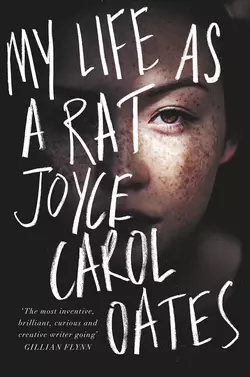

My Life as a Rat

Joyce Carol Oates

A brilliant and thought-provoking novel about family, loyalty and betrayalOnce I’d been Daddy’s favourite. Before something terrible happened.Violet Rue is the baby of the seven Kerrigan children and adores her big brothers. What’s more, she knows that a family protects its own. To go outside the family – to betray the family – is unforgiveable. So when she overhears a conversation not meant for her ears and discovers that her brothers have committed a heinous crime, she is torn between her loyalty to her family and her sense of justice. The decision she takes will change her life for ever.Exploring racism, misogyny, community, family, loyalty, sexuality and identity, this is a dark story with a tense and propulsive atmosphere – Joyce Carol Oates at her very best.

Copyright (#ulink_3b62c035-84fe-5922-be2c-527049cd6c79)

4th Estate

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.4thEstate.co.uk (http://www.4thEstate.co.uk)

This eBook first published in Great Britain by 4th Estate in 2019

Copyright © The Ontario Review, Inc. 2019

Cover photograph © Getty Images

Joyce Carol Oates asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Information on previously published material appears here (#litres_trial_promo).

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins

Source ISBN: 9780008339647

Ebook Edition © April 2019 ISBN: 9780008339661

Version: 2019-05-04

Dedication (#ulink_3b62c035-84fe-5922-be2c-527049cd6c79)

To my friend Elaine Showalter,

and to my husband and first reader, Charlie Gross

Contents

Cover (#ufdaef3bc-d7c7-5e60-a59c-da121ac1fde4)

Title page (#uc3810183-088c-573d-b7b8-684d935bc3e6)

Copyright (#u65144f6b-c23d-515a-99b7-d8861990d610)

Dedication (#ub7022a1a-1fc0-5c7d-9fda-a54dfa91f77f)

I (#ufd451ee4-ffc2-5b24-9ce7-533505286ade)

The Rat (#u563e660c-5b0c-5f4c-858b-25dcaad6ad67)

The Omen: November 2, 1991 (#ucbc997af-8d50-5d26-a878-00c58a940c51)

Disowned (#u33636f02-c1fe-5045-b7aa-8b8af6ac49a9)

The Happy Childhood (#ud65fb9bf-9a0f-5e8f-a28a-ac1827781e37)

Best Kisses! (#ufdd4ca49-c9c4-5377-b5d8-e803a4133b7b)

Obituary (#ue9ef5787-98d7-5491-a57e-a6488d429899)

“Boys Will Be Boys” (#u087099b8-4642-5164-9f68-e1a7fbffe1aa)

To Die For (#u013d892c-3af8-5b14-aa36-cf78e39a9f18)

“Accident” (#u139ad215-e9be-5e07-8ee1-b5645b995cc7)

Louisville Slugger (#u295604fe-3042-59fa-b89a-997c9bc06645)

The Little Sister (#u0ac288e2-c955-5942-b428-29ab05b10c3e)

The Promise (#u372ce898-c11c-5564-899a-2877cefda154)

The Siege (#uba2ce872-0b55-50c0-8945-02b3a3025782)

Because … (#u3dfc5992-cfe6-5b1c-ada2-a137695da4c2)

The Rescue (#ud1635568-c01f-53d8-b2cc-2b794e419694)

The Secret I (#u47e7b2c1-7a80-52fa-9223-726b75161b78)

The Secret II (#litres_trial_promo)

Final Confession (#litres_trial_promo)

“Dear Christ What Did Violet Do Now” (#litres_trial_promo)

The Revelation (#litres_trial_promo)

The Bat (#litres_trial_promo)

Safe House (#litres_trial_promo)

Runaway (#litres_trial_promo)

II (#litres_trial_promo)

“Praying for Violet” (#litres_trial_promo)

Exile (#litres_trial_promo)

Sleepwalker (#litres_trial_promo)

The Iceberg (#litres_trial_promo)

Turnip Face (#litres_trial_promo)

Sisters (#litres_trial_promo)

“Mr. Sandman Bring Me a Dream” (#litres_trial_promo)

“Dirty Girl” (#litres_trial_promo)

The Stalker: 1997 (#litres_trial_promo)

“You Are Not Wanted” (#litres_trial_promo)

Dirty Girl (#litres_trial_promo)

“Violet, Goodbye!” (#litres_trial_promo)

III (#litres_trial_promo)

The Scar (#litres_trial_promo)

The Burrow (#litres_trial_promo)

Valentine (#litres_trial_promo)

Keeping Myself Alive (#litres_trial_promo)

Off the Books (#litres_trial_promo)

Rat, Waiting (#litres_trial_promo)

Sorrowful Virgin (#litres_trial_promo)

Damned Little Dog (#litres_trial_promo)

Tongue (#litres_trial_promo)

Uncanny (#litres_trial_promo)

First Aid (#litres_trial_promo)

“Maxed-Out” (#litres_trial_promo)

The Misunderstanding (#litres_trial_promo)

The Return (#litres_trial_promo)

In My Mother’s Garden (#litres_trial_promo)

Forgiveness (#litres_trial_promo)

The Guilty Sister (#litres_trial_promo)

Howard Street (#litres_trial_promo)

Home (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgments (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Novels by Joyce Carol Oates (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

I (#ulink_be6d331c-fcc1-519e-813d-c0192e9178cc)

The Rat (#ulink_b9f66cb9-53ae-586c-bcd8-fb2ac1c3ca03)

Go away. Go to hell—rat!

You don’t get another chance to rat on anybody.

It’s true, you will not be given another chance.

There is just the one chance, the first.

The Omen:November 2, 1991 (#ulink_173b7f7a-e147-5875-afff-966a3494512f)

THIS, I WOULD REMEMBER: SMELLY DARK WATER IN THE RIVER near shore, the color of rotted eggplant, we’d seen on the way to school that morning and stopped to stare at.

On the Lock Street Bridge. Crossing on the pedestrian walkway. And there, directly below, the thunderous river (a deep cobalt-blue on clear days, metallic-gray on cloudy days) seemed to have changed color near shore and was purplish-dark, smelling of something like motor oil, roiling and surging as if it was alive like snakes, giant writhing snakes, you didn’t want to look but could not look away.

My sister Katie nudged me crinkling her nose against the smell. “C’mon, Vi’let! Let’s get out of here.”

I was leaning over the railing, staring down. Trying to see—were those actually snakes? Twenty-, thirty-foot-long snakes? Their scales were a winking deep-purple sheen. The sight was so terrifying, I’d begun to shiver convulsively. The odor was making me nauseated, and dizzy.

As far as we could see upstream the oily-purple water came in surges near shore while elsewhere the river was the color of stone, choppy and thunderous—the Niagara River rushing to the Falls seven miles to the north.

We ran from the walkway. Didn’t look back to see if the giant snakes were pursuing us.

I was twelve years old. This was the morning of the last day of my childhood.

(NOT OUR IMAGINATIONS. THE OILY PURPLE WATER LIKE SNAKES in the river had been real.

Alarmed citizens in South Niagara had noticed the phenomenon and reported it. There’d been many calls to local authorities and to 911.

On the front page of that evening’s South Niagara Union Journal it was curtly explained that the excessive discharge of sludge in the river that morning had been the result of routine maintenance of the Niagara County Water Board’s wastewater sedimentation basins and no cause for concern.

What did this mean? What was sludge?

When our father read the boxed item in the Journal he laughed.

“‘Routine.’ ‘Sedimentation’—‘no cause for alarm.’ Sons of bitches are poisoning us, that’s what it means.”)

Disowned (#ulink_43d362c3-92d9-5c25-bf8a-21550c1b09e9)

ONCE I’D BEEN DADDY’S FAVORITE OF HIS SEVEN KIDS. BEFORE something terrible happened between us, I am trying still to make right.

This was in November 1991. I was twelve years, seven months old at the time.

Sent me into exile. Thirteen years! To an adult that is not a long time—probably; but to an adolescent, a lifetime.

Who’s Daddy’s favorite little girl?

Violet Rue. Little Violet Rue!

When I was a little girl Daddy would kiss my pug nose, and make me squeal. And Daddy would lift me in his strong arms, and pretend to toss me into the air so I was frightened but did not let on for Daddy did not like scaredy-cat little girls.

There was an intensity to this, the lifting-in-the-arms, the impassioned speech. A delicious fiery smell, Daddy’s breath, fierce and unmistakable and I had no idea why, that he’d been drinking (whiskey) but knowing this ferocity to be the very breath of the father, the breath of the male.

How’s my little girl? Not afraid of your daddy are you?

Better not, Daddy loves his little Violet Rue like crazy!

ONCE, BEFORE I WAS BORN, MY OLDEST SISTER, MIRIAM, HAD BEEN Daddy’s favorite little girl. Later, my sister Katie had been Daddy’s favorite little girl.

But now, the favorite was Violet Rue. And would remain Violet Rue.

Because the youngest, the baby of the Kerrigan family.

Last-born. Most precious.

Daddy had named me himself—Violet Rue. A name he claimed to have heard in an Irish song that had haunted him as a boy.

It was said that Violet Rue had been an accidental pregnancy—a “late” pregnancy—but to the religious-minded nothing can be truly accidental.

All human beings have a special destiny. All souls are precious to God.

The family is a special destiny. The family into which you are born and from which there can be no escape.

Your mother was thrilled! A beautiful new girl-baby to take the place of the others who were growing up and growing away from her and especially the boys she hardly dared touch any longer, their downy cheeks, their prickly cheeks, the heat of their skin, fierce flushed faces she did not mean to surprise, opening a door without knocking, unthinking—Oh. Sorry. I didn’t think anyone was … Your big brothers who’d throw off Mom’s hand if even by chance she touched them.

A baby to love. A girl-baby to adore. The innocence of being loved totally and without question another time when she’d believed there would never be another time …

Of course, Lula was thrilled.

Of course, Lula was devastated. Oh God, oh Jesus no.

Hardly had she recovered from the last pregnancy—she’d determined would be the last. Thirty-seven years old—too old. Thirty pounds overweight. High blood pressure, swollen ankles. Kidney infection. Varicose veins like inky spiderwebs in her thighs fleshy-white as raw chicken.

And the man, the tall handsome Irish American husband. Turning his eyes from her, the bloated white belly, flaccid thighs, breasts like a cow’s udders.

His fault! Though he would blame her.

In private reproach he’d blamed her for years for she’d been the one who’d wanted kids and it was futile to remind him how he’d wanted kids too, how proud he’d been, the first babies, his first sons, dazed and boasting to his male friends he was catching up with them God damn it and boastful even to his father the old sod he couldn’t abide, as the old sod could not abide him.

And she’d been a beautiful woman. Beautiful body he’d been mesmerized by. Soft skin, astonishingly soft white breasts, curve of her belly, hips. Oh, he’d been crazy for her! Like a spell upon him. Those first years.

Six pregnancies. Not wanting to acknowledge—(except to her sister Irma)—that these were, just maybe, at least two pregnancies too many. And then, the seventh …

After the first pregnancy her body began to change. After the second, third. And after the fourth it began to rebel. Cervical polyps were discovered, that (thank God) turned out to be benign and could be easily removed. Another kidney infection. Higher blood pressure, swollen ankles. The doctor advised terminating the pregnancy. But Lula would never have consented. Jerome would never have consented.

It was not something that was discussed. Not openly and not privately. They were Catholics—that was enough. You just did not speak of certain things and of many of these things there were not adequate words in any case.

As boys went unquestioningly to war, in the U.S. military. You did not question, that was not how you saw yourself.

Those weeks, months your mother spent most of each day lying down. Terrified of a miscarriage and terrified that she might die. Praying for the baby to be born healthy and praying for her own life and in this way Lula Kerrigan not only lost her good looks (she’d taken for granted) but also became permanently frightened and anxious, superstitious. Looking for “signs”—that God was trying to tell her something special about herself and the baby growing in her womb.

A “sign” could be something glimpsed out a window—the figure of a gigantic angel in the clouds. A “sign” could be a dream, a mood. A sudden premonition.

In the later stages of her pregnancy no one could induce Lula to leave the house. So big-bellied, breathless and pop-eyed she’d become. Eating ravenously until she made herself sick. Gaining more weight. Knowing that her body disgusted her husband though (of course) (like any guilty husband) Jerome denied it. Last thing Lula Kerrigan wanted to do was expose herself to the eyes of others who’d be pitiless, mocking.

My God. Is that—Lula Kerrigan? Looking like an elephant! Making a spectacle of herself parading around like that.

Scornful expressions you would hear through your childhood, girlhood—making a spectacle, parading around. The harshest sort of denunciation a woman might make of another woman.

Parading around like she owns the place.

This would be charged of women and girls who exhibited themselves: their bodies. Particularly if their bodies were imperfect in obvious ways—too fat. Appearing in public when they should be ashamed of how they looked or in any case aware of how they looked. Of how unsparing eyes would latch onto them, assessing. Never was such a charge made of men or boys.

There appeared to be no masculine equivalent for making a spectacle, parading around.

As, you’d discover, there was no masculine equivalent for bitch, slut.

The Happy Childhood (#ulink_43e51ffc-6549-5907-89fa-dba3c818fd31)

WE WERE JEROME JR., AND MIRIAM, AND LIONEL, AND LES, and Katie, and Rick, and Violet Rue—“Vi’let.”

“Christ! Looks like a platoon.”

Daddy would stare at us with a look of droll astonishment like a character in a comic strip.

But (of course) Daddy was proud of us and loved us even when he had to discipline us. (Which wasn’t often. At least not with the girls in the family.)

Yes, sometimes Daddy did get physical with us kids. A good hard shake, that made your head whip on your neck and your teeth rattle—that was about the limit with my sisters and me. My brothers, Daddy had been known to hit in a different way. Haul off and hit. (But only open-handed, never with a fist. And never with a belt or stick.) What hurt most was Daddy’s anger, fury. That look of profound disappointment, disgust. How the hell could you do such a thing. How could you expect to get away with doing such a thing. The expression in Daddy’s eyes, that made me want to crawl away and die in shame.

Disciplining children. Only what a good responsible parent did, showing love.

Of course, our father’s father had disciplined him. Nine kids in that rowdy Irish Catholic family. Had to let them know who was boss.

One by one the Kerrigan sons grew up, to challenge their father. And one by one the father dealt with them as they deserved.

Old sod. Daddy’s way of speaking of our grandfather when our grandfather wasn’t around.

So much of what Daddy said had to be interpreted. Laughing, shaking his head, or maybe not laughing, exactly. Old sod bastard. God-damned old sod.

Still, when our grandfather had nowhere else to live, Daddy brought him to live with us. Fixed up a room at the rear of the house, that had been a storage room. Insulation, new tile floor, private entrance so Granddad could avoid us if he wished. His own bathroom.

Daddy’s birth name was Jerome. This name was never shortened to “Jerry” let alone “Jerr”—even by our mother.

Our mother’s name was Lula—also “Lu”—“Lulu”—“Mommy”—“Mom.”

When speaking to us our parents referred to each other as “your father”—“your mother.” Sometimes in affectionate moments they might say “your daddy”—“your mommy”—but these moments were not often, in later years.

In early years, I would not know. I had not been born into my parents’ early, happier years.

Between our parents there was much that remained unspoken. Now that I am older I have come to see that their connection was like the densely knotted roots of trees, underground and invisible.

Frequently our father called our mother “hon”—in a neutral voice. So bland, so flat, you wouldn’t think that “hon” was derived from “honey.”

If he was irritated about something he called her “Lu-la” in a bitten-off way of reproach.

If he’d been drinking it was “Lu-laaa”—playful verging upon mocking.

At such times our mother was still, stiff, cautious. You did not want to provoke a husband who has been drinking even if, as it might seem, the man is in a mellow mood, teasing and not accusing. No.

Fact is, much of the time we saw our father, later in the day, he’d been drinking. Even when there were no obvious signs, not even the hot fierce smell of his breath.

Mom had a way of communicating to us—Don’t.

Meaning Don’t provoke your father. Not right now.

This Mom could communicate wordlessly with a sidelong roll of her eyes, a stiffening of her mouth.

Your father loves you, as I do—so much! But—don’t test that love …

A painful truth of family life: the most tender emotions can change in an instant. You think your parents love you but is it you they love, or the child who is theirs?

Like leaning too close to the front burner of the stove, as I’d done as a small child, and in an instant my flammable pajama top burst into flame—you can’t believe how swiftly.

But swiftly too as if she’d been preparing for such a calamity for all of her life as a mother, Mom grabbed me, pulled me away from the stove, hugging me, snuffing out the fierce little flames with her body, bare hands smothering the flames, before they could take hold. And trembling then, lifting me to the sink and running cold water over my arms, my hands, just to make sure the flames were gone. Almost fainting, she’d been so frightened. We won’t tell Daddy, sweetie, all right?—Daddy loves you so much he would just be upset.

Comforting to hear Mom speak of Daddy. As if in some way he was her Daddy, too.

And so when Mom called Daddy “Jerome” it was in a respectful voice. Not a playful voice and not an accusatory or critical voice but (you might say) a voice of wariness.

Oh Jerome. I think—we have to talk …

The hushed voice I would just barely hear through the furnace vent in my room in the days following Hadrian Johnson’s death.

EVEN NOW. SO MANY YEARS LATER. THAT STRONG WISH TO CRAWL away, die in shame.

WHEN I WAS A LITTLE GIRL IN THE EARLY 1980S MY FATHER WAS A tall solid-built man with dark spiky hair, hard-muscled arms and shoulders, a smell of tobacco on his breath, and (sometimes) a smell of beer, whiskey. His jaws were covered in coarse stubble except when he shaved, an effort made grudgingly once a week or so by one not willing to be a bearded man but thinking it effeminate to be close-shaven too. By trade he was a plumber and a pipe fitter and something of an amateur carpenter and electrician. In the army he’d been an amateur boxer, a heavyweight, and while we were growing up he had a punching bag and a heavy bag in the garage where he sparred with other men, and with my brothers as they came of age, who could never, not ever, quick on their young legs as they were, avoid their father’s lightning-quick right cross. It was the great dream of my oldest brother Jerome—“Jerr”—that he might someday knock Daddy down on his rear, not out but down; but that never happened.

And Lionel, Les, Rick. He’d made them all “spar” with him, laced big boxing gloves on their hands, gave them instructions, commanded them to Hit me! Try.

We watched. We laughed and applauded. Seeing one of our brothers trying not to cry, wiping bloody snot from his reddened nose, seeing our father release a rat-a-tat of short stinging right-hand blows against a bare, skinny, sweating-pale chest—why was that funny? Was that funny?

Try to catch me, li’l dude. C’mon!

Hey: you’re not giving up until I say so.

Girls were exempt from such humiliations. My sisters and me. But girls were exempt from instructions too. And Daddy’s special glow of approval, when at last one of our brothers managed to land a solid blow or two, or keep himself from falling hard on his ass on the cement floor of the garage.

Not bad, kid. On your way to the Golden Gloves!

Daddy’s girls had to suppose that Daddy was proud of us in other ways, it wasn’t clear how just yet.

He wanted us to be good-looking, which might mean sexy—but not too obviously. Staring at Miriam—her mouth, lipstick—not knowing what to think, how to react: Did he approve, or disapprove?

He’d seemed to be impressed by good grades but report cards were not very real to him, school was a female thing, he’d dropped out of high school without graduating, never read a book nor even glanced inside a book so far as I knew, pushed aside our textbooks if they were in the way on a counter, no curiosity except just once that I remember, pushing aside a book I’d brought home from the public library—The Diary of Anne Frank.

What was this, he’d heard of this, vaguely—in the newspaper, or somewhere—Anne Frank. Nazis?

But Daddy’s interest was fleeting. He’d peered at the cover, the wan girl-face of the diarist, saw nothing to particularly intrigue him, dismissed the book as casually as he’d noticed it without asking me about it. For always Daddy was distracted, busy. His mind was a kaleidoscope of tasks, things to be done, each day a ladder to be climbed, nothing random admitted.

And what pride we felt, my sisters and me, seeing our father in some public place, beside other, ordinary men: taller than most men, better-looking, with a way of carrying himself that was both arrogant and dignified. No matter what Daddy wore, work clothes, work boots, leather jacket he looked good—manly.

And the expression on our mother’s face, when they were together, with others. That particular sort of female, sexual pride. There. That’s him. My husband Jerome. Mine.

To their children, parents are not identical. The mother I knew as the youngest of seven children was certainly not the mother my older siblings knew, who’d been a young wife. Especially, the father I knew was not the father my brothers knew.

For Daddy treated my brothers differently than he treated my sisters and me. To Daddy the world was harshly divided: male, female.

He loved my brothers in a way different from the way he loved my sisters and me, a fiercer love, a more demanding love, mixed with impatience, at times even derision; a hurtful love. In my brothers he saw himself and so found fault, even shame, a need to punish. But also a blindness, a refusal to detach himself from them.

His daughters, his girls, Daddy adored. You would not have said of any Kerrigan that he adored his sons.

We were thrilled to obey him, we basked in his attention, his love. It was a protective love, a wish to cherish but also a wish to control, even coerce. It was not a wish to know—to know who we were, or might be.

Yet, Daddy behaved differently with Miriam, and with Katie, than he did with me. It was a subtle difference but we knew.

He’d have claimed that he loved us all equally. In fact, he’d have been angry if anyone had suggested otherwise. That is what parents usually claim.

Until there is a day, an hour, when they cease making that claim.

TWO FACTS ABOUT DADDY: HE’D FOUGHT IN VIETNAM, AND HE’D come back alive and (mostly) undamaged.

This was about as much as Daddy would say about his years as a soldier in the U.S. Army, when Lyndon B. Johnson was president.

“I enlisted. I was nineteen. I was stupid.”

We knew from relatives that Daddy had been “cited for heroism” helping to evacuate wounded soldiers while wounded himself. He’d been awarded medals—kept in a box in the attic.

My brothers tried to get him to talk about being a soldier in the U.S. military and in the war but he never would. In a good mood after a few ales he’d concede he’d been God-damned lucky the shrapnel that got him had been in his ass, not his groin, or none of “you kids” would’ve been born; in a not-good mood he’d say only that Vietnam had been a mistake but not just his mistake, the whole country had gone bat-shit crazy.

He’d hated Nixon more than Johnson, even. That a president would lie to people who trusted him and not give a damn how many thousands of people died because of him, Daddy shook his head, speechless in indignation.

Most politicians were those blood-sucking sons of bitches. Cocksuckers. Fuckers. Even Kerrigan relatives who were involved in local, western New York State politics were untrustworthy, opportunists and crooks.

Daddy would only talk about Vietnam with other veterans. He had a scattering of friends who were veterans of Vietnam, Korea, and World War II he went out drinking with, but never invited to the house; our mother did not know their wives, and our father had no interest in introducing her. Taverns, saloons, pubs, roadhouses—these were the gathering places of men like Daddy, almost exclusively male, relaxed and companionable. In such places they watched championship boxing matches, baseball and football, on TV. They laughed uproariously. They smoked, they drank. No one chided them for drinking too much. No one waved away smoke with prissy expressions. Who’d want women in such places? Women complicated things, spoiled things, at least women who were wives.

Returning home late from an evening with these men Daddy was likely to be heavy-footed on the stairs. Often he woke us, cursing when he missed a step, or collided in the dark with something.

If one of us left something on the stairs, textbook, pair of shoes, Daddy might give it a good kick out of pure indignation.

In our beds, we might hear them. Our mother’s murmurous voice that might be startled, pleading. Our father’s voice slurred, abrasive, loud.

A sound of a door being slammed, hard. And though we listened with quick-beating hearts, often we heard nothing further.

Katie had hoped to interview our father for a seventh-grade social studies project involving “military veterans” but this did not turn out well. Calm at first telling her no, not possible but when Katie naively persisted losing his temper, furious and profane, threatening to call the teacher, to tell that woman to go fuck herself until—at last—our mother was able to persuade him not to make such a call, not to jeopardize Katie’s standing with her teacher or at the school, please just forget it, try to forget, the teacher had only meant well, Katie was in no way to blame and should not be punished.

Punished was something our father could understand. Punished unfairly, he particularly understood.

Katie would remember that incident for the rest of her life. As I will, too.

You didn’t push Daddy, and you didn’t take Daddy for granted. It was a mistake to assume anything about him. His generosity, his pride. Dignity, reputation. Not being disgraced or disrespected. Not allowing your name to be dragged through the dirt.

There were many Kerrigans scattered through the counties of western New York State. Most of these had emigrated from the west of Ireland, in and near Galway, in the 1930s, or were their offspring. Some were closely related to our father, some were distant, strangers known only by name. Some were relatives whom we saw frequently and some were estranged whom we never saw.

We would not know why, exactly. Why some Kerrigans were great guys, you’d trust with your life. Others were sons of bitches, not to be trusted.

We did notice, my sisters and me, that girl-cousins with whom we’d been friendly, and liked, would sometimes become inaccessible to us—their parents were no longer on Daddy’s good side, they’d been banished from Daddy’s circle of friends.

If we asked our mother what had happened she might say evasively, “Oh—ask your father.” She did not want to become involved in our father’s feuds because a remark of hers might get back to him and anger him. Personal questions annoyed our father and we did not want to annoy our father whom we adored and feared in about equal measure.

For instance: What happened between our father and Tommy Kerrigan, an older relative who’d been a U.S. congressman and mayor of South Niagara for several terms? Tommy Kerrigan was the most prominent of all the Kerrigans and certainly the most well-to-do. He’d been a Democrat at one time, and he’d been a Republican. He’d had a brief career as an Independent—a “reform” candidate. He’d been a liberal in some issues, and a conservative in others. He’d supported local labor unions but he’d also supported South Niagara law enforcement, which was notorious for its racist bias against African Americans; as a mayor he’d defended police killings of unarmed persons and had blatantly campaigned as a “law and order” candidate. Tommy Kerrigan was a “decorated” World War II veteran who supported American wars and military interventions, unquestioningly. He supported the Vietnam War until the U.S. withdrew troops in 1973 and it was his belief that Richard Nixon had been “hounded” out of office by his enemies. Naturally Tommy Kerrigan was critical of rallies and demonstrations against the war which he considered “traitorous”—“treasonous.” He defended the actions of the police in dealing roughly with antiwar protesters as they’d dealt roughly with civil rights marchers in an earlier era. After a scandal in the early 1980s he’d had to abruptly retire from public life, narrowly escaping (it was said) indictment for bribe taking and extortion, but he continued to live in South Niagara, in a showy Victorian mansion in the city’s most prestigious residential neighborhood, and he was still exerting political influence in circuitous ways while I was growing up. It was speculated that there’d been bad blood between Tom Kerrigan and our father’s father and so out of loyalty our father was permanently estranged from Tom Kerrigan as well. When a softball field was built in South Niagara and given the name Kerrigan Field no one in our family was invited to the dedication and the opening game; if our brothers played baseball at Kerrigan Field, they knew better than to mention the fact to our father.

Carefully Daddy would say of Tom Kerrigan that there was no love lost between our families though at other times he might shake his head and admire Tom Kerrigan as the most devious son of a bitch since Joe McCarthy.

And if anyone asked us if we were related to Tom Kerrigan, Daddy laughed and said, tell them politely No. I am not.

WE LIVED IN A TWO-STORY WOOD FRAME HOUSE AT 388 BLACK Rock Street, South Niagara, that Daddy kept in scrupulous repair: roof, gutters, windows (caulked), chimney, shingle board sides painted metallic-gray, shutters navy blue. When the front walk began to crack, Daddy poured his own cement, to replace it; when the asphalt driveway began to crack and shatter, Daddy hired a crew to replace it under his direction. He knew where to buy construction materials, how to buy at a discount, he scorned using middlemen. In the long harsh winters of heavy snowfall in South Niagara Daddy made sure our walk and driveway were shoveled properly, not carelessly as many of our neighbors’ walks and driveways were shoveled; in warmer months, Daddy made sure that our (small) front yard and our (quarter-acre) backyard were kept properly mowed. My brothers did much of this work, and sometimes my older sisters, and if Daddy wasn’t satisfied that the task had been done well, he might finish it himself, in a fury of disgust. By trade he was a plumber and a pipe fitter but he’d taught himself carpentry and he dared to undertake (minor) electrical work for he resented paying other men to do anything he might reasonably do himself. It wasn’t just saving money, though Daddy was notoriously frugal; it had to do with pride, integrity. If you were a (male) Kerrigan you were quick to take offense at the very possibility that someone might be taking advantage of you. Being made a fool of was the worst of humiliations.

As long as I lived in the house on Black Rock Street, as far back as I could remember, a project of Daddy’s was under way: replacing linoleum on the kitchen floor, replacing the sink, or the counter; repainting rooms, or the entire outside of the house; hammering shingles onto the roof, building an addition at the rear of the house where for a few difficult years, Daddy’s elderly, ailing father would live, convulsed in coughing fits that sounded like gravel being rapidly, roughly shoveled.

Daddy was a perfectionist and could not walk away from anything he believed to be half-assed.

Daddy kept a sharp eye on neighbors’ houses, properties. He did not much care that lawns at other houses were scrubby and burnt out in the summer but he did care if grass wasn’t mowed at reasonable intervals, if it grew tall enough to look unsightly, and to go to seed; he cared if trees were allowed to become diseased, and to shed their limbs on the street. He cared very much if properties on our block of Black Rock were allowed to grow shabby, derelict. Particularly, Daddy grew upset if a house was allowed to go vacant, for bad things could come of vacant properties, he knew from his own boyhood with his brothers and cousins raising hell in places not properly supervised.

Back of our house was a yard that seemed large, and deep, running into municipal-owned uncultivated acreage on the steep bank of the Niagara River. There were trees of which Daddy was proud—a tall red maple that turned fiery-red and splendid in October, an even taller oak, a row of evergreens. (But Daddy was unsentimental about cutting down the oak after it was damaged by a windstorm, and he feared it might be blown down onto the house; he’d cut it down himself with a rented chain saw.) My mother tried to cultivate beds of flowers, with varying degrees of success: wisteria, peonies, day lilies, roses assailed by Japanese beetles, slugs, black rot and mold, that often defeated her by mid-summer for Mom could not enlist her older children’s help with the property as Daddy could.

Our house was at the dead end of Black Rock Street above the river.

I cried a lot when I was sent away. Any river or stream I saw, even on TV or in a photograph, tears would be triggered. You have to get hold of yourself, Violet. You will make yourself sick. You can’t—just— keep—crying … My aunt Irma pleaded with me.

The poor woman, I was not nice to her. She could not bear a broken heart in a child impossible to heal by any effort of her own.

No matter how far away I came to live from the Niagara River, it has gotten into my dreams. For it is not like most other rivers—relatively short (thirty-six miles), and relatively narrow (at its widest, eighty-five hundred feet), and exceptionally fast-moving and turbulent. As you approach the river calls to you—whispers that become ever louder, deafening. The river is turbulent like a living thing shivering inside its skin. Miles from the thunderous falls like a nightmare that calls—Come! Come here. Strife and suffering are absolved here.

That morning in December when you wake to see that the river has frozen all the way across, or nearly; corrugated black ice with a fine light dusting of snow over it, the eye registers as beauty.

But I had a happy childhood in that house. No one can take that from me.

Best Kisses! (#ulink_9ea81a1a-f5f2-5f73-89ff-806abbad75ef)

A GAME. A HAPPY GAME. THE WAY MOM WOULD STOOP OVER to kiss me, suddenly.

When I was a little girl. Best kisses come by surprise!

Lacing her (strong) fingers through my (smaller) fingers. Securing my fingers with hers. Preparing to cross a busy street. Ready. Set. Go!

A long time ago when Mommy loved me as much as Daddy did. When I knew (without needing to be told) that Mommy would take care of me and keep me from harm even if this harm was Daddy.

“IT’S EASY TO LOVE THEM WHEN THEY’RE LITTLE”—MOM LAUGHED, talking with a friend. “Later, not so easy.”

Obituary (#ulink_a1ea4756-607b-5b26-afe1-97a3a26b57d0)

THIS CLIPPING FROM THE SOUTH NIAGARA UNION JOURNAL I saved until it became so dry it fell into pieces in my fingers. An obituary beneath a photograph of a shyly smiling black boy with a gap between two prominent front teeth. Seventeen when he’d died but in the photo he looks as if he could be fifteen, even fourteen.

Hadrien Johnson, 17. Resident of 29 Howard Street, South Niagara. Varsity softball and basketball at South Niagara High School. Honor roll 1, 2, 3. Youth Choir, African Methodist Episcopal Church. Died in South Niagara General Hospital, November 11, 1991, of severe head wounds following an attack in the late evening of November 2 by yet-unidentified assailants as he was bicycling to his home. Survived by his mother, Ethel, his sisters, Louise and Ida, and his brothers, Tyrone, Medrick, and Herman. Services Monday at African Methodist Episcopal Church.

People would ask if I’d known Hadrian Johnson. (The name was misspelled in the newspaper obituary but corrected in subsequent articles.) No! I had not known him—he was a junior at the high school, I was in seventh grade. His sister Louise was a year older than me, at the middle school, but I did not know Louise either.

There were no African American classmates I knew well. All of my friends were white like me and all of them lived within a few blocks of our house on Black Rock Street.

It was only after his death that I came to know Hadrian Johnson. It was only after his death that we came to be associated in people’s minds. Hadrian Johnson. Violet Rue Kerrigan.

Not that it did any good for Hadrian Johnson, who was dead. And it was the worst thing that could have happened to Violet Rue Kerrigan.

“Boys Will Be Boys” (#ulink_b32fafa4-c758-5bcf-89da-48322eee8f14)

WAS IT WONDERFUL TO HAVE BROTHERS WHEN YOU WERE growing up? Older brothers? Who could look out for you?

Girls lacking older brothers would ask me. How wistful they were! Having to fend on their own.

I didn’t just adore my brothers, I was proud of them. Just the fact—My big brothers! Mine.

For girls are keenly sensitive of needing to be looked after. In certain circumstances, like school. Not to be alone, exposed, unprotected. Vulnerable.

Not measurable but very real—the power of older brothers to forestall teasing, bullying, harassment, threats from other boys made against girls. The protective power of older brothers by their mere existence.

The sexual threat of boys is greatly diminished, by the (mere) existence of a girl’s brothers.

Unless of course the girl’s brothers are themselves the (sexual) threat.

Parents have not a clue. Cannot guess. The (secret) lives of children, adolescents. Thinking that, because we are quiet, or docile (seeming), because we smile on cue and seem happy, because we are no trouble, that our inner lives are placid, and not churning and choppy and terrifying as the Niagara River as it gathers momentum rushing to the Falls.

Did you adore your brothers, Vi’let?

Sure, you had to!

IT’S TRUE. I ADORED MY BROTHERS.

Not so much Rick, the youngest, who resembled me temperamentally, and who was a reasonably good student, as I was, and sweet-natured, but the other, older boys—Jerr, Lionel, Les.

They were quick-tempered and loud and impatient and bossy. Out of the earshot of adults they were profane, even obscene. They were funny—crass and crude. And loud—did I say loud? Voices, footsteps. On the stairs. Opening and shutting doors. Colliding with me if I didn’t get out of their way.

Ignoring me, usually. Of course, why’d my brothers take note of me?

They were not so polite to Mom, sometimes. Mouthy, she’d call them. But in our father’s presence, they were watchful, wary. They behaved.

If Daddy became annoyed with one of them he had ways of disciplining: sometimes a sharp, level look; sometimes an uplifted hand, the flat of the hand, a fist.

Flick of Devil-Daddy tongue which the boys could not miss. Hot red, sharp-pointed tongue like a blade slicing their hearts. But in the next instant, gone.

Even so, outside the house the older Kerrigan boys sometimes got into trouble.

Almost there was a hushed reverent air to the phrase—into trouble.

The first time I was too young to know what had happened. Nor did Katie know. And if Miriam knew, she wouldn’t tell us.

On the phone with relatives our mother spoke derisively: “It’s nothing. It’s a stupid rumor. Those liars.”

Though sometimes her voice quavered: “It’s her word against theirs! That’s what everybody says, and that’s a legal fact.”

Near-inaudibly Mom would speak into the phone, in the kitchen. Seated, hunched over, pressing the avocado-plastic receiver against her ear as if trying to keep the words inside from spilling out.

If Katie asked what was going on Mom said, scolding: “Never mind! It’s no business of you girls.”

You girls. Often we’d hear from Mom’s mouth.

Her gaze avoiding us, skittering away across the linoleum floor.

We were mystified but we knew better than to persist in questions. We knew better than to ask our brothers who were the ones in trouble. (And if we asked Rick he’d shrug us off—Don’t ask me, ask them.) No possibility of asking our father who was the custodian of all secrets and didn’t take kindly to being questioned about anything. And eventually we learned what had happened, or some version of what had happened, as we learned most things not meant for us to know, piecing together fragments of stories as our mother sometimes, with a curious sort of self-punishing patience, fitted together broken crockery to mend with glue.

The girl whose word was against theirs was a fourteen-year-old special-needs student at the middle school where Lionel was in ninth grade. Jerr was sixteen, a junior at the high school.

Liza Deaver was the name. Liza Lizard she was called for her face was splotched like a turtle’s shell.

At fourteen she had the body of a mature woman, fattish, slow-moving, with thick plastic-rimmed glasses and lenses that magnified her eyes. She wore slacks with elastic waistbands and plaid shirts that billowed loose over her big soft breasts and belly. We’d overheard our brothers imitating her speech which was slow and stammering and whining like the speech of a young child.

Liza’s mental age was said to be nine or ten. And it would remain that age through her life.

Liza was physically clumsy, poorly coordinated, and often made her way swaying and lurching with one eye shut, as if seeing with both eyes confused her. Oddly, unpredictably, Liza sometimes burst out in anger and tears and had to be sent home from school by the special-needs teacher.

We’d heard that, in the special-needs classroom at the school, Liza had some talent for drawing. Except her drawings were of people with large round balloon-faces on small stick legs—just faces, legs.

Retards, they were called. Special-needs was the adult term, retards what others kids called them.

Liza Lizard was a cruel name. Yet sometimes it seemed, if boys called this name after her, Liza misheard it, and thought it might be something else, and turned to them with a peculiar squinting smile, a childish sort of hope.

I did not—ever—utter aloud the name Liza Lizard. But like other girls I may have sniggered when I heard it.

It is shameful now to recall—Liza Lizard. You did not—ever—want the attention of the crude coarse cruel boys to turn upon you and so possibly, yes—you did snigger when you heard it.

No news item about the incident in Patriot Park would appear in the South Niagara Union Journal. Only minors were involved, and the (alleged) victim so unreliable.

Sometimes in Liza Deaver’s confused telling there were just five or six boys involved. Sometimes, many more—ten, twelve.

Sometimes Liza Deaver remembered a few names. Sometimes, just one or two.

What would come to be generally known was that a loose group of boys between the approximate ages of fourteen and seventeen, not a gang, not even friends had cajoled Liza into coming with them to Patriot Park after school. One of the older boys, not a Kerrigan, had been friendly with Liza, or rather had pretended to be friendly with Liza, so Liza would boast that he was my boyfriend.

The Kerrigan brothers Jerome Jr. and Lionel were not the ringleaders in the assault—if there was an “assault.” This was much-reiterated by my brothers. All they’d done (they would claim) was follow other boys tramping through muddy playing fields and past skeletal trellises in the municipal rose garden to the swimming pool, to the weatherworn stucco building where refreshments were sold in summer and where there were foul-smelling restrooms and changing rooms. In the off-season the building was deserted, dead leaves blew about the cement walk. But the restrooms were kept unlocked through the year.

The boy who was Liza Deaver’s “boyfriend” led Liza into the men’s room saying they had “nice surprises” for her.

It was so, Liza Deaver liked “surprises.” Usually candy bars, snacks in cellophane wrappers from a corner store, cans of sugary soda pop. Sometimes these were given to her by kindly persons who knew her and her family and sometimes by others who were not so kindly.

Questioned afterward by parents, school authorities, Family Court officers the boys would claim that Liza had “wanted” to come with them. Going to the park had been “her idea.” Into the men’s restroom, her idea. She’d told them that she had done such things with her brothers and other boys and sometimes they gave her “surprises,” and sometimes they didn’t.

Liza Deaver denied this. Liza’s parents denied it, adamantly.

Liza Deaver had not been injured enough to require hospitalization but she’d been examined in an emergency room and treated for cuts, bruises, bloodied nose and teeth, “chafings” in the vaginal and anal areas. Clumps of hair had been pulled from her head and (it was whispered) the boys had “grabbed and pulled out” pubic hairs of which (it was whispered) Liza had many.

Still the boys insisted that it had been Liza’s idea. They’d been “nice” to her, they said. These gifts they’d given her: a Mars bar with just a small bite missing, a plastic bead necklace found in the trash, a small stuffed puppy with button eyes, a perfumy deodorant. (Liza Deaver was notorious for her strong, horsey odor.) It was not clear how long Liza remained in the restroom with the boys for Liza lacked a firm grasp of the passage of time but the boys insisted that it had been for “only a few minutes”—“definitely no more than a half hour.” It was 5:40 P.M. by the time Liza limped home, a distance of about a mile; it was estimated that the boys had led Liza away from school at 3:30 P.M., though accounts differed about who exactly had been with Liza from the first, and who had joined later. The fact that Liza had brought home with her the “gifts” the boys had given her seemed to suggest that she’d been happy to receive them, for otherwise—wouldn’t she have thrown them away, in disgust?

If she’d been victimized by the boys, and not a willing companion, wouldn’t she have called for help as soon as they’d released her, and she was able to run out into the street?

(Though it wasn’t clear that the boys had kept Liza in the restroom against her will. She hadn’t been a captive, they said; she’d wanted to stay, and only left because it was suppertime, and she suddenly remembered that her parents would be angry with her if she was late.)

Eventually, it was established that there were at least seven boys involved in the incident. These included Jerome Kerrigan Jr. and his brother Lionel but not (it seemed) Les. (Certainly not Rick.) No doubt there were more boys but the seven who were named refused to provide the names of other boys—they were not rats.

Poor Liza! Questioning left her confused about the boys’ names but she could (more or less) identify them by other means, descriptive means and by studying pictures.

Yes she’d gone into the park and into the restroom with them willingly but when she’d wanted to leave they had not let her leave. Yes she’d been held captive by them, in the restroom. No she had not wanted to do the “nasty” things they did to her.

Yes she had told them she wanted to go home. Yes she had started to cry but they just laughed at her. No no no she had not told them that her brothers had done these nasty things to her, and other boys and men beside. She had not.

It was not clear if Liza had intended to tell her parents that “something bad” had happened to her. After they’d released her she’d slipped into her house by a rear door and was discovered by her mother in a flushed and disheveled state, clothes soiled and torn and misbuttoned, and her face smeared with blood. At once, confronted by her frightened mother, Liza burst into tears and began stammering and sobbing.

It was the “worst day” of their lives, Mrs. Deaver said. They would “never, not ever” recover from what had been done to their daughter whose fault was she was “too friendly” to people who were not her friends.

The Deavers lived in a ramshackle house on Carvendale Road, at the edge of the school district. On one side of the road was the township of South Niagara, on the other side an unincorporated region of scrubby farmland, overgrown pastures and derelict dwellings.

The Deavers were a large family but not as the Kerrigans were a large family. For the Deavers were a welfare family whose father could not provide for his wife and many children—nine? Ten? And of these, what a pity, what a shame, unless it was a crime, as people said, several were not right in the head—what the kids called retards.

Mr. Deaver, when he was employed, worked at the railroad yard. Mrs. Deaver worked part-time at a local mall. Several of their children were out of school and only intermittently employed and the youngest had not yet begun school.

At Family Court, Liza initially sat mute and frightened as others spoke on her behalf. Her deep-shadowed eyes were swimmingly magnified behind the thick lenses of her glasses. After a while she began to answer questions in a hushed, hoarse voice. Eventually she began to speak louder. And then she began to cry, to sob, to stammer, to stutter and to choke. Her splotched-turtle face was flushed and puffy, saliva glistened at her lips. Family Court officials who tried to make transcripts of her not-very-coherent and contradictory accounts would insist afterward that they felt sorry for the “poor, mentally disabled girl”—and for the Deavers, who accompanied Liza and never let her out of their sight—(Mrs. Deaver went with Liza several times to the restroom during the course of the session)—were nonetheless unconvinced that Liza was telling the truth or even that with her impaired cognition she had a clear conception what truth might be.

It was generally conceded—Boys will be boys. And—These boys’ lives might be ruined … How much worse the situation might have turned out for the boys, if the girl had been seriously hurt!

There were extensive interviews with the accused boys by Family Court officers, with the boys’ fathers and their attorney present. (The fathers of the accused boys hired a single lawyer to represent their sons, a local lawyer with connections to the Kerrigan family.) In this way a public hearing in juvenile court was avoided. There were no arrests. No formal charges were made against the boys who were suspended from school for one week.

Liza Deaver was placed on suspension for the remainder of the school year for it was believed that her presence would be “distracting” and “hazardous,” in the words of the school principal; Liza herself was known to have a raging temper, and to strike out furiously, in frustration, at younger and smaller children when she believed they didn’t respect her. (Liza was usually intimidated by individuals older than herself.) As it happened Liza Deaver never returned to school but was allowed to drop out for “medical reasons.”

All this my sister Katie and I would learn, much later. At the time, we knew little.

No one in the family talked about Liza Deaver, so far as we knew.

No one talked about the trouble. For weeks Jerr and Lionel were subdued around our mother and wary of our father, like kicked dogs. But cunning kicked dogs. They had 9:00 P.M. curfews. Jerr wasn’t allowed to drive for six weeks. Both boys had extra chores around the house. On the phone my mother said, incensed, “It was all that girl’s fault! She did it deliberately! Those Deavers better get her fixed! Before it’s too late.”

When my mother hung up I asked what “fixed” meant. I wondered if whatever the boys had done to her, Liza might need fixing like a broken clock.

Disdainfully my mother said, “Like a cat, spayed. So it can’t have kittens people have to drown.”

To Die For (#ulink_2d50ef91-a138-523d-8abe-80e427789de9)

GROWING UP, WE KERRIGAN KIDS KNEW THAT OUR DADDY would die for us. No one had to tell us, we knew. Of course, the concept “to die for” was not in our vocabularies. Still, we knew.

In our father’s big Irish Catholic family in Niagara Falls he’d been raised with the conviction that families stuck together. Irish immigrants had had a hell of a hard time coming to America, hadn’t even been considered “white” in some quarters, like Italians, Greeks, and Jews, until even the 1950s. And so, the Irish stuck together, in theory at least.

Not in theory, but in reality, and crucially, a family had to protect its own. You might quarrel with relatives, a brother or a sister, you might quarrel with your parents but essentially you stuck together, you never deserted or betrayed one another. You never went outside the family—that was unforgivable.

Inside the family you never lied when it really mattered, and you never cheated.

Siding with your brother against your cousin, but with brother and cousin against the stranger.

You would die for your family and you would (maybe) die for your (close) friends the way soldiers would die for their (close) buddies.

Something like this, Jerome Kerrigan had truly seemed to feel for his immediate family, if not all of the Kerrigans. And for the guys in his platoon in Vietnam, he dared not recall without his eyes welling with tears and his mouth working to keep still.

If Daddy was suspicious of strangers he was almost naively trusting of relatives and friends. Often he did household repairs for no payment, wouldn’t hear of being paid except in drinks, hospitality, reciprocal favors. That was friendship—loyalty, paying back what you owed. Being generous.

He lent money to people who, he had reason to know, probably wouldn’t be able to repay him; he lent money without interest, knowing that this was a disadvantage, for those to whom he’d lent money would repay the lenders who’d demanded interest, and not him. Yet, Daddy could not bring himself to lend money with interest—that was not how he saw himself.

And so, Daddy lent money to his heavy-drinking brothers. He provided bail bond for Kerrigans who found themselves on the wrong side of the law—business fraud, bad checks, failure to pay alimony, embezzlement. He did favors for guys in the plumbers’ union, for guys he’d gone to school with who’d had bad luck. He respected bad luck—it could happen to anyone.

The more kids you have, the more possibilities for bad luck. That was a grim fact.

The most extravagant thing Daddy did, that I remember from my childhood, was helping one of his younger sisters buy a house in Buffalo, so that she and her husband could live near her husband’s family, who would help her nurse her husband afflicted with some terrible wasting disease like multiple sclerosis. Our mother had not liked this arrangement, she’d sighed and fretted and all but wept over the phone, for a large amount of money was involved, but in Daddy’s presence she did not dare complain for, as Daddy would’ve pointed out to her, he was the one with a salary.

At the same time, you did not wish to cross Jerome Kerrigan.

You did not wish to find yourself on his shit list. For there were many on this list who were, in Daddy’s eyes, fucked.

Forgiving was rare. Forgetting, rarer.

And the closest you were to Daddy, the harder for Daddy to forgive.

He liked to quote an Italian adage—Revenge is a dish best served cold.

Another remark he favored from the boxing world was What goes around comes around. Which was more hopeful for it seemed to mean not just bad but good, too. The good you do will be returned to you. Eventually.

“Accident” (#ulink_1941834f-f2a3-52c2-8a97-4538a2764c14)

IN NOVEMBER 1991 WHEN HADRIAN JOHNSON WAS BEATEN UNCONSCIOUS and left to die on the shoulder of Delahunt Road, and the lawyer who’d defended Jerome Jr. and Lionel Kerrigan at the time of Liza Deaver pleaded their case to prosecutors, the defense of boys will be boys didn’t work so well for them, or for my cousin Walt Lemire and a neighborhood friend named Don Brinkhaus who was also involved in the beating.

At this time Jerome Jr. was nineteen and no longer living at home. He’d managed to graduate from South Niagara High with a vocational arts major and, through Daddy’s intervention, was an apprentice plumber with the contractor for whom Daddy also worked, the largest and best-known plumbing contractor in the city; he had not yet been accepted into the plumbers’ union but there was no doubt that he would be as soon as he completed his probationary period. (No African Americans belonged to the local plumbers’ union. This would be emphasized, unfairly some thought, in the media coverage of the case; unfairly because there were no African Americans in the local police officers’ union, the firefighters’ union, the electricians’ and the carpenters’ unions, among others. The only local union in which black men were welcomed was the sanitation workers’ union which was predominantly black and Latino.) Lionel was sixteen, a sophomore at the high school, big for his age, coarse-skinned, easily bored. Even in vocational arts Lionel’s grades were poor, he cut classes often, our mother didn’t dare report him to our father for fear of a terrible scene. But Lionel was in awe of his independent older brother who lived by himself now in a place near the railroad yard and owned a car, Daddy’s old 1984 Chevrolet he’d passed on to Jerr since it was all but worthless as a trade-in. Weekends the two hung out together drinking beer with Jerr’s friends, cruising in Jerr’s car. Jerr had hated school but now he was hating full-time employment even more, being overseen, assessed and judged. Worse, he hated being a plumber’s assistant, actually having to clear toilets of shit, every kind of crap, came close to puking every time he went out.

What their father called fucking real-life. Didn’t know how the hell long he could take this fucking real-life.

At the house Jerr had grown sick of Mom snooping into his life. Overhearing him on the phone. Giving him unwanted advice. Stripping his bed of soiled sheets, picking up his filth-stiffened socks and underwear from the floor to be laundered. Preparing food he was bored with, he’d grown out of eating years ago, had come to hate. Fast-food restaurants were good enough for him, greasy cheeseburgers, heavily salted french fries. Anything that came in a cellophane wrapper strung up in colorful displays at the 7-Eleven, he’d tear open with his teeth in a pretense of rapacity.

When he’d broken up with his girlfriend boasting how he’d left her stranded at a tavern, exactly what the bitch deserved for disrespecting him, there was Mom shocked and demanding to know why he’d do such a thing, she had met Abbie and Abbie seemed like a nice girl, and Jerr came back at her, “Fuck ‘Abbie is a nice girl.’ You don’t know shit about ‘Abbie,’ Mom. So mind your own fucking business. There’s no ‘nice girls’ just different kinds of pigs.”

Mom was so shocked by Jerr speaking to her in such a way, not just the disrespect, the insolence, but also the meaning of his words, the loathing for her, she could not reply but stumbled away to another room.

No nice girls just different kinds of pigs.

AGAIN AND AGAIN, WHY.

But it was like nice girls, pigs—there was no why.

You would say, the Kerrigan boys had not been brought up that way, and that would be true. And yet.

Going back to a time when our father had attended South Niagara High there’d been incidents involving white boys and darker-skinned boys, especially following Friday night sports events, but these were usually squabbles or altercations between sports teams, rival schools. Rivalry with Niagara Falls High, Tonawanda High, South Buffalo. Some of these teams were predominantly white, and others were predominantly black. South Niagara had integrated teams, our coaches liked to boast. Boys’ teams, girls’ teams. Football, basketball, softball. Swim team.

Cheerleaders? That was another story.

No incident had involved Hadrian Johnson, who was on both the varsity basketball and softball teams in his junior year.

The previous year, when Jerome Kerrigan Jr. had been a senior, he’d known Hadrian Johnson slightly, as he’d known a scattering of African American boys at the school, but there’d been no animosity between them—none at all. So Jerome Jr. insisted, and so it seemed to be true.

Lionel would deny “animosity” too. Any “race prejudice”—not him.

They would insist, they admired black athletes—Mike Tyson, Magic Johnson, Michael Jordan. Jerry Rice, Barry Sanders. And many others.

They’d been aware of Hadrian Johnson on the high school sports teams for who had not been aware of Hadrian Johnson? Not that Hadrian was a brilliant player, usually he was just very good, very reliable, the kind coaches can depend upon.

Yes it was true, the better black athletes at South Niagara were generally showy, spectacular. They modeled themselves after the great national black athletes whom Americans watched avidly on TV. These were the insolent blacks whom white boys feared, disliked, envied. If these black athletes were not demonstrably superior to the very best white players they were likely not to be chosen for varsity teams for there was much pressure from (white) fathers, that their sons be chosen for teams, and there was (as coaches tried to explain) limited space on the teams; but, granted this fact, in the face of such competition still Hadrian Johnson was chosen for two varsity teams, a favorite of coaches and of teammates.

A black kid, yes. But not, you know—one of them.

South Niagara wasn’t a large school: fewer than five hundred students distributed among three grades. In some way everyone knew everyone else.

But white students and darker-skinned students didn’t mix much. On sports teams and in the school band and chorus, service clubs, but not socially.

Nor was there “mixed” dating. Just about never.

It was ironic, Hadrian Johnson had been an outstanding player on the South Niagara Jaycee boys’ softball team, which was comprised of boys from several city schools. Photographs of Hadrian in his Jaycee uniform, to be published in newspapers and on TV, had been taken at Kerrigan Field.

Questioned by South Niagara prosecutors whether they’d had any special reason to stalk and harass Hadrian Johnson, the boys insisted no.

They had not “stalked” him—that was wrong. They’d meant just to scare him. And they had not known it was him—they hadn’t seen his face, not at first.

But had they forced Hadrian Johnson off the road, because he was black?

Vehemently they denied this. Repeatedly, they denied this.

Four white boys driving a vehicle, a solitary black boy on a bicycle, late Saturday night—but no, they were not racists.

It would be bitterly debated, whether the attack had been a hate crime, or an assault that had gotten out of control in which race wasn’t an issue. If a hate crime the assailants were likely to be sentenced to longer prison sentences, if they were found guilty; but there was the possibility, if they insisted upon a jury trial, that they might be acquitted by a sympathetic (i.e., white) jury. If he could devise a way in which such a defense would not backfire and make things worse, in the media for instance, their lawyer was considering the boys might claim self-defense.

The boys had been drinking for most of the evening. Two of them were underage which involved the others, for having supplied them with alcohol; the 7-Eleven storekeeper who’d sold them the six-packs was in trouble as well. They’d been driving around, at the mall, returned from the mall, drinking and tossing beer cans. Stopped at Friday’s, where there was a crowded bar scene, later at Cristo’s (which was taking a chance, our father sometimes dropped by Cristo’s on Friday night). Past Kerrigan Field. Past Patriot Park. Kirkland Avenue, Depot Street, Delahunt. Saw this guy in a hoodie riding a bicycle on Delahunt looking kind of suspicious to us like he didn’t belong in the neighborhood. Something in the bicycle basket looked like could be stolen goods. We did not see his face—we did not know who it was … If they’d shouted after him it was just a way of talking, scaring someone who (maybe) didn’t belong in the place he was in. If Jerr aimed the car at the bicyclist it was just to scare him not to run him down at the side of the road.

And the way he tried to escape crawling away, yelling to leave him alone. Like what a guilty person would do.

Like cops, they were. Neighborhood “vigilantes.” Keeping strangers from breaking into houses, stealing cars.

Their lawyers were suggesting this possibility. “Vigilantes”?—“fighting crime”? Like the possibility of self-defense.

Problem was, the boys weren’t in their own neighborhood. Hadrian Johnson happened to be in his neighborhood.

Yes but they hadn’t known. Like they hadn’t gotten a look at their victim’s face until—later.

Delahunt was a darkened road at this time of night. Strip mall, fast-food taco place, gas station. At Seventh Street there was a small trailer court with a string of unlit lights, from the previous Christmas. Beyond that a potholed street of small wood frame bungalows lacking a sidewalk, called Howard.

Following the bicyclist along Delahunt. For the hell of it.

Well—who rides a bicycle at night? Looked like a tall dude, not a kid. Not a young kid. And what was in the basket?

Reflectors on the back of the bike and the bike looked (they could see, squinting in headlights) like it might be pretty expensive. Stolen merchandise?

The bicyclist was acting guilty, they thought. Bumping along on the shoulder of the road. Knew they were there, and coming close to him. Maybe he thought they were cops. So he tried to pedal faster, fast as he could, intending to turn into a dirt lane opening ahead in a field, looking to escape. For whoever was in the car was coming close to him, honking his horn like machine-gun fire. Guys yelling out the windows.

It would turn out that Hadrian Johnson had spent the evening at his grandmother’s house on Amsterdam Street a mile away. Sometimes when Hadrian spent time with his grandmother who suffered from diabetes he stayed the night but this night, he did not. Bicycling home to Howard Street along a stretch of Delahunt where if there was traffic it was likely to be fast but there was relatively little traffic at that hour of the night, he’d been ten minutes from his mother’s house when a vehicle had come up swiftly behind him swamping him with its bright lights, deafening horn, derisive shouts, curses.

Thud of the front right fender striking the bicycle, a high-pitched scream, the fallen boy amid the twisted bicycle trying to free himself and crawl away …

What happened next was confused.

Hard to remember. Like something smashed and broken, you are trying to reassemble.

Still it was an accident. The boys would claim. Had to be, for what happened hadn’t been premeditated.

Striking the bicyclist, could see by this time that it was a kid, (maybe) a black kid, but (still, yet) no one they recognized, so Jerr braked the car to a stop, had to check the bicyclist to see if he was all right …

True Jerr did stop the car. True they did exit the car.

True they did approach the (injured?) boy who was trying to crawl away from them at the side of the road …

(Was it true, all four boys had exited the Chevrolet? Or had Walt remained inside, as Walt would never cease to claim?)

Here is a fact: nothing of what happened was what Jerome, Lionel, Walt, Don had meant to happen. Which wasn’t to say that they remembered clearly what had happened.

Just that they’d been drinking. The older guys had gotten the beer for the younger guys. Saturday night. Deserving more from fucking Saturday night. Not ready to go fucking home just yet.

But only seconds, they’d stopped on Delahunt. Not even a minute—they were sure. Vaguely aware of traffic on the road, a vehicle passing. Someone slowing to call out the window What’s going on? and Jerr yelling back We called 911, it’s OK.

And then panicked and back in the Chevrolet. Driving away with squealing tires like a TV cop show. And even then they would (afterward) claim they’d scarcely been aware that the badly injured bicyclist was dark-skinned, still less his identity: seventeen-year-old Hadrian Johnson from their own school.

SHORTLY AFTER MIDNIGHT OF NOVEMBER 2, 1991, AN ANONYMOUS call was placed to 911 reporting a badly beaten young man lying unconscious and unresponsive at the side of Delahunt Road, South Niagara, a bicycle twisted beside him. An emergency medical team from South Niagara General Hospital was immediately dispatched and the stricken young man brought back, by ambulance, still unconscious and unresponsive, to the ER.

The victim would never regain consciousness but would die, of severe brain damage and other traumatic injuries, nine days later.

No other calls to 911 had been reported that night. But the following morning when news of the beating began to spread through South Niagara an anonymous caller reported to police that he’d been driving on Delahunt Road the night before, around 11:40 P.M., when he’d seen a vehicle parked at the side of the road, where someone, it appeared to be a young black man, was lying on the ground bleeding from a head wound as four or five “young white guys” stood around him. It had looked, the caller said, as if there’d been a fight. He’d slowed his pickup then accelerated when the white guys saw him for they were looking “threatening”—“drunk and scared”—and he’d thought he saw one of them with a rifle.

Maybe not a rifle. A tire iron? Baseball bat?

He’d gotten out of there, fast. Hoping to hell they wouldn’t get in their car and follow him.

The caller went on to identify the car as a mid-1980s model Chevy, dull bronze, pretty battered, rusted, and dented—“Especially, you could see that the front right fender was bent all in from where they’d hit the kid. You couldn’t miss that.”

He hadn’t gotten a good look at the boys. Just “white kids”—“maybe high school age, or a little older”—but he’d tried to memorize the license plate number: “first three digits—KR4—something like that.”

Louisville Slugger (#ulink_9c795d09-1a90-532d-a908-ebfd7e79b940)

IF THE FUCKING BAT HADN’T BEEN THERE.

Because none of it had been premeditated. Because it had just happened—the way fire just happens.

Because it had been rattling in the back of the car, for months. Why’d he carry the bat loose in the car he’d liked to say For protection.

Sort of, he meant it. But it was a kind of joke too.

Because most things, fucking things in his fucking life, were jokes. Which included the bat.

Just his old baseball bat. The label worn off, he’d had for years. Couldn’t remember when he’d played baseball last. But the bat was his—his brothers had to have their own damn bats if they had a bat at all.

Never thought about it. Not much.

Rattling in the back of the car along with some empty beer cans and other shit, he’d stopped hearing.

Except that night, one of the (drunk) guys in the back snatched it up. And outside, in the confusion, he grabbed it away from whoever it was, maybe Don Brinkhaus, excited and aroused and swinging the bat because the bat was his and the bat was fucking wonderful, the solid grip, the weight of it, soiled old black tape he’d wound around the handle how many years ago. He’d never been a great batter, but he was OK. Easily embarrassed and discouraged and fucking disgusted, missing easy pitches, striking the ball not hard enough so it popped up like a little kid might pop it, fell straight down, rolled at the first baseman’s feet … Wanting to murder any asshole who laughed at him.

But now, no. Fucking bat wasn’t missing its target now.

Black kid sprawled on the ground pleading with them to let him go, please let him go, bleeding from his nose and mouth not so hot-shit now. Flat on his back and begging. And the guys jeering, laughing. Swatting at him, kicking.

Like he’d provoked them to run into him. Dented the fender of the fucking car, because of him.

Natural in Jerr’s hands for the bat to rouse itself to life, and get away from him. Furious, fast. Like chopping wood.

The crack! of the bat. Or was it the crack! of the skull.

But without the bat, maybe not. No.

Wouldn’t have cracked the skull. And all the blood.

Without the fucking bat would’ve kicked the black kid a few more times then let him go. Seeing he wasn’t fighting back, had gone limp. Probably not able to identify them, his eyes are swollen shut. Blood all over his face. What the fuck. Nobody wanted to kill anybody, that was a fact.

That was a fact. They’d swear on the Bible.

Came to him they’d (maybe) mixed this kid up with another black kid, a bigger kid, heavier, older by a year or two. Football player—“tight end.” With the bleached-blond white girlfriend. Hanging out across the street from school. That motherfucker, they’d have meant to stomp, wipe the smirk off his fat face.

Except for the bat. Fucking bat. None of it would have happened. Or in the way it happened. You could argue it was mitigating circumstances. How the bat came to be in Jerr’s hands at just that minute.

Because it hadn’t been premeditated, bringing the bat. Just in the back of the car where it had been rolling around for months. And so, like an accident. Christ sake it was an accident.

And maybe also, could they argue they’d been drinking, and their judgment was off. Buying six-packs and nobody asking them who it was for, how old. None of it would’ve happened except for that. Which wasn’t their fault—there were adults to blame. And the car, his father had given him. Christ! He hadn’t even asked for it, he’d known better than to ask his father would’ve made him crawl, if he had. Surprising the hell out of him, just giving him the car which would have been worth something at least, a few hundred at least, on a trade-in. But he’d given Jerr the car, which put Jerr in his debt big-time. And made Jerr anxious, taking care of it. Every time he came to the house the old man would go out into the driveway and inspect the car and if he didn’t say anything that could be worse than if he did for at least, if he did, you’d know what he was thinking. And Jerome Kerrigan was always fucking thinking.

Which led to Jerr swerving the damned car off the road. Like wanting to get rid of it. A few beers, you started thinking that way. Hitting the black kid was just collateral damage. You could argue that was an accident, nobody’d known the kid was even there until they saw him. He’d been meaning just to scare the kid, make the guys laugh, impress his brother who thought he was a cool dude but the front wheels hit gravel and swerved, right front fender struck the kid and lifted him, and the God-damned bicycle leaving a dent in the fender him and Lionel would have to try to even out with their bare hands, panting and struggling to unbend it but still the dent is there. Fucking rust on their fingers.

And blood from the bat, they’d have to scrub like hell.

Chain of circumstances, accidents. Could happen to anyone.

None of it premeditated. That’s the crucial point.

Realizing then, his father had given him the fucking baseball bat. Sure. That’s who it was, had to be, making a big deal of it, bringing him to the store downtown to pick it out for his birthday: Louisville Slugger. The best.

Now you got to live up to it, kid.

The Little Sister (#ulink_a7516be0-4eaa-5d1d-84c3-0b4d7fa1902d)

WAKENED BY—SOMETHING …

Not a flash of headlights on the wall of the darkened room. Not the expansion of headlights on two walls of our room, if a vehicle turned into our driveway.

So that I would think, but only later—They cut the headlights. Not wanting to wake anyone.

Still less would I think, at the age of twelve—This part of it would be premeditated. Leaving nothing to chance.

And so I saw the time: 12:25 A.M. Someone had entered the kitchen downstairs, from the rear of the house, through the garage. I did not yet know that it was Jerr and Lionel.

Though Jerr had his own place to live now often he turned up at our house. He’d brought Lionel home, but wasn’t leaving immediately. He’d dropped the others, our cousin Walt, and Don Brinkhaus, at their houses.

At this time they had not known, they would claim they’d had no idea, that Hadrian Johnson had been beaten so badly he would never regain consciousness.

Though bleeding badly from head wounds, from the blows of Jerr’s baseball bat, they would claim that, when they’d left him, Hadrian Johnson had looked as if he was all right.