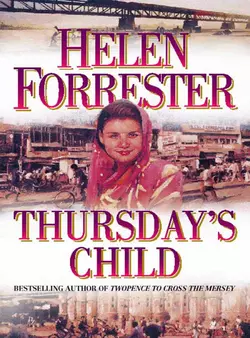

Thursday’s Child

Helen Forrester

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 544.32 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: Helen Forrester’s moving story of an English girl and her love affair with an Indian man.Peggy Delaney was a Lancashire girl born and bred, beginning to live again after the heartache of the war.Ajit Singh was a charming young Indian student, shortly to return to his homeland and an arranged marriage.When Peggy and Ajit fell in love, each one knew the future would not be easy. But as they began their new life, far from their homes and their families, they found that love could bring two worlds together…