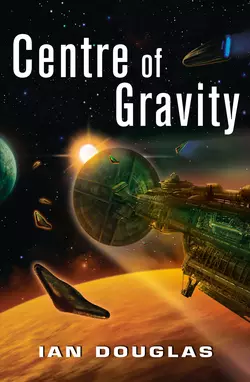

Centre of Gravity

Ian Douglas

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 612.81 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: The second book in the epic saga of humankind′s war of transcendenceIn the evolution of every sentient race, there is a turning point when the species achieves transcendence through technology.The warlike Sh’daar are determined that this monumental milestone will never be achieved by the creatures known as human.On the far side of known human space, the Marines are under siege, battling the relentless servant races of the Sh′daar aggressor. With a task force stripped to the bone and the Terran Confederation of States racked by dissent, rogue Admiral Alexander Koenig must make the momentous decision that will seal his fate and the fate of humankind.A strong defensive posture is futile, so Koenig will seize the initiative and turn the gargantuan Star Carrier America toward the unknown. For the element of surprise is the only hope of stalling the Sh′daar assault on Earth′s solar system—and the war for humankind′s survival must be taken directly to the enemy.