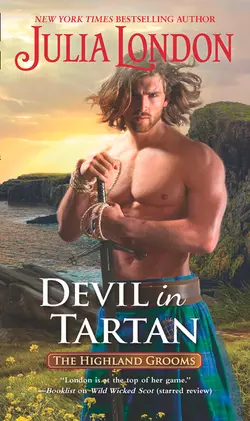

Devil In Tartan

Julia London

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 612.81 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: Peril and passion on enemy seas…Lottie Livingstone bears the weight of an island on her shoulders. Under threat of losing their home, she and her clan take to the seas to sell a shipload of illegal whiskey. When an attack leaves them vulnerable, she transforms from a maiden daughter to a clever warrior. For survival, she orchestrates the siege of a rival’s ship and now holds the devilish Scottish captain Aulay Mackenzie under her command.Tied, captive and forced to watch a stunning siren commandeer the Mackenzie ship, Aulay burns with the desire to seize control—of the ship and Lottie. He has resigned himself to a life of solitude on the open seas, but her beauty tantalizes him like nothing has before. As authorities and enemies close in, he is torn between surrendering her to justice and defending her from assailants. He’ll lose her forever, unless he’s willing to sacrifice the unimaginable…