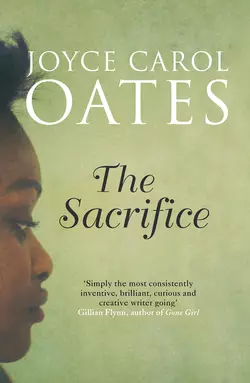

The Sacrifice

Joyce Carol Oates

‘Simply the most consistently inventive, brilliant, curious and creative writer going’ Gillian FlynnBest-selling author Joyce Carol Oates blends sexual violence, racism, brutality, and power in her latest incendiary novel.Best-selling author Joyce Carol Oates returns with an incendiary novel that illuminates the tragic impact of sexual violence, racism, brutality, and power on innocent lives and probes the persistence of stereotypes, the nature of revenge, the complexities of truth, and our insatiable hunger for sensationalism.When a fourteen-year-old girl is the alleged victim of a terrible act of racial violence, the incident shocks and galvanises her community, exacerbating the racial tension that has been simmering in this New Jersey town for decades. In this magisterial work of fiction, Joyce Carol Oates explores the uneasy fault lines in a racially troubled society. In such a tense, charged atmosphere, Oates reveals that there must always be a sacrifice – of innocence, truth, trust, and, ultimately, of lives. Unfolding in a succession of multiracial voices, in a community transfixed by this alleged crime and the spectacle unfolding around it, this profound novel exposes what – and who – the “sacrifice” actually is, and what consequences these kind of events hold for us all.Working at the height of her powers, Oates offers a sympathetic portrait of the young girl and her mother, and challenges our expectations and beliefs about our society, our biases, and ourselves. As the chorus of its voices – from the police to the media to the victim and her family – reaches a crescendo, “The Sacrifice” offers a shocking new understanding of power and oppression, innocence and guilt, truth and sensationalism, justice and retribution.A chilling exploration of complex social, political, and moral themes – the enduring trauma of the past, modern racial and class tensions, the power of secrets, and the primal decisions we all make to protect those we love – “The Sacrifice” is a major work of fiction from one of our most revered literary masters.

Copyright (#ulink_5057c24a-559d-506a-8011-18708bf0a1cd)

Fourth Estate

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.4thestate.co.uk (http://www.4thestate.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain by Fourth Estate in 2015

First published in the United States by Ecco in 2015

Copyright © The Ontario Review 2015

Joyce Carol Oates asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

Cover photograph © Nagib El Desouky / Arcangel Images.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Find out about HarperCollins and the environment at

www.harpercollins.co.uk/green (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk/green)

Source ISBN: 9780008114862

Ebook Edition © January 2015 ISBN: 9780008114879

Version: 2015-10-13

Dedication (#ulink_17bb8516-6e0e-5f4e-9a5f-f2618f0ddef6)

for Richard Levao

and for Charlie Gross

Contents

Cover (#u34761eb3-266d-508c-827b-67ac0f202d5b)

Title Page (#uca45bb0c-148c-55d2-92ab-aa6ba68f4b82)

Copyright (#u3e0bbf4e-7c99-504d-aaaa-3cb79809047e)

Dedication (#udb78d89e-8915-5f60-bbbc-c33251439254)

The Mother (#u78693cce-9f90-5d37-8719-04e99797a84f)

The Discovery (#ue5cfadff-6e40-520f-8164-77cb303d0fae)

“White Cop” (#ubc93ea67-fc54-5832-bf35-3173131531ac)

St. Anne’s Emergency (#u66a2ff0d-86e6-5bde-a60e-3f7f13cea4fd)

The Interview (#ueab3be8b-1368-5ad8-b3ac-569b7f230ed3)

Red Rock (#ud4e2661f-1235-5e2a-b283-345a04d0b48c)

“S’quest’d” (#u01ed6856-ee44-51cc-9fc5-29e228bc66d0)

Girl-Cousins (#u59ec89b6-0a0a-52a8-aedf-7bd715f6941f)

The Investigator (#litres_trial_promo)

Angel of Wrath (#litres_trial_promo)

The Good Neighbor (#litres_trial_promo)

The Lucky Man (#litres_trial_promo)

The Stepdaughter (#litres_trial_promo)

The Mission (#litres_trial_promo)

The Temptation (#litres_trial_promo)

The Seduction (#litres_trial_promo)

The Crusade (#litres_trial_promo)

“Nazi-Racist Swine” (#litres_trial_promo)

“Reassigned” (#litres_trial_promo)

The Good Son (#litres_trial_promo)

The Twins (#litres_trial_promo)

Safe House (#litres_trial_promo)

“Yelow Hair” (#litres_trial_promo)

The Prize (#litres_trial_promo)

The Crusade (#litres_trial_promo)

The Martyr (#litres_trial_promo)

The Broken Doll (#litres_trial_promo)

The Convert (#litres_trial_promo)

The Sisters (#litres_trial_promo)

“Still Alive” (#litres_trial_promo)

Ten-Thousand-Man March (#litres_trial_promo)

Afterword (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

Novels by Joyce Carol Oates (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

The Mother (#ulink_cb4c8916-ca2f-5373-8078-1f41bda404f9)

OCTOBER 6, 1987

PASCAYNE, NEW JERSEY

Seen my girl? My baby?

She came like a procession of voices though she was but a singular voice. She came along Camden Avenue in the Red Rock neighborhood of inner-city Pascayne, twelve tight-compressed blocks between the New Jersey Turnpike and the Passaic River. In the sinister shadow of the high-looming Pitcairn Memorial Bridge she came. Like an Old Testament mother she came seeking her lost child. On foot she came, a careening figure, clumsy with urgency, a crimson scarf tied about her head in evident haste and her clothing loose about her fleshy waistless body. On Depp, Washburn, Barnegat, and Crater streets she was variously sighted by people who recognized her face but could not have said her name as by people who knew her as Ednetta—Ednetta Frye—who was one of Anis Schutt’s women, but most of them could not have said whether Anis Schutt was living with this middle-aged woman any longer, or if he’d ever been living with her. She was sighted by strangers who knew nothing of Ednetta Frye or Anis Schutt but were brought to a dead stop by the yearning in the woman’s face, the pleading in her eyes and her low throaty quavering voice—Any of you seen my girl S’b’lla?

It was midmorning of a white-glaring overcast day smelling of the Passaic River—a sweetly chemical odor with a harsh acidity of rot beneath. It was midmorning following a night of hammering rain, everywhere on broken pavement puddles lay glittering like foil.

My girl S’b’lla—anybody seen her?

The anxious mother had photographs to show the (startled, mostly sympathetic) individuals to whom she spoke by what appeared to be purest chance: pictures of a dark-skinned girl, bright-eyed, a slight cast to her left eye, with a childish gat-toothed smile. In some of the photos the girl might have been as young as eleven or twelve, in the more recent she appeared to be about fourteen. The girl’s dark hair was thick and stiff and springy, lifting from her puckered forehead and tied with a bright-colored scarf. Her eyes were shiny-dark and thick-lashed, almond-shaped like her mother’s.

S’b’lla young for her age, and trustin—she smile at just about anybody.

In Jubilee Hair Salon, in Ruby’s Nails, in Jax Rib Joint, and the Korean grocery; in Liberty Bail & Bond, in Scully’s Pawn Shop, in Pascayne Veterans Thrift Shop, in Passaic County Family Ser vices and in the crowded cafeteria of the James J. Polk Memorial Medical Clinic as in windswept Hicks Square and several graffiti-defaced bus-stop shelters on Camden there came Ednetta Frye breathless and eager to ask if anyone had seen her daughter and to show the photographs spread in her shaky fingers like playing cards—You seen S’b’lla? Yes maybe? No?

She grasped at arms, to steady herself. She appeared dazed, disoriented. Her clothes were disheveled. The scarf tying back her stiff-oiled hair was askew. On her feet, waterstained sneakers beginning to fray at each outermost small toe with a quaint symmetry.

Since Thu’sday she been missin. Day and a night and a nother day and a night and most this time I was thinkin she be with her cousin Martine on Ninth Street comin there after school like she do sometimes and she forgot to call me, so I—I was just thinkin—that’s where she was. But now they sayin she ain’t there and at her school they sayin she never showed up Thu’sday and there be other times she’d cut since September when the school started that wasn’t known to me and now don’t nobody seem to know where my baby is. Anybody see S’b’lla, please call me—Ednetta Frye. My telephone is …

Her beautiful eyes mute with suffering and veined with broken capillaries. Her skin the dark-warm-burnished hue of mahogany. There was an oily sheen to her face, that glared in the whitely overcast air. From a short distance Ednetta appeared heavyset with large drooping breasts like water-sacks, wide hips and thighs, yet she wasn’t fat but rather stout and rubbery-solid, strong, resistant and even defiant; of an indeterminate age beyond forty with a girl’s plaintive face inside the puffy face of the aggrieved middle-aged woman.

Please—you sayin you seen her? Ohhh but—when? Since Thu’sday? That’s two days ago and two nights she been missin …

Along wide windy Trenton Avenue there came Ednetta Frye lurching into the Diamond Café, and into the Wig-a-Do Shop, and into AMC Loans & Bail-Bond, and into storefront Goodwill where the manager offered to call 911 for her to report her daughter missing and Ednetta said with a little scream drawing back with a look of anguish No! No po-lice! How’d I know the Pascayne police ain’t the ones taken my girl!

Exiting Goodwill stumbling in the doorway murmuring to herself O God O God don’t let my baby be hurt O God have mercy.

Sighted then making her way past shuttered storefront businesses on Trenton Avenue and then to Penescott to Freund which were blocks of brownstone row houses converted into apartments and so to Port and Sansom which were blocks of small single-story stucco and wood frame bungalows built close to cracked and weed-pierced sidewalks. An observer would think that the distraught woman’s route was haphazard and whimsical following an incalculable logic. Sometimes she crossed the street several times within a single block. There were far fewer people on these residential streets so Ednetta knocked on doors, called into dim-lighted interiors, several times boldly peered into windows and rapped on glass—’Scuse me? Hello? C’n I ask you one thing? This my daughter S’b’lla Frye she missin since Thu’sday—you seen anybody looks like her?

Crossing vacant lots heaped with debris and along muddy alleys whimpering to herself. She’d begun to walk with a limp. She was panting, distracted. She seemed to have taken a wrong turn, but did not want to retrace her steps. Somewhere close by, a dog was barking furiously. Overhead, a plane was descending to Newark International Airport with a deafening roar—Ednetta craned her neck to stare into the sky as at a sign of God, unfathomable and terrible. Here below were abandoned and derelict houses, a decaying sandstone tenement building on Sansom long known as a hangout for drug addicts, teenagers, homeless and the mentally ill which Ednetta Frye approached heedlessly. H’lo? Anybody in here? H’lo! H’lo!

And daring to step into the street to stop vehicles to announce to the startled occupants ’Scuse me! I am Ednetta Frye, this is my daughter S’b’lla Frye, she fourteen years old. Last I seen of S’b’lla she be leavin for school and now they sayin she never got there. This was Thu’sday.

She passed the pictures of Sybilla to these strangers who regarded them somberly, handed them back to Ednetta and assured her no, they hadn’t seen the girl but yes, they would be on the lookout for her.

At Sansom and Fifth there came sharp gusts of wind from the river, fresh-wet air and a sickly-sweet odor of leaves and strewn garbage in the alleys. And there stood Ednetta Frye on the curb pausing to rest like a laborer who is exhausted after an effort that has come to nothing. No one so alone as the bereft mother seeking her lost child in vain. The heel of her hand pressed against her chest as if she were stricken with heart-pain and she was staring into the distance, at the Pitcairn Bridge lifted and spread like a great prehistoric predator-bird and beyond at the slow bleed of the sky and on her face tears shone unabashed, so little awareness had Ednetta of these tears she hadn’t lifted a hand to wipe them away.

THAT POOR WOMAN SHE SCARED OUT OF HER WITS LIKE SHE AIN’T EVENaware who she talkin to!

Primarily it was women. During Ednetta Frye’s several hours of search and inquiry in the Camden Avenue–Twelfth Street neighborhood of inner-city Pascayne on the morning of October 6, 1987.

Some sixty individuals would recall Ednetta, afterward.

Of these a number were women who knew Ednetta Frye from the neighborhood and who’d seen her frequently with children presumed to be hers including the daughter Sybilla—but they hadn’t seen Sybilla within the past forty-eight hours, they were sure.

Of these were women who’d known Ednetta Frye for years—as long as thirty, thirty-five years—when they’d been girls together in the old Roosevelt projects, long since condemned and razed and replaced by a never-completed riverfront “esplanade” that was a quarter-mile sprawl of concrete and mud, rusted chain-link fences, frayed flapping plastic signs danger do not enter construction. They’d gone to East Edson Elementary in the 1950s and on to East Edson Middle School and to Pascayne South High. Some of them had known Ednetta when she’d been a young mother—(she’d had her first baby at sixteen, forced to quit school and never returned)—and during those years when she’d worked part-time as a nurse’s aide at the Polk clinic taking the Clinton Street bus along Camden Avenue, a husky straight-backed good-looking woman with a gat-toothed smile, warm-rippling laughter that made you want to laugh with her.

And there were those who’d known Ednetta in the past decade or so since she’d been living with Anis Schutt in one of the row house brownstones on Third Street. Some of these women who’d known Anis Schutt when he’d been incarcerated at Rahway maximum-security and before that at the time of Anis’s first wife’s death—“manslaughter” was the charge Anis had pleaded to—had (maybe) wondered at Ednetta who was younger than Anis by at least ten years falling in love with such a man, taking such a risk, and her with three young children.

Ednetta had always belonged to the AME Zion Church on First Street.

She’d sung in the choir there. Rich deep contralto voice like Marian Anderson, she’d been told.

Good-looking as Kathleen Battle, she’d been told.

Never missed church. Sunday mornings with her mother and her grandmother (her old ailing grandmother she’d helped nurse) and her aunts and her girls Sybilla and Evanda, Ednetta’s happiest times you could see in her face.

Anis Schutt never came to the AME Zion Church. No man leastway resembling Anis Schutt was likely to come to the AME Zion Church where the shock-white-haired minister Reverend Clarence Denis frequently preached himself into a frenzy of passion and indignation on the subject of “taking back” Red Rock from the “thugs and gangsters” who’d stolen it from the good black Christian people.

A few years ago there’d been a rumor of Ednetta Frye fired from the Polk clinic for (maybe) stealing drugs. Ednetta Frye charged with “bad checks” when it was claimed by her that she’d been the victim. Ednetta working at Walmart—or Home Depot—one of those big-box stores at the Pascayne East Mall where you were lucky to get minimum wage and next-to-no health benefits but you could buy damaged and outdated merchandise cheap which all the employees did especially at back-to-school and Christmas time.

Over the years there’d been rumors of ill health: diabetes? arthritis? (Seeing how Ednetta had put on weight, fifty pounds at least.) Taking the children to relatives’ homes to hide from Anis Schutt in one of his bad drunk moods but Ednetta had not ever called 911 and had not ever fled to St. Theresa’s Women’s Shelter on Twelfth Street as other women (including her younger sister Cheryl) had done at one time or another nor had she gone to Passaic County Family Court to ask for an injunction to keep Anis Schutt at a distance from her and the children.

Ednetta Frye, who loved her children. Who did most of the work raising Anis Schutt’s several children (from his only marriage, with the wife Tana who’d died) along with her own—five or six of them in the cramped household though Anis’s boys being older hadn’t remained long.

One of the sons at age nineteen shot dead on a Newark street in a drive-by fusillade of bullets.

Another son at age twenty-three incarcerated at Rahway on charges of drug-dealing and aggravated assault, twelve to twenty years.

They were an endangered species—black boys. Ages twelve to twenty-five, you had to fear for their lives in inner-city Pascayne, New Jersey.

Ednetta had a son, too—ten years old. And another, younger daughter, Sybilla’s half-sister.

Of the women to whom Ednetta Frye showed Sybilla’s picture this morning several knew Anis Schutt “well” and at least two of them—(Lucille Hersh, Marlena Swann)—had had what you’d call “relations” with the man, years before.

Lucille’s twenty-year-old son Rodrick was Anis’s son, no doubt about that. Marlena’s eight-year-old daughter Angelina was Anis’s daughter, he’d never contested it. Exactly how many other children Anis had fathered wasn’t clear. He’d started young, as Anis said, laughing—hadn’t had time for counting.

It was painful to Ednetta of course—running into these women. Seeing these women cut their eyes at her.

Worse, seeing these women with children the rumor was, Anis was the father. That was nasty.

You could see that poor woman scared out of her wits like she ain’t even aware who she talking to. I saw it myself, Ednetta come up to me an my friend Jewel in the grocery like she never knew who we were—Ednetta Frye be Jewel’s enemy on account of Anis who ain’t done shit to help Jewel out, all the time he promise he would. And Ednetta looks at us with like these blind eyes sayin ’Scuse me! Hopin you can help me! My daughter S’b’lla—you seen her?

That big girl gone only a day or two and Ednetta was actin like the girl be dead, we thought it was kind of exaggerated but when you’re a mother, you do worry. And when a girl is that age like S’b’lla, you can’t trust her.

You wouldn’t ask Ednetta if she’d called the police, knowin how Anis feel about police and how police feel about Anis.

So we said to her, we will look for S’b’lla for sure! We will ask about her, everyone we know, and if we see her, or learn of her, we will inform Ednetta right away.

And she was cryin then, she like to hugged us hard and she say, Thank you! And God bless you, I am praying He will bless me and my baby and spare her from harm.

And we stand there watchin that poor woman walk away like she be drunk or somethin, like she be walkin in her sleep, and we’re sayin to each other what you say at such a time when nobody else can hear—Poor Ednetta Frye, sure am happy I ain’t her!

The Discovery (#ulink_3687cb31-50a6-5f22-a0e9-67183a859983)

OCTOBER 7, 1987

EAST VENTOR AT DEPP

PASCAYNE, NEW JERSEY

You hear that? That like cryin sound?”

In the night she’d heard it, whatever it was—had to hope it wasn’t what it might be.

Might be a trapped bird, or animal—not a baby … She didn’t want to think it might be a baby.

A soft-wailing whimpering sound. It rose, and it fell—confused with her sleep which was a thin jittery sleep to be pierced by a sliver of light, or a sliver of sound. Those swift dreams that pass before your eyes like colored shadows on a wall. And mixed with night-noises—sirens, car motors, barking dogs, shouts. The worst was hearing gunshots, and screams. And waiting to hear what came next.

She’d lived in this neighborhood of Red Rock all of her life which was thirty-one years. Bounded by the elevated roadway of the New Jersey Turnpike some twelve blocks from the river, and four blocks wide: Camden Avenue, Crater, East Ventor, Barnegat. Following the “riot” of August 1967—(riot was a white word, a police word, a word of reproach and judgment you saw in headlines)—Red Rock had become a kind of inner-city island, long stretches of burnt-out houses, boarded-up and abandoned buildings, potholed streets and decaying sidewalks and virtually every face you saw was dark-skinned where you might recall—(Ada recalled, as a child)—you’d once seen a mix of skin tones as you’d once seen stores and businesses on Camden Avenue.

She’d gone to Edson Elementary just up the block. She’d taken a bus to the high school at Packett and Twelfth where she’d graduated with a business degree and where for a while she’d had a job in the school office—typist, file clerk. There were (white) teachers who’d encouraged her to get another degree and so she’d gone to Passaic County Community College to get a degree in English education which qualified her for teaching in New Jersey public schools where sometimes she did teach, though only as a sub. There was prejudice against community-college teacher-degrees, she’d learned. A prejudice in favor of hiring teachers with degrees from the superior Rutgers education school which meant, much of the time, though not all of the time, white or distinctly light-skinned teachers. Ada didn’t want to think it was a particular prejudice against her.

She’d lain awake in the night hearing the faint cries thinking it was probably just a bird trapped in an air shaft. This old tenement building, five floors, no telling what was contained within the red-brick walls or in the cellar that flooded in heavy rainfall when the Passaic overflowed its banks and sewage rushed through the gutters. A pigeon with a broken wing, that had flung itself against a windowpane. A stray dog that had wandered into the building smelling food or the possibility of food and had gotten trapped somewhere when a door blew shut.

“Nah I don’t hear nothin’. Aint hearin anything.”

“Right now. Hear? It’s somebody hurt, maybe …”

“Some junkie or junkie-ho’. No fuckin way we gonna get involved, Ada. You get back here.”

Ada laughed sharply. Ada detached her mother’s fingers from her wrist. She was a take-charge kind of person. Her teachers had always praised her and now she was a teacher herself, she would take charge. She wasn’t the kind of person to ignore somebody crying for help practically beneath her window.

Down the steep creaking steps with the swaying banister she was having second thoughts. In this neighborhood even on Sunday morning you could poke your nose into something you’d regret. Ma was probably right: drug dealers, drug users, kids high on crack, hookers and homeless people, somebody with a mental illness …

She couldn’t hear the cries now. Only in her bedroom had she really heard, distinctly.

Years ago the factory next-door had been a canning factory—Jersey Foods. Truckloads of fish gutted and cooked and processed into a kind of mash, heavily salted, packed into cans. And the cans swept along the assembly line, and loaded into the backs of trucks. Tons of fish, a pervading stink of fish, almost unbearable in the heat of New Jersey summers.

Jersey Foods had been shut down in 1979 by the State Board of Health. The derelict old building was partially collapsed, following a fire of “suspicious origin”; its several acres of property, including an asphalt parking lot with cracks wide as crevices, as well as the rust-colored building, lay behind a six-foot chain-link fence that was itself badly rusted and partially collapsed. Signs warning no TRESPASSING had not deterred neighborhood children from crawling through the fence and playing in the factory despite adults’ warnings of danger.

In the other direction, on the far side of the dead end of Depp Street, was another shuttered factory. Even more than Jersey Foods, United Plastics was off-limits to trespassers for the poisons steeped in its soil.

You’d think no one would be living in this dead-end part of Pascayne—but rents were cheap here. And no part of inner-city Pascayne was what you’d call safe.

It was Ada’s hope to be offered a full-time teacher’s job in an outlying school district in the city, or in one of the suburbs. (All of the suburbs were predominantly white but “integrated” for those who could afford to live there.) Then, she’d move her family out of squalid East Ventor.

Six years she’d been hoping and she hadn’t given up yet.

“God! Don’t let it be no baby.”

(Well—it wouldn’t be the first time a baby had been abandoned in this run-down neighborhood by the river. Dead-end streets, shut-up warehouses and factories, trash spilling out of Dumpsters. Some weeks there wasn’t any garbage pickup. A heavy rain, there came flooding from the river, filthy smelly water in cellars, rushing along the gutters and in the streets. Walking to the Camden Street bus Ada would see rats boldly rooting in trash just a few feet away from her ankles. [She had a particular fear of rats biting her ankles and she’d get rabies.] Nasty things fearless of Ada as they were indifferent to human beings generally except for boys who pelted them with rocks, chased and killed them if they could. And what the rats might be dragging around, squeaking and eating and their hairless prehensile tails uplifted in some perky way like a dog, you didn’t want to know. For sure, Ada didn’t want to know. Terrible story she’d heard as a girl, rats devouring some poor little baby left in some alley to die. And nobody would reveal whose baby it was though some folks must’ve known. Or who left the baby in such a place. And the white cops for sure didn’t give a damn or even Family Services and for years Ada had liked to make herself sick and scared in weak moods thinking of rats devouring a baby and so, whenever she saw rats quickly she turned her eyes away.)

Ada was uneasy remembering Ednetta Frye from the previous morning. She’d seen the distraught woman first crossing Camden Avenue scarcely aware of traffic, then in the Korean grocery, then approaching people in Hicks Square who stared at her as you’d stare at a crazy person. Ednetta had seemed so distracted and disoriented and frightened, nothing like her usual self you could talk and laugh with—it was Ednetta who did most of the talking and the laughing at such times. There’d been occasions when Ednetta had a bruised face and a swollen lip but she’d laugh saying she’d walked into some damn door. You guessed it had to be Anis Schutt shoving the woman around but it wasn’t anything extreme, the way Ednetta laughed about it.

Ada was at least ten years younger than Ednetta Frye. She’d substitute-taught at the middle school when Ednetta’s daughter Sybilla had been a student there, a year or two ago; she knew the Fryes from the neighborhood, though not well.

They were neighbors, you could say. East Ventor crossed Crater and if you took the alley back of Crater to Third Street, somewhere right around there Ednetta was living in one of the row houses with that man and her children—how many children, Ada had no idea.

With her education degree and New Jersey teacher’s certificate Ada Furst liked to think that there was something like a pane of glass between herself and people like the Fryes—it might be transparent, but it was substantial.

But the day before, Ednetta hadn’t been in a laughing or careless mood. She’d been anxious and frightened. She’d showed Ada photos of Sybilla as if Ada didn’t know what Sybilla looked like—Ada had had to protest, “Ednetta, I know what Sybilla looks like! Why’re you showing me these?”

Ednetta hadn’t known how to answer this. Stared at Ada with blank slow-blinking eyes as if she hadn’t recognized Ada Furst the schoolteacher.

“She’s probably with some friends, Ednetta. You know how girls are at that age, they just don’t think.”

Ednetta said, “S’b’lla know better. She been brought up better. If Anis get disgusted with her, he goin to discipline her—serious. S’b’lla know that.”

Ada said another time that Sybilla was probably with some friends. Ednetta shouldn’t be worried, just yet.

“I don’t know how long you’d be wantin me to wait, to be ‘worried,’” Ednetta said sharply. “I told you, Anis don’t allow disrespectful behavior in our house. S’b’lla got to know that.”

Clutching her photographs Ednetta moved on. Ada watched the woman pityingly as she approached people on the street, imploring them, practically begging them, showing the pictures of Sybilla. Most people acted polite, and some were genuinely sympathetic. There was something not right about what Ednetta was doing, Ada thought. But she had no idea what it was.

Ada was ashamed now, she’d spoken so inanely to Ednetta Frye. But what did you say? Girls like Sybilla were always “running away”—Ada knew from being a schoolteacher—meaning they were staying with some man likely to be a dozen years older than they were, and giving them drugs. What she could remember of Sybilla Frye from the middle school, the girl was sassy and impudent, restless, couldn’t sit still to concentrate, had a dirty mouth to her, and hung out with the wrong kind of girls. Her grades were poor, she’d be caught with her friends smoking out the back door of the school—in seventh grade. None of that could Ada tell poor Ednetta!

Ada knocked at the second-floor door of a woman named Klariss—just a thought, she’d ask Klariss to come with her. But Klariss was as vehement as Ada’s mother. “You keep outa that, Ada. You know it’s some drug dealer somebody put a bullet in, or some druggie OD’ing. You get mixed up in it, the cops is gonna mix you up with them and take you all in.”

Weakly Ada tried to cajole Klariss into at least coming outside with her, in back of the building—“You don’t have to come any farther, K’riss. Just, like—see if anything happens …”

But Klariss was shutting her door.

In the front vestibule were several tall teenaged boys on their way outside—ebony-black skin, mirthful glances exchanged that signaled their awareness of / disdain for stiff-backed Ada Furst they knew to be some kind of schoolteacher—(these were boys born in Red Rock of parents from the Dominican Republic who lived upstairs from Ada)—and for a weak moment Ada considered asking them to accompany her … But no, these rude boys would only laugh at her. Or something worse.

Outside, Ada walked to the rear of the building. No one ever went here, or rarely: behind the tenement was a no-man’s-land of rubble-littered weeds and stunted trees, sloping to a ten-foot wire fence at the riverbank, against which years of litter had been blown and flattened so that it resembled now some sort of plaster art installation. In this lot tenants had dumped trash that included refrigerators, mattresses, chairs and sofas and even badly broken and discolored toilets. (Ada recognized a broken lamp that had once belonged to Kahola, her sister must’ve tossed out here. For shame!)

Ma and Karliss were right: Ada shouldn’t be here. Hadn’t there been a murder in this block, only a week ago, one in a series of young black boys shot multiple times in the back of the head, dragged into an abandoned house to bleed out and die …

But this person, if it was a person, was alive. Needing help.

Noise from jetliners in their maddening ascent from Newark Airport a few miles away, that began in the early morning and continued for hours even on weekends. Ada couldn’t hear the crying sound, with those damn jets!

Ada checked to see: was anyone following her? (The tall black-skinned Dominican boys, who hadn’t said a word to her though she’d smiled at them?) She made her way through the debris-strewn lot to the fence, that overlooked the river. Here she felt overwhelmed by the white, vertically falling autumn sunshine, that blinded her eyes. And the wide Passaic River with its lead-colored swift-running current that looked to her like strange sinewy transparent flesh, a living creature with a hide that rippled and shivered in the sunshine. Oil slicks, shimmering rainbows. The Passaic had once been a beautiful river—Ada knew, from schoolbooks—but since the mid-1800s it had been defiled by factories and mills dumping waste, all sorts of debris, tannery by-products, oil, dioxin, PCBs, mercury, DDT, pesticides, heavy metals. Upriver at Passaic was Occidental Chemical, manufacturers of the most virulent man-made poison with the quaint name—Agent Orange. Supposedly now in the late 1980s in these more enlightened times manufacturers had been made to comply with federal and state environmental laws; cleanups of the river had begun but slowly, at massive cost.

When she did move away from East Ventor, Ada thought, she would miss the river! That was all that she would miss, even if it was a poisoned river.

It had long been forbidden to swim in the Passaic—(still, boys did, including Ada’s twelve-year-old nephew Brandon: you saw them on humid summer days swimming off rotting docks)—and most of the fish were dead (if any survived you’d be crazy to eat them but every day, every morning at this time in fact, there were people fishing in the Passaic, mostly older black men with a few women scattered among them).

Ada’s grandfather Franklin had been one of the fishermen down by the docks, in the last years of his life. He’d been happy then, Ada had wanted to think. Bringing back shiny little black bass for her grandmother to clean, gut, sprinkle with bread crumbs and fry in lard. How much poison they’d all eaten, those years, not knowing any better or indifferent to knowing, Ada didn’t want to speculate.

This morning the river was bright and choppy. There were a few boats, at a distance. On the farther shore were shut-down factories and mills that hadn’t been operating since she’d been in high school. Vaguely she could remember her father and grandfather working at Pascayne Welding & Machine when she’d been a little girl in the 1960s, then later her father worked at Rand Alkali Pesticides until his health deteriorated and he’d been laid off. (The pesticide factory sprawling among seven acres of “hazardous” land within the Pascayne city limits had been shut down by the New Jersey Board of Health in 1977 for its toxic fumes and carcinogenic materials. There’d been a settlement between Rand Alkali and the State of New Jersey but whatever fines had been paid had made little difference to the sick employees like Ada’s father whose disability pension was less than his Social Security, and the two checks together came to less than he required to live with any dignity in even the shabby tenement at 1192 East Ventor.)

Ada listened: there came the crying again. Now, it sounded like a plaintive mewing, that had all but given up hope.

Definitely, the sound was coming from the old Jersey Foods factory next-door.

The fish-canning factory was a ruin that would one day slide into the river, next time it flooded. Last time, the spring of 1985, filthy river-water had risen into the factories on the riverbanks as into the dank dirty cellars of residences like Ada’s. A powerful stink had prevailed for weeks. The state had declared a disaster area for some and a makeshift shelter had been established in the high school gymnasium and the Pascayne Armory. Fortunately, Ada and her family hadn’t had to be evacuated. Kahola had been living with them then.

Approaching the factory with its broken, boarded-over windows Ada tried not to think This is a mistake. I am making a mistake.

There was no man in her life, as there’d been in her sister’s life. Not a single man in Kahola’s life but numerous men. Ada was too free to make decisions of her own, too reckless. It was the price of her female independence and a certain stiffness, resentment even, about inhabiting a fleshy female body. Oh, she was frightened now. But damn if she’d turn back. She cupped her hands to her mouth and called: “Hello? Is anybody there?”

The cries seemed to be coming from the factory cellar. Bad enough to be inside the nasty fish-factory, but—in the cellar! There were steps leading down, a door that had been forced open years ago. Everywhere was filth, storm debris and mud. Ada drew a deep breath and held it.

She thought—It’s only a cat. A trapped starving cat.

A wounded cat.

Planning how she would trap the cat—in a box?—somehow—and take it to an animal shelter.

(But how practical was that? The shelter would euthanize the cat. Better to keep the cat.)

(But she couldn’t keep the cat! No room for a scrawny diseased alley cat in their place already too small and cramped for the people who lived there.)

It was 8:20 A.M. It was a bright cool Sunday morning in October. Ada Furst would recall how she made her way into the cellar down a flight of steps littered with broken glass and pieces of concrete as she continued to call in a quavering voice—“Hello? Hello?” A pale, porous light penetrated the gloom, barely.

The cry came louder. Desperate.

Ada blinked into the shadows. Ada took cautious steps. She could hear someone whispering Help me help me help me.

Then she saw: the girl.

The girl was lying on the filthy floor in the cellar not far from the entrance, on her side facing Ada, on a strip of tarpaulin, as if she’d been dragged partway beneath a machine. She appeared to be tied, wrists and ankles, behind her back. It looked as if there’d been a wadded rag in her mouth, she’d managed to spit out. And around the girl’s head was a cloth or a rag she’d worked partway off. Her hair was matted with mud and something very smelly—feces? Ada began to gag. Ada began to scream.

“Oh God. Oh God! My God.”

A girl of thirteen, or fourteen. On the filthy floor, she looked like a child.

Ada was stricken with horror believing that the girl was dying: she would be a witness to the girl’s death. She’d wasted so much time—she’d come too late—the girl was shivering uncontrollably, as if convulsing. Ada crouched over her, hardly daring to touch her. Where were her injuries? Was she having a seizure? Ada had a confused sense of blood—a good deal of blood—on the tarpaulin, and on the floor. It seemed to her that the girl had been mutilated somehow. The girl’s bones had been broken, her spine deformed. Ada would swear to this. She would swear she’d seen this. Certainly the girl’s face was swollen, her eyes blackened and bruised. Dark blood had coagulated at her nose, that looked as if it had been broken. How young the girl seemed, hardly more than a child! Her clothing was torn and bloody. Her small breasts were bared, covered in a sort of filthy scribbling. Cruelly her legs were drawn up behind her back, hog-tied.

Ada was telling the girl she was here, now. She would take care of her, now. The girl would be all right.

“Is it—Sybilla? Sybilla Frye?”

Feebly the girl tried to free herself, moaning. Ada pulled at the ropes binding her wrists and her ankles, which were thin ropes, like clothesline—tugged at them until a knot came loose and she could lift the girl in her arms, into a partially sitting position on the filthy tarpaulin. The stench of dog shit was overwhelming. The girl was shivering in terror. Saying what sounded like They say they gon come back an kill me—don let em kill me! When Ada tried to lift her farther, out of the filth on the tarpulin, the girl began to squirm and fight her, panting. She seemed not to know who Ada was. Her eyes rolled back in her head. She fell back heavily, as if lifeless. Ada would not wonder at how readily the knotted rope had come loose, at this time. Ada was begging the girl: “Don’t die! Oh—don’t die!”

Yes I saw she was Sybilla Frye. I saw that right away.

Ada Furst ran stumbling and screaming for help.

A first-floor resident in her building called 911.

An ambulance from St. Anne’s Hospital, two miles away on the other side of the river, arrived in sixteen minutes.

The first query on the street would be—She goin to live?

Then—Who done this to that girl?

“White Cop” (#ulink_22b63886-ba0e-5299-a07b-75dad7e5fb19)

OCTOBER 7, 1987

Jesus help me

Say they gon kill me, I tell anybody Dear Jesus help me, they hurt me so bad and they will do worse they say next time my mama they gon hurt bad an my lit sister an any nigra they find where I live, they told me they will murder us all

They was hopin I would die, they leave me in this place to die sayin you be eaten by beetles nasty black cunt you deserve to die you are SO UGLY

Thought I heard say there was other dead nigras in this place they was laughin about where they drag me thinkin I would not live this like cellar-place they say, you will die here an beetles eat you only just bones left nobody gon recognize by the time those beetles finish with you

They had white faces an one of them a badge like a cop would wear or a state trooper an they had guns an one of them, he put that gun barrel up inside me and it hurt so bad I was crying so bad they said Nigra cunt you stop that bawlin, we gon pull this trigger an all yo’ insides gon come splashin out your ugly nappy head

And they laugh, laugh some more

All the time they be laughin like they are high on somethin smokin crack, I could smell

The Pis’cyne cops they con-fis-cu-ate the crack an smoke it for themselves, why they are crazy to kill black people they white bosses tell them, you give us our percent of the money we be OK how you behave

Grabbed me from behind where I was walkin from school in the alley behind the car wash on Camden some kind of canvas they pulled down over my head like a hood and I was screamin but couldn’t get free to breathe Thought I would die an was cryin Mama! Mama! till they stuffed a rag in my mouth near to choking me O Jesus

It was in the back of a van it was a police van, I think there was a siren they were laughin to use a cop can use a siren any time he wishes they drove to underneath the bridge I could hear the echo up under the bridge I could recognize that sound like when we were little and played there, and put our hands to our mouths and called up under the bridge and it was like pigeons cooing and the echo coming back and the water lapping except now, I could not hear any echo the white men were laughin at me took turns kicking and beating and strangling me raped me like with they guns and fingers sayin they would not put their pricks in a dirty nasty disease nigra cunt they jerked themselves off onto my face that’s what they done they said, swallow that, you ignorant nigra bitch how many times how many of them they was who hurt me, I could not see I thought five, maybe five—their faces were white faces—there was a badge this one was wearin, shiny spit-in-your-face badge like a cop wear or a state trooper an they laughin at me sayin nobody will believe a dirty nigra cunt taking her word against the word of decent white men

The van, they drove somewhere else then here was maybe other men came into it it was a night and a day and a night I was hurt so bad, my eyes was puffed shut I was fainted from the bad hurt and bleedin up inside me it was all sore and bleedin and my mouth, and my throat they’d stuck the gun barrel down into my throat too there was more than one of them did it they said, this is what you like black nigra cunt aint it

Tied me so tight like you’d tie a hog no water and no food, they was hopin I would weaken and die some of them went away, an other ones came in their place Nigra hoar of babyland they was laughin

I could not see their faces mostly I heard their voices

There was one of them, a young one he was sayin why dint they let him blow out the nigra cunt’s brains he would do it, he said

In my hair and on my body they smeared dog shit to shame me when they was don with me two of them dragged me from the van to that place in the cellar they put they foot on the back of my head to press into the earth they would leave me there, they said beetles would eat me and nobody give a damn about some ugly nappy lit nigra girl if she live or die and nobody believe her, that a joke to think!

O Jesus help me I am afraid to die, Jesus help me I have been a bad girl is this how I am punished, Jesus an Jesus say, the last shall be first an the first shall be last an a litl child shall lead them AMEN

St. Anne’s Emergency (#ulink_b6c35b9e-0bfb-521c-9938-91f99d85434f)

OCTOBER 7, 1987

She’d been left to die.

She’d been beaten, and raped, and left to die.

She’d been hog-tied, beaten and raped and left to die.

Just a girl, a young black girl. Dragged into the cellar of the old fish-factory and if she hadn’t worked the gag out of her mouth, to call for help, she’d have died there in all that filth.

It was that 911 call. That call you’d been waiting for.

You’d expect it to be late Saturday night. Or Friday night. Could be Thursday night. You would not expect the call to be Sunday morning.

And that neighborhood by the river, East Ventor and Depp. Those blocks east of Camden Avenue. High-crime area the newspapers call it. After the fires and looting of August 1967 spilling over from the massive riot in Newark, the neighborhood hadn’t ever recovered, Camden Avenue west for five or six miles looking like a war zone twenty years later, shuttered storefronts, dilapidated and abandoned houses, burnt-out shells of houses, littered vacant lots and crudely hand-lettered signs for rent for sale that looked as if they’d been there for years.

Many times, the calls come too late. The gunfire-victim is dead, bled out in the street. The baby has suffocated, or has been burnt to death in a spillage of boiling water off a stove. Or the baby’s brains have been shaken past repair. Or there’s been a “gas accident.” Or a child has discovered a (loaded) firearm wanting to play with his younger sister. Or a man has returned to his home at the wrong time. Or a drug deal has gone wrong. (This is frequent.) Or a drug dose has gone wrong. (This is frequent.) Or a space heater has caught fire. Or a carelessly flung burning cigarette has caught fire. Or a woman has swallowed Drano and has lain down to die. Or a gang of boys has exchanged multiple shots with another gang of boys. Or a pit bull maddened by hunger has attacked, sunk its fangs into an ankle and will not release the crushed bones until shots from a police service revolver are fired into its brain.

Calls of desperation, dread. But exhilaration in being so summoned, in a speeding ambulance, siren piercing the air like a glittering scimitar.

You are propelled by this speed. You are addicted to the thrill of danger, this not-knowing into which you plunge like a swimmer diving into a swirling river to “rescue” whoever he can.

But now there is this call—to change your life in a way you will regret.

Damn it wasn’t true the ambulance had taken its time getting there! Sixteen minutes but we’d been slowed down on the bridge and the 911 dispatcher had given us an incomplete address.

It being a black neighborhood, it would be claimed. The EMTs from St. Anne’s had taken their time.

We’d responded to the dispatcher as we always did.

We said, there was no difference between this emergency summons and any other—except what would be made of it, later.

When we arrived at the corner of East Ventor and Depp we hadn’t known immediately where to go. The dispatcher hadn’t been told clearly where the injured girl was.

Something about a factory. Factory cellar.

So we’d wasted minutes determining what this meant. We’d been told “cellar”—so we had flashlights in case flashlights were needed. Searching for a way through the chain-link fence until a woman appeared and screamed at us about a “dying girl”—a girl “bleeding to death”—and directed us where she was.

First thing we observed was that the girl (later identified as “Sybilla Frye”) lying on her side on the cellar floor on a strip of tarpaulin seemed to be conscious but would not respond to us, as if she was unconscious.

When we came running down into the cellar with flashlights we saw that the girl’s eyes were open but immediately then she shut them when the light came onto her face. We saw her lift her hands to hide her face from the bright light.

It was our concern that the girl was in severe physical distress, in shock, or bleeding internally, we had to determine immediately, or try to determine, before lifting her onto a stretcher.

Her face was bloodied and battered. There was a towel or a rag partly tied around her head and her hair was matted with filth.

There were no evident deep lacerations of the kind made with a sharp weapon or gunshot. Wounds were superficial, though bloody. There did not appear to be a severe or life-threatening loss of blood.

There was a strong smell of excrement—possibly human, or animal.

It looked like the girl had been tied with a clothesline but when we arrived, the clothesline had been untied. The woman who’d met us outside said she’d found the girl tied and had untied the girl. Her wrists and ankles had been tied behind her—“hog-tied.”

Well, we thought there was something strange—the injured girl had been communicating with the woman who’d found her, the woman told us—but then, she wouldn’t communicate with us.

She was limp and her arms were, like, falling loose—like a person would be if she was unconscious. But when we touched her she stiffened up. She’d shut her eyes tight and kept them shut.

That girl was in a state of shock! She didn’t know who we were.

We identified ourselves. She had to know we were a rescue team.

But she was scared! She was terrified. She was just a girl and somebody had almost killed her. She might’ve thought we were her assailants coming back. She was shivering—her skin felt clammy when I touched her.

She never did talk to us. Not a word.

It was possible, I thought, she was—you know—mentally disabled like retarded, or autistic. She communicated with me …

She did not communicate with you. She was not observed communicating with you.

She didn’t talk to me exactly but, but she—communicated …

Look—this was not a “cooperative” individual. First thing when we came down into the cellar with flashlights we saw the girl’s eyes were open and she’s staring at us—then, she shut her eyes. We saw her lifting her hands to hide her face from the bright light—which you wouldn’t do if you were unconscious.

The lights blinded her and scared her …

Had a damn hard time taking her blood pressure and pulse and trying to check for injuries, she kept bending her legs and wouldn’t lay them flat so we could strap her down.

Sometimes it happens, an injured person is panicked and doesn’t want to be taken to the ER.

But this girl refused to talk to us. She wasn’t screaming or saying she didn’t want medical treatment. She wasn’t hysterical or crazy. She was trying to simulate being unconscious but she was awake and alert. You could see her eyeballs kind of jerking around behind her eyelids. You could see she’d been assaulted, a strong possibility she’d been raped, her clothes were torn partly off except she was still wearing jeans—bloodied jeans.

The visible injuries were lacerations and bruises on her face, her chest, her belly—where her clothes had been ripped, you could see.

The woman had been screaming the girl was “bleeding to death” but that was not the case.

Most of the blood appeared to be dried, coagulated. Whenever she’d been beaten, it hadn’t been recently.

She’d been beaten and left to die! Tied and a gag in her mouth and left to die in that nasty place! When we found her, she was in a state of shock.

Actually she was not in a “state of shock”—her blood pressure wasn’t low, we discovered when we were finally able to take it, and her pulse was fast.

She was in, like, emotional shock …

The woman was explaining she’d been wakened by “some kind of crying” in the night then in the morning she’d searched outside and found the girl tied and bleeding and left to die and she was worried since she’d moved the girl a little, started to lift her off the tarpaulin, maybe the girl had a skull fracture or broken spine or internal injuries she might’ve made worse, she wanted to tell us that.

The woman was kind of hysterical herself. She looked like her heart was jumping all over inside her chest. Said she was a schoolteacher and the girl had been one of her pupils …

Kept saying she’d thought the girl had been thrown down from some height, and her back was broken. She’d thought the girl was bleeding to death, that’s what she’d told us when we first arrived. And the girl had been raped, she was sure of that …

She’d wanted to come in the ambulance with us but we had to tell her no. We told her to notify the girl’s mother.

That poor girl was in a state like panic. Maybe it wasn’t “shock” but she was panting—hyperventilating. Her skin was clammy like death.

Well—anybody would be scared and upset, in her circumstances. With just the flashlights we could see it had been a vicious attack. And you’d think for sure, rape. The disgusting thing was what was smeared in her hair and on the parts of her body that had been naked—mud and dog shit. And in the ambulance we saw something spelled out on her body.

These nasty words! Smeared in dog shit on that poor girl.

It wasn’t dog shit the words were written in, it was some kind of smeared ink like a marker pen.

It was dog shit, too. I saw it.

The scrawled words were in black marker pen. It was hard to make out what they were because the ink was smeared, and the girl’s skin was kind of dark …

The thing is, if you are unconscious, your limbs are not stiff and you don’t resist medical intervention. If you are conscious, you might resist—if you are terrified and panicked. But we got a blood pressure reading finally and she wasn’t in shock—or anywhere near—her pressure was 130 over 115. Her pulse was fast but not racing.

You could see that somebody had hurt her bad! There’d been more than one of them, they’d kicked her and cut her and left her to die in that nasty place.

In the ER in the bright lights you could see these words scrawled on her chest and belly you couldn’t read too well because the letters were smeared and distorted NIGRA BITCH KU KUX KLANN.

(Right away I had to wonder—why’d anybody write words on somebody’s body upside-down?)

NIGRA BITCH—this was just below the girl’s breasts, on her midriff.

KU KUX KLANN—this was on the girl’s belly just above her navel.

Photos were taken of these racist words as photos were taken of the girl’s injuries. This is ER procedure in such cases. When the flashes went off Sybilla Frye tried to hide her face making a wailing sound like Noooo.

It was our assumption she’d been raped—very possibly, gang-raped. Her clothes were ripped and bloody and her lower belly and thighs were bruised, we saw when we got the jeans pulled down. (She fought us pretty desperately about that—pulling down her jeans.) Her face had sustained the worst injuries. Both her eyes were blackened and her upper lip was swollen to twice its size, like a goiter.

A brutal gang-rape is not a common incident even in inner-city Pascayne. Yet, a brutal gang-rape is not an uncommon incident in inner-city Pascayne.

When she was first brought in Sybilla Frye hadn’t been ID’d yet. We didn’t know her name or address or who to contact. The EMTs couldn’t help us much. We were asking her questions but she kept pretending to be unconscious and unable to hear us when it was obvious that she was conscious and she was hearing us.

I was the ER physician on duty, Sunday morning October 7.

Right away I said to her, “Miss? Open your eyes, please.” Because I had to examine her eyes. I had to determine if possibly she’d had a concussion or a skull fracture. I’d be ordering X-rays including X-rays of her skull. But still she wouldn’t open her eyes. She was so tense, you could feel her body quivering. Yet she refused to cooperate. She pretended to be unconscious the way a small child might pretend to be “asleep.” It isn’t easy to pretend you’re unconscious when you’re conscious. You might think it is, but it isn’t. I lifted one of her arms over her head and released it and immediately she deflected her arm to avoid striking her face—it’s a reflex you can’t help. Clearly, this girl who’d be identified as “Sybilla Frye” was conscious in the ER and in control of her reactions. I could see she’d been injured—that was legitimate—I felt sorry for her but this kind of uncooperative behavior would impede us in our treatment so I said, “Miss, you can hear me. So open your eyes”—and finally she did.

Looked at Dr. D___, like she was terrified of him.

Dr. D___ is Asian, light-skin. Later it came out she was afraid of him, he’d looked “white” to her.

Of the EMTs, just one of us was “white”—“white Hispanic.” The others were dark-Hispanic, African-American. Yet, she’d acted scared of us.

She was terrified! Just so scared …

She wasn’t hysterical but she was—she wasn’t—you had to concur she wasn’t in her right mind and under these circumstances you couldn’t blame her for not cooperating. She didn’t seem to understand where she was, or what was happening …

She understood exactly where she was, and exactly what was happening. She didn’t wish to cooperate, that’s all.

I did wonder why she wasn’t crying—most girls would’ve been crying by now. Most women.

We treated her for face wounds. Lacerations, black eyes, mashed nose, bloody lip. A couple of loosened teeth where he’d punched her. (You could almost see the imprint of a man’s fist in her jaw. But he hadn’t strangled her, there were no red marks around her throat.) The blood wasn’t fresh but had coagulated in her nostrils, in her hair, etc. By their discolorations you could see that the bruises were at least twenty-four hours old. Also the blackened eyes. We gave her stitches for the deepest cuts in her eyebrow and on her upper lip. She reacted to the stitches and disinfectant so we had to hold her down but she still didn’t say any actual words only just Noooo. We wondered if she was, like, a Dominican who didn’t know English, or—there’s Nigerians in Pascayne—maybe she was Nigerian …

There were Hispanic nurses we called in, to try to talk to her in Spanish—she ignored them completely.

Where (presumably) the rope had been tied around her wrists and ankles there were only faint red abrasions on the skin. No deep abrasions, welts, or cuts.

We couldn’t get a blood sample. That wasn’t going to happen just yet.

Pascayne police officers were just arriving at the factory when the EMTs bore the girl away in the ambulance. The bloodied tarpaulin and other items were left there for the police to examine and take away as evidence.

Soon then, police officers began to arrive at St. Anne’s ER.

The hard part was—the pelvic exam …

We had to determine if she’d been raped. Had to take semen samples if we could. Any kind of evidence like pubic hairs, we had to gather for a rape kit, but the girl was becoming hysterical, not pretending but genuinely hysterical kicking and screaming No no don’t hurt me NO! Dr. D___ was angry that the girl seemed determined to prevent a thorough examination though such an examination was in her own best interests of course. We were able to examine her and treat her superficially and it took quite a while to accomplish that with her kicking, screaming, and hyperventilating and the orderlies having to hold her down …

(Now we knew, at least—she could speak English.)

She continued to refuse to allow Dr. D___ to examine her just clamped her legs together tight and screaming so Dr. D___—(flush-faced, upset)—asked one of the female interns to examine her; this young woman, Dr. T___, was a light-skinned Indian-American who was able to calm the girl to a degree and examined her pelvic area by placing a paper cover over the girl’s lower body but when Dr. T___ tried to insert a speculum into the girl’s vagina the girl went crazy again kicking and screaming like she was being murdered.

Like she was being raped …

It was a terrible thing to witness. Those of us who were there, some of us were very upset with Dr. D___’s handling of the situation.

By this time, the mother had arrived. The mother had been notified and someone had driven her to the hospital and before security could stop her she’d run into the ER hearing her daughter’s screams and began screaming herself and behind her, several other female relatives, or neighbors—all these women screaming and our security officers overwhelmed trying to control the scene …

Pascayne police arrived at the ER. Trying to ask questions and the girl refused to acknowledge anyone shutting her eyes tight and screaming she wanted to go home and the mother was saying My baby! My baby! What did they do to my baby!

You couldn’t get near the girl without her screaming, kicking and clawing. We’d have sedated her but the mother was threatening to sue us if we didn’t release her daughter.

(It is strange that a mother would want her daughter released into her custody out of the ER, before she knew the extent of her daughter’s injuries. It is strange that the mother, like the daughter, refused X-rays, a blood test, but it is not so very uncommon under these circumstances. We are accustomed to delusional behavior and violence in the ER. We are accustomed to patients dying in the ER and their relatives going berserk. Yet, this seemed like a special case.)

We were trying to explain: the girl had to have X-rays before being discharged.

It was crucial, the girl had to have X-rays.

If she’d suffered a concussion, or had a hairline fracture in her skull, or had broken or sprained bones—it was crucial to determine this before she left the hospital.

If there was bleeding in her brain, for instance.

And we needed to do blood work. We needed to draw blood.

Mrs. Frye didn’t give a damn for any of this. In a furious voice saying how her daughter had been missing three days and three nights and wherever she’d been there were people who knew more than they were revealing and she’d come to take her daughter home, now.

They took my baby from me, now I’m bringin my baby home can’t none of you stop me.

The Pascayne police officers set her off worse. When an officer from Child Protective Services tried to speak with Mrs. Frye she backed off stretching her arms out as if to keep the man from assaulting her. She was saying You aint gon arrest me, you aint gon put cuffs on me, you leave me alone seein what you done to my baby aint that enough for you.

Mrs. Frye’s fear of the police officers appeared to be genuine.

By this time Sybilla Frye was sitting up on the gurney with her knees raised against her chest trying to hide herself with the crinkly white paper and making a noise like Nnn-nnn-nnn—like she was so frightened, she was shivering convulsively. You could hear her teeth chatter. And now she was crying, like a child Mama don let them take me, Mama take me home …

The mud and dog-feces had been removed from the girl’s hair.

We’d had to cut and clip some of her hair in order to get this matter out. It would be charged afterward that we had defiled and disfigured Sybilla Frye—we had deliberately cut her hair in a careless and jagged fashion.

Her body covered in filth had been washed but the racist slurs in black Magic Marker ink remained on her torso and abdomen, more or less indecipherable.

(It would be recorded in the ER photos that these words had been written upside-down on Sybilla Frye’s body.)

(Well, you’d think—as if Sybilla Frye had written the words herself, right? But a clever assailant might’ve written the words on her body standing behind her so that she could read the words. Or—he’d written the words upside-down purposefully so the victim would be accused of lying. That was possible.)

(Seeing the racist words on the girl’s body we’d had to notify the FBI right then. This is protocol if there is a probable “hate crime” as there certainly was in this case.)

In an emergency unit in a city like Pascayne, New Jersey, you are half the time reporting crimes and taking such photos for forensic use. If your patient dies, you may be the only witnesses.

The FBI had to be notified immediately which the ER administrator did without either the injured girl or her mother knowing at the time.

Mrs. Frye was demanding to speak with her daughter “in private” if we wouldn’t release the girl so she could take her home. Dr. D___ allowed this.

Mrs. Frye jerked the curtain shut around the cubicle.

For some minutes, Mrs. Frye and Sybilla whispered together.

Police officers were asking the ER staff and the EMTs what had happened and we told them what we knew: Mrs. Frye had ID’d her daughter who was “Sybilla Frye”—“fourteen years old”—(in fact, it would be revealed later that Sybilla Frye was actually fifteen: she’d been born in September 1972); the girl had been assaulted and had sustained a number of injuries; she’d been struck by fists and kicked, but she didn’t seem to have been attacked with any weapons; cuts in her face had been made with a fist or fists, not a sharp instrument; there were no gunshot wounds; her face, torso, belly, legs and thighs were bruised, and there appeared to be evidence of bruising in the vaginal area, but without a pelvic exam it wasn’t possible to determine if there had been sexual penetration or any deposit of semen.

Skin samples taken from the girl’s body would be tested for DNA and these might contain semen. Other tests would be run, to determine if a sexual offense had been committed.

Mrs. Frye had claimed that her daughter had been “kidnapped” and “locked up” somewhere for three days and three nights. During this time, Mrs. Frye had been looking for the girl “everywhere she knew” but no one had seen her. Then, that morning, Sybilla Frye had been discovered by a woman who lived near the Jersey Foods factory, who’d heard the girl “crying and moaning” in the night.

So far, Sybilla Frye had not identified nor even described her assailant or assailants. She had not communicated with the ER staff at all.

She had not allowed a pelvic exam, nor had she consented to a blood test.

Despite the mother’s claim that she’d been kept captive somewhere for three days, Sybilla Frye did not appear malnourished or dehydrated.

This is some of what we told Pascayne police.

After approximately ten minutes of whispered consultation, Mrs. Frye drew back the curtain. She was deeply moved; her face was bright with tears. She’d been wiping her daughter’s face with tissues and now she was demanding that she be allowed to take her daughter home, it was a “free country” and unless they was arrested she was taking S’billa home.

(Ednetta Frye would afterward claim that she’d had to clean her daughter of mud and dog shit herself, the ER staff had not “touched a cloth” to Sybilla. She would claim that she’d carried her baby in her arms out of the ER, filth still in the girl’s hair and on her body, and her body naked, covered in only a “nasty” blanket as the ER staff had cut off her clothes for “evidence.”)

An officer from Juvenile Aid had arrived. But Mrs. Frye refused to allow Sybilla to speak to this woman, as she’d refused to allow Sybilla to speak to the officer from Child Protective Services.

It was explained to Mrs. Frye that since a crime or crimes had been committed, Sybilla would have to be interviewed by police officers—she would have to give a “statement”—when she was well enough … Mrs. Frye said indignantly That girl aint gon be “well enough” for a long time so you just let her alone right now. I’m warnin you—let my baby an me alone, we gon home right now or I’m gon sue this hospital an every one of you for kidnap and false imprisonment.

But finally Mrs. Frye relented, saying she would allow Sybilla to talk to a cop—One of her own kind, and a woman—if you have one in that Pas’cyne PD.

The Interview (#ulink_af16bda9-ec12-5061-a2aa-14f51678f892)

It was not an ideal interview. It did not last beyond twenty stammered minutes.

It would be the most frustrating interview of her career as a police officer.

She’d been bluntly told that a black girl beaten and (possibly) gang-raped had requested a black woman police officer to interview her at the St. Anne’s ER.

Getting the summons at her desk in the precinct station late Sunday morning she’d said, D’you think I’m black enough, sir?—in such a droll-rueful way her commanding officer couldn’t take offense.

She couldn’t take offense, she understood the circumstances.

She was not minority hiring. She didn’t think so.

She’d been on the Pascayne police force for eleven years. She had a degree from Passaic State College and extra credits in criminology and statistics as well as her police training at the New Jersey Academy. She was thirty-six years old, recently promoted to detective in the Pascayne PD.

As a newly promoted detective she worked with an older detective on most cases. This would be an exception.

Iglesias did not check black when filling out appropriate official forms. Iglesias did not think of herself as a person of color though she acknowledged, seeing herself in reflective surfaces beside those colleagues of hers who were white, that she might’ve been, to the superficial eye, a light-skinned Hispanic.

Her (Puerto Rican–American) mother wasn’t her biological mother. Her (African-American) father wasn’t her biological father. Where they’d adopted her, a Catholic agency in Newark, there was a preponderance of African-American babies, many “crack” and “HIV” babies, and Iglesias did not associate herself with these, either. Her (adoptive) grandparents were a mix of skin-colors, a mix of racial identities—Puerto Rican, Creole, Hispanic, Asian, African-American and “Caucasian.” There was invariably a claim of Native-American blood—a distant strain of Lenape Indians, on Iglesias’s father’s side. The Iglesias family owned property in the northeast sector of Pascayne adjacent to the old, predominantly white sector called Forest Park; they owned rental properties and several small stores as well as their own homes. It was not uncommon for a young person in Iglesias’s family to go to college—Rutgers-Newark, Rutgers–New Brunswick, Bloomfield College, Passaic State. The most talented so far had had a full-tuition scholarship from Princeton. They did not think of themselves and were not generally thought of as black.

Iglesias did not take offense, being so summoned to St. Anne’s ER. Something in her blood was stirred, like flapping flags in some high-pitched place, by the possibility of being in a position unique to her.

For racism is an evil except when it benefits us.

She liked to think of being a police officer as an opportunity for service. If not doing actual good, preventing worse from happening. If being a light-skinned female Hispanic helped in that effort, Ines Iglesias could not take offense and would not take offense except at the very periphery of her swiftly-calculating brain where dwelt the darting and swooping bats of old hurts, old resentments, old violations and old insults inflicted upon her haphazardly and for the most part unconsciously by white men, black men, brown-skinned men—men.

With excitement and apprehension Sergeant Iglesias drove to St. Anne’s Hospital. The emergency entrance was at the side of the five-story building.

This was not a setting unfamiliar to Ines Iglesias. She had witnessed deaths in this place and not always the deaths of strangers.

Just inside the ER, a patrol officer led her into the interior of the unit where the (black) girl believed to have been gang-raped was waiting, inside a curtained cubicle.

In the ER she noted eyes moving upon her—fellow cops, medics—in wonderment that this was the officer sent to the scene as black.

Cautiously Iglesias drew back the curtain surrounding the gurney where the stricken girl awaited. And there, in addition to the girl, was the girl’s mother Ednetta Frye.

Sybilla Frye was a minor. Her mother Ednetta Frye had the right to be present and to participate in any interview with Sybilla conducted by any Pascayne police officer or social worker.

Too bad! Iglesias knew this would be difficult.

Iglesias introduced herself to Sybilla Frye who’d neither glanced at her nor given any sign of her presence. She introduced herself to Ednetta Frye who stared at her for a long moment as if Mrs. Frye could not determine whether to be further insulted or placated.

Iglesias addressed Mrs. Frye saying she’d like to speak to Sybilla for just a few minutes. “She’s had a bad shock and she’s in pain so I won’t keep her long. But this is crucial.”

Iglesias had a way with recalcitrant individuals. She’d been brought up needing to charm certain strong-willed members of her own family—female, male—and knew that a level look, an air of sisterly complicity, shared indignation and vehemence were required here. She would want Mrs. Frye to think of her as a mother like herself, and not as a police officer.

Extending her hand to shake Ednetta Frye’s hand she felt the suspicious woman grip her fingers like a lifeline.

“You ask her anythin, ma’am, she gon tell you the truth. I spoke with her and she ready to speak to you.”

Mrs. Frye spoke eagerly. Her breath was quickened and hoarse.

Not a healthy woman, Iglesias guessed. She knew many women like Ednetta Frye—overweight, probably diabetic. Varicose veins in her legs and a once-beautiful body gone flaccid like something melting.

Yet, you could see that Mrs. Frye had been an attractive woman not long ago. Her deep-set and heavy-lidded eyes would have been startlingly beautiful if not bloodshot. Her manner was distraught as if like her daughter she’d been held captive in some terrible place and had only just been released.

But when Iglesias tried to speak to Sybilla Frye, Mrs. Frye could not resist urging, “You tell her what you told me, S’b’lla! Just speak the words right out.”

The battered girl sat slumped on the gurney wrapped in a blanket, shivering. Iglesias found another blanket, folded on a shelf, and brought it to her, and drew it around her thin shoulders. Close up, the girl smelled of disinfectant but also of something foul and nauseating—excrement. Her hair was oily and matted and had been cut in a jagged fashion as if blindly.

With both adult women focused upon her, Sybilla seemed to be shrinking. Her shut-in expression was a curious mixture of fear, unease, apprehension, and defiance. She seemed more acutely aware of her mother than of the plainclothes police officer who was a stranger to her.

Between the daughter and the mother was a force field of tension like the atmosphere before an electric storm which Iglesias knew she must not enter.

Iglesias asked the girl if she was comfortable?—if she felt strong enough to answer a few questions?—then, maybe, if the ER physician OK’d it, she could go home.

A trauma victim resembles a wounded animal. Trying to help, you can exacerbate the hurt. You can be attacked.

“Sybilla? Do you hear me? My name is Ines—Ines Iglesias. I’m here to speak with you.”

Gently Iglesias touched Sybilla’s hand, and it was as if a snake had touched the girl—Sybilla jerked back her hand with an intake of breath—Ohhh!

There was something childish and annoying in this behavior, Iglesias thought. But Iglesias wanted to think The girl has been badly hurt.

Mrs. Frye said sharply to her daughter, “I’m tellin you, girl. You just answer this p’lice off’cer’s questions, then we goin home.”

Sybilla continued to hunch shivering inside the blanket. She had shut her eyes tight as a stubborn child might do. Her upper lip, swollen like a grotesque discolored fruit, was trembling.

Iglesias had been told that the girl’s assailants had rubbed mud and dog excrement into her hair and onto her body and that they’d written racist words in black ink on her body.

When she asked if she might see these words, Sybilla stiffened and did not reply.

“If you could just open the blanket, for a minute. The curtain is closed here. No one will see. I know this is very unpleasant, but …”

Sybilla began shaking her head vehemently no.

In a plaintive voice Mrs. Frye said, “She don’t need to do that no more, Officer. S’b’lla a shy girl. She don’t show her body like some girls. They took pictures of the writing, they can show you. That’s enough.”

“I would so appreciate it, if I could see this ‘writing’ myself.”

“Ma’am, that nasty writin is all but gone, now. I think they washed it off. But they took pictures. You go look at them pictures.”

“If I could just—”

“I’m tellin you no, ma’am. It’s enough of this for right now, S’billa comin home with me.”

Iglesias had been briefed about the “racist slurs”—scribbled onto the girl’s body “upside-down.” Clearly it was already an issue to arouse skepticism—upside-down? She would study the photos and see what sense this might make.

Iglesias had placed a recording device on the examination table. Mrs. Frye objected: “You recordin this, ma’am? I hope you aint recordin this, I can’t allow that.”

The small spinning wheels were a provocation. Iglesias had known that Mrs. Frye would object.

Carefully she explained that it was police department policy that such an interview would be recorded. “A recorded interview is for the good of everyone involved.”

“No it ain’t, ma’am! Like with pictures you can mess up what people say to twist it how you want. Like on TV. You can leave out some words an add some others the way police do, to make people ‘confess’ to somethin they ain’t done. You got to know that, you a cop you’self.”

Mrs. Frye spoke sneeringly. The sudden hostility was a surprise.