. Any complaints about waiting can be sent here in writing.’

‘Keep your shirt on,’ said Harry defensively.

The phone rang; the calm impersonal voice of General Kellerman’s personal assistant said, ‘Superintendent Archer? The General presents his compliments and asks if this would be a convenient time for you to give him the CID briefing.’

‘Immediately, Major,’ said Douglas, and replaced the phone.

‘Jawohl, Herr Major. Kiss your arse, Herr Major,’ said Harry.

‘Oh for God’s sake, Harry. I have to deal with these people at first hand; you don’t.’ ‘I still call it arse-licking.’

‘And how much arse-licking do you think it needed to get your brother exempted from that deportation order!’ Douglas had been determined never to tell Harry about that, and now he was angry with himself.

‘Because of the medical report from his doctor,’ said Harry but even as he was saying it he realized that most of the technicians sent to German factories probably got something like that from a sympathetic physician.

‘That helped,’ said Douglas lamely.

‘I never realized, Doug,’ said Harry but by that time Douglas was hurrying up to the first floor. The Germans were sticklers for punctuality.

Chapter Two (#u34757546-68c2-5f77-aa05-3a0133075a98)

General – or, more accurately in SS parlance, Gruppen-führer – Fritz Kellerman was a genial-looking man in his late fifties. He was of medium height but his enthusiasm for good food and drink provided a rubicund complexion and a slight plumpness which, together with his habit of standing with both hands in his pockets, could deceive the casual onlooker into thinking Kellerman was short and fat, and so he was often described. His staff called him ‘Vater’ but if his manner was fatherly it was not benign enough to earn him the more common nickname of ‘Vati’ (Daddy). His thick thatch of white hair had beguiled more than one young officer into accepting his invitation for an early morning canter through the park. But few of them went for the second time. And only the greenest of his men would agree to a friendly game of chess, for Kellerman had once been the junior chess champion of Bavaria. ‘Luck seems to be with me today,’ he’d tell them as they became trapped into a humiliating defeat.

Before the German victory, Douglas had seldom visited this office on the first floor. It was the turret room used hitherto only by the Commissioner. But now he was often here talking to Kellerman, whose police powers extended over the whole occupied country. And Douglas – together with certain other officers – had been granted the special privilege of entering the Commissioner’s room by the private door, instead of going through the clerk’s office. Before the Germans came, this was something permitted only to Assistant Commissioners. General Kellerman said it was part of das Führerprinzip; Harry Woods said it was bullshit.

The Commissioner’s office was more or less unchanged from the old days. The massive mahogany desk was placed in the corner. The chair behind it stood in the tiny circular turret that provided light from all sides, and a wonderful view of the river. There was a big marble mantelpiece and on it an ornate clock that struck the hour and half-hour. A fire blazed in the bow-fronted grate between polished brass fire-irons and a scuttle of coal. The only apparent change was the shoal of fish that swam across the far wall, in glass-fronted cases, stuffed, and labelled with Fritz Kellerman’s name, and a place and date, lettered in gold.

There were two men in army uniform there when Douglas entered the room. He hesitated. ‘Come in, Superintendent. Come in!’ called Kellerman.

The two strangers looked at Douglas and then exchanged affirmative nods. This Englishman was exactly right for them. Not only was he reputed to be one of the finest detectives in the Murder Squad but he was young and athletic looking, with the sort of pale bony face that Germans thought was aristocratic. He was ‘Germanic’, a perfect example of ‘the new European’. And he even spoke excellent German.

One of the men picked up a notebook from Kellerman’s desk. ‘Just one more, General Kellerman,’ he said. The other man seemed to produce a Leica out of nowhere and knelt down to look through its viewfinder. ‘You and the Superintendent, looking together at some notes or a map…you know the sort of thing.’

On the cuffs of their field-grey uniforms the men wore ‘Propaganda-Kompanie’ armbands.

‘We’d better do as they say, Superintendent,’ said Kellerman. ‘These fellows are from Signal magazine. They’ve come all the way from Berlin just to talk to us.’

Awkwardly Douglas went round to the far side of the desk. He posed self-consciously, prodding at a copy of the Angler’s Times. Douglas felt foolish but Kellerman took it all in his stride.

‘Superintendent Archer,’ said the PK journalist in heavily accented English, ‘is it true that, here at Scotland Yard, the men call General Kellerman “Father”?’

Douglas hesitated, pretending to be holding still for the photo in order to gain time. ‘Can’t you see how your question embarrasses the Superintendent?’ said Kellerman. ‘And speak German, the Superintendent speaks the language as well as I do.’

‘It’s true then?’ said the journalist, pressing for an answer from Douglas. The camera shutter clicked. The photographer checked the settings on his camera and then took two more pictures in rapid succession.

‘Of course it’s true,’ said Kellerman. ‘You think I’m a liar? Or do you think I’m the sort of police chief who doesn’t know what goes on in my own headquarters?’

The journalist stiffened and the photographer lowered his camera.

‘It’s quite true,’ said Douglas.

‘And now, gentlemen, I must get some work done,’ said Kellerman. He shooed them out, like an old lady finding hens in her bedroom. ‘Sorry about that,’ Kellerman explained to Douglas after they’d gone. ‘They said they would need only five minutes, but they hang on and hang on. It’s all part of their job to exploit opportunities, I suppose.’ He went back to his desk and sat down. ‘Tell me what’s been happening, my boy.’

Douglas read his report, with asides and explanations where needed. Kellerman’s prime concern was to justify money spent, and Douglas always wrote his reports so that they summarized the resources of the department and showed the cost in Occupation Marks.

When the formalities were over, Kellerman opened the humidor. With black-market cigarettes at five Occupation Marks each, one of Kellerman’s Monte Cristo No 2s had become a considerable accolade. Kellerman selected two cigars with great care. Like Douglas, he preferred the flavour of the ones with green or yellow spots on the outer leaf. He went through a ceremony of cutting them and removing loose strands of tobacco. As usual Kellerman wore one of his smooth tweed suits, complete with waistcoat and gold chain for his pocket watch. Typically he had not worn his SS uniform even for this visit by the photographer. And Kellerman, like so many of the senior SS men of his generation, preferred army rank titles to the cumbersome SS nomenclature.

‘Still no word of your wife?’ asked Kellerman. He came round the desk and gave Douglas the cigar.

‘I think we have to assume that she was killed,’ said Douglas. ‘She often went to our neighbour’s house during the air attacks, and the street fighting completely demolished it.’

‘Don’t give up hope,’ said Kellerman. Was that a reference to his affair with the secretary, Douglas wondered. ‘Your son is well?’

‘He was in the shelter that day. Yes, he’s thriving.’

Kellerman leaned over to light the cigar. Douglas was not yet used to the way that the German officers put cologne on their faces after shaving and the perfume surprised him. He inhaled; the cigar lit. Douglas would have preferred to take the cigar away with him but the General always lit them. Douglas thought perhaps it was a way of preventing the recipient selling it instead of smoking it. Or was it simply that Kellerman believed that, in England, no gentleman could offer a colleague a chance to put an unsmoked cigar in his pocket.

‘And no other problems, Superintendent?’ Kellerman passed behind Douglas, and touched the seated man’s shoulder lightly, as if in reassurance. Douglas wondered if his general knew that his internal mail had that morning included a letter from his secretary, saying she was pregnant and demanding twenty thousand O-Marks. The pound sterling, she pointed out, in case Douglas didn’t know, was not the sort of currency abortionists accepted. Douglas was permitted a proportion of his wages in O-Marks. So far Douglas had not discovered how the letter got to him. Had she sent it to one of her girlfriends in Registry, or actually come into the building herself?

‘No problems that I need bother the General with,’ said Douglas.

Kellerman smiled. Douglas’s anxiety had led him to address the general in that curious third-person form that some of the more obsequious Germans used.

‘You knew this room in the old days?’ said Kellerman.

Before the war it had been the Commissioner’s procedure to leave the door wide open when the room was unoccupied, so that messengers could pass in and out. Soon after being assigned to Scotland Yard, Douglas had found an excuse for coming into the empty room and studying it with the kind of awe that comes from a schoolboy diet of detective fiction. ‘I seldom came here when it was the Commissioner’s room.’

‘These are difficult times,’ said Kellerman, as if apologizing for the way in which Douglas’s visits were now more frequent. Kellerman leaned forward to tap a centimetre of ash into a white china model of Tower Bridge that some enterprising manufacturer had redesigned to incorporate swastika flags and ‘Waffenstillstand. London. 1940’ in red and black Gothic lettering. ‘Until now,’ said Kellerman, choosing his words with care, ‘the police force has not been asked to do any political task.’

‘We have always been completely apolitical.’

‘Now that’s not quite true,’ said Kellerman gently. ‘In Germany we call a spade a spade, and the political police are called political police. Here you call your political police the Special Branch, because you English are not so direct in these matters.’

‘Yes, sir.’

‘But there will come a time when I can no longer resist the pressure from Berlin to bring us into line with the German police system.’

‘We English don’t take quickly to new ideas, you know, sir.’

‘Don’t play games with me, Superintendent,’ said Kellerman without changing the affable tone of voice or the smile. ‘You know what I’m talking about.’

‘I’m not sure I do, sir.’

‘Neither of us wants political advisers in this building, Superintendent. Inevitably the outcome would be that your police force is used against British Resistance groups, uncaptured soldiers, political fugitives, Jews, gypsies and other undesirable elements.’ Kellerman said it in a way that conveyed the idea that he didn’t consider these elements nearly so undesirable as his superiors in Berlin thought them.

‘It would split the police service right down the middle,’ said Douglas.

Kellerman didn’t answer. He reached for a teleprinter message on his desk and read it, as if to remind himself of the contents. ‘A senior officer of the Sicherheitsdienst is on his way here now,’ said Kellerman. ‘I’m assigning you to work with him.’

‘His duties will be political?’ asked Douglas. The SD was the SS intelligence service. Douglas did not welcome this sinister development.

‘I don’t know why he’s coming,’ said Kellerman cheerfully. ‘He is on the personal staff of the Reichsführer-SS and will remain directly responsible to Berlin for whatever he has to do.’ Kellerman inhaled on his cigar and then let the smoke drift from his nostrils. He let his Superintendent dwell upon the facts and realize that the new man presented a danger to the status quo for both of them. ‘Standartenführer Huth,’ said Kellerman finally, ‘that’s this new chap’s name.’ His use of the SS rank was enough to emphasize that Huth was an outsider. Kellerman raised his hand. ‘Under the direct orders of Berlin, so that gives him a special…’ he hesitated and then let the hand fall, ‘…influence.’

‘I understand, sir,’ said Douglas.

‘Then perhaps, my dear chap, you’d do everything you can to prevent the indiscretions – more particularly the verbal indiscretions – of your mentor downstairs from embarrassing us all.’

‘Detective Sergeant Woods?’

‘Ah, what a quick mind you have, Superintendent,’ said Kellerman.

Chapter Three (#u34757546-68c2-5f77-aa05-3a0133075a98)

Some said there had not been even one clear week of sunshine since the cease-fire. It was easy to believe. Today the air was damp, and the colourless sun only just visible through the grey clouds, like an empty plate on a dirty tablecloth.

And yet even a born and bred Londoner, such as Douglas Archer, could walk down Curzon Street, and with eyes half-closed, see little or no change from the previous year. The Soldatenkino sign outside the Curzon cinema was small and discreet, and only if you tried to enter the Mirabelle restaurant did a top-hatted doorman whisper that it was now used exclusively by Staff Officers from Air Fleet 8 Headquarters, across the road in the old Ministry of Education offices. And if your eyes remained half-closed you missed the signs that said ‘Jewish Undertaking’ and effectively kept all but the boldest customers out. And in September of that year 1941, Douglas Archer, in common with most of his compatriots, was keeping his eyes half-closed.

The scene of the murder to which, as Detective Sergeant Harry Woods had predicted, they were called, was Shepherd Market. This little maze of narrow streets and alleys housed a mixture of working-class Londoners, Italian shopkeepers and wealthy visitors, who found in these tortuous ways, and creaking old buildings, some measure of the London they’d read of in Dickens, while being conveniently close to the smart shops and restaurants.

The house was typical of the neighbourhood. There were uniformed police there already, arguing with two reporters. The ground floor was a poky antique shop not much wider than a man could stretch both arms. Above it were rooms of doll’s-house dimensions, with a twisting staircase so narrow that it provided an ever-present risk of sweeping from its walls the framed coaching prints that decorated them. Only with difficulty did Harry get the heavy murder bag to the top floor where the body was.

The police doctor was there, seated on a chintz-covered couch, a British army overcoat buttoned up tight to the neck, and hands in his pockets. He was a young man, in his middle twenties, but already Douglas saw in his eyes that terrible resignation with which so many British seemed to have met final defeat.

On the floor in front of him there was the dead man. He was about thirty-five years old, a pale-faced man with a balding head. Passing him in the street one might have guessed him to be a rather successful academic – the sort of absent-minded professor portrayed in comedy films.

As well as blood, there was a large smudge of brown powder spilled on his waistcoat. Douglas touched it with a fingertip but even before he raised it to his nose, he recognized the heavy aroma of snuff. There were traces of it under the dead man’s fingernails. Snuff was growing more popular as the price of cigarettes went up, and it was still unrationed.

Douglas found the snuff tin in a waistcoat pocket. The force of the bullets had knocked the lid off. There was a half-smoked cigar there too, the band still on it, a Romeo y Julieta worth a small fortune nowadays; no wonder he’d preserved the unsmoked half of it.

Douglas looked at the fine quality cloth and hand stitching of the dead man’s suit. For such expensive, made to measure garments they fitted very loosely, as if the man, suddenly committed to a rigorous diet, had lost many pounds of weight. Sudden weight loss was also suggested by the drawn and wrinkled face. Douglas fingered the bald patches on the man’s head.

‘Alopecia areata,’ said the doctor. ‘It’s common enough.’

Douglas looked into the mouth. The dead man had had enough money to pay for good dental care. Gold shone in his mouth but there was blood there too.

‘There’s blood in his mouth.’

‘Probably hit his face as he fell.’

Douglas didn’t think so but he didn’t argue. He noted the tiny ulcers on the man’s face and blood spots under the skin. He pushed back the shirt sleeve far enough to see the red inflamed arm.

‘Where do you find such sunshine at this time of the year?’ the doctor said.

Douglas didn’t answer. He drew a small sketch of the way that the body had fallen backwards into the tiny bedroom, and guessed that he’d been in the doorway when the bullets hit him. He touched the blood on the body to see if it was tacky, and then placed a palm on the chest. He could feel no warmth at all. His experience told him that this man had been dead for six hours or more. The doctor watched Douglas but made no comment. Douglas got to his feet and looked round the room. It was a tiny place, over-decorated with fancy wallpapers, Picasso reproductions and table lights made from Chianti bottles.

There was a walnut escritoire, with its front open as if it might have been rifled. An old-fashioned brass lamp had been adjusted to bring the light close upon the green leather writing top but its bulb had been taken out and left in one of the pigeon-holes, together with some cheap writing paper and envelopes.

There were no books, no photos and nothing personal of any kind. It was like some very superior sort of hotel room. In the tiny open fireplace there was a basket of logs. The grate was overflowing with ashes of paper.

‘Pathologist here yet?’ Douglas asked. He fitted the light bulb into the brass lamp. Then he switched it on for long enough to see that the bulb was still in working order and switched it off again. He went to the fireplace and put his hand into the ash. It was not warm but there was no surviving scrap of paper to reveal what had been burned there. It was a long job to burn so much paper. Douglas used his handkerchief to wipe his hands.

‘Not yet,’ said the doctor in a dull voice. Douglas guessed that he resented being ordered to wait.

‘What do you make of it, doc?’

‘You get any spare cigarettes, working with the SIPO?’

Douglas produced the gold cigarette case that was his one and only precious possession. The doctor took the cigarette and nodded his thanks while examining it carefully. Its paper was marked with the double red bands that identified Wehrmacht rations. The doctor put it in his mouth, brought a lighter from his pocket and lit it, all without changing his expression or his position, sprawled on the couch with legs extended.

A uniformed Police Sergeant had watched all this while waiting on the tiny landing outside the door. Now he put his head into the room and said, ‘Pardon me, sir. A message from the pathologist. He won’t be here until this afternoon.’

Harry Woods was unpacking the murder bag. Douglas could not resist glancing at him. Harry nodded. Now he realized that to keep the Police Surgeon here was a good idea. The pathologists were always late these days. ‘So what do you make of it, doctor?’ said Douglas.

They both looked down at the body. Douglas touched the dead man’s shoes; the feet were always the last to stiffen.

‘The photographers have finished until the pathologist comes,’ said Harry. Douglas unbuttoned the dead man’s shirt to reveal huge black bruises surrounding two holes upon which there was a crust of dried blood.

‘What do I make of it?’ said the doctor. ‘Gunshot wound in chest caused death. First bullet into the heart, second one into the top of the lung. Death more or less instantaneous. Can I go now?’

‘I won’t keep you longer than absolutely necessary,’ said Douglas without any note of apology in his voice. From his position crouched down with the body, he looked back to where the killer must have been. At the wall, far under the chair he saw a glint of metal. Douglas went over and reached for it. It was a small construction of alloy, with a leather rim. He put it into his waistcoat pocket. ‘So it was the first bullet that entered the heart, doctor, not the second one?’

The doctor still had not moved from his fixed posture on the couch but now he twisted his feet until his toes touched together. ‘There would have been more frothy blood if a bullet had hit the lung first while the heart was pumping.’

‘Really,’ said Douglas.

‘He might have been falling by the time the second shot came. That would account for it going wide.’

‘I see.’

‘I saw enough gunshot wounds last year to become a minor expert,’ said the doctor without smiling. ‘Nine millimetre pistol. That’s the sort of bullets you’ll find when you dig into the plaster behind that bloody awful Regency stripe wallpaper. Someone who knew him did it. I’d look for a lefthanded ex-soldier who came here often and had his own key to get in.’

‘Good work, doctor.’ Harry Woods looked up from where he was going through the dead man’s pockets. He recognized the note of sarcasm.

‘You know my methods, Watson,’ said the doctor.

‘Dead man wearing an overcoat; you conclude he came in the door to find the killer waiting. You guess the two men faced each other squarely with the killer in the chair by the fireplace, and from the path of the wound you guess the gun was in the killer’s left hand.’

‘Damned good cigarettes these Germans give you,’ said the doctor, holding it in the air and looking at the smoke.

‘And an ex-soldier because he pierced the heart with the first shot.’ The doctor inhaled and nodded. ‘Have you noticed that all three of us are still wearing overcoats?’ said Douglas. ‘It’s bloody cold in here and the gas meter is empty and the supply disconnected. And not many soldiers are expert shots, doc, and not one in a million is an expert with a pistol, and by your evidence a German pistol at that. And you think the killer had a key because you can’t see any signs of the door being forced. But my Sergeant could get through that door using a strip of celluloid faster than you could open it with a key, and more quietly too.’

‘Oh,’ said the doctor.

‘Now, what about a time of death?’ said Douglas.

All doctors hate to estimate the time of death and this doctor made sure the policemen knew that. He shrugged. ‘I can think of a number and double it.’

‘Think of a number, doc,’ said Douglas, ‘but don’t double it.’

The doctor, still lolling on the couch, pinched out his cigarette and put the stub away in a dented tobacco tin. ‘I took the temperature when I arrived. The normal calculation is that a body cools one-and-a-half degrees Fahrenheit per hour.’

‘I’d heard a rumour to that effect,’ said Douglas.

The doctor gave him a mirthless grin as he put the tin in his overcoat pocket, and watched his feet as he made the toes touch together again. ‘Could have been between six and seven this morning.’

Douglas looked at the uniformed Sergeant. ‘Who reported it?’

‘The downstairs neighbour brings a bottle of milk up here each morning. He found the door open. No smell of cordite or anything,’ added the Sergeant.

The doctor chortled. When it turned into a cough he thumped his chest. ‘No smell of cordite,’ he repeated. ‘I’ll remember that one, that’s rather rich.’

‘You don’t know much about coppers, doc,’ said Douglas. ‘Specially when you take into account that you are a Police Surgeon. The uniformed Sergeant here, an officer I’ve never met before, is politely hinting to me that he thinks the time of death was earlier. Much earlier, doc.’ Douglas went over to the elaborately painted corner cupboard and opened it to reveal an impressive display of drink. He picked up a bottle of whisky and noted without surprise that most of the labels said ‘Specially bottled for the Wehrmacht’. Douglas replaced the bottles and closed the cupboard. ‘Have you ever heard of postmortem lividity, doctor?’ he said.

‘Death might have been earlier,’ admitted the doctor. He was sitting upright now and his voice was soft. He, too, had noticed the coloration that comes from settling of the blood.

‘But not before midnight.’

‘No, not before midnight,’ agreed the doctor.

‘In other words death took place during curfew?’

‘Very likely.’

‘Very likely?’ said Douglas caustically.

‘Definitely during curfew,’ admitted the doctor.

‘What kind of a game are you playing, doc?’ said Douglas. He didn’t look at the doctor. He went to the fireplace and examined the huge pile of charred paper that was stuffed into the tiny grate. The highly polished brass poker was browned with smoke marks. Someone had used it to make sure that every last piece of paper was consumed by the flames. Again Douglas put his hand into the feathery layers of ash; there must have been a huge pile of foolscap and it was quite cold. ‘Contents of his pockets, Harry?’

‘Identity card, eight pounds, three shillings and tenpence, a bunch of keys, penknife, expensive fountain pen; handkerchief, no laundry marks, and a railway ticket monthly return half; London to Bringle Sands.’

‘Is that all?’

Harry knew that his partner would ask for the identity card and he passed it across unrequested. Harry said, ‘Travelling light, this one.’

‘Or his pockets were rifled,’ said the doctor, not moving from his position on the sofa.

Harry met Douglas’s eyes and there was a trace of a smile. ‘Or his pockets were rifled,’ said Douglas to Harry.

‘That’s right,’ said Harry.

Douglas opened the identity card. It was written there that the holder was a thirty-two-year-old accountant with an address in Kingston, Surrey. ‘Kingston,’ said Douglas.

‘Yes,’ said Harry. They both knew that, ever since the Kingston Records Office had been destroyed in the fighting, this was a favourite address for forgers of identity documents. Douglas put the card in his pocket, and repeated his question. ‘What sort of game are you playing, doctor?’ He looked at the doctor and waited for an answer. ‘Why are you trying to mislead me about the time of death?’

‘Well it was silly of me. But if people are coming and going after midnight the neighbours are supposed to report them to the Feldgendarmerie.’

‘And how do you know that they didn’t report it?’

The doctor raised his hands and smiled. ‘I just guessed,’ he said.

‘You guessed.’ Douglas nodded. ‘Is that because all your neighbours ignore the curfew?’ said Douglas. ‘What other regulations do they regularly flout?’

‘Jesus!’ said the doctor. ‘You people are worse than the bloody Germans. I’d rather talk to the Gestapo than talk to bastards like you – at least they won’t twist everything I say.’

‘It’s not in my power to deny you a chance to talk to the Gestapo,’ said Douglas, ‘but just to satisfy my own vulgar curiosity, doctor, is your opinion about benign interrogation techniques practised by that department based upon first-hand experience or hearsay?’

‘All right, all right,’ said the doctor. ‘Let’s say three A.M.’

‘That’s much better,’ said Douglas. ‘Now you examine the body properly so that I don’t have to wait here for the pathologist before getting started and I’ll forget all about that other nonsense…but leave anything out, doc, and I’ll run you along to Scotland Yard and put you through the mangle. Right?’

‘All right,’ said the doctor.

‘There’s a lady downstairs,’ said the uniformed police Sergeant. ‘She’s come to collect something from the antique shop. I’ve told the Constable to ask her to wait for you.’

‘Good man,’ said Douglas. He left the doctor looking at the body while Harry Woods was going through the drawers of the escritoire.

The antique shop was one of the hundreds that had sprung up since the bombing and the flight of refugees from Kent and Surrey during the weeks of bitter fighting there. With the German Mark pegged artificially high, the German occupiers were sending antiques home by the train-load. The dealers were doing well out of it, but one didn’t need lessons in economics to see the way that wealth was draining out of the country.

There were some fine pieces of furniture in the shop. Douglas wondered how many had been lawfully purchased and how many looted from empty homes. Obviously the owner of the antique shop stored his antiques by putting them in the tiny apartments upstairs, and justified high rents by having them there.

The visitor was sitting on an elegant Windsor chair. She was very beautiful: large forehead, high cheekbones and a wide face with a perfect mouth that smiled easily. She was tall, with long legs and slim arms.

‘Now maybe someone will give me a straight answer.’ She had a soft American voice, and she reached into a large leather handbag and found a US passport, which she brandished at him.

Douglas nodded. For a moment he was spellbound. She was the most desirable woman he’d ever seen. ‘What can I do for you, Madam?’

‘Miss,’ she said. ‘In my country a lady doesn’t like being mistaken for a Madam.’ She seemed amused at his discomfiture. She smiled in that relaxed way that marks the very rich and the very beautiful.

‘What can I do for you, Miss?’

She was dressed in a tailored two-piece of pink wool. Its severe and practical cut made it unmistakably American. It would have been striking anywhere, but in this war-begrimed city, among so many dressed in ill-fitting uniforms or clothes adapted from uniforms, it singled her out as a prosperous visitor. Over her shoulder she carried a new Rolleiflex camera. The Germans sold them tax-free to servicemen and to anyone who paid in US dollars.

‘My name is Barbara Barga. I write a column that is syndicated into forty-two US newspapers and magazines. The press attaché of the German Embassy in Washington offered me a ticket on the Lufthansa inaugural New York to London flight last month. I said yes, and here I am.’

‘Welcome to London,’ said Douglas dryly. It was shrewd of her to mention the inaugural flight on the Focke-Wulf airliner. Göring and Goebbels were both on that flight; it was one of the most publicized events of the year. A journalist would have to be very important indeed to have got a seat.

‘Now tell me what’s going on here?’ she said with a smile. Douglas Archer had not met many Americans, and he’d certainly never met one to compare with this girl. When she smiled, her face wrinkled in a way that Douglas found very beguiling. In spite of himself, he smiled back. ‘Don’t get me wrong,’ she said. ‘I get on well with cops, but I didn’t expect to find so many of them here in Peter’s shop today.’

‘Peter?’

‘Peter Thomas,’ she said. ‘Come on now, mister detective, it says Peter Thomas on the door – Peter Thomas – Antiques – right?’

‘You know Mr Thomas?’ said Douglas.

‘Is he in trouble?’

‘This will go faster if you just answer my questions, Miss.’

She smiled. ‘Who said I wanted to go faster…OK. I know him –’

‘Could you give me a brief description?’

‘Thirty-eight, maybe younger, pale, thin on top, big build, six feet tall, small Ronald Colman moustache, deep voice, good suits.’

Douglas nodded. It was enough to identify the dead man. ‘Could you tell me your relationship with Mr Thomas?’

‘Just business – now what about letting me in on who you are, buddy?’

‘Yes, I’m sorry,’ said Douglas. He felt he was handling this rather badly. The girl smiled at his discomfort. ‘I’m the Detective Superintendent in charge of the investigation. Mr Thomas was found here this morning: dead.’

‘Not suicide? Peter wasn’t the type.’

‘He was shot.’

‘Foul play,’ said the girl. ‘Isn’t that what you British call it?’

‘What was your business with him?’

‘He was helping me with a piece I’m writing about Americans who stayed here right through the fighting. I met him when I came in to ask the price of some furniture. He knew everybody – including a lot of London-based foreigners.’

‘Really.’

‘Peter was a clever man. He’d root out anything anybody wanted, as long as there was a margin in it for him.’ She looked at the collection of silver and ivory objects on a shelf above the cash register. ‘I called this morning to collect some film. I ran out of it yesterday, and Peter said he’d be able to get me a roll. It might have been in his pocket.’

‘There was no film found on the body.’

‘Well, it doesn’t matter. I’ll get some somewhere.’

She was standing near him now and he smelled her perfume. He fantasized about embracing her and – as if guessing this – she looked at him and smiled. ‘Where can I reach you, Miss Barga?’

‘The Dorchester until the end of this week. Then I move into a friend’s apartment.’

‘So the Dorchester is open again?’

‘Just a few rooms at the back. It’s going to be a long time rebuilding the park side.’

‘Make sure you leave a forwarding address,’ said Douglas although he knew that she’d be registered as an alien, and registered with the Kommandantur Press Bureau.

She seemed in no hurry to depart. ‘Peter could get you anything: from a chunk of the Elgin marbles, complete with a letter from the man who dug it out of the Museum wreckage, to an army discharge, category IA – Aryan, skilled worker, no curfew or travel restrictions – Peter was a hustler, Superintendent. Guys like that get into trouble. Don’t expect anyone to weep for him.’

‘You’ve been most helpful, Miss Barga.’ She was going out through the door when Douglas spoke again. ‘By the way,’ he said, ‘do you know if he had been to some hot climate recently?’

She turned. ‘Why?’

‘Sunburned arms,’ said Douglas. ‘As if he’d gone to sleep in the hot sunshine.’

‘I only met him a couple of weeks back,’ said Barbara Barga. ‘But he might have been using a sun-lamp.’

‘That would account for it,’ said Douglas doubtfully.

Upstairs Harry Woods had been talking to Thomas’s only neighbour. He had identified the body and offered the information that Thomas had been a far from ideal neighbour. ‘There was a Luftwaffe Feldwebel…big man with spectacles – I’m not sure what the ranks are – but he was from that Quartermaster’s depot in Marylebone Road. He used to bring all kinds of stuff: tinned food, tobacco and medical stuff too. I think they were selling drugs – always having parties, and you should have seen some of the girls who came here; painted faces and smelling of drink. Sometimes they knocked at my door in mistake – horrible people. I don’t like speaking ill of the dead, mind you, but they were a horrible crowd he was in with.’

‘Do you know if Mr Thomas had a sun-lamp?’ Douglas asked.

‘I don’t know what he didn’t have, Superintendent! A regular Aladdin’s cave you’ll find when you dig into those cupboards. And don’t forget the attic.’

‘No, I won’t, thank you.’

When the man had gone, Douglas took from his pocket the metal object he’d found under the chair. It was made from curved pieces of lightweight alloy, and yet it was clumsy and heavy for its size. It was unpainted and its edge covered with a strip of light-brown leather. It was pierced by a quarter-inch hole, in line with which a screw-threaded nut had been welded. The whole thing was strengthened by a section of tube. From the shape, size and hasty workmanship Douglas guessed it was a part of one of the hundreds of false limbs provided to casualties of the recent fighting. If it was part of a false right arm the doctor might have made a remarkably accurate guess and Douglas could start looking for a left-handed ex-service sharpshooter.

Douglas put the metal construction back into his pocket as Harry came in. ‘You let the doctor go?’ said Douglas.

‘You rode him a bit hard, Doug.’

‘What else did he say?’

‘Three A.M. I think we should try to find this Luftwaffe Feldwebel.’

‘Did the doctor say anything about those sunburns on the arms?’

‘Sun-ray lamp,’ said Harry.

‘Did the doctor say that?’

‘No, I’m saying it. The doctor hummed and hawed, you know what they are like.’

Douglas said, ‘So the neighbour says he was a black-marketeer and the American girl tells us the same thing.’

‘It all fits together, doesn’t it?’

‘It fits together so well that it stinks.’

Harry said nothing.

‘Did you find a sun-ray lamp?’

‘No, but there’s still the attic.’

‘Very well, Harry, have a look in the attic. Then go over to the Feldgendarmerie and get permission to talk to the Feldwebel.’

‘How do you mean it stinks?’ said Harry.

‘The downstairs neighbour tells me everything about this damned Feldwebel short of giving me his name and number. Then this American girl turns up and asks me if I found a roll of film on the body. She tells me that this man Peter Thomas was going to get a roll of film for her last night…ugh! A girl like that would bring a gross of films with her. When she wanted more, she’d get films from a news agency, or from the American Embassy. Failing that, the German Press Bureau would give her as much as she asked for; you know what the propaganda officials will do for American newspaper people. She doesn’t have to get involved with the black market.’

‘Perhaps she wanted to get involved with the black market. Perhaps she is trying to make contact with the Resistance, in order to write a newspaper story.’

‘That’s just what I was thinking, Harry.’

‘What else is wrong?’

‘I took his keys downstairs. None of them fits any of the locks; not the street door or this door. The small keys look like the ones they use on filing cabinets and the bronze one is probably for a safe. There are no filing cabinets here, and if there is a safe, it’s uncommonly well hidden.’

‘Anything else?’ said Harry.

‘If he lives here, why buy a return ticket when he left Bringle Sands yesterday morning? And if he lives here, where are his shirts, his underclothes and his suits?’

‘He left them at Bringle Sands.’

‘And he intended to go to bed here, and then get up and use the same shirt and underclothes, you mean? Look at the body, Harry. This was a man very fussy about his clean linen.’

‘You don’t think he lived here?’

‘I don’t think anyone lived here. This place was just used as somewhere to meet.’

‘Business you mean – or lovers?’

‘You’re forgetting what Resistance people call “safe houses,” Harry. It might have been a place where they met, hid or stored things. And we can’t overlook the way he was wearing his overcoat.’

‘You told the doctor it was cold.’

‘The doctor was trying to irritate me and he succeeded. That doesn’t mean he was wrong about someone sitting here waiting for Thomas to arrive. And it doesn’t explain him keeping his hat on.’

‘I never know what you’re really thinking,’ said Harry.

‘Watch your tongue when you are over at the Feldgendarmerie, Harry.’

‘What do you think I am – stupid?’

‘Romantic,’ said Douglas. ‘Not stupid – romantic.’

‘You think he got those burns from a sun-lamp?’ said Harry.

‘I never heard of anyone going to sleep under a sun-lamp,’ said Douglas, ‘but there has to be a first time for everything. And try to think why someone has taken the light bulb out of that adjustable desk light. There was nothing wrong with the bulb.’

Chapter Four (#u34757546-68c2-5f77-aa05-3a0133075a98)

The beer seemed to get weaker every day and anyone who believed those stories about the fighting having destroyed the hop fields had never tasted the export brands that were selling in German soldiers’ canteens. In spite of its limitations Douglas bought a second pint and smothered the tasteless cheese sandwich with mustard before eating it. There were several other Murder Squad officers in the ‘Red Lion’ in Derby Gate. It was Scotland Yard’s own pub, more crimes had been solved in this bar than in all the offices, path labs and record offices put together, or so some of the regulars claimed, after a few drinks.

A newspaper boy came in selling the Evening Standard. Douglas bought a copy and turned to the Stop Press on the back page.

MAN FOUND DEAD IN WEST END LUXURY FLAT

Shepherd Market in Mayfair was visited by Scotland Yard officers today when the body of a man was discovered by a neighbour bringing the morning pint of milk. The dead man’s name has not yet been released by the police. It is believed that he was an antique dealer and a well-known expert in pearls. Scotland Yard are treating the death as murder, and the investigation is headed by ‘Archer of the Yard’ who solved the grisly ‘Sex-fiend murders’ last summer.

Douglas saw the hand of Harry Woods in that; he knew Douglas hated being called ‘Archer of the Yard’ and Douglas guessed that Harry had spoken over the phone and said the dead man was an ‘expert in girls’ before incredulously denying it on the read-back.

It was raining as Douglas left the ‘Red Lion’. As he looked across the road, at the oncoming traffic, he saw Sylvia, his secretary. She’d obviously been waiting for him. Douglas let a couple of buses pass and then hurried across the road. He waited again for two staff cars flying C-in-C pennants. They hit the ruts left by bomb damage and sprayed water over him. Douglas cursed but that only made it rain harder.

‘Darling,’ said Sylvia. There was not much passion in the word but then with Sylvia there never had been. Douglas put an arm round her and she held her cold face up to be kissed.

‘I’ve been worried all morning. The letter said you were going away.’

‘You must forgive me, darling,’ said Sylvia. ‘I’ve despised myself ever since sending the damned letter. Say you forgive me.’

‘You’re pregnant?’

‘I’m not absolutely sure.’

‘Damn it, Sylvia – you sent the letter and said…’

‘Don’t shout in the street, darling.’ She held a hand up to his mouth. The hand was very cold. ‘Perhaps I shouldn’t have come here?’

‘After three days I had to report your absence. The tea lady asked where you were. It was impossible to cover for you.’

‘I didn’t want you to take any risks, darling.’

‘I phoned your aunt in Streatham but she said she’d not seen you for months.’

‘Yes, I must go and see her.’

‘Will you listen to what I’m saying, Sylvia.’

‘Let go of my arm, you’re hurting me. I am listening.’

‘You’re not listening properly.’

‘I’m listening the same as I always listen to you.’

‘You’ve still got your SIPO pass.’

‘What pass?’

‘Your Scotland Yard pass – have you been drinking or something?’

‘Of course I haven’t been drinking. Well, what about it? You think I’m going to go down Petticoat Lane and sell the bloody pass to the highest bidder? Who the hell wants to go into that hideous building unless they are paid for it?’

‘Let’s walk,’ said Douglas. ‘Don’t you know that Whitehall has regular Gendarmerie patrols?’

‘What are you talking about?’ She smiled. ‘Give me a proper kiss. Aren’t you glad to see me?’

He kissed her hurriedly. ‘Of course I am. We’ll walk up towards Trafalgar Square, all right?’

‘Suits me.’

They walked up Whitehall, past the armed sentries who stood immobile outside the newly occupied offices. They were almost as far as the Whitehall Theatre when they saw the soldiers doing the spot-check. Parked across the roadway there were three Bedford lorries, newly painted with German Army Group L (London District) HQ markings: a crude Tower Bridge surmounting a Gothic L. The soldiers were in battle-smocks with machine pistols slung on their shoulders. They moved quickly, expanding the spiked barrier – designed to pierce tyres – so that only one lane of traffic could pass through in each direction. The check-point command car was parked against the foot of Charles the First’s statue. The Germans learned quickly thought Douglas, for that was the place the Metropolitan Police always used for central London crowd-control work. More soldiers made a barrier behind them.

Sylvia showed no sign of apprehension but she suggested that it would be quicker if they turned off at Whitehall Place and went towards the Embankment. ‘No,’ said Douglas. ‘They always block the side roads first!’

‘I’ll show my pass,’ said Sylvia.

‘Have you gone completely out of your mind?’ said Douglas. ‘The Scotland Yard building houses the SD and the Gestapo and all the rest of it. You might not think much of it, but the Germans think that pass is just about the most valuable piece of paper any foreigner can be given. You’ve stayed away without reporting illness, and you’ve kept your pass. If you read the German regulations that you signed, you’d find that that’s the same as theft, Sylvia. By now, your name and pass number will be on the Gestapo wanted list. Every patrol from Land’s End to John o’Groats will be looking for it.’

‘What shall I do?’ Even now there was no real anxiety in her voice.

‘Stay calm. They have plain-clothes men watching for anyone acting suspiciously.’

They were stopping everything and everyone; staff cars, double-decker buses, even an ambulance was held up while the Patrol Commander examined the papers of the driver and the sick man. The soldiers ignored the rain which made their helmets shiny and darkened their battle-smocks, but the civilians huddled under the protection of the Whitehall Theatre entrance. There was a revue showing there, ‘Vienna Comes to London’, with undressed girls hiding between white violins.

Douglas grabbed Sylvia’s arm and before she could object he brought out a pair of handcuffs and slammed them on her wrist with enough violence to hurt. ‘What are you bloody well doing!’ shouted Sylvia but by that time he was dragging her forward past the waiting people. There were a few muttered complaints as Douglas elbowed them even more roughly. ‘Patrol Commander!’ he shouted imperiously. ‘Patrol Commander!’

‘What do you want?’ said a pimply young Feldwebel wearing the metal breastplate that was the mark of military police on duty. He was not wearing a battle-smock and Douglas guessed he was a section leader. He waved his SIPO pass in the air, and spoke in rapid German. ‘Wachtmeister! I’m taking this girl for questioning. Here’s my pass.’

‘Her papers?’ said the youth impassively.

‘Says she’s lost them.’

He didn’t react except to take the pass from Douglas and examine it carefully before looking at his face and his photo to compare them.

‘Come along, come along,’ said Douglas on the principle that no military policeman is able to distinguish between politeness and guilt. ‘I’ve not got all day.’

‘You’ve hurt my bloody wrist,’ said Sylvia. ‘Look at that, you bastard.’ The Feldwebel glared at him and then at the girl. ‘Next!’ he bellowed.

‘Come on,’ said Douglas and hurried through the barrier dragging Sylvia after him. They picked their way through the traffic that was waiting for the checkpoint. They were both very wet and neither spoke as a luxury bus came through Admiralty Arch and into Trafalgar Square. Its windows were crowded with the faces of young soldiers. Softly from inside there came the amplified voice of the tour guide speaking schoolboy German. The young men grinned at his pronunciation. One boy waved at Sylvia.

A few wet pigeons shuffled out of the way as they walked across the empty rainswept square. ‘Do you realize what you said, just now?’ said Sylvia. She was still rubbing her wrist where the skin had been grazed.

It was just like a woman, thought Douglas, to start some oblique conversation about something already forgotten.

‘One of the most important pieces of paper that the Germans issue to foreigners; that’s what you said just now.’

‘Give over, Sylvia,’ said Douglas. He looked back to be sure they were out of sight of the patrol, then he unlocked the handcuff and released her arm.

‘That’s what we are as far as you’re concerned –foreigners! The Germans are the ones with a right to be here; we’re the intruders who have to bow and bloody scrape.’

‘Give over, Sylvia,’ said Douglas. He hated to hear women swearing like that, although, working in a police force, he should by now have got used to it.

‘Get your hands off me, you bloody Gestapo bastard.’ She pushed him away with the flat of her hand. ‘I’ve got friends who don’t go in fear and trembling of the Huns. You wouldn’t understand anything about that, would you. No! You’re too busy doing their dirty work for them.’

‘You must have been talking to Harry Woods,’ said Douglas in a vain attempt to turn the argument into a joke.

‘You’re pathetic,’ said Sylvia. ‘Do you know that? You’re pathetic!’

She was pretty, but with the rain making rats’ tails of her hair, her lipstick smudged, and the ill-fitting raincoat that had always been too short for her, Douglas suddenly saw her as he’d never seen her before. And he saw her, too, as she’d be in ten years hence; a tight-lipped virago with a loud voice and quick temper. He realized that he’d never make a go of it with Sylvia. But when her parents were killed by bombs, just a few days before Douglas lost his wife, it was natural that they sought in each other some desperate solace that came disguised as love.

What Douglas had once seen as the attractive over-confidence of youth, now looked more like unyielding selfishness. He wondered if there was another man, a much younger one perhaps, but decided against asking her, knowing that she would say yes just to annoy him. ‘We’re both pathetic, Sylvia,’ he said, ‘and that’s the truth of it.’

They were standing near one of the Landseer lions, shining as black as polished ebony in the driving rain. They were virtually alone there, for now even the most stalwart of German servicemen had put away their tax-free cameras and taken shelter. Sylvia stood with one hand in her pocket, and the other pushing her wet hair off her forehead. She smiled but there was no merriment there, not even a touch of kindness or compassion. ‘Don’t be sarcastic about Harry Woods,’ she said bitterly. ‘He’s the only friend you’ve got left. Do you realize that?’

‘Leave Harry out of it,’ said Douglas.

‘You realize he’s one of us, don’t you?’

‘What?’

‘The Resistance, you fool.’ The expression on Douglas’s face was enough to make her laugh. A woman, pushing a pram laden with a sack of coal, half turned to look at them before hurrying on.

‘Harry?’

‘Harry Woods, assistant to Archer of the Yard, protégé of the Gestapo, scourge of any who dare blow raspberries at the conqueror, and yet, yea, verily, I say unto you, this man dare fight the bloody Hun.’ She walked to the fountain and looked at her reflection in the shallow waters.

‘You have been drinking.’

‘Only the heady potion of freedom.’

‘Don’t take an overdose,’ said Douglas. It was almost comical to see her in this sort of mood. Perhaps it was a reaction to the fear she’d felt at the spot-check.

‘Just look after our friend Harry,’ she called shrilly, ‘and give him this, with all my love.’

The hand emerged from her pocket holding the SIPO pass. Before Douglas could stop her, she lifted her arm and threw it as far as she could into the water of the fountain. The rain pounded the stone paving so heavily that the water rebounded to make a grey cornfield of water-spray. She walked quickly through it, towards the steps that led to the National Gallery.

Under the rain-spotted water it was only just possible to see the red-bordered pass as it sank to the bottom amongst the tourists’ coins, Agfa boxes and ice-cream wrappers. Left there, it might well be spotted by some high-ranking official, who would make life hell for the whole department. Douglas stood looking at it for a moment or two but he was already so wet that it would make little difference to go into the water up to his knees.

Chapter Five (#u34757546-68c2-5f77-aa05-3a0133075a98)

When Douglas got back to his office that afternoon, he had barely enough time to clean himself up, and put on dry shoes, before there was a message from the first floor. General Kellerman wanted a word with Douglas, if that was convenient. It was convenient. Douglas hurried upstairs.

‘Ah, Superintendent Archer, so good of you to come,’ said Kellerman as if Archer was some sort of visiting dignitary. ‘I seem to have such a busy day today.’ Kellerman’s senior staff officer passed his chief a teleprinter sheet. Kellerman looked at it briefly and said, ‘This chap from Berlin, Standartenführer Huth…you remember?’

‘I remember everything you said, sir.’

‘Splendid. Well, the Standartenführer has been given a priority seat on the afternoon Berlin-Croydon flight. He’ll be arriving about five I should think. I wonder if you would go there and meet him?’

‘Yes, sir, but I wonder…’ Douglas couldn’t think of a good way to suggest that an SS-Standartenführer from Himmler’s Central Security Office would consider a welcome from one English Detective Superintendent less than his rank and position merited.

‘The Standartenführer has requested that you meet him,’ said Kellerman.

‘Me personally?’ said Douglas.

‘His task is of an investigative nature,’ said Kellerman. ‘I thought it appropriate that I assign to him my best detective.’ He smiled. In fact Huth had asked for Archer by name. Kellerman had energetically opposed the order that put Douglas Archer under the command of the new man, but the intervention of Himmler himself had ended the matter.

‘Thank you, sir,’ said Douglas.

Kellerman reached into the pocket of his tweed waistcoat and looked at his gold pocket watch. ‘I’ll start right away,’ said Douglas, recognizing his cue.

‘Would you?’ said Kellerman. ‘Well, see my personal assistant so that you know all the arrangements we’ve made to receive the Standartenführer.’

Lufthansa had three Berlin–London flights daily, and these were additional to the less comfortable and less prestigious military flights. Standartenführer Dr Oskar Huth had been given one of the fifteen seats on the flight which left Berlin at lunch time.

Douglas waited in the unheated terminal building and watched a Luftwaffe band preparing for the arrival of the daily flight from New York. The Germans had the only land-planes capable of such a long-range, non-stop service and the Propaganda Ministry was making full use of it.

The rain had continued well into the afternoon but now on the horizon there was a break in the low clouds. The Berlin plane circled, while the pilot decided whether to land. After the third circuit the big three-engined Junkers roared low over the airport building, and then came round for a perfect landing on the wet tarmac. Its hand-polished metal flashed as it taxied back to the terminal building.

Douglas half expected that any man who had his doctorate included with his rank on teleprinter messages might have retained a trace of the bedside manner. But Huth was a doctor of law, and a hard-nosed SS officer if Douglas had ever seen one. And by that time Douglas had seen many.

Unlike Kellerman, the new man was wearing his uniform, and gave no sign of preferring plain clothes. It was not the black SS uniform. That nowadays was worn only by the Allgemeine SS – mostly middle-aged country yokels who donned uniform just for village booze-ups at weekends. Dr Huth’s uniform was silver-grey, with high boots and riding breeches. On his cuff there was the RFSS cuffband worn only by Himmler’s personal staff.