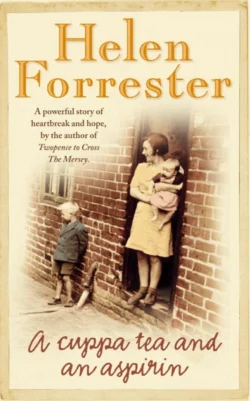

A Cuppa Tea and an Aspirin

Helen Forrester

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 861.19 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: A powerful new novel, heart-breaking but ultimately uplifting, from the author of the classic Twopence to Cross The Mersey.Life in a Liverpool tenement block during the Great Depression is a grim struggle for Martha Connelly and her poverty-stricken family, as every day renews the threat of homelessness, hunger and disease.Family warmth remains constant however, despite the misery and disquiet of the slum surroundings, and the indomitible neighbourhood puts up a relentless fight for survival.Helen Forrester’s poignant novel relays bleakness and hardships, but celebrates also the spirit of unified hope and the restorative values of the close-knit community.