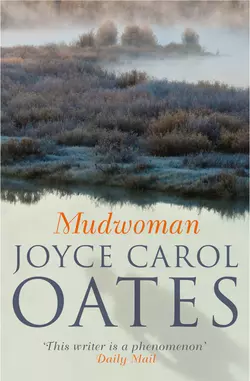

Mudwoman

Joyce Carol Oates

A haunting new novel from one of America’s most prolific and respected novelists.Mudgirl is a child abandoned by her mother in the silty flats of the Black Snake River. Cast aside, Mudgirl survives by an accident of fate - or destiny. After her rescue, she will slowly forget her own origin, her past erased, her future uncertain. The well-meaning couple who adopt Mudgirl quarantine her poisonous history behind the barrier of their Quaker values: compassion, modesty, and hard work - seemingly sealing it off forever. But the bulwark of the present proves surprisingly vulnerable to the agents of the past.Meredith ‘M.R.’ Neukirchen is the first woman president of a prestigious Ivy League university whose commitment to her career and moral fervor for her role are all-consuming. Involved with a secret lover whose feelings for her are teasingly undefined, concerned with the intensifying crisis of the American political climate as the United States edges toward a declaration of war with Iraq, M.R. is confronted with challenges to her professional leadership which test her in ways she could not have expected. The fierce idealism and intelligence that delivered her from a more conventional life in her upstate New York hometown now threaten to undo her.A reckless trip upstate thrusts M.R. Neukirchen into an unexpected psychic collision with Mudgirl and the life M.R. believes she has left behind. A powerful exploration of the enduring claims of the past, ‘Mudwoman’ is at once a psychic ghost story and an intimate portrait of an individual who breaks - but finds a way to heal herself.

Mudwoman

Joyce Carol Oates

Dedication

For Charlie Gross,

my husband and

first reader

Epigraph

What is man? A ball of snakes.

FRIEDRICH NIETZSCHE,

Thus Spake Zarathustra

Here the frailest leaves of me and yet my strongest lasting,

Here I shade and hide my thoughts, I myself do not expose them,

And yet they expose me more than all my other poems.

WALT WHITMAN,

“Here the Frailest Leaves of Me”

Time is a way of preventing all things from happening at once.

ANDRE LITOVIK,

“The Evolving Universe: Origin, Age & Fate”

Contents

Cover (#ulink_c62f2f5d-a5b2-5b88-8907-c8898ac97c32)

Title Page

Dedication

Epigraph

Mudgirl in the Land of Moriah.

Mudwoman’s Journey. The Black River Café.

Mudgirl Saved by the King of the Crows.

Mudwoman Confronts an Enemy. Mudwoman’s Triumph.

Mudgirl Reclaimed. Mudgirl Renamed.

Mudwoman Fallen. Mudwoman Arisen. Mudwoman in the Days of Shock and Awe.

Mudgirl in “Foster Care.” Mudgirl Receives a Gift.

Mudwoman Makes a Promise. And Mudwoman Makes a Discovery.

Mudgirl Has a New Home. Mudgirl Has a New Name.

Mudwoman Mated.

Mudgirl, Cherished.

Mudwoman, Bereft.

Mudgirl, Desired.

Mudwoman, Challenged.

Mudgirl: Betrayal.

Mudwoman in Extremis.

Mudwoman Ex Officio.

Mudwoman Amid the Nebulae.

Mudwoman Flung to Earth.

Mudwoman Bride.

Mudwoman Finds a Home.

Mudwoman Encounters a Lost Love.

Mudwoman: Moons beyond Rings of Saturn.

Mudwoman Not Struck by Lightning. Mudwoman Saved from Nightmare.

Mudwoman at Star Lake. Mudwoman at Lookout Point.

About the Author

Other Books by the Same Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

Mudgirl in the Land of Moriah.

April 1965

You must be readied, the woman said.

Readied was not a word the child comprehended. In the woman’s voice readied was a word of calm and stillness like water glittering in the mudflats beside the Black Snake River the child would think were the scales of a giant snake if you were so close to the snake you could not actually see it.

For this was the land of Moriah, the woman was saying. This place they had come to in the night that was the place promised to them where their enemies had no dominion over them and where no one knew them or had even glimpsed them.

The woman spoke in the voice of calm still flat glittering water and her words were evenly enunciated as if the speaker were translating blindly as she spoke and the words from which she translated were oddly shaped and fitted haphazardly into her larynx: they would give her pain, but she was no stranger to pain, and had learned to find a secret happiness in pain, too wonderful to risk by acknowledging it.

He is saying to us, to trust Him. In all that is done, to trust Him.

Out of the canvas bag in which, these several days and nights on the meandering road north out of Star Lake she’d carried what was needed to bring them into the land of Moriah safely, the woman took the shears.

In her exhausted sleep the child had been hearing the cries of crows like scissors snipping the air in the mudflats beside the Black Snake River.

In sleep smelling the sharp brackish odor of still water and of rich dark earth and broken and rotted things in the earth.

A day and a night on the road beside the old canal and another day and this night that wasn’t yet dawn at the edge of the mudflats.

Trust Him. This is in His hands.

And the woman’s voice that was not the woman’s familiar hoarse and strained voice but this voice of detachment and wonder in the face of something that has gone well when it was not expected, or was not expected quite so soon.

If it is wrong for any of this to be done, He will send an angel of the Lord as He sent to Abraham to spare his son Isaac and also to Hagar, that her son was given back his life in the wilderness of Beersheba.

In her stubby fingers that were chafed and bled easily after three months of the gritty-green lye-soap that was the only soap available in the county detention facility the woman wielded the large tarnished seamstress’s shears to cut the child’s badly matted hair. And with these stubby fingers tugging at the hair, in sticky clumps and snarls the child’s fine fawn-colored hair that had become “nasty” and “smelly” and “crawling with lice.”

Be still! Be good! You are being readied for the Lord.

For our enemies will take you from me, if you are not readied.

For God has guided us to the land of Moriah. His promise is no one will take any child from her lawful mother in this place.

And the giant shears clipped and snipped and clattered merrily. You could tell that the giant shears took pride in shearing off the child’s befouled hair that was disgusting in the sight of God. Teasingly close to the girl’s tender ears the giant shears came, and the child shuddered, and squirmed, and whimpered, and wept; and the woman had no choice but to slap the child’s face, not hard, but hard enough to calm her, as often the woman did; hard enough to make the child go very still the way even a baby rabbit will go still in the cunning of terror; and then, when the child’s hair lay in wan spent curls on the mud-stained floor, the woman drew a razor blade over the child’s head—a blade clutched between her fingers, tightly—causing the blade to scrape against the child’s hair-stubbled scalp and now the child flinched and whimpered louder and began to struggle—and with a curse the woman dropped the razor blade which was badly tarnished and covered with hairs and the woman kicked it aside with a harsh startled laugh as if in wishing to rid the child of her snarly dirty hair that was shameful in the eyes of God the woman had gone too far, and had been made to recognize her error.

For it was wrong of her to curse—God damn!

To take the name of the Lord in vain—God damn!

For in the Herkimer County detention facility the woman had taken a vow of silence in defiance of her enemies and she had taken a vow of utter obedience to the Lord God and these several weeks following her release, until now she had not betrayed this vow.

Not even in the Herkimer County family court. Not even when the judge spoke sharply to her, to speak—to make a plea of guilty, not guilty.

Not even when the threat was that the children would be taken forcibly from her. The children—the sisters—who were five and three—would be wards of the county and would be placed with a foster family and not even then would the woman speak for God suffused her with His strength in the very face of her enemies.

And so the woman took up a smaller scissors, out of the canvas bag, to clip the child’s fingernails so short the tender flesh beneath the nails began to bleed. Though the child was frightened she managed to hold herself still except for shivering as the baby rabbit will hold itself still in the desperate hope that is most powerful in living creatures, our deepest expectation in the face of all evidence refuting it, that the terrible danger will pass.

For—maybe—this was a game? What the spike-haired man called a game? Secret from the woman was the little cherry pie—sweet cherry pie in a wax-paper package small enough to fit into the palm of the spike-haired man’s hand—so delicious, the child devoured it greedily and quickly before it might be shared by another. There was splash-splash which was bathing the child in the claw-footed tub while the woman slept in the next room on the bare mattress on the floor her limbs sprawled as if she’d fallen from a height onto her back moaning in her sleep and waking in a paroxysm of coughing as if she were coughing out her very guts. Bathing the child who had not been bathed in many days and mixed with the bathing was the game of tickle. So carefully!—as if she were a breakable porcelain doll and not a tough durable rubber doll like Dolly you’d just bang around, let fall onto the floor and kick out of your way if she was in your way—and so quietly!—the spike-haired man carried the child into the bathroom and to the claw-footed tub that was the size of a trough for animals to drink from and in the bathroom with the door shut—forcibly—for the door was warped and the bolt could not be slid in place—the spike-haired man stripped the child’s soiled pajamas from her and set her—again so carefully!—a forefinger pressed to his lips to indicate how carefully and without noise this must be—set her into the tub—into the water that sprang from the faucet tinged with rust and was only lukewarm and there were few soap bubbles except when the spike-haired man rubbed his hands vigorously together with the bar of nice-smelling Ivory soap between his palms and lathered the suds on the child’s squirmy little pale body like something soft prized out of its shell in what was the game of tickle—the secret game of tickle; and amid the splashing soon the water cooled and had to be replenished from the faucet—but the faucet made a groaning sound as if in protest and the spike-haired man pressed his forefinger against his lips pursed like a TV clown’s lips and his raggedy eyebrows lifted to make the child laugh—or, if not laugh, to make the child cease squirming, struggling—for the game of tickle was very ticklish!—the spike-haired man laughed a near-soundless hissing laugh and soon after lapsed into an open-mouthed doze having lost the energy that rippled through him like electricity through a coil and the child waited until the spike-haired man was snoring half-sitting half-lying on the puddled floor of the bathroom with his back against the wall and water-droplets glistening in the dense wiry steel-colored hairs on his chest and on the soft flaccid folds of his belly and groin and when finally in the early evening when the spike-haired man awakened—and when the woman sprawled on the mattress in the adjacent room awakened—the child had climbed out of the tub naked and shivering and her skin puckered and white like the skin of a defeathered chicken and for a long time the woman and the spike-haired man searched for her until she was discovered clutching at her ugly bareheaded rubber doll curled up like a stepped-on little worm in skeins of cobweb and dustballs beneath the cellar stairs.

Hide-and-seek! Hide-and-seek and the spike-haired man was the one to find her!

For what were the actions of adults except games, and variants of games. The child was given to know that a game would come to an end unlike other actions that were not-games and could not be ended but sprawled on and on like a highway or a railroad track or the river rushing beneath the loose-fitting planks of the bridge near the house in which she and the woman had lived with the spike-haired man before the trouble.

This is not hurting you! You will defame God if you make such a fuss.

The woman’s voice was not so calm now but raw-sounding like something that has been broken and gives pain. And the woman’s fingers on the child were harder, and the broken and uneven nails were sharp as a cat’s claws digging into the child’s flesh.

The child’s tender scalp was bleeding. The hairs remaining were stubbled. Amid the remaining sticky strands of hair haphazardly cut and partly shaved were tiny frantic lice. By this time the child’s soiled clothes had been removed, wadded into a ball and kicked aside. It was a tar paper cabin the woman had discovered in the underbrush between the road and the towpath. The sign from God directing her to this abandoned place had been a weatherworn toppled-over cross at the roadside that was in fact a mileage marker so faded you could not make out the words or the numerals but the woman had seen M O R I A H.

In this foul place where they had slept wrapped in the woman’s rumpled and stained coat there was no possibility of bathing the child. Nor would there have been time to bathe the child, for God was growing impatient now it was dawn which was why the woman’s hands fumbled and her lips moved in prayer. The sky was growing lighter like a great eye opening and in most of the sky that you could see were clouds massed and dense like chunks of concrete.

Except at the tree line on the farther side of the mudflats where the sun rose.

Except if you stared hard enough you could see that the concrete clouds were melting away and the sky was layered in translucent faint-red clouds like veins in a great translucent heart that was the awakening of God to the new dawn in the land of Moriah.

In the car the woman had said I will know when I see. My trust is in the Lord.

The woman said Except for the Lord, everything is finished.

The woman was not speaking to the child for it was not her practice to speak to the child even when they were alone. And when they were in the presence of others, the woman had ceased speaking at all and it was the impression of those others who had no prior knowledge of the woman that she was both mute and deaf and very likely had been born so.

In the presence of others the woman had learned to shrink inside her clothing that hung loosely on her for at the time of her pregnancies she had been ashamed and fearful of the eyes of strangers moving on her like X-rays and so she had acquired men’s clothing that hid her body—though around her neck in a loose knot, for her throat was often painful, and she feared strep throat, was a scarf of some shiny crinkly purple material she had found discarded.

The child was naked inside the paper nightgown. The child was bleeding from her razor-lacerated scalp in a dozen tiny wounds and shivering and naked inside the pale green paper nightgown faintly stamped HERKIMER CO. DETENTION that had been cut by the giant shears to reduce its length if not its width so that the paper nightgown came to just the child’s skinny ankles.

A paper gown to be tracked to the Herkimer County medical unit attached to the women’s detention home.

In the rear seat of the rattling rusted Plymouth which was the spike-haired man’s sole legacy was the child’s rubber doll. Dolly was the name of the doll that had been her sister’s and was now hers. Dolly’s face was soiled and her eyes had ceased to see. Dolly’s small mouth was a pucker in the grim rubber flesh. And Dolly too was near-bald, only patches of curly fair hair remaining where you could see how the sad feathery fawn-colored hairs had been glued to the rubber scalp.

Seventy miles north of Star Lake as remote to the woman and the child as the farther, eclipsed half of the moon, the shadowed mudflats beside the river.

So meandering and twisting were the mountain roads, a journey of merely seventy miles had required days, for the woman feared to drive the rattling automobile at any speed beyond thirty. And urgent to her too, that her obedience to God was manifest in this slowness and in this deliberateness like one who can only read by drawing his forefinger beneath each letter of each word to be enunciated aloud.

The child did not fret. But the woman believed, in her heart the child did fret for both the children were rebellious. No comb could be forced through such snarled hair.

In harsh jeering cries the crows reviled God.

Jeering demanding to know as the (female, middle-aged) judge had demanded to know why these children have been found filthy and partly clothed pawing through a Dumpster behind the Shop-Rite scavenging for food like stray dogs or wild creatures shrinking in the beam of a flashlight. And the elder of the sisters clutching at the hand of the younger and would not let go.

And how does the mother explain and how does the mother plead.

Proudly the woman stood and her chin uplifted and eyes shut against the Whore of Babylon there in black robes but a lurid lipstick-mouth and plucked eyebrows like arched insect wings. No more would the woman plead than fall to her knees before this whorish vision.

The children had been taken from her and placed in temporary custody of the county. But the will of God was such, all that was rightfully the woman’s was restored to her, in time.

In all those weeks, months—the woman had never weakened in her faith that all that was hers, would be restored to her.

And now at dawn the sky in the east was ever-shifting, expanding. The gray concrete-sky that is the world-bereft-of-God was retreating. Almost you could see angels of wrath in these broken clouds. Glittering light in the stagnant strips of water of the mudflats of the hue of watery blood. Less than a half mile from the Black Snake River in a desolate area of northeastern Beechum County in the foothills of the Adirondacks, where the hand of God had guided her. Here were the remains of an abandoned mill, an unpaved road and rotted debris amid tall snakelike marsh grasses that shivered and whispered in the wind. Exposed roots of trees and collapsed and rotting tree trunks bearing the whorled and affrighted faces of the damned. And what beauty in such forlorn places, Mudgirl would cherish through her life. For we most cherish those places to which we have been brought to die but have not died. No smells more pungent than the sharp muck-smell of the mudflats where the brackish river water seeps and is trapped and stagnant with algae the bright vivid green of Crayola. Vast unfathomable acres of mudflats amid cattails, jimsonweed and scattered litter of old tires, boots, torn clothing, broken umbrellas and rotted newspapers, abandoned stoves, refrigerators with doors flung open like empty arms. Seeing a small squat refrigerator tossed on its side in the mud the child thought She will put us inside that one.

But something was wrong with this. The thought came a second time, to correct—She has put us inside that one. She has shut the door.

There came a frenzy of crows, red-winged blackbirds, starlings, as if the child had spoken aloud and said a forbidden thing.

The woman cried shaking her fist at the birds, God will curse you!

The raucous accusing cries grew louder. More black-feathered birds appeared, spreading their great wings. They settled in the skeletal trees fierce and clattering. The woman cried, cursed and spat and yet the bird-shrieks continued and the child was given to know that the birds had come for her.

These were sent by Satan, the woman said.

It was time, the woman said. A day and a night and another day and now the night had become dawn of the new day and it was time and so despite the shrieking birds the woman half-walked half-carried the child in the torn paper nightgown in the direction of the ruined mill. Pulling at the child so that the child’s thin pale arm felt as if it were about to be wrenched out of its socket.

The woman made her way beyond the ruined mill which smelled richly of something sweetly rancid and fermented and into an area of broken bricks and rotted lumber fallen amid rich dark muddy soil and spiky weeds grown to the height of children. In her haste she startled a long black snake sleeping in the rotted lumber but the snake refused to crawl away rapidly instead moving slowly and sinuously out of sight in defiance of the intruder. At first the woman paused—the woman stared—for the woman was awaiting an angel of God to appear to her—but the sinuous black-glittering snake was no angel of God and in a fury of hurt, disappointment and determination the woman cried, Satan go back to hell where you came from but already in insolent triumph the snake had vanished into the underbrush.

The child had ceased whimpering, for the woman had forbade her. The child barefoot and naked inside the rumpled and torn pale green paper gown faintly stamped HERKIMER CO. DETENTION. The child’s legs were very thin and stippled with insect bites and of these bites many were bleeding, or had only recently ceased bleeding. The child’s head near-bald, stubbled and bleeding and the eyes dazed, uncomprehending. At the end of a lane leading to the canal towpath was a spit of land gleaming with mud the hue of baby shit and tinged with a sulfurous yellow: and the smell was the smell of baby shit for here were many things rotted and gone. Faint mists rose from the interior of the marsh like the exhaled breaths of dying things. The child began to cry helplessly. As the woman hauled her along the land-spit the child began to struggle but could not prevail. The child was weak from malnutrition yet still the child could not have prevailed for the woman was strong and the strength of God flowed through her being like a bright blinding beacon. Light flared off the woman’s face, she had never been so certain of herself and so joyous in certainty as now. For knowing now that the angel of God would not appear to her as the angel of God had appeared to both Abraham and Hagar who had borne Abraham’s child and had been cast into the wilderness by Abraham with the child to die of thirst.

And this was not the first time the angel of God had been withheld from her. But it would be the last time.

With a bitter laugh the woman said, Here, I am returning her to You. As You have bade me, so I am returning her to You.

First, Dolly: the woman pried Dolly from the child’s fingers and tossed Dolly out into the mud.

Here! Here is the first of them.

The woman spoke happily, harshly. The rubber doll lay astonished in the mud below.

Next, the child: the woman seized the child in her arms to push her off the spit of land and into the mud—the child clutched at her only now daring to cry Momma! Momma!—the woman pried the child’s fingers loose and pushed, shoved, kicked the child down the steep incline into the flat glistening mud below close by the ugly rubber doll and there the child flailed her thin naked limbs, on her belly now and her small astonished face in the mud so the cry Momma was muffled and on the bank above the woman fumbled for something—a broken tree limb—to swing at the child for God is a merciful God and would not wish the child to suffer but the woman could not reach the child and so in frustration threw the limb down at the child for all the woman’s calmness had vanished and she was now panting, breathless and half-sobbing and by this time though the ugly rubber doll remained where it had fallen on the surface of the mud the agitated child was being sucked down into the mud, a chilly bubbly mud that would warm but grudgingly with the sun, a mud that filled the child’s mouth, and a mud that filled the child’s eyes, and a mud that filled the child’s ears, until at last there was no one on the spit of land above the mudflat to observe her struggle and no sound but the cries of the affronted crows.

Mudwoman’s Journey. The Black River Café.

October 2002

Readied. She believed yes, she was.

She was not one to be taken by surprise.

“Carlos, stop! Please. Let me out here.”

In the rearview mirror the driver’s eyes moved onto her, startled.

“Ma’am? Here?”

“I mean—Carlos—I’d like to stop for just a minute. Stretch my legs.”

This was so awkwardly phrased, and so seemingly fraudulent—stretch my legs!

Politely the driver protested: “Ma’am—it’s less than an hour to Ithaca.”

He was regarding her with a look of mild alarm in the rearview mirror. Very much, she disliked being observed in that mirror.

“Please just park on the shoulder of the road, Carlos. I won’t be a minute.”

Now she did speak sharply.

Though continuing to smile of course. For it was unavoidable, in this new phase of her life she was being observed.

The bridge!

She had never seen the bridge before, she was sure. And yet—how familiar it was to her.

It was not a distinguished or even an unusual bridge but an old-style truss bridge of the 1930s, with a single span: wrought-iron girders marked with elaborate encrustations of rust like ancient and unreadable hieroglyphics. Already M.R. knew, without needing to see, that the bridge was bare planking and would rattle beneath crossing vehicles; all of the bridge would vibrate finely, like a great tuning fork.

Like the bridges of M.R.’s memory, this bridge had been built high above the stream below, which was a small river, or a creek, that flooded its banks after rainstorms. To cross the bridge you had to ascend a steep paved ramp. Both the bridge and the ramp were narrower by several inches than the two-lane state highway that led to the bridge and so in its approach to the bridge the road conspicuously narrowed and the shoulder was sharply attenuated. All this happened without warning—you had to know the bridge, not to blunder onto it when a large vehicle like a van or a truck was crossing.

There was no shoulder here upon which to park safely, at least not a vehicle the size of the Lincoln Town Car, but canny Carlos had discovered an unpaved service lane at the foot of the bridge ramp, that led to the bank of the stream. The lane was rutted, muddy. In a swath of underbrush the limousine came to a jolting stop only a few yards from rushing water.

Some subtle way in which the driver both obeyed his impulsive employer, and resisted her, made M.R.’s heart quicken in opposition to him. Clearly Carlos understood that this was an imprudent stop to have made, within an hour of their destination; the very alacrity with which he’d driven the shiny black limousine off the road and into underbrush was a rebuke to her, who had issued a command to him.

“Carlos, thank you. I won’t be a—a minute …”

Won’t be a minute. Like stretch my legs this phrase sounded in her ears forced and alien to her, as if another spoke through her mouth, and M.R. was the ventriloquist’s dummy.

Quickly before Carlos could climb out of the car to open the door for her, M.R. opened the door for herself. She couldn’t seem to accustom herself to being treated with such deference and formality!—it wasn’t M.R.’s nature.

M.R., whom excessive attention and even moderate flattery embarrassed terribly; as if, by instinct, she understood the mockery that underscores formality.

“I’ll be right back! I promise.”

She spoke cheerily, gaily. M.R. couldn’t bear for any employee—any member of her staff—to feel uncomfortable in her presence.

As, teaching, when she’d approach a seminar room hearing the voices and laughter of the students inside, she’d hesitate to intrude—to evoke an abrupt and too-respectful silence.

Her power over others was that they liked her. Such liking could only be volitional, free choice.

She was walking along the embankment thinking these thoughts. By degrees the rushing water drowned out her thoughts—hypnotic, just slightly edgy. There is always a gravitational pull toward water: to rushing water. One is drawn forward, one is drawn in.

Now. Here. Come. It is time….

She smiled hearing voices in the water. The illusion of voices in the water.

But here was an impediment: the bank was tangled with briars, vines. An agonized twisting of something resembling guts. It wasn’t a good idea for M.R. to be walking in her charcoal-gray woolen trousers and her pinching-new Italian shoes.

Yet if you looked closely, with a child’s eye, you could discern a faint trail amid the underbrush. Children, fishermen. Obviously, people made their way along the stream, sometimes.

A nameless stream—creek, or river. Seemingly shallow, yet wide. A sprawl of boulders, flat shale-like rock. Froth of the hue and seeming substance of the most nouveau of haute cuisine—foam-food, pureed and juiced, all substance leached from it, terrible food! Tasteless and unsatisfying and yet M.R. had been several times obliged to admire it, dining at the Manhattan homes of one or another of the University’s wealthy trustees, who kept in their employ full-time chefs.

The creek, or river, was much smaller than the Black Snake River that flowed south and west out of the southern Adirondacks, traversing Beechum County at a diagonal—the river of M.R.’s childhood. Yet—here was the identical river-smell. If M.R. shut her eyes and inhaled deeply, she was there.

Here was an odor of something brackish and just slightly sour—rancid/rotted—decaying leaves—rich damp dark earth that sank beneath her heels as she made her way along the bank, shading her eyes against the watery glitter like tinfoil.

Mingled with the river-smell was an odor of something burning, like rubber. Smoldering tires, garbage. A wet-feather smell. But faint enough that it wasn’t unpleasant.

All that M.R. could see—on the farther bank of the stream—was a wall of dark-brick buildings with only a few windows on each floor; and beyond the windows, nothing visible. High on the sides of the buildings were advertisements—product names and pictures of—faces? human figures?—eroded by time and now indecipherable, lost to all meaning.

“‘Mohawk Meats and Poultry.’”

The words came to her. The memory was random, and fleeting.

“‘Boudreau Women’s Gloves and Hosiery.’”

But that had been Carthage, long ago. These ghost-signs, M.R. could not read at all.

Carlos was surely correct, they weren’t far from the small city of Ithaca—which meant the vast sprawling spectacular campus of Cornell University where M.R. had been an undergraduate twenty years before and had graduated summa cum laude, in another lifetime. Yet she had no idea of the name of this small town or where exactly they were except south and west of Ithaca in the glacier-ravaged countryside of Tompkins County.

It was a bright chilly October day. It was a day splotched with sumac like bursts of flame.

The not-very-prosperous small town of faded-brick storefronts and cracked sidewalks reminded M.R. of the small city in which she’d grown up in Beechum County in the foothills of the southern Adirondacks. Vaguely she was thinking I should have planned to visit them. It has been so long.

Her father lived there still—in Carthage.

She had not told Konrad Neukirchen that she would be spending three nights within a hundred miles of Carthage since virtually every minute of the conference would be filled with appointments, engagements, panels, talks—and yet more people would request time with M.R., once the conference began. She had not wanted to disappoint her father, who’d always been so proud of her.

Her father, and also her mother of course. Both the Neukirchens: Konrad and Agatha.

How painful it was to M.R., to disappoint others! Her elders, who’d invested so much in her. Their love for her was a heavy cloak upon her shoulders, like one of those lead-shield cloaks laid upon you in the dentist’s office to shield you from X-rays—you were grateful for the cloak but more grateful when it was removed.

Far rather would M.R. be disappointed by others, than to be the agent of disappointment herself. For M.R. could forgive—readily; she was very good at forgiveness.

She was very good at forgetting, also. To forget is the very principle of forgiveness.

Perhaps it was a Quaker principle, or ought to have been, which she’d inherited from her parents: forget, forgive.

Boldly now she walked on the bank of the nameless river amid broken things. An observer on the bridge some distance away would have been surprised to see her: a well-dressed woman, alone, in this place so impractical for walking, amid a slovenly sort of quasi-wilderness. M.R. was a tall woman whom an erect backbone and held-high head made taller—a woman of youthful middle-age with an appealingly girlish face—fleshy, flush-cheeked. Her eyes were both shy and quick-darting, assessing. In fact the eyes were a falcon’s eyes, in a girl’s face.

How strange she felt in this place! The glittery light—lights—reflected in the swift-running water seemed to suffuse her heart. She felt both exhilarated and apprehensive, as if she were approaching danger. Not a visible danger perhaps. Yet she must go forward.

This was a common feeling of course. Common to all who inhabit a “public” role. She would be addressing an audience in which there was sure to be some opposition to her prepared words.

Her keynote address, upon which she’d worked intermittently, for weeks, was only to be twenty minutes long: “The Role of the University in an Era of ‘Patriotism.’” This was the first time that M. R. Neukirchen had been invited to address the National Conference of the prestigious American Association of Learned Societies. There would be hostile questions put to her at the conclusion of her talk, she supposed. At her own University where the faculty so supported her liberal position, yet there were dissenting voices from the right. But overwhelmingly her audience that evening would support her, she was sure.

It would be thrilling—to speak to this distinguished group, and to make an impression on them. Somehow it had happened, the shy schoolgirl had become, with the passage of not so many years, an impassioned and effective public speaker—a Valkyrie of a figure—fiercely articulate, intense. You could see that she cared so much—almost, at moments, M.R. quivered with feeling, as if about to stammer.

Audiences were transfixed by her, in the narrow and rarified academic world in which she dwelt.

I am baring my soul to you. I care so deeply!

Often she felt faint, beforehand. A turmoil in her stomach as if she might be physically ill.

The way an actor might feel, stepping into a magisterial role. The way an athlete might feel, on the cusp of a great triumph—or loss.

Her (secret) lover had once assured her It isn’t panic you feel, Meredith. It isn’t even fear. It’s excitement: anticipation.

Her (secret) lover was a brilliant but not entirely reliable man, an astronomer/cosmologist happiest in the depths of the Universe. Andre Litovik’s travels took him into extragalactic space far from M.R. yet he, too, was proud of her, and did love her in his way. So she wished to believe.

They saw each other infrequently. They did not even communicate often, for Andre was negligent about answering e-mail. Yet, they thought of each other continuously—or so M.R. wished to believe.

Possibly unwisely, given the dense underbrush here, M.R. was approaching the bridge from beneath. She’d been correct: the floor was planking—you could see sunlight through the cracks—as vehicles passed, the plank floor rattled. A pickup truck, several cars—the bridge was so narrow, traffic slowed to five miles an hour.

She’d learned to drive over such a bridge. Long ago.

She felt the old frisson of dread—a visceral unease she experienced now mainly when flying in turbulent weather—Return to your seats please, fasten your seat belts please, the captain has requested you return to your seats please.

At such times the terrible thought came to her: To die among strangers! To die in flaming wreckage.

Such curious, uncharacteristic thoughts M. R. Neukirchen hid from those who knew her intimately. But there was no one really, who knew M. R. Neukirchen intimately.

In a way it was strange to her, this curious fact: she had not (yet) died.

As the pre-Socratics pondered Why is there something and not rather nothing?—so M.R. pondered Why am I here, and not rather—nowhere?

A purely intellectual speculation, this was. M.R.’s professional philosophizing wasn’t tainted by the merely personal.

Yet, these questions were strange, and wonderful. Not an hour of her life when she did not give thanks.

M.R. had been an only child. An entire psychology has been devised involving the only child, a variant of the first-born.

The only child is not inevitably the first-born, however. The only child may be the survivor.

The only child is more likely to be gifted than a child with numerous siblings. Obviously, the only child is likely to be lonely.

Self-reliant, self-sufficient. “Creative.”

Did M.R. believe in such theories? Or did she believe, for this was closer to her personal experience, that personalities are distinct, individual and unique, and unfathomable—in terms of influences and causality, inexplicable?

She’d been trained as a philosopher, she had a Ph.D. in European philosophy from one of the great philosophy departments in the English-speaking world. Yet she’d taken graduate courses in cognitive psychology, neuroscience, international law. She’d participated in bioethics colloquia. She’d published a frequently anthologized essay titled “How Do You Know What You ‘Know’: Skepticism as Moral Imperative.” As the president of a distinguished research university in which theories of every sort were devised, debated, maintained, and defended—an abundance like a spring field blooming and buzzing with a profusion of life—M.R. wasn’t obliged to believe but she was obliged to take seriously, to respect.

My dream is to be—of service! I want to do good.

She was quite serious. She was wholly without irony.

The Convent Street bridge, in Carthage. Of course, that was the bridge she was trying to recall.

And other bridges, other waterways, streams—M.R. couldn’t quite recall.

In a kind of trance she was staring, smiling. As a child, she’d learned quickly. Of all human reflexes, the most valuable.

The river was a fast shallow stream on which boulders emerged like bleached bone. Fallen tree limbs lay in the water sunken and rotted and on these mud turtles basked in the October sun, motionless as creatures carved of stone. M.R. knew from her rural childhood that if you approached these turtles, even at a distance they would arouse themselves, waken and slip into the water; seemingly asleep, in reptilian stillness, they were yet highly alert, vigilant.

A memory came to her of boys who’d caught a mud turtle, shouting and flinging the poor creature down onto the rocks, dropping rocks on it, cracking its shell….

Why would you do such a thing? Why kill …?

It was a question no one asked. You would not ask. You would be ridiculed, if you asked.

She had failed to defend the poor turtle against the boys. She’d been too young—very young. The boys had been older. Always there were too many of them—the enemy.

These small failures, long ago. No one knew now. No one who knew her now. If she’d tried to tell them they would stare at her, uncomprehending. Are you serious? You can’t be serious.

Certainly she was serious: a serious woman. The first female president of the University.

Not that femaleness was an issue, it was not.

Without hesitation M.R. would claim, and in interviews would elaborate, that not once in her professional career, nor in her years as a student, had she been discriminated against, as a woman.

It was the truth, as M.R. knew it. She was not one to lodge complaints or to speak in disdain, hurt, or reproach.

What was that—something moving upstream? A child wading? But the air was too cold for wading and the figure too white: a snowy egret.

Beautiful long-legged bird searching for fish in the swift shallow water. M.R. watched it for several seconds—such stillness! Such patience.

At last, as if uneasy with M.R.’s presence, the egret seemed to shake itself, lifted its wide wings, and flew away.

Nearby but invisible were birds—jays, crows. Raucous cries of crows.

Quickly M.R. turned away. The harsh-clawing sound of a crow’s cry was disturbing to her.

“Oh!”—in her eagerness to leave this place she’d turned her ankle, or nearly.

She should not have stopped to walk here, Carlos was right to disapprove. Now her heels sank in the soft mucky earth. So clumsy!

As a young athlete M.R. had been quick on her feet for a girl of her height and (“Amazonian”) body-type but soon after her teens she’d begun to lose this reflexive speed, the hand-eye coordination an athlete takes for granted until it begins to abandon her.

“Ma’am? Let me help you.”

Ma’am. What a rebuke to her foolishness!

Carlos had approached to stand just a few feet away. M.R. didn’t want to think that her driver had been watching her, protectively, all along.

“I’m all right, Carlos, thank you. I think….”

But M.R. was limping, in pain. It was a quick stabbing pain she hoped would fade within a few minutes but she hadn’t much choice except to lean on Carlos’s arm as they made their way back to the car, along the faint path through the underbrush.

Her heart was beating rapidly, strangely. The birds’ cries—the crows’ cries—were both jeering and beautiful: strange wild cries of yearning, summons.

But what was this?—something stuck to the bottom of one of her shoes. The newly purchased Italian black-leather shoes she’d felt obliged to buy, several times more expensive than any other shoes M.R. had ever purchased.

And on her trouser cuffs—briars, burrs.

And what was in her hair?—she hoped it wasn’t bird droppings from the underside of that damned bridge.

“Excuse me, ma’am …”

“Thanks, Carlos! I’m fine.”

“Ma’am, wait …”

Gallant Carlos stooped to detach whatever it was stuck to M.R.’s shoe. M.R. had been trying to kick it free without exactly seeing it, and without allowing Carlos to see it; yet of course, Carlos had seen. How ridiculous this was! She was chagrined, embarrassed. The last thing she wanted was her uniformed Hispanic driver stooping at her feet but of course Carlos insisted upon doing just this, deftly he detached whatever had been stuck to the sole of her shoe and flicked it into the underbrush and when M.R. asked what it was he said quietly not meeting her eye:

“Nothing, ma’am. It’s gone.”

It was October 2002. In the U.S. capital, war was being readied.

If objects pass into the space “neglected” after brain damage, they disappear. If the right brain is injured, the deficit will manifest itself in the left visual field.

The paradox is: how do we know what we can’t know when it does not appear to us.

How do we know what we have failed to see because we have failed to see it, thus cannot know that we have failed to see it.

Unless—the shadow of what-is-not-seen can be seen by us.

A wide-winged shadow swiftly passing across the surface of Earth.

In the late night—her brain too excited for sleep—she’d been working on a philosophy paper—a problem in epistemology. How do we know what we cannot know: what are the perimeters of “knowing”…

As a university president she’d vowed she would keep up with her field—after this first, inaugural year as president she would resume teaching a graduate seminar in philosophy/ethics each semester. All problems of philosophy seemed to her essentially problems of epistemology. But of course these were problems in perception: neuropsychology.

The leap from a problem in epistemology/neuropsychology to politics—this was risky.

For had not Nietzsche observed—Madness in individuals is rare but in nations, common.

Yet she would make this leap, she thought—for this evening was her great opportunity. Her audience at the conference would be approximately fifteen hundred individuals—professors, scholars, archivists, research scientists, university and college administrators, journalists, editors of learned journals and university presses. A writer for the Chronicle of Higher Education was scheduled to interview M. R. Neukirchen the following morning, and a reporter for the New York Times Education Supplement was eager to meet with her. A shortened version of “The Role of the University in an Era of ‘Patriotism’” would be published as an Op-Ed piece in the New York Times. M. R. Neukirchen was a new president of an “historic” university that had not even admitted women until the 1970s and so boldly in her keynote address she would speak of the unspeakable: the cynical plot being contrived in the U.S. capital to authorize the president to employ “military force” against a Middle Eastern country demonized as an “enemy”—an “enemy of democracy.” She would find a way to speak of such things in her presentation—it would not be difficult—in addressing the issue of the Patriot Act, the need for vigilance against government surveillance, detention of “terrorist suspects”—the terrible example of Vietnam.

But this was too emotional—was it? Yet she could not speak coolly, she dared not speak ironically. In her radiant Valkyrie mode, irony was not possible.

She would call her lover in Cambridge, Massachusetts—to ask of him Should I? Dare I? Or is this a mistake?

For she had not made any mistakes, yet. She had not made any mistakes of significance, in her role as higher educator.

She should call him, or perhaps another friend—though it was difficult for M.R., to betray weaknesses to her friends who looked to her for—uplift, encouragement, good cheer, optimism….

She should not behave rashly, she should not give an impression of being political, partisan. Her original intention for the address was to consider John Dewey’s classic Democracy and Education in twenty-first-century terms.

She was an idealist. She could not take seriously any principle of moral behavior that was not a principle for all—universally. She could not believe that “relativism” was any sort of morality except the morality of expediency. But of course as an educator, she was sometimes obliged to be pragmatic: expedient.

Education floats upon the economy, and the goodwill of the people.

Even private institutions are hostages to the economy, and the good—enlightened—will of the people.

She would call her (secret) lover when she arrived at the conference center hotel. Just to ask What do you advise? Do you think I am risking too much?

Just to ask Do you love me? Do you even think of me? Do you remember me—when I am not with you?

It was M.R.’s practice to start a project early—in this case, months early—when she’d first been invited to give the keynote address at the conference, back in April—and to write, rewrite, revise and rewrite through a succession of drafts until her words were finely honed and shimmering—invincible as a shield. A twenty-minute presentation, brilliant in concision and emphasis, would be far more effective than a fifty-minute presentation. And it would be M.R.’s strategy, too, to end early—just slightly early. She would aim for eighteen minutes. To take her audience off guard, to end on a dramatic note …

Madness in individuals is rare but in nations, common.

Unless: this was too dire, too smugly “prophetic”? Unless: this would strike a wrong note?

“Carlos! Please put the radio on, will you? I think the dial is set—NPR.”

It was noon: news. But not good news.

In the backseat of the limousine M.R. listened. How credulous the media had become since the terrorist attacks of 9/11, how uncritical the reporting—it made her ill, it made her want to weep in frustration and anger, the callow voice of the defense secretary of the United States warning of weapons of mass destruction believed to be stored in readiness for attack by the Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein … Biological warfare, nuclear warfare, threat to U.S. democracy, global catastrophe.

“What do you think, Carlos? Is this ridiculous? ‘Fanning the flames’…”

“Don’t know, ma’am. It’s a bad thing.”

Guardedly Carlos replied. What Carlos felt in his heart, Carlos was not likely to reveal.

“I think you said—you served in Vietnam….”

Fanning the flames. Served in Vietnam. How clumsy her stock phrases, like ill-fitting prostheses.

It hadn’t been Carlos, but one of her assistants who’d mentioned to M.R. that Carlos had been in the Vietnam War and had “some sort of medal—‘Purple Heart’”—of which he never spoke. And reluctantly now Carlos responded:

“Ma’am, yes.”

In the rearview mirror she saw his forehead crease. He was a handsome man, or had been—olive-dark skin, a swath of silver hair at his forehead. His lips moved but all she could really hear was ma’am.

She was feeling edgy, agitated. They were nearing Ithaca—at last.

“I wish you wouldn’t call me ‘ma’am,’ Carlos! It makes me feel—like a spinster of a bygone era.”

She’d meant to change the subject and to change the tone of their exchange but the humor in her remark seemed to be lost as often, when she spoke to Carlos, and others on her staff, the good humor for which M. R. Neukirchen was known among her colleagues seemed to be lost and she drew blank expressions from them.

“Sorry, ma’am.”

Carlos stiffened, realizing what he’d said. Surely his face went hot with embarrassment.

Yet—she knew!—it wasn’t reasonable for M.R. to expect her driver to address her in some other way—as President Neukirchen for instance. If he did he stumbled over the awkward words—Pres’dent New-kirtch-n.

She’d asked Carlos to call her “M.R.”—as most of her University colleagues did—but he had not, ever. Nor had anyone on her staff. This was strange to her, disconcerting, for M.R. prided herself on her lack of pretension, her friendliness.

Her predecessor had insisted that everyone call him by his first name—“Leander.” He’d been an enormously popular president though not, in his final years, a very productive or even a very attentive president; like a grandfather clock winding down, M.R. had thought. He’d spent most of his time away from campus and among wealthy donors—as house guest, traveling companion, speaker to alumni groups. As a once-noted historian he’d seen his prize territory—Civil War and Reconstruction—so transformed by the inroads of feminist, African American studies, and Marxist scholarship as to be unrecognizable to him, and impossible for him to re-enter, like a door that has locked behind you, once you have stepped through. An individual of such absolute vanity, he wished to be perceived as totally without vanity—just a “common man.” Though Leander Huddle had accumulated a small fortune—reputedly, somewhere near ten million dollars—by way of his University salary and its perquisites and investments in his trustee-friends’ businesses.

M.R.’s presidency would be very different!

Of course, M.R. was not going to invest money in any businesses owned by trustees. M.R. was not going to accumulate a small fortune through her University connections. M.R. would establish a scholarship financed—(secretly)—by her own salary….

It will be change—radical change!—that works through me.

Neukirchen will be but the agent. Invisible!

She did have radical ideas for the University. She did want to reform its “historic” (i.e., Caucasian-patriarchal/hierarchical) structure and she did want to hire more women and minority faculty, and above all, she wanted to implement a new tuition/scholarship policy that would transform the student body within a few years. At the present time an uncomfortably high percentage of undergraduates were the sons and daughters of the most wealthy economic class, as well as University “legacies”—(that is, the children of alumni); there were scholarships for “poor” students, that constituted a small percentage; but the children of middle-income parents constituted a precarious 5 percent of admissions … M.R. intended to increase these, considerably.

For M. R. Neukirchen was herself the daughter of “middle-income” parents, who could never have afforded to send her to this Ivy League university.

Of course, M. R. Neukirchen would not appear radical, but rather sensible, pragmatic and timely.

She’d assembled an excellent team of assistants and aides. And an excellent staff. Immediately when she’d been named president, she’d begun recruiting the very best people she could; she’d kept on only a few key individuals on Leander’s staff.

At all public occasions, in all her public pronouncements, M. R. Neukirchen stressed that the presidency of the University was a “team effort”—publicly she thanked her team, and she thanked individuals. She was the most generous of presidents—she would take blame for mistakes but share credit for successes. (Of course, no mistakes of any consequence had yet been made since M.R. had taken over the office.) To all whom she met in her official capacity she appealed in her eager earnest somewhat breathless manner that masked her intelligence—as it masked her willfulness; sometimes, in an excess of feeling, this new president of the University was known to clasp hands in hers, that were unusually large strong warm hands.

It was the influence of her mother Agatha. As Agatha had also influenced M.R. to keep a cheerful heart, and keep busy.

As both Agatha and Konrad were likely to say, as Quakers—I hope.

For it was Quaker custom to say, not I think or I know or This is the way it must be but more provisionally, and more tenderly—I hope.

“Yes. I hope.”

In the front seat the radio voice was loud enough to obscure whatever it was M.R. had said. And Carlos was just slightly hard of hearing.

“You can turn off the radio, please, Carlos. Thanks.”

Since the incident at the bridge there was a palpable stiffness between them. No one has more of a sense of propriety than an older staffer, or a servant—one who has been in the employ of a predecessor, and can’t help but compare his present employer with this predecessor. And M.R. was only just acquiring a way of talking to subordinates that wasn’t formal yet wasn’t inappropriately informal; a way of giving orders that didn’t sound aggressive, coercive. Even the word Please felt coercive to her. When you said Please to those who, like Carlos, had no option but to obey, what were you really saying?

And she wondered was the driver thinking now It isn’t the same, driving for a woman. Not this woman.

She wondered was he thinking She is alone too much. You begin to behave strangely when you are alone too much—your brain never clicks off.

The desk clerk frowned into the computer.

“‘M. R. Neukirchen’”—the name sounded, on his lips, faintly improbable, comical—“yesss—we have your reservation, Mz. Neukirchen—for two nights. But I’m afraid—the suite isn’t quite ready. The maid is just finishing up….”

Even after the unscheduled stop, she’d arrived early!

She hadn’t even instructed Carlos to drive past her old residence Balch Hall—for which she felt a stab of nostalgia.

Not for the naïve girl she’d been as an undergraduate, nor even for the several quite nice roommates she’d had—(like herself, scholarship girls)—but for the thrilling experience of discovering, for the first time, the livingness of the intellectual enterprise, that had been, to her, the daughter of bookish parents, previously confined to books.

M.R. told the desk clerk that that was fine. She could wait. Of course. There was no problem.

“… no more than ten or fifteen minutes, Mz. Neukirchen. You can check in now, and wait in our library-lounge, and I will call you.”

“Thank you! This is ideal.”

Smile! Win more flies with honey than with vinegar Agatha would advise though this was not why, in fact, Agatha smiled so frequently, and so genuinely. And there was Konrad’s dry rebuttal, with a wink of the eye for their young impressionable daughter.

Sure thing! If it’s flies you want.

The library-lounge was an attractive wood-paneled room where M.R. could spread her things out on an oak table and continue to work.

Always it is a good thing: to arrive early.

The impulsive stop in the nameless little town by the nameless little creek or river hadn’t been a blunder after all—only just a curious episode in M.R.’s (private) life, to be forgotten.

Arrive early. Bring work.

She’d begun to acquire a reputation for being the most astonishing zealot of work.

It was known, M.R. was very bright—very earnest, idealistic—but it had not been quite known, how hard M.R. was willing to work.

For this brief trip, she’d brought along enough work for several days. And, of course, she would be in constant communication with Salvager Hall—the president’s team of aides, assistants, secretarial staff. In a constant stream e-mail messages came to her as president of the University, and these she dealt with both expeditiously and with an air of schoolgirl pleasure so it was known, and it would become more widely known, that M.R. never failed to include personal queries and remarks in her e-mail messages, she was irrepressibly friendly.

For we love our work. No more potent narcotic than work!

And M.R.’s administrative work was very different from her work as a writer/philosopher—administration is the skillful organizing of others, its center of gravity is exterior; all that matters, all that is significant, urgent—profound—is exterior.

“I want to be ‘of service.’ I do not want to be ‘served.’”

This too was a legacy of the Neukirchens. For the Quaker, the commonweal outweighs the merely personal.

Critically now M.R. was re-examining her address—“The Role of the University in an Era of ‘Patriotism’”—even as she found herself distracted by a memory of the bridge and the sharp water-smells—the mysterious faded lettering on the dark-brick building on the farther bank.

In the lobby, uplifted voices. Her fellow conferees were arriving.

She felt a stirring of apprehension, excitement. For soon, her anonymity would vanish.

The desk clerk had no idea who she was—(this was a relief!)—but others would know her, recognize her. This past year M. R. Neukirchen had become renowned in academic circles. She could not but think her elevation very unnerving, and very strange—accidental, really.

God has chosen you, dear Merry! God is a principle in the universe for good, and God has chosen you to implement His work.

In emotional moments her mother spoke like this—warmly, earnestly. It was something of a small shock to M.R. to realize that Agatha probably did believe in such a personal destiny for her daughter.

Another time M.R. leafed through the conference program—to check her name, to see if it was really there.

The program was a large glossy-white booklet with gilt letters on its cover: Fiftieth Annual National Conference of the American Association of Learned Societies. October 11–13, 2002. The conference was scheduled to begin with a 5:30 P.M. reception at which M.R. and other speakers were to be honored. Dinner was at 7 P.M. and at 8 P.M. the keynote speaker was listed—M. R. Neukirchen.

She’d given many talks, of course. Many lectures, speeches—presentations—but mostly in her academic field, philosophy. It was an honor for her to have been invited to speak to this organization, not the largest but the most distinguished of American intellectual/academic societies, for membership was limited and selective.

M.R. had herself been inducted into the organization young—not yet thirty, and an associate professor of philosophy at the University.

“Oh! Damn.”

She’d discovered mud on the cuffs of her trousers, and in the creases of her shoes. Irritably she brushed at the stains, that were still damp.

She touched her hair discovering something cobwebby-sticky in her hair, that must have sifted down from the wrought-iron bridge.

Fortunately, she’d brought other clothes to the conference. She would wash her face—check her hair—change quickly once she was given her room.

She had good clothes to wear, this evening. Since she’d become president of the University her female staffers had seen to it that M.R. looked “stylish”—her assistant Audrey Myles had insisted upon taking M.R. to New York City to shop and they’d come back with a chic Chanel-imitation Champagne-colored wool suit—with a skirt—by an American designer. And Audrey had convinced M.R. to buy handsome new shoes as well, with a one-inch heel—bringing M.R.’s height to a teetering five feet ten and a half inches.

At such a height, you could not hide. You had best imagine yourself as a prow on a ship—a brave Amazon girl-warrior with breastplates, spear uplifted in her right hand.

Her astronomer-lover, when he’d first sighted her on a street in Cambridge, Massachusetts, years before, had described her in his way. He’d claimed to have fallen in love with her, in this first sighting. And her hair in a tight-woven braid hanging down between her shoulder blades like a glittery bronze-brown snake.

Since she’d risen in administration at the University, M.R. had long since gotten rid of the girl-scholar braid. As she’d tried to rid herself of a naive sentimentality about the sort of love her astronomer-lover could provide her. Now her hair was cropped short, trimmed and styled by a New York City hairdresser, at Audrey’s insistence: it was dense, springy, no longer golden brown but the ambiguous hue of a winter-ravaged field threaded with metallic-gray hairs that glittered like filaments.

In official biographies, M. R. Neukirchen was forty-one years old in September 2002. And looking much younger.

As a little girl she’d seen her birth certificate. Her parents had shown her. A document stamped with the heraldic New York State gold seal stating her birth date, her name—her names.

Our secret you need to tell no one.

Our secret, God has blessed our family.

She was “Merry” then—“Meredith Ruth Neukirchen.” Her birthday was September 21. A very nice time of year, the Neukirchens believed: a prelude to the beautiful season of autumn. Which was why they’d chosen it for her.

Which was why she often forgot her birthday, and was surprised when others reminded her.

She hadn’t minded not being beautiful, as a girl in Carthage, New York. She’d learned to be objective about such matters. There were those who liked her well enough—who loved her, in a way—for her fierce wide smile that resembled a grimace of pain, and her stoicism in the face of actual pain or discomfort; she’d had to laugh seeing her picture in local papers, the expression of longing in her face that was so scrubbed-looking plain it might have been a boy’s face and not that of a young woman of eighteen:

MEREDITH RUTH NEUKIRCHEN, CLASS OF ’79 VALEDICTORIAN CARTHAGE HIGH SCHOOL.

It had been the kind of upstate New York, small-city school in which, as in a drain, the least-qualified and -inspired teachers wound up, bemused and stoical and resigned; there had been several teachers who’d seen in Meredith something promising, even exciting—but only one who had inspired her, though not to emulate him personally. And when poor Meredith—“Merry”—hadn’t even been asked to the senior prom, though she’d been not only valedictorian of her graduating class but also its vice president, one of the women teachers had consoled her—“You’ll just have to make your way somehow else, Meredith”—with fumbling directness though meaning to be kind.

Not as a woman, and not sexual.

Somehow else.

Soon after the senior prom to which M.R. had not been invited, M.R.’s prettiest girl-classmates were married, and pregnant; pregnant, and married. Some were soon divorced, and became “single mothers”—a very different domestic destiny from the one they’d envisioned for themselves.

Very few of M.R.’s classmates, female or male, went on to college. Very few achieved what one might call careers. Of her graduating class of 118 students very few left Carthage or Beechum County or the southern Adirondacks, where the economy had been severely depressed for decades.

One of those regions in America, M.R. had said, trying to describe her background to her astronomer-lover who traveled more frequently to Europe than to the rural interior of the United States, where poverty has become a natural resource: social workers, welfare workers, community-medical workers, public defenders, prison and psychiatric hospital staffers, family court officials—all thrived in such barren soil. Only fleetingly had M.R. considered returning, as an educator—once she’d left, she had scarcely looked back.

Don’t forget us, Meredith! Come visit, stay a while …

We love our Merry.

M.R. had pushed her laptop aside and was examining road maps, laid out on a table in the library-lounge for hotel guests.

Particularly M.R. was intrigued by a detailed map of Tompkins County. She hoped to determine where she’d asked Carlos to stop. South and west of Ithaca were small towns—Edensville, Burnt Ridge, Shedd—but none appeared to be the town M.R. was looking for. With her forefinger M.R. traced a thin curvy blue stream—this must be the river, or the creek—south of Ithaca; but there was only a tiny dot on that stream as of a settlement too minuscule to be named, or extinct.

“Why is this important? It is not important.”

She whispered aloud. She was puzzled by her disappointment.

Abruptly the map ended at the northern border of Tompkins County but there were maps of adjoining New York State counties; there was a road map of New York State that M.R. eagerly unfolded, with no hope that she could fold it neatly back up again. Some crucial genetic component was missing in M.R., she could never fold road maps neatly back up again once she unfolded them….

In the Neukirchen household, Konrad had been the one to carefully, painstakingly re-fold maps. Agatha had been totally incapable, vexed and anxious.

It feels like some kind of trick. It can’t be done!

M.R. saw: to the north and east of Tompkins County was Cortland County—beyond Cortland, Madison—then Herkimer, so curiously elongated among other, chunkier counties; beyond Herkimer, in the Adirondacks, the largest and least populated county in New York State, Beechum.

At the northwestern edge of Beechum County, the city of Carthage.

How many miles was it? How far could she drive, on a whim? It looked like less than two hundred miles, to the southernmost curve of the Black Snake River in Beechum County. Which computed to about three hours if she drove at sixty miles an hour. Of course, she wouldn’t have to drive as far as Carthage; she could simply drive, with no particular destination, see how far she got after two hours—then turn, and drive back.

How quickly her heart was beating!

M.R. calculated: it was just 1:08 P.M. She’d been waiting for her hotel room for nearly twenty minutes. Surely in another few minutes, the desk clerk would summon her, and she could check into the room?

The reception began at 5:30 P.M.—but no one would be on time. And then, at about 6 P.M., everyone would arrive at once, the room would be crammed with people, no one would notice if M.R. arrived late. Dinner was more essential of course since M.R. was seated at the speakers’ table—that wasn’t until 7 P.M. And of course, the keynote address at 8 P.M….

There was time—or was there? Her brain balked at calculations like a faulty machine.

“Absurd. No. Just stop.”

The spell was broken by the cell phone ringing at M.R.’s elbow. The first stirring notes of Mozart’s Eine Kleine Nachtmusik.

M.R. saw that the caller ID was UNIVERSITY—meaning the president’s office. Of course, they were waiting to hear from her there.

“Yes, I’ve arrived. Everything is fine. In a few minutes I’ll be checked in. And Carlos is on his way back home.”

It was a fact: Carlos had departed. M.R. had thanked him and dismissed him. Late in the afternoon of the third day of the conference Carlos would return, to drive M.R. back to the University.

Of course, M.R. had suggested that Carlos stay the night—this night—at the hotel—at the University’s expense—to avoid the strain of driving a second five-hour stretch in a single day. But Carlos politely demurred: Carlos didn’t seem to care much for this well-intentioned suggestion.

It was a relief Carlos had left, M.R. thought. The driver had lingered in the lobby for a while as if uncertain whether to leave his distinguished passenger before she’d actually been summoned to her hotel room; he’d insisted upon carrying her suitcase into the hotel for her—this lightweight roller-suitcase M.R. could handle for herself and in fact preferred to handle herself, for she rested her heavy handbag on it as she rolled it along; but Carlos couldn’t bear the possibility of being observed—by other drivers?—in the mildest dereliction of his duty.

“Ma’am? Should I wait with you?”

“Carlos, thank you! But no. Of course not.”

“But if you need …”

“Carlos, really! The hotel has my reservation, obviously. It will be just another few minutes, I’m sure.”

Still he’d hesitated. M.R. couldn’t determine if it was professional courtesy or whether this dignified gentleman in his early sixties was truly concerned for her—perhaps it was both; he told her please call him on her cell phone if she needed anything, he would return to Ithaca as quickly as possible. But finally he’d left.

M.R. thought Of course. His life is elsewhere. His life is not driving a car for me.

Questioned afterward Carlos Lopes would say I asked her if I should stay—her room wasn’t ready yet in the hotel—she said no, I should leave—she was working in a room off the lobby—I said maybe she would need me like if they didn’t have a room for her and I could drive her to some other hotel and she laughed and said no Carlos! That is very kind of you but no—of course there will be a room.

As the desk clerk would say Her room was ready for her at about 1:15 P.M. She was gracious about waiting, she said it was no trouble. But then a few minutes later she called the front desk—I spoke with her—she asked about a car rental recommendation. Sometime after that she must have left the hotel. Nobody would’ve seen her, the lobby was so crowded. Her room was empty at 8:30 P.M. when some people from the conference asked us to open it. There was no DO NOT DISTURB sign on the door. The lights were off. Her suitcase was on the bed opened but mostly unpacked and her laptop was on the bed, not opened. There weren’t any signs of anybody breaking into the room or anything disturbed and there was no note left behind.

By 2 P.M. she was in the rental car driving north of Ithaca.

Her lungs swelled with—relief? Exultation?

She’d told no one where she was going or even that she was going—somewhere.

Of course, M.R. was paying for the compact Toyota with her personal credit card.

Of course, M.R. knew that her behavior was impulsive but reasoned that since she’d arrived early at the conference, in fact hours before the conference officially began, this interlude—before 6 P.M., or 6:30 P.M.—was a sort of free fall, like gravity-less space.

Once she’d asked her (secret) lover how an astronomer can bear the silence and vastness of the sky which is unbroken/unending/unfathomable and which yields nothing remotely human in fact rather makes a mockery of human and he’d said—But darling! That is what draws the astronomer to his subject: silence, vastness.

Driving north to Beechum County she was driving into what felt like silence. For she’d left the radio off, and the wind whining and whistling at all the windows drained away all sound as in a vacuum leaving her brain blank.

Ancient time her lover called the sky without end predating every civilization on Earth that believed it was the be-all and end-all of Earth.

She’d resolved to drive for just an hour and a half in one direction. Three hours away would return her to the hotel by 5 P.M. and well in time to change and prepare for the reception.

Except the driving was wind-buffeted. She’d rented a small car.

Not so very practical for driving at a relatively high speed on the interstate flanked and overtaken by tractor-trailers.

In high school driver’s education class, M.R. had been an exemplary student. Aged sixteen she’d learned to parallel park with such skill, her teacher used her as a model for other students. Approvingly he’d said of her Meredith handles a car like a man.

Remembering how when she’d first begun driving she’d felt dizzy with excitement, happiness. That thrill of sheer power in the way the vehicle leaps when you press down on the gas pedal, turns when you turn the steering wheel, slows and stops when you brake.

Remembering how she’d thought This is something men know. A girl has to discover.

“‘Just to stretch my legs.’ No other reason.”

She laughed. Her laughter was hopeful. A thin dew of fever-dreams on her forehead, oily and prickling in her armpits. And some sort of snarl in her hair. As if in the night she’d been dreaming of—something like this.

She would have time to shower before the reception—wouldn’t she? Change into her chic presidential clothes.

As a girl—a big husky girl—a girl-athlete—M.R. had sweated like any boy, sweat-rivulets running down her sides, a torment at the nape of her neck beneath the bushy-springy hair. And in her crotch—a snaggle of even denser hair, exerting a sort of appalled fascination to the bearer—who was “Meredith”—in dread of this snaggle of hair being somehow known by others; as there were years—middle school, high school—of anxiety that her body would smell in such a way to be detected by others.

Of course, it had. Many times probably. For what could a husky girl do? Warm airless classroom-hours, sturdy thighs sticking/slapping together if you were not very careful.

As on certain days of the month, anxiety rose like the red column of mercury in a thermometer, in heat.

Having her period. Poor Meredith!

Everything shows in her face. Funny!

Early that morning before Carlos arrived—for M.R. had slept only intermittently through the night—she’d showered, of course, shampooed her hair. So long ago, seemed like another day.

And so another shower, back at the hotel. When she returned.

On the interstate M.R. was making good time in the compact little vehicle. Her speed held steady at just above sixty miles an hour which was a safe speed, even a cautious speed amid so many larger vehicles hurtling past her in the left lane as if with snorts of derision.

But—the beauty of this landscape! It required going away, and returning, to truly see it.

Farmland, hills. Wide swaths of farmland—cornfields, wheat—now harvested—rising in hills to the horizon. She caught her breath—those flame-flashes of sumac dark-red, fiery-orange by the roadside—amid darker evergreens, deciduous trees whose leaves hadn’t—yet—begun to die.

Already she was beyond Bone Plain Road, Frozen Ocean State Park. Passing signs for Boontown, Forestport, Poland and Cold Brook—names not yet familiar to her from her girlhood in Beechum County.

These precious hours! If her parents knew, they’d have wanted to see her—they’d have been willing to drive to Ithaca for the evening.

They’d have wanted to hear her keynote address. For they were so very proud of her. And they loved her. And saw so little of her since she’d left Carthage on that remarkable scholarship to Cornell, it must have perplexed them.

“I should have. Why didn’t I!”

It was as if M.R. had not thought of the possibility at all. As if a part of her brain had ceased functioning.

That peculiar sort of blindness/amnesia in which objects simply vanish as they pass into the area monitored by the damaged brain. Not that one forgets but that experience itself has been blocked.

Now that M.R. had assistants, it was no trouble to make such arrangements. At the hotel, for instance. Or, if the conference hotel was booked solid, at another local hotel. Audrey would have been delighted to book a room for M.R.’s parents.

M.R.’s lover had heard her speak in public several times. He’d been surprised—impressed—by her ease before a large audience, when M.R. was so frequently uneasy in his company.

Well, not uneasy—excited. M.R. was frequently so excited in his company.

She couldn’t bring herself to confess to her (secret) lover that intimacy with him was so precious to her, it was a strain to which she hadn’t yet become accustomed. She’d said with a smile No speaker makes eye contact with his audience. The larger the audience, the easier. That is the secret.

Her lover imagined her a far more composed and self-reliant individual than she was. It had long been a fiction of their relationship, that M.R. didn’t “need” a man in her life; she was of a newer, more liberated generation—for her lover was her senior by fourteen years, and often remarked upon this fact as if to absolve himself of any candidacy as the husband of a girl “so young.” Also, Andre was enmeshed in a painful marriage he liked to describe as resembling Laocoön and sons in the coils of the terrible sea-serpents.

M.R. laughed aloud. For Andre Litovik was so very funny, you might forget that his humor frequently masked a truth or a motive not-so-funny.

“Oh—God …”

Powerful air-suction from a passing/speeding trailer-truck made M.R.’s compact vehicle shudder. The trucker must have been driving at eighty miles an hour. M.R. braked her car, alarmed and frightened.

She’d been daydreaming, and not concentrating on her driving. She’d felt her mind drift.

Better to exit the interstate onto a state highway. This was safer, if slower. Through acres of steeply hilly farmland she drove into Cortland County, and she drove into Madison County, and she drove into Herkimer County and into the foothills of the Adirondacks and at last into Beechum County where mountain peaks covered in evergreens stretched hazy and sawtoothed to the horizon like receding and diminishing dreams.