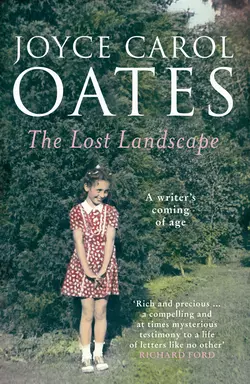

The Lost Landscape

Joyce Oates

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Биографии и мемуары

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 463.36 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: A momentous memoir of childhood and adolescence from one of our finest and most beloved writers, as we’ve never seen her before.In The Lost Landscape, Joyce Carol Oates vividly recreates the early years of her life in western New York state, powerfully evoking the romance of childhood and the way it colors everything that comes after. From early memories of her relatives to remembrances of a particularly poignant friendship with a red hen, from her first friendships to her first experiences with death, The Lost Landscape is an arresting account of the ways in which Oates’s life (and her life as a writer) was shaped by early childhood and how her later work was influenced by a hard-scrabble rural upbringing.In this exceptionally candid, moving, and richly reflective recounting of her early years, Oates explores the world through the eyes of her younger self and reveals her nascent experiences of wanting to tell stories about the world and the people she meets. If Alice in Wonderland was the book that changed a young Joyce forever and inspired her to look at life as offering endless adventures, she describes just as unforgettably the harsh lessons of growing up on a farm. With searing detail and an acutely perceptive eye, Oates renders her memories and emotions with exquisite precision to truly transport the reader to a bygone place and time, the lost landscape of the writer’s past but also to the lost landscapes of our own earliest, and most essential, lives.