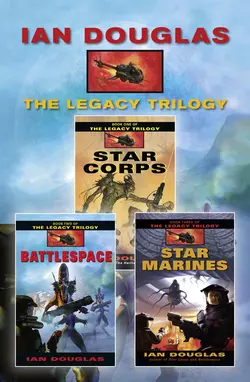

The Complete Legacy Trilogy: Star Corps, Battlespace, Star Marines

Ian Douglas

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 542.29 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: In the future, earth′s warriors have conquered the heavens. But on a distant world, humanity is in chains…This bundle includes the complete Legacy Trilogy by New York Times bestselling author Ian Douglas.Many millennia ago, the human race was enslaved by the An – a fearsome alien people whose cruel empire once spanned the galaxies, until they were defeated and consigned to oblivion. But a research mission to the planet Ishtar has made a terrifying – and fatal – discovery: the Ahanu, ancestors of the former masters, live on, far from the reach of Earth – born weapons and technology … and tens of thousands of captive human souls still bow to their iron will.Now Earth′s Interstellar Marine Expeditionary Unit must undertake a rescue operation as improbable as it is essential to humankind′s future, embarking on a ten-year voyage to a hostile world to face an entrenched enemy driven by dreams of past glory and intent once more on domination. For those who, for countless generations, have known nothing but toil and subjugation must be granted, at all costs, the precious gift entitled to all of their star-traveling kind: freedom!Includes: Star Corps, Battlespace and Star Marines