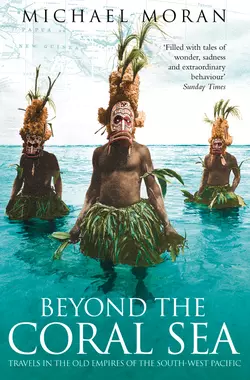

Beyond the Coral Sea: Travels in the Old Empires of the South-West Pacific

Michael Moran

A romantic and adventurous journey to the hidden islands and lagoons beyond Papua New Guinea and north of Australia.East of Java, west of Tahiti and north of the Cape York peninsula of Australia lie the unknown paradise islands of the Coral, Solomon and Bismarck Seas. They were perhaps the last inhabited place on earth to be explored by Europeans, and even today many remain largely unspoilt, despite the former presence of German, British and even Australian colonial rulers.Michael Moran, a veteran traveller, begins his journey on the island of Samarai, historic gateway to the old British Protectorate, as the guest of the benign grandson of a cannibal. He explores the former capitals of German New Guinea and headquarters of the disastrous New Guinea Compagnie, its administrators decimated by malaria and murder. He travels along the inaccessible Rai Coast through the Archipelago of Contented Men, following in the footsteps of the great Russian explorer ‘Baron’ Nikolai Miklouho-Maclay.The historic anthropological work of Bronislaw Malinowski guides him through the seductive labyrinth of the Trobriand ‘Islands of Love’ and the erotic dances of the yam festival. Darkly humorous characters, both historical and contemporary, spring vividly to life as the author steers the reader through the richly fascinating cultures of Melanesia.‘Beyond the Coral Sea’ is a captivating voyage of unusual brilliance and a memorable evocation of a region which has been little written about during the past century.Note that it has not been possible to include the same picture content that appeared in the original print version.

BEYOND THE CORAL SEA

Travels in the old Empires of the South-West Pacific

MICHAEL MORAN

Dedication (#ulink_2b6b7499-2270-5f7d-ba2b-8ec1b19f4a50)

For my mother who saw this voyage begin but not end and the children of Papua New Guinea so full of energy and eternal delight

Epigraph (#ulink_2df8e2be-2877-51f2-94f6-6d362cdbf5ee)

I have always thought the situation of a Traveller singularly hard. If he tells nothing that is uncommon he must be a stupid fellow to have gone so far, and brought home so little; and if he does, why – it is hum – aya – a tap of the Chin; – and – ‘He’s a Traveller.’

WILLIAM WALES

Astronomer and Meteorologist

Captain Cook’s Second Voyage in the Resolution

Journal 13 May, 1774

Contents

Cover (#u3a514cd1-60de-5a5b-ac30-13202fb88cb7)

Title Page (#u91ce298e-2f10-5d41-b212-de212beb2c34)

Dedication (#u938833f6-ece5-5ef2-a118-7754b6db55be)

Epigraph (#uecb18b7f-6343-549f-8e5b-a27e26e6bc47)

Maps (#u848ccf5a-5780-5427-94c4-a28caac449b1)

Prologue (#u7fd44c93-ab67-57ee-aa9e-c89db70ed64d)

1 Forsaking Pudding Island (#u21d29fc5-18e2-5107-be86-73760d26d4bb)

2 The Eye of the Eagle (#ua737560c-1715-591a-a39c-dee3211b8093)

3 ‘No More ’Um Kaiser, God Save ’Um King’ (#u959e3854-2690-5fc1-86ce-d4143f6f1519)

4 Death is Lighter than a Feather (#u9f8ef1c1-4fbf-5e33-ac2d-05e76c602374)

5 Too Hard a Country for Soft Drinks (#ua7162253-8717-5867-8428-2e2f2bf70828)

6 ‘Mr Hallows Plays No Cricket. He’s Leaving on the Next Boat.’ (#u7000a60e-2161-56a2-8300-db1afbe5f74b)

7 Constitutional Crisis in Makamaka (#litres_trial_promo)

8 ‘O Maklai, O Maklai!’ or The Archipelago of Contented People (#litres_trial_promo)

9 Kolonialpolitik Defeats the Man from the Moon (#litres_trial_promo)

10 Minotaurs on Gilded Couches (#litres_trial_promo)

11 Feverish Nightmares (#litres_trial_promo)

12 Grand Opening – Tsoi Island General Store (#litres_trial_promo)

13 An Account of the Criminal Excesses of Charles Bonaventure du Breil (#litres_trial_promo)

14 ‘In Loveing Memory’ (#litres_trial_promo)

15 ‘The Sick Man Goes Down with the Plane’ (#litres_trial_promo)

16 ‘Rabaul i blow up!’ (#litres_trial_promo)

17 Queen Emma (#litres_trial_promo)

18 A Moveable Feast (#litres_trial_promo)

19 ‘No Trespassing Except By Request’ (#litres_trial_promo)

20 Auf Wiedersehn, Kannibalen (#litres_trial_promo)

21 Under the Mosquito Net in Malinowski’s Tent (#litres_trial_promo)

22 Farewell to That Strange and Fatal Glamour (#litres_trial_promo)

Epilogue (#litres_trial_promo)

Afterword (#litres_trial_promo)

Brief Chronology of Significant Historical Events in Papua New Guinea (#litres_trial_promo)

Bibliography of Principal Sources (#litres_trial_promo)

Index (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

Author’s Note (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Maps (#ulink_1b7f493b-7106-59f9-8af2-239b139b6c10)

Prologue (#ulink_a0d1d0a0-37b1-5a09-87e1-046b4f0187da)

‘If you dress well, they won’t eat you!’ Wallace said.

He shuffled the cards with the stump of his right arm, beginning another interminable game of patience. The light was failing, the atmosphere oppressively hot and humid as the cards flapped on the bare table. Local boys glanced in darkly as they passed the flyblown screens covering the louvred windows. They were interested in the visitor and craned for a better view. A wretched poster of Bill Clinton greeting King Harald V of Norway hung at a crazy angle from the flaking wall.

‘We thought you were Gods.’

His rippling, grey hair caught the sun and he smiled, teeth showing the past ravages of chewing betel nut. Wallace Andrew was a distinguished personage with a heart of gold. This virtue had brought him many misfortunes in life. He began to hum the hymn ‘All Things Bright and Beautiful’.

‘Such a lovely tune, don’t you think? Young people today have abandoned proper hymns.’

The ceiling fan was motionless, the air thick and still. A pretty village woman with an ancient profile began to hurriedly set the table for dinner, laying out cutlery, bananas, pineapple and some lurid green cordial in a glass jug. She covered it with mesh. Malarial mosquitoes had already begun to ride the last shafts of sunlight in the dusk. ‘Napoleon will be here at seven. They will come directly from the chamber and then go out again,’ she said in excellent English, clearly for my benefit. They generally spoke the Suau language in the islands around Milne Bay in Eastern Papua New Guinea.

‘Fine men. Like my grandfather, a fine man,’ Wallace noted sadly, another fast game of patience in progress in the gloom. He adopted a consistently high moral tone in all his conversations and talked often of selfless Christians.

‘Charles Abel, one of the first English missionaries, always wore a bow tie, white shoes, starched shirt and trousers. He was never kai kai’d

(#ulink_c7e5ceaf-fa6d-577c-a1e6-469d58ba8216) because they respected him. His wife came from England too. She delivered a village baby after they landed and her white dress was soon covered in blood. They didn’t eat her. She helped them.’

Wallace was, after all, the grandson of a cannibal and an expert on matters of cannibal etiquette.

Two men carrying folders dragged open the grill on the front door and entered the main room. They glanced quickly and expectantly at the deserted bar but it had been some time since any festivities of an alcoholic or social kind had taken place there. They greeted Wallace. He stood up full of respect and pleasure that government ministers had chosen to be guests at his establishment.

‘We go up, then come down to eat, then go out.’

The brevity of their speech was almost aggressive as they noticed the white stranger in their midst. The assertive masculinity of Melanesian culture. Their dark features could scarcely be seen as they climbed the central flight of a once-grand staircase that branched into two wings of remarkable austerity and dilapidation. Their bare feet made only the slightest sound like large cats padding about. Floorboards creaked overhead and doors slammed. Silence apart from the worn cards softly slapping one over the other. Wallace scarcely glanced at the deck as he deftly adjusted his amputated arm, leaning slightly to one side, gathering them in.

‘You can walk around the whole island in the moonlight. It’s beautiful. Even if you are drunk nothing will happen to you here – not like the hell of Alotau!’

Wallace was full of trust in his fellow man yet he had suffered many betrayals. Tropical foliage spun by the moon appealed to my sense of romance, but this particular night was pitch black.

Fluorescent lights cruelly illuminated the dining room. The Kinanale Guesthouse was in desperate need of refurbishment. During colonial days it had been the single accommodation for white employees of the Steamships Trading Company.

(#ulink_100ac32f-7377-5151-a421-c7248013e6cf) Paintings of sailing ships and bush huts with strange watchtowers covered the larger cracks. A small lounge opened off the main room like a builder’s afterthought. Geckos darted in erratic motion across the stained walls. Dinah removed the mesh from the table. She laid out fish and taro on platters together with a jug of crystalclear iced water. A solitary bell sounded the hour over the football pitch, former cricket ground, former malarial swamp that lay before this once select building in the centre of the island. An air of abandonment and futility gave rise to a curious sense of threat and lethargy.

The government officials had changed into crisp shirts for the evening session and padded over to the table. Wallace, perhaps sensing their shyness, decided to introduce me.

‘This is Mr Michael from England. He is a famous man and wrote me a letter,’ searching the while in a battered briefcase. He produced the creased relic and began to read out loud, to my acute embarrassment. ‘Dear Mr Andrew, your name was given to me by Sir Kina Bona, the High Commissioner in London and I …’

Their fierce expressions changed at once to broad smiles of extreme friendliness. But the visitors must always make the first move.

‘Wallace has been telling me all about your important government work. What are you doing on the island?’ I was tactfully pouring a glass of the luminous cordial so as to avoid appearing overly inquisitive. Wallace beamed from his proprietor’s perch.

‘I’m Napoleon, Assembly Clerk for the Milne Bay Province and this is the Principal Adviser to the Provincial Government. He’s from Morobe Province. We are running a seminar for local councillors. Welcome to our difficult and beautiful country.’ The introductions seemed overly formal, even odd, in this place that had clearly seen better days.

I was on Samarai, a tiny island in China Strait that lies off the southeastern tip of Papua New Guinea, described before the Great War as ‘the jewel of the Pacific’. It was the original port of entry to British New Guinea and had been the provincial headquarters before Port Moresby. This gem lay on the sea route between China and Australia. The tropical enchantment cast by Samarai was loved by all who visited it. Destroyed by the Australian administration in anticipation of a Japanese invasion that never happened, it was now more like the discarded shell of the pink pearls still harvested nearby.

Having dinner with the descendant of a cannibal, a man who spoke reverentially and compulsively of the shedding of the blood of Christ whilst humming ‘All things bright and beautiful, all creatures great and small’, was just the beginning of a cultural adventure through the largely unknown islands of Eastern Papua New Guinea.

(#ulink_5149af18-9db0-5657-ba5e-efa7d3c8e965)Pidgin for ‘food’ is kai kai. Here it is used as a passive verb – to be kai kai’d is to be eaten.

(#ulink_7853dd16-bcca-5c2b-b9d9-fb8182c7e89a)Steamships Group is one of the largest public companies in Papua New Guinea with many diverse business interests apart from shipping. The original Australian company was established in adverse circumstances in Port Moresby in 1924 by a retired sea captain, Algernon Sydney Fitch, the first branch opening on Samarai in 1926.

1. Forsaking Pudding Island (#ulink_94128a05-1908-5162-9152-06d4474ac7fc)

London

29 September 1999

It was raining heavily as I clambered out of the taxi in the Mall and ran up the grand flight of steps past the Duke of York column into Waterloo Place. The statues of the explorers Sir John Franklin and Captain Scott looked stern and Olympian. I was heading for the High Commission of Papua New Guinea through a forest of history and high culture, umbrella up, head down. The high classicism of Nash’s Via Triumphalis, former site of the Regent’s wanton and ruinous Carlton House, could not have contrasted more strongly with the musky odour in the corridor of pagan carvings that led to the High Commissioner’s office. Grimy windows overlooked Waterloo Place. The national flag wrapped around its pole badly needed cleaning. Papua New Guinea time and GMT were indicated by rough signs on mismatching clocks. This was clearly the lair of a culture unconcerned with cosmetic niceties. His Excellency Sir Kina Bona, the High Commissioner, was chewing gum and watching the Rugby World Cup as I wandered in. He had an instantly likeable face and seemed unaffected by his diplomatic status.

‘How do you do, sir?’ I held out my hand respectfully.

‘Much better if I could get out of here mate! Do you like rugby? What can I do you for?’

The gum thunked into the bin. Rugby was the furthest thing from my mind, but this was a promising beginning. He had a refined, educated air and wore fine-rimmed glasses. Underneath the banter I felt a moral outlook at odds with the modern political world.

We sat down and began to talk. An islander from Kwato in Milne Bay Province, he had attended the mission school as a child, secondary school in Sydney, studied Law at the University of Papua New Guinea and was Crown Prosecutor at the Public Prosecution Office until 1994 when he was subsequently appointed to the post of High Commissioner. Married to a ‘Lancashire lass’, he should have left London two years ago.

‘Britain has little interest in PNG but all the Commonwealth High Comms cooperate very well.’

Grotesque Sepik river masks grinned down like a nightmare from another world.

‘Where are you off to?’ he enquired vaguely, settling uncomfortably into a leather chair.

‘I’m planning a trip around the islands next year. I don’t intend to go to the Highlands at all. Far too violent. Just the islands.’

‘Yes – the violence. Moresby is pretty bad. The police are so under-funded that corruption is rife … the jungle hardly lends itself to strict policing. Not like Surrey!’

He laughed with a hint of derision at the ease of civilised life.

‘I used to live on Norfolk Island off the coast of Australia. Home to the descendants of the Bounty mutiny.’

I was fighting to establish a rapport with this fellow islander, some common ground. The masks seemed threatening in Waterloo Place. The contrast was suffocating.

‘Really? Islands are special places. I miss the sweet waves of Samarai and Kwato on moonlit nights. Cities, well …’

He drifted off into an unexpected romantic reverie. I explained myself.

‘I got bored with catching the seventy-three bus down Oxford Street to Victoria every morning. Threw it up in the end. The job I mean.’

‘What were you doing?’

‘Teaching languages.’

‘I had fine English teachers at the Mission. The very best.’ He paused. ‘Now we only bash the missionaries during election time!’ He grinned broadly.

After some desultory chat about the independence movement in East Timor and the excitement of family life in Hampstead Garden Suburb I rose to leave.

‘I’ll send you some family contacts and useful people to look up. They’ll look after you, or eat you!’ More good-natured laughter.

I signed the visitor’s book and left the office. I was heading for Berry Bros in St James’s to collect a good bottle of red Graves. A final farewell to civilisation. A feeling of exhilaration passed over me as I glanced back through rain-lashed Waterloo Place at the windows harbouring that alien world. For a moment I watched the beads of water running off the polished bonnet of his midnight-blue diplomatic Jaguar.

I was about to escape from Pudding Island.

The original idea of sailing a copra schooner called Barracuda around the islands of Eastern Papua New Guinea in the spirit of Robert Louis Stevenson had faded, as do so many boyhood dreams. I. had always wanted to sail the old vessels of the past on those remarkable voyages of discovery. My friends at the Royal Papua Yacht Club laughed at the idea and told me that all the old ketches and schooners had rotted in the mud. The price of copra had collapsed and the corpse of the industry was barely twitching. No one would dream of wasting money building or even repairing an old copra schooner. There were no more sailing ships plying the islands. Traditional sailing canoes like the majestic lakatoi of Port Moresby with their towering crab-claw sails and multiple hulls had by now almost completely disappeared. Chartering a vessel as an individual was prohibitively expensive. Even if I had sailed my own yacht I could easily become a victim of unfavourable trade winds or worse, piracy. Unless I was prepared to wait for unreliable boats from Thursday Island in the far north of Australia, it was impossible legally to enter Papua New Guinea except by air through Port Moresby or Mount Hagen in the Highlands. I was disappointed but determined to sail at least part of the Australian coastline in the old style, completely dependent on the vagaries of wind and weather.

A rare opportunity arose to ‘take passage’ on the replica of Captain Cook’s ship Endeavour as a supernumerary member of the crew. That it was sailing in precisely the opposite direction to my intended destination did not disturb me. I would experience sailing a tall ship along the New South Wales coast for a week from Southport (near Brisbane) to Sydney. A suitably nautical frame of mind would then enable me to jet off to Port Moresby with equanimity.

Endeavour is a handsome vessel and a magnificent replica of the original ship. It was constructed as Australia’s flagship from 1988–94 in Fremantle in Western Australia. She is built of jarrah and has upper sides of varnished pine, finished in the Royal Navy colours of blue, red and yellow. I took Sir Joseph Banks’s cabin on the after fall deck – a small space that I later discovered was occupied not by Sir Joseph himself but by his dogs – a bitch spaniel called Lady used as gun dog, and a greyhound taken on board to run down game.

Joseph Banks was only twenty-five when word reached him on 15 August 1768 that Endeavour was ready to take him aboard on a great adventure to the South Seas. He was at the opera in London with Miss Harriet Blosset, a French ward to whom he was engaged and in love, but with whom he lamentably lacked the French language to communicate. Confessing himself to be of ‘too volatile a temperament to marry’, and unable to explain the meaning of his imminent departure, he drank heavily in a romantic funk the night before he left London for Plymouth. Poor weather delayed the sailing until 25 August.

Banks’s father was an MP and the family were wealthy and well-connected, living at Revesby Abbey in Lincolnshire. He had been to Eton (which trained him no doubt for the rigours of the voyage but not for the travails of love), spent seven years at Oxford studying botany, and worked at the British Museum in London. In February 1768, the Royal Society decided that observing ‘the passage of the Planet Venus over the Disc of the Sun … is a Phaenomenon that must … be accurately observed in proper places’. The Admiralty decided on Tahiti as a place of observation, and James Cook was appointed chief observer of the transit. He selected a Whitby ‘cat’

(#ulink_35b09695-abb7-5ca1-a3ad-25b8f3a8a004) called the Earl of Pembroke as the most suitable vessel for such a voyage, refitted and renamed her the Endeavour.

As a Fellow of the Royal Society, Banks contributed ten thousand pounds to purchase a vast quantity of both practical and elegant equipment for the voyage, and transported a comprehensive library of some one hundred and fifty volumes. A party of nine made up his gentleman’s entourage, all trained in the techniques of collecting and preparing specimens. He became almost more famous than Cook himself, but remained dogged by the unfortunate repercussions of the ‘caddishly abandoned’ Miss Blosset (‘Miss Bl: swooned &c’, his journal coolly observes).

Cook had a complement of some ninety-four souls together with chickens, pigs, a cat and a milch goat that had already circumnavigated the globe. In a letter to Banks in February 1772, Dr Johnson included a Latin elegy for the celebrated animal, part of which runs:

In fame scarce second to the nurse of Jove,

This Goat, who twice the world had traversed round,

Deserving both her master’s care and love,

Ease and perpetual pasture now has found.

His adventurous friend James Boswell records that Johnson was sceptical of what a traveller might learn by taking long voyages, despite on one occasion when dining with the Reverend Alexander Grant at Inverness, divertingly ‘standing up to mimic the shape and motions of a kangaroo’ and making ‘two or three vigorous bounds across the room’.

By 16 August 1770, Cook had reached the Great Barrier Reef, courageously searching for the elusive passage between New Guinea and Australia. The passage had originally been discovered in 1606 by the great Spanish navigator Luis Vaes de Torres, but strategic secrecy was paramount for Spain and on many charts the two land masses appeared joined. Capricious winds drove Cook and his crew ineluctably towards disaster. ‘… a speedy death was all we had to hope for …,’ reiterated Banks. But by 21 August, the Endeavour had threaded its way around Cape York, the northern extremity of Australia, and passed through the Endeavour Straits or as it is now named, Torres Strait.

On 27 August they set sail for New Guinea. They voyaged past the south coast of the island, almost a year now after the visit to Tahiti where the officers had observed the transit of Venus and Mr Banks the slow and painful tattooing of a girl’s bottom. Two days later they came to a landfall fringed by dense vegetation and mangrove swamps. Banks wrote: ‘Distant as the land was a very Fragrant smell came off from it realy in the morn with the little breeze which blew right off shore …’ The water was warm, muddy and shallow, keeping them away from the coast until 3 September when they waded in to land. Banks collected a few specimens but remained curiously unimpressed. They found human footprints which caused them as much consternation as that felt by Robinson Crusoe. They proceeded with caution until they came to a hut in a grove of coconut palms. Three warriors suddenly rushed them from the jungle, throwing spears and incendiary devices, shouting hideously. A hundred naked Papuans appeared around a promontory. It was time to leave.

The following excerpts are taken from my voyage diary:

Endeavour, 7.30 p.m.

4 September 2000

Have come off Afternoon Watch and had dinner. A nerve-wracking and terrifying day. Rose early 6.00 a.m. Troubled sleep – excitement, nerves and information overload. Claustrophobia with the cabin door shut. Prolix talk of ‘bunts’, ‘clews’, ‘belaying lines’, ‘bracing the yards’ and generally hauling on any of the innumerable ropes in sight. Mind-snapping terms of the sea is assumed knowledge – understood absolutely nothing.

Time to ‘go aloft’. Terrified. My group designated Foremast Watch. Forced by bravado to climb the ‘ratlines’. Felt decidedly like a rat. The lines are angled up to a platform called the ‘tops’. Remainder of the thirty-three metre mast towers above. Palms sweating. Shuffling along the yard (to which sails are furled) on rope not much thicker than a garden hose. ‘Stepping on!’ is the brisk instruction. ‘Falling off!’ screamed as you crash to the deck. Managed that, then. Is this my future for the next seven days? Much preparation casting off.

Very calm day, brilliant sunshine with light NE wind.

‘Stand by for cannon!’ shouts the ship’s carpenter, a handsome, blond Cornishman, responsible for construction of the replica and loved by all the girls.

‘Fire in the hole!’ He lights the powder.

Boom! Replica four-pounder carriage gun recoils, acrid smoke rolls across the deck. A terrific report, too close to some nautical types sipping Pimms on the deck of their chromium cruiser. They fell backwards off their chairs as shredded paper and smoke engulfed them.

‘Haul on the halyards! Ease on the bunts and clews!’

Felt like easing myself but not permitted until further out. Hauled on lines until palms sore. Not seasick but a visit to the heads (mariners’ term for onboard toilet) could bring it on. Open grey valve, pump up water, do your business, keep your balance as you have a good look while you pump out, repeat three times, close grey valve under pain of castration. Voyage will be no picnic. Comforting smell of tar.

Came off Afternoon Watch at 4.00 p.m. and resume First Watch at 8.00 p.m. Ship glides slowly and is deeply restful. In perfect harmony with the sea. Progress about 3 knots – a stately speed which would have given Banks and his party ample time to draw, read, discuss and describe their collections. Sun setting through the stern sash windows of the Great Cabbin. Storm lanterns lit, secretive plashing of water at the stern and creaking of the ship. Absolutely magical and poetic.

Sailing at night on the Endeavour is like taking part in a Wagnerian opera, the Flying Dutchman, perhaps. On watch, time to gaze up at the moon through the swaying rigging, silhouetted against the myriad stars of southern latitudes. A shadowy helmsman guides us across the deep. Silence on deck. Ship groans quietly as it folds through the sea. Watching the phosphorescence at the bow I was suddenly transfixed by the appearance of silver tunnels and comet trails cut by porpoises as they dodged and played before the ship. Captain ordered us to ‘wear ship’ – rudely-broken reverie. Had to set the sails and belay lines (fasten the coils of rope around wooden pins) in the dark. After stress and furious activity, lying on my back in front of the helm watching the masts arch like giant pointers across the constellations. Dreamed of the discovery of New Guinea on a ship such as this.

Endeavour

6 September 2000

Morning Watch began at 4.00 a.m. Ungodly hour to be on deck. A still night with feathery winds and countless stars, the moon intensely bright. Silhouettes of the crew on watch float like wraiths. Dawn a glowing rind of orange before sun breaks the horizon. Red Ensign flies from the stern mast and stern lantern glints in the dawn.

Later in the morning a hump-backed whale breached – spectacular arch of patent-leather black and white. Barometer falling. ‘It’s coming all right,’ crackled Captain Blake ominously on the weather deck. During night watches he often comes on deck bare-chested in a maroon sarong. Seems to sense any unnatural movement of the ship through his sleep. Catapults from the companion to bark orders in eighteenth-century style.

Mainmast Watch took in sail at Trial Bay off coast of New South Wales. Landing from surf boats. Moving reconciliation ceremony with Aboriginal community. Exhausted from climbing and hauling – aching and stressed by vast quantity of strange sailing nomenclature.

Endeavour

7 September 2000

Oppressive lowering sky and ominous calm. Hardly slept for last three days. On watch and took the ‘brains’ side of the wheel.

(#ulink_b738013c-d3a7-51f8-b780-4569ec9187ac) Wind strength increased towards evening, gusting to 40 knots. Bow ploughed into the 1.5m swell but the ship felt strong. Sea a magnificent expanse of breaking waves, wind tearing the lashing foam. Shrieks rent the rigging. Wheel duty in this weather madly exhilarating. Maintaining course fraught with problems, arms aching, slow response to helm. Bow rises to frightening heights before ploughing back down into the troughs.

Lines lashed. Many seasick. Going aloft 25 metres in these conditions to take in t’gallant sails not for the fainthearted. Respect for the old mariners boundless – their achievement unimaginable until you sail a tall ship. Vessel utterly at the mercy of wind. So tired cannot sleep. Eating little.

Great Cabbin, Endeavour

8 September 2000

Physically impossible to write. Force 8 gales. Taking in all sail. On verge of throwing up. Gorge rising. Ship lurched and shuddered through night. Roped myself into the fixed cot.

Endeavour

9 September 2000

Wind sufficiently abated to write a journal entry. Warm sun as we sail along the coast of New South Wales and begin to set sails again after the storm. Activity everywhere.

‘Hauling on the halyards! Easing on the bunts and clews! Bracing the yards!’

‘Two, six … heave!’ we hauled on the lines.

‘Two, six … heave!’

‘Belay all lines.’ Signs of relief.

Leaned against the capstan and idly looked at a jetliner high above, slicing across the sky leaving a glittering trail of ice crystals; the eighteenth century contemplating the twenty-first century. The original exploration of the Black Islands of New Guinea was on ships such as this. My own journey to that fabled land would be on an aircraft such as that.

(#ulink_03a71e18-255d-5412-9a95-3be575c9efa4)The English north-country vessel known as a ‘cat’ was a Whitby collier. This was the type of working vessel on which James Cook learnt his calling. In 1771 he wrote in admiration of her handling, ‘No sea can hurt her laying Too under a Main Sail or Mizon ballanc’d.’

(#ulink_e09f5e66-cd1e-5cd1-ae3e-554d33b36a2e)Two seamen are normally at the wheel – the ‘muscles’ on the port side who only helps turn it, and the ‘brains’ on the starboard side who turns and maintains the course, calling out the setting and watching the instruments.

2. The Eye of the Eagle (#ulink_738ef638-7ebc-5b8f-bf85-658735a38dcf)

Final approach to Port Moresby in the dry season is over arid, brown hills bereft of vegetation and a polished turquoise sea. The colonial terminal at Jacksons airport has faded lettering on the fibro huts, the modern terminal a bland feel, new paint already peeling in the heat. An Air Force Dakota without engines lies abandoned on one side of the runway, a reminder of the first commercial flights. The blast of desiccated air as you disembark is like a physical punch, gusts of the south-east trades dry the mouth. Certainly you are no longer referred to as masta as your bags are unloaded. Only one officer is on duty at passport control to process the entire jetload of passengers. Welcome to modern Papua New Guinea, ‘land of the unexpected’.

Captain John Moresby may have been the first white man the native people had ever seen when he sailed into the harbour aboard the HMS Basilisk in 1873. He spent some time trading with the villagers of the local Motu tribe. He wrote that civilisation seemed to have little to offer this culture. The London Missionary Society were settling in a year later and by 1883 there were five resident Europeans in Port Moresby including the Reverend James Chalmers, a gregarious character who was eventually murdered and eaten by cannibals on Goaribari Island in Western New Guinea. Despite its isolation and absence of road connections, Moresby has remained the capital.

The taxi driver informed me that the bullet hole in the corner of the cracked windscreen was from raskols – a misleadingly benign Pidgin word meaning ‘violent criminal’. They had attempted to hold him up on the way to ‘Town’, the centre of the city. He was a Highlander with an ambiguous smile somewhere between a welcome and a nasty threat. I began to glance anxiously at passing cars.

‘Wanpela sutim mi nogut tru lon hia. Olgeta bakarap.’

(#ulink_ac06590d-d025-531f-9ed1-18ad2ca409b7)

‘Were you hurt? Did they take your money?’

‘Took everything but I drive away quick. Back at work next day. Mosby em gutpela ples.’

(#ulink_0884e5e8-5933-5e6c-8370-edee647c2f0c)

This made no logical sense at all to me so I fell silent until we reached the hotel. It was a dusty drive with colourful children and resentful adults crowding the roadsides. There had been a drought for the last seven months. The usual Western corporate signage had been bleached by the savage sun. A car had collided with a truck bearing the company name ‘Active Demolition’. I glimpsed the original Motuan stilt village of Hanuabada, fibro huts replacing the traditional bush materials. A few cargo ships lay becalmed in the port.

A midday stroll among the sterile office blocks, slavering guard dogs and confectioner’s nightmares thrown up by financial institutions did not appeal, so I headed south for Ela Beach, an inviting stretch of sand facing Walter Bay. Trucks cranked past with men crammed like sardines in the back and small PMV

(#ulink_27f60bc0-c7df-560e-944e-06a5b20b3c50) buses smoked happily by like toys. Seaweed, cans and other detritus marred the shore, but kiosks gaily painted in Jamaican style lifted the spirits. A rugby side were training on the sand, running forward through a line of plastic traffic cones and then suddenly reversing through them. Many who were overweight fell over during the difficult backward manoeuvre but there was no laughter, just embarrassment. Papua New Guinea is the only country in the world that has rugby as its national sport and every aspect of it is taken seriously. Training was interrupted by the capture of a turtle on the breakwater. A long time was spent inspecting and discussing the prize. Some of the boys scribbled graffiti on its shell in luminous paint and then released it back into the bay, fins flapping, neck craning. Training resumed.

Palm trees with slender trunks curved over the bay in front of international high-rise apartments. I walked past a group of suspicious-looking youths sitting under some trees outside a café and strolled out onto the disintegrating breakwater. A family were competing with each other, skimming pebbles across the surface of the water. The five children, father and mother were screaming with delight at this simple game that seemed to bond them so intimately.

Visitors are warned by expatriates not to approach, in fact to walk away from groups of youths but I decided to wander over to the cluster beneath the casuarina trees. They were chewing betel nut and spitting the blood-red juice in carefully-aimed jets. They were shocked when I greeted them, but smiled almost immediately. The smile on a Melanesian face is like the unexpected appearance of a new actor on the stage.

‘Monin tru, ol mangi. Yupela iorait?’

(#ulink_c5990bb4-8e30-5fd2-9be3-dd62ec5b9c28)

‘Orait tasol, bikman.

(#ulink_6098a156-7483-537b-a0c8-a4dce162a775) Where do you come from?’ They stood up, even respectfully I thought.

‘England. I live in London. My name’s Michael.’ I held out my hand which was shaken softly. They shuffled about looking at the ground, showing signs of amazement by spitting fast red gobbets in the dust.

‘And you’ve come here! Do you like our country?’

‘Everyone seems pretty friendly to me. What’s your name?’ I asked a boy with the most intense black skin I had ever seen – it was almost blue. He had dreadlocks, perfect white teeth and eyes like an eagle. He appeared highly intelligent, but melancholic shadows fleetingly crossed his features.

‘Gideon. I’m from Buka.’ His open face smiled engagingly.

‘Really! I hope to go there. I’m visiting the islands.’

‘It’s beautiful on Buka, but no work. The Bougainville war destroyed everything. I came to Moresby but can’t get a job. I’ve got my electrician’s certificate.’ The shadows were well established.

‘Mipela ino inap lon bikpela skul,’

(#ulink_27b38975-1789-554f-8622-24c28b44fca0) said a fierce lad with broken, heavily-stained teeth. It looked as though a bomb had gone off in his mouth. He was angry.

‘I come from the Sepik. I have no parents and no money.’ He looked savagely at the ground and started violently peeling a new nut.

‘Are you all unemployed?’ I asked, already knowing the answer.

They nodded dreamily.

‘Don’t you miss your family?’

Silence.

‘I’ve heard that some boys break into houses and steal. Is that true?’ I was living dangerously, considering it was my first afternoon.

‘Yes, but they’re not bad boys, sir. We’re not raskols! We need the money to eat. We want to work but we can’t get a job.’

‘That’s not really a good reason to steal. You could go to prison. Ruin your life.’

‘Corrupt politicians have ruined our country. You don’t see them going to prison.’ Gideon offered this as a challenge for me to refute.

‘No one gives us a chance. We’re on the outside looking in.’

‘Where are you from?’

‘Chimbu.’ The older man seemed to stand apart from the rest and was more deeply resentful.

‘Where do you live in Moresby?’

‘Are you a priest?’ It was an aggressive answer. ‘Ragamuga. Six-Mile Dump. You’ll visit?’ He smirked and spat into the dust. I had only read about this desperate migrant settlement situated behind a large rubbish dump. No, I did not intend to go there.

‘But what about your future?’ I was moving into a dead-end.

‘So? No one gives a shit about us. Politicians just want money.’ Isaiah was from East New Britain and had parallel tattoos on his cheeks.

‘We’re bored and no future. That’s the problem.’

I realised with alarm that my group had grown into a small crowd that surrounded me. They pushed forward not to attack but desperate to explain, to justify themselves, expecting me to provide an explanation, an instant solution.

‘Everyone hates us. No tourists come because the newspapers report so much violence.’

I said nothing but the headline in the newspaper in my hotel screamed of the rape of three nurses at Mt Hagen Hospital and the theft of an ambulance. The thieves were demanding compensation for the return of the vehicle or they would torch it.

‘Violence is terrible in the Highlands. That’s why I chose the islands.’ I was out of my depth.

‘You’re lucky. You have money to travel,’ said a boy from Oro Province wearing a bedraggled feather in his hair.

Beavis and Butthead cartoons flickered on the screen behind the heavily-barred windows of the ‘Jamaica Bar’. Papuan reggae music was playing somewhere. I was a distraction but not a solution. Some drifted away and sat under the trees again. Large spots of rain from an afternoon storm kicked up the reddened dust.

‘Well, I’d better be going. Nice to have met you. Gideon, Isaiah …’ I shook their hands.

‘Tenk yu tru long toktok wantaim yu, bikman.

(#ulink_d3b9b5e9-04d1-5fee-8194-66c2c2192a0f) All the way from London! Enjoy our country.’

They remained standing and smiling as I headed back. This encounter with wasted potential, cynicism, and the crushed optimism of youth left me feeling depressed and impotent. The cultural diversity of the country meant that there was tension between youths from many regions thrown together by unemployment. In traditional villages in the past, fear of neighbouring peoples and respect for the authority of the elders would have limited the freedom of the young. The notion of respect had almost disappeared, but not only in Papua New Guinea. London and Sydney were similar, but this country was poor and the politicians corrupt.

Many observers blame the present law and order troubles on the premature commitment Australia made to the granting of independence in 1975. At the outset, an inappropriate West-minster-style two-party democracy was imposed on the country with legislative power vested in a national parliament. The national government devolved power through nineteen provincial governments. The country joined the Commonwealth with the Queen as Head of State, and a governor-general appointed as her representative. Papua New Guinea covers a vast area (it is the second largest island in the world) and possesses such extreme cultural diversity that the growth of a properly integrated strategy for development has remained a perennial challenge. The first Prime Minister, Sir Michael Somare, was an able and popular politician, but the many emergent parties have become increasingly unable to establish clear ideological principles. Political candidates pursue personal or regional goals at the expense of party policies.

(#ulink_fd6bfd63-2f1a-5389-997d-f37777946891)

Most Papua New Guineans still live a subsistence lifestyle in villages quite separate from the influence of the cash economy. The villagers have become convinced that, at both the provincial and national levels, politicians are self-serving and uninterested in their welfare. Traditional social arrangements had already begun to disintegrate under colonial rule. The adoption of an inappropriate Western legal system has only exacerbated the agony of cultural fragmentation. Tribal fighting has resumed in the Highland provinces, but under more murderous rules than in the past. As the traditional society in the village disintegrates, many young people flee to the urban ghettoes of Port Moresby and Lae to face almost certain unemployment followed by a descent into crime. The challenge remains to evolve a system that combines the strengths of traditional leadership with the ideals of modern government, giving due legal weight to the fraught claims of land ownership by the numerous clans.

On my return to the ‘executive floor’ of my hotel, I passed psychedelic kiosks and wrecked cars in the oppressive heat and scalding rain. Luxury expatriate enclaves seemed to be going up everywhere on higher ground. Segregation has made this a city divided against itself. The cool, spacious lobby transported me to a different planet to that inhabited by my ‘new friends’ on Ela Beach, and the grim reality of their settlement homes. This was the arena where exploitation and ‘aid’ were strategically planned by company generals. The sunset from the elevation of the executive floor was sublime; copper and tarnished brass shot through with blue. This luxurious scene was decidedly different from the wild 1920s when Tom McCrann’s hostelry in Moresby displayed a notice in the saloon:

Men are requested not to sleep on the billiard table with their spurs on.

At dinner there was an astounding mixture of guests. A tattooed Scot was having dinner with an Asian engineer.

‘Glad you’re on the fuckin’ project, Wang. You’ve got a degree.’

A German trio who had run out of time were attempting to negotiate a price for the ethnic decorations on the hotel walls. A heavily-tattooed Pacific islander in a black sleeveless singlet, chiselled black beard and jeans patched with grandmother’s chintz was eating soup and tugging at his pearl earring. A Belgian photographer with a ponytail was talking to a glamorous Parisian collector of artefacts from the Maprik region who had a gallery in Aix-en-Provence.

‘Every week I ’ave ze fever on ze exact same day!’ she exclaimed in desperation.

A newly-rich Highlander was eating a roast chicken, juggling greasy drumsticks in both hands and attempting to talk on a mobile phone. Pallid Englishmen and tanned Australians were earnestly discussing football and drink. They had the weak eyes and the furtive mouths of social casualties, bolstering their own false optimism or drowning betrayals in liquor.

‘The free drinks are from five thirty to six thirty. Don’t come after or we’ll have to pay.’

‘Right, mate!’

‘They’re tough men the South African rugby team!’

‘Blood oath! Fuckin’ tough!’

‘Hides like a rhinoceros!’

‘More like a fuckin’ elephant, mate!’

‘Fuckin’ tough.’

‘Yeah. Fuckin’ tough, real men.’

‘Fuckin’ tough!’

‘Yeah, fuckin’ …’ and so on, endlessly, whilst downing bottle after bottle of South Pacific lager.

A huge butterfly enamelled in iridescent blue battened against the glass door leading out to the swimming pool. A Chopin nocturne floated across the lounge from the Papua New Guinean pianist playing a grand piano. I wandered over at this unexpected appearance of European culture and spoke to him.

‘You’re playing Chopin,’ I rather pointlessly observed.

‘Yes. I studied classical music for many years. Do you have a request?’

‘Not classical. Jazz. Can you play “Misty”?’

‘Sure. If you like jazz you might like my novel. It’s on the music stand.’

A small pile of paperbacks entitled The Blue Logic: Something from the Dark Side of Port Moresby by Wiri Yakaipoko was stacked on one side above his fluent fingers.

‘What’s your novel about?’

‘It’s a crime novel about Moresby. Plenty of it around here to write about.’ I could hardly disagree.

Chopin, jazz and crime are an odd mixture. Unexpected conjunctions and unpredictable outcomes were to become a feature of all my travels in Papua New Guinea. I went to bed suffering from a blinding headache which seemed to come from the combination of the anti-malarial drug Lariam

(#ulink_a5850b26-1e16-59c8-8754-565b9683842f) and alcohol.

The next day the usual horrors were introduced quietly under the door of my room via the dailies.

A youth was chopped to death and two houses burnt down in the Kaugere suburb of Port Moresby over the weekend.

Under the banner headline ‘Patients Hungry’ we learn that patients’ food was stolen from Modilon Hospital in Madang.

A thirteen-year-old sex worker said, ‘My aunt kicked me out because she said I slept with her husband. Prostitution is fun and I get a lot of money.’ Tribal fighting now takes place with homemade guns, grenade launchers and Kalashnikovs rather than spears.

The city looks more attractive on my birthday. Red and mauve bougainvillea are flowering, Ela Beach looks inviting and the frangipani spiral down in pink and white. I decide to go for a walk. Outside the US Embassy I am almost arrested for writing down the sign NOKEN PARK LONG HIA meaning ‘No Parking’ in Tok Pisin (Pidgin).

The evolution of Melanesian Pidgin (or bêche-de-mer English, as it was popularly known in colonial days) was complex. There are many regional varieties of this colourful and witty language which originated on the Pacific plantations of Queensland, Samoa and New Caledonia in the early eighteenth century. It had emerged fully formed by about 1885 and is still evolving in rich referential complexity. Around eight hundred or one seventh of the world’s languages are spoken in Papua New Guinea. Some two hundred are Austronesian spoken in the coastal and island regions, and the remainder are Papuan spoken in the Highland areas. There are three lingua francas – English, Motu (spoken in Port Moresby) and Tok Pisin.

Outside the Westpac Bank a huge Alsatian and armed guard in a baseball cap stand in the centre of three signs warning ‘Beware of the Dog’. The brooding atmosphere of male unemployment hangs about like a miasma, and I have not seen a white face in three hours. Huge holes in the pavement and deep storm-water channels offer possibilities of serious injury. The light burst of a glowering Melanesian face suddenly smiling. At the Port Moresby Grammar School, children in pale uniforms are caged up in a security tunnel hung with plants waiting to go home. Fishing trawlers of unbelievable decrepitude are moored at the wharves. Thick, black smoke pours from their funnels, the idle crews lounging in the shade of tarpaulins or carrying huge tuna by the gills. One boy drops a plastic bag full of silver sprats that cascade over the wharf like pirate’s treasure. Six mothers breast-feeding babies inexplicably sit in the broiling sun on a concrete platform raised above a potholed road. I slip into the shade of the Port Moresby Public Library. An eerie silence reigns, but people greet my unexpected presence with smiles of surprise. Useful titles such as Australian Imperialism in the Pacific and Tuscan Cuisine grace the shelves.

A friend, John Kasaipwalova, had invited me for a birthday dinner. He is a prominent and controversial Papua New Guinean poet and writer and was a student rebel during the drive for Independence in the 1970s. He is also chief of the Kwenama clan on Kiriwina Island in the Trobriands, one of my destinations. I was collected in a Mitsubishi Pajero with gigantic bull-bars, a fantastically cracked windscreen and peeling sun filters. John has a round friendly face framed by a halo of tightly curled hair, his sensibility a rich repository of poetic image and symbolic knowledge. But entrepreneurial activities tend to preoccupy him these days, as he attempts to balance the claims of individual business and his responsibility to his own clan community. He was accompanied by Mary, his attractive Malaysian wife, and ‘Uncle Sam’, who drives the Pajero with fearsome spirit, thundering over unsealed roads past striped drums marking dark detours. While avoiding a cavernous pothole, he asked me to guess his nationality. His mother turned out to be from Sri Lanka and his father an unusual mixture of Dutch, Portuguese and Australian Aboriginal. ‘Dad’s family moved about quite a bit.’ Under an Australian bush hat he had the long grey beard of a swami and spoke with a slight Indian accent. It was a striking face, a colonial cocktail.

The shopping precinct that housed the Chinese restaurant was protected by a high security fence with bars two inches thick, armed guards, slavering dogs and a searchlight.

‘It’s a gourmet place!’ explained Sam as we parked among a crowd of children.

We were shown into a private room with intense fluorescent lighting. Geckos erupted into life on the walls like surrealistic wallpaper. Sam’s gold rings glinted on his slender fingers and the cutlery was reflected in his melancholic eyes.

Delicious coconut prawns, chilli crab and coral trout with tender asparagus appeared like magic. The conversation ranged lethargically over many topics, as if we were in an island village. They were shocked to learn of my walking alone in Moresby and even more surprised when I mentioned the young boys.

‘I’m hoping to go to the Trobriands quite soon, John.’ I briefly outlined my island itinerary.

‘You’ve made the best decision in choosing the islands. How come the Trobriands?’

‘Well, it’s a short story that’s taken a long time to complete. I bought a tabuya

(#ulink_234df5ba-8a26-55f2-a346-2b72c4630945) or wave-splitter from Kiriwina in an artefact shop many years ago. It’s been in my music room in London for ages, and I’ve always wanted to visit where it was made.’

‘I can tell you that the tabuya has been watching you. The design symbolises bulibwali or the eye of the sea eagle [osprey]. You had to come. His eye never sleeps, you know. In an instant he decided on you as his particular fish. That’s why you came. It’s very simple.’

‘Do you really believe this?’

‘Of course. You’re a person who possesses concentration. You plan and attend to detail. Am I right?’

‘Actually, yes. I drive people mad with it.’

‘There you are!’ John reached for more coconut prawns in an ebullient mood. He continued his arcane explanations with some seaweed poised between chopsticks in midair. I wanted to hear an account of the famous kula trading ring from the chief of a clan. I was anxious to know if the classical descriptions were still accurate.

‘Tell me something about kula, John.’

‘Well, first you must understand the mystery of Monikiniki or the Five Disciplines of Excellence.’

‘Sounds a bit complicated.’

‘Never! It’s simple! The disciplines are symbolised in the five compartments of a Trobriand mollusc shell. Each compartment represents one of the senses and is represented by a bird, plant or even a grasshopper. The eye is represented by the bulibwali or the sea eagle.’

We had moved into the realm of myth and magic for which these islands are famous, rather daunting for a European unused to the sharing of mystical experience.

‘But what is kula exactly?’ I was impatient as usual.

‘That’s not easy to answer, but basically it’s an activity of giving and receiving between people that results in them growing spiritually.’

‘But doesn’t it involve trading valuable soulava or necklaces in a clockwise direction around certain islands and mwali or arm shells in a counter-clockwise direction?’

‘Of course, but they’re only the outward manifestation of the activity, in fact the consummation of it. The objects accumulate power as they pass from hand to hand over time. Some might even kill you. But it’s the quality of this experience that’s important.’

I began to be drawn irresistibly into the rich mythological world of the Trobriand Islands, so unlike the sterility of my own empirical society where success seemed the sole criterion. I began to look forward to my trip with keen anticipation. A couple of lines of a poetic song concerning the kula came to mind.

Scented petals and coconut oil anoint our bodies We’re ready to sail with the south-east wind

John fell silent and took some more chilli crab. The mood had become serious yet our state of mind was happy and free.

‘I’ve never been to the yam festival in the Trobes. Never managed to get there. God knows why.’ Sam trailed off and adjusted his hat to a more comfortable position. He reached for some more coral trout.

‘God’s saving you, Sam, from a long period of self-abuse,’ John observed. Everyone laughed heartily. The yam festival is famous for its ecstatic expression of sexual freedom in celebration of the harvest and the end of ten months hard gardening.

Myth and magic give life meaning in the islands. We discussed the weighty word kastom. It is an essential Pidgin concept that derives from the English word ‘custom’ but with a more complex Melanesian meaning and multifarious connotations. It is normally used in reference to traditional culture that has come under threat from aggressive European development. But kastom cannot be simply translated. There are many contradictions within this multilayered concept. The idea has led to a strong cultural revival as regional identities become increasingly diluted. People are always talking about the loss of it. Closeness to nature and the traditional sense of belonging to a community are being replaced by the desire for individual consumption. European technology dominates modern life in the cities, yet a profound need remains for the unseen worlds of magic and religion. A further complication is the extreme cultural diversity of the country. Many distinct cultures have been wilfully cobbled together into the artificial political entity known as Papua New Guinea. Cultural differences are ignored, or worse, attempts are made to diffuse them.

‘More chilli crab?’ Sam spun the lazy susan.

‘Do you know there is a ruined temple on the top of Egum Atoll?’ John said, secretively.

‘Yes, and flat stones with magical properties on Woodlark Island,’ his wife whispered.

It was getting late. We emerged from the restaurant into the glare of security searchlights. The massive gates swung open and we drove out of the compound. Uncle Sam began to sing the praises of Port Moresby as we drove back into town. Mansions surrounded by high fences topped with glistening razor wire, signs painted with cartoon-like dogs and guards posturing with guns, spun through the headlights. Dark hills sprinkled with twinkling lights reared on either side of the highway.

‘Nothing is as beautiful as this in the world!’ Sam suddenly exclaimed with great feeling.

I spent a restless night poring over maps, anxious to leave the place. Papua New Guinea can be broadly divided into the mountainous interior, the coastal regions, great rivers and the island provinces. My decision to explore the islands had come from their extreme isolation, their reputation for beauty, tranquillity and the preservation of their ancient cultures. Near Moresby, the start of the Kokoda trail had been closed by tribal fighting. There were reports of a white, female bushwalker who had been raped even though she was with a local guide. This constant threat of violence in the capital had begun to depress me. I was tired of being holed up for safety in a luxury hotel with paranoid expatriate businessmen planning the disintegration of a culture for profit. My jumping-off point for the islands would be Alotau, the capital of Milne Bay Province at the eastern extremity of the mainland. From there I could leap aboard a banana boat

(#ulink_2591bbc4-0051-5238-8b96-7a6fb704a94e) to Samarai, the traditional gate to the old empires.

(#ulink_54086fc4-7196-5a0a-bc59-3787e645e701)‘Somebody shot at me. Everything around here’s pretty bad. It’s completely buggered up!’

(#ulink_326a351f-baa3-5919-993d-99075c56896a)‘Port Moresby’s a good place.’

(#ulink_ec877a61-a3ef-57c4-b655-4409ed6ce0b5)Public Motor Vehicle – these minibuses are considered to be dangerous for visitors, but in my experience they were a source of all my best conversations and friendships with local people.

(#ulink_d171a1b2-b897-58fc-a166-d242c7f36287)‘Good morning, boys. How’re you?’

(#ulink_6674fa73-7afc-5d4f-8000-897fb85f418b)‘Fine thanks, Sir.’

(#ulink_40540860-5002-5278-82d7-be09a241756c)‘We can’t afford university.’

(#ulink_7f762aef-b7ea-5da5-bd4e-c79911404690)‘Thanks very much for talking to us, Sir.’

(#ulink_64cd5c84-3fe1-52e0-9854-4bed3681ca17)Sir Michael Somare was born in 1936 in Rabaul, East New Britain. He led the Pangu Pati (Party), the largest and most influential political party in the move towards independence in 1975. He became the first Prime Minister of independent Papua New Guinea from 1975–80 and again from 1982–5. His membership of the Pangu Pati ended in 1997 and he formed the National Alliance Party which won a comfortable majority in the violent 2002 elections. After seventeen years, Sir Michael Somare, ‘the father of the nation’, was elected Prime Minister for a remarkable third term.

(#ulink_4df6f921-1f48-53ab-ae6d-59ee1841bef5)Mefloquine or Lariam (the trade name) is the most powerful of the anti-malarial prophylactics. Unlike other drugs, it protects against the fatal strain of cerebral malaria. It can have disturbing psychological side-effects.

(#ulink_6ccb450a-e4c8-5069-812a-db85d5eaee33)A tabuya is the prowboard of a Trobriand canoe.

(#ulink_69d7b43c-9010-5ac4-83b1-36dc300ab484)The term ‘banana boat’ has nothing to do with bananas or their transport. It refers to the shape of the innumerable fibreglass dinghies fitted with forty-horsepower outboard motors that ply the islands and coast of PNG like noisy water insects. They have taken the place of the elegant sailing canoes of the past, which have almost completely disappeared. They sometimes carry suicidal numbers of passengers, often travel enormous distances across open ocean, and never take a single life jacket. Many simply disappear, the occupants lost to drowning or sharks.

3. ‘No More ’Um Kaiser, God Save ’Um King’ (#ulink_52a29f05-1bca-5c4a-bb3a-86fa83ca8cff)

Australian Military Proclamation 1914

East of Java and West of Tahiti a bird of dazzling plumage stalks the Pacific over the Cape York Peninsula of Australia, her head almost touching the equator, tail looping above. In her wake she spills clusters of emeralds on the surface of the sea. These are the unknown paradise islands of the Coral, Solomon and Bismarck Seas, the islands lying off the east coast of Papua New Guinea.

As a child I had been captivated by the monolithic Moai statues of Easter Island. Painstakingly, I built a balsa replica of the Kon-Tiki raft on which Thor Heyerdahl tested his theories of the migration of the Incas and their sun-kings across the Pacific to Polynesia two thousand years ago. As I carved, lashed and rigged my diminutive vessel, I dreamed the boyhood dreams of distant voyages to the South Seas with only a green parrot for company. My seafaring uncle, Major Theodore Svensen,

(#ulink_3f20cfbf-4b5d-5096-b1a8-e16942e71c79) a former naval draughtsman born in Heyerdahl’s own Norwegian coastal town of Larvik, was a veteran of the Boer War and the Gallipoli Campaign in 1915. He stoked my imagination with tales of the sea and foreign campaigns, his budgie chirruping on his shoulder, a large tropical butterfly tugging against the thread that tethered it to a palm trunk in his garden.

‘Useless to read books m’boy! Head for the front line! Go to the islands – that’s the last virgin land. Sail before it’s too late!’ he would thunder as he waxed his magnificent moustache, jabbing with a finger at yellowing maps. Many years were to pass before I could attempt such a voyage to Melanesia, and in many ways it turned out to be sadly too late.

The geographical term ‘Melanesia’ originates from the Greek melas meaning ‘black’ and nesos meaning ‘island’. The region was known up to the late nineteenth century as the ‘Black Islands’, a reference to the strikingly dark skin colour of the indigenous population and their former formidable reputation for cannibalism and savagery. Melanesia is situated in the South-West Pacific, south of Micronesia and west of Polynesia, occupying an area about the size of Europe and containing mainland Papua New Guinea, the Bismarck Archipelago, the Solomon Islands, Vanuatu, New Caledonia, Fiji and the innumerable intervening islands. The extreme cultural diversity of the region evades neat categorisation and facile generalisations remain suspect. It can be observed, however, that Melanesian society is more egalitarian and the qualities of leadership more achievement-oriented than in Polynesia and Micronesia, where power is largely based on inheritance.

Melanesian marsupials have been more deeply studied than the origins of ‘Melanesian Man’. The Australian Aborigines and the Negrito populations of South-East Asia are distant relatives from the Pleistocene era some 50,000 years ago. There were two main migratory waves, the ancient Papuan (from the Malay papuwah meaning ‘frizzy-haired’) extending over many thousands of years, and the more recent Austronesian.

(#ulink_53ffb81d-6b68-56ba-ab0f-40b02bc9090f) The intervening millennia have witnessed enormous cultural intermixing. These movements have given rise to the two main cultural traditions in evidence in Melanesia today, the Papuans being the most numerous.

Geographically, New Guinea provided some of the greatest natural obstacles to exploration encountered in any country, with little prospect of gold or cargoes of spices as reward for the sacrifices of the voyage. Nature runs riot in the hot, humid and wet climate. Superlatives abound – over 700 species of birds, 800 distinct languages, the largest butterflies and beetles in the world, five times the species of fish in the Caribbean. Thomas Carlyle idly observed, ‘History, distillation of rumour.’ He could scarcely have known how appropriate his comment would be regarding expeditions to this fabled land.

The earliest surviving sketches of Pacific peoples were four rather crude drawings of warriors observed off the southern shores of New Guinea made in 1606 by the Spaniard Diego Prado de Touar. My destination, the coast and islands of what was to become German New Guinea, were mapped almost lethargically by a procession of European voyages of discovery. The Spanish and Portuguese were followed by the Dutch, who were succeeded by the English and the French. In 1700, that colourful buccaneer-explorer William Dampier aboard HMS Roebuck (a true exotic who mentions in his journal consuming ‘a dish of flamingoes tongues fit for a prince’s table’) found a strait between New Britain and New Guinea. He navigated the coasts of New Ireland and named the larger island Nova Britannia. He was the first European to be recorded as discovering and anchoring in the Bismarck Archipelago, formerly regarded as an integral part of New Guinea.

The French, too, have a distinguished history of New Guinea exploration. In 1768 the French Comte de Bougainville charted New Ireland, the Admiralty Islands, Buka and Bougainville. Louis XVI was an enthusiast for exploration and helped to plan and support the ill-fated expedition of Jean-François Galaup, Comte de Lapérouse. Although an aristocrat, the Comte had remained a darling of the revolution as he had married beneath him for love. For the time, this enlightened navigator held radical views on exploration. He observed in his journal:

What right have Europeans to lands their inhabitants have worked with the sweat of their brows and which for centuries have been the burial place of their ancestors? The real task of explorers was to complete the survey of the globe, not add to the possessions of their own rulers.

He disappeared in the Pacific after leaving Botany Bay in 1788. Louis despatched a search party under the command of Antoine Joseph Bruny d’Entrecasteaux. Part of this voyage of the Recherche and the Espérance in 1792 contributed to the accurate mapping of the Solomon Sea and the Trobriand Islands. This expedition remained the last significant exploration of the Bismarck Archipelago.

Captain John Moresby in HMS Basilisk discovered Port Moresby harbour in April 1873 naming it after his father, Sir Fairfax Moresby, Admiral of the Fleet. In a theatrical gesture he gave ‘some little éclat to the ceremony’ by using a capped coconut palm as a flagstaff to raise the Union Jack and claim possession. Lieutenant Francis Hayter wrote a rare account of this ceremony.

On John emerging from the Bush which he did in a way creditable to any Provincial Stage, we presented arms and the Bugler (who we had to conceal behind a bush as he was one of the digging party and all covered with mud) sounded the salute … spoiled by the Marines who, I believe, fired at the wrong time on purpose, because they didn’t like being put on the left of the line.

Moments of high comedy never failed to pepper this procession of explorations. On one occasion a Lieutenant Yule escaped murder by dancing along the beach nearly naked, dressed only in his shirt. The warriors were so convulsed with laughter at the sight, he managed to reach the safety of the ship’s boat.

The stimulus to explore remained strong among adventurers and geographers, naturalists and ethnologists, not neglecting the joyful and sometimes misguided missionaries who attempted to wrest the islands from the clutches of the Devil. Malaria, earthquakes and cannibalism took a fearful toll of their lives. In the north-west of the country, twenty-five years of evangelism had resulted in more missionary deaths than villagers baptised. The profiteers of the East India Company found little to attract their purses. Their settlement at Restoration Bay in 1793 was soon abandoned. The fabulous plumage of the birds of paradise, pearls and pearl shell, bêche-de-mer and sandalwood became the most important items of trade wherever a European settlement became successful. The British, the Dutch, the French and the Germans, a thousand Hungarians and even a Russian, perhaps the greatest scientific adventurer of them all, Nikolai Miklouho-Maclay, attempted settlements with varying degrees of success.

Colonial flags rose over New Guinea like a flock of doves. The British Imperial Government proclaimed their Protectorate on 6 November 1884 by raising the Union Jack on HMS Nelson, one of five men-of-war present in the harbour at Port Moresby. The local people squatting on the deck heard in Motu the ambiguous words that were to cause much future suffering and discontent – ‘your lands will be secured to you’. German New Guinea had been annexed three days earlier on the island of Matupit in Neu Pommern (New Britain). On 4 November, Kapitan Schering, Kommandant of the Korvette Elizabeth, took possession of the Bismarck Archipelago by raising the German flag on the island of Mioko in Neu Lauenburg (the Duke of York Islands). Another fluttered in the fetid heat of Finschhafen on 12 November, claiming the north-east mainland of New Guinea (Kaiser Wilhelmsland).

Many eccentric and extraordinary individuals were attracted, and still are, to this destination of the imagination. The formidably inhospitable terrain was explored by a bizarre collection of colonial adventurers, a veritable New Guinean comédie humaine. Some exploits were not believed when first reported, but most turned out to be true despite their outrageous detail.

The melodramatic Italian explorer Count Luigi Maria D’Albertis was obsessed with the power of explosives, an authentic pyromaniac, and used every opportunity to set off landmines, petrol, fireworks, rockets with or without dynamite attachments, even Bengal lights which emitted a vivid blue radiance – all to intimidate the warriors in the most flamboyant style. Accordingly, on a May morning in 1876, this theatrical explorer assembled his crew – two Englishmen, two West Indian negroes, a Fijian named Bob, a Chinese cook, a Filipino, a resident of the Sandwich Islands, a New Caledonian, a head-hunter boasting thirty-five prizes to date, and his son acting as a navigator. To defend themselves and pacify the local people, they loaded nine shotguns, one rifle, four six-chambered revolvers, 2000 small shot cartridges and other ammunition, the usual dynamite, rockets and fireworks, a live sheep, a setter named Dash (later taken by a crocodile) and a seven-foot python to discourage pilfering from the luggage.

This extraordinary group entered the estuary of the Fly River in the Gulf of Papua on the south coast aboard the diminutive steam launch Neva, to sail into the interior of New Guinea for the first time. In order to divert himself from the difficulties he encountered, D’Albertis captured specimens of Paradisaea raggiana (Count Raggi’s Bird of Paradise) and examined phosphorescent centipedes. When under attack from villagers, he forced them into terrified submission by igniting cascades of fireworks and rockets. With enviable detachment he wrote in his book New Guinea: What I Did and What I Saw that he admired the beautiful reflections on the water the explosions made between the banks of dark forest. After some 580 miles from the mouth of the river he was forced to turn back, his legs paralysed by the onset of a mysterious illness. Nine war canoes of warriors blocked his path near Kiwai Island. He charged through them with the engine at full steam throttle, Bengal lights ascending into the sky, funnel pouring black smoke whilst he bellowed out an aria from Don Giovanni. He died in Rome of mouth cancer in 1901 after amusing himself in a hunting lodge of Papuan design built on stilts in the Pontine Marshes.

German traders had begun to move into the Pacific during the race for colonies and the first trading stations were set up in Apia in Samoa in 1856. The history of exploration in the Bismarck Archipelago, my destination, is less well known. By the 1870s, business was being done in ‘savage’ New Britain. The German hegemony over the Bismarck Archipelago and Kaiser Wilhelmsland lasted from 1884 to the outbreak of the Great War in 1914. This was a classically ill-fated German colonial adventure, first under the disastrous and punitive Neu Guinea Compagnie and later ruled by the Imperial Government itself despite the fact that Prince Otto von Bismarck was not an enthusiast of colonial adventures.

German New Guinea also attracted its share of fearless explorers. The Austrian Wilhelm Dammköhler spent thirty years travelling through German, Dutch and British New Guinea. He worked on pearling luggers, prospected for gold, and explored the mainland. He was a man with a literary bent as well as a person of some sartorial distinction. In 1898 he had a close shave with a Tugeri head-hunting party. The ferocious Tugeri were among the most feared of all the tribes. They took heads to provide their children with names. They would cover themselves with chalk, set out in their canoes to attack a village and then after grabbing a victim would demand or cajole his name from him. They would then remove the screaming head with a bamboo beheading knife, memorise the name and bequeath it to their newly born.

On this occasion Wilhelm was collecting fresh water, having anchored his cutter, the Eden, at the mouth of the Morehead river. As he rowed upstream he carried, in addition to the water containers in the dinghy, a copy of Byron’s poetry, two silk shirts, a pair of Russian calf boots and a pair of white duck trousers. After some thirty miles he encountered the Tugeri. They calmed themselves when they mistook him for a missionary. Dammköhler played along with the deception:

On the following morning, the chief signed to me to read prayers, whereupon I opened my Byron and read some stanzas out of that … I remained with these friendly natives a fortnight, mixing freely with them, hunting with them etc.; and I kept up my missionary character all the time, reading to them out of my Byron morning and evening during my stay.

How Lord Byron would have loved such an incident. Poor Wilhelm finally bled to death after being attacked on a tributary of the Watut river near the present city of Lae. He was skewered like Saint Sebastian with a dozen fiendishly-barbed arrows in the arms, legs and chest. One severed an artery.

For those romantics and eccentrics, missionaries and mercenaries, desperate speculators, searchers after extremes, explorers, adventurers, swindlers, prospectors and a thousand other misfits who fled from so-called ‘civilisation’, the Black Islands had become a source of mystical and fictional descriptions, ultimately a magnet. New Guinea has always offered the possibility of self-transformation to depressed though imaginative underachievers and individualists. Outsiders unable to accept the prosaic nature of life in the bourgeois society of Europe have always been seduced by New Guinea and its promise of unspeakable adventures.

In the circulating libraries of the time, the public could read of a phantasmagorical world of fabulous creatures like Captain Lawson’s deer, endowed with long manes of silken hair, birds that sounded like locomotives, striped cats larger than the Indian tiger, mountains thousands of feet taller than Mount Everest. They read of men with vestigial tails who sat in their huts allowing the tails to protrude through special holes cut in the floor. There were reports of native cavalry that rode striped ponies and women who ate their children as a form of birth control. They read of the web-footed Agaiambu people, who lived in the marshes and swam through the reed beds, had flaring nostrils like a horse, small legs and buttocks, strange muscular protuberances on their scaly inner calves, walked with the ‘hoppity gait’ of a cockatoo on flaccid, straggling toes and whose feet bled when they walked on dry land. They kept pet crocodiles tethered with vines and raised pigs in slings. New Guinea was a domain of impenetrable tropical jungle and gothic phantasms that might well have been imagined by the French naive painter Le Douanier Rousseau on a particularly creative day.

The islands also attracted visitors of genius who had serious academic intentions. Perhaps the most famous of these was the Polish anthropologist Bronisław Malinowski who, at the outbreak of the Great War, pioneered new methods of fieldwork in the Trobriand Islands. Melanesia subsequently became a cultural laboratory for European anthropologists and one of the most closely studied of the ‘unknown regions’ on earth.

In 1906 Australia took responsibility for British New Guinea and the British Protectorate ceased to exist. The new territory was now to be called Papua. The first Lieutenant-Governor of Papua, Sir Hubert Murray, was an empire builder of Olympian accomplishments. He was a character who seemed to have stepped straight out of Boy’s Own fiction. Born in Sydney in 1861, he stood six foot three, weighed fourteen stone and was amateur heavyweight boxing champion of Great Britain. A rowing blue at Magdalen College, Oxford, and possibly the finest swordsman in Australia, he had read Classics and achieved a double first.

A career as an Australian barrister beckoned but he abandoned the idea as ‘too tedious’. In 1904 the post of Chief Judiciary Officer became available in New Guinea. In need of diversion, he replied to a newspaper advertisement and was offered the post. He adopted a paternalistic style of governorship, promising the Papuans, ‘I will not leave you. I will die in Papua.’ At the time he was considered progressive but now is considered by indigenous historians as being regrettably colonial. He greatly admired men who exercised self-discipline and refused to open fire on the most threatening of warriors. While travelling the country on his circuit he carried a portable library. His nephew recalls seeing him reading a Greek text in rough weather, seated in a chair lashed to the deck of his small government vessel Laurabada, holding it above the waist-high foam to keep it dry.

He wrote a number of excellent books recalling his tours of duty, full of wry observation. He mounted expeditions into the interior and developed a degree of understanding of native customs and languages unusual in colonial administrators of the time. His laconic style keeps one turning the pages. He describes murder in his book Papua or British New Guinea published in 1912:

… murder to these outside tribes is not a crime at all; it is sometimes a duty, sometimes a necessary part of social etiquette, sometimes a relaxation, and always a passion. There is always a pig mixed up in it somewhere … Cherchez le porc.

He later refers to the reputation of ‘… the Rossel islanders who were quite oblivious to the most ordinary rules of hospitality’ and ate 326 Chinese who had been shipwrecked on the island. He informs us that in some villages ‘a thief is punished by killing the woman who cooks his food’ as this causes great inconvenience to the thief.