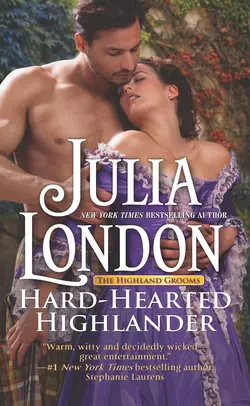

Hard-Hearted Highlander

Julia London

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 505.18 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: An indomitable governess…a brooding Highlander…a forbidden affair…An ill-fated elopement cost English-born governess Bernadette Holly her reputation, her unsuitable lover and any chance of a future match. She has nothing left to fear—not even the bitter, dangerously handsome Scot due to marry her young charge. Naive wallflower Avaline is terrified to wed Rabbie Mackenzie, but if he sends her home, she will be ruined. Bernadette’s solution: convince Rabbie to get Avaline to cry off…while ignoring her own traitorous attraction to him.A forced engagement to an Englishwoman is a hard pill for any Scot to swallow. It′s even worse when the fiancée in question is a delicate, foolish young miss—unlike her spirited, quick-witted governess. Sparring with Bernadette brings passion and light back to Rabbie’s life after the failed Jacobite uprising. His clan’s future depends upon his match to another, but how can any Highlander forsake a love that stirs his heart and soul?