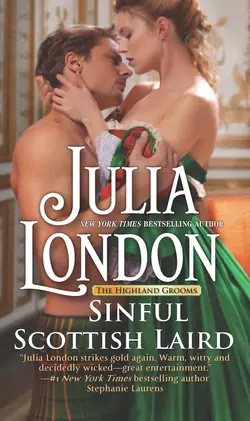

Sinful Scottish Laird

Julia London

A young widow puts her sexy suitors to the test in New York Times best–selling author Julia London's scintillating return to the idyllic Scottish Highlands.Widowed and forced to remarry in three years' time or forfeit her son's inheritance, Daisy Bristol, Lady Chatwick, has plenty of suitors vying for her hand…and her fortune. But a letter from a long-lost love sends Daisy and her young son to her Scottish Highland estate to buy time for his return. Along the way she encounters the powerful Cailean Mackenzie, laird of Arrandale and a notorious smuggler, and she is utterly –though unwillingly – bewitched.Cailean has no use for any Sassenach in his glen. But Daisy's brazen, flirtatious nature and alluring beauty intrigue him. When her first love appears unexpectedly at her estate, Cailean knows that a passionate woman like Daisy cannot marry this man. And to prevent the union, Cailean must put his own life at risk to win her heart.

A young widow puts her sexy suitors to the test in New York Times bestselling author Julia London’s scintillating return to the idyllic Scottish Highlands.

Widowed and forced to remarry in three years’ time or forfeit her son’s inheritance, Daisy Bristol, Lady Chatwick, has plenty of suitors vying for her hand...and her fortune. But a letter from a long-lost love sends Daisy and her young son to her Scottish Highland estate to buy time for his return. Along the way she encounters the powerful Cailean Mackenzie, laird of Arrandale and a notorious smuggler, and she is utterly—though unwillingly—bewitched.

Cailean has no use for any Sassenach in his glen. But Daisy’s brazen, flirtatious nature and alluring beauty intrigue him. When her first love appears unexpectedly at her estate, Cailean knows that a passionate woman like Daisy cannot marry this man. And to prevent the union, Cailean must put his own life at risk to win her heart.

Praise for New York Times bestselling author Julia London (#uad27d6f4-5b1e-5ac5-811b-b0fac26312aa)

“Expert storytelling and believable characters make the romance between Arran and Margot come alive in this compelling novel packed with characters whom readers will be sad to leave behind.”

—Publishers Weekly on Wild Wicked Scot (starred review)

“London’s writing bubbles with high emotion. Her blend of playful humor and sincerity imbues her heroines with incredible appeal, and readers will delight as their unconventional tactics create rambling paths to happiness.”

—Publishers Weekly on The Devil Takes a Bride (starred review)

“This tale of scandal and passion is perfect for readers who like to see bad girls win, but still love the feeling of a society romance, and London nicely sets up future books starring Honor’s sisters.”

—Publishers Weekly on The Trouble with Honor

“This series starter brims with delightful humor and charm.”

—RT Book Reviews on The Trouble with Honor

“Julia London writes vibrant, emotional stories and sexy, richly drawn characters.”

—New York Times bestselling author Madeline Hunter

Sinful Scottish Laird

Julia London

www.millsandboon.co.uk (http://www.millsandboon.co.uk)

For Attadale Gardens, the lovely Highland estate in Wester Ross, on the shores of Lochcarron, where I had the great pleasure of writing a portion of this book. The estate serves as the inspiration for my fictional Arrandale. A special thanks to the Laird of Attadale, who is not a strong, muscular man with dark eyes, wearing a kilt, but the lovely Joanna Macpherson. She and her husband could not have been more welcoming or their gardens more beautiful.

Contents

Cover (#u23cabb71-f048-522a-ba10-068fa489ccc8)

Back Cover Text (#ud7157d5a-39a9-570d-9fe5-fc3aae0921c7)

Praise (#u03f8fbe6-b8fc-51d6-8d75-1dc8da15799a)

Title Page (#ua4b803b3-9d3a-5414-a6a3-2893c613e2c8)

Dedication (#u4bd7ce26-b67c-50a7-9053-b2c12e26b2ec)

CHAPTER ONE (#uca300b8f-6e73-578e-8a9b-dac8fe8014f8)

CHAPTER TWO (#ub5250758-335d-503a-9086-7d17cbd4305b)

CHAPTER THREE (#ucb3790ec-d9f5-5cb6-bf40-be52e8fdf992)

CHAPTER FOUR (#u2477e0ab-e7ba-5d09-9f6a-b5a386c73c05)

CHAPTER FIVE (#u19104dcf-feef-5c9a-ad6c-71e3d0767549)

CHAPTER SIX (#ud96a3ae4-96c8-55bd-87a2-b8bb3ac991bb)

CHAPTER SEVEN (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER EIGHT (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER NINE (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER TEN (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER ELEVEN (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER TWELVE (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER THIRTEEN (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER FOURTEEN (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER FIFTEEN (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER SIXTEEN (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER EIGHTEEN (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER NINETEEN (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER TWENTY (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER TWENTY-ONE (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER TWENTY-TWO (#litres_trial_promo)

EPILOGUE (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER ONE (#uad27d6f4-5b1e-5ac5-811b-b0fac26312aa)

Scottish Highlands, 1742

Balhaire

THE COACH GROANED and shuddered along a nearly impassable road, tossing its inhabitants across the benches and back against the squabs. The young Lord Chatwick’s complexion had turned gray, and he rested listlessly against the wall.

“My poor darling,” crooned his mother, Daisy, Lady Chatwick, as she stroked his hair.

“I said from the beginning such aggressive travel would make the child ill. I pray we see a quick recovery from him.”

This sunny observation was made by Daisy’s cousin Miss Belinda Hainsworth.

“I’m well when the coach isn’t moving,” moaned Ellis.

“Dear boy, you think you are,” Belinda said and smiled sadly, as if Ellis had been made feebleminded by the travel and didn’t know his own feelings. She glanced at Daisy. “Is it not too late to turn back and spare us all?”

Too late? Yes, it was too late! They’d been traveling for an eternity and were only miles from their destination. “Too late,” Daisy said and closed her eyes.

She would explode, she thought. Shatter into a million bits of furious fatigue. Almost three weeks in transit, from London to Liverpool, then sailing up the coast through rough seas to Scotland, and then the relentless plodding past hovels made of peat and mud, past people in strange dress with small cattle and barking dogs, through miles and miles of empty landscape with a young son made ill by the motion of travel, a gloomy cousin, and no place for them to rest except the occasional mean inn.

It had been wretched.

“You look piqued, Daisy.”

Daisy opened her eyes; Belinda was studying her, her head cocked to one side. “Yes, I am. I am sick to death of riding in this coach,” Daisy fussed. “And I will be much relieved when I can remove these blasted stays.” She pressed a hand against her side with a heavy sigh, feeling the stays of her corset digging into her ribs.

At that very moment, the coach shuddered violently and sank hard to the right, and the stays dug deeper into Daisy’s side. Her son landed on top of her with an oomph, and Belinda was thrown against the wall of the coach with a cry of alarm.

“For heaven’s sake,” Daisy said, breathless.

“Madam!” someone shouted from outside the coach; the door swung open. “Are you unharmed?”

“We’re fine. Is it a wheel?”

“It is indeed,” her escort, Sir Nevis, said as he lifted her son out of the coach.

“What shall we do?” Belinda asked as she carefully backed out of the coach. “We haven’t the proper tools to repair it. We’ll be forced to camp here!”

“We shall endeavor to repair it,” Sir Nevis said as he extended his hand to help Daisy down.

She stepped gingerly onto terra firma and adjusted her corset as best she could without removing her gown and clawing the damn thing from her body, then joined Sir Nevis to have a look. A spoke had broken, and the wheel was bowing. The driver and his helper were quickly releasing the horses from their traces.

“We must elevate the coach to keep the wheel from snapping,” Sir Nevis said. He looked to the three men they’d hired at port to escort them to Auchenard. Gordons, he’d said. A mighty clan, he’d said. Daisy didn’t know how mighty the Gordons were, but she hadn’t liked the look of these three from the start. They were as thin as reeds, their clothing worn and filthy, and they looked at her like little boys staring at sweetmeats in the shop window. They were fond of whisky, and if they spoke English, she couldn’t say—they rarely uttered a word, and when they did, their accents were so heavy that she couldn’t make anything out. Now, they stood aside, eyeing the broken spoke with disinclination.

“Madam, if you and his lordship would take shelter beneath those trees,” Sir Nevis said, nodding to a stand a few feet from the coach. “This might take some time.”

Might? Daisy sighed wearily. She was not new to the world of coach travel and rather imagined it would take all day. She looked around them. It was a sun-drenched day, the air uncomfortably warm. Even the plumes atop their coach were wilting. There was no shelter, nothing but miles and miles of empty rolling hills and swarms of midges as far as one could see.

Ellis had dipped down to examine a rock. At least some pink had returned to his complexion; she was thankful for that. “See, Mamma,” he said, and held up a rock. “It’s pyrite.”

“Is it?” she asked, leaning over to peer at a rock that was yellowish in color. “So it is,” she agreed, although she had no idea what sort of rock it was. She looked back over her shoulder at her retinue—three servants and a tutor; Sir Nevis and his man, Mr. Bellows, who had accompanied them from London along with the two drivers; a pair of wagons under Mr. Green’s care, loaded with boxes and trunks that carried their things; and a smaller chaise in which Mrs. Green and the housemaid rode.

It was as if she were leading a band of gypsies across the Highlands.

A movement at the lake caught her eye, and Daisy noticed the Gordons at the shore. Well, yes, of course, they should swim, the poor things. Perhaps wash a bit of the dirt off them while her men toiled in the hot sun to repair the wheel. How much had they paid for that trio of scoundrels?

“We can’t possibly be forced to camp here,” Belinda said, fanning herself. “There is no shelter! We leave ourselves open to marauders and thieves.”

“Belinda, for God’s sake, will you stop,” Daisy said wearily. “I have listened to your complaints until I can bear it no more. There is nothing to be done for our predicament. We are here. We will not die. We will not be harmed. We will not be set upon by thieves!”

All those years ago when Daisy had been a new bride, with her mother gone and no one to advise her, she’d promised her maternal aunt on her deathbed that she would look after Belinda. Of course she would—Daisy loved her childhood playmate. She’d just never realized how doleful her cousin could be until she was under her roof.

Belinda said nothing to Daisy’s rebuke. In fact, she seemed to be staring at something behind Daisy. With exasperation, Daisy drawled, “What is it now? Marauders?” She turned around to see what had captured Belinda’s attention, and her heart sank to her toes—five figures in highland dress were galloping down the hill toward them.

“Not marauders,” Belinda said, her voice trembling. “Smugglers. I’ve heard it said they hide in these hills.”

And with that remark, the air was snatched cleanly from Daisy’s lungs.

There was a sudden and collective cry of alarm as the rest of Daisy’s entourage noticed the riders. It was as if someone had fired several rounds into their midst; people ran, grabbed up their things as they raced to hide behind the wagons.

“Lady Chatwick!” Sir Nevis shouted. “Take shelter in the chaise!”

He had drawn his sword, and together with Mr. Bellows, stood with his legs braced apart, facing the intruders, prepared for battle. Belinda was already moving, grabbing at Ellis’s arm as he lined up the rocks he’d collected and dragging him toward the chaise.

But Daisy? She didn’t move. She was too stunned to move. Utterly paralyzed with fear and exhilaration, on the verge of screaming in terror or laughing hysterically at the absurdity of it all—of course they would be set upon by highland thieves! This was precisely the disaster Belinda had predicted all along.

Something about the notion of disaster made her move; she whirled about to summon the three Gordons, but they were no longer on the shores of the lake. They had fled. Fled! Her heart leaped to her throat, and she whipped back around...almost expecting the Gordons to have joined the riders.

The Highlanders had slowed their mounts, approaching with caution now. One of them—a woman, it appeared—spurred her palfrey to lope ahead of the others. Roving bands of thieves were not led by women, were they? Perhaps, then, this was not what it seemed.

The bark of gunfire startled Daisy so badly that she dropped to all fours on the ground before realizing that Mr. Bellows was the one who had fired his musket. But his aim had erred, and the shot pinged off a tree to the right of the band of Highlanders.

One of the riders abruptly spurred his mount forward, catching the palfrey’s bridle before the woman rode headlong into buckshot, and reined her to a hard stop. “For God’s sake, put down your weapon!” he roared in English. “Bloody hell, lad, you might kill someone, aye?”

Mr. Bellows aimed his gun at the man. “We’ve no use for highwaymen or Jacobites, sir! If you do not ride on, I will aim for the spot between your eyes!”

Daisy found her feet and hurried forward with the vague intention of seeking shelter inside the listing coach. But she paused at the driver’s seat and peered over the footrest as another of the men rode forward to meet the first and spoke in the language of the Scots.

The first man answered, his voice low and soft. Whatever he said prompted two of his companions to laugh. But he did not laugh. He sat tall and stoic on that horse, his mien fiercely proud, his gaze shrewd and locked on Sir Nevis and Mr. Bellows. He looked to be a head taller than the others. He was broad shouldered and square jawed, with thick auburn hair that he’d tied at his nape. His appearance was so rugged, so overwhelmingly masculine, that Daisy’s blood raced in her veins in a mix of absolute terror and fascination. He looked stronger than any man she’d ever seen, as if he alone might have been responsible for carving these hills from the granite landscape.

Something sharp and hot waved through Daisy, making it impossible to breathe, much less move.

He spoke to the woman, who clearly did not care for what he said, judging by the way she jerked her gaze to him and responded in a heated tone.

“Do as I tell you, lass,” he said, his voice unnervingly calm. “Fearful men fire without warning and without aim.”

The woman muttered under her breath, but she turned the palfrey about and put herself behind the other three men.

Now the man nudged his horse forward, his gaze still fixed on Mr. Bellows and his gun.

“Come no closer!” Mr. Bellows warned him, then looked around. “Gordon, where are you? Why do you not do something?” he shouted.

The man chuckled. “The Gordons willna help you now, lad.” One of the riders muttered something that made the others laugh. They weren’t the least bit afraid of Mr. Bellows’s gun or the fact that they were outnumbered, Daisy realized with a slam of her heart against her ribs. They were...amused.

Like a cat, the man’s attention suddenly shifted to his left; Daisy followed his gaze and noticed that the drivers had crept around one of the wagons, both holding muskets. He sighed loudly as the drivers both leveled their sights on him. “We’re no’ highwaymen,” he said brusquely. “Put down your guns, aye? I donna care to kill you on what’s been a bonny afternoon thus far.” He swung off his horse; everyone in Daisy’s party took a step backward.

But not her, because Daisy had clearly lost her fool mind. She was keenly aware that she ought to be seeking shelter, hiding Ellis, finding something with which to defend herself...but she couldn’t tear her eyes away from the perfect physical specimen of a man. A bolt of feral desire shot down her spine, unlike anything she’d ever felt, as she studied him standing there, his weight cocked on one hip as he yanked his gloves from his hands. He wasn’t handsome in a conventional way. His looks were fine enough, she supposed, but it was him that enthralled her—his presence, his carriage and the veritable confidence that exuded from him.

He was wearing the plaid about him, and his legs, Lord in heaven, his legs shaped by sinewy muscle, were covered in a sort of red-and-white plaid pair of stockings, tied just below his knee with garters. He was tall, but not overly so, and lean, but burly, too. He was clean shaven, yet his hair appeared untamed, even tied at his nape as it was. He was so calm, so unruffled—he projected palpable power.

Had she been any other place, Daisy might have fanned herself. As it was, she was on the verge of swooning. She was astonished by her physical response to this man who, for all she knew, was a murderer, a smuggler, a thief—but damn her, in that frenzied moment of lust and fear, she could not think of a single other time she had been so completely enthralled by one man.

Now that he’d removed his gloves and tucked them into the plaid somewhere, he moved with great ease toward Mr. Bellows as Sir Nevis circled around, his sword raised, prepared to attack.

“Mi Diah, look around you, aye?” the Scotsman said. “Does a lady and gentlemen in leather boots rob coaches? Here? Where scarcely anyone resides?” He swept a thick arm to indicate the vast, untouched land around them. “We are no’ Jacobites, nor highwayman. But if we were, we’d shadow the road to Inverness. No’ this seldom used road.”

That seemed like a perfectly reasonable explanation to Daisy. Wasn’t it? She wanted to believe him, but her nerves, always so pragmatic, warned her that this entire situation might be planned. Perhaps the Gordons led them here so that these men could rob them. Now her heart began to pound with the possibility of danger, her palms dampening, her breath shortening. And yet she didn’t hide—she slipped around the coach while Mr. Bellows nervously kept his gun sighted on the man.

“We are charged with the protection of Lady Chatwick and her son, and we will not hesitate to give our lives if necessary, sir! Do not come closer!” Mr. Bellows’s hand shook.

If these Scots were in cahoots with those rotten Gordons, her party would be outnumbered at any moment. She was struck cold with the image of dozens of them coming down from the hills to pillage them, just as Belinda had predicted.

“We mean only to help, aye?” the Scotsman said. His voice wasn’t as heavily accented as the Gordons. In fact, his speech sounded as it was tinged with a bit of an English accent.

He lifted his hands shoulder high to show he was unarmed. “We’ve no desire to harm you; I give you my word as a Highlander and a gentleman.” He didn’t tremble, didn’t seem to be the least bit concerned. He seemed only impatient, as if he wished this meeting to be done.

“You expect us to believe it?” Mr. Bellows snapped.

“There is no’ a man among us who is inclined to haul so many boxes and trunks down the road.”

One of the riders behind the Scotsman spoke in the Scots language, and when he did, Mr. Bellows made the mistake of looking at him. In the space of no more than a moment, the Scotsman lunged so quickly for the barrel of the musket that Daisy couldn’t help but sound a yelp of alarm. He yanked it cleanly from Mr. Bellows’s hands and twirled it around in one movement to train it on him. “You’ll tell your companions to put away their firearms now, aye?” he asked, his voice deadly in its calm.

Daisy believed she would be bargaining for her son’s safety at any moment and frantically thought what to do. Should she find him and run for the lake? She glanced toward the chaise where Ellis was hiding, and saw Mr. Green furtively begin to lift his musket and take aim. Mr. Green, her groundskeeper, who’d likely never before fired on another man. “No!” she cried out inadvertently, the desperate sound of her voice startling her. “All of you! Do as he says, sir, please.”

The Scotsman did not take his eyes from Sir Nevis. “Heed your lady.”

“I urge you, madam, put yourself in the coach!” Sir Nevis shouted.

“If these men intended to rob us, would they not have already done it?” she asked, tripping over the traces of the chaise as she picked her way around the coach, desperate to avert a crisis. “Would not our hired men have interceded? I think he speaks true.”

“Ah, a voice of reason, then,” the Scotsman drawled.

There was no reason in Daisy at all—she had no idea what these men intended and spoke only with the frantic hope of avoiding bloodshed. “Please, Sir Nevis, tell your men to lower their sights,” she begged. “We want no trouble here.”

Sir Nevis jutted out his chin, but he turned slightly and nodded at the other men, and slowly, suspiciously, they lowered their guns.

The Scotsman smirked, then twirled the musket in one hand so that the butt was facing away from him and handed it to Mr. Bellows. “Now...might we help you repair the wheel?” he asked as if the tension had not just simmered so menacingly between them. As if none of them had, only moments before, feared for their lives.

“That is not necessary,” Sir Nevis said stiffly.

The Scotsman shrugged indifferently. “Aye, then. We’ve no desire to toil under the hot summer sun.” He turned as if he meant to depart, but he caught sight of Daisy and he hesitated, his eyes locking on hers.

Daisy’s breath quickened; her first instinct was to step back, to run. Her second instinct overruled the first, however, for he had a pair of astoundingly blue eyes. Cerulean blue. She was moving without thought, stepping away from the coach as she nervously pressed her damp palms to the front of her gown.

His heated gaze slowly traveled the length of her, his eyes like a pair of torches, singeing her skin as he took in every bit of her gown and the tips of the shoes that peeked out from beneath her hem. Then up again, to her bosom, where he unabashedly lingered, and finally to her face.

Daisy self-consciously brushed her cheek with the back of her hand, wondering if she looked dirty or worn.

He continued to stare at her so boldly and unapologetically that Daisy couldn’t help but smile uneasily. “Ah...th-thank you for your offer,” she stammered. What the devil was she to say in this situation?

He stared at her.

“Madam, I must insist that you return to the chaise with your lady to wait,” Sir Nevis begged her.

“Yes, I will,” she assured him, but she made no move to do so, not even when she heard Belinda call for her. She simply could not look away from the Scotsman.

“Who are you?” he suddenly demanded.

“Me?” she asked stupidly, but then she remembered herself and stepped forward, her hand extended, and sank into a curtsy with the vague idea that if all else failed, perhaps civility might work. “I beg your pardon. I am Lady Chatwick.” She glanced up, her hand still extended. The Scotsman scowled down at her. He showed no inclination to take her hand.

Daisy self-consciously rose. She’d never seen eyes so blue, she was certain of it—the very color of an early spring day. “I do so appreciate your offer of assistance. We’ve come a very long way and have not seen roads as bad as these.”

His gaze narrowed menacingly, and he took a step toward her. And another. He tilted his head to one side, studying her, as if she were a creature he’d never seen before. “What is an English noblewoman doing in these hills?” he demanded, his voice tinged with suspicion.

“We are to Auchenard,” she said. “It is a lodge—”

“Aye, I know what it is,” he said. “No one goes to Auchenard now but rutting stags. What business have you there?”

She was slightly taken aback by his crass comment. “Ah...well, Auchenard belongs to my son now. I thought he should see it.”

He frowned as if he didn’t believe her. His gaze fell to her lips, and there it lingered.

Daisy’s blood fired and flooded her cheeks. She nervously touched a curl at her nape. “I beg your pardon, but might I know your name?”

He slowly lifted his gaze. “Arrandale.”

“Arrandale,” she repeated.

He took another sudden step forward, and now he stood so close that she had to tilt her head back to look up at him.

“Stand back!” Sir Nevis shouted, but the Scotsman ignored him.

Daisy’s heart was seizing madly in her chest. She could clearly see the emerging shadow of a dark beard and the dark lashes that framed his eyes. And the nick of a scar at the bridge of his nose, another one on his jawline. She looked at his mouth, too, the dark plum of his lips.

“You should no’ have come here,” he said quietly. “This country is no’ safe for Sassenach women and children. Repair your wheel, turn about and head for the sea.”

Daisy blinked. “I beg your pardon, but we’ve—”

He abruptly turned his back on her and strode to his horse, swinging himself up onto its back. He said something to the others, and, just like that, they rode away, in the direction from which Daisy and her party had labored all day.

It seemed several moments before Daisy could breathe. She exchanged a wide-eyed look with Sir Nevis, who at last instructed the others. “To the wheel,” he said. “Make haste.”

“What has happened?” Belinda’s voice cried out behind Daisy. “Where have they gone?”

“Be thankful they have gone and left your purse and your virtue intact, madam,” Sir Nevis said darkly and whirled about, marching to assist in the repair of the wheel.

Daisy felt Belinda’s hand on her back. “You are shaking,” she said. “Calm yourself, Daisy. They’ve gone—you’re quite safe for the moment.”

Daisy wasn’t shaking with fear. She was shaking because she had never in her life been so bewitched by a man.

CHAPTER TWO (#uad27d6f4-5b1e-5ac5-811b-b0fac26312aa)

MORE THAN TWO hours after the Scotsman and his group had left them deserted on the road, the wheel repaired as best it could be, Daisy and her party began the arduous progress east once more.

As they bumped along, her heart still fluttered a little. She couldn’t rid herself of the image of that man. She listened idly to Belinda, who hugged the small window, peering out at the landscape, remarking on the vast emptiness and dangers lurking, but Daisy thought of him.

“I’d not be the least surprised were we attacked by those wild men,” Belinda said, shuddering.

“They didn’t seem so very wild in the end, did they?” Daisy asked. She thought of the warnings her friends had given her before she’d departed for Scotland. She’d invited several ladies over for tea. “What trouble you’ll find there, what with all the traitors among them,” Lady Dinsmore had cried. “You can’t go! I’ve heard they slaughter the English.”

“They’re savages,” Lady Whitcomb had added gravely. “They have been unnaturally influenced by the Stuarts and are quite impossibly untrustworthy! You won’t be safe for a moment among them—everyone knows the greatest prize is an Englishwoman.”

Daisy didn’t share their pessimistic view. She’d been married to a man who was himself a Scot by blood, and he had never given her any reason to believe she should fear them. Then again, she’d never seen a Scot like the one she’d encountered today.

Neither had Belinda apparently, for her head snapped around, her brows almost to her hairline. “I thank the good Lord we escaped unharmed!”

Ellis lifted his head and looked at his mother, an expression of worry on his face. Daisy smiled reassuringly and hugged him to her side. “We are safe, darling.”

She’d often privately wondered if she’d done something while she carried the boy to produce such a fretful, fearful child. What else could explain it? He was nine years old and had never wanted for anything, had no outward ailments to speak of, and yet he was so timid. Their London physician had warned Daisy a few years ago that her son suffered from a weak constitution. “No doubt he shall be sickly all his life,” he’d said as he’d closed his bag.

That news was not what Daisy had expected, and she’d looked at him with confusion. “Sickly? What do you mean?”

“Just that.” The physician had no regard for her, much less Ellis, who was old enough to understand what he’d said.

“Do you mean he will have a chronic ague?” Daisy had asked, for certainly that particular winter, it had seemed her son was perpetually ill. And then she’d led the physician from Ellis’s bedside and whispered, “Or something worse?”

The physician had shrugged and said absently, “One never knows how these things will manifest themselves.”

“I beg your pardon, sir, but that is why I sent for you,” she’d said impatiently. “So that you might explain to me what his illness is and how it may manifest itself.”

“Lady Chatwick.” The physician had sighed, as if she was testing his patience, then had said quite loudly, “You will not understand the nuances of the boy’s medical constitution. You must trust me when I tell you that he will never be a robust lad.”

Ellis had burst into tears as one might expect having just heard such a callous delivery about the state of one’s health. Daisy had known then that the physician meant only to collect his fee and didn’t care a whit for her son. “Then we have a problem, sir, for I don’t trust you at all,” she’d said, then called for the butler to dispatch the good doctor.

When she’d complained of his demeanor later that evening, her husband had chastised her for being disrespectful to the doctor.

Nevertheless, Daisy refused to believe the man’s prediction of Ellis’s future. Frankly, her son’s health was the second reason Daisy had undertaken what had become an increasingly dangerous journey north.

Robert was the first reason. If Robert had only reached her in time, this travel might well have been avoided.

She mindlessly touched his letter, kept safe in the pocket of her gown. I will come with great haste as soon as my commission has ended, he’d written her.

But not soon enough, as it turned out.

“If they don’t find us now, they’ll surely find us at this lodge,” Belinda warned, settling back against the squabs, still intent on worrying them all.

“We are perfectly safe,” Daisy said, and tried to convey a warning to her cousin with her expression, which, naturally, Belinda did not notice. Daisy smiled and squeezed Ellis’s knee. “Pay Cousin Belinda no mind, darling. It’s been a trying day for us all.”

“I am not unreasonable in my concern,” Belinda said. “We were all of us frightened by those dangerous men.”

“Need I remind you that those dangerous men offered to repair our wheel?” Daisy asked, then impulsively covered Ellis’s ears with her hands and leaned forward, whispering, “Forget that now, darling. Did you not see the gentleman? He was so...alluring.”

Belinda blinked. “The Scotsman? Alluring? Daisy!” She gasped, clearly appalled. “What is the matter with you? Scotsmen are not alluring. They are traitors to the Crown!”

Were she not so exhausted, Daisy would have argued that Belinda was not acquainted with any Scotsmen, and, therefore, couldn’t know if they were all or any of them Jacobites. Instead she was disappointed that Belinda had not noticed the man’s allure. She could not share in the observation of how a man with his extraordinary presence could be found on an abandoned road in what seemed the most remote region of the earth. With a sigh, she let go of Ellis’s ears and turned her gaze to the grimy window as Belinda began to speculate if they would be forced to camp on the road tonight.

He’d been so utterly unexpected. Daisy flushed again, thinking about the Scotsman. Oh, but she was a hopeless cause. Quite possibly even mad! She shuddered to think how foolishly beguiled she’d been, particularly in the face of what could have been terrible danger. She’d long been an admirer of healthy men, but this...this bordered on lunacy.

And yet...she hoped she might see him again one day. She would very much like to make him smile, to see the light she was certain could be coaxed from those blue eyes under the right circumstances. She quivered a little, imagining just how she might.

Oh yes, she was mad—completely and utterly mad.

This tendency to fantasy was something that had been slowly building in Daisy since her husband’s death more than two years ago. She’d since dabbled liberally in the art of flirtation in salons across Mayfair, had imagined any number of handsome gentlemen in varying degrees of compromise, so much so that now that tendency often felt impossible to control. The truth was that Daisy very much missed a man’s touch.

Her husband, Clive, had been robust when her marriage was arranged, but he’d contracted a wasting illness soon after Ellis’s birth. In the last years of his life, he’d suffered gravely, too sick to be a father, too sick to care for her as a husband ought. Now, at nine and twenty, Daisy felt desire flowing in the vast physical wasteland of her life like a river that had overrun its banks.

Her steady stream of suitors since Clive’s death were the raging storm waters that fed that river.

But the Scotsman was not a suitor, and she thought of him in an entirely different light. She closed her eyes and imagined being kidnapped by him, carried off on the back of his horse, tossed onto a bed high in some rustic castle. She imagined his large hands on her body. She imagined resisting him at first, then succumbing to his expert touch. She imagined feeling his body, hot and thick inside her, and those blue eyes boring into her as she found her release.

Daisy shifted uncomfortably.

“Are you all right?” Belinda asked.

Poof. In an instant, the image of him disappeared. “Pardon?” Daisy’s cheeks warmed as she shifted again. “Yes, I’m fine.”

“Is it your stays?” Belinda asked sympathetically. “Stays can be quite dangerous, you know,” she said, launching into conjecture about the dangers of corsets.

Daisy sank into the squabs and resolved not to think of the stranger again. She would think of London, of all the reasons she’d been so determined to leave.

Ah yes, that stream of suitors.

Her husband’s will had made London unbearable for her. It was no secret to the gentlemen bachelors about town that Lord Chatwick’s widow must remarry within three years of his death or risk forfeiting her son’s inheritance.

Clive had explained this to Daisy from his deathbed. “You must understand, darling. I should not like to see you refuse to marry again and deplete Ellis’s inheritance to live as you like. You will rely on Bishop Craig to help you find a suitable match. He will see to it that the man you agree to marry will ensure Ellis’s education in the finest institutions and will possess the proper connections for Ellis when he reaches his majority.”

Daisy had been horrified by his unexpected edict. She could scarcely embrace her husband’s looming death, much less the plans he’d made for her for after he’d gone. “I can look after him, Clive,” she’d said. “I am his mother—of course I will.”

Her husband had lost a moment in a fit of coughing, then patted her hand. “You will do as I decide, Daisy. I trust you to understand.”

But she didn’t understand. She would never understand.

Daisy and Clive’s match had been made on the basis of compatible fortunes and family interests. He was fifteen years her senior, and Daisy had been his second wife, his first having been lost in childbirth along with the child. It was the sort of match she’d been brought up to expect, and she’d been somewhat prepared for it. Duty first, wasn’t that what had been drummed into her?

But something miraculous had happened in that first year—she’d discovered affection for Clive. She’d been a steadfast and true companion, and she’d given him a son. She’d remained at his bedside when other women might have sought diversion elsewhere, and she’d held his hand when he felt searing pain rack his body. She’d been the wife she had promised him she would be.

And for her devotion, in the last weeks of his life, he’d made his final wishes known to her. Plans he’d already made. None of them included any regard for her.

Daisy had felt used and unimportant. As her husband lay dying, she’d realized that she was and always would be nothing more than a conduit to provide a son and then bring that son to his majority. That was her worth to Clive. Her feelings, her wants, were irrelevant to him.

As Daisy had struggled to keep her bitterness from coloring the days and weeks following his death, word of his final wishes began to whisper through the salons of Mayfair. The Chatwick fortune was up for bidding!

In fairness, Daisy had enjoyed the attention at first—it was a welcome change after caring for a sickly husband for so many years. She quickly became one of the most sought-after women in London...but, as it was readily apparent to everyone, not for herself. She was a widow with a fortune and a deadline for remarriage, and that was like raw meat to lions as far as the bachelors of the Quality were concerned. She could hardly keep them from her door.

As time ticked by, and the vultures flocked around her, Daisy began to distrust the intentions of anyone who came calling. She felt suffocated by it all and began to question her own instincts. Bishop Craig made the situation all the more intolerable as he began to negotiate on her behalf—without her knowledge—with men she scarcely knew. Her pleas to him to stop fell on deaf ears. “Your husband put his trust in me, Lady Chatwick. I will not let him down in this.”

There was nothing she could do, and Daisy had all but resigned herself to her fate. But then, five months ago, as if delivered on the wings of angels, came the letter from Robert Spivey. Rob.

Rob was now a captain in the Royal British Navy. She really didn’t know more about him than that, for it had been a little more than eleven years since she’d last seen him. She’d imagined he was married and surely had children of his own. She thought that he’d forgotten her altogether. Eleven years was a lifetime in loves lost, wasn’t it?

Well, she’d not forgotten him. He’d been her first love, her deepest love and her only real love.

Ah, but they’d been so young when they’d met, so hopelessly idealistic. They’d dreamed of a future together—nothing terribly magnificent, mind you, but one that suited two people consumed with each other and with love. A future that had room for only the two of them.

Lord, how naive she’d been then! She used to daydream of how they would live: in a thatched-roof cottage with window boxes filled with flowers. They would have children, too—robust, healthy children—who would run among the fields of heather. She would have a garden, and take great pride in it, entering her flowers and fruits in the village festivals. At night, she and Robert would lie in bed beside each other, listening to the sounds of their children slumbering, their dogs in their corners. And they would make love, sweetly, gently, reverently.

What silly dreams. She’d always known her path, and no amount of wishing could change it. Daisy was the only surviving child of two elderly parents, and she was the shiny bauble they dangled before titled and wealthy men. She’d known since she was a girl that she would be married to a fine family, that her marriage would consolidate fortunes and land and forge important connections. But then she’d met Robert, and she had foolishly believed that if two people truly loved each other, they would find a way to be together.

In the eyes of her parents and society, however, Robert wasn’t good enough for her. He’d even warned her he wasn’t, so much more present in the truth of their affair than she’d been. He knew that because he didn’t have a title, or any wealth to speak of, and was merely the son of a country vicar, her parents would never agree to a marriage. It was true—while she was dreaming of her idyllic life with Robert, her parents were striking the marriage bargain with Clive. Daisy’s fate had been sealed before she even knew what was in the offing.

When she found out, she’d begged Robert to elope with her, but Robert, always the voice of reason, had refused. “I would never dishonor you in that way, Daisy,” he’d said gallantly.

She’d argued with him. “Dishonor me! Take me from here, please! You love me—how can you let me go?”

But let her go he had. “You must accept it,” he’d said.

Wasn’t it funny that those were the exact words Clive would utter to her from his deathbed many years later? You must accept it.

Robert Spivey’s family had managed to arrange a commission in the Royal Navy and he’d left Nottinghamshire without even saying goodbye to her. He had forced her to accept it.

Daisy was older and wiser now, and she was determined that she’d not merely accept these things in her life. She wouldn’t accept that an old bishop would tell her who and when she had to marry. She wouldn’t accept that one of the most important decisions of her life had been tainted with a fortune that followed her everywhere she went.

And then, the letter had come. It is with sadness and grave concern that I have received the news of your husband’s passing, he’d written. Long have I kept you in my heart, Daisy. I will not lose you to another man again...

He’d written that he was sailing soon, but that his commission in the Royal Navy would end this year, and at such time, he hoped she would welcome his call to her in London.

Daisy had been astounded. Heartened. How was it possible that after all these years, her love for Robert could burn so brightly? And yet, she could feel it, along with all the hope gurgling in her. Unfortunately, he did not say when he might come to London. What did this year mean? Tomorrow? In six months’ time? That would be too late for Daisy.

She had to give Robert time to reach her and thereby put an end to the madness around her. And the only way to do that was to escape London for a time.

She had discussed the letter and her predicament with her good friend, Lady Beckinsal, who had urged her to go, to give the poor man time to end his commission and come to London to save her before Bishop Craig forced her into an unhappy marriage. “If he comes so soon as the summer, simply tell your butler to ask if he’d like word sent to you. He will wait for your reply if he still esteems you,” she’d said with great assurance.

A knock on the coach ceiling from above startled Daisy from her rumination; Belinda opened the little hatch to the driver as Daisy sat up, wincing as her stays dug into her ribs once again.

“Milady, Auchenard just ahead,” the driver called down. The coach was slowing, turning right.

Daisy braced her arms against the wall of the coach and peered out the dusty window. It was so filthy she could scarcely see, but she could make out a tower above a high wall. The vegetation next to the road was so overgrown that she couldn’t see much else. There was no livestock, no cattle, no sheep—nothing but untended meadow and forest.

A few moments later, the coach shuddered to a stop. Ellis pushed himself up and crowded in next to Daisy, peering out the window. “Is this it, Mamma?”

“It is.”

The coach door swung open; Ellis kicked the step down and then practically leaped out of the coach with more vigor than Daisy had seen from him in days. She followed her son, shook out her skirts and put her hands to her back as she gazed at the structure before her.

Belinda stumbled out after her, knocking into Daisy and catching herself with one hand on her shoulder. “Oh dear,” she said as she, too, gazed up.

“Oh dear” was the kindest thing that might be said. The old hunting lodge was much larger than what Daisy had expected, really—it looked more like a medieval castle. The stone was dark and weathered, and ivy ran unchecked and wild over half of it. Long tendrils of it danced in the early-evening breeze. There were two towers anchoring the structure on either end. The windows—a few boarded—were dark and looked as if they hadn’t been cleaned in years. There were numerous chimneys, at least two of them crumbling, and there was no smoke rising from any of them. Auchenard seemed completely deserted.

“I thought a caretaker looked after it,” Daisy said, baffled. This had not been cared for in the least—if anything, it had been abandoned.

“Ah, there you are!” The front door, large and wooden and battered by weather, opened, and her late mother’s brother, Uncle Alfonso, strode toward Daisy as the other chaise and the wagons pulled in to the drive. His full head of gray hair was tied in a queue, and his tall, slender frame was clad in a manner she’d never seen—he’d shed his coat, rolled up his sleeves and was wearing a leather apron. “At last! I thought you’d never come!” he sang out, smiling. “Ellis, my boy, come and give your old uncle a hug.”

Mr. Rowley, the longtime Chatwick butler, and a slightly smaller version of Uncle Alfonso, appeared at the door. He was dressed like her uncle, but he was also covered in dust.

He bowed. “Milady.”

Uncle Alfonso and Rowley had come a fortnight ahead of Daisy and the rest to make the lodge inhabitable for them all. By the look of things, that had been a greater task than they’d all assumed.

“How very happy we are to see you both!” Daisy exclaimed. “It’s been such a dreadful journey, I despaired we’d arrive at all.”

“I had begun to worry,” Uncle Alfonso said as he bent to kiss Belinda’s cheek. “You must be exhausted. We’ll feed you well, but first come and stretch your legs and have a look at your Highland hunting lodge,” he said as he tousled Ellis’s hair. “It’s not as bad as it appears on first sight.”

Oh, but it was every inch as bad as it appeared at first sight.

The interior of the lodge was just as deteriorated as the outside. The floors were covered with a thick layer of dust; Alfonso’s and Rowley’s footfalls could be seen quite plainly across the hall. The air stank of stale chimneys and damp peat. The cut stones that formed the walls were so thick that it was quite cold inside. Daisy supposed that the hearths must be lit every day to keep the chill at bay. And it was dark, in part because broken windows had been covered, and in part because there were no candles.

The lodge was archaic. It was nothing like the sun-dappled rooms at Chatwick Hall with their damask draperies and Aubusson carpets, marble floors and French furnishings. It was nothing like the bright and open townhome in Mayfair.

And yet, in spite of its decaying appearance, Daisy could see the rustic charm...but it would take the work of an army to dig it out.

When they had completed the tour, Uncle Alfonso led them to what he said was the great room. The ceilings, held up by thick beams, soared high overhead. He pushed aside some heavy velvet drapes, kicking up a cloud of dust that set them all to sneezing. When Daisy opened her eyes, she was greeted with an unexpectedly beautiful view of a lake at the bottom of a gentle green slope. Mist curled up from its surface in the day’s gloaming, and the hills beyond created a backdrop of dark green, gold and purple. She smiled with delight.

“All that you see belongs to you, darling,” her uncle said.

“Really? All of it?”

“All of it,” he confirmed. “It’s lovely, isn’t it?”

“There is so much work to be done,” Belinda said, folding her arms. “I don’t know where you think you’ll find the labor for it.”

“If we can’t find the labor, we will do it ourselves,” Daisy said and turned to her uncle. “Was there not a caretaker after all?”

“Oh, there was a caretaker, all right,” he said. “But I rather think he was far more concerned with his next drink than with Auchenard. You’d do as well to leave the place to sit empty than to have it cared for by the likes of this fellow.”

Daisy sighed wearily. She hated dealing with servants who did not want to work for their wages. “What do you think of our hunting lodge, darling?” she asked her son.

Ellis frowned thoughtfully. Always so serious!

“There is a room at the top of the tower that is ideal for stargazing,” Uncle Alfonso offered.

Ellis blinked. “Can you see all of them? Can you see Orion from there?”

“Orion,” Uncle Alfonso repeated curiously.

“The ship’s captain taught Ellis a thing or two about navigation during our voyage,” Daisy explained.

“Yes, I’m sure you can see it,” Uncle Alfonso assured him.

“Perhaps Ellis and Belinda would like to find their rooms,” Daisy suggested to Rowley. “Belinda, will you please settle Ellis? Uncle and I have some things we must discuss.”

“Let me first have a word with Sir Nevis,” her uncle said, following Belinda and Ellis from the room.

Daisy stood a moment, listening to the sound of her uncle’s boots echoing down the stone hallway. When she was certain she was alone, she fell onto a settee that was still covered with a dust cloth and propped her feet on a chair. She was bone weary and wanted nothing more than to sleep in a decent bed. She closed her eyes and let her mind drift to the lake, and the hills beyond...and to the startlingly blue eyes of a Scotsman. She imagined him once again with his hands on her—this time, in that decent bed—his touch reverent, his gaze soft.

How long she was in that state, she didn’t know, but she was awakened by the sound of chuckling.

Daisy opened one eye. Her uncle was standing before her, his arms folded over his apron, smiling with amusement at her lack of decorum.

“Do you blame me?” she asked, forcing herself up with a push. “It’s been a wretched journey.”

“Yes, I suppose it has.” He walked to the sideboard and poured two glasses of wine. He returned and handed her one.

Daisy yawned, then sipped the wine. She wrinkled her nose.

Uncle Alfonso shrugged. “It was all that could be found in the fishing village.”

“This place is a shambles, Uncle,” she said morosely. “Belinda is right—it will require so much work! How will we ever put it to rights?”

Uncle Alfonso rubbed his eyes a moment. “I don’t know,” he said. He wandered with his wine to the windows and gazed out at the sun sinking behind the hills.

Daisy pushed herself to her feet and joined him there. “Can we find workers?”

“A few, I should think,” he said with a shrug. “I’ll have Sir Nevis scout about on the morrow. But it will require our concerted effort, darling.” He put his arm around her shoulders. “By that, I mean all of us.”

She smiled lopsidedly. “Are you suggesting that I indulge in labor?” she asked with mock astonishment.

“We’ll need all hands.”

Daisy kissed her uncle’s cheek, then stepped away and began to release her hair from its pins. “Belinda won’t stand for it, you know. But frankly I’d like nothing better. I’m weary of sitting about all day with nothing to occupy me but gossip and needlework.” She would not let on that she was cowed by the state of the lodge; she would keep the fears gurgling in her belly to herself.

“Shall I send for Mr. MacNally, the supposed caretaker?” he asked.

She needed to address the issue of the caretaker, quite obviously, but at the moment, all Daisy cared about was that she was exhausted, and she needed a bath, and she was desperate to free herself from these stays. “On the morrow,” she said, and mustered a smile.

She was not going to think about the shambles that surrounded her just for now. Instead she’d let thoughts of the Scotsman occupy her thoughts and would try not to look too closely at the disrepair and the foreign surroundings.

CHAPTER THREE (#uad27d6f4-5b1e-5ac5-811b-b0fac26312aa)

THE SOUND OF Fabienne’s barking brought Cailean’s head up from his task. He lived alone at Arrandale—he was almost single-handedly constructing his home—but rarely did anyone come by that was not hired on to help put up a roof or lay a floor. Today, however, he was expecting his brother Aulay—but he would be arriving by boat, up the loch. He would be bringing the wine and tea they’d recently brought in from France...without registering their cargo with the tax authorities.

All the more reason to be suspicious of whoever was now at his front door. He strode forward, grabbing up a musket on his way.

“Arrandale!” he heard someone shout as he neared the door. He pulled it open and swung the musket up onto his shoulder, sighting the man standing there.

Padraig MacNally threw his hands up and stumbled backward, almost tripping over Fabienne, whose tail was swishing madly, so pleased that someone had come to call.

“What do you want?” Cailean demanded gruffly.

MacNally began to prattle in Gaelic, something about a foreigner and the years of his life devoted to serving others with no reward for it.

With a groan of exasperation, Cailean lowered his gun. “For God’s sake, take a breath, lad. I donna understand a word of it.”

MacNally paused. He drew a deep breath. He said, in Gaelic again, “A lady has come and released me from service!” He took a cautious step forward, nervously rubbed his hand under his nose. His plaid was filthy, and from a distance of a few feet, Cailean could smell whisky on him. That was not surprising—everyone knew that the MacNallys of this glen were drunkards. “I’m without situation!”

“Aye, and whose fault is that?” Cailean sighed.

“I’ve looked after Auchenard for fourteen years!” he wailed.

“Looked after it? The place is a pile of rocks.”

“The old man refused to send money for repairs,” he insisted, seemingly on the verge of tears. “What was I to do? There was naught I could do, laird! I need your help,” he said, clasping his dirty hands together and shaking them at Cailean. “Please.”

“Aye, and what can I do, then?” Cailean asked, annoyed. MacNally was not a member of the Mackenzie clan, and he didn’t like him being here. The man could not be trusted, and Aulay would be arriving at any moment with their goods. They would store it here until they were ready to sell it. Which meant when they were certain no one was in pursuit of them for having “forgotten” to declare their cargo with the authorities.

“I tried to reason with her, but my English isn’t very good,” MacNally begged. “And she talks, laird. She talks without a breath so that a man can’t say what he might.”

Diah.

He thought of the woman he’d met on the road yesterday. The one who had looked at him as if he were a beefsteak and she a starving orphan. She’d not been at Auchenard for as much as a day and had let go the man who’d kept a watchful eye on a property all but abandoned?

That was the way of the English—or Sassenach, as they referred to them here. They seemed to appear out of the mist to take this or that, to demand change to a way of life that had been known in these hills for hundreds of years. But of all the English reavers Cailean knew, none of them were quite as striking as this one. Her eyes were shaped like those of a wily cat, the color of them as green as new pears. She had a fine figure, too—frankly, she was beautiful.

She’d been quite a surprise to him, in truth, and Cailean was not a man who was easily surprised. But with rumors swirling fast and furious about another attempt to restore a Stuart to the throne, tensions were quite high between Highlanders who disagreed about it, and between Scot and Englishman. For a beautiful English lady to suddenly appear in the Highlands was an invitation for trouble.

Aye, she was surprising and beautiful—and unforgivingly, unacceptably English. Poor MacNally was no match for them.

“Aye, then. Wait there,” Cailean said. He stepped inside, slammed the door and marched across his half-finished house toward the back to leave his brother a note.

As MacNally was on foot, they walked the mile or so to Auchenard. They came through the woods, emerging near the drive. Weeds had sprung up among the gravel, and as they neared the lodge, Cailean could see the windows were unwashed, the lawn overgrown. Cailean paused and looked pointedly at MacNally.

MacNally read his expression quite accurately. “I’ll put it to rights, laird. I will.”

Cailean grunted at that and continued on. He didn’t believe it for a moment, but MacNally was not his worry.

He strode up to the front door and rapped loudly. Several moments passed before a man wearing shirtsleeves and a leather apron answered the door. “Sir?”

“Lady Chatwick,” Cailean said.

The man blinked. He looked at MacNally, then at Cailean. “Who...who may I say is calling?” he asked uneasily.

“The laird of Arrandale.”

The man seemed shocked. He hesitated, casting a disapproving look over MacNally.

“Be quick about it, lad,” Cailean said impatiently. “I havena all day for this.”

The man’s throat bobbed with a swallow. He nodded and disappeared into the dark and dank foyer of the lodge.

Several moments passed. Cailean could hear male voices, and then a sudden and collective footfall. It sounded as if an army were advancing on the door, but there appeared only the lady, the butler and two other men. One of the men was familiar to Cailean—he’d brandished a sword yesterday. The other man was a stranger to him.

Lady Chatwick, who led them, looked worried as she approached the door, but when she saw him standing there, a peculiar thing happened. A smile lit her face so suddenly and so sunnily that it startled him. “You again,” she exclaimed, and her voice was full of...delight?

She should not be delighted to see him, and Cailean eyed her suspiciously. She was dressed plainly, her hair tied up under a cap. Her slender neck was unadorned, and he could faintly see the pulse of her heart in the hollow of her throat.

He looked away from her neck, shifted his weight onto his hip. “Aye,” he said impatiently.

Her smiled deepened. What was she doing, smiling at him like that? He didn’t like it—it unbalanced him. She should not be smiling at him; she should be trembling in her silly little boots.

“I beg your pardon,” she said, touching a wayward strand of hair. “We’ve only just arrived, as you know, and I’m afraid we’re not ready to receive callers. I had hoped to be here a week earlier, but the journey was so arduous from London that we were delayed. First the rough sea, then all these hills.”

Why was she nattering? “These hills,” he said brusquely, “is why the area is called the Highlands. One might have expected it. And I’ve no’ come to call.”

Her green eyes widened with surprise. And then she laughed, the sound of it soft and light in that cluster of men. “I thank you for not couching your opinion in poetic phrases, sir. Of course you are right—I should have expected it.”

Just then a lad pushed his way through and latched onto her skirts, staring up at Cailean with trepidation. “Ah, there you are, darling.” She turned slightly, put her hands on lad’s shoulders and moved him to stand in front of her. “May I introduce my family? My uncle, Mr. Alfonso Kimberly,” she said gesturing to the taller of the two men. “And of course, Sir Nevis you have met,” she said, her eyes twinkling with amusement.

Sir Nevis stood with his hand on the hilt of his sword. Both men glared at him with wariness, as if he were the intruder here. Cailean grunted at them. He didn’t care who they were, was not interested in introductions.

“And my son, Lord Chatwick.”

The lad stepped back into her, practically hiding in the folds of her skirt, but she gently pushed him out again. He looked to be about seven or eight years old, slight and pale, his blond hair sticking to his head. Cailean wondered if the lad was ill.

“Ellis, might you bow to the gentleman?”

The lad clasped his hands behind his back and bowed woodenly. “How do you do.”

“Latha math,” Cailean said absently.

The lad blinked up at him.

“I said, ‘Good day, lad.’ Have you no’ heard a Highlander speak?”

“I thought you might be English,” his mother said.

“English!” he very nearly bellowed. By God, he looked nothing like an Englishman! He was wearing trews, for God’s sake. “No,” he said gruffly, feeling slightly injured by the insult.

“Well, it’s not as bad as that, being English,” she chirped and gave him a lopsided little twinkle of a smile.

It was at least as bad as that. “I am a Scot,” he said stiffly.

She pulled the lad to stand in front of her again, putting her arms over his shoulders and holding him there. “You must admit you do sound a bit English,” she pointed out.

What was happening here? He’d come to speak to her about MacNally’s employment, not about the manner of his speech. As it was, MacNally was looking at him with horror. Cailean could imagine how the story would travel up and down the glen and evolve somehow into one of his being sympathetic to the English or some such nonsense. Tongues in this glen wagged with the force of gale winds. “My mother is English,” he bit out.

“Is she, indeed?” Lady Chatwick said happily. “Who is—”

“I’ve no’ come for pleasantries, madam,” he said curtly, cutting her off. “MacNally tells me you’ve released him from service.”

“Perhaps I ought to discuss this with the gentleman,” her uncle said, moving to stand beside her.

“Oh no, that’s not necessary,” she said pleasantly. “I think the gentleman means no harm.”

Of course he meant no bloody harm, but how could she possibly know what he meant? He was a dangerous man when he wanted to be, and he thought perhaps he ought to point that out...but she was talking again.

“I did indeed release Mr. MacNally from service,” she said, with a gracious incline of her head, as if she was accepting his praise. “I thought it imperative that I do so, as I explained to him. Did I not explain it, Mr. MacNally? I think we might all agree there are certain expectations when one employs another as an agent in their stead.”

MacNally looked at Cailean. “Do you see?” he asked in Gaelic. “She says so many words, and with much haste.”

Cailean ignored him. “The man has been caretaker here for nigh on fourteen years.”

“It is true that he has been employed as the caretaker here for that long...but somewhere along the way he quite forgot to take care of it.” She looked meaningfully at the broken window over her shoulder.

“I had no money,” MacNally said in Gaelic, understanding more than he was apparently willing to admit.

“He informs me your husband did no’ provide the funds for repairs, aye?”

“Did he, indeed?” she murmured, and one finely sculpted golden brow lifted above the other. “My husband has been dead for more than two years. I have not received any requests for funds to repair Auchenard, and yet I’ve seen to it that Mr. MacNally’s stipend has been sent to him with unfailing regularity.” The second delicate golden brow rose to meet the first in a direct challenge to Cailean to disagree.

That subtle challenge stirred something old and unpracticed inside Cailean. He looked away from her green eyes, glanced at MacNally and asked in Gaelic, “Is this true? You’ve not asked for the funds?”

“How was I to know to ask for funds?” he returned nervously. “No one has come round.”

Now Cailean glared down at MacNally. “Yet you’ve managed to put your hands on the stipend. Surely you know from where that has come.”

MacNally shrugged, scratched his scraggly beard and looked off contemplatively at the hills. “Did the best I could, I did,” he said defensively.

“Pardon? What does he say?” the lady asked politely.

Cailean had a sudden intuition and glared at MacNally. He asked in Gaelic, “Have you been making whisky here?”

MacNally colored.

Cailean responded with a colorful string of curse words. It was dangerous enough that he and Aulay were storing as much wine and tea as they were at Arrandale. But to have an illegal distillery on land an Englishman owned was reckless. “You’re lucky you have your fool head,” he snapped. “Off with you now. Go to Balhaire and see if there is work for you, but leave here at once before the authorities are summoned.”

At the mention of authorities, MacNally did not hesitate to stumble away.

Cailean looked at Lady Chatwick and the men behind her. She was smiling. They were not. “I beg your pardon,” he managed to say. “It appears we have bothered you unnecessarily.”

“There is no need to apologize,” she said, her eyes twinkling with delight once more. Diah, she acted as if this were all some sort of lark. He turned to go.

“My lord! May I inquire...from where did you come, exactly?”

Cailean paused. He slowly turned back to look at her and the two men behind her. Why did she ask him that? He was suspicious—after all, he was a Scot whose English grandfather had been tried for treason. He was also a man who practiced the fine art of smuggling goods into his country, outrunning British naval ships on at least a dozen occasions. He’d not put it past the English authorities to install a well-bred lady to spy, to root out the smuggling they’d failed so miserably to catch thus far. He was therefore not inclined to answer any questions posed by her.

She seemed to sense his distrust. She turned her son about and sent him into the lodge, then hopped out of the doorway and onto the flagstones. “I’m curious,” she said and leaned against a pillar that held up the portico, her fingers skirting across her décolletage, drawing his eye to the creamy skin swelling above her bodice. He slowly lifted his gaze, and she smiled. “Is it a secret?”

Was she trifling with him?

She clucked her tongue and smiled again. “It’s just that you seem unduly suspicious. I ask only because you rode away yesterday and I never expected to see you again. And yet here you are.”

“You willna see me again,” he assured her.

“No? A pity, that.”

Her smile turned sultry, and Cailean’s pulse leaped a beat or two. He was astounded by her cheek, really. He rarely met a woman so bold, and, by God, he was from Scotland—he knew more than a few bold women. “Aye, you willna. And for that you may thank your saints and pray others leave you be.”

“What others?”

Now she was being ridiculous. “Are you daft, then?” he asked disdainfully. “You shouldna be here at all.”

“Why?”

Good God, she was daft. Utterly addlepated. “Because we donna care for Sassenach here. I should think someone would have told you before you made such an arduous journey,” he drawled.

“Sassenach...” she repeated thoughtfully. “What does that mean, precisely? Does it mean ladies?” Her smile deepened into dimples. She was amusing herself.

“It means English.”

“Come in, milady,” Sir Nevis warned her. “Let him go.”

The incredibly cheeky woman ignored the man. She stood there, tracing that invisible line across the swell of porcelain skin, smooth and pale, considering Cailean.

She looked delicate. Fragile. Completely unprepared for a man like him. An appearance that belied the things that came out of her mouth. What sort of highborn woman flirted so blatantly with a stranger? What sort of woman trifled with a stranger twice her size? And yet she was not the first Englishwoman he’d known to behave in that manner, and the sudden, unwanted image of another delicate rose who’d once held his heart in her hands flooded his thoughts.

He tensed. He took a step forward. “Are you so foolish, Lady Chatwick? There is no’ a Scot in these hills who will want you and your kind here, and yet you behave as if you’re attending a garden party, aye?”

She laughed softly. “Oh, I assure you, sir—this is no garden party. There’s no garden! I am determined to have one, however, because I do find the landscape quite lovely—the scenery is unsurpassed.” Her eyes brazenly flicked over the length of him, and she grinned, saucily touching the corner of her mouth with her tongue.

That unpracticed part of him was rousing from its slumber.

“Won’t you tell me from where you came?”

Impatience and disbelief radiated hotly through him now. He had stayed longer than he’d intended, and he was not going to stand here and be interrogated by her. “Good day, madam,” he said coldly and turned about, striding away.

“Good day, sir! You must come again to Auchenard!” she called after him. “We’ll have a garden party if you like!” She laughed gaily at that.

Unbelievable.

Cailean fumed on the long walk to Arrandale, exasperated he’d been put on his heels by the Englishwoman, astounded that it had happened before he knew it, and amazed by her cheek. Och, she was barmy, that was what. And bonny. A barmy, bonny woman—the worst sort to have underfoot.

Funny how a long, hot summer could be made suddenly interesting in the space of a single day.

CHAPTER FOUR (#uad27d6f4-5b1e-5ac5-811b-b0fac26312aa)

July 28—One of the chimneys must be rebuilt, which Uncle assures me that he and Mr. Green will know how to do, but I don’t care for him to be on the roof. He has ignored me thus far and urges me to keep my thoughts to what must be done inside. My thoughts will be much crowded, then, for there are many repairs to be done. Every day we discover something new, which sends Belinda into fits of panic. I have assured her that we will manage, but I confess I spoke with far more conviction than I felt. Ellis is fearful of the deep shadows in the lodge, which cannot be avoided due to the lack of proper windows. But he is happy that he can see the night’s sky so clearly from his room and is busily charting the stars under Mr. Tuttle’s tutelage. The poor boy sneezes quite a lot, and Belinda fears the dust will make him ill. She is quite concerned there is no real village to purchase sundries and frets that she didn’t bring with her enough paints for her artwork, which she is very keen to begin when the repairs have all been made.

I know that Belinda and Ellis are not happy with the lodge, and I do so hate that I was clearly wrong to bring them to such a disagreeable place.

The Scotsman came in defense of Mr. MacNally. He does not care for me, I think it quite obvious, for he does not smile at all and did not find me the least bit humorous. His face is a lovely shade of brown, as if he has been often in the sun. It rather makes the blue of his eyes that much brighter and the plum of his lips that much darker.

I rather like it here in a strange way. It is quiet, and the landscape unmarred. I should think that it would be a lovely place to live, if one could live without society.

IT WAS TRUE that Daisy felt quite badly for having dragged her household here. She’d known the lodge was remote and had been uninhabited for a time—but she’d not been prepared for just how remote and how uninhabited. Because she hadn’t given the matter proper attention when her husband’s agent tried to explain it to her.

The truth about Auchenard was buried in the papers that he’d wanted to review with her shortly after Clive’s death. At the time, Daisy had found the discussion of a remote hunting lodge so dreadfully tedious that she could scarcely keep her eyes open. She’d been exhausted from the details of Clive’s funeral, and Scotland had seemed as far removed from her as the moon. Moreover, the estate had existed for the purpose of hunting—an activity that held no interest for her whatsoever. She had not paid the matter any heed.

Not until she had needed someplace to which to escape.

And now? More than once Daisy had considered putting her son back in the coach and returning to England, no matter how exhausted they all were.

On their first tour of the lodge, she’d been appalled by what they’d found in the lodge—a dim interior, deteriorating furnishings. And the decor! Turkeys and stag heads seemed to lurk around every corner.

“Well, then,” she’d said when they’d seen it all. “There is nothing to be done now but begin work.” She’d said it confidently, as if her occupation was that of a woman who routinely walked into deteriorating hunting lodges and rejuvenated them. “We will muster our little army and work, shall we?”

“Assuming none of us is made ill,” Belinda had said darkly from beneath the lace handkerchief she kept pressed to her nose and face.

In that moment, the prospect of defeat before Belinda was enough to spur Daisy into turning this lodge into a highland jewel.

In the days that followed, Daisy worked as hard as anyone to restore the lodge. She and her household polished and scrubbed, tore down old wall hangings, washed windows and sashes, and carted out unsuitable furnishings. Carpets were dragged outside and beaten, mattresses turned, linens placed on beds. Sir Nevis, who meant to return to England after a week, scouted the area while they worked, and returned with a craftsman to repair the windows. He also returned with information about Balhaire, the large Mackenzie estate and small village where sundries—and, thankfully, paints—could be purchased.

But as the days progressed, Ellis looked more and more disheartened. He and his tutor wandered about looking a bit lost. Ellis was curious to inspect their surroundings, but Daisy would not allow them to venture far from the lodge...the Scotsman’s warnings of others had made her a bit fearful.

She tried to engage Ellis with the lodge itself, but the boy, like any nine-year-old, did not want to beat carpets. So Daisy urged him to continue his star charting. That occupied him until they had charted all that they could. She then commanded him to help her clean windows, but he tired easily.

When Daisy wasn’t struggling to please her son, she toiled from morning to sundown in a manner she’d never experienced in her life.

At first Rowley, Uncle Alfonso and Belinda had tried to dissuade her from it. Great ladies did not beat carpets, they said. Great ladies did not scrub floors. But Daisy ignored their protests—she found the work oddly soothing. There were too many thoughts that plagued her when she was left idle, such as whom she’d be forced to marry, and how the days of her freedom were relentlessly ticking away. Whether or not Rob would reach her in time, what was wrong with her son that he was so fragile, and how cake-headed she’d been to think a journey to the northern part of Scotland could possibly be a good idea, and, of course, what a terrible thing she’d done, dragging her family here.

Yes, she preferred the labor to her thoughts. At the end of each day, she ached with the physical exertion, but the ache was not unpleasant.

But there were times, when she couldn’t keep her thoughts from her head, that Daisy felt a gnawing anger with her late husband. Clive had forced her into this untenable situation, and her feelings about it had not changed with time. She felt betrayed by the man she had respected and revered and tried to love. She’d been a dutiful wife—how could he have had so little regard for her? How could he believe she would jeopardize her own son’s future for her own pleasure?

Sadly, the answers to these questions were buried with Clive.

By the end of their first fortnight at Auchenard, Daisy could see that the old lodge was beginning to emerge, and she was proud of the work they’d done. She began to notice less the repairs that had yet to be made and more of the vistas that surrounded the lodge. It was possible to gaze out at the lake and the hills beyond and forget her worries.

When she was satisfied with the work on the interior, Daisy turned her attention to the garden. Or what she assumed had been a garden at some point. Whatever it might have been, it was overgrown. Vines as thick as her arm crawled up walls and a fountain, and weeds had invaded what surely once had been a manicured lawn. She’d donned a leather apron and old straw hat she’d found in the stables. She’d cut vines and pulled weeds until her hands were rough. She crawled into bed at the end of those days and slept like the dead.

Belinda complained that the sun was freckling her skin and turning her color. Daisy didn’t care.

Each morning she rose with the dawn light, pulled a shawl around her shoulders and sat at the bank of windows that overlooked the lake from the master bedchamber. She’d open them to the cool morning mist, withdraw her diary from a drawer in the desk and make note of the previous day.

She pressed flowers into the book, as well as the leaves of a tree she’d never seen before, and had sketched the tree beside it. She’d drawn pictures of boats sliding by on the lake, of a red stag she saw one morning standing just beyond the walls, staring at the lodge.

Yesterday, Daisy had uncovered an arch in the stone wall that bordered the garden. She dipped her quill into the inkwell to record it—but a movement outside her window caught her eye.

The mist was settling in over the top of the garden, yet she could plainly see a dog sniffing about in a space she’d cleared. Not just any dog, either—it was enormous, at least twice as tall as any dog she’d ever seen, with wiry, coarse fur. She wondered if it was wild. She stood up, pulled her Kashmir shawl tightly around her and leaned across the desk to have a better look. “Where did you come from?” she murmured.

The dog put its snout to the ground and inched toward the one rosebush she’d managed to save.

Daisy hurried out of her room, down the stairs and the wide corridor that led to the great room and outside.

When she reached the garden, she slowed, tiptoeing through the gate, her bare feet on cool, wet earth that slipped in between her toes.

The dog’s head snapped up as Daisy moved deeper into the garden. It lifted its snout in the air, nostrils working to catch her scent. Daisy froze. The dog didn’t seem afraid of her, only curious.

She took another step, and the dog crouched down, as if it meant to flee. “Don’t go,” she whispered, slowly squatting down and holding out her hand. “Come.”

The dog stood alert, its tail high, watching her warily.

She looked around for something to entice it. There was nothing but a battered rose, and she reached for it, breaking it off at the stem and wincing when a thorn pierced her thumb. She crushed the petals in her hand and held them out. “Come,” she said again.