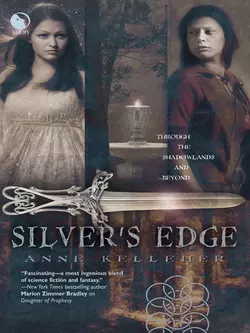

Silver′s Edge

Anne Kelleher

THROUGH THE SHADOWLANDS: Where the touch of silver was Protection, Power and Peril… UNWILLINGLY ENTWINED… There is more danger than usual in the Otherworld of the Sidhe and the mortal world of the Shadowlands. An unlikely group of conspirators–both mortal and Sidhe–plot to overthrow both thrones. They'd stolen the silver caul that protected the borders between the realms–and set into motion a perilous war….A BLACKSMITH'S DAUGHTER, A SIDHE LADY, A MORTAL QUEENThree women stand against the encroaching evil. All they have is a girl's love for her father, a lady's for her queen–and a queen's for her country. Nessa, Delphinea and Cecily are each driven by a personal destiny, yet share a fierce sense of love, justice and determination to protect what is theirs.Will the spirit and strength of these women be enough to turn back the tide of the goblin hordes waiting to overrun the kingdoms? Perhaps. But the battle must still be fought….

Praise for

ANNE KELLEHER

“I found it one of those books which keeps one’s eyes glued to the page…an outstanding piece of work.”

—Andre Norton on Daughter of Prophecy

“…displays vivid imagination.”

—Publishers Weekly

“…engaging and powerful.”

—Voya on The Misbegotten King

“Fascinating—a most ingenious blend of science fiction and fantasy.”

—New York Times bestselling author Marion Zimmer Bradley on Daughter of Prophecy

SILVER’S EDGE

ANNE KELLEHER

This book is dedicated, with love,

to my son Jamie, my intrepid little adventurer—

may you always believe that tall buildings

are made to be leaped with a single bound.

Glossary of People and Places

Faerie—the sidhe word for their own world. It includes the Wastelands

The Shadowlands—the sidhe word for the mortal world

The Wastelands—that part of Faerie to which the goblins have been banished

Lyonesse—legendary lost land that is said to have lain to the east of Faerie

Brynhyvar—the country that, in the mortal world, overlaps with Faerie

The Otherworld—the mortal name for Faerie

TirNa’lugh—the lands of light; the shining lands—mortal name for Faerie; becoming archaic

The Summerlands—place where mortals go at death

Humbria—mortal country across the Murhevnian Sea to the east of Brynhyvar

Lacquilea—mortal country lying to the south of Brynhyvar

Killcairn—Nessa’s village

Killcrag—neighboring village to the south

Killcarrick—lake and the keep

Alemandine—Queen of sidhe

Xerruw—Goblin King

Vinaver—Alemandine’s younger twin sister and the rightful Queen

Artimour—Alemandine’s half-mortal half brother

Gloriana—mother of Vinaver, Alemandine and Artimour

Timias—Gloriana’s chief councilor and the unacknowledged father of Alemandine and Vinaver

Eponea—Mistress of the Queen’s Horses

Delphinea—Eponea’s daughter

Finuviel—Vinaver’s son by the god Herne; rightful King of Faerie

Hudibras—Alemandine’s consort

Gorlias, Philomemnon, Berillian—councilors to the Queen

Petri—Delphinea’s servant gremlin

Khouri—leader of the gremlin revolt and plot to steal the Caul

Nessa—nineteen-year-old daughter of Dougal, the blacksmith of Killcairn

Dougal—Nessa’s father; Essa’s husband; stolen into Faerie by Vinaver

Griffin—Dougal’s eighteen-year-old apprentice

Donnor, Duke of Gar—overlord of Killcairn and surrounding country; uncle of the mad King and leader of the rebellion against him

Cadwyr, Duke of Allovale—Donnor’s nephew and heir

Cecily of Mochmorna—Donnor’s wife; heiress to the throne of Brynhyvar

Kian of Garn—Donnor’s First Knight

Hoell—mad King of Brynhyvar

Merle—Queen of Brynhyvar; princess of Humbria

Renvahr, Duke of Longborth—brother of Queen Merle; elected Protector of the Realm of Brynhyvar

Granny Wren—wicce woman of Killcairn

Granny Molly—wicce woman of Killcrag

Engus—blacksmith of Killcarrick

Uwen—Kian’s second in command

The Hag—immortal who dwells in the rocks and caves below Faerie; the moonstone globe was stolen from her when the Caul was forged

Herne—immortal who dwells within the Faerie forests, from which he rides out on Samhain night, leading the Wild Hunt across the worlds

Great Mother—mortal name for the Hag

The Horned One—mortal name for Herne

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Nothing I have ever written has not owed a great deal to the people who have to put up with me while I write. Thanks go to my agent, Jennifer Jackson, who lit a candle just as the lights were going out; to Patrice Fitzgerald, Olivia Lawrence, Robert Becerra and Laura Sebastian-Coleman, who gave me feedback and wonderful suggestions; to Anne Sheridan, who proofread the final draft—any mistakes are mine; to Laura at The Purple Rose and Bobbi at Maggie Dailey’s for providing tea and source material; to Loreena McKennitt, Julee Glaub and Bruce Springsteen, whose music made me see the OtherWorld; to GTimeJoe, who kept my head in the clouds; to the folks in the CT Over 40 chat room on AOL for being so unflaggingly supportive even when I was at my most cranky; to the wonderful members of the FMC for cheerleading; to my darling daughters, Kate, Meg and Libby, who bore the brunt of dishes, laundry and trash; and finally, to Donny. You made it all possible.

Contents

PROLOGUE

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

EPILOGUE

An Interview with Anne Kelleher

PROLOGUE

Then

Down dusty roads the child fled, heart drumming in her thin chest like the gallop of a thousand horses, chased from sleep by hulking hordes of goblins who grabbed at her with gleaming teeth and outstretched claws. She startled awake, the echoes of her dream screams dying in her ears, crying aloud at the sight of the banked grate, where the coals glowed like red eyes in the dark room. A cold wind was howling in the trees, and the window rattled in its frame. A gusty draft stirred the curtains just as something crashed onto the roof above her head. She cried again, louder now, and yanked her thick woolen blanket higher, the rest of her small body stiffening with dread, the whole house, it seemed, shuddering under the impact.

“Nessie? You all right?” Her father’s broad face loomed out of the shadows of the doorway, his white nightshirt luminous in the gray light. He came closer, feet bare, the black hair on his chest curling out of the open collar of his nightshirt. A dark haze of beard shadowed his chin. Disheveled and bleary-eyed as he was, the sight of him relaxed her instantly, even as the sound of something scraping against the windowpane made her eyes widen once more.

“Papa, the goblins,” she moaned. “They’re chasing me—there’s one outside my window—”

“Hush, now.” His voice was a gravelly rumble as compelling as distant thunder. “That’s nothing but the branch I should’ve had the sense to cut down long before this. The wind brought it down, that’s all. There’re no goblins outside, not now, not ever.”

Cautiously the child peered over the homespun sheet, which was soft with many washings. Her father had spoken, her father who was the rock at the center of her world. Her father was Dougal the village blacksmith and the best armorer for leagues around. Even the mighty Duke of Gar came to Dougal when he wanted a new sword or dagger. “But, Papa,” she whispered, “Granny Wren, tonight, at the Gathering, she said the goblins come a-hunting little children—little children is what they like best to eat.”

With a stifled hiss of exasperation, the blacksmith crossed the small space to his daughter’s bed and knelt on the ragged scrap of rug. “Ah, little one, Granny Wren likes to hear herself talk. It’s how she knows she’s still alive, I think, for there’s no other reason for half the things she says. But come now, didn’t you also hear her speak of Bran? Bran Brownbeard, the greatest smith there ever was, in either Brynhyvar or the OtherWorld, the place called TirNa’lugh?” He paused. Her dark eyes were bright in her rosy little face and she shook her head, falling readily into the spell his whisper wove. “Perhaps you’d already gone to sleep by then? Hmm? Such a tired little girl I carried home tonight.” He smiled and smoothed the dark, damp curls off her forehead, his thick slab of a hand bigger than her entire face. “Bran Brownbeard was a mighty mortal man, who with the help of the Queen of the sidhe and her magic, forged the Silver Caul that lies upon the moonstone globe in the great palace in the very heart of the Other World.”

“What’s a call, Papa?”

“A caul, sweetling. It’s like—like a net, or loosely woven blanket, made of purest silver.”

“How’d he do that, Papa?”

“He took silver, for silver hurts the goblin, and the sidhe, too, more than anything else—it burns them and that’s why a mortal man was needed to do it—and with the sidhe Queen of the OtherWorld, who hates the Goblin King, for he would take her kingdom if he could, together they worked great magic and made a powerful web of finest strands of purest silver. They called it the Silver Caul, and the Queen took it to her palace, and there she placed it over a great green moonstone, and there it lies to this very day, keeping the goblins out of Brynhyvar.”

“Why does silver hurt the goblins?”

“I don’t know rightly, sweetling. But it’s why we wear these—” He fumbled at the neck of his nightshirt and dangled his silver amulet on its leather cord before her.

“That’s why we must never take it off?”

“Exactly. The silver protects us.”

“But, Papa, if the Silver Caul keeps the goblins out, why must we wear silver, too?”

Because there are worse things than goblins, he nearly replied. It was the race that called themselves the sidhe that were the worst of all, for they seduced mortals with promises of otherworldly delight, leading them to vanish out of sight and time. Your own mother was snared by one of them, he almost said, but he caught himself. They were treading dangerously close to questions for which he must carefully consider the replies. He pushed aside the curtain and peered out into the night. It was coming up to dawn. The low-lying clouds overlay a sky of lighter gray. Time to stir the oats he’d set to cook last night in the great iron kettle nestled in the warm forge, to check for damage left by the now-passing storm, to try to decide what to tell the child if her questions led them to the subject of her mother, and if she were old enough to know even part of the truth. “Not now, sweetheart. I’ll tell you the story later. I promise. But ’tis so late, it’s early, and I must be about my work. You go back to sleep for a bit, it’s too cold to be running about early today.” He kissed each one of her grubby little fingers in turn, noticing how pink they were beneath a thin layer of grime, then rose to go. He resolved to remember to drag the bathtub from the shed beside the kitchen before nightfall. Her eyelids were already beginning to droop.

“But, Papa?” Her voice stopped him at the door. “The Silver Caul? That’s what keeps the goblins away? For real?”

“There are no goblins in Brynhyvar, Nessa. I promise. So back to sleep with you, now, like a good girl.”

“Yes, Papa.” She shut her eyes with a sigh.

He ducked his head beneath the uneven frame of the low doorway and paused to look over his shoulder at the little face lying on the pillow. Dearer to him than all he owned, dearer than life, she was. He had lost her mother to the sidhe, and he was determined such a fate should never befall her daughter. Such a headstrong little thing, she could be, so like her mother, curious and engaging. But if she seemed more interested in the fire and the forge, hammer and tongs, than in the tools of more womanly pursuits, so much the better. Better her mind be full of iron, he thought, than the sort of empty-headed nonsense which had contributed to her mother’s disappearance.

The child curled on her side, one round cheek pillowed on her open palm, a scrap of threadbare blanket nestled beneath her chin. A line from an ancient lullaby ran through his head. The might of Bran protects thee, the Faerie Queen shall bless thee, no goblin claw will rend thee. But he took no comfort in it, for he expected no blessing from that quarter. He would see to it that if ever goblin or sidhe touched so much as a hair of his daughter’s head, she would be well-prepared to defend herself.

1

Now

The fat spider leapt lightly along the serrated edges of the stone spikes which rose like a lizard’s spine along the high back of the throne of the Goblin King. It scampered across the rough stone, anchored from above by a nearly invisible filament, darting just inches from the leathery maw of Xerruw, the Goblin King, who leaned upon one elbow and watched it with detached interest. So easily he could flick it into oblivion with a snap of his tongue. Its legs waved frantically as it manipulated the gossamer strands, as if it sensed a predator. But, though he watched it with a hungry intent, Xerruw’s mind was not bent on food. Spin, little spider. You have reminded me of the value of a trap.

A smoky fire burned fitfully in the stone pit in the center of the cavernous hall, and a dull gray light filtered through the arrow slits set within the soaring arches of its central tower. A cold draft whined down from the upper reaches, but Xerruw, if he noticed the chill at all, gave no sign. He sprawled across his massive throne, which had been carved out of a boulder bigger than the huts of men, in that last happy age when the goblins reigned supreme and the sidhe cowered beneath the banks of rivers and glens, hiding in the noon, hunted at night like luminous fish flitting through the dark depths of the primeval forests. Those were the days of glory, he reflected, as he picked his teeth with the fingerbone of a human child.

It was an ancient fingerbone, worn sliver-fine from long years of gnawing—they’d not been fortunate to find a child roaming in these lands for more time than he’d care to remember—but he liked to fancy that it retained a hint of the sweet flavor of young man-meat, enough to envision a time still to come when, free of the fetters of sidhe magic, his kind could hunt both the human herd and the sidhe at will. So he watched the spider, sucking on his bone, while in the niches carved into the rock beneath his seat, three hags muttered among themselves as they crouched restlessly on their nests of lumpy eggs, ceaselessly complaining of the lack of meat.

His gray eyes were nearly closed, and he appeared lost in thought, his attention wholly focused on the spider, but he knew that three of the six guards dicing opposite the hags were cheating on the others, and that the goblins sharpening their weapons closest by the door mumbled mutiny. Let them, he mused, enjoying the worn smoothness of the bone against his teeth. Long years he’d sat, brooding on his throne, biding his time, plotting his strategy, awaiting the very news he’d received yesterday.

For the sidhe Queen was in whelp—the sidhe witch who dared to style herself Queen of all Faerie. It was only a matter of time now, and her power would falter, her magic naturally diminish as the birth approached, giving him at last an opening, a foothold, a chance to once again claim all of Faerie for his own. In the past weeks, he had begun to sense it—a subtle but unmistakable weakening in the complex webs of power which held the border of the Wastelands, where her forces had driven his kind after the last war. And this time, they would attack—not just with blades and spears, arrows and bolts, the weapons of sheer brute force. No, this time he would try something worthy of a sidhe’s own cunning. He would succeed where the others of his kind had failed, catching the complacent sidhe off guard when they were most critically vulnerable. Like the spider, he mused. And like the spider, he would weave his own trap and wait.

A chill draft suddenly blasted through the hall, and the hags screeched and cackled, rocking back and forth on their haunches to protect their eggs. The blast of air was accompanied by a thunderous boom—the sound of the inner gates closing. The scouting party had returned. But even as he was about to shift positions and settle more comfortably to await their report, Xerruw bolted upright, for he caught, just beneath the acrid smoke of the fire, a scent, at once coppery and sweet, earthy and sour, threading like a strand of yarn through the smooth texture of the air. He snarled in the direction of the hags, and rose to his feet as Iruk, the Captain of his Goblin Guard, strode in, his fellows jogging behind him, a blur of dull gray limbs and black metal in unison. The guards stopped gaming and sharpening, and looked up, sniffing expectantly. Then the hags caught the scent and their keening cries of pleasure erupted in a hungry harmony. A snarl and another hard glare silenced them, but they licked their lips and stared back at him with eager eyes.

“What is this you bring?” he asked suspiciously, for the unmistakable aroma of man was in the air, and he knew already what lay within the hide-bound burden Iruk bore across his shoulders.

“Great Xerruw.” Iruk circled around the fire pit, stopping at the very base of the throne. He glanced at the hags, who squatted over their nests, crooning softly, as though he half expected them to leap at him. He knelt, staggering a little beneath the weight of his burden, then bent his neck and let it roll to the first step of the throne. He pulled away the hide and the still body of a human male sprawled at the base of Xerruw’s throne, fresh blood congealing on his skull and at his throat.

Xerruw stared down at the offering. His nostrils quivered and saliva flooded his mouth. But even as a ravenous hunger swelled from the pit of his belly, making it nearly impossible not to rip off the closest limb, misgiving made him raise his head and scan the faces of the guards who stared back at him with unabashed glee. Saliva ran down their jaws, and their maws quivered, nostrils flaring. The last time they’d tasted human meat was countless ages past. It was a testimony to their allegiance to him that they’d returned the carcass intact. One of them was missing.

He looked down at the dead human. It had been a big male, dark and hairy, with burly arms and massive shoulders. Strong on him, beneath the scent of blood and flesh and sweat and urine, hung the smell of smoke and burning metal. His face and beard were damp and he was nearly naked except for linen breeches and the amulet he wore around his neck. In the unsteady light, it shone with a clear, soft gleam. Xerruw’s lip curled and his eyes narrowed at the sight. “Silver,” he muttered. “This should not be.” Silver was anathema to sidhe and to goblin, humankind’s only sure defense against goblin teeth and sidhe magic. “I like this not,” he said at last, shaking his heavy head. “Where did you find it?”

“By the lake. Upon the farthest shore. He did not know he’d slid across the border. We took him unawares.” Iruk dragged one claw through the gelatinous clot on the human’s neck, and held it out to Xerruw. The scent of the fresh kill exploded like fire through Xerruw’s veins and he licked his lips without thinking.

“Do you not see the silver?” Xerruw gestured down.

Iruk shrugged. “Base metal, most like. We carried him here well-wrapped—there was no problem.” He threw the clot at his lord’s feet, and gazed up at him expectantly, awaiting some sign of acceptance of the kill. Xerruw squatted down, coiling his tail beneath his haunches, sniffing suspiciously. Iruk was probably right. The amulet must indeed contain a fair portion of base metal. He examined the clothing the human wore. The linen was coarse, the heavily muscled body bore testimony to a lifetime of hard labor. But the hide they’d used to wrap the human in was slightly singed where the amulet had rested, and above it, he could feel a tingle emanating from it, a shimmer in the air. It had potency, enough, then. The amulet must be cast into the deepest part of the lake, where he instinctively knew the dark waters would neutralize its corrosive effect. He pulled his dagger from his sheath and cut the leather cord around the neck. He held the amulet out to Iruk by the cord.

Iruk stepped back with a hiss.

“Throw this in the lake whence it came.” He pushed it closer to Iruk’s face.

Iruk hissed again as the amulet swung near his jaw, jerking his head well out of reach.

“So maybe this metal is not so base, my Captain?”

“So maybe this is not so much mortal meat, my lord. Shall I throw it in the lake, too?”

“Where is Bukai?”

Their eyes collided in a challenge, as a low growl of impatience rolled through the growing crowd.

“He fell beneath the water. The mortal killed him.”

Xerruw snarled, low in his throat, and shook the amulet. “Take it.” With a growl, Iruk grabbed it by the cord and dropped it into a pouch he wore at his waist. It made a slight hiss as the troll-hide closed around it. Xerruw smiled grimly. He bent and ripped a single ear off the mortal with a languid wave of his claw, and, holding it high, shook it, then crammed it into his mouth for all to see. He ripped the other ear off and tossed it to Iruk. “Get that thing out of here now,” he spat out through the mouthful of flesh and blood and gristle.

Iruk nodded, satisfied, turned on his heel and stalked from the hall.

A cheer erupted from the doorways, where the inhabitants of his castle were creeping forward from their dens, drawn by the seductive scent. The hags exploded into gleeful shrieks, and the rest of the scouting party raised their arms and leapt over the fire pit, tails whipping high, joining the dance. Ogres and goblins bellowed, and more hags rushed from the cellars below to prepare the feast. He reached down, and dragged one long claw through the gelatinous clot, which oozed a metallic-smelling steam, and licked the blood slowly, thoughtfully, while his court capered and pranced around him.

The silver’s clear gleam troubled him, the apparent ease with which the human had slipped into Faerie troubled him. He stared down at the hide, where the silver had left a deep mark. Amid the general rejoicing, he felt wary, suspicious. He unfolded his long frame and settled down into his throne, where the spider rested in the middle of a meticulous web. What could account for the presence of silver in Faerie?

The spider scampered higher, as the cacophony rose. Xerruw put the fragile fingerbone in his mouth once more, and crunched down harder than he intended. At once, it snapped into a shower of shards, dissolving into dust on his tongue. He gazed at the stub remaining between his fingertips. There were more goblins now, soldiers from the barracks, hags from the innermost recesses of the keep, capering around the fire pit, leaping high over the flames. Let his people dance. Perhaps this human was a sign—a sign that soon all of Faerie would be his. His mind reeled, as instinct overwhelmed reason. The sweet human scent was sweeping him away into an ecstasy of expectation. He looked around the crowded hall, and forgot the puzzle of the silver amulet, forgot the sidhe witch Queen, forgot everything but the ripe rich aroma that thickened around his head like fog. The bloodlust surged through his veins like a burst dam.

We must grow strong. We must all grow strong. And we will grow strong. He rose to his full height and joined in the rising chorus with a roar. “We will all grow strong on human meat!”

2

“I’m going and you can’t stop me.” The flicker of the lone lantern caused shadows to quiver across Nessa’s face, but the expression in her dark eyes was one of steady purpose.

Griffin closed his own against thumb and forefinger, rubbing away the dry grit of exhaustion. The fat candle within the lantern hissed and spat a gob of tallow. It landed with a sizzle on the dead goblin, which lay between them, slack-faced and limp-limbed, on the straw-strewn dirt of the lean-to next to Farmer Breslin’s barn. The stink of singed hair mingled with the putrid odor already rising from the corpse, and Griffin had to swallow hard against a wave of nausea. “It’s madness and I can’t let you. Your father would kill me—”

“Not if I kill you first.” She gave him one hard look, shot from under full brows which arched in a feminine replica of her father’s own, then looked down at the corpse, assessed it as dispassionately as she might a lump of ore, then shifted to a more comfortable squat beside the body.

The villagers’ decision to place the body in the sty had less to do with proximity or place than concern for the fact that all animals downwind of it within a certain radius whimpered and pulled on their tethers, or pushed against whatever confined them, and it was hoped that the odor might be masked somewhat by the smell emanating from the sty. But the earthy aroma of the pigs was like perfume compared to the reeking miasma which clogged Griffin’s nose. He steeled himself against the stench, and leaned over the body, his voice a husky whisper. “What if you can’t find him? What if you can’t get back? What if everyone thinks you’re mad when you return and won’t have anything to do with you? Why can’t you just wait for the Duke’s men?”

In spite of her obvious resolve, Nessa grimaced as she gingerly touched the clammy flesh which hung slack on the goblin’s face, and this time, the look she shot him was one of utter disdain. “What do I care what they think? Those old biddies do nothing but whisper about me, but they were all quick to rush to the house tonight, weren’t they? Bothersome hens—it was just a chance to poke their noses into the pantry and the kitchen and the bedrooms and make nasty comments about you and me. They don’t care about Papa, they care about sticking their faces in other people’s troubles—not so they can do anything, but so they can talk about it. And the Duke just raised his standard against the King. How much time do you think he’ll spare a missing smith?”

“I should think he’ll make time for a dead goblin. If he doesn’t come himself, you know he’ll send some—”

“Maybe, eventually. But by that time, it may be too late. My father could be dead. Or lost forever, like my mother.” Her mouth hardened and she reached into the leather sack for the small ax.

“What are you doing, Nessa?” Griffin stared at her in horrified disbelief. These last few hours were like a long bad dream that refused to end. It had started when Jemmy, the herder’s boy, had run up from the lake shouting that a goblin lay floating in the water.

The village had reacted as one body, men and women and children, all running pell-mell to the sandy shore, where the thick, hide-clad corpse bumped up against the traps set just at knee depth. The men had waded in, dragging it away from the traps with branches, teasing it ashore. A general gasp had arisen when they’d turned the body over, and the stuff of nightmare and legend lay revealed. Long rows of serrated, jagged teeth in a wide leathery maw, slitted eyes and ears like bat wings, and a hard, leathery hide that ended at each hand in three-inch claws. A jagged wound, curiously singed around the edges, disgorged the contents of its entrails, purplish and glistening with foul-smelling slime.

It was decided that despite the lateness of the hour—the last rays of the sun had long since been swallowed up by shadows—a messenger must be sent to Killcarrick Keep, where it was hoped that the Sheriff, if not the Duke himself, would be in residence. It was during the discussion as to who should go that Nessa had raised her clear voice in one anxious question. “Where’s my father?”

But Dougal, who had left the smithy much earlier that afternoon than was his custom, ostensibly to check the very traps that his apprentice, Griffin, had set just that morning, was nowhere to be found. Despite their usual censure, a flock of clucking women descended on Nessa, while the men patted Griffin’s back and muttered encouragement. He’d been left standing at the smithy gate, while the tide of women swept past, bearing Nessa inside in a swirl of skirts and a flutter of shawls, watching it all with a growing sense of foreboding. It was common knowledge that Nessa’s own mother had been swept into the OtherWorld, carried away by a knight of the sidhe who’d induced her to remove her silver, and Nessa had always been regarded as slightly touched, slightly tainted, as if she had possibly inherited some susceptibility they did not want to share. Dougal’s unorthodox method of raising his daughter had drawn harsh criticism, too, for while the goodwives of the village were inclined to be sympathetic to the motherless girl, they strongly disapproved of the freedom he allowed her, the smithing he’d taught her. Each of them had approached the blacksmith about taking the girl under a wing; all of them had been rebuffed. Dougal was above noticing most of it, but these last few years had been hard on Nessa. Griffin had watched her bear it, with the same sort of silence as she watched them argue that there was only a coincidental connection between the goblin and the smith’s disappearance, since there was no sign of Dougal’s amulet.

But Griffin could well imagine the emotions swirling behind Nessa’s shadowed eyes. At nineteen, she was part sister, part rival, part secret love. She adored her father—that had been clear to him from the very beginning, when he’d joined the household as a twelve-year-old apprentice when she was barely ten—and endured the growing distance between herself and the other villagers stoically. In a world without Dougal, Griffin wondered what would become of Nessa. Under Dougal’s tutelage, she had gained much proficiency as a smith, and was, to Griffin’s mortification, his equal in skill if not in strength. The smithy would of course be hers, someday, on Dougal’s death. But was she truly equipped to make her way in the world, he wondered, as he shooed a gaggle of curious giggling girls from her tiny bedroom. She was so different from all the other girls, possessing only what knowledge of housekeeping as Dougal had—what villager would marry her? And how many of Dougal’s customers would frequent a female blacksmith? She would need a man to handle the heavier jobs. That thought gave him a grim satisfaction, for he had fallen in love with Nessa years ago. But now was not the time to think of any possible future. Here was an opportunity at last to show how much he cared for her. And so he hung back, hovering, watching, listening, wondering how best to help, turning the possibilities over in his mind.

The day had begun badly, for something was clearly weighing upon Dougal from the moment he got up. At breakfast, Nessa asked her father who the two visitors were late last night, two visitors Griffin hadn’t even heard come in. Dougal replied with the same hard look as the one with which she’d just answered Griffin. At Griffin’s first opportunity, as he was putting the breakfast dishes to soak, and Nessa was hauling in a sack of coal for the fire, he asked her, “What visitors? When?”

“Last night—long after you were snoring. If you hadn’t been so quick abed you’d have heard them, too.” She answered him in a quick whisper, for Dougal had said little at breakfast. His eyes were hooded, his mouth grim.

“I hauled ore all day,” he protested. “Did you get a look at them? How long were they here?”

“Not long. Papa knew one of them, for I heard him cry ‘You!’ Then they lowered their voices, and spoke a while but I couldn’t hear what they were saying underneath your snores. Then they left—and I heard him working, long into the night.”

“What was he mak—” he started to ask, but Dougal bellowed for the coal, and Nessa hefted her burden. There was no further opportunity to ask more, and when Dougal left the smithy, earlier than normal, muttering about the traps, they had watched him uncover a narrow bundle wrapped in cloth from beneath a pile of gear, and looked at each other with questioning eyes. “That’s what he was making last night,” Griffin had said, as the smith disappeared down the lane in the direction of the lake. “Let’s follow him, and see where he goes with that.”

“Let’s not,” said Nessa, smarting under the rough side of her father’s tongue, for his mood had been dark all day. Griffin could only imagine what she thought about that now. If only they’d followed, they might have a better idea of Dougal’s fate.

As the dinner hour approached, Griffin had laid down his tools, expecting to go down the lane to pick up the evening loaves from the herder’s wife, Mara, whom Dougal paid to bake, since Nessa didn’t know how. It was yet another reason the goodwives whispered, and a chore Griffin assumed to spare her their sometimes ill-tempered comments. But then Jemmy had come charging down the lane, heralding the news about the goblin, and the bread was forgotten, along with everything else, save Dougal.

As the night lengthened, Griffin stayed on the periphery of the activity, fetching wood and water as required, watching over Nessa from afar. She sat at the rough kitchen table, stone-faced and calm, accepting a knocker-full of hard corn whiskey, tossing it back with such ease even Griffin was astonished. Out of Nessa’s hearing, the women argued amongst themselves in lowered voices, alternatively scolding and silencing each other until Griffin wondered how Nessa could sit with such silent dignity. When the last of them had finally departed, it was well after midnight. But instead of going to her bed, she had risen to her feet and rolled her shoulders back in the same stretch with which she approached fire and forge, and reached for the small ax which hung beside the door.

“What are you doing?” he’d asked, puzzled by her obvious purpose. The fire illuminated her tunic. The stains of the day were lost in the play of shadow and the homespun fabric was pinkish in the red light. Her skin was rosy from the fire, color high on her cheekbones, her dark eyes focused with such calm determination, that, as she turned to face him, holding the ax, he was momentarily afraid of her. She looked like the Marrihugh, the warrior goddess, standing there beside the fire, her bare arms round with defined muscle, forearms corded with veins, fingertips still black with soot. Her shoulders were broad, her back was straight. She was not as tall as her father, but she was strong from a girlhood spent hammering molten metal over an anvil. “What are you doing, Nessa?”

“I’m going to find him,” she replied, in the same matter-of-fact tone she might’ve answered a customer.

“At this hour? The woods were searched—where do you mean to look?”

“I’m going into the OtherWorld, into TirNa’lugh. It’ll soon be dawn, and that’s the best time.”

He’d reached across the space that separated them, and grabbed her arm. “Nessie, that’s madness.”

They were just about the same height and she stared back at him, shaking off his arm. “Where else to look? The goblin appears, my father is missing. What else to think but that they are connected? Why else would my father just go off?”

Griffin stared at her, his mind a mad whirl. “Nessie, please—” How to say gently that Dougal might lay dead beneath the water? Dead within the forest? If Dougal had indeed killed the goblin, wasn’t it possible that the goblin had killed him? “Be reasonable. There’s nothing to prove he’s gone into the OtherWorld. What if he’s just lying somewhere—hurt or…even dead?” He whispered the last.

“I won’t believe that.” She lifted her chin in a challenge, her eyes hard nuggets of iron in her flushed face. He had stared at her as she dropped the ax into a leather sack, buckled her dagger around her waist, and wrapped her cloak over her shoulders. Then she slung the sack over her shoulder. “Not one of them—” she dismissed the whole village with a jerk of her head over her shoulder “—would dream of looking for him in the OtherWorld, and it will take an order from the Duke before anyone else dares.” Without another word, she left the house.

He scampered after her, up the hill, in the direction of Farmer Breslin’s sty. She had not replied to any other questions, nor even spoken until just now, when they were kneeling on either side of the goblin. He bit his lip, trying to think of something to say that would convince her to stay, but he knew her in this mood. Arguing was useless. She gripped the goblin’s matted hair and tugged, but the body had hardened into rigor and the head wouldn’t budge. “Then I’ll come with you.”

She rocked back on her heels, regarding him with surprised gratitude. “I know you’d come with me if I asked you to. According to the stories, if I’m alone I’ll have a better chance of getting across the border and into the OtherWorld.”

“And a better chance of getting out if we’re together. What if you run into something like this?” He gestured at the goblin.

“It’s at dusk the goblins hunt.”

“How can you believe the old stories?”

“You mean you can look on this and not?”

He shook his head, mind reeling with frustration and fatigue. “Of course I believe, we all believe now, I suppose. But how do you know the legends are right about everything? What if some of them are wrong? And what if you stumble into a nest of…of these?”

“I can take care of myself.” She patted the dagger which lay in the curve of her waist like a lover’s hand.

“Nessa, will you listen to me? This is madness. You must be moonmazed already if you think you can actually get into the OtherWorld and come back, let alone bring your father back, if that’s truly where he is. I—I mean, the OtherWorld is a big place. Where do you intend to look?”

“I’m going to the Queen, and I’m showing her the goblin’s head. Goblins shouldn’t even be able to get into Brynhyvar. Haven’t you ever heard of Bran Brownbeard?”

“Of course I have but maybe not every story’s true. Don’t you think you should at least talk to Granny Wren?”

“Granny Wren?” Her skeptical tone was a perfect echo of Dougal’s, an octave or so higher.

“She’s a wicce-woman, Nessa, surely you should talk to her before you go—”

“What’s corn magic got to do with goblins? There’s more to this than either of us understand, Griffin. Those visitors last night—the ones who came in so late? Papa recognized one of them, but the other was a sidhe. I saw the eyes when he drew back his hood, just as Papa ordered me back to bed. You think it’s coincidence that one of them comes to the forge late last night, when all decent folk are long abed, and then a dead goblin washes ashore upon our very lake? The same time as Papa disappears? Well, I don’t. For all I know, or you know, or anyone else for that matter, this was all part of some trap to snatch him into the OtherWorld. My mother was lost there, and I won’t lose him, too.” Momentarily her expression melted, as her mouth turned down and her eyes flooded with tears she blinked away hard. She squared her shoulders, mouth set once more in its firm line, and Griffin groaned inwardly. He knew that look. It was the one she habitually wore whenever Dougal set a challenge before them both. “I won’t let them have him. I don’t have time right now to listen to a wicce-woman repeat some ancient story all of us have heard a thousand times. I’ll find Papa and bring him home if it’s the last thing I do, I swear.” She got to her feet and swung the ax over her shoulder. Her hair tumbled down her arms and she thrust it back impatiently. Her father’s insistence that she keep her black curls long was his one recognition of his only child’s sex. “Stand back.”

Aghast by her casual savagery, Griffin moved back as she brought the ax down, the blade grazing the goblin’s slack jaw by a hair. It bit through the flesh and gristle and stopped with a dull thud in the neckbone. She tugged the blade free and raised it once more, heedless of the red slime dripping from it, and in one smooth motion, brought it all the way down again. This time the blade buried itself in the earth, and the head lolled back, rolling slightly to one side on the slight grade. Nessa handed Griffin the ax, picked the head up by the hair and shoved it without flinching into the sack. From somewhere close, a cock crowed experimentally. “I have to hurry.”

She slung the sack over her shoulder and picked up the lantern, as he flung the ax aside with disgust. Easier by far to make a new one, than to imagine cleaning off that gore. “What am I to tell everyone?” he whispered.

“The truth, of course. Oh. Here.” She set the sack down and felt beneath her tunic for the slender cord which held her silver amulet. She bent her head and worked it over her chin and through the tangled length of her hair. “Take it.” She held it out and stamped her foot as the cock crowed again. “I don’t have much time.”

He caught it as it dropped from her hand, then stumbled after her, his mind roiling with disbelief and desperation. With sure steps she strode up the road, through the silent, sleeping village. The crunch of their feet on the cold gravel was the only sound, their breath curling in long white plumes through the predawn air. Not even a barking dog marked their passing. At the smithy gate, she paused. “No sense in you coming any farther.”

He hesitated. What would Dougal want him to do, other than locking her in the root cellar? Nothing seemed viable, but a thought occurred to him. “Wait,” he said. He ran into the house, grabbed a round loaf of bread and a hunk of cheese that one of the women had left. He reached for his own pack, a treasured gift from Dougal at last Solstice, and shoved the food inside. He ran back outside and thrust it at her. “Remember, you mustn’t eat or drink anything of the OtherWorld.”

She favored him with a quick surprised smile, then nodded and slung it on her other shoulder.

“I don’t think I should tell anyone the truth, Nessa, about where you’ve gone. Not unless you don’t come back after a day or so, all right? People already—” he hesitated, loathe to hurt her with a reminder of the shadow under which she lived. “Already talk.” Their eyes met, and hers were steady, full of sure and certain purpose.

“I guess you’re right,” she said.

It occurred to Griffin that he might never see her again. He wanted to take her hand, to tell her all the things he rehearsed alone at night. He was not ill-favored, they worked well together, surely the smithy would someday be hers. They were already a good team. Marriage was not such a ridiculous possibility.

Despite the chill, her face was covered by a fine sheen of sweat, and he thought she had never looked more beautiful. The words felt like a cork in his throat and he felt the moment passing, slipping away as inexorably as the night. He seized her by the shoulders and pressed a hard desperate kiss on her mouth. Her lips were warm and firm and she didn’t immediately recoil. Then she pulled away, and he half thought she might hit him. “Just come home,” he said by way of apology.

She raised her chin and squared her shoulders. “Count on it.”

Then the cock crowed once more. “Hurry,” he said, awed and grateful that she had neither slapped him nor wiped away his kiss.

With a nod of farewell, she strode down the road, veering off toward the thick stand of trees which lay between the village and the lake. The lantern bobbed in rhythm to her steps, twinkling like a star.

“Nessa. Don’t eat or drink anything!” he called after her, wishing the words were sufficient to change her mind and bring her back. But once Nessa made her mind up to do something, it was always easier to get out of the way.

“Best bank that fire,” her voice floated back to him on the wind. “Papa will have your head—” The rest was lost, carried off by the freshening breeze, into a half-heard murmur. The lantern flared once more as though she turned to wave, and then it blinked out, swallowed by the trees. He raised his hand, both in blessing and farewell, and saw a dark trickle edging down his palm to his wrist. He had clenched the amulet so hard, his hand bled.

The thick hide sack barely suppressed the reek of goblin flesh. Nessa shoved the heavy bulge on its leather strap behind her, trying not to think of the thing which nestled now on the curve of her rump. She squinted through the trees. The black forest rose around her, the tree trunks silent as sentries beneath the still star-studded sky. White mist swirled in mossy hollows, and a dense odor, musty and faintly sweet, rose from the forest floor and permeated the chilly air. But the scent of morning was on the light breeze which stirred the few leaves that clung to the late-autumn trees, and just now, behind her, where the village lay sleeping in the predawn quiet, she thought she heard another cock crow. She had less time than she’d hoped.

The soft squish of spongy cress beneath her boots assured her that she followed the thin line of the narrow stream that, snaking beneath the trees, led down to the lake. Streams such as this were called Faerie roads, and usually avoided. For the stream itself was nearly invisible, buried by the thick cover of fallen leaves, their edges crisp and sere. The stories said that water was one of the surest conduits between the mortal world and the OtherWorld, the one called TirNa’lugh in the old language. And it was said, it was during the in-between times and in the in-between places, when and where things were no longer one thing, and not yet quite another, that one was most likely to slip into this intersecting reality.

She quickened her pace, breathing hard, and out of force of habit, groped at her throat with one cold hand, forgetting for a moment that she had removed her silver amulet. For the first time in her nineteen years she was without silver. She felt naked and somehow wicked.

Well, it was wicked. Griffin was right. She dismissed his clumsy kiss as a product of anxiety and fatigue. And disbelief that she would do something so irrational. To accidentally fall into TirNa’lugh, victim of a sidhe’s spell, was one thing. But to remove one’s amulet and to deliberately seek to enter the OtherWorld, was an action so preposterous, Nessa knew of no one who’d attempted it. No one should know better than she the dangers lurking there. Surpassingly beautiful, with voices like music, a sidhe was capable of weaving enchantments so profound that humans willingly gave up home and family to follow their sidhe obsession, trapped out of mortal time, lost to all previously held dear. And, if some hapless mortal did find his or her way back, if he or she had tasted Other Worldly food or drink, he would refuse all human food, thus, to sicken and finally die. Or, even if he could force himself to take nourishment, he would find that while only a year or two had seemed to pass in the OtherWorld, tens or even hundreds of years would’ve passed in the mortal world, and everyone ever known was either old or dead, while his own body withered like an autumn leaf. Once it was known that she had deliberately removed her silver and walked into TirNa’lugh, the villagers were likely to add madwoman to their list of gossip. Enough of them believed she was tainted in some way by her mother’s actions, even though Nessa had been less than a year old when her mother had been spirited away by some sidhe lord who’d tricked her into removing her silver. Now she existed only as a faceless name in her daughter’s memory. Once she had asked her father why he had not sought to rescue her mother, and he had been silent a long time, as if carefully considering his answer. “Well,” he’d finally said. “There was you, you see.” And in those simple words, Nessa felt the pain of his choice.

Nessa tramped on. She would not lose her father. She steadfastly refused to even consider the possibility that he was dead. He could not be dead. He was all the family she had in the world, and she would not accept the idea of a life without him. Trouble was brewing in the land, civil war and general unrest sparked by a King gone mad and a foreign-born Queen whose large family eyed Brynhyvar with hungry speculation. Dougal had spoken of moving up to Castle Gar, and hinted that their skills might soon be needed on a greater scale than ever before. She would not face the village, the world, and war without him. She would find him or die herself.

The light was growing stronger now, long, silvery-gold shafts that streamed through the mist. She blew out the candle and set the lantern down on the forest floor. She would carry it no farther, for the less encumbered she was, the better. She considered dropping Griffin’s pack, but the food was too necessary. With a sigh, she shouldered it once more and set off.

The dawn was nearly over, and with it, her hope of entering the OtherWorld. Ahead, the trees seemed to thin, and through the spindly trunks spears of golden light spiked through the branches, a more intense light than that which seemed to fall about her shoulders. Is it the OtherWorld up ahead? she wondered, as she shifted the sack and gripped the hilt of her dagger. The ground was firmer now, all vestiges of the stream gone, and the thinnest rim of the rising sun just visible above the line of trees. It was nearly morning, nearly day, but the thought of her father ensnared by sidhe magic or goblin claw spurred her on.

She ran faster through the white birch trees, running into the elusive light which seemed to beckon just outside her reach. The spindly leaves shuddered as she passed, until she tripped on a half-hidden root and sprawled flat on her stomach. The goblin head bounced up and down on the earth beside her, and the flap opened and the reek which spilled out made her gag. Bright sun burst above the trees and daylight poured over her. She shut her eyes and banged her fists on the ground in frustration. It was gone. Her chance to find her way into the OtherWorld was over. Sweat broke out on her forehead and hot tears welled up, spilling down her cheeks. She brought one hand to her face, sobbing as she lowered her head to the ground. Griffin was right. She must be mad to have even thought to attempt such a thing. But I won’t give up, she vowed. If the Duke’s men did not come today, she would try again tomorrow. She sniffed and noticed then that the moss beneath her cheek was soft and thick and smelled almost sweet. Soft and thick as flannel after many washings or the herb known as lamb’s ears, and she opened her eyes, pushing up on her elbows to stare down at it, for it was an emerald-green so intense she doubted she could’ve imagined such a color existed. Wondering, she stroked it, for it felt amazingly smooth against her fingertips, tips that suddenly appeared rough with scars and hard with calluses and very, very dirty. The scent that rose from the moss was fragrant, like sun-warmed earth in spring, and she closed her eyes and breathed in deep.

A sudden hiss made her head snap up.

“Horned Herne, maiden, what do you here?”

The deep voice startled her, so that she scrambled back in a half-crouch, warily straightening, wiping away her tears. The speaker, who stood in the shade of an oak with sprawling branches thick with bright golden leaves, looked unlike anyone she’d ever seen. He was broad of shoulder, the strong cords of his neck just visible above the high linen collar of the shirt he wore beneath a doublet that was made of something that looked even more velvety than the moss. It was nearly the color of the moss, too, and she saw as he emerged from the shadow of the tree that it exactly matched his eyes which slanted above his high, narrow cheekbones. A braid, thick as a woman’s, the color of a honeycomb with the sun gleaming through it, hung over his shoulder, like a silky rope that seemed to invite her to stroke it, to wrap it around her neck and arms, just to feel its texture glide across her skin. There was an intricate insignia embroidered on the shoulders and across the chest of his doublet, and she looked at his face, questions forming in her mind. His lips were plump as peaches, red as apples, and his eyes seemed to burn through her, as though he knew exactly what she was thinking. She lowered her eyes as she felt the color rise in her cheeks, noticing that his chest tapered to a narrow waist and hips, how his hose clung like a glove to his muscled thighs and calves. He held a bow, with arrow knocked and ready. She drew a deep breath, and would have answered, when he muttered what sounded like a curse, and beckoned. “To me. Now. Quickly.” He raised the bow and she nearly startled back, then realized he aimed at something just beyond her. “Now, maiden!”

She hastened to his side, grabbing for the sack and Griffin’s pack, a thousand questions bubbling on her lips. Beside him, she felt herself to be disgustingly dirty, covered in filth and soot and grime, and she wondered how he could stand the smell of her, but he only thrust her behind him, and stood, tensed and ready. The moment hung, suspended, and she wondered if he could hear the pounding of her heart.

The attack took them both by surprise. From the side, a hulking gray shape rushed out of the trees, in a cloud of stench and a rush of leather, a long snout and thick arms which held a giant broadsword of some metal that gleamed with a dark sheen.

But the bowman was quicker. Without flinching, he drew the bow, and the arrow sang across the narrow clearing, landing with a dull thud into the chest of the creature that snarled and lunged even as it collapsed. Nessa stared in horror at the thing that lay in a crumpled heap, its leathery tail still twitching.

Beside her, the sidhe reached over his shoulder for another arrow. “You are just over the border betwixt our worlds, maiden.” He spoke in a low whisper as he fitted the arrow into the bow. “I shall see you back across. It isn’t safe for you here. We stand too close to the realm of the Goblin King. The wards here must be weaker than we realized.”

Nessa gulped. It seemed impossible that such a slender stalk of ash was sufficient to have slain the goblin, but there it quivered in the monster’s chest. Swallowing hard, she wrapped her wet palm in the fabric of her tunic, and tried to stop shaking. “I—I don’t want to go back. I—I came to see the Queen. To show her this.” Without taking her eyes off the still creature in the center of the clearing, she held out the bag.

He frowned as if he wasn’t sure he’d understood her. “You’ve come deliberately into Faerie?” He lowered the bow after a quick glance around the clearing. “And what manner of gift is this?” He frowned at the rude leather, and Nessa felt the full measure of his scorn in his look.

“This isn’t a gift. It’s the—the head of one of—” She paused, gesturing with her chin in the direction of the goblin. “One of them. It was found dead on the lakeshore near my village.”

The color drained from his already pale face. “A lake in the Shadowlands? That cannot be.”

“This is what we found. Is it not kin to that?” She nodded in the direction of the dead creature, and held open the bag. The stench that rose from it was noxious and rank, and made the sidhe grimace in disgust. “And in the same hour that this was found, my father went missing.” She stared up at him with mute appeal. She felt the impact of his eyes meeting hers with nearly physical force. “I came to ask her for her help.”

“By the Hag, maiden, shut that away.” He waved one hand in front of his face. “What’s in that other sack?”

“Food.” She thought briefly of Griffin, how clumsy and crude he seemed beside the sidhe. He seemed a thousand leagues away. Was it only a few minutes ago that he had thrust it in her hands?

“I see. You even brought provisions—how wise. How long has your father been missing, you say?”

“Since the dinner hour last evening. He was going to the lake when he left the smithy.”

“And who killed the goblin?”

“We couldn’t tell. There was a long slash in its belly and half its guts had spilled out. But there was no sign of a weapon, or a battle, or my father.”

He rubbed his face and gazed around, forehead puckered. “There is a lake that lies that way, yonder, over the border of the Wastelands. You indeed are fortunate that if a lake so like it lies so close in Shadow, you stumbled over on this side, and not on that one.”

“What is shadow?” she asked, stabbed by a pinprick of the realization that the possibility which she refused to consider—of a world without Dougal—might, in fact, be far more than a possibility.

“The Shadowlands. The world of mortal men. And maids. You call it Brynhyvar.” He turned back to look at her, and their eyes met once more. Her heart stopped in her chest, as he turned the full force of his piercing green gaze on her. A flush was rising in his face and a small pulse beat a quickening tattoo in his neck just above the collar of his tunic. His skin had the texture of velvet and reminded her of the color of cream. A sweet, fresh scent emanated from him, a scent that reminded her of new fallen snow on pine boughs. “So this is the spell you mortals cast,” he muttered, more to himself than to her. “Like midsummer wine and winterweed.”

Despite a deepening sense of despair, she stared, fascinated by the shades of green swirling in his pupils. Every sense felt inflamed, swollen, and her head was beginning to spin in slow thick circles. She bit down hard on her lip and the taste of her own blood steadied her. She hefted the sack over her shoulder again. She would not lose sight of why she’d risked just this very thing. But she was terribly conscious that her clothes lay rough over her body, crudely made, as if cut by a child’s hand compared to his, and that there were wedges of grime beneath her fingernails, that her tangled mane of dark curls hung in lank, sweat-soaked strands about her dirt-and tear-streaked face. But the way he was looking at her made her feel as if he wanted to devour her. She coughed. “I’ve come to find my father.”

He shook his head, as if to clear away the effect of the attraction, and took a step back. “Maiden, if he fell out of Shadow and into the Wasteland beyond—the Goblin Wastes—” He broke off and sighed, as if reluctant to say more. “I cannot give you the help you seek or even take time now to explain the implications of the news you bring. I can, however, take you to one who quite possibly will help you, to the extent that he can, once he hears your story. For it would appear that if indeed a goblin has somehow fallen into the Shadowlands, even a dead goblin, then a greater magic than expected has failed, and the Queen herself must know of this. No one’s been expecting this—things could go very badly indeed for all of us if what you say is true. You must come with me.” He turned on his heel, still shaking his head, clearly loathe to continue, but anxious to go on.

“But, but wait—” She stumbled after him, hurrying to keep up in boots that suddenly seemed clumsy and stiff, ignoring every injunction every goodwife ever whispered at the end of every tale involving the sidhe. “What about the Silver Caul? Isn’t it supposed to keep the goblins out of Brynhyvar? Why isn’t it working? Is that the magic you mean has failed?”

He turned and made an impatient gesture. “Hurry, maiden. There will be time enough to explain it all to you in safety.” He stretched out his hand and she realized he was wearing gloves of leather so finely wrought they fitted with no more wrinkles than his own skin. “Come. I dare say no more here.”

Was this not what she’d come for? It was too late to have second thoughts now, even as the ferocity with which the goblin had attacked sparked the doubt that perhaps Griffin was right and that the OtherWorld was far too dangerous a place for her to be wandering around in alone.

With a quick nod, she let him guide her through the trees, his steps quick and sure, following a narrow trail which threaded through a thick forest of golden oaks and yellow beeches and blazing red maples. They had gone not even half a league when he stopped suddenly and pulled her close to him, one finger pressed hard against her mouth. Her senses exploded as she inhaled a scent at once so vital and pristine it felt as satisfying as food. No wonder mortals withered, rejecting coarser, more substantive nourishment. Without thinking, she leaned into him involuntarily. Their eyes met again and it felt as if her blood had turned to molten metal in her veins. She thought of Griffin’s clumsy kiss, and knew this as different as a ripple from a wave. But the sidhe closed his eyes and turned his head. “Maiden,” he said, in a whisper so low, she partly read his lips, “make no sound.” For one brief moment, they swayed closer, while she wondered idly in some remote corner of her brain, the possible source of his attraction to her, for she felt herself to be unbearably dirty and disheveled, her clothes and hair stinking of goblin. And then she heard the low grunt.

A cold wave of fear ran down her back as he lifted a horn off his shoulder and handed it to her, then drew the sword out of its scabbard. The brisk leafy-scented air was suddenly polluted by something that stank of the cesspits, a stink she recognized far too well. He drew a breath and swung his sword up, circling around her. “That track beneath the trees, maiden, will lead you to my fellows. Run hard, and blow the horn. They will be alerted to my need and take you to my Captain. Do you understand? You must run, quickly, maiden, upon my signal.” He pointed with the sword at the track, which threaded through the trees. “You must run. And you must not look back.” He moved around then, pushing her behind him. Suddenly he shouted, “Go!” as three goblins armed with battle-axes roared out of the trees.

Nessa charged down the trail, the sack with the head thumping against her rump. Thank the Great Mother that her father had seen fit to let her run with the boys of the village, and not confined her to kitchen and courtyard like the rest of the girls. Her boots felt weightless as she sped in the direction her rescuer had indicated and she lifted the horn to her lips, and blew. The horn sounded one pure clear note, and it echoed through the trees, loud and long. Immediately another horn blew in answer, then another, and she raised the horn once more, dropping Griffin’s pack off her arm. It slid to the ground, as she blew hard into the horn again. Sudden movement in the trees all around her made her knees quake, and she stumbled in midstride. Forgetting the injunction not to look back, she glanced fearfully over her shoulder, and in that moment, collided with a solid form that gripped her with steady arms. She twisted her face up and around and gasped to see a sidhe, every bit as beautiful as the other, staring down at her. “By Herne’s horns,” he said, in a voice as richly sweet as honeyed wine, even as he gestured his fellows to continue on in the direction from which Nessa had come, “a mortal maiden, as I live and breathe.”

3

It was always the light that Timias noticed first whenever he transversed the fluid borders between the Shadowlands and Faerie. Elusive and fey as the sidhe themselves, it shimmered through the trees, limning the edge of every leaf, pulsating with seductive radiance. More than one mortal had become a captive to the glamour cast by Faerie light, bound for mortal ages by fascination with its constantly shifting play of contrasts more acute than any ever cast by the bleaker sun of Shadow.

Now he strode through the thickest part of the stream, the bottom of his staff encrusted in mud, moving as quickly as his aged bones would allow. In mortal years, he was old beyond reckoning, but he, unlike most sidhe, bore the stamp of it upon his face. For Timias had dared to do what few would even contemplate—he had lived among the mortals, allowing the harsh mortal years to take their toll upon his face. His frame was bent, his face was lined like a walnut, the hair which hung in long silken strands around his shoulders was gray. He had thought, once, that the mortal woman for whom he’d given up one lifetime in the Shadowlands, though not a tenth of that in Faerie, had been worth the price he’d paid. Now he wasn’t so certain. For when he’d returned to Faerie, to claim his place among the Councilors to the Queen, he found that Vinaver, that foul abomination, the Queen’s twin, had managed to convince several among the lords and ladies of the Council that so long a sojourn as his in the Shadowlands represented some kind of technical resignation and a vocal few had even had the audacity to call for his removal.

In retrospect he should have expected such a move on Vinaver’s part. They had been instinctive enemies from the moment of her birth. Timias would never forget how the infant, born aware as all the sidhe, had hissed and spat directly into his face when the midwife had placed her into his unwilling arms. From that moment, Vinaver had worked to do all she could to discredit him with her sister, the Queen.

But Timias had a hereditary right to a seat upon the Council—the most honored right of all in Faerie—and no one had ever heard him surrender it. And so he kept his seat, but it was not as before. For he had been irrevocably changed by his extended time spent among the mortals, and in Faerie, change usually happened so gradually it was hardly discernible at all.

Each day in Faerie was as glorious as the day before it, a long progression of hours that flowed as sluggishly as a lazy river. Few things in the Shadowlands could compare to the stately pace of Faerie time, and nothing within Faerie could equal the breakneck speed with which life progressed in Shadow. It was that, as much as anything that had prompted Timias to stay in the Shadowlands so long. Mortals may not live as long as the sidhe, but their lives were lived more intensely. To one accustomed to the leisurely flow of Faerie time, it was as intoxicating as an inhalation of winter dream-weed.

But if his had been an unexpected return, it was also very timely, in Timias’s opinion. For it was immediately clear to him that Alemandine was not the Queen her mother, known as Gloriana the Great, she who’d vanquished the Goblin King and constructed the Silver Caul which kept the deadly silver out of Faerie, had been. Compared to Gloriana, Alemandine was only a pale shadow of the great Queen whose reign had ushered in this Golden Age that had endured for more than a thousand mortal years. Gloriana had birthed her triplets, Alemandine and Vinaver, and her half-mortal son Artimour, without so much as a hiccup in the great webs of power that held the goblin hordes at bay, and Timias was disgusted that it was whispered in some quarters of the Court that Vinaver, who in both coloring and temperament more closely resembled her mother, should have been Queen. Vinaver’s hair was like her mother’s fiery-copper, her eyes the dark green of mountain firs. Alemandine’s hair was white, her skin paler than milk, her eyes like chunks of river ice chipped from the shallows. It was as if Vinaver had somehow sucked up all the pigment out of her twin, as if she would’ve claimed all the life, all the energy for herself. He disliked her just for that.

But tradition, of course, was on Alemandine’s side and so she had taken the throne when the time came at last that Gloriana chose to go into the West. For the first hundred or so comparative mortal years of her reign, Alemandine ruled competently, if with a less sure and certain hand than her mother. The trouble began with her first attempts to call forth her own heir, when the physical strain of her pregnancy seemed greater than it should, and Timias believed that on this short visit to the Shadowlands, he had identified a potential cause that could, with some effort, be ameliorated. Unfortunately it was difficult to persuade the Council of anything, for Vinaver and her supporters managed to convince the others that he was merely the mad sidhe overcome by his addiction to human passion. It was an image he found difficult to combat. For in Faerie, appearances were everything, and the toll of mortal years had cost him more than he cared to admit.

But Timias, who had been present when the Silver Caul and moonstone globe were created and joined together, understood how closely the Caul and the globe bound the worlds, Shadow and Faerie, together so that events were reflected, repeated and echoed in each other. As long as both remained relatively stable, all was well, petty mortal squabblings over land or gold reflected in the trivial intrigues that permeated the Court. The realization that this relationship also created a largely unacknowledged potential for a spiral into disaster prompted Timias to cross the border into the Shadowlands once more.

What he found made him hasten back as quickly as he could. For the war now breaking out in Brynhyvar, the land lying closest to Faerie of all mortal lands, was one which threatened to spill over its borders and engulf the entire mortal world. The situation there only intensified the growing sense of dread he’d begun to feel when Alemandine’s pregnancy was first announced. For while an heir was long overdue, the Goblin King was waiting—waiting for the chance to overcome the bonds of sidhe magic and to overthrow the Queen while she was her most vulnerable. The time of her delivery would be perilous enough—he did not want to consider how full-scale war in Shadow would affect them all, if it coincided with an assault by the Goblin King. The forces of chaos were massing. They must prepare to fight the war on all fronts—including the Shadowlands, if necessary. He glanced up at the piercing blue sky and hurried as fast as he could, hoping that he could catch the Queen in a well-rested mood. For he had noticed that while the Queen might prefer to ignore him, she listened to him more carefully than she oft-times appeared, and that frequently she summoned him to a private audience to discuss the issues he raised. She had always, he wanted to think, regarded him as one of her more trusted Councilors, for he always told her the truth, no matter how unpleasant. It assuaged the remnants of his dignity, and reminded him of the time when he had, indeed, been Gloriana’s most trusted Councilor, her closest confidant, more intimate than her unremarkable Consort, whom she’d chosen for his ability to dance and to compose extemporaneous verse.

But even as he strode up the bank to the footpath which led to the wide gardens surrounding the Palace of the Faerie Queen, he knew what he intended to propose would sound too radical, too incomprehensible to be taken seriously. Blatant and obvious intervention into the affairs of the Shadowlands had never occurred, not even by Gloriana in the Goblin Wars when mortals and sidhe had struck an alliance. Without any precedent, he would have to hope the Queen was in a receptive mood.

He rounded a curve and the trees thinned, opening out onto a broad lawn that swept like a wide green carpet to the white walls of the palace gardens. He looked up as the sun rose above the trees, illuminating the blue and violet pennants which fluttered off the high white turrets. A thousand crystal windowpanes gleamed like rubies, reflecting the red sun as it rose, and on the highest turret, a white silk banner floated on the morning breeze, flashing the Queen’s crest, announcing to all who might have cared to inquire that the Queen of all Faerie was in residence within. She was about to leave soon, he knew, and that, too, was cause for concern. Although tradition demanded that each year she retire to her winter retreat on the southern shores, Timias feared the journey would tax her strength unduly. But Alemandine insisted, clinging to the hidebound traditions like a life rope.

He had a trump card to play, he thought, if he dared to bring it up. There was the lesson of the lost land of Lyonesse, which had once lain to the east of Faerie. It had disintegrated into nothingness one day, collapsing in and over and upon itself until it was no more. Now even the memories of its stories were fading, for it was said that the songs of Lyonesse were too painful to bear. But to imply that Faerie itself stood so close to the verge of ultimate collapse when he was not at all certain that such was actually the case might unduly alarm Alemandine and thus hasten, or even cause the calamity. He needed to convince the majority of the Council to heed his advice, not frighten the Queen, he decided. And to that end, he would seek to use every weapon at his disposal if necessary. But first he would seek to reason with Her Majesty.

So he hastened past the high hedges of tiny blue flowers which opened at his approach, scenting the air with delicate perfume that faded nearly immediately as he passed, trying to think of the correct approach. The lawn ended in a wide gravel path, which opened out onto a broad avenue that encircled a shimmering lake. Ancient willows hugged the shore, branches bending to the water. The sun was nearly above the trees, and the gold light sparkled on the surface. At this hour, both lake and avenue were deserted, but for the gremlin throwing handfuls of yellow meal to the black swans floating regally on the lake.

The gremlin turned his head as Timias passed, fixing him with a hostile stare. Timias met the gremlin’s eyes squarely. There were increasing reports of little incidents of rebellion among the gremlins, who, according to the Lorespinners, had been bred of goblin stock to serve the Faerie. The incidents were generally dismissed as the approach of the annual bout of collective madness that occurred among the entire gremlin population at Samhain. The other obvious threat seemed to elude everyone. When Timias had suggested to the Council, that the gremlins, as distant goblin kin, might find it in their best interests to side with the goblins in the coming conflict, and that being in a position to bring about utter ruin, they might be better banished to some well guarded spot until the child was born, he was laughed at openly throughout the Court. But Timias feared the time was coming when the courtiers wouldn’t be so amused. He would find that thought amusing himself if the consequences weren’t so dire. He picked up his pace, leaning heavily on his oak staff as his aged legs protested.

Once within the palace walls, he didn’t pause on his way through the marble corridors, not even stopping to visit his own apartments. He ignored the fantastic mosaics, the silken hangings, the intricate carvings which graced the palace at every turn, a blend of color, scent and texture so harmonious, mortals had been known to gape for days at just the walls. He strode beneath the gilded arches to the Council Chamber, where the guards straightened to attention and saluted as he approached. But at the open door he paused and peered in, ostensibly smoothing his travel-stained garments, assessing as he did so who was in attendance and their likely reaction to his news.

As he expected, the Queen was at her breakfast, attended by her Consort, Prince Hudibras, and those of her Councilors in residence, and to his dismay, he saw that Vinaver sat at the Queen’s right hand. Perhaps he’d do better to approach the Queen privately.

The idea that Vinaver, who he had always regarded as some mutant perversion of the magic that created the Caul, was able to enthrall her sister with her wiles sickened him. It had been terrible enough to discover that Gloriana’s womb housed two babes—Alemandine and Artimour—fathered separately by a sidhe and a mortal on the same night as the forging of the Caul. But Vinaver’s emergence was completely unexpected, completely unforeseen, an aberration of the natural order of Faerie Timias thought best disposed of. He’d suggested drowning the extra infant to the midwife who’d brought her out for his inspection. The infant’s eyes clashed with his almost audibly, and he felt the desperate hunger stretching off the wriggling scrap of red flesh like tentacles, seeking any source of nourishment. He shook off the infant’s rooting with disgust. “I say drown it,” he said again, shocking the midwife into silence as she turned and carried the infant back to her mother’s arms, to wait her turn for a tug at her mother’s copious teats. Both Vinaver and Artimour were offenses against nature, he’d argued then, arguing tradition, just as he’d argued it when he returned and fought for his Council seat.

He wondered what Vinaver might have been up to in his absence, for any differences between the Queen and her sister that he might have nurtured had obviously been resolved. Vinaver leaned forward with a proprietary hand to caress her sister’s forearm as it draped wearily over the cushioned rest of her high-backed chair. Vinaver’s back was to him, and Alemandine was turned away, engaged in choosing a muffin from the basket the serving gremlin offered. The creature wore cloth-of-gold, signifying the highest level of service. The hackles rose on the back of his neck. If only he could induce the Queen to at least banish them from her immediate service.

But it was the others who were gathered around the table that made him narrow his eyes. For with the sole exception of the Queen’s Consort, Hudibras, they were all Vinaver’s closest cronies. Across from Vinaver, on the opposite side of the table, Lord Berillian of the Western Reach sipped from his jewel-encrusted goblet, his attention focused on a dark-haired girl who sat beside him. Timias did not immediately recognize her, but something about her face made him pause, and he realized she was gowned in an old-fashioned gown of Gloriana’s era. He realized that they paid him no mind for they were all focused on her and the room was thick with some suppressed tension.

Several vacant seats apart, Lord Philomemnon of the Southern Archipelago, peeled an apple with overly deliberate intent, while at the opposite end, the Queen’s Consort, Hudibras, caught another tossed to him by his half brother, Gorlias.

Both Philomemnon and Berillian were Vinaver’s closest cronies and cohorts, the voices who’d championed her cause most vigorously in the early days of Alemandine’s reign, who’d shouted most loudly for his resignation.

The early-morning sun flooded through the wide windows which lined one wall of the long chamber, and glinted off the polished surface of the inlaid table that dominated the furnishings. Fragrant steam wreathed the air, redolent with the rich feast spread before them on golden serving plates.