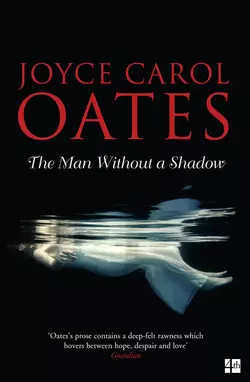

The Man Without a Shadow

Joyce Carol Oates

From bestselling author Joyce Carol Oates, a taut and fascinating novel that examines the mysteries of human memory and personalityIn 1965, a young research scientist named Margot Sharpe meets Elihu Hoopes, the subject of her study, a handsome amnesiac who cannot remember anything beyond the last seventy seconds. Over the course of thirty years, the two embark on mirroring journeys of self-discovery. Margot, enthralled by her charming, mysterious, and deeply lonely patient, as well as her officious supervisor, attempts to unlock Eli’s shuttered memories of a childhood trauma without losing her own sense of identity in the process. And Eli, haunted by memories of an unknown girl’s body underneath the surface of a lake, pushes to finally know himself once again, despite potentially devastating consequences. As Margot and Eli meet over and over again, Joyce Carol Oates’ tightly written, nearly clinical prose propels the lives of these two characters forwards, both suspended in a dream-like, shadowy present, and seemingly balanced on the thinnest, sharpest of lines between past and future. Made vivid by Oates’ eye for detail and searing insight into the human psyche, The Man Without a Shadow is an eerie, ambitious, and structurally complex novel, as poignant as it is thrilling.

Copyright (#ulink_385d2460-6b6d-5e2e-a119-ba546ec8ac76)

4th Estate

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.4thestate.co.uk (http://www.4thestate.co.uk)

This eBook first published in Great Britain by 4th Estate in 2016

First published in the United States by Ecco in 2016

Copyright © 2016 by The Ontario Review, Inc.

Cover photographs © Stephen Carroll / Trevillion Images

Joyce Carol Oates asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008165383

Ebook Edition © January 2016 ISBN: 9780008165406

Version: 2016-12-21

Dedication (#ulink_e55418b6-1bb7-59db-b5f7-5f512ca00d55)

TO MY HUSBAND CHARLIE GROSS,

MY FIRST READER

Epigraph (#ulink_c6b31766-6c1f-5caa-b64d-36c6341780c1)

The annihilation is not the terror.

The journey is the terror.

–ELIHU HOOPES

Contents

Cover (#u744033f3-9660-5711-851a-3a2990e28aa2)

Title Page (#u4fb1cad9-da14-537a-9814-21b2c8701194)

Copyright (#u72bdb94c-3e05-5467-bac0-3b2eec56d8a0)

Dedication (#u6db9954a-50c8-55d6-aa4d-bbaffe834a5f)

Epigraph (#u563d23d7-cf25-5da1-b49f-8222a5f274bf)

Chapter One (#u5a85b324-adf0-520e-a7d1-9b9ce234c0a9)

Chapter Two (#u9a205312-f20b-591c-85da-7f91d8e289c8)

Chapter Three (#u7c1e8132-5e76-55de-8a1f-4948dad79767)

Chapter Four (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Five (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Six (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Ten (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eleven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twelve (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgments (#litres_trial_promo)

Keep Reading … (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Novels by Joyce Carol Oates (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER ONE (#ulink_9507be46-f4bd-58cc-9f78-35b156c73a6d)

NOTES ON AMNESIA: PROJECT “E.H.” (1965–1996)

She meets him, she falls in love. He forgets her.

She meets him, she falls in love. He forgets her.

She meets him, she falls in love. He forgets her.

At last she says good-bye to him, thirty-one years after they’ve first met. On his deathbed, he has forgotten her.

HE IS STANDING on a plank bridge in a low-lying marshy place with his feet just slightly apart and firmly on his heels to brace himself against a sudden gust of wind.

He is standing on a plank bridge in this place that is new to him and wondrous in beauty. He knows he must brace himself, he grips the railing with both hands, tight.

In this place new to him and wondrous in beauty yet he is fearful of turning to see, in the shallow stream flowing beneath the bridge, behind his back, the drowned girl.

… naked, about eleven years old, a child. Eyes open and sightless, shimmering in water. Rippling-water, that makes it seem that the girl’s face is shuddering. Her slender white body, long white tremulous legs and bare feet. Splotches of sunshine, “water-skaters” magnified in shadow on the girl’s face.

SHE WILL CONFIDE in no one: “On his deathbed, he didn’t recognize me.”

She will confide in no one: “On his deathbed, he didn’t recognize me but he spoke eagerly to me as he’d always done, as if I were the one bringing him hope—‘Hel-lo?’”

BRAVELY AND VERY publicly she will acknowledge—He is my life. Without E.H., my life would have been to no purpose.

All that I have achieved as a scientist, the reason you have summoned me here to honor me this evening, is a consequence of E.H. in my life.

I am speaking the frankest truth as a scientist and as a woman.

She speaks passionately, yet haltingly. She seems to be catching at her breath, no longer reading from her prepared speech but staring out into the audience with moist eyes—blinded by lights, puzzled and blinking, she can’t see individual faces and so might imagine his face among them.

In his name, I accept this great honor. In memory of Elihu Hoopes.

At last to the vast relief of the audience the speech given by this year’s recipient of the Lifetime Achievement Award of the American Psychological Association has ended. Applause is quick and scattered through the large amphitheater like small flags flapping in a weak, wayward wind. And then, as the recipient turns from the podium, uncertain, confused—in belated sympathy the applause gathers and builds into a wave, very loud, thunderous.

She is startled. Almost for a moment she is frightened.

Are they mocking her? Do they—know?

Stepping blindly away from the podium she stumbles. She has left behind the heavy and unwieldy eighteen-inch cut-crystal trophy in the shape of a pyramid, engraved with her name. Quickly a young person comes to take the trophy for her, and to steady her.

“Professor Sharpe! Watch that step.”

“Hel-lo!”

Here is the first surprise: Elihu Hoopes greets Margot Sharpe with such eager warmth, it’s as if he has known her for years. As if there is a profound emotional attachment between them.

The second surprise: Elihu Hoopes himself, who is nothing like Margot Sharpe has expected.

It is 9:07 A.M., October 17, 1965. The single defining moment of Margot Sharpe’s life as it will be the single defining moment of Margot Sharpe’s career.

Purely coincidentally it is the eve of Margot Sharpe’s twenty-fourth birthday—(about which no one here in Darven Park, Pennsylvania, knows, for Margot has uprooted her midwestern life and cast it among strangers)—when she is introduced by Professor Milton Ferris to the amnesiac patient Elihu Hoopes as a student in Professor Ferris’s neuropsychology laboratory at the university. Margot is the youngest and most recent addition to the renowned “memory” laboratory; she has been accepted by Ferris as a first-year graduate student, out of numerous applicants, and she is dry-mouthed with anticipation. For weeks, she has been reading material pertinent to Project E.H.

Yet, the amnesiac E.H. is so friendly, and so gentlemanly, Margot feels comforted at once.

The man is unexpectedly tall—at least six feet two. He is straight-backed, vigorous. His skin exudes a warm glow and his eyes appear to be normal though Margot knows that the vision in his left eye is very poor. He is not at all the impaired individual Margot has expected to meet, who had to relearn a number of basic physical skills since the devastating injury to his brain just fifteen months before, when he was thirty-seven.

Margot thinks that E.H. emanates an air of manly charisma—that mysterious quality to which we respond instinctively without being able to explain. He is even well dressed, preppy-style, in clean khakis, a long-sleeved linen shirt, oxblood moccasins with patterned cotton socks—in contrast to other patients at the Institute whom Margot has glimpsed lolling about in hospital gowns or rumpled civilian wear. She has been told that E.H. is a descendant of an old, distinguished Philadelphia family named Hoopes, onetime Quakers who were central to the Underground Railway in the years preceding the Civil War; E.H. has a large, extended family in the area, but no wife, children, parents.

Elihu Hoopes is something of an artist, Margot has learned. He has sketchbooks, he keeps a journal. In his former lifetime he’d been a partner in a family-owned investment firm in Philadelphia but before that he’d been a student at Union Theological Seminary and a civil rights activist and supporter. Is it strange that Elihu Hoopes is unmarried, at nearly forty? Margot wonders if this somewhat patrician individual has had a history of relationships with women in which the women were found wanting, and cast aside—never guessing that his time for love, marriage, fathering children would come so abruptly to an end.

Camping alone on an island in Lake George, New York, the previous summer, E.H. was infected by a particularly virulent strain of herpes simplex encephalitis, that usually manifests itself as a cold sore on a lip, and fades within a few days; in E.H.’s case, the viral infection traveled along his optic nerve and into his brain, resulting in a prolonged high fever that ravaged his memory.

Unfortunately E.H. lingered too long before calling for help. Like a morbidly curious scientist he’d recorded his temperature in a notebook, in pencil—(the highest recorded reading was 103.1 degrees F)—before he’d collapsed.

This was ironic: a macho self-destructiveness. Like the premature death of the painter George Bellows who’d been reluctant to leave his studio to get help, though stricken by appendicitis.

In the vast Adirondack region there’d been no first-rate hospital, no adequate medical treatment for such a rare and catastrophic infection. By the time the delirious and convulsing man had been brought by ambulance to the Albany Medical Center Hospital where emergency surgery was performed to reduce the swelling in his brain it was already too late. Something essential had been destroyed in his brain, and the damage appears to be irreversible. (It is Milton Ferris’s hypothesis that the damaged region is the small seahorse-shaped structure called the hippocampus, located just above the brain stem and contiguous with the cerebral cortex, about which not much is yet known, but which seems to be essential for the consolidation and storage of memory.) And so, E.H. can form no new memories, and his memories of the past are erratic and uncertain; in clinical terms E.H. suffers from partial retrograde amnesia, and total anterograde amnesia. Though he continues to test high on standardized I.Q. tests, and despite his seemingly normal appearance and manner, E.H. is incapable of “remembering” new information for more than seventy seconds; often, it is less than seventy seconds.

Seventy seconds! A nightmare to contemplate.

The only consolation, Margot thinks, is that E.H. is a highly congenial person, and seems to thrive upon the attentions of strangers. The nature of his affliction at least precludes mental anguish—(so Margot thinks). His memories of the distant past are sometimes vividly detailed and oneiric; more recent memories (for approximately eighteen months preceding his illness) are likely to be cloudy and indistinct; both have been described as “mildly dissociative”—as if belonging to another person, not E.H. The subject is susceptible to moods, but a very limited range of moods; his affect has flattened, as a caricature is a flattened portrait of the complexity of human personality.

(Uncannily, E.H. will always recall events out of his past in the same way, using the same vocabulary; but he is never altogether certain if he is remembering correctly, even when external verification confirms that he is remembering correctly.)

Though E.H. doesn’t consistently remember certain of his relatives (whose faces are altering with time), he can identify the faces of famous people in photographs (if they predate his illness). At times, he demonstrates a remarkable, savant-like memory for recitations: statistics, historical dates, song lyrics, comic-strip characters and film dialogue (he is said to have memorized the entirety of the silent film Potemkin), passages from poems memorized in school (Whitman’s “When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom’d” is his favorite) and from revered American speeches (Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address, Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s The Only Thing We Have to Fear Is Fear Itself and Four Freedoms, Martin Luther King, Jr.’s I Have a Dream). He retains curiosity for “news”—watches TV news, each day reads at least two newspapers including the New York Times and the Philadelphia Inquirer—without the ability to remember any of it. Each day he completes the New York Times crossword puzzle as (his family has attested) he’d only occasionally taken time to complete the puzzle before his illness. (“Eli didn’t have that kind of time to waste.”)

Without seeming to think at all E.H. can recite multiplication tables, solve algebra problems without using a pencil, add up lengthy columns of numbers. It isn’t a surprise to learn that “Elihu Hoopes” had been a successful businessman in a highly competitive field.

Margot thinks that it is difficult to feel for this healthy-seeming man the visceral pity one might feel for a (visibly) handicapped person, for E.H.’s loss is far more subtle. In fact, though E.H. has been told repeatedly that he has a severe neurological deficit, it doesn’t seem that he quite understands that there is anything significant wrong with him—why he feels compelled to keep a notebook, for instance, as he’d begun to do after his illness.

Already Margot Sharpe has begun to keep a notebook herself. This will be a quasi-private document, primarily scientific, but partially a diary and journal, stimulated by her participation in Milton Ferris’s memory lab; through her career she will draw upon the material of the notebook, or rather notebooks, for her scientific papers and publications. “Notes on Amnesia: Project E.H.” will run into many notebooks to be eventually transcribed into a computer file to be continued to the very day of E.H.’s death (November 26, 1996) and beyond charting the fate of the amnesiac’s posthumous brain after it has been removed—very carefully!—from its skull.

But on this morning in October 1965 in the University Neurological Institute at Darven Park, Pennsylvania, all of Margot Sharpe’s life as a scientist lies before her. Introduced to “E.H.” she is dry-mouthed and tremulous as one who has been brought to the edge of a precipice to see a sight that dazzles her eyes.

Will my life begin, at last? My true life.

IN SCIENCE IT is understood that there are significant matters, and there are trivial matters.

So too in the matter of lives.

For it is a fact not generally, not publicly acknowledged: we have lives that are true lives, and we have lives that are accidental lives.

Perhaps it is rare that an individual discovers his true life at any age. Perhaps it is usually the case that an individual lives accidentally through an entire life. In terms of its consequence to what is called society or posterity, the accidental life is scarcely more than an addition of zeroes.

This is not to suggest that an accidental life is equivalent to a trivial life. Such lives may be enjoyable, and fulfilling: we all want to love and to be loved and within our families, and within a small circle of friends, we may feel ourselves cherished, thus exalted. But such lives pass away leaving the larger world untouched. There is scarcely a ripple, there is no shadow. There will be no memory of the merely accidental.

Margot Sharpe has come from a family of accidental lives. This family, in semi-rural north-central Ojibway County, Michigan, in a region of accidental lives. Yet already as a child of twelve she’d determined that she would not live so uncalculated a life as the lives of those who surrounded her and her way of discovering her true life would be through leaving her hometown Orion Falls, and her family, as soon as that was possible.

In Orion Falls young people may go away—to enlist in the armed forces, to branches of the state university, to nursing school, and so forth; but they all return. Margot Sharpe knows that she will not return.

Margot has always been curious, highly inquisitive. Her first, favorite book was the illustrated Darwin for Beginners which she’d discovered on a library shelf, aged eleven. Here was a book with a magical story—“evolution.” Another favorite book of her childhood was Marie Curie: A Woman in Physics. In high school she’d happened to read an article on B. F. Skinner and “behaviorism” that had intrigued and excited her. She has always asked questions for which there are not ready answers. To be a scientist, Margot thinks, is to know which questions to ask.

From the great Darwin she learned that the visible world is an accumulation of facts, conditions: results. To understand the world you must reverse course, to discover the processes by which these results come into being.

By reversing the course of time (so to speak) you acquire mastery over time (so to speak). You learn that “laws” of nature are not mysteries but knowable as the exits on Interstate 75 traversing the State of Michigan north and south.

Is it unjust, ironic?—that catastrophe in one life (the ruin of E.H.) precipitates hope and anticipation in others (Milton Ferris’s “memory” lab)? The possibility of career advancement, success?

It is the way of science, Margot thinks. A scientist searches for her subject as a predator searches for her prey.

At least, no one had introduced the encephalitis virus into Elihu Hoopes’s brain with the intention of studying its terrible consequences, as Nazi doctors might have done; or performed radical psychosurgery on him for some presumably beneficial purpose. Chimps and dogs, cats and rats have been so experimented upon, in great numbers, and for a while in the 1940s and 1950s there’d been a vogue of prefrontal lobotomies on hapless human beings, with frequently catastrophic (if not very accurately recorded) results.

Sometimes the radical changes caused by lobotomies were perceived, by the families of the patients at least, to be “beneficial.” A rebellious adolescent becomes abruptly tractable. A sexually adventurous adolescent (usually female) becomes passive, pliant, asexual. An individual prone to outbursts of temper and obstinacy becomes childlike, docile. “Beneficial” for family and for society is not always so for the individual.

In the case of Elihu Hoopes it seems likely that a personality change of a radical sort had been precipitated by his illness, for no adult male of E.H.’s achievement and stature would be so trusting and childlike, so touchingly and naively hopeful. You have the uneasy feeling, in E.H.’s presence, that here is a man desperate to sell himself—to be liked. The change in E.H. is allegedly so extreme that his fiancée broke off their engagement within a few months of his illness, and E.H.’s family, relatives, friends visit him ever less frequently. He lives in the affluent Philadelphia suburb Gladwyne with an aunt, the younger sister of his (deceased) father, herself a “rich” widow.

From personal experience Margot knows that it is far easier to accept a person ravaged by physical illness than one ravaged by memory loss. Far easier to continue to love the one than the other.

Even Margot who’d loved her “great-grannie” so much as a little girl had balked at being taken to visit the elderly woman in a nursing home. This is not something of which Margot is particularly proud, and so she has begun a process of forgetting.

But E.H. is very different from her elderly relative suffering from (it would be diagnosed after her death) Alzheimer’s. If you didn’t know the condition of E.H. you would not immediately guess the severity of his neural deficit.

Margot wonders: Was E.H.’s encephalitis caused by a mosquito bite? Was it a particular species of mosquito? Or—is it a common mosquito, itself infected? In what other ways is herpes simplex encephalitis transmitted? Have there been other instances of such infections in the Lake George, New York, region? In the Adirondacks? She supposes that research scientists in the Albany area are investigating the case.

“How horrible! The poor man …”

It is the first thing you say, regarding E.H. When you are safely out of his earshot.

Or rather, it is the first thing Margot Sharpe says. Her lab colleagues are more adjusted to E.H. for they have been working with him for some time.

Nervously Margot smiles at the stricken man, who does not behave as if he understands that he is stricken. She smiles at him, which inspires him to smile at her, with a flash of something like familiarity. (She thinks: He isn’t sure if he should know me. He is looking for cues from me. I must not send him misleading cues.)

Margot is new to such a situation. She has never been in the presence of a living “subject.” She can’t help but feel pity for E.H., and horror at his predicament: how abruptly Elihu Hoopes was transformed from being an attractive, vigorous, healthy man in the prime of life to a man near death, losing more than twenty pounds, white blood count plummeting, extreme anemia, delirium. A herpes simplex infection resulting in encephalitis is so rare, E.H. might more readily have been struck by lightning.

Yet E.H.’s manner isn’t at all guarded, wary, or stiff; he might be a host welcoming guests to his home, whose names he doesn’t quite recall. Indeed he seems at home in the Institute setting—at least, he doesn’t seem disoriented. For these sessions at the Institute E.H. is brought from his aunt’s suburban home near Philadelphia by an attendant, in a private car; originally E.H. was a patient at the Institute, and then an outpatient; he is still under the medical care of Institute staff. Though E.H. recognizes no one, yet it is flattering to him, how so many people recognize him.

He seems to have little capacity for brooding, as he has lost his capacity for self-reflection. Margot is touched by the way he pronounces her name—“Mar-go”—as if it were a beautiful and unique name and not a harsh spondee that has always somewhat embarrassed her.

Though Milton Ferris hasn’t intended for the introduction of his youngest lab member to be anything more than a fleeting pro forma gesture, E.H. takes pleasure in drawing out the ritual. He shakes her hand in a way both courtly and caressing. And unmistakably he leans close to Margot as if inhaling her.

“Welcome—‘Margot Sharpe.’ You are a—new doctor?”

“No, Mr. Hoopes. I’m a graduate student in Professor Ferris’s lab.”

Quickly E.H. amends: “‘Graduate student—Professor Ferris’s lab.’ Yes. I knew that.”

In an enthusiastic voice E.H. repeats Margot’s words precisely, as if they were a riddle to be decoded.

Individuals who are memory-challenged can contend with the handicap by repeating facts or strings of words—“rehearsing.” But Margot wonders if E.H.’s repetitions carry with them comprehension, or only rote mimicry.

To the brain-damaged man, much in ordinary life must be fraught with mystery at all times—where is he? What is this place? Who are the people who surround him? Beyond these perplexities is the larger, greater mystery of his very existence, his survival after near-death, which is (Margot supposes) too profound for him to consider. The amnesiac with a very limited short-term memory is like one who stands so close to a mirror that his face is virtually pressed against it—he cannot “see” himself.

Margot wonders what E.H. sees, looking into a mirror. Is his face a surprise to him, each time? Whose face?

It is touching, too—(though this might be attributable to the man’s neurological deficit and not his gentlemanly nature)—that, in his attitude toward his visitors, E.H. makes no distinction between the least consequential person in the room (Margot Sharpe) and the most consequential (Milton Ferris); he has lost his instinctive capacity for ranking. It isn’t clear what he makes of Ferris’s other assistants, or rather “associates” (as Ferris would call them: de facto they are “assistants”) whom he has met before: another, older female graduate student, several postdoctoral fellows, and an allegedly brilliant young assistant professor who is Ferris’s protégé at the Institute and has published several important papers with him in neuroscience journals.

E.H. is slow to surrender Margot Sharpe’s hand. He continues to stand close beside Margot as if surreptitiously sniffing her hair, her body. Margot is uneasy, for she doesn’t want to annoy Milton Ferris; she knows that her supervisor is waiting for an opportunity to initiate the morning’s testing, which will require several hours in the Institute testing-room, even as E.H. in his concentration upon the young, black-haired, attractive woman seems to have forgotten the reason for his guests’ visit.

(It occurs to Margot to wonder if a brain-damaged person might be likely to compensate for memory loss with a heightened olfactory sense? A plausible and exciting possibility which she might one day explore, Margot thinks.)

(The amnesiac subject is clearly far more interested in Margot than in the others—she hopes that his interest isn’t just frankly sexual. It occurs to her to wonder if the subject’s sexuality has been affected by his amnesia, and in what way …)

But E.H. speaks to her in a kindly manner, as if she were a young girl.

“‘Mar-go.’ I think you were in my grade school class at Gladwyne Day—‘Mar-go Madden’—unless it was ‘Margaret Madden’ …”

“I’m afraid not, Mr. Hoopes.”

“No? Really? Are you sure? This would have been in the late 1930s. In Mrs. Scharlatt’s sixth-grade class you sat at the front, far left by the window. You had silver barrettes in your hair. Margie Madden.”

Margot feels her face heat. It is just not the flirtation that makes her uneasy but a kind of complicity of hers, as of the others who are listening, in their reluctance to tell E.H. frankly of his condition.

It would be Dr. Ferris’s obligation to tell him this; or rather, to tell him again. (For E.H. has been told many times.)

“I—I’m afraid not …”

“Well! Will you call me ‘Eli’? Please.”

“‘Eli.’”

“Thank you! That’s very kind.”

E.H. consults a little notebook he keeps in a pocket of his khakis, and jots down a note. He holds the notebook at a slight, subtle angle so that no one can see what he is writing; yet not so emphatically an angle that the gesture is insulting to Margot.

Margot has been told that the amnesiac has been keeping notebooks since he’d recovered from his illness and was strong enough to hold a pen in his hand. So far he has accumulated many dozens of these small notebooks as well as sketchbooks measuring forty-eight inches by thirty-six inches; he never arrives at the Institute without both of these. Apparently the notebook and the sketchbook serve different functions. In the notebooks E.H. jots down stray facts, names, times and dates; he inserts columns torn from magazines and newspapers from the fourth-floor lounge. (Male staffers who use the fourth-floor men’s restroom report finding such detritus there each day that E.H. is on the premises—that is how they know, they say, that “your fancy amnesiac” has been there.) The sketchbooks are for drawings.

The complex neurological skills needed for reading, writing, and mathematical calculation seem not to have been much affected by E.H.’s illness, as they were acquired before the infection. So E.H. reads brightly from the notebook: “‘Elihu Hoopes attended Amherst College and graduated summa cum laude with a double major in economics and mathematics … Elihu Hoopes has attended Union Theological Seminary and has a degree from the Wharton School of Business.’” E.H. reads this statement as if he has been asked to identify himself. Seeing his visitors’ carefully neutral expressions he regards them with a little tic of a smile as if, for just this moment, he understands the folly and pathos of his predicament, and is begging their indulgence. Forgive me! The amnesiac has learned to gauge the mood of his visitors, eager to engage and entertain them: “I know this. I know who I am. But it seems reasonable to check one’s identity frequently, to see if it is still there.” E.H. laughs as he snaps the little notebook shut and slips it back into his pocket, and the others laugh with him.

Only Margot can barely bring herself to laugh. It seems to her cruel somehow.

There is laughter, and there is laughter. Not all laughter is equal.

Laughter too depends upon memory—a memory of previous laughter.

Dr. Ferris has told his young associates that their subject “E.H.” will possibly be one of the most famous amnesiacs in the history of neuroscience; potentially he is another Phineas Gage, but in an era of advanced neuropsychological experimentation. In fact E.H. is far more interesting neurologically than Gage whose memory had not been severely affected by his famous head injury—the penetration of his left frontal lobe by an iron rod.

Dr. Ferris has cautioned them against too freely discussing E.H. outside their laboratory, at least initially; they should be aware of their “enormous good fortune” in being part of this research team.

Though she is only a first-year graduate student Margot Sharpe doesn’t have to be told that she is fortunate. Nor does Margot Sharpe need to be told not to discuss this remarkable amnesiac case with anyone. She does not intend to disappoint Milton Ferris.

Ferris and his assistants are preparing batteries of tests for E.H., of a kind that have never before been administered. The subject is to remain pseudonymous—“E.H.” will be his identity both inside and outside the Institute; and all who work with him at the Institute and care for him are pledged to confidentiality. The Hoopes family, which has donated millions of dollars to the University of Pennsylvania’s School of Medicine, has given permission exclusively to the University Neurological Institute at Darven Park for such testing so long as E.H. is willing and cooperative—as indeed, he appears to be. Margot doesn’t like to think that a kicked dog, yearning for human approval and love, desperate for a connection with the “normal,” could not be more eagerly cooperative than the dignified Elihu Hoopes, son of a wealthy and socially prominent Philadelphia family.

Elihu Hoopes is trapped in a perpetual present, Margot thinks. Like a man wandering in circles in a twilit woods—a man without a shadow.

And so he is thrilled to be saved from such a twilight and made the center of attention even if he doesn’t know quite why. How otherwise does the amnesiac know that he exists? Alone, without the stimulation of attentive strangers asking him questions, even the twilight would fade, and he would be utterly lost.

“‘MARGO NOT-MADDEN’?—THAT is your name?”

At first Margot can’t comprehend this. Then, she sees that E.H. is attempting a sort of joke. He has taken out his little notebook again, and has painstakingly inscribed in it what appears to be a diagram in logic. One category, represented by a circle, is M M and a second category, also represented by a circle, is M Not-M. Between the two circles, which might also be balloons, since strings dangle from them, is a broken line.

“My days of mastering symbolic logic seem to have abandoned me,” E.H. says pleasantly, “but I think the situation is something like this.”

“Oh—yes …”

How readily one humors the impaired. Margot will come to see how, within the amnesiac’s orbit, as within the orbit of the blind or the deaf, there is a powerful sort of pull, depending upon the strength of will of the afflicted.

Still, Margot is uncertain how to respond. It is a feeble and somehow gallant attempt at humor but she doesn’t want to encourage the amnesiac subject in prevarication—she knows, without needing to be told, that her older colleagues, and Milton Ferris, will disapprove.

Also, an awkward social situation has evolved which involves caste: the (subordinate) Margot Sharpe has supplanted, in E.H.’s limited field of attention, the (predominant) Milton Ferris. It is even possible that the brain-damaged man (deliberately, craftily) has contrived to “neglect” Dr. Ferris who stands just at his elbow waiting to interrupt—(“neglect” is a neurological term referring to a pathological blindness caused by brain damage); and so it is imperative that Margot ease away from E.H. so that Ferris can reassert himself as the (obvious) person in authority. Margot hopes to execute this maneuver as inconspicuously as possible without either the impaired man or the distinguished neuropsychologist seeing what she is doing.

Margot doesn’t want to hurt E.H.’s feelings, even if his feelings are fleeting, and Margot doesn’t want to offend Milton Ferris, the most distinguished neuroscientist of his generation, for her scientific career depends upon this fiercely white-bearded individual in his late fifties about whom she has heard “conflicting” things. (Milton Ferris is the most brilliant of brilliant scientists at the Institute but Milton Ferris is also an individual whom “you don’t want to cross in any way, even inadvertently. Especially inadvertently.”) As a young woman scientist, one of very few in the Psychology Department at the University, Margot knows instinctively to efface herself in such circumstances; as an undergraduate at the University of Michigan with a particular interest in experimental cognitive psychology, she absorbed such wisdom through her pores.

Also, it was abundantly clear: there were virtually no women professors in the Psychology Department, and none at all in Neuroscience at U-M.

Margot is not a beautiful young woman, she is sure. She has a distrust of conventional “beauty”—her more attractive girl-classmates in school were distracted by the attention of boys, in several cases their lives altered (young love, early pregnancies, hasty marriages). But Margot considers herself a canny young woman, and she is determined not to make mistakes out of naïveté. If E.H. is a kind of dog in his eagerness to please, Margot is not unlike a dog rescued from a shelter by a magnanimous master—one who must be assured, at all times, in the most subtle ways possible, that he is indeed master.

In his steely jovial way Milton Ferris is explaining to E.H. that Margot is “too young” to have been a classmate of his in the late 1930s—“This young woman from Michigan is new to the university and new to our team at the Institute where she will be assisting us in our ‘memory project.’”

E.H. frowns thoughtfully as if he is absorbing the information packed into this sentence. Affably he concurs: “‘Michigan.’ Yes—that makes it unlikely that we were classmates at Gladwyne.”

In the same way E.H. is trying to behave as if the term “memory project” is familiar to him. (Margot wonders if this persuasive and congenial persona has been a nonconscious acquisition in the amnesiac. She wonders whether testing has been done in the acquisition of such “memory” by individuals as brain-damaged as E.H.)

As Milton Ferris speaks expansively of “testing,” E.H. exhibits eagerness and enthusiasm. Over the course of the past eighteen months he has been tested countless times by neurologists and psychologists but it isn’t likely that he can remember individual sessions or tests. From before his injury he retains a general knowledge of what a “test” is—he knows what an “I.Q. test” is. From before his injury he might know that his I.Q. was once tested at 153, when he was eighteen years old; but he can’t know that, after his injury, his I.Q. has been tested several times, and has been measured in the range of 149 to 157. Still of superior intelligence, at least theoretically.

This is fascinating to Margot: E.H.’s pre-injury vocabulary, language skills, and mathematical abilities have survived more or less intact but (it is said) he can’t retain new words, concepts, or facts even if they are embedded in familiar information. He has been observed taking notes on the financial section of his favorite newspapers but when asked about what he has been inscribing a few minutes later he shrugs disdainfully—“Homo sapiens is the species that ‘makes’ and ‘loses’ money. What else is new?” He has forgotten what had so engrossed him but he can readily invent a substitute with which to disguise his memory loss.

At times E.H. seems to know that John F. Kennedy was assassinated recently—(two years ago)—while at other times E.H. speaks of “President Kennedy” as if the man were still alive—“Kennedy will need to revise his position on Cuba. He will need to lead the country out of the quagmire of Vietnam.”

And, grandiloquently: “Some of us are hoping to get to Washington, to meet with the president. The situation is getting more and more urgent.”

It would seem delusional except, as Ferris has noted, the Hoopes family of Philadelphia has long had ties with state and federal politicians.

Like many brain-afflicted individuals E.H. carries with him dictionaries and other word-books; he keeps long lists of words in his notebooks alphabetically arranged—that is, there are pages of A’s, B’s, C’s, and so forth. (E.H. takes pleasure in consulting these when he does the Times crossword puzzle as, his family has attested, he’d never consulted a dictionary when doing the puzzle before his illness.) His proficiency in math is impressive. His knowledge of world geography is impressive. He can discuss rival economic theories—Keynesian, classical, Marxist; he likes to expound upon von Neumann’s Theory of Games and Economic Behavior, key lines of which he has memorized. But if questioned he can only repeat more or less what he has already said; his ideas are fixed, like his vocabulary. No new ideas or revisions of the past can penetrate. And if he is challenged his affable nature vanishes and he becomes irritable, ironic. He is adept at board games and puzzles of a kind he’d mastered when he was a boy but he can’t easily learn new games.

Margot supposes that if E.H. could reason more clearly he would assume that the repeated tests he undergoes constitute a kind of treatment or therapy that might allay his condition; but he can’t know his “condition” though it has been explained to him repeatedly; and he can’t know that the tests are in fact “repeated” or that they are for the sake of experimental research—that’s to say for the sake of neuroscience and not for the sake of the subject.

Ferris is speaking carefully to E.H.: “Mr. Hoopes—Eli—let me explain again that I am a neuropsychologist who teaches at the University of Pennsylvania and these are members of my lab. We’ve been working with you for the past fifteen weeks here at the Institute at Darven Park, each Wednesday, and we have made some exciting preliminary discoveries. You have met me before, and we have gotten along splendidly! I am ‘Milton Ferris’—”

E.H. nods vehemently, even a little impatiently, as if he knows all this: “‘Mil-ton Fer-ris’—yes. ‘Dr. Ferris.’”

“I am not a ‘doctor’—I am a professor. I have a Ph.D. of course but that is not essential! Please just call me—”

“‘Professor Fer-ris.’ Yes.”

“And I have explained—I am not a clinician.”

This is a way of telling the subject I am not a medical doctor. You are not my patient.

But E.H. seems to purposefully misunderstand, awkwardly joking: “Well, Professor—that makes two of us. I am not a clinician, either.”

E.H. has spoken a little too loudly. Is this a way of signaling irritation with Professor Ferris? Since his attention has been forcibly removed from black-haired Margot Sharpe?

(Margot wonders too if E.H. is speaking quickly as if to signal, subliminally, that he isn’t much interested in the information that Milton Ferris is providing him; despite his severe amnesia E.H. “remembers” enough from previous exchanges to know that he won’t remember this information, either, thus resents being given it.)

While his visitors look on E.H. leafs through his little notebook until he comes to a crucial page. He smiles, showing the page to Margot rather than to Ferris—a drawing of two tennis players, one of them wildly flailing with his racket as a ball sails over his head. (Is this player meant to be E.H.? The player’s hair and features suggest that this is so. And the other player, with a blurred face and exaggerated grin, is meant to be—Death?)

“This—‘tennis’—I used to play. Pretty damned good on the Amherst team. Are we going to play ‘tennis’ now?”

“Eli, you’re an excellent tennis player. You can play tennis another day. But right now, if you’d like to take a seat, and …”

“‘Excellent’? Is that so? But I have not played tennis in a long time, I think.”

“In fact, Eli, you played tennis just last week.”

Eli stares at Ferris. This is not what Eli has expected to hear and he seems incapable of absorbing it but without missing a beat Ferris says in a warm and uplifting voice, “Now, Eli, you’ve always trounced me. And it has been reported to me not only that you’d played with one of the best players on the staff but you’d won each game.”

“‘Reported’—really!”

E.H. laughs, faintly incredulous.

Margot sees: the poor man is feeling the unease of one being made to understand that the most complete knowledge of himself can come only from the outside—from strangers.

A melancholy conviction, Margot thinks, to realize that you can’t know yourself as reliably as strangers can know you!

Patiently Milton Ferris explains to E.H. why he has been brought to the Institute that morning, and why Ferris and his laboratory are going to be “testing” him—as they’d done in the past; E.H. listens politely at first, then becomes bemused and beguiled by Margot whom he has rediscovered: she is wearing a black wraparound skirt with black tights beneath, a black jersey pullover that fits her petite frame tightly, and black ballerina flats—the clothes of a schoolgirl dancer and not the crisp white lab coats of the medical staff or the dull-green uniforms of the nursing staff. There is no laminated ID on her lapel to inform him of her name.

Annoyed, Ferris says: “Whenever you’d like to begin, Mr. Hoopes—Eli. That’s why we’re here.”

“Why you are here, Doctor. But why am I here?”

“You’ve enjoyed our tests in the past, Eli, and I think you will again.”

“That’s why I am here—to ‘enjoy’ myself?”

“We are hoping to establish some facts concerning memory. We are hoping to explore the question of whether memory is ‘global’ in the brain—not localized; or whether it is localized. And you have been helping us, Eli.”

“Have they kicked me out of the office?—has someone taken my place? My brother Averill, and my uncle—” E.H. pauses as if, for a vexed moment, he can’t recall the name of one of his Hoopes relatives, an executive at Hoopes & Associates, Inc.; then he rallies, with one of his enigmatic remarks: “Where else would I be, if I could be somewhere else?”

Milton Ferris assures E.H. that he is in “just the right place, at just the right time to make history.”

“Did I tell you? I’ve heard Reverend King speak. Several times. That is ‘history.’”

“Yes. An extraordinary man, Reverend King …”

“He spoke in Philadelphia on the steps of the Free Library, and he spoke in Birmingham, Alabama, at a Negro church that was subsequently burnt to the ground by white racists. He is a very brave man, a saint. He is a saint of courage. I intend to march with him again when my condition improves—as I’ve been promised.”

“Of course, Eli. Maybe we can help arrange that.”

“It’s because I was clubbed on the head—billy clubbed—in Alabama. Did I show you? The scar, where my hair doesn’t grow …”

E.H. lowers his head, flattens his thick dark hair to show them a faint zigzag line in his scalp. Margot feels an impulse to reach out and touch it—to stroke the poor man’s head.

She understands—It’s loneliness he feels most.

“Yes, you did show us your scar, Eli. You’re a very lucky man to have escaped with your life.”

“Am I! You think that’s what I managed, Doctor—to ‘escape with my life.’” E.H. laughs sadly.

Milton Ferris continues to speak with E.H., humoring him even as he soothes him. Margot can imagine Ferris calming an excited laboratory animal, a monkey for instance, as it is about to be “sacrificed.”

For such is the euphemism in experimental science. The lab animals are not killed, certainly not murdered: they are sacrificed.

Shortly, in E.H.’s presence, you come to see that the amnesiac’s smiling is less childlike and eager than desperate, and piteous. His is the eagerness of a drowning person hoping to be rescued by someone, anyone, with no idea what rescue might be, or from what.

In me he sees—something. A hope of rescue.

In profound neural impairments there may yet be isolated islands of memory that emerge unpredictably; Margot wonders if her face, her voice, her very scent might trigger dim memories in E.H.’s ruin of a brain, so that he feels an emotion for her that is as inexplicable to him as it might be to anyone else. Even as he tries to listen to Dr. Ferris’s crisp speech he is looking longingly at Margot.

Margot has seen laboratory animals rendered helpless, though still living and sensate, after the surgical removal of parts of their brains. And she has read everything she could get her hands on, about amnesia in human beings. Still it is unnerving for her to witness such a condition firsthand, in a man who might pass, at a little distance, as normal-seeming—indeed, charismatic.

“Very good, Eli! Would you like to sit down at this table?”

E.H. smiles wryly. Clearly, he doesn’t want to sit down; he is most at ease on his feet, so that he can move freely about the room. Margot can imagine this able-bodied man on the tennis court, fluid in motion, not wanting to be fixed in place and so at a disadvantage.

“Here. At this table, please. Just take a seat …”

“‘Take a seat’—where take it?” E.H. smiles and winks. He makes a gesture as if about to lift a chair; his fingers flutter and flex. Ferris laughs extravagantly.

“I’d meant to suggest that you might sit in a chair. This chair.”

E.H. sighs. He has hoped to humor this stranger with the fiercely white short-trimmed beard and winking eyeglasses who speaks to him so familiarly.

“Heil yes—I mean, hell yes—Doctor!”

E.H.’s smile is so affable, he can’t have meant any insult.

As they prepare to begin the morning’s initial test E.H.’s attention is drawn away from Margot who plays no role at all except as observer. And Margot has eased into the periphery of the subject’s vision where probably he can’t see her except as a wraith. She assumes that he has forgotten the names of others in the room to whom he’d been introduced—Kaplan, Meltzer, Rubin, Schultz. It is a relief to her not to be competing with Milton Ferris for the amnesiac’s precarious attention.

After his illness E.H.’s performance on memory tests showed severe short-term loss. Asked by his testers to remember strings of digits, he wavered between five and seven. Now, months later, he can recall and recite nine numbers in succession, when required; sometimes, ten or eleven. Such a performance is within the normal range and one would think that E.H. is “normal”—his manner is calm, methodical, even rather robotic; then as complications are introduced, as lists become longer, and there are interruptions, E.H. becomes quickly confused.

The experiment becomes excruciating when lists of digits are interrupted by increasing intervals of silence, during which the subject is required to “remember”—not to allow the digits to slip out of consciousness. Margot imagines that she can feel the poor man straining not to lose hold—the effort of “rehearsing.” She would like to clasp his hand, to comfort and encourage him. I will help you. You will improve. This will not be your entire life!

Impairment is the great leveler, Margot thinks. Eighteen months ago, before his illness, Elihu Hoopes would scarcely have glanced twice at Margot Sharpe. She is moved to feel protective toward him, even pitying, and she senses that he would be grateful for her touch.

Forty intense minutes, then a break of ten minutes before tests continue at an ever-increasing pace. E.H. is eager and hopeful and cooperative but as the tests become more complicated, and accelerated, E.H. is thrown into confusion ever more quickly (though he tries, with extraordinary valor, to maintain his affable “gentlemanly” manner). As intervals grow longer, he seems to be flailing about like a drowning man. His short-term memory is terribly reduced—as short as forty seconds.

After two hours of tests Ferris declares a longer break. The examiners are as exhausted as the amnesiac subject.

E.H. is given a glass of orange juice, which is his favorite drink. He hasn’t been aware until now that he’s thirsty—he drinks the juice in several swallows.

It is Margot Sharpe who brings E.H. the orange juice. This female role of nurturer-server is deeply satisfying to her for E.H. smiles with particular warmth at her.

She feels a mild sensation of vertigo. Surely, the amnesiac subject is perceiving her.

Restless, exhausted without knowing (recalling) why, E.H. stands at a window and stares outside. Is he trying to determine where he is? Is he trying to determine who these strangers are, “testing” him? He is a proud man, he will not ask questions.

Like an athlete too long restrained in a cramped space or like a rebellious teenager E.H. begins to circle the room. This behavior is just short of annoying—perhaps it is indeed annoying. E.H. ignores the strangers in the room. E.H. flexes his fingers, shakes his arms. He stretches the tendons in his calves. He reaches for the ceiling—stretching his vertebrae. He mutters to himself—(is he cursing?)—yet his expression remains affable.

“Mr. Hoopes? Would you like your sketchbook?”—one of the Institute staff asks, handing the book to him.

E.H. is pleased to see the sketchbook. E.H. is (perhaps) surprised to see the sketchbook. He pages through it frowning, holding the book in such a way to prevent anyone else seeing its contents.

Then, he discovers his little notebook in a shirt pocket. This he opens eagerly, and peruses. He records something in the notebook, and slips it back into his pocket. He looks into the sketchbook again, discovers something he doesn’t like and tears it out, and crumples it in his hand. Margot is fascinated by the amnesiac’s behavior: Is it coherent, to him? Is there a purpose to it? She wonders if, before his illness, he’d kept a little notebook like this one, and carried an oversized sketchbook around with him; possibly he had. And so the effort of remembering these now is not unusual.

If he believes himself alone, with no one close to observe him, E.H. ceases smiling. He’s frowning and somber like one engrossed in the heart-straining effort of trying to figure things out.

Margot thinks how sad, how exhausting, the amnesiac can’t remember that he has been involved in this effort for any sustained period of time. He might have been in this place for a few minutes, or a few hours. He seems to know that he doesn’t live here, but he has no clear idea that he is living with a relative in Gladwyne and not by himself in Philadelphia as he’d been at the time of his illness.

No matter how many times a test involving rote memory is repeated, E.H. never improves. No matter how many times E.H. is given instructions, he has to be given the instructions yet another time.

The amnesiac’s brain resembles a colander through which water sifts continually, and never accumulates; those years before his illness, which constitute most of the man’s life of thirty-eight years, resemble a still, distant water glimpsed through dense foliage as in a hallucinatory landscape by Cézanne.

Margot wonders if there can be some residual, unfathomable memory in the part of E.H.’s brain that has been damaged? Whether, at the periphery of the damage, in adjoining tissue, some sort of neurogenesis, or brain repair, might take place? And could such neurogenesis be stimulated?

So relatively little is known of the human brain, after so many millennia! The brain is the only organ whose functions must be theorized from observed behavior, and whose basic physiology is scarcely comprehended at the present time—that is, 1965. Only animal brains can be examined “live”—primarily monkey brains. Invasive exploration of the (living, normal) human brain is forbidden. Margot wonders: Are complex memories distributed throughout the cerebral cortex, or localized?—and if localized, how? From what is known of E.H.’s brain, the hippocampus and adjacent tissue had been devastated by the viral infection—but have other parts of the brain remained unimpaired? Unless E.H. undergoes brain surgery, Margot thinks, or sophisticated scanning machines are developed to “X-ray” the brain, it isn’t likely that the precise anatomy of E.H.’s brain will be known until after his death when the brain can be autopsied.

In that instant Margot feels a glimmer of horror, and excitement. She sees E.H. on a marble slab in a morgue: a corpse, skull sawed open. The pathologist will remove the brain that will be fixed, sectioned, stained, examined and analyzed by the neuroscientist.

She will be the neuroscientist.

E.H. glances worriedly at her as if he can read her thoughts. Margot feels her face burn like one who has dared to touch another intimately, and has been detected.

But I will be your friend, Mr. Hoopes!—Eli.

I will be the one you can trust.

“Unlocking the mystery of memory”—Margot Sharpe will be among the first.

With an uplifted forefinger, to retain Margot’s attention, E.H. leafs through his little notebook in search of something significant. In his bright affable voice he reads:

“‘There is no journey, and there is no path. There is no wisdom, there is emptiness. There is no emptiness.’” He pauses to add, “This is the wisdom of the Buddha. But there is no wisdom, and there is no Buddha.” He laughs, with inexplicable good humor.

His examiners stare at him, unable to join in.

TESTING RESUMES. E.H. appears eager again, hopeful.

It is hard to comprehend: to the subject, the morning’s adventure is only now beginning. He has forgotten that he is “tired.”

Like appetite, “tiredness” depends much upon memory. Margot would not have believed this could be so—it seems unnatural!

A scientist soon learns: much in Nature is “unnatural.”

At this midpoint Milton Ferris departs. He has an appointment—a luncheon perhaps. The principal investigator entrusts his assistants to run the tests he has designed without his supervision.

Margot follows instructions diligently: even when she knows what to do next she waits for Alvin Kaplan, Ferris’s protégé, to instruct her. Testing E.H. is laborious, repetitive, yet fascinating—memory tests of various kinds, auditory and visual, of gradually increasing complexity.

One of the tests seems purposefully designed to frustrate and discourage the subject. E.H. is instructed by Kaplan to count “as high as you can without stopping.” E.H. begins counting and continues for an impressively long time, beyond seventy seconds; his counting is methodical, by rote. Then, at numeral eighty-nine, Kaplan interrupts, distracting E.H. by showing him a card with an elaborate geometrical design E.H. is asked to describe—“Looks like three pyramids upside down or maybe—pineapples?”

And now when Kaplan asks E.H. to continue with his counting, E.H. is utterly baffled. He has no idea how to proceed.

“‘Counting’—what? What was I ‘counting’?”

“You were counting numbers ‘as high as you can’—then you stopped to describe this card. But now, Eli, you can continue.”

“‘Continue’—what?”

“You don’t remember the count?”

“‘Count’—? No. I don’t remember.”

E.H. stares at the illustrated card that has distracted him, registering now that it is a trick.

“I played cards when I was a little boy. I played checkers and chess, too.” E.H. glances about as if looking for more cards, or game boards.

E.H.’s fingers twitch. His usually affable eyes glare with fury. How he would like to tear into bits the stupid card with a picture of pyramids, or pineapples!

Seeing the look in E.H.’s face Margot feels a twinge of guilt. She wonders if the test isn’t cruel after all—mental cruelty. Though E.H. has clearly enjoyed being the epicenter of attention until now.

Margot thinks—But he won’t remember! He will forget.

She thinks of those laboratory animals of decades past whose vocal cords were sometimes cut—monkeys, dogs, cats. So that their cries of pain and terror could not be expressed; their torturers were spared hearing, and did not need to register their suffering. Before a new and more humane era of animal experimentation but well within the memory of Milton Ferris, she is sure.

Ferris has often joked of the new “humane” era—its restrictions on animal research, the zealotry of “animal terrorists” protesting experiments of the kind he’d done himself not long ago with splendid results.

Margot does not like to speculate how she would have behaved in such laboratories, in the past. Would she have protested the suffering of animals? Or would she have silently, shamefully concurred?—for to have objected would have been tantamount to being expelled from the great man’s lab, and from a career in neuroscience itself.

Margot tells herself it is all science: a quest for the truth that is elusive, deep-lying.

For truth is not lying on the surface of the earth, scattered bits of fossil you might fit together like a jigsaw puzzle. Truth is buried, hidden, labyrinthine. What others see is likely to be surface—superficial. The scientist is one who delves deeper.

E.H. is looking blankly about the examining room, which has become an unknown place to him. It’s as if a stage set has been dismantled and all that remains are barren walls. The bright eager smile has faded from his lips. Elihu Hoopes is a marooned man who has suffered a grievous loss; his manner exudes, not charisma, but desperation. “You were at eighty-nine, Mr. Hoopes,” Margot says gently, to comfort the forlorn man. “You were doing very well when you were interrupted.” She ignores the stares of Kaplan and the others which are an indication to her that she has misspoken.

Hearing Margot’s soft but insistent voice behind him E.H. turns to her in surprise. He has been focusing his attention upon Kaplan and he has totally forgotten Margot—he registers surprise that there are several others in the room, and Margot behind him, sitting in a corner like a schoolgirl, observing and taking notes.

“Hel-lo!—hel-lo!”

It is clear that E.H. has never seen Margot Sharpe before: she is a diminutive young woman with unusually pale skin, black eyebrows and lashes, glossy black bangs hiding much of her forehead; her almond-shaped eyes would be beautiful if not so narrowed in thought.

She is eccentrically dressed in black, layers of black like a dancer. Notebook on her lap, pen in hand, frowning, yet smiling, she is—very likely—a young doctor? medical student? (Not a nurse. He knows that she is not a nurse.) Yet, she isn’t wearing a white lab coat. There is no ID on her lapel which vexes and intrigues E.H.

Ignoring Kaplan and the others E.H. extends his hand to shake the young woman’s hand. “Hel-lo! I think we know each other—we went to school together—did we? In Gladwyne?”

The black-haired young woman hesitates. Then gracefully rises from her seat and comes to him, to slip her hand into his, with a smile.

“Hello, Mr. Hoopes—‘Eli.’ I am Margot Sharpe—whom you have never met before today.”

ACROSS THE GIRL’S white face beneath the rippling water are shadows of dragonflies and “skaters.” It is strange to see, the shadows of the insects are larger than the living insects

He has discovered her, in the stream. No one else knows—he is alone in this place.

But he doesn’t look, he has not (yet) seen the drowned girl. He was not there, so he cannot see. He cannot remember what he has not seen.

On the plank bridge in this strange place so many years later he does not turn his head. He does not glance around. He grips the railing tight in both his hands, bravely he steels himself against the anticipated wind.

CHAPTER TWO (#ulink_d8dc2a29-616b-53ba-9fef-5a3c05a1001a)

Mr. Hoopes? Eli?”

“Hel-lo!”

“My name is Margot Sharpe. I’m Professor Ferris’s associate. We’ve met before. We’ve come to take up a little of your time this morning …”

“Yes! Wel-come.”

Light coming up in his eyes. That leap of hope in his eyes.

“Wel-come, Margot!”

Her hand gripped in his, a clasp of recognition.

He does remember me. Not consciously—but he remembers.

She can’t write about this, yet. She has no scientific proof, yet.

The amnesiac will discover ways of “remembering.” It is a non-declarative memory, it bypasses the conscious mind altogether.

For there is emotional memory, as there is declarative memory.

There is a memory deep-embedded in the body—a memory generated by passion.

Suffused with happiness, Margot Sharpe feels like a balloon rapidly, giddily filling with helium.

“MR. HOOPES? ELI?”

“Hel-lo! Hel-lo.”

He has not ever seen her before. Eagerly he smiles at her, leans close to her, to shake her hand.

In his large, strong hand, Margot Sharpe’s small hand.

“You may not recall, we’ve met before—‘Margot Sharpe.’ I’m one of Professor Ferris’s research associates. We’ve been working together for—well, some time.”

“‘Mar-got Sharpe.’ Yes. We’ve been working together for—some time.” E.H. smiles gallantly as if he knows very well how long they’ve been working together, but it is a secret between them.

Today E.H. has the larger of his sketchbooks with him. He has finished the New York Times crossword puzzle—the newspaper page is discarded as usual, on the floor.

E.H. has been sketching with a stick of charcoal, seated beside a window in the anterior of the fourth-floor testing-room. He appears to be oblivious of the plate glass window that is dramatically lashed with rain, as he is oblivious of his clinical surroundings; the objects of E.H.’s art, which excite his fierce attention, are almost exclusively interior, and he does not care to share them with others.

(Except sometimes, Margot Sharpe.)

(Though Margot knows not to ask E.H. to see his drawings but to wait for E.H. to offer to show her. The offer, if it comes, will come spontaneously.)

“Do you have any idea how long we’ve been working together, Eli?”—Margot always asks.

E.H.’s smile wavers. He speaks thoughtfully, gravely.

“Well—I think—maybe—six weeks.”

“Six weeks?”

“Maybe more, or maybe less. You know, I have some problem with what is called ‘memory.’”

“How long have you had this problem, Eli?”

“How long have I had this problem? Well—I think—maybe—six weeks.” E.H. smiles at Margot, with a pleading expression. He is still gripping Margot’s hand; gently, she has to detach it.

“Do you know what has caused this problem, Eli?”

“Well, it’s ‘neurological.’ I suppose they’ve done X-rays. I think I remember my head shaved. My skull was fractured in Birmingham, Alabama—no one knew at the time. A ‘hairline’ fracture. But then, at the lake back in July, a few months ago, there was a fire. I think that’s what they told me—a fire. Hard to believe that I was careless leaving burning embers in the fireplace but—something happened.” E.H. pauses, frowning like one who is struggling to pull up, from the depths of a well, something unwieldy, very heavy that is straining every muscle in his body. “A fire, that burnt up my damned brain.”

“A fever, maybe?”

“A fever is a fire. In the damned brain.”

It is a wet windy overcast morning in March 1969.

SHE THINKS, HIS name has been eerily prescient—Hoopes.

For Elihu Hoopes has lived, for the past four and a half years, in an indefinable present-tense. A kind of time-hoop, a Möbius strip that turns upon itself, to infinity.

Except “infinity” is less than seventy seconds.

There is no was in Elihu Hoopes’s life, there is only is.

Forever he will be thirty-seven years old. Forever, he will be confused about where he is, and what has happened to him.

A fire? I think it was a fire. Or, Granddaddy’s two-passenger single-prop plane crash-landed on the island, and burst into flames. And later in the hospital, I think there was a fire, too. My clothes and hair were wet, but smoldering. I could smell my hair singed. I may have breathed in some of the fire, and burnt my lungs.

They said that I had a high fever but—it was a fire, I could see and smell.

The girl was not found. There were rescue parties searching for her. In the woods around Lake George. On the islands.

If someone had taken her, it was believed he might’ve taken her to one of the islands. If he had a boat. If no one saw.

In his little, light Beechcraft aircraft painted bright chrome yellow like a giant bird Granddaddy flew above the lake. Many times Granddaddy flew above the lake, you would hear the prop-plane engine passing low over the roof of the house.

Granddaddy said, Come with me, Eli! We will search together for your lost cousin.

Not the first time the little boy had flown in the plane with his grandfather but it would be the last.

IN HIS BRIGHT affable voice E.H. begins to read from his notebook.

“‘There is no journey, and there is no path. There is no wisdom, there is emptiness. There is no emptiness.’”

Pausing to add, “This is the wisdom of the Buddha. But there is no wisdom, and there is no Buddha.”

He laughs, sadly.

“There is no test, and there is no ‘testes.’”

And he laughs again. Sadly.

SHE HAS BEEN instructed: to discover, you have to destroy.

To locate the source of behavior in the brain, you have to destroy much of the brain.

Monkey-, cat-and rat-brains. In search of elusive and mysterious memory. Years, decades, thousands of animal-brains, hundreds of thousands of hours of surgery. Systematically, methodically. Meticulous lab records. Unyielding cruelty of the research scientist to whom no (living) specimen is an end in itself but a (possible) means to a greater end. Hundreds of thousands of animals sacrificed in the pursuit of the “engram”—the brain’s ostensible record of memory.

A principle of experimental neuroscience.

No one can surgically explore a (living, normal) human brain, only just animal-brains. And all these decades, results have been inconclusive. Margot Sharpe notes in her amnesia logbook the (famous/infamous) conclusion of the great experimental psychologist Karl Lashley:

This series of experiments has yielded a good bit of information about what and where the memory trace is not. I sometimes feel … the necessary conclusion is that (memory) is just not possible.

THE CHASTE DAUGHTER. How lucky Margot Sharpe has been! And she wants to think—My career—my life—lies all before me.

By 1969 the phenomenon of the amnesiac “E.H.” is beginning to be known in scientific circles.

An extraordinary case of total anterograde amnesia! And the subject otherwise in good health, intelligent, cooperative, sane—a rarity in brain pathology research where living patients are likely to be psychotic, moribund, or brain-rotted alcoholics.

Articles by Milton Ferris of the University Neurological Institute at Darven Park on “E.H.” have begun to appear in the most prestigious neuroscience journals; usually these articles list Ferris’s research associates as co-authors, and Margot Sharpe is among them. Seeing her name in print, in such company, has been deeply gratifying to Margot, and it has happened with surprising swiftness.

Rich with data, graphs, statistics, and citations, the articles bear such titles as “Losses in Recent Memory Following Infectious Encephalitis”—“Retention of ‘Declarative’ and ‘Non-declarative’ Memory in Amnesia: A History of ‘E.H.’”—“Short-Term Retention of Verbal, Visual, Auditory and Olfactory Items in Amnesia”—“Encoding, Storing, and Retrieval of Information in Anterograde Amnesia.” Their preparation is a lengthy, collaborative effort of months, or even years, with Milton Ferris overseeing the process. No paper can be submitted to any journal, of course, without Ferris’s imprimatur, no matter who has actually designed and executed the experiments, and who has done most of the research and writing. Recently, Margot has been given permission by Ferris to design experiments of her own involving sensory modality, and the possibility of “non-declarative” learning and memory. In the prestigious Journal of American Experimental Psychology a paper will soon appear with just the names of Milton Ferris and Margot Sharpe as authors; this is a forty-page extract from Margot’s dissertation titled “Short-Term and Consolidated Memory in Retrograde and Anterograde Amnesia: A Brief History of ‘E.H.’” It is, Milton Ferris has told Margot, the most ambitious and thoroughly researched paper of its kind he has ever received from a female graduate student—“Or any female colleague, for that matter.”

(Ferris’s praise is sincere. No irony is intended. It is 1969—it is not an age of gender irony in scientific circles, where few women, and virtually no feminists, have penetrated. To her shame, Margot has been thrilled to hear Milton Ferris spread the word of her to his colleagues, who’ve made a show of being impressed. Margot doesn’t want to think that her mentor’s praise is somewhat mitigated by the fact that there are only two women professors in the Psychology Department at the university, both “social psychologists” whom the experimental psychologists and neuroscientists treat with barely concealed scorn.)

That the lengthy article has been accepted so relatively quickly after Margot submitted it to the Journal of American Experimental Psychology must have something to do with Ferris’s intervention, Margot thinks. It has not escaped her notice that one of the editors of the journal is a protégé of Ferris of the late 1940s; Ferris himself is listed among numerous names on the masthead, as an “advisory editor.”

In any case, she has thanked Ferris.

She has thanked Ferris more than once.

Margot is conscious of her very, very good luck. Margot is anxious to sustain this luck.

It isn’t enough to be brilliant, if you are a woman. You must be demonstrably more brilliant than your male rivals—your “brilliance” is your masculine attribute. And so, to balance this, you must be suitably feminine—which isn’t to say emotionally unstable, volatile, “soft” in any way, only just quiet, watchful, quick to absorb information, nonoppositional, self-effacing.

Margot thinks—It is not difficult to be self-effacing, if you have a face at which no one looks.

“HEL-LO!”

“Hello, Mr. Hoopes—‘Eli.’ How are you?”

“Very good, thanks. How are you?”

In the vicinity of E.H. you feel the gravitational tug of the present tense.

In the vicinity of E.H., you glance about anxiously for your own shadow, as if you might have lost it.

Margot is very lonely except—Margot is not lonely when she is with E.H. Others in Ferris’s lab would be astonished to learn that Margot Sharpe who is so stiffly quiet in their presence speaks impulsively at times to the amnesiac subject E.H.; she has confided in him, as to a close and trusted friend, when they are alone together and no one else can hear.

She has volunteered to take E.H. for walks in the parkland behind the Institute. She has volunteered to take E.H. downstairs to the first-floor cafeteria, for lunch. If E.H. is scheduled for medical tests she volunteers to take him.

She is cheerful in E.H.’s company, as E.H. is cheerful in hers. She has boasted to E.H. of her academic successes, as one might boast to an older relative, a father perhaps. (Though Margot doesn’t think of Elihu Hoopes as fatherly: she is too much attracted to him as a man.) She has admitted to him that she is, at times, very lonely here in eastern Pennsylvania, where she knows no one—“Except you, Eli. You are my only friend.” E.H. smiles at this revelation as if their exchange was a part of a test and he is expected to speak on cue: “Yes—‘my only friend.’ You are, too.”

Margot knows that E.H. lives with an aunt, and assumes that he must see family members from time to time. She knows that his engagement was broken off a few months after E.H.’s recovery from surgery, and that his fiancée never visits him. What of his other friends? Have they all abandoned him? Has E.H. abandoned them? The impaired subject will wish to retreat, to avoid situations that exacerbate stress and anxiety; E.H. is safest and most secure at the Institute perhaps, where he can’t fail to be, almost continuously, the center of attention.

Margot thinks how for the amnesiac subject, are not all exchanges part of a test? Is not life itself a vast, continuous test?

It isn’t clear during their intimate exchanges if E.H. remembers Margot’s name—(frequently, he confuses her with his childhood classmate)—but unmistakably, he remembers her.

He understands that she is a person of some authority: a “doctor” or a “scientist.” He respects her, and relates to her in a way he doesn’t relate to the nursing staff, so far as Margot has observed.

Of course, you can say anything to E.H. He will be certain to forget it within seventy seconds.

And how difficult this is to comprehend, even for the “scientist”: what Margot has confided in E.H. is inextricably part of her memory of him, but it is not part of his memory of her.

Margot confides in E.H.: her imagination is so aflame she has trouble sleeping through the night. She wakes every two or three hours, excited and anxious. New ideas! New ideas for tests! New theories about the human brain!

She tells E.H. how badly she wants to please Milton Ferris; how fearful she is of disappointing the man—(who is frequently disappointed with young colleagues and associates, and has a reputation for running through them, and dismissing them); she wants to think that Ferris’s assessment of her “brain for science” is accurate, and not exaggerated. It’s her fear that Ferris has made her one of his protégées because she is a young woman of extreme docility and subservience to him.

Margot confesses to E.H. how sometimes she falls into bed without removing her clothing—“Without showering. Sleeping in my own smell.”

(So that E.H. is moved to say, “But your smell is very nice, my dear!”)

She confesses how exhausted she makes herself working late at the lab as if in some way unknown to her she disapproves of and dislikes herself—can’t bear herself except as a vessel of work; for she will not be loved if she doesn’t excel, and there is no way for her to excel except by working and pleasing her elders, like Milton Ferris. She recalls from a literature class at the University of Michigan a nightmarish short story in which the body of a condemned man is tattooed with the law he’d broken, which he is supposed to “read”—she doesn’t recall the author’s name but has never forgotten the story.

E.H. says, with an air of affectionate rebuke, “No one forgets Franz Kafka’s ‘In the Penal Colony.’”

He too had read it as an undergraduate—at Amherst.

Margot is surprised, and touched. “You remember it, Eli? That’s—of course, that’s …” It is utterly normal and natural for E.H. to remember a story he’d read years before his illness. Yet, Margot who’d read the story not nearly so long ago, could not recall the title.

E.H. begins to recite: “‘“It’s a peculiar apparatus,” said the Officer to the Traveler, gazing with a certain admiration at the device … It appeared that the Traveler had responded to the invitation of the Commandant only out of politeness, when he’d been invited to witness the execution of a soldier condemned to death for disobeying and insulting his superior … Guilt is always beyond doubt.’”

E.H. laughs, strangely. Margot has no idea why.

Something about the man without a shadow reciting these lines makes her fearful—I don’t want to know. Oh please!—I don’t want to know.

THEY HAVE NEVER told him—Your cousin is dead. Your cousin was dead as soon as she disappeared.

No one saw. No one knows.

Wake up, Eli! Silly Eli, it’s only a dream.

So much Eli has seen that summer, only a dream.