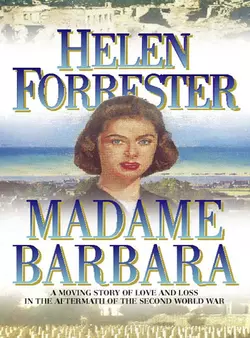

Madame Barbara

Helen Forrester

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 580.23 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: A wonderful new novel from Liverpool’s best-loved author. A tale of loss and love set in post-Second World War England and France.This is the story of a young Liverpool woman widowed in the Second World War before she can know the happiness of having a family. With the blessing of her mother, with whom she runs a B&B, she goes to Normandy to see where her husband was killed in the D-Day landings. Once she is there, she meets an impoverished French poultry farmer, now reduced to driving a beaten up (and still rare) taxi and looking after his old mother and dying brother. Will these two find happiness together?A touching love story, a compelling portrayal of the aftermath of war and above all a testament to the courage and endurance of oridinary people, Madame Barbara will delight Helen Forrester’s countless fans.