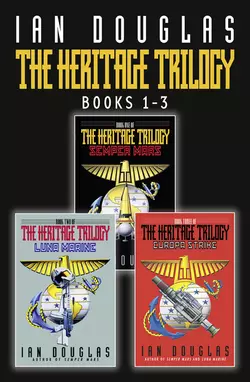

The Complete Heritage Trilogy: Semper Mars, Luna Marine, Europa Strike

Ian Douglas

The Marines have landed on Mars to guard the unearthed secrets of an ancient and dangerous alien race: Ourselves…This bundle includes the complete Heritage Trilogy by New York Times bestselling author Ian Douglas.The Year is 2040.Scientists have discovered something astonishing in the subterranean ruins of a sprawling Martian city: startling evidence of an alternative history that threatens to split humanity into opposing factions and plunge the Earth into chaos and war. The USMC – a branch of a military considered, until just recently, to be obsolete – has dispatched the Marine Mars Expeditionary Force, a thirty-man weapons platoon, to the Red Planet to protect American civilians and interest with lethal force if necessary.Because great powers are willing to devastate a world in order to keep an ancient secret buried. Because something that was hidden in the Martian dust for half a million years has just been unearthed . . . something that calls into question every belief that forms the delicate foundation of civilization . . .Something inexplicably human.This bundle contains Semper Mars, Luna Marine and Europa Strike - the complete Heritage trilogy.

Ian Douglas

The Heritage Trilogy Books 1–3

Contents

Cover (#u4d42f92a-fee4-567e-a64e-21f782726187)

Title Page (#u14adee15-f33e-594a-ae80-70aae8f8268a)

Semper Mars (#uf71daf60-e309-5966-abd1-3a4d533234bb)

Luna Marine (#litres_trial_promo)

Europa Strike (#litres_trial_promo)

By Ian Douglas (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

SEMPER MARS

BOOK ONE OF THE HERITAGE TRILOGY

IAN DOUGLAS

Contents

Map

Prologue

“Christ, CJ! You can’t let them do this to us!”

One

This wasn’t the first time the Marines had ventured into…

Two

“How’s it working now?” Garroway asked, slipping into the seat…

Three

Kaitlin Garroway took the second-floor door out of Herb Simon…

Four

Sergeant Gary Bledsoe, USMC, stood at his sandbag-encircled post on…

Five

“Snakebite, this is Basket. Excalibur. I say again, Excalibur.”

Six

“All right, people!” Colonel Lloyd bellowed. “Listen up! We got…

Seven

Kaitlin Garroway peered out the cabin window at a sky…

Eight

“I never thought I’d see the day,” Garroway said, “when…

Nine

The last pale glow of the sunset had long since…

Ten

It was just past midnight, the time of the day…

Eleven

Most of the Marines in the barracks area were asleep.

Twelve

“I talked to Doc Casey,” Garroway told the others at…

Thirteen

“So, you got your lines down?” Garroway asked. It was…

Fourteen

It had been eight days since Kaitlin had seen Yukio,…

Fifteen

According to the data displayed on the seatback screen, the…

Sixteen

It was, Garroway thought, one of the oddest-looking marches in…

Seventeen

Mark Garroway watched his daughter’s face on the Mars cat’s…

Eighteen

The president looked a lot older now than he had…

Nineteen

The Star Eagle Michael E. Thornton, a single-stage-to-orbit SCRAMjet transport,…

Twenty

“So,” Mark Garroway said in what he’d intended to be…

Twenty-One

“Cheyenne Mountain, Shepard,” Colonel Dahlgren said, peering into the telescopic…

Twenty-Two

They’d broken out of the narrow canyon that stretched across…

Twenty-Three

Thirty hours after the MMEF’s triumphant return to Mars Prime,…

Twenty-Four

“Down!” Caswell cried, throwing herself facedown into the sand. “We’re…

Twenty-Five

Kaitlin was on the floor in the den playing chess…

Epilogue

Marine Lieutenant Kaitlin Garroway walked through the automatic doors of…

Map

2039

PROLOGUE

MONDAY, 6 JUNE

Office of the Chairman of the

Joint Chiefs of Staff (CJCS)

The Pentagon, Washington, DC

0950 hours EDT

“Christ, CJ! You can’t let them do this to us!”

General Montgomery Warhurst teetered between radically opposing strategies, storming and pleading. The five-star admiral seated behind the broad and brightly polished oak desk before him was not only his commanding officer, but his friend. He and Admiral Charles Jordan Gray went way back. They’d been middies together at the Naval Academy, Warhurst in the Class of ’08, Gray in the Class of ’07. Since their postings to the five-sided squirrel cage, they’d attended one another’s social affairs, had barbecues in each other’s backyards, and shared the same wry disdain for Beltway politics. For them, the old Marine-Navy rivalry was a seal on their friendship, banter and laughing bluster over a couple of beers.

But, by God, Warhurst wasn’t going to let them kill the Corps, wasn’t going to let C. J. Gray kill the Corps, not if he had one thin, ragged breath.

Gray gave him a sad smile. “What’s the matter, Monty? Trying to save your job?”

“That’s not funny. I may be commandant of the United States Marine Corps, but every Marine is a rifleman first. I’d resign in an instant if it would change this. You know that. I’d give my life for the Corps, CJ. I goddamn would.”

The smile vanished. “Jesus, Monty, I know how you feel, but—”

“Do you?” Warhurst gestured at the four-meter flatscreen dominating the wall behind Gray’s desk. The display repeated in hand-high letters the document called up by the admiral’s wrist-top. The words “HR378637: The Unified Military Act” showed at the top of the neatly formatted document in punch-to-the-stomach bold. “The BBs’ve been whittling away at us for years now, cutting our appropriations until we’re damn near running on empty. Now it’s…this.”

Warhurst stopped himself. He was breathing hard, and he could feel the rising flush in his face, feel the blood hammering at his temples. His meds monitor would be kicking in any second now if he kept this up, but, damn it, the BBs—Pentagon slang for “Beltway Bastards”—never failed to raise his blood pressure.

And now they were trying to kill the Corps. His Corps!…

“There’s not a damned thing I can do about it,” the admiral said, shaking his head. His gaze flicked to the left, to the large, 3-D image of a grinning civilian on the wall to his right. “Archy’s backing this thing, and that means it’ll have the president’s approval.”

“Severin is a political hack. He’s also an Internationalist—”

“May I remind you that Archibald Severin is secretary of defense, which makes him our political hack. That means you, me, and the rest of the Joint Chiefs answer to him…and after him the NSC and the president. They pass the word, and we snap to attention, say ‘Yes, sir,’ and politics never rears its ugly face.”

“Everything in Washington is politics, CJ, and that includes the Pentagon and everyone in it. You know that as well as I do.”

“Maybe. But the final word comes from a document you may have heard of: the Constitution, remember? It says we work for the politicians. Not the other way around.”

“I never suggested any different. But this Unified Military Act is political. You know it. I know it. And there’s a political way to fight back.”

“And what might that be?”

“Public opinion.”

The admiral groaned, shifting in his chair. “Jesus, Monty—”

“It’s worked before. Truman? A century ago?” President Harry S Truman, a former artillery officer in the Navy, had come that close to shutting down the Marine Corps in the years immediately after World War II, declaring it to be unnecessary. Public opinion, however—the opinion of Americans who remembered names like Wake, Tarawa, and Iwo Jima—had secured a place for the Corps, by law, in the National Security Act of 1947. And that wasn’t the first time Washington politicians had tried to kill or dismember the Corps. Congress alone had tried it on no fewer than five separate occasions between 1829 and the 1940s.

And each time, public opinion, in one way or another, had played a part in rescuing the Corps from the budget cutters’ hatchets.

“I know that look,” the admiral said. “You’ve got something in mind, or you wouldn’t be in here waving your arms at me.”

Warhurst bent over, picked up the briefcase he’d set on the thick-carpeted floor when he’d entered the CJCS’s office ten minutes before, and set it on Gray’s desk. Touching the lock points, he opened it wide and extracted his PAD, which he slid across the desk, screen up.

Gray picked the thin panel up, his touch awakening the screen. He frowned as he read the document displayed there.

“Mars? You want the Marines to go to…Mars?”

“To safeguard American interests there, CJ. The same way the Marines have safeguarded American interests all over this world.”

Gray touched the turn-page corner of the PAD. “How big an operation is this?”

“The logistics are laid out on page five,” Warhurst said. “I’m suggesting one platoon, twenty-three men. Plus an HQ element. Thirty men in all.”

The admiral paged through several more screens. “Very complete.” He looked up at Warhurst, one white eyebrow askance. “And it’s certainly topical. But you can’t be serious.”

Warhurst reached across the desk and tapped a touch-point on the Personal Access Device. There was a moment while the PAD searched for the office’s network channels, and then the flatscreen behind the admiral’s desk flashed to a new set of uploading images. Gray swiveled in his chair to watch the display, which tinted the room with its ruddy glow.

Red sand and ocher stones littered an uneven, rolling ground as far as the eye could see, beneath a sky gone eerily pink and wan. An American flag hung from a mast in front of a cluster of pressurized domehuts, a tiny symbol of national defiance stirring listlessly in the thin wind. On the horizon, miles away but looming large enough to seem much closer, was the mountain. It reminded Warhurst sharply of Ayers Rock in the Australian outback, monolithic, vast, and red in the distance-chilled sunlight. The surface was sand-polished and smooth, its original angles, planes, and swellings worn down by the wind erosion of five hundred millennia, but the features were still discernible.

Or so some said. There were still voices—and powerful ones, at that—insisting that the so-called Cydonian Face, the Face on Mars, was a natural feature, a kind of cosmic prank elicited by shadows, coincidence, and the irrepressible human will to believe.

This despite the latest reports from Cydonia Base.

“In five more months,” Warhurst said, “Columbus will cycle past Mars and deliver her payload. They used a sealed hab payload, as was their right by the International Space Commerce Treaty…but Intelligence tells us the passengers include fifty soldiers of the Second Demibrigade, Legion Étranger—French Foreign Legion—in the service of the United Nations. That’s more soldiers than we have scientists on Mars, right now…and they’ll be armed, where our people are not.”

Admiral Gray turned away from the flatscreen, scowling. “I needn’t remind you, surely, that the administration is fighting for its life, right now. And trying like the devil to keep a low profile where the UN is concerned.”

“I’m well aware of our current…foreign policy,” he replied. The way he said it added the words lack of in front of the word foreign.

“And how is sending thirty US Marines to Mars supposed to defuse a situation that is just a step or two short of outright war?”

“Maybe it doesn’t,” Warhurst said. “But maybe the president would like an option that doesn’t have us ducking for cover every time some two-bit dictator in South America or Asia sneezes and blames us. Maybe stationing troops on Mars to safeguard our interests—and we’re still allowed to do that, I remind you, under the charter—maybe that would convince Geneva to back off and cut us some slack.”

Gray tapped several touchpoints on the PAD. The image of America’s xenoarcheological station on the bitterly cold and windswept Cydonian plain remained on the wall flatscreen, but Warhurst’s proposal came up on the PAD display. “Hmm. And, just incidentally, it ingratiates the Marines with the American public, eh?”

“Maybe the American public is tired of getting kicked around by those two-bit dictators, too, CJ.”

“Maybe. And maybe Congress won’t want to shut down the Marine Corps while thirty Marines are on their way to protect our people on Mars.” Suddenly, he grinned, a cold and lopsided showing of teeth. “My God. SECDEF and State are going to shit their pants when they see this.” He paused and shook his head. “Damn it, Monty, why the stick up your ass? Maybe Archy and the rest are right, and it’s time to let the Corps retire, with dignity. With honor. Warfare has changed in the last century, you know…or haven’t you been paying attention? Marine amphib ops like Inchon and Tavrichanka are things of the past. We’ll never see a major amphibious landing again, not when satellites and space stations make secrecy impossible in any deployment. Do you want the Corps to end up as nothing more than the Navy’s police force?”

“There are still a few things us Marines do that the other services don’t,” Warhurst replied. He looked down at the desk top for a long moment. “I’ll tell you, though, CJ. The reason, the real reason, doesn’t have that much fact or experience or science behind it. You know I have a son in the Marines. Ted’s planning on making it his career. And his son, my grandson, Jeff. Eleven years old. He commed me just the other day to tell me he was going to be a Marine. Like his daddy. Like me. What the hell am I supposed to tell him, CJ, if they kill the Corps? The tradition? It would be like killing part of who we are.”

Gray sighed. “There aren’t any easy answers, Monty. You know that. The UN is pushing, pushing hard, to reduce all national militaries to a minimum.”

“I’ll let the politicians worry about disarmament,” Warhurst said. “What I don’t want to see is my son’s face…or Jeffie’s, when I have to tell them that the Marines are being shut down, that their country doesn’t need them anymore.”

“A hell of a note,” Gray said, “proving we need them by sending them to Mars.”

“The Marines,” Warhurst replied, “always go where they’re needed.”

2040

ONE

WEDNESDAY, 9 MAY

Cycler Spacecraft Polyakov,

three days from Mars Transfer

1517 hours GMT (shipboard

time)

This wasn’t the first time the Marines had ventured into space, not by a long shot. On February 20, 1962, Colonel John Glenn, United States Marine Corps, had become the first American in orbit, thundering into space atop a primitive Atlas-D booster. Of course, Navy astronauts were quick to point out that Alan Shepard, a former US Navy aviator and test pilot, had been the first American in space nine months earlier, even if his suborbital flight—with a full five minutes in zero G—had also been the shortest spaceflight in history.

Major Mark Alan Garroway did not think of himself as an astronaut, even though he’d been in space for seven months, was drawing astronaut’s flight pay, and was watching now as Mars drifted past the command center’s main viewport. He was a passenger—in effect, he was extremely expensive cargo—aboard the Polyakov, one of four cycler spacecraft set to shuttling between Earth and Mars in the past decade. He was a Marine, and as far as he was concerned, sharing bridge watches with the ship’s three officers—two Russians and an American—did not make him an astronaut. That distinction was reserved for the glory boys and girls of NASA’s Astronaut Corps and the Russkii Kosmonaht Voiska. Marines liked to boast that every Marine was a riflemen first, and that any other job description—whether that of AV-32 pilot or combat engineer, of electronics and computer specialists like Garroway or the goddamn commandant of the whole goddamned Corps—was at best a minor elaboration.

Garroway was still less than enthusiastic about this mission, even after seven months in space. The routine had swiftly become tedious, especially after the magnificence of the blue and cloud-smeared Earth faded to nothing more than a brilliant, blue-white star. It was the sameness of life aboard ship, day in and day out, that ground away at his nerves, convincing him that this time, finally, once and for all, when the mission was done and he got back home, he was going to retire from the Corps at last. That tour-boat concession in the Bahamas was looking better and better with each passing watch. Kaitlin, his daughter, had been accusing him of going soft, lately, in her frequent v-mails. Well, maybe she was right. It was hard to stay gung ho for twenty-five years in a Corps dying of slow starvation…and with nothing much to show for it but a ticket to Mars and a hell of a long tour away from home.

Mark Garroway was the second-highest-ranking officer in the Marine Mars Expeditionary Force, a thirty-man unit comprised of a single, specially assembled weapons platoon on special deployment…very special deployment. General Warhurst himself had put this op together, a last-ditch attempt at saving the US Marines from the Washington compromiser corps. Tradition might dictate that Garroway was a rifleman first, but he rarely thought of himself as such these days. He was forty-four years old and had been in the Corps for almost twenty-five years. A mustang, he’d started out as an enlisted man, an aviation electronics specialist. When he’d re-upped after his first hitch, however, the Marines had paid for him to finish his interrupted tour at college, including stints first at MIT, and later at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh, and his area of expertise shifted from straight avionics to the obtuse, complex, and frequently highly classified electronics found in military communications, robotics, and AI computer systems. By then, of course, he’d received his commission, and he spent most of the next ten years working on classified programs at half a dozen research labs, from Aberdeen, Maryland, to Sandia, New Mexico, to Osaka, Japan.

His communications electronics expertise was the reason he was a part of the MMEF. Technically, he’d volunteered as a CE Tech for the Marine Mars Expeditionary Force, but no less a Corps luminary than General Montgomery Warhurst had personally requested that he accompany the expedition, and so far as Garroway was concerned, a request by the commandant of the US Marine Corps was a direct order—a politely disguised one, perhaps, but a direct order all the same.

Garroway’s primary responsibility on the mission was to oversee the maintenance of the Marines’ computers and electronic gear—especially the microcomp circuits that controlled their battle armor, commo gear, and assault rifles. Vital work, certainly, but considerably less than a full-time job. If it hadn’t been for the fact that he was also Colonel Lloyd’s executive officer, his second-in-command, Garroway thought he would have gone mad from the boredom by now.

His eyes followed the stately drift of Mars past the control deck’s windows. He still hadn’t accustomed himself to the strangeness, the alienness of the world. At the moment, it looked like a small and seriously diseased orange, its overall yellow-ocher coloration interrupted by patches, streaks, and smears of dark browns and grays. The north polar ice cap was a slender glimmer of sun-dazzled white. That band of black and dark red along the equator was almost certainly the Valles Marineris…the Valley of the Mariner Spacecraft. Despite over a year of study, he could recognize little else in the way of surface features save the polar cap and the three dark smudges of the Tharsis volcanoes.

And then the Polyakov’s slow rotation carried the planet past the edge of the window, and he was looking at stars and emptiness once more.

To his left, Commander Joshua Reiner reached up and tapped one of the monitor displays on the console above his workstation in that annoying way people have of trying to chivvy delicate electronics into proper operation. “Hey, Garroway?”

“Yeah?”

“We got a fault in camera sixty-two. No picture.” Reiner tried upping the gain on a volume control. “No sound, either.”

“Is the thing on?”

“Yup. Readouts say it is, anyway. Must be a loose connection.”

Garroway snorted. Trouble with electronic systems was always dismissed as “a loose connection,” even when the whole system was solid-state, with no wires to come loose in the first place. Pivoting his seat, he took a look over Josh’s shoulder, verifying that the system was on, but without sound or picture.

“Huh. I see what you mean.” The control-deck console was receiving a visual feed, but the screen was black. The sound, though, appeared to have been switched off.

“Storm cellar,” Reiner said, identifying the location of the dead camera. “It’s done this a few times before. Probably nothing major, but we have to log the failure for maintenance, y’know?”

“I’d let it go,” Garroway replied, leaning back in his seat. He was pretty sure he knew what the problem was “See if it fixes itself.”

“Um. Trouble is, old L&M’s on his way up there.”

“Eh? Why? When?”

“He’s logged for…let’s see.” With a few taps on his keyboard, Reiner called up a schedule on one of his monitors. “Here it is. Platoon weapons assembly drill, RSHF, 1530 hours.”

“Oh, shit,” Garroway said, glancing at the digital time readout on a nearby bulkhead. He’d prepared that schedule last week but forgotten that a drill was on for today.

“Yeah. And you never know if he’s gonna want a vid record of the drill.”

“Yeah, roger that.” He pushed back from his console. “I’d better get up there before he does. Cover for me here?”

“You bet.”

Garroway walked across the control deck, ducked low, and stepped through the open hatch into the transport-pod accessway. He moved carefully; spin gravity at the control-deck level was currently only about two-tenths of a G, and a careless move could send him slamming into the overhead.

“L&M” stood for “Lloyd and Master,” the wry sobriquet of Colonel James Andrew Lloyd, the MMEF’s commanding officer. The name was strictly unofficial, of course, used only behind his back by those who had to work with him. Lloyd was a stickler both for regulations and for proper form. His weapons drills aboard the cycler spacecraft had made him notorious; what, the ship’s astronaut crew frequently asked one another in Garroway’s hearing, could possibly be accomplished by drilling Marines in disassembling and reassembling their weapons in zero G? It wasn’t as if they would need to accomplish the feat on Mars, where one-third gravity kept the inner workings of their M-29s conveniently anchored.

Technically, Lloyd held no more authority aboard the cycler than any of the other Marines—or the civilian scientists, for that matter. The ship’s commanding officer was Polkovnik Natalia Filatinova, and she was the one who set the standards by which the men and women in her charge behaved. Nevertheless, old L&M wouldn’t like it if the storm shelter was used for…unofficial activities.

Garroway touched the transport-pod call key mounted on the bulkhead between two lockways. Several moments dragged past, and then he heard the chunk-hiss of a connection being made, and the sealed airtight door swung ponderously open.

A man clambered out, tall and dark-skinned, mustached, clad in a NASA-blue coverall. Two mission patches adorned his left shoulder: the light blue flag of the United Nations, and the circular sword-on-Mars emblem with the letters OEU:AE.

Organisation des Nations unies: Armée de l’Espace. The United Nations’ Space Force.

“Monsieur Colonel Bergerac,” Garroway said, stepping aside to clear a way for him.

“Hello, Major.” The man’s English was perfect, his eyes cold. “Going down? Or up?”

“Up, monsieur.”

“Ah?” He questioned with eyebrows and a cocking of the head.

“An electronic fault. Nothing serious.” Grateful that the French colonel seemed uninterested in pushing the question further, Garroway ducked through the lockway and into the transport pod beyond. A touch of a keypad sealed the lock behind him, and then, he was climbing up one of Polyakov’s three two-hundred-meter arms.

He didn’t like Bergerac. The man was a cold fish, and he clearly didn’t like Americans, a dislike made sharper by the current state of cold-war standoff between the United States and the United Nations. Intelligence had reported the suspicion that Bergerac and the three officers traveling with him to Mars were carrying sealed orders of some kind for the UN troops already there, and Garroway was inclined to believe it. The man acted as though he was brooding over some dark and enjoyable secret.

He felt a mild giddiness as the transport pod continued rising up the strutwork tower. There were no windows, so he couldn’t gauge his progress visually, but he could feel the spin gravity dwindling away to almost nothing. Polyakov was designed like a three-bladed propeller on a slender shaft. The strutwork blades supported the hab modules, control deck, and labs some two hundred meters out from the central spine, where one revolution in forty-five seconds mimicked the 0.38-G surface gravity of their destination. On the inward leg of the cycle, the ship’s rotation would gradually be increased to two revolutions per minute, working the Earth-bound passengers up to nine-tenth’s of a G by easy steps.

At the hub of the cycler were the supply modules, fuel, air, and water tanks, the docking bays for cycler shuttles, and, at the end of a long boom extending five hundred meters clear from the rest of the ship, Polyakov’s GE pressurized-water 50 MWe fission reactor.

And, because of the sheer mass of its shielding, Polyakov’s storm cellar was also mounted on the spine, just down the hub from the multiple docking collars, core transport-pod accessway, and main airlock. Only rarely was the big module referred to by its official name, the Radiation Shielded Hab Facility, or RSHF. Usually, it was called simply the “storm cellar,” and with good reason…even if the cycler’s out-is-down spin gravity dictated that Polyakov’s crew had to go up to reach it. Solar flares were infrequent hazards of flight, but when a small patch of the sun’s surface suddenly brightened by a factor of five or ten times, spewing high-energy particles out in a deadly cloud, there was no way that a spaceship en route between worlds—locked by fuel requirements and the laws of physics into its slow-arcing orbit—could turn around and return to port…or even take evasive action, for that matter. The storm cellar was the one compartment aboard ship large enough and heavily shielded enough to give the cycler’s crew and passengers a chance of surviving if they were caught by a bad flare.

It was also, by reason of its relatively remote location, one of the very few places on board a cycler where someone could leave the crowded hab modules and find a little precious privacy….

“Storm Cellar”

Cycler Spacecraft Polyakov

1524 hours GMT

Sex in zero G, David Alexander thought, was wonderful…though it could be even more exhausting than its tamer, gravity-leaded incarnation. The novelty of no up or down, no on top or underneath, as the coupling pair twisted in a thin, hovering mist of drifting sweat droplets, brought an exotic newness to this most ancient of recreations.

Carefully, he leaned back a little, so he could focus on the dozing face of his lovely partner, framed in a golden splash of hair adrift in zero gravity, and as he did, he felt—again—that tiny, nagging pang of guilt. Alexander was married, but not to this woman. It had taken a lot of loneliness—and the rather heavy-handed rationalization that his marriage to Liana was all but over anyway—to get him to the point where he’d surrendered to the very considerable temptation. Mireille Joubert was a beautiful woman and an intelligent one; she clung avidly to the European notion of cosmopolitan maturity that saw nothing wrong with two adults enjoying recreational sex, whether either of them was married or not.

Mireille Joubert. Her first name was difficult…and a delight. She’d had to coach him on the pronunciation, which came out something like mere-ray. He turned his gaze to a drifting wad of clothing a few meters away, remembering fondly how frantically the French woman had shucked off her jumpsuit. Two emblems adorned her suit’s sleeve—a blue UN flag, and a round patch displaying the Cydonian Face. He could just make out the words embroidered around the patch’s rim: Expédition Xenoarchéologique de l’Organisation des Nations unies.

He frowned. There were some who would say that their lovemaking was treason. Well, screw that. Mireille Joubert was his colleague, on her way to Mars to assume her new position as director of the UN archeological oversight team there, a small group of men and women assigned by Geneva to monitor US discoveries and excavations at Cydonia.

He didn’t really give a damn about the political situation, and his only interest in the reports of UN troops on Mars—or of the Marines, for that matter—was to marvel at the stupidity of sending soldiers to the red planet instead of more scientists. He, for one, intended to work closely with his UN colleagues, and the hell with international tensions. Technically, the UN team had no real authority on Mars, though their reports and recommendations could bring political pressure to bear back in the United States on the agencies and foundations sponsoring the Mars digs. Aerologist Dr. Jason Graves, already on Mars with the thirty-some US and Russian scientists on the planet, was the head of the Planetary Science Team. Alexander had worked with the man before and doubted that there would be a problem with his liaison with Joubert. She certainly didn’t seem to think there was a problem with their fraternization.

Alexander started to ease his way from the woman’s sleeping embrace, but the movement set them slowly tumbling, and she opened her eyes. “Mmm. You are wanting to do it again?” Her long, naked legs, clasped about his hips, tightened. He’d thought he was sated, but he could feel the stirrings of renewed interest as she moved against him.

“Do we have time?”

“Quelle heure est-il?”

He knew a little French. She had been teaching him. He glanced at the time display on his wrist-top. “Uh…almost fifteen-thirty.” Shipboard time followed military and European usage, with a twenty-four-hour clock.

“Ah, well…I must go over the site plans with LaSalle at sixteen….”

He sighed. “Perhaps we’d best undock, then.” Zero-G sex, for obvious reasons, had picked up a lot of spacecraft maneuvering terminology. “Docking,” “probe insertion,” and “docking-collar contact” were favorites.

She pulled him closer, nuzzling his ear and enveloping his head in a sweet-smelling, drifting blur of golden hair. Her hips moved in interesting ways. “Oh, but we have much time yet….”

He groaned—happily—then surrendered to warmth and growing hunger. He still felt clumsy with Joubert, even after…what was it? Five times. Or six. He wasn’t sure. Their first time in the storm cellar, they’d used a Velcro strap to keep themselves tied together at their waists; any movement in zero G could have unforeseeable action-reaction repercussions, and when both partners were moving enthusiastically it was difficult to stay docked.

Joubert, though, was an expert at this sort of thing. Either she’d done it before, lots, he thought, or she was a damned fast learner. Superbly acrobatic, she used her legs to keep them tightly joined, flexing knees and thighs like an equestrian to give the necessary friction.

The motion started them turning again, a slow tumble through the mist of their lovemaking. Lazily, he reached out with one arm and caught a stowage-bin handle, checking their spin. Space was precious aboard a cycler. Much of the hexagonal chamber’s interior space was taken up by supply bins anchored by bungee cord and Velcro to the room’s inner surfaces. Fifty or sixty people could have squeezed into the shelter at once if necessary—hab compartments in microgravity acquire a third dimension that makes them far roomier than the same volume of space on Earth—but it would have been a ghastly exercise in claustrophobic conditioning. There were no windows, of course. Ports would have compromised the shelter’s armor. He’d often wished that he could look out into space during one of these sessions….

A metallic thump sounded somewhere close by.

Alexander reared back from Joubert, startled, his heart pounding harder now. The cycler was always noisy, especially here at the hub, where the rotors that kept the hab modules turning provided a constant background hum, and the effects of uneven solar heating on the stationary spine made a sound like far-off thunder. The sounds were muffled, though. Air pressure aboard the cycler was kept deliberately low, which meant that sounds didn’t carry well. This had been close…and very loud.

There was only one thing it could have been—a transport pod docking with the hub spin-connector module.

Shit!…

“Mireille, someone’s coming!” he hissed, disentangling himself. “Quickly! Get dressed!”

Too late. The storm cellar’s hatch leading to the connector mod was already swinging inward. Alexander recognized the lanky, backlit form of Major Garroway crouched in the opening, holding the hatch open but keeping his head primly turned away.

“If there’s anyone in here pulling inventory,” Garroway called loudly, “they’ve got about two minutes before Colonel Lloyd, Lieutenant King, and twenty-six Marines come barging in for weapons drill!”

“Right!” Alexander yelled back. “Almost done!”

Garroway pulled the hatch closed with a muffled clank, and the two of them were alone again…at least for a couple more minutes. They began grabbing for floating items of clothing. His T-shirt was carefully wrapped around the lens of camera sixty-two, mounted on a corner of the bulkhead. He decided to leave it in place until they both were more fully dressed.

With a rattling snort, he forced a sharp intake of air past blocked nasal passages. “What do you think?” he asked the woman. “Is the smell in here too bad?”

Polyakov was the newest of the fleet of four Earth—Mars cyclers, assembled in 2037, but she’d still acquired a zoo of ripe aromas from the tiny, claustrophobic communities that had accompanied her on two circuits from Earth to Mars and back. Fortunately, seven months of living aboard had dulled Alexander to the stench enough that he scarcely noticed anything now…and when he’d entered the microgravity hub of the assembly, nasal congestion settled in and pretty much killed whatever olfactory senses he might have had left.

Despite that, he could detect the heavy muskiness hanging in the hot air, mingled odors of sweat and passion.

“Ohh, David,” the woman said with coy amusement. “How romantic….”

“We don’t want them to know, do we?”

Joubert gave a delicate shrug, then folded her knees to her bare breasts and slipped both legs at once into her red panties. “And if they know,” she said, “it is that they will simply be jealous, yes?”

“I’d kind of like to avoid that if we can,” he said, reaching for white briefs adrift in the air.

She smiled, playful. “Ah. You are afraid your wife finds out?”

“It’s not that.” Well, not entirely. At the moment, he was more afraid of the teasing he was likely to get from the other Americans aboard Polyakov. Four Team scientists, plus thirty US Marines, and the one Navy guy, Reiner, who was with the ship’s regular crew. That was a hell of an audience.

The compartment tumbled lazily about his head. He had his underpants on at last, but he was having trouble imitating the woman’s casual flexibility with the coveralls, and he kept getting both feet tangled in the same leg hole. Damn it all. You’d think that after seven months he’d have managed to learn how to dress himself….

Well, to be fair, he’d not had to dress in microgravity except for the few times he’d come up here with Joubert, one of the distinct advantages of having spin-gravity hab modules. How was it that she could be so graceful with no more practice than he’d had? Already dressed, she anchored herself from a handhold on the bulkhead, then grabbed his shoulder to brace him as he finally slid into the garment and zipped it up. Moving to the bulkhead, he untangled his T-shirt from the camera lens and switched the unit’s sound back on. Swiftly, then, he used the T-shirt as a towel, trying to soak up some of the swirling mist of various bodily excretions in the air.

A second clang sounded from the next compartment. A moment later, the hatchway banged open and a file of Marines in Class-Three armor began crowding boisterously through into the long, hexagonal chamber.

“Fall in! Fall in!” one Marine was shouting. He wore a gunnery sergeant’s chevrons on his sleeve.

“Whee-oo!” another shouted as he squeezed through the hatch. “I do believe I smell fresh puss—”

“As you were, Donatelli!” the gunny sergeant, catching sight of Joubert and Alexander before the others did. “There’s a lady present!”

“Surely ya don’t mean me, Gunny,” a hard-muscled woman Marine growled as she pushed into the compartment.

“He said ‘lady,’ Caswell. Not hormone-junky.”

“Screw you, Marchewka.”

“Silence! Fall in at attention!”

The crowd fell uncomfortably silent after that, each Marine grabbing on to a handhold to anchor himself more or less in line with the others. Alexander eyed them with distaste…ten or fifteen men and women who were suddenly making the storm cellar as confining as the inside of a walk-in safe. They carried rifles and wore partial armor—breastplates and open helmets, worn over dark green BDUs. The breastplate shells were made of an artificial laminate that took on the color of its surroundings, but that hadn’t stopped most of the Marines from customizing the things with some artistic touches of their own. Mange la merde was scrawled in red on one Marine’s armor. Dirty UNdies read another. Alexander scowled. No wonder America’s relations were so bad with the rest of the world, if these were her ambassadors.

Alexander decided that he and Joubert had better clear out before the way was completely blocked. He took a last, surreptitious look around to make sure there wasn’t any clothing adrift, then started moving toward the hatch. Joubert followed.

“Gangway, people!” the sergeant snapped. “At ease and make a hole! Civilians comin’ through!” The line of Marines hauled themselves back out of the way, giving the two of them just enough room to squeeze past. Released from attention, several Marines whispered among themselves, and someone giggled.

“Uh…excuse me,” one called out, “but did one of you lose something?”

Alexander paused at the hatch, turning in time to see a lacy, bright red bra drifting past the faces of grinning men and women. Joubert, with far more aplomb than Alexander was feeling at the moment, snagged the garment, and darted ahead through the hatch. Alexander followed, clumsily, as laughter exploded behind him.

In the connector module outside, Alexander came face-to-face with Major Garroway, who was clinging to a bulkhead beside the transport-pod hatch. The module, which was locked to the rotating hub collar, was turning slowly with a heavy, grinding sound, though here at the very center of rotation, the spin gravity at the walls was still practically nonexistent. According to the lights on the control panel, a second pod was on the way, carrying, no doubt, the rest of the MMEF section. The pods, which worked in tandem like Swiss Alpine elevated cars to preserve the cycler’s spin, could carry only about fifteen people at a time. The second car would be here any moment, and then things would really get crowded.

With a loud clunk and the hiss of matching pressures, the second pod arrived, and the hatch opened up. Another line of lightly armored men and women spilled out, moving rapidly across the module toward the storm-cellar hatch. Last out was a tall, ebony-skinned Marine in fatigues, wearing the silver eagles of a full colonel at his collar. “What are you doing here?” he demanded, glaring at the two civilians.

“Uh…inventory, Colonel Lloyd,” Alexander replied. “Just…uh…checking the stuff the arky teams’ll need at Cydonia.”

Lloyd gave them a single brief, penetrating, and disdainful look, then followed the rest of his men into the cellar.

Alexander let the major and Joubert clamber into the waiting pod ahead of him. From the still-open door of the storm cellar, he heard Lloyd’s familiar bellow. “All right, people. Enough skylarking!”

The cellar door boomed shut, cutting off the voice. Alexander clambered through the pod hatch and grabbed a handhold next to the major.

“Thanks,” Alexander told him. “For the warning, I mean.”

“Yeah.” Garroway’s voice was hard and cold. His eyes were on Joubert…or perhaps it was the UN flag on her sleeve he was staring at.

If he doesn’t like it, Alexander thought viciously, then screw him!

Alexander hated the very idea of US Marines on Mars, hated the politics, hated the twisted, jingoist, nationalistic interests that pretended that such things were necessary. They had come to Mars to do science, vitally important science, with the discovery of the Cydonian ruins, and troops were only going to get in the way.

Well, maybe they’d be able to ignore them. After all, it wasn’t like there was a war on.

TWO

VIDIMAGE—JANICE LANGE AT NET NEWS NETWORK ANCHOR DESK.

LANGE: “In Geneva, today, President Markham concluded his fifth straight day of talks with UN Director General Villanueva, announcing that, although much work remains before the outstanding differences between the United States and the United Nations can be fully resolved, he is confident that real progress is being made.”

VIDIMAGE—THE PRESIDENT ADDRESSING A CROWD OF REPORTERS AND NETHAWKS.

PRESIDENT MARKHAM: “The United States of America is not now, nor has it ever been, engaged in any plot or cover-up involving the Martian artifacts. The joint US-Russian expedition to Mars is carrying out its research and investigations for the benefit of all humankind. We welcome the presence of UN observers and scientists at Cydonia. We welcome their assistance. The discoveries made there so far are…are astonishing in their implications for humanity, for everyone on this planet, and there’s enough work there that needs doing for us to be very happy when anyone offers to lend a hand.”

VIDIMAGE—DEMONSTRATORS OUTSIDE THE UN HEADQUARTERS SHOUTING, WAVING FISTS, AND DISPLAYING SIGNS READING “US MILITARY OUT OF SPACE!” AND “ALL POWER TO THE UN!” LONG SHOT OF PRESIDENT MARKHAM LEAVING BALCONY AS SOME DEMONSTRATORS THROW STONES AND UN POLICE STRUGGLE TO MAINTAIN A PERIMETER.

LANGE: “Large numbers of demonstrators protested the president’s Geneva visit outside UN Headquarters.”

VIDIMAGE: A PROTESTER, A WOMAN WITH A SIGN READING “US STAY HOME.”

PROTESTER (in translation): “America’s been grabbing the world’s resources for years! Now they’re trying to rape the other planets like they’ve raped the Earth! Well, we’re here today to tell them that we’re not gonna stand for it anymore!”

VIDIMAGE—JANICE LANGE AT TRIPLE-N ANCHOR DESK.

LANGE: “In other news today, Secretary of State John Matloff rejected as ‘absurd’ renewed calls for a UN-mandated plebiscite to determine the political future of the American Southwest. Representatives of the Hispanic America Alliance told reporters today that there would be no peace for America until the formal creation and recognition of the nation of Aztlan.”

VIDIMAGE—RIOTERS IN DOWNTOWN LOS ANGELES OVERTURNING A POLICE CAR AND THROWING STONES, AS TROOPS MOVE IN BEHIND CLOUDS OF TEAR GAS.

LANGE: “HAA members seek the creation of the new state from territories in Northern Mexico and from the states of California, New Mexico, Arizona, and Texas. Armed confrontations in the region between HAA protesters and military and police authorities have so far resulted in at least two hundred deaths….”

WEDNESDAY, 9 MAY

Cycler Spacecraft Polyakov

1546 hours GMT

“How’s it working now?” Garroway asked, slipping into the seat on the control deck next to Reiner. He didn’t like microgravity and was glad to get back to a place where up was up and down was a place you could sit.

The Navy astronaut looked up at the monitor. “Seems to be fine, now. Vid and sound.” He cocked an eyebrow at the Marine. “Underpants?”

“T-shirt.”

“Man, nice work if you can get it. Who was it?”

“Doesn’t matter,” Garroway lied.

It was an open secret with the cycler’s crew that passengers frequently used the storm cellar as a place for some precious, hard-to-get privacy. Different commanding officers handled the problem in different ways. Many continued to adhere to the old policy, born of NASA’s long-standing dread of bad publicity, of forbidding sexual liaisons during extended space missions; others reasoned that liaisons were going to happen no matter what the rule books said, and so long as they didn’t create problems for the crew or mission as a whole, they were probably best ignored.

Normally, Garroway wouldn’t have been interested in how the other cycler passengers passed their too-plentiful free time, but he was still angry at the realization that the storm cellar’s occupants this time had been Alexander and the Joubert woman. Damn it all, the political situation was confused enough right now, without those two attempting their own brand of détente.

Reiner was obviously still interested in the identities of the two up in the cellar, and Garroway decided he wanted to avoid the issue. He moved his chair so that he could peer across Reiner’s shoulder at the screen. “Let’s have a look.”

Colonel Lloyd was floating at the far end of the crowded compartment, while the enlisted Marines were gathered into two lines running the chamber’s length. Their torso armor had almost perfectly blended with the white bulkheads, with random, dark olive streaks where the active camouflage was picking up arms and legs from nearby Marines. Each Marine had his or her assault rifle hanging in the air in front of him, together with a small cloud of metallic pieces, rods, springs, and oil-glistening parts.

Reiner turned up the gain on the volume. “…faster, people,” Lloyd was saying, his voice a drill-field growl. “Faster! The enemy is not gonna wait for you. Pick it up, pick it up!”

Hands flew as the Marines snatched pieces out of the air, each movement precise, smooth, and almost machinelike in its control. They appeared to be reassembling their rifles, and the number of floating stray parts steadily dwindled.

One Marine, Staff Sergeant Ostrowsky, completed the drill and brought her assembled rifle to port arms with a sharp slap as her hand smacked the plastic stock. Two more finished up—slap-slap!—an instant later, and then all of the Marines were bringing their rifles up to signal completion in a ragged chorus of skin on plastic. It was a remarkable demonstration, Garroway thought. In microgravity, even the slightest movement tended to give you a push in the opposite direction, and many rapid movements could accumulate a lot of drift or spin if you weren’t careful. The Marines of the MMEF appeared to have mastered the art of balancing move with move to keep their bodies more or less motionless.

Lloyd waited until the last Marine snapped home the bolt and brought the weapon to port arms, then touched a button on his wrist-top. “Not good enough, people,” he growled. “Not good enough by thirty seconds!”

“Damned robots,” Reiner said. When Garroway looked at him, he shrugged. “Sorry, Major, but it seems like such a waste. Like close-order drill, you know? Great back when armies lined up in nice neat rows and had to go through loading and firing by the numbers, like two or three hundred years ago, but pretty useless in a modern war.”

“I’d say it’s a pretty good exercise of self-control and discipline, wouldn’t you?”

Reiner chuckled. “Well, the next time I need a rifle stripped down and put back together in zero G, I’ll sure as hell know who to go to. Shit, why’s he making them wear armor in there? O1’ Poly’s been around her circuit two and a half times, now, and she hasn’t been attacked by space pirates once!”

On the screen, Lloyd was grinning at the Marines with what could only be described as sadistic anticipation. “All right, people. Since you keep falling asleep at this evolution, we’ll try to make it a little bit more challenging. We’ll do it again!” Suddenly, the screen went black. “In the dark! Ready…begin!”

The sound of clicking and snapping clattered from the speaker, until Reiner dialed down the gain once more.

Garroway thought about replying to the astronaut’s jibe, something about discipline under pressure, or even about needing to learn how to work in the cumbersome armor without letting it turn you clumsy…but decided at last that it wasn’t worth it. Reiner was Navy, and there were some things a squid just couldn’t understand.

The fact was that Reiner had hit pretty close to the mark, talking about drills evolved from combat necessities centuries old. There’d been a lot of talk lately about the US Marines becoming obsolete, and scuttlebutt aplenty about the reason for this deployment. Garroway was pretty sure the MMEF was a political chip in some unseen, high-stakes game, a means, possibly, of keeping the Corps alive when a number of very powerful people and organizations wanted to kill it. And it was true that President Markham was beating the drum pretty loudly during his reelection campaign this year—“our brave young men and women, serving America’s interests far from this blue Earth….” The United States was increasingly isolated in a hostile world, and her citizens were clinging tightly to symbols of American might, tradition, and security.

None of which addressed the real question. Was the Corps obsolete? Didn’t the Marines simply duplicate functions now handled by the Army?

Well, maybe they did. What of it? Garroway was mildly surprised to find that he didn’t really care, one way or the other, what became of the Corps.

It wasn’t that he disliked the Marines. Quite the opposite, in fact. The Marines had introduced him to advanced electronics, paid for an outstanding college education, and let him work on some absolutely fascinating projects, from communications software to advanced AI. The trouble was that he’d pretty much reached the end of the opportunities that the Corps could provide. How, he often joked with his daughter, could the Corps possibly top a trip to Mars? In fact, he’d been passed over for promotion twice now, a sure sign that he was never gonna make it to light colonel. He was at the top of his field inside the Corps, but there was no place else to go. To realize his true potential, he’d have to reenter the world of civilians. His background would land him a position at Pittsburgh’s Moravec Institute easily—he’d worked there for a time on a government-sponsored AI project, five years ago, and he knew some people who could pull some strings—but right now he was less interested in continuing with AI communications software than he was in the Bahamas…specifically in opening a charter hydrofoil and submarine tour boat service for rich vacationers. That was the extent of his ambition at the moment, a dream that had very little to do with the Corps.

More than one of the people he’d worked with over the past few years, people including Colonel Lloyd, had accused him of going ROAD—Retired On Active Duty—marking time, in other words, until he was a civilian once more.

Well, maybe that was true, in a way. It was a bit ironic, actually, that he should find himself a member of the MMEF, occupying a billet that a few thousand other Marines would have given their teeth for, and he didn’t really want to be here. Two more years—a planned fifteen-month deployment on Mars, followed by a seven-month transit home aboard the cycler Columbus—and he’d be out of the Corps. With all the military cutbacks lately, he shouldn’t have any trouble resigning his commission, and a month or two after that he’d be on the beach at Nassau, alternately soaking up the sun and soaking the rich tourists.

“Well,” he said at last, after a long silence had passed, “all the routine traffic is up-to-date. I guess I’ll head back to the hab.” He stretched. “I still have five minutes’ shower credit left over from last month, and I think I’m gonna luxuriate.”

“Enjoy,” Reiner replied. “And thanks for your help. I don’t know what we’ll do if the cameras go out in the shelter again on the Earth-bound leg.”

“Oh, you’ll manage, I’m sure.” He jerked a thumb at the monitor. “You won’t have so many passengers on board. Maybe the romantic ones can use their cubicles, like normal folks.”

“Nah,” Reiner said, shaking his head. “Zero G is too much fun.”

“Oh? How would you know?”

“Classified information, Major. I’ll never tell.”

Garroway caught a transport pod and took it down to the hab-mod level, where the spin gravity now measured .38 Gs, the same as on the surface of Mars. There were two hab modules attached to the outermost rack of the cycler’s A-arm. His quarters were in Hab One, which was reserved for officers, female Marines, and civilian passengers. The twenty-two enlisted male Marines were quartered together in Hab Two’s tiny open dorm. Crowding was bad in both habs—worse in Two than in One. At least the Marine officers were quartered two to a compartment. He shared his semiprivate, closet-sized quarters with the MMEF’s supply officer, Captain Gregory Barnes.

As he stepped through the lock module into Hab One’s small rec lounge, he nearly collided with Mireille Joubert. “Major! Hallo. I wanted to thank you for your, ah, timely warning.”

“It was nothing.” He’d not meant for his voice to sound cold, but it did anyway.

“It would have been most embarrassing….”

“Excuse me, Miss Joubert—”

“It is Doctor Joubert, but I wish you would call me Mireille.” She cocked her head to the left. “We have made this voyage all the way from Earth, seven months, now, and we have not had much opportunity to get to know one another. Perhaps it is time we did so.”

Garroway raised an eyebrow. “I don’t think that would be such a good idea, ma’am,” he said, a little stiffly.

“Why? Because I work for the UN?”

“Isn’t that enough?”

“I am not one of Colonel Bergerac’s thugs,” she said, lifting her chin. “I am a scientist, an archeologist. Whatever differences your nation might have with the UN, they should not affect you and me.”

“Mmm. To tell you the truth, Dr. Joubert, I feel more kinship with Bergerac’s ‘thugs,’ as you call them, than I do with you and your UN observers. In my opinion, it’s misguided UN policy and the demands being made by your bureau that have created this crisis. Not my government. And not the MMEF.”

“Did I say that it was?”

“The opinion the UN has about Marines on this expedition is well enough known, I think. As are the UN’s opinions about American sovereignty.” He gave her a wintry smile. “Funny. I always thought you French would fight to the death to keep your national sovereignty.”

“And who says we do not, monsieur?” she flared back. “France is still free. Still sovereign…within very broad and liberal boundaries.”

“If that’s your story, you stick to it. Now, if you’ll excuse me, they warned us back at Vandenberg that we shouldn’t discuss politics with you people.”

Pushing past her, he entered his cubicle and pulled the accordion-pleated door shut.

What he didn’t need right now was to be reminded about politics. The political situation on Earth seemed to be worsening almost week by week, with the increasing pressure to cave in to UN demands. Russia and the United States of America were the last two major powers on the planet that had not signed the UN Reorganization Charter of 2025. That document called for the establishment of a United Nations government that would have jurisdiction over the national governments of the world, the gradual abolition of all national militaries, and new international laws and regulations governing the exploitation, shipment, and sale of the world’s resources.

The reasons for the growing concern—no, the growing world panic—were easy enough to see. The problems had been around for a long time, growing steadily, growing as quickly, in fact, as the world’s population, which currently stood at something just over nine billion people. Global warming, the subject of speculation as far back as the 1980s, had proved to be not speculation but hard fact for forty years or more. Sea levels had risen by half a meter the world over, and they were expected to rise by another meter or so before the century’s end. Rising sea levels—and disastrous storms—had killed millions, and driven tens of millions more into refugee status. Precious agricultural land in Bangladesh and coastal China and the US Gulf Coast had been swallowed up by the advancing tides. As nations like the United States and Russia finally ended their dependencies on fossil fuels and polluting industries, the poorer nations of the world had finally reached the point where they could become rich…but only by embracing the air-, land-, and sea-destroying industries that the US and others were now abandoning. Acid rain generated by China was destroying forests in western Canada, and the Amazon rain forest was all but gone now, replaced by ranches and acid-pissing factories. The last of the oil was swiftly vanishing; other raw materials vital to civilization—copper, silver, titanium, cobalt, uranium, a dozen others—were nearly gone as well. Things were bad enough that the Geneva Report of 2030 had declared unequivocally that all of the world’s nations had to be under direct UN control by 2060 if certain key controls on population and industry were to be successfully put into place.

No wonder the whole world was casting the US and Russia as villains, holdouts selfishly clinging to outmoded sovereignty simply because they feared a little thing like dictatorship….

Garroway wasn’t sure what the answer was, wasn’t even sure if there was an answer. The US, though, had been arguing for years that two new factors were about to break the deadly cycle of poverty and scarcity on Earth once and for all, if the industrialized nations of the planet would just cooperate long enough to make use of them.

The first was the wholesale industrialization of space, where power from the sun could be collected on a never-before-imagined scale and applied to industries that should not be allowed to pollute or endanger the planet. In another few years, perhaps, orbital industries could start making a real difference in the mess on Earth. The question was whether or not they would be in time….

The second factor, of course, was the discovery of artifacts on Mars, artifacts representing a technology that was old five hundred thousand years before humans had domesticated animals, developed an alphabet, or dreamed of riding ships into space. The Martian artifacts, the discoveries at Cydonia, in particular, in the shadow of that huge and enigmatic Face, were the reason humankind had at last ventured to the red planet in person.

They were also, unfortunately, the reason the Marines had been sent to Mars.

“Storm Cellar”

Cycler Spacecraft Polyakov

1602 hours GMT

“All right, people,” Colonel Lloyd bawled. “I’m gonna have mercy on you poor slimeballs. Report back to the barracks hab and get squared away. You have one hour before I pull personal inspection. Then chow. Right? Gunnery Sergeant, take over this detail.”

“Aye, aye, sir!”

“Dismissed!”

Lance Corporal Frank Kaminski looked at his buddy, Corporal Jack Slidell, and grinned. Slider grinned back, then reached above his head to one of the white storage modules strapped to the storm-cellar bulkhead and gave it a loving pat. The readout on the module said BATTERIES, GERMANIUM-ARSENIDE. “Hey, Ski!” Slidell called out. “Wanna quick charge?”

“Shit, Slider!” Kaminski said. He glanced toward the hatch, where Gunnery Sergeant Knox and Staff Sergeant Ostrowsky were ushering Second Section through to the transport pod. “Ice it, huh?”

Slider just laughed. “Yeah, I’ll ice it. I could use a nice cold one.” He rotated in the air, catching Ben Fulbert by eye. “How about it, Full-up? Ready to party?”

Kaminski glanced at the other Marines still in the storm cellar. Sometimes, Slider could be just a bit too brash for his own good…and if he screwed things for them now, just a few days out from Mars…

“Hey, Slider!” Ellen Caswell said, floating up next to them and catching herself with one hand on the bulkhead. “You and Ski got extra duty tonight, capische?”

“Aw, fuck,” Slider snapped back. “Again? Fuck this shit….”

“Fuck it yourself, Slider. You two can clean out the head cubicle before taps.” She reached out and thumped his breastplate, right above the garishly scrawled Mange la merde. “The Man didn’t like your graffiti. Especially with a French national present.”

Slidell grinned at her around the wad of gum in his mouth. “Yeah? And what was that Frenchie civilian doin’ up here, anyway? Diggin’ for buried treasure?”

“The head, shithead. Make it shine. And scrape that shit off your shell.”

He tossed her a jaunty mock salute. “Aye, aye, sergeant, sir, ma’am!”

Kaminski sighed. After seven months, he was getting to know the tiny lavatory facility in the enlisted barracks very well. Slidell was his fire-team partner, and Corps discipline held both men responsible for infractions that reflected on the fire team as a whole. Hell, Fulbert and Marchewka were probably giving silent thanks that the shit detail hadn’t hit the entire squad. Slidell had a peculiar talent for drawing fire.

“Ice it down, Slider,” Kaminski said. “We’re in enough trouble already.”

“Shee-it,” Slidell drawled as Caswell flexed her knees and launched herself across the compartment toward the hatchway. “What’re they gonna do, send us to fuckin’ Mars?”

Hang on a little longer, he told himself. Things’ll be better when you hit dirt. Space was short, and tempers frayed in a situation where, paradoxically, there were too many people for the available space and too much work for the available people. The current TO&E for a Marine weapons platoon called for five-man squads—a pair of two-man fire teams and a squad leader—organized two squads to the section, two sections to the platoon. Kaminski was in First Squad, First Section; Slider, Sergeant Marchewka, and Lance Corporal Ben Fulbert were his squadmates, while Sergeant Ellen Caswell was both First Squad leader and First Assistant Section leader. Gunny Knox also wore two hats, as First Section leader and as Lieutenant King’s assistant platoon leader.

With so small a force—a weapons platoon of twenty-three men and women, reinforced by a headquarters element of seven more—there was lots of double-hatting going on, and the Marines, rather than being mere passengers on the cycler transport, were expected to do their share of maintenance, cleaning, and general scutwork. The real problem, though, was the fact that the MMEF platoon was so damned top-heavy in the ranks. The lowest rank aboard was E-3—lance corporal—and there were lots of corporals and sergeants, more than was usual for a typical weapons platoon. And when shit flows downhill in the military, it lands on the low man on the pole.

Part of the deal, in fact, was that all personnel in the MMEF would keep their current ranks until the end of the mission, which was expected to last the better part of two years, a measure designed by some desk-flying bureaucrat Earthside to keep the platoon from getting even more top-heavy than it was already from sheer time-in-grade attrition. Where they were going, there were no replacement depots or work pools to replace the lucky SOB who made E-4. That wasn’t really as bad as it sounded. All of them were getting flight pay, hazardous-duty pay, and hardship pay enough to more than make up for the financial shortcomings of the arrangement. When they got back to Earth, most of the guys on their first hitch, Kaminski among them, would have their four in and have the choice of accepting a double promotion—Kaminski would have a shot at sergeant—or returning to civilian life with one hell of a nice separation pay packet.

Kaminski knew what he was gonna do. Four years for him was a great plenty. He would put in his hitch, and in another 745 days he would be out of here, out of the Corps and back to being a carefree civilian.

With lots of money waiting for him, too. Surreptitiously, he reached up beneath his breastplate, tugging at his BDU blouse to make sure the flag was still wrapped around his waist. Slidell saw the gesture and laughed. “Still there?”

Kaminski nodded. “Good thing, with all these damned PIs.”

“You just keep it there, Ski, out of sight. Ha! Man, we’re gonna clean up when we get back, right?”

“Aw, fer…” Kaminski shook his head. “Why don’t you tell everyone, Slider?”

“Tell us what?” Sergeant Witek, one of the HQ element people, asked.

“Nothin’,” Kaminski said, a little nervous. There wasn’t anything wrong with what he was doing. But the other guys probably wouldn’t understand….

As far back as the Mercury program in the early 1960s, astronauts had carried small and easily transported items with them into space—toy space capsules, coins, even stamped envelopes that could be postmarked in space…items that would be worth a hell of a lot to collectors upon their return. This was a joint venture. It had been Slidell’s idea to take something that might serve as a souvenir…and Kaminski’s idea that the souvenir should be a flag, an American flag. He wore it day and night wrapped around his waist beneath his T-shirt, because if Knox or one of the other senior NCOs found it in his gear locker during an inspection, he’d be cleaning that lavatory cube all the way back to Earth, and likely they’d confiscate the flag, which would be worse. The idea was to have everyone sign it after the mission was over; Slidell claimed he knew a guy in San Diego who could put an artifact like that up for auction. God, a flag signed by fifteen or twenty of the Marines who’d actually been to Mars ought to fetch thousands….

“All right, First Section!” Knox called out. “Hit the hatch!”

Making sure his M-29 ATAR assault rifle was securely strapped to his back, Kaminski joined the other Marines as they single-filed through the hatch and out to the transport pod. “Hey, Slider? What the hell do they want with US Marines on Mars, anyway?”

“Shit, why does the brass ever do anything?” Slidell replied. “To dump on the enlisted guy.”

Which seemed as good an answer to Kaminski as any he’d heard so far.

THREE

WEDNESDAY, 9 MAY: 1705 HOURS GMT

Carnegie Mellon University

Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

1305 hours EDT

Kaitlin Garroway took the second-floor door out of Herb Simon Hall onto the elwalk and headed for Schenley Park. Two exams down, three to go, plus her final project, and then she was off to Japan. She needed to work some more on her project this afternoon, but first she needed to clear her mind. After being closed up all morning, she was eager for the sight of trees and grass and blue sky.

The weather was something she really liked about Pittsburgh, the variety of the seasons, the spectacular explosion of fall colors, the sharp joy of spring after an icy winter. The dull sameness of the weather at Camp Pendleton in Southern California, where her dad had been stationed before his junket to Mars and where she’d lived before she entered college three years ago, had sometimes made her ready to scream. She laughed. Yukio thought she was nuts, but then his part of Japan was a lot like Southern California. Small wonder he hated the winters here.

Resting her hand lightly on the railing, she ran down the steps from the elwalk to ground level and walked down the hill into the park. What exactly did she feel for Yukio? She’d liked him from the moment they’d met last fall, in the Japanese Room of the International Center, and for the past few months, they’d been spending more and more of their free time together. Kaitlin wasn’t scared of the words, “I love you,” and had certainly used them with Yukio, but did those words necessarily imply a lifetime commitment? Was she ready for a lifetime commitment?

Maybe she didn’t need to know. Maybe it was enough to know that she loved him, that she enjoyed being with him and talking with him about everything. Well, everything except politics, but then who does like to talk about politics? Her parents had never agreed on politics—that’s what her dad said, at any rate; her mother had died before Kaitlin was politically aware—and they got along beautifully. She and Yukio had just recently started talking about the possibility of a long-term relationship, and now with their upcoming trip to Japan, she found herself thinking about it a lot.

Yukio wanted to introduce her to his family, and she knew enough about Japanese protocol to know what that meant. She and Yukio both considered themselves to be Internationalists, not in the sense of wanting the UN to take over everything, but in the sense of being citizens of the world. Would Yukio still feel that way if it came to a choice between her…and his family? If his family wouldn’t accept her, would he be willing to live in the States permanently? Come to think of it, suppose they did accept her. Would she be willing to leave her country behind, to make a permanent home in Japan?

She shook her head. Too much serious thinking with nothing in your stomach is a no-good way to make decisions. She really wished she could talk to her dad about this, but somehow she hadn’t been able to tell him about Yukio, and she wasn’t entirely sure why. She hadn’t even told him about the trip to Japan. Not that she needed to, of course. She was of age, she had her own passport, and she was paying for the trip out of money she’d earned. But it had been a long time since she’d kept a secret from her father. She grinned. Usually the two of them kept secrets from others.

She reached her favorite tree, a sprawling black walnut, and sat down, first unhooking her PAD case from her hip belt. Taking her PAD out of its case, she carefully unfolded it and propped it up on her knees, keying it to download her v-mail. The usual departmental garbage—she’d have to check through it later to make sure she wasn’t missing anything important. She still hadn’t been able to write a filter good enough to catch everything she needed to see. She’d once accused Namir, the department head, of deliberately writing department memos so obscurely that a programmed filter wouldn’t be able to extract the substance. “Well, if your filter isn’t good enough, Kaitlin,” he’d said with an irritating twinkle, “perhaps you’d better write one that is.” Naturally, she’d risen to the challenge, but just as naturally, Namir had increased the obfuscatory nature of his memos. She grinned. She’d learned more about self-enhancing systems writing and rewriting those damned filters than she had in three years of classes. Namir’s method was brutal, but it worked.

Hmm, what else? A few vids from friends, nothing critical. Nothing from Yukio, but that wasn’t surprising. They’d planned to meet here after his exam, so the only reason for him to comm her would be to tell her that he couldn’t make it. Notice of the Zugswang meeting tonight. She keyed in a reply, saying that she was planning on being there. A few games of chess would be the best preparation she could think of for her physics exam the next day. More study at this point would only fry her brain.

Ooh, great, a message from Dad. Kaitlin checked her wrist-top for the current time and then tapped a key to give her GMT, the Greenwich Mean Time that all spaceships and all space expeditions ran on. Only four hours difference now that Daylight Savings had kicked in, so it was late afternoon on the Polyakov. He mostly wrote her at night. When he wrote at other times, it was usually because he had something special to say, something beyond the trivia of day-to-day life aboard a cycler bound for Mars. She snorted. As if he didn’t know full well that anything that happened on board the Polyakov was fascinating to her. She’d been space-happy since…since she didn’t know how long. At least since she saw her first Vandenberg launch, but the genesis of her space fever was a lot earlier than that.

She remembered her mother reading to her a lot when she was little. Her dad had told her that a lot of the books her mother read to her were stories about spaceships and other planets and alien beings, books she later devoured for herself. Books by Heinlein and Asimov, Longyear and Brin, Zettel and Ecklar. It was infuriating. Here her dad was going off on a trip she’d give her eyeteeth for, not to mention certain other less mentionable parts, and he didn’t care! He’d rather be on a beach in the Bahamas than on the sands of Mars! She was gonna have to comm that man a lecture. If he didn’t learn to enjoy walking where no human had walked before…well, she wasn’t sure what she’d do to him, but it wouldn’t be pleasant, she could assure him of that.

She tapped on the vid icon on her PAD. It swelled and morphed into a waist-up view of a Marine major, with the stark gray wall of his hab behind him.

“The top o’ the morning to you, Chicako,” he said with a grin, “or whatever time it is when you see this.” She grinned in return. The pet name her dad had given her when she was six and in love with everything Japanese meant “near and dear,” and only he and Yukio were allowed to use it. “Well, it’s been another exciting day in the old Poly, dodging asteroids and space pirates again. To keep from dying of boredom, I’ve actually resorted to some of those science-fiction books you gave me. The problem is, of course, that the realistic ones are boring and the unrealistic ones keep reminding me of how boring the real planet is likely to be. Take this one I’ve been reading lately, for instance.” He held his PAD up in front of him. “Red Planet by that buddy of yours, Robert Heinlein.”

Buddy of mine! Come on, Dad. He’s been dead for fifty years.

“What I’m thinking is, if there were any aliens down there where we’re going, like there are in that book, well, then this trip just might be worth something. But you know, Chicako, I just can’t see that investigating rocks is worth the investment of thirty Marines. I can’t help but feel that we’re being used somehow.” He shook his head and chuckled. “What am I talking about; of course, we’re being used. We’re supposed to be used. I guess what I mean is that we’re not being used properly. We’re not being used as a tool, we’re being used as a pawn in some vast political game that I don’t understand. But I can tell you, I don’t like it.”

He looked away for a long moment. “Something else I don’t like,” he said finally, turning back to face her. “This…uneasy dance we’re doing with the UN. I know we have to let them use our cyclers by treaty, but why we’re letting them horn in on our explorations on Mars is beyond me. Do they really think we’d hog all the goodies? I don’t know.”

“There’s something that happened today I want to tell you about. It…it disturbed me, and I’m not entirely sure why. Maybe you can help me make some sense out of it. So long, Chicako. When next you see me, I’ll be on the beach.” His mouth twisted in a wry grin. “No ocean, unfortunately, but it’ll be nice to have ground underfoot again. Till then.” His face stayed on the screen for a full second and then dissolved into a string of numbers—the rest of his message was in code.

They’d started writing in code right after her mother died. A big, grown-up seven-year-old girl didn’t really want to put down in writing that she was scared, that she missed her mommy, that she wished her daddy could be home with her instead of being stationed overseas. So her dad had taught her a simple substitution code so she could say all those things without anyone else knowing what she was saying.

Over the years their codes became more and more sophisticated, until now they were using a Beale code, guaranteed unbreakable without the book the code is based on. And that was the beauty of it. It could be any book; it was simply necessary that the two parties agree on the book and, specifically, on the edition of that book. For the Mars trip, the Garroways had agreed on a 2038 reprinting of Shogun, a twentieth-century novel about sixteenth-century Japan. Kaitlin had downloaded both the book and her own Beale code translation program to her dad’s wrist-top before he’d left for Vandenberg.

Since then he’d used the Beale code routine for a part of just about every letter he’d sent her, but in the seven months that he’d been gone on the Polyakov, he’d only used it once or twice for more than a one- or two-liner. She paged down and estimated that, decoded, the message would probably run four or five paragraphs.

Kaitlin selected the text and ran her Beale code routine, wishing she could talk to him. V-mail was great, but there were still limitations. On the other hand, if he were here in person, he probably wouldn’t talk about what was bothering him. He was a very private person. Maybe writing about whatever it was that had happened was the only way he could let it out.

As she began to read the translated text, she found herself growing cold. “Consorting with the enemy,” he called it. Just because the woman was working for the UN? What is this? It’s not as though we’re at war or anything. She wondered what her father would think of her relationship with Yukio and was suddenly very glad she hadn’t told him about her proposed trip to Japan.

A shadow fell over her PAD, and she looked up, startled. The backlit figure looming above her raised his hands in mock horror. “I didn’t do it! Honest! Whatever it was, it wasn’t me!”

She quickly tapped on the screen, hiding the message in the background. “Oh, it’s just Dad,” she said, as Yukio coiled down beside her.

“Ah.”

Kaitlin folded up her PAD and tucked it back into its case. “And just what does ‘ah’ mean?” she asked.

He smiled. “It means that occasionally experiencing a lack of harmony with one’s paternal ancestor appears not to be an exclusively Japanese trait.”