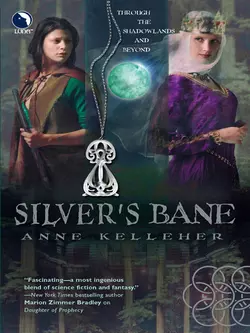

Silver′s Bane

Anne Kelleher

THROUGH THE SHADOWLANDS: Where the touch of silver was Protection, Power and Peril… AN OTHERWORLDLY INTRIGUE… With the courts of both the Sidhe's Otherworld and the mortals' Shadowlands in contention, nothing seems safe anymore.Now blacksmith's daughter Nessa is caught up in political and military intrigues that might loose the goblin horde. Widowed queen Cecily is fighting for a throne she never expected to have. And Delphinea, lady in waiting to the Faery throne, is caught between the powers of Sidhe and her destiny.A DESPERATE PERIL…The first battles are over, and devastation wracks both lands. With Nessa crossing between worlds to further understanding of each people, Cecily and Delphinea must fight to contain the evil that edges ever closer. Because their honor demands that their countries come before anything–even love. And life…

Praise for Anne Kelleher

“Anne Kelleher’s engrossing fantasy, Silver’s Edge…weaves an enticing tale as Nessa braves unknown dangers to find her father and bring him safely home in this beguiling story of courage and adventure.”

—BookPage

“Ms. Kelleher weaves another fantasy epic of grand proportions, sweeping the reader off into lands, legends and lore. Part Arthurian, part Tolkien and part fairy tale, the mix creates an incredible world for the reader’s fertile mind to take root. It starts off slowly, but then takes off with a bang and never releases you from its grasp.”

—The Best Reviews, on Silver’s Edge

“The characters are complex and multifaceted, and the writing is rich with colorful prose…. Women control their fates, and fear is not an option when it comes to the tough decisions that must be made in a time when all that is held sacred is facing destruction.”

—Romance Reviews Today on Silver’s Edge

“Silver’s Edge is a first-class fantasy. The characters are vivid, believable; they captured this reader’s heart, taking me on an unforgettable journey as they confronted their fears, made tough decisions and accepted the consequences of those decisions, no matter what it cost them.”

—In the Library Reviews

“…displays vivid imagination.”

—Publishers Weekly

“Fascinating—a most ingenious blend of science fiction and fantasy.”

—New York Times bestselling author Marion Zimmer Bradley on Daughter of Prophecy

SILVER’S BANE

ANNE KELLEHER

This book is dedicated with love to all the women

in my life—friends, teachers, mentors, guides and

guardians who are far too many to list—and most

especially to my mother, Frances Kelly;

my stepmother, Alice Kelleher;

my grandmother Rose Castaldi;

my sisters, Sheila Kelly Bauer, DJ Kelleher and Pam Boyd;

my daughters, Kate, Meg and Libby; all those yet to

come and all those who have gone before.

Blessed be.

Glossary of People and Places

Faerie—the sidhe word for their own world. It includes the Wastelands

The Shadowlands—the sidhe word for the mortal world

The Wastelands—that part of Faerie to which the goblins have been banished

Lyonesse—legendary lost land that is said to have lain to the east of Faerie

Brynhyvar—the country that, in the mortal world, overlaps with Faerie

The Otherworld—the mortal name for Faerie

TirNa’lugh—the lands of light; the shining lands—mortal name for Faerie; becoming archaic

The Summerlands—place where mortals go at death

Humbria—mortal country across the Murhevnian Sea to the east of Brynhyvar

Lacquilea—mortal country lying to the south of Brynhyvar

Killcairn—Nessa’s village

Killcrag—neighboring village to the south

Killcarrick—lake and the keep

Alemandine—Queen of sidhe

Xerruw—Goblin King

Vinaver—Alemandine’s younger twin sister and the rightful Queen

Artimour—Alemandine’s half-mortal half brother

Gloriana—mother of Vinaver, Alemandine and Artimour

Timias—Gloriana’s chief councilor and the unacknowledged father of Alemandine and Vinaver

Eponea—Mistress of the Queen’s Horses

Delphinea—Eponea’s daughter

Finuviel—Vinaver’s son by the god Herne; rightful King of Faerie

Hudibras—Alemandine’s consort

Gorlias, Philomemnon, Berillian—councilors to the Queen

Petri—Delphinea’s servant gremlin

Khouri—leader of the gremlin revolt and plot to steal the Caul

Nessa—nineteen-year-old daughter of Dougal, the blacksmith of Killcairn

Dougal—Nessa’s father; Essa’s husband; stolen into Faerie by Vinaver

Griffin—Dougal’s eighteen-year-old apprentice

Donnor, Duke of Gar—overlord of Killcairn and surrounding country; uncle of the mad King and leader of the rebellion against him

Cadwyr, Duke of Allovale—Donnor’s nephew and heir

Cecily of Mochmorna—Donnor’s wife; heiress to the throne of Brynhyvar

Kian of Garn—Donnor’s First Knight

Hoell—mad King of Brynhyvar

Merle—Queen of Brynhyvar; princess of Humbria

Renvahr, Duke of Longborth—brother of Queen Merle; elected Protector of the Realm of Brynhyvar

Granny Wren—wicce woman of Killcairn

Granny Molly—wicce woman of Killcrag

Engus—blacksmith of Killcarrick

Uwen—Kian’s second in command

The Hag—immortal who dwells in the rocks and caves below Faerie; the moonstone globe was stolen from her when the Caul was forged

Herne—immortal who dwells within the Faerie forests, from which he rides out on Samhain night, leading the Wild Hunt across the worlds

Great Mother—mortal name for the Hag

The Horned One—mortal name for Herne

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Special thanks to Rosmari Roast, herbalist, wise woman and friend, for eleventh-hour research; to my agent, Jenn Jackson, and my editor Mary-Theresa Hussey for seeing the potential before I did; to Laura Rose and the rest of the Goddess Girls: Anne Sheridan, Susan Grayson, Leslie Goodale, Lisa Drew, Barbara Terry, Jamie King, Louise Rose, Alicia Tremper, Judy Conrad—you guys are the best midwives in the world; to Judy Charlton for reiki; to all the folks in the CT over 40 chat room on AOL, especially GtimeJoe; to all my fellow LUNA-tics in the LUNA-sylum for cheerleading. But most of all, this book would never have been written without the unwavering love and unstinting support of one man: Donny Goodman, I adore you.

Contents

Before

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Afterward

BEFORE

It was the weight of the world above her that nearly drove Vinaver mad. The thought of it crept, unbidden and unsought, from the deep places of her mind, a fat white worm of fear threatening to suffocate her from within, even as she struggled through narrow fissures and sloping corridors of unyielding stone. The pressure bore down on her from all directions, and the fear rose, writhing and squirming, coiling and expanding, filling her lungs, constricting her throat, wetting her palms, so that the lych-light at the end of her slim hazel-wood staff dimmed to a pinprick until she felt she would be swallowed by the dark.

The solid rock surrounding her was nearly as foreign to the intrinsic nature of her kind as the deadly silver from the mortal Shadowlands, for the sidhe of Faerie were creatures of light and air. But Vinaver had been forced to learn the first time her journey had taken her into the places where sunlight was not even a legend, that when the longing for the light and airy open spaces threatened to overwhelm her, she should close her eyes, and breathe, and let the crushing sensation roll over and through her like an enormous wave, until her mind quieted, leaving her feeling as exhausted and battered as the sea after a storm. But at least she was able to grip her staff and go on.

This was the last place anyone would ever think to find a sidhe. Her kind were never cave dwellers, stone carvers or earth diggers. According to the Lorespinners, the Un-derlands had been the realm of the goblins once, in the earliest time before the great Goblin Wars, when the sidhe, led by Vinaver’s mother, the great Queen Gloriana, had bound them into the Wastelands above. At least they’d still been bound in the Wastelands when Vinaver had started on this quest. She had no idea how long she’d been below the surface. There was no day or night, there was no sun or moon to mark the passage of hours, or the advance of seasons. She found the longer she was there, the less time had meaning.

But the domesticated trees within the Grove of the Palace of the Faerie Queen, as well as the wild ones of the Forest, had been adamant. Only the Hag—She who dwelled in the dark places below the surface world—could tell Vinaver why her sister, Alemandine, had failed to become pregnant with the heir of Faerie in her appointed time.

Now Vinaver followed the creature that slithered before her, a near-formless thing that gleamed wetly as it led her through granite canyons, leaving a trail of its own slime, its face perpetually turned away from the yellow glow of her lych-light.

Just beyond a jagged outcropping, her guide paused and drew back, indicating a tunnel leading off to one side. Vinaver stopped. The thing wanted her to follow it. She crept cautiously forward, feeling her way down the rough walls with fingertips made exquisitely sensitive. She peered inside the black slit of the opening. Patches of lichen glowed as she extended the staff as far into the tunnel as she could, and frowned as she saw that the roof sloped away into a low opening that disappeared into deep and utter blackness. It appeared barely wide enough for her shoulders. She’d have to slither through it, wriggling like a worm. Her breath caught in her throat at the thought of the massive rock surrounding her on all sides, and she nearly turned, shrieking, maddened beyond reach, dashing back like a butterfly trapped in a net, frantic for the taste of sun and air. I cannot do this, the voice of her own panic screamed through her mind, as she gripped the hazel staff with wet, white-knuckled fingers. But you must do this, she thought immediately in response. And she forced herself to breathe.

The world above was sick. The trees whispered it in their branches, sighed it in the wind. What beauty Faerie possessed was illusory, fleeting, and fading even as she lingered. If she failed to find out what could be done to heal the land, everything and everyone in Faerie would be lost forever, dispersed into some chaotic void, forgotten and forsaken. Her son’s image rose up unbidden, and her heart contracted that such grace and beauty as was his should be wasted. Finuviel. She saw his coal-black curls and long green eyes, high cheekbones and slanting brows and a smile that contained within it everything right and good and beautiful of Faerie. For him, she thought. For Finuviel, I will do what I must. She closed her eyes and concentrated on the air rushing in and out of her lungs, summoning up the strength to let herself be led into that dark and narrow passage. Finally she was able to nod.

Her guide had withdrawn, crouching in a formless lump. It had no eyes but she knew it watched her. So she nodded again and waved the lych-light. The creature shuddered away from the light, but gathered itself up into a sort of ball and slithered forward.

Disgust roiled through her but she tamped that down too. With a final breath, she entered the narrow tunnel. Almost immediately she was forced to bend, then to hunch, and finally, just as she feared, she was forced to crawl, first on all fours, and then, creeping and squirming like the thing before her. She found that she was grateful for the fluids the creature exuded, for they slicked the walls, easing her passage, even as she battled the panic that threatened to undo her completely when she felt the rock walls close in around her head.

She tumbled out at last, wet with sweat and slime, and she raised her face to the rush of cold still air and looked up into a vaulted cavern covered in tiny pinpricks that resembled infant stars. It was the lichen, she realized.

The thing quivered. The stone beneath her bare feet was smooth and very cold and white mist rose from the surface of a vast, still lake. Within it, patches of luminous phosphorescence lit the whole chamber with a pale greenish glow. An underground sea, she thought. But the thing at her feet was moving again, squirming down the sloping lip to the very edge of the water. It roiled and shuddered and a single arm formed out of the shapeless mass, and a rough approximation of a hand pointed a stubby finger. Vinaver squinted. In the middle of the water, behind the shifting mist, she saw a cluster of boulders that rose from the center of a small island some distance from the shore. “Is that where She lives?”

The words hung flat as if the water somehow absorbed the sound. A heavy stillness permeated the moist cold air, a silence so profound, she could feel the skin stretching over her sinews, the air moving in and out of her lungs, the pulse of her blood against the walls of her veins. Her tongue felt sharp as crystal against the dry leather of her mouth. That this could be the end of all her wanderings made her knees weak and her heart pound like a hammer against her breastbone.

But the wide water lay between her and the Hag, and there was no other way across as far as she could see. She would have to swim. Her breath hung like the mist over the sea. The thought of immersing herself in that cold bath made her bones ache. It had been so long since she’d been truly warm, she thought. She touched her face with one cold hand. She could scarcely remember a time when her muscles were not knotted and stiff, when her bones did not feel like flesh-covered lead. She did not want to bathe in that greenish glowing water. The great rocks themselves seemed to shift and groan and sigh all around her and the stone beneath her feet undulated as if a great beast stirred from some black unbroken sleep.

Vinaver looked down at the thing crouching at her feet, throbbing in time to a silent pulse, and she understood that it had brought her as far as it could. The rest was up to her. She removed her cloak and her gown—what was left of them—and placed them neatly on the stony shore beside her leather pack and the hazel rod. The lych-light faded to a faint twinkle. The gooseflesh prickled her skin and she crossed her arms over her breasts, then walked barefoot, naked but for the ragged chemise she wore, directly down to the water.

The first few strokes were a pleasant surprise. For far from being cold, the water was warm, welcoming as a hot salt sea under a summer sun. She stretched and relaxed into it, her strokes purposeful and sure, steady as the warmth that seeped into her legs and down her toes, caressing her with a deliberateness that was almost aware. Around her the white mist rose—not mist, she thought, but steam—drifting off the surface. She could see the island rising black and barren in the center. She swam on, the warmth bolstering her and sustaining her, trailing through the long locks of her coppery hair like a lover’s fingers.

It was when the water began to thicken around her that she began to worry, that she realized that what she swam through was not water such as that which coursed through the rivers of Faerie, nor even the salt ocean that surrounded it on all sides, but some strange primal sea, and her heart clenched as she saw long, shadowy strands and huge clumps of glutinous fiber swirl through the depths, like shadowy leviathans roaming the deep. If one of those things takes me, I shall be lost, she thought, and she stroked harder, kicked faster, even as the water gathered around her, congealing into rubbery strands. Dismayed, she kicked harder as the stuff twined around her limbs, sapping her strength. But still she had hope, that here, at last she had come to where the Hag dwelled, and she whipped her hair out of her eyes, stroking desperately toward the savage-looking boulders rising tantalizingly, mercilessly, just out of reach.

At last, when finally she thought she could stand no more, her feet touched solid stone. Nearly weeping, she looked down at the thick gelatinous clots that swirled and clumped around her ankles and her calves. She wiped and kicked them away, shuddering with disgust at the way the stuff persistently slimed around her as she plowed up the steep slope. Her teeth began to chatter audibly even before her knees broke the surface of the sea and she clutched her arms close about herself, shivering in the cold, cold air, even as she scraped the thick slime off her chemise and her skin, raking it out of her hair. At last she stood on the shore. She turned and looked back. In the dim greenish light, she could barely make out the white spot of her clothes, the round, black shape of her guide crouching patiently beside it. The water pushed up against the shore, as if searching for her, and she stepped farther away from it, warily peering in the dim light for some sign of the Hag.

She thought she heard a chuckle, and she whipped around, but it was only the insistent lap of the water against the stone. She drew herself up, and opened her arms as wide as her shaking body would let her. “Great Herne,” she whispered, “if ever you were with me, be with me now.” She drew a deep breath and cried, into the thick and chilly air, “Great Hag! Great Hag, come forth upon my call.” The rock was slick beneath her soles, and she felt something slice through her feet as she took a single step forward. She cried out and nearly lost her balance. She looked down and saw that unlike the opposite shore, these boulders were punctuated by shards of what looked like glass. She squatted down, watching her pale blood roll down the slope into the sea, carefully feeling all around her for smooth places between the razor-edged outcroppings. She edged forward, feeling her way with questing hands and careful feet. But for all her care, the jagged edges sliced unmercifully and she nearly fell more than once. At last she reached a relatively smooth plateau, beside the cluster of boulders that rose from the center of the island like the throne of the Goblin King in his stinking hall.

“Great Hag,” she whispered, scarcely daring to give the words voice. “Great Hag, come forth and heed your child’s plea.” Her voice echoed up and around and down the vault of the ceiling, sighing and rippling across the water, and she saw the depths dull to dark green as the drifting shadows within it seemed to thicken in response. It was as if everything about her in some way was so intimately connected to the place that every move she made, every breath she drew, every thought, even, had some effect. “Great Hag,” she whispered, this time pouring every ounce of need, of desire, of hope she possessed into the words. “Come forth.”

But the boulders were silent and the sea was still.

Vinaver sank shaking to her haunches, her arms wrapped around her knees. Her guide was wrong, so obviously wrong. And she was so stupid, so obviously stupid to have trusted him—it. What could she have expected from a blind, deaf, voiceless, practically senseless creature? What could she have expected from the foul misshapen things that led her to it? Tears filled her eyes and spilled down her cheeks, seeping down her fingers, rolling down her arms unheeded. Was all of this for naught? Had she truly come here to the underbelly of the world to find nothing? She would not survive another swim back across that swarming sea. She had failed. Faerie would disintegrate, Finuviel, her fair son, so bright with promise, would die the true death, and all the great and shining beauty that was Faerie would go down into nothingness. Down here, she thought, into this primal soup. There was nothing else to do but wait for it.

She rested her cheek on her knees, and in the soft and swirling mist, wooing as a lover’s whisper, she thought she heard a snatch of music, clear and airy and piping as any ever drifted across a Faerie meadow. A woman’s voice danced through her mind, low and mocking. “A queen who’s never a queen to be—is that who comes to call on me?”

Slowly Vinaver rose to her feet, forcing herself to straighten, as a sudden fear greater than any she had yet known gripped her like a vise. “Great Hag?” she whispered, for the voice was not that of an old woman. Scarcely daring to believe that here, at last, was the end of all her striving, she peered into the darkness, gaping in astonishment as the boulders lifted and shifted and finally resolved themselves into the hideous visage of an old woman hunching over a great black cauldron. The cauldron was balanced over a firepit by a curious arrangement of two polished crystal globes, and a makeshift tripod of iron legs beneath a flat disk where a third globe should have been.

As Vinaver stared in horror, steam spiraled up from the depths of the cauldron, half obscuring the grinning, toothless rictus on the Hag’s gray-blue face, which was striated with wrinkled folds carved like channels into the bedrock of her sunken eyes and cheeks. She gripped what looked like a thick branch—for a few dead leaves still clung to it—in two clawlike hands as she stirred her brew.

The Hag’s bright eyes fixed on her, and Vinaver gasped. Like Herne’s, glowing red then green, they pierced her with a force that made her stagger. She regained her footing and took a single step forward, forgetful of the sharp crystals that slashed her feet to the bones, and cried out as the pain lanced up her leg. As more of her pale blood leaked into the rock, it shuddered beneath her feet, smoothing itself beneath her bleeding soles. And she understood she was to draw closer.

Each step was agony but she refused to flinch. She had come so far. She could go a little farther, after all. There was neither kindness nor cruelty in that glittering green gaze, just a hungry interest. The Hag’s gray tongue flicked over her yellowed and blackened teeth and for a moment her eyes turned red.

Suddenly more frightened than ever, Vinaver paused. Such was the nature of the Hag, Vinaver understood with sudden insight, she who destroys that all might be made new. Everything was fodder for her cauldron, grist for her mill, silt for her sea. Vinaver wanted to speak, but something that felt like her heart blocked her throat. She saw more clearly the improvised contrivance that supported the cauldron in place of a third globe. It was of iron—three cast-iron legs bound into a tripod, a small disk placed on top. And suddenly, with cold and certain knowing, she knew exactly where the third globe was.

“The moonstone,” she whispered, daring to meet the Hag’s eyes. “The moonstone globe—the one that wears the Caul within my sister’s Palace—that moonstone globe is yours.”

The Hag hissed, her rheumy eyes darting from side to side. She gave a great turn to the stick and the steam rose and swirled and in the depths, Vinaver thought she saw a familiar face—a furtive face that turned his back and threw a robe over his head before the image dissipated into nothing.

“Timias,” Vinaver whispered, recognizing her mother’s Chief Councilor and perpetual thorn in her side. “’Twas Timias who took your globe?” Another hiss was the only sound the Hag made as she swung her shoulders in a mighty arc as she gave the cauldron another stir. A shiver ran through Vinaver. She looked down at the other two globes, this time more carefully, and saw that one gleamed black as pitch in the bluish glow of the unnatural fire that burned within the stone pit beneath the cauldron, and that the other was flecked with specks of black, white, green and red. And suddenly, in a flash of insight, Vinaver understood something of the nature of the problem. The black globe—the goblins, perhaps. The other, the mortals, most like. And the missing moonstone that Timias had apparently stolen in some way represented Faerie. It WAS Faerie, Vinaver realized. And Timias had taken it from the Hag. She had always wondered why the stories were so vague about the origination of the globe. “The trees have told me that Faerie is dying. I see that your globe is—is missing.” These two were connected in some way, she was sure of it. She hesitated, attempting to gauge the thoughts behind the creature’s burning eyes. And then she gathered her courage and spoke quickly, lest she lose her resolve. “I know there’s something terribly wrong for Alemandine is unable to conceive her Heir. And the trees told me to come to you, Great Hag, that you would know how to save Faerie.” Vinaver finished quickly, for there was something in the Hag’s eyes that made her want to run into the water, to give herself up to those sultry depths, to the peace the green sea promised.

The steam rose up in a high cloud as the Hag stirred the cauldron. She said nothing, but the same mocking voice Vinaver heard before swirled out of the steam, the words carried on the vapor. “Round about the circle goes, dark to light and back it flows—world without end can never be, so says every prophecy.”

“But what do you say?” asked Vinaver, suddenly brave with the courage of desperation. What, after all, did she have to lose? She had no chance of going back without the Hag’s help. If she were only fodder for the Hag’s eternal soup, so be it. “What do you say, Great Mother?” Something made the Hag look up. She fixed Vinaver with that cold unforgiving stare, but Vinaver refused to shrink. She took one step forward. “Must it end now?”

The rocks groaned, as though shuddering beneath the weight of some eternal sorrow, and the Hag’s appearance rippled, shifting from the hungry visage of She Who Destroys to the drawn and ravaged face of She Who Mourns. Suddenly she did not seem at all malevolent. Her shoulders collapsed, leaving her stooped and frail, and her face thinned and the reddish light in the green depths died. Her lipless mouth twisted and a tear seeped down one ruined cheek.

Time hung, suspended, the moment prolonged beyond all reality. The darkness seemed to shrink, expand, then retreat once more, as a light, white and clean as springtime sun leaped up from the cauldron’s depths. And in that radiant flash, Vinaver thought she saw the Hag transformed, her craggy features melting, dissolving, her flesh rounding and firming and lifting, flushing to a gentle shade of pink, and her eyes faded to violet. The Maiden, she thought. But even as Vinaver recognized the transformation, it faded away, dispersing into the air like one of the squirming things roaming the water’s depths. Finally it was Vinaver who broke the spell. “I think I understand,” she whispered. “You can’t change. Something’s happened. And you can’t change.” The rage that flared from the Hag’s red eyes gave Vinaver her first real thread of hope. “Tell me,” she whispered. “Make me understand. If I should be the Queen, why am I not? Why can you not become the Maiden, and why did Timias take your globe? What is it that’s killing Faerie, and how do I make it stop?”

Vinaver thought at first the Hag would not answer her at all, for the creature only shifted from side to side, and she wondered if the Hag was incapable of speech. After all, Herne had never spoken to her, in their encounter. But in a smooth motion that belied the image of the ancient crone, the Hag suddenly turned to face Vinaver and shrieked, in a voice that echoed across the vaulted space like the harsh cry of a crow, “Why? Why? Why?”

Perplexed, Vinaver stared. “Why what?”

With another shriek, the Hag went back to her stirring and the steam billowed up in great white clouds, wreathing and obscuring her face. For a moment, Vinaver was afraid the Hag would disappear. But as the steam cleared, she was still there, bright green eyes fixed on Vinaver. “Why should I help you?”

It was not a question Vinaver expected and the Hag’s voice alone unsettled her, grating on her ears like a blade scraped over stone. She cast about, taken aback, momentarily confused. What could she possibly say that would convince the Hag that Faerie should be saved? What part was more beautiful than the rest? Where to even begin?

And then Finuviel’s face rose before her, his form danced out of her memory, the tiny infant, delicately made, but sturdy, so fair and strong and merry as he grew, the epitome of what a prince of the sidhe should be. She remembered the first time she’d heard his laugh. A butterfly had landed on his toes. Her eyes clouded with tears and her throat thickened. “Well,” she said at last. “I have a son.”

“Ah,” sighed the Hag, and with a stir of her stick, the great cauldron released another cloud of steam. This time it resolved itself into the angular, antlered face of Herne, the Lord of the Forest and the Wild Hunt.

“You know—you know about my son?” Vinaver said. For the appearance of Herne’s image implied that the Hag knew he’d fathered Finuviel. No one else had ever believed Vinaver. Everyone accused her of using the claim of Herne as a way of concealing Finuviel’s true parentage. The enormity of the Hag’s knowledge burst like a sunrise into her mind and suddenly Vinaver believed that not only was there hope, but that the Hag would help her.

Without another sound, the Hag beckoned. Vinaver crept forward, wincing on her ruined feet, her heart pounding audibly. At the edge of the firepit, just before it was possible for Vinaver to see inside the cauldron, she held up her hand. “Yes,” the Hag whispered, a long, low croon that tickled the back of Vinaver’s neck like the barest stroke of her long sharp claws. “Yes, I know about your son. I know all about your son. And yes, for his sake, and for his father’s, I shall help you. But there is always a price, and so I ask you, Vinaver Tree-speaker, the would-be, should-be Queen—tell me, what will you pay for the knowledge of the Hag?”

“What would you have of me?” The water was still dripping off her hair. It ran in chilly rivulets down her back, between the cleft of her buttocks, trickling down her legs to drip off the two swollen lumps of throbbing flesh that were her bloodied feet. She felt as if she stood in a pool of her own congealing blood. The cold air raised gooseflesh on her entire body, but an act of will greater than any she had ever known she was capable of kept her upright and still. She had come so far and searched for so long that she had nothing left but the rags on her back. What could the Hag possibly want of her?

“There are three things.” The whisper rasped down her spine like a fingernail across granite. “For the first, I want my globe back. For the second, I want the head of him that took it from me.”

At that, Vinaver’s head snapped up. “Timias?”

This time she was standing far too close when the angry light flared in the Hag’s eyes. A searing pain lanced up her leg as she involuntarily stepped back onto a sharp edge, while an image blazed clearly in her mind, the image of Timias creeping away from the cavern, bearing the moonstone globe. “You want me to kill Timias?”

“His life is mine, and my cauldron wants his head.” The Hag’s hiss, her narrowed eyes, reminded Vinaver of a snake. “Cut off his head with a silvered edge, and give it to me for my cauldron. So those are the first two things I want of you. Will you agree?”

The depth of the hatred in the Hag’s voice frightened Vinaver. “All right.” She had no idea how she would actually fulfill the second requirement—for to do what the Hag asked required some forethought. And it had not occurred to her that murder would be involved. Vinaver swallowed hard. “What’s the third?”

This time the Hag’s response was a sinister chuckle. She leaned forward, even as Vinaver instinctively shrank back. “The third is the most important and the most necessary. I want your womb.”

At first Vinaver was sure she had not heard correctly, even as her hands clasped her belly. So she could only stare while the Hag chuckled with anticipatory glee. “What?”

“I need your womb.”

Vinaver looked at the scaly gray claws that gripped the stick, recoiling at the idea of those twisted, thickened digits anywhere near her flesh. “Why?” she whispered, horrified.

The Hag’s laugh was like the rumble of rocks down a hillside. “Ah, little queen. Already the circle widens into a spiral. The spiral turns, the center loosens, and soon all will spin away, down, into my cauldron. And my cauldron must not be cheated. If you would undo what has been done, you must feed it. And that’s what it wants. That’s what it needs. That’s what it craves.” She drew out the last long syllable, beckoning Vinaver closer with a crooked, yellow claw. “Come, if you will, and look within—but feed the cauldron to stop the spin.” She stirred the stick, swaying a little, eyes closed as she chanted. Suddenly she stopped and opened her eyes. “You want your sister pregnant with Faerie’s heir? Give me your womb. That’s how it has to work, I’m afraid.”

Vinaver swallowed hard, trying to control the beating of her heart. The monstrous thing muttered as she stirred, her lumpen shape rolling in slow motion in a large, left-turning spiral. Left-turning, Vinaver thought, the direction of breakdown, banishment and change, and in that moment she understood. As the Hag stirred the cauldron, so the tide of Faerie swung. Turning it to the left meant the undoing of the world. “Stop that!” cried Vinaver. “You’re doing it—stop it—”

The Hag jerked around, the hairs on the end of her nose twitching, as if she smelled Vinaver’s desperation. “Round about the circle goes, dark to light and back it flows,” she chanted, as if Vinaver had not spoken. “She that dares to stop my spin, had better put a tidbit in. Feed my cauldron, pay the price, lest all be lost when light turns dark and dark turns light.”

Vinaver’s stomach clenched and her gut heaved at the thought that that creature might touch her. But she had come all this way, and what need had she of a womb, after all? She’d borne a son in her appointed time, such as it was. What did it matter whether or not she gave up her womb? “But—but if I give you my womb,” she whispered, “will it not mean I can never be Queen?” The Hag threw back her head and howled as if at some unwitting joke, but Vinaver would not be dissuaded. “Tell me—tell me what I shall become—if I give you this—this part of me. If I shall not be Queen, what then?”

“She who comes with bitter need, had better then my cauldron feed.”

But suddenly, Vinaver understood something that had eluded her for a long time. She had never understood why the god had come to her that Beltane night when Finuviel was conceived. No one had believed her. But the Hag knew. Her womb had served its purpose. “All right,” she shrugged. “Done.”

The Hag cackled. Vinaver’s mouth dried up like a desert, and she thought she might faint as nausea flopped in her gut like a dying fish. The Hag’s claws closed around her wrist, drawing her closer, and the Hag’s face seemed to fill her entire field of vision. The Hag’s eyes glittered red, then green in the leaping blue flames, and her craggy face dissolved into unrecognizable chaos. Vinaver collapsed, crying out as she felt the scratch of the Hag’s cold fingers, pulling at her clothing, kneading at her flesh, creeping between her legs, probing for the opening to the very center of her self, seeking, separating, pushing in with sharp, grasping claws.

Vinaver cried out at the first stab of blinding pain, and she pushed away, but the Hag held her hard. She shut her eyes as the pain flamed through her, and a kaleidoscope of voices and faces exploded in her mind, uncurling like ribbons, in long slow swirls of scarlet agony. She heard the wet, sucking rent, as her flesh ripped, but she didn’t care, because she understood at last that it was in the pain that the Hag imparted her knowledge. As her body broke and bled, her mind opened, and a torrent of images cascaded in. She saw her mother, Timias and the mortal by whose hand the Caul was forged. She saw the moment of its making, when the three called down the magic and bound the two worlds—Shadow and Faerie—inextricably together, tightening the normal bonds between them tight as a noose.

In some detached corner of her mind, she felt the Hag tear away her womb, felt the hot gush of blood between her thighs, and she lay flat, legs thrown open, dazed and helpless as a newborn child. The pictures shuddered, swirled, spun and split into a double set of likenesses—somehow at once both that which was, and that which should have been. She saw herself born the sole daughter of Gloriana, Faerie’s great Queen, named her Heir, and made Queen when Gloriana went into the West. She saw a Faerie green and flourishing, Finuviel born in the fullness of time, welcomed as the new King of Faerie, even while, running concurrently, like the overlay of the Shadowlands on Faerie, she saw what had really happened since the forging of the Caul. And then, as the pain settled into a slow throb, she saw faint and pale the images of what might be. She lay back, eyes open, staring into the vaulted ceiling as the ghostly outlines formed and reformed, and the world slowly dissolved into nothingness.

When next she opened her eyes, she was lying flat on her back still, staring up at what she first thought to be pinpoints of twinkling lichen. Then a warm wind rustled through the branches of the trees above her, and she realized that the soft grass beneath her was slick with morning dew. And as she watched through eyes suddenly flooded with tears, the black sky above her brightened to gray as the first light of a Faerie dawn broke the horizon at last.

1

The gremlin’s howls filled the forest. Like an avalanche, like a tidal wave, the sounds of rage and anguish and despair too long checked, exploded through the silent Samhain night, unleashed in earsplitting shrieks that continued unabated far beyond the physical capacity of such a small being to sustain such unbroken cacophony. Delphinea crumpled to her knees, crumbling like a dam against a sudden thaw, and pressed her head against the horse’s side, trying to stifle the wails that wrapped themselves around her, first like water, then like wool, nearly choking her, crushing her with their weight of unadulterated sorrow, anger and need. The moon was hidden and the still sky was only illuminated by silver starlight. The night condensed into nothing but the blood-wrenching screams and the slick salt smell of the horse’s coarse hair beneath her cheek. She felt subtle tremors beneath the surface of the leaf-strewn ground as if the great trees all around them shuddered to their roots. The horse trembled and shook, and Delphinea wrapped her arms as best she could around the animal’s neck, murmuring a gentle croon more felt than heard, trying to create a subtle vibration to act as the only shield she could think of under such an onslaught of sound. But there was nothing, ultimately, that could stand against it, and finally, she collapsed against the horse’s side, the mare’s great beating heart her only anchor.

It was thus, curled and quivering, that Vinaver’s house guards found her shortly before dawn, palms plastered against her ears, the horse only semi-aware, its eyes rolled back, its ears flattened against its head. Petri’s cries showed no signs of diminishing. The orange torchlight revealed the gremlin flopping on the forest floor like a fish caught in a net. As he is, mused Delphinea, within a net of Samhain madness. Every Samhain the gremlins all went mad, and usually they were confined. But nothing seemed to be happening quite the way it usually did.

It took all six guards to overpower him, despite the fact that he was less than half the size of Delphinea. Even the thick gag they improvised from a strip of hastily cutoff doublet sleeve barely stifled Petri’s cries. When at last Petri was subdued, his howling reduced to smothered moans, they turned their attention to Delphinea, sitting quiet and disheveled beside the near-insensible horse.

“My lady?” The dark-haired sidhe who bent over her wore a gold breastplate emblazoned with the Queen’s crest, and for a moment, Delphinea was afraid the soldiers had been sent out by the Queen and Timias to drag both of them back to the palace under arrest. She scrambled backward, as the flickering torchlight gleamed on the officer’s insignia embroidered on his sleeves. But his next words made her nearly weep with relief. “The Lady Vinaver sent us out to find you. I am Ethoniel, a captain in the Third Company of Her Majesty’s Knights. If you would be so kind as to come with us, we will escort you to her Forest House.”

“How’d that thing get out?” asked one of the other soldiers, with a jerk of his thumb over his shoulder in Petri’s direction.

“Petri is not a thing,” she sputtered, even as the captain extended his hand and helped her to stand. Two of the others coaxed her mare onto her feet.

“We’ll take you both.” The captain spoke firmly. “It doesn’t look as if it’ll give us any trouble now. We can’t leave it here.” Indeed, Petri lay in a forlorn little heap, his arms bound to his sides, one leathery little cheek pressed to the pine needles and leaves that carpeted the forest floor, eyes closed, breathing hard, but every other muscle relaxed. “Forgive me for taking the time to ask you, lady, but how did this happen? Did it follow you, my lady? How did it get past the gates?”

She knew that for any other sidhe, the presence of a gremlin leagues away from the palace of the Queen of Faerie, the one place to which they were forever bound, at least according to all the lore, was surprising to the point of shocking. But how to explain to them that despite his incipient madness, it was Petri who’d guided her through the maze of the ancient forest, close enough to Vinaver’s house that they could be rescued? Surely Vinaver, herself outcast by the Court, would understand that Delphinea could not leave the loyal little gremlin behind, for it was abundantly clear that Timias and the Queen intended to lay at least part of the responsibility for the missing Caul on the entire gremlin population. But now was not the time to explain how or why the gremlin was with her. For, if it were possible, there was something even more unnatural within the forest, something she knew these soldiers must see for themselves to believe.

The torchlight illuminated the clearing, but it was not just the broken branches and torn undergrowth alone that made her certain of the direction in which to lead the guards. “The magic weakens as the Queen’s pregnancy advances, Captain.” Surely that explanation would have to suffice. “But I have to show you something,” she said. “Please come?” She gathered up her riding skirts and set off, without waiting to see if they followed or not. It was like a smell, she thought, a foul, ripe rot that led her with unerring instinct back through the thick wood. Once, she put her hand on a trunk to steady herself and was disturbed to feel a tremor beneath the bark, and a sharp sting shot up her arm. The branches dipped low, with a little moaning sigh, and for a moment, Delphinea thought she heard a whispered voice. She startled back, but the captain was at her elbow, the torch sending long shadows across his face.

“Where are we going, lady?”

For a moment, she was too puzzled by this sense of communication with the trees to answer the question, for she had never before felt any particular connection to the trees of Faerie. Indeed, in the high mountains of her homeland, trees such as these primeval oaks and ashes were rare. “This way,” was all she could say. And with a sense as certain as it was unexplainable, she led the grim-faced guards through the forest, to where the slaughtered host of the sidhe lay in heaps beside their dead horses and golden arms that gleamed like water in the gray dawn.

The guards gathered around Delphinea in shocked and silent horror, surveying the carnage. The corpses lay like discarded mannequins after a masque, armor all askew, swords and spears and broken arrows sticking up in all directions like bent matchsticks, impotent as mortal weapons. A mist floated over all, and from far away Delphinea could hear the rush of water. Without warning, a banner stirred and flapped on its staff, blown by a ghostly breeze that whispered through the trees, and as the mist moved over the remains, it seemed for one moment, the host might rise, laughing and whole. The captain raised his torch and Alemandine’s colors—indigo and violet and blue on gold-edged white—flashed against the backdrop of the black trees.

They spoke behind her, in hushed and disbelieving whispers. “Can this be the—”

“Are they the—”

“Is this really our—”

“These are our comrades,” interrupted the captain, answering all. There was a long silence, then he continued, in a voice heavy with loss, “You see, my lady, we, too, should have been among their company. But Prince Finuviel ordered us to stay and guard his mother’s house.”

“What could have done this?” another murmured.

“Who could have done this?” put in a third.

Delphinea could feel them tensing all around her, shuffling their feet, skittish as horses at the smell of blood. The captain bent down, holding his flaming torch a scant foot or so above the nearest corpse. He turned the body over. The face of the dead sidhe was calm, pale, and it crumpled into powder, finer than sand, as the light fell upon it. He ran the torch down the armor, to the insignia, the sword, and spurs the knight wore. A dark slash ran diagonally across the golden breastplate, where the metal itself was scarred and shriveled, as if burnt away to ash. “Silver,” he said after a long pause. He shut the empty helm and rose to his feet. “They’ve died the true death. They’ll be gone when the sunlight hits them.”

“So this is the host, then, that was called up to reinforce our borders? The host the minstrels sing of, in Alemandine’s Court?” She had missed the glorious parade by scant hours, arriving from the mountains too late. A chill ran through her that had nothing to do with the temperature of the air. She wrapped her arms around herself, feeling cold all over. Now she would remember all too well forever this last sight of them.

“That’s exactly who they appear to be, my lady.” The captain handed his torch to one of the others and gestured at his men. “Fan out. We’ll have to come back when it’s light, but let’s see as much as we can now.”

While the bodies are still intact. The chilling thought ran through her mind. But she said nothing, and he continued, “Look for His Grace. Look for the Prince. It’s the first question the Lady Vinaver will ask.” His voice faltered and broke, and Delphinea was struck once again by how much Finuviel seemed to be loved by everyone who knew him. She had begun to suspect that his was the face that haunted the visions that came to her while she slept—the visions mortals called “dreams.” The sidhe didn’t dream. At least, all the others didn’t. But lately the phantoms that haunted her sleep came more frequently, and she was no longer able to ignore them. She had come to Court hoping that someone there could explain them to her, and reassure her, perhaps, that this was not as unheard of as she was afraid it was. She had been afraid to mention them to anyone at all, but she had resolved to tell Vinaver, if she ever had the chance. She didn’t want to think how Vinaver would react to the news that the army her son led had been slaughtered and that her son himself was missing.

For if the minstrels sang sweetly of the hosting of the sidhe, it was nothing to the songs they sang about Finuviel. Finuviel was the “shining one,” loved by all who knew him, claimed by his mother to have been fathered by the great god Herne himself one Beltane. Although everyone dismissed Vinaver’s claim as a pathetic attempt to gain some place for herself at the Court, it was universally acknowledged that Finuviel, whoever his father had been, was the epitome of every grace, and the master of every art. Even those who scorned Vinaver publicly spoke highly of Finuviel, and it was Finuviel that Vinaver and a small group of councilors conspired to place upon the throne of Faerie in the sick Queen’s stead. What would they do, if Finuviel were lost?

But he’s not. The knowledge rose from someplace deep inside her, a small voice that spoke with such silent authority, she felt immediately calmed, although she did not understand either how she knew such a thing, or why she should trust such knowledge. All she knew was that she did. She watched the torches bob up and down across the field as the soldiers wove through the heaps of the dead. At last the captain waved them all back. “Well?”

“We don’t see him, sir,” answered the first to reach the perimeter.

“But it appears that every last one of them was slain. There’s no one of the entire host left, except for us?” The second soldier’s brow was drawn, his mouth tight and grim.

“We should take the lady to Her Grace,” interjected a third. “She has done her duty by bringing us to this terrible place, and we have not yet discharged ours to her.”

There was a murmur of general agreement. Delphinea met the captain’s eyes. They were gray in the shadows, lighter than the gray of his doublet, gray as the pale faces of the dead sidhe beneath the graying sky. “Who could’ve done this, Captain?”

“Mortals.” He shrugged and looked around with a deep sigh. “From what I can tell, they were all killed with silver blades. Who else can wield silver in such fashion?” In the orange torchlight, his face was yellowish and gaunt.

“But why—”

He shrugged and turned away before she could finish her sentence. The sight alone defied reason. We are all sickening, she thought. The Caul must be undone or we shall all sicken and die. She turned away silently, gathering up her riding skirts, the men following. That so many should die the true death, the final death, was terrible enough. But was it really possible that mortals—mere mortals, as the lorespinners dismissed them—could have armed themselves with silver and attacked an entire host?

So much was happening, so much was changing. Round about the circle goes, dark to light and back it flows. The old nursery song spooled out of her memory. But for the first time, she had the sense that the turning wheel of time was in danger of spinning violently out of control.

By the time they reached Petri, the dawn light had strengthened enough to show him lying curled into a heavy sleep. He had stopped making any noise at all except for long shuddering snores and his mouth hung slack over the gag. She wondered how long it would take to convince Vinaver that Finuviel did not lie dead beneath the ancient trees with the others.

For Finuviel was not dead, she was quite sure of that, in an odd way she could not at all explain. Something had happened to her last night, something had changed within her, awakened in her, in some way she did not yet fully understand but knew with absolute certainty she should trust. And she knew that Finuviel was not dead. Not yet.

But these grim guards would have to see for themselves—Vinaver would require as much proof as could be had that Finuviel was not here. She would not take Delphinea’s word for it; why should she? So Delphinea said nothing as they marched back beneath the trees and it struck her that the sound of the wind in the branches was like the lowing of the cattle on the hillsides of her homeland. What wind? Her head jerked up and around, as she realized that the air was still. The captain, ever alert, held up his hand.

“Are you all right, lady?”

The curious sound stopped. She shook her head, feeling foolish. She was only overwrought, and succumbing to the rigors of the night. Best not to call attention to it. What would her mother say to do? Smile. “I but found last night somewhat taxing.”

It was as brave an attempt as she could muster at the polished language of the Court, and no lady with a lifetime’s experience at Court could have phrased it better. Half smiles bent their mouths, but melted like spring snow. How meaningless the words sounded, brittle as the drying leaves gusting at their feet, swirling at their ankles in deepening drifts. There was simply no etiquette to deal with such a loss, which must affect the soldiers doubly hard. What stroke of chance had led Finuviel to send these six back to guard his mother’s house? But why did he think it needed special guarding? How vulnerable could it be so deep within the Old Forest of Faerie? It was leagues and leagues from the goblin-infested Wastelands. Had he suspected something? Had he known that mortals armed with silver might attack?

She felt, rather than heard, a deep throbbing moan as she passed beneath the branches of a nearly leafless giant. Its great trunk divided into two armlike branches that ended in countless outstretched skeletal hands. The Wild Hunt had swept many of the trees bare. Yet the trees of Faerie had never before been bare. Their leaves turned from gold to red to russet to brown to green in one eternal round of color, and if a few fell, new ones grew to take their place, in an endless cycle of regeneration. She thought of the dust on the floor of the Caul chamber, the rust on the hinges of the huge brass doors, of the rotting bodies of her cattle and the foals, the fouled streams. Was this just another piece of evidence that Faerie was truly dying? But she was silent as she allowed the guards to help her onto her saddle. The mare seemed fully recuperated, and tossed her head and whickered a greeting as Delphinea gathered up the reins.

Petri was slung over the back of another horse like a sack of meal. Though Delphinea protested his treatment, the horse shied and whinnied and finally a blanket had to be placed beneath the gremlin and the animal before the horse could be induced to carry him.

“I cannot imagine what circumstances brought you here on such a strange, sad night, my lady.” The captain swung into his saddle, and raised his arm in the signal for the company to ride. He rode past, stern-faced and tensed, and she realized he did not expect an answer. The milk-white horses moved like wraiths beneath the black leafless branches, as a red sun rose higher in a violet-cerulean sky. Even now, stark as it was, it was beautiful, beautiful in the intensity of its pulsing radiance. The air was crisp, but heavy, charged with portent.

They rode in grim silence another half turn of a glass. The light grew stronger and suddenly, the thick wood parted, and a most extraordinary sight rose up. Like a living wall, a latticework of high hedge grew laced between the trees, and just beyond, high above the ground, within what appeared to be a grove of ancient oaks and sturdy ashes, Delphinea saw a house that looked as if it had grown out of the trees, not been built into them.

The reins slackened in her hands as she gaped, openmouthed, at the peaked roofs, all covered in shingled bark, windows laced like spiderwebs strung between the branches. Winding stairs curved up and around the thick trunks, and tiny lanterns twinkled in and among the leaf-laden branches. There is magic yet in Faerie, she thought, and was a little comforted. Her mother’s house of light and stone was nothing like this living wonder, and even Alemandine’s palace, as beautiful as its turrets of ivory and crystal were, could not compare to this house of trees.

As if he’d heard her thoughts, Ethoniel smiled. “Indeed, my lady. The Forest House of the Lady Vinaver is a wonder in which all Faerie should delight, not shun.” He held up his hand and the company slowed their mounts to a walk all around her. He leaned over and touched her forearm. “Slowly, lady. Do you not see the danger that grows within the hedge?”

As they came closer, she saw that the hedge was full of jagged thorns, skinny as needles, some as long as her fingers, with tiny barbs at their ends which would make them doubly difficult to remove, all twined about with pale white flowers that put out such a delicate scent that Delphinea had to force herself not to push her nose into the hedge’s depths, to drink more deeply of it. She realized that the plant was nourished by the blood of things that impaled themselves upon the thorns, and from the profusion of flowers, the thickness of the vines, and the lushness of the scent, there were plenty of creatures that did. She shuddered as she rode through the narrow archway that formed the only gate, shrinking away from what was at once so beautiful, and so deadly, so tempting, and so dangerous.

Only one leather-clad attendant came forward, slipping out from a set of doors within the great trunk of an enormous tree, and Delphinea wondered once again why Finuviel had diverted any number of his host at all to guard Vinaver’s house. Secluded as it was within the heart of the Great Forest, and surrounded by the high hedge of bloodthirsty thorns, it appeared not at all vulnerable, except perhaps to a direct goblin attack. But was such a thing likely? From the talk of the Court, she had surmised that the war was expected to be fought on the borders of the Wastelands, not within the very heart of Faerie itself.

But the fact that Finuviel had regard for his mother’s safety made her like him, too, and she wondered if she was falling under the spell of his reputation. She followed the captain of the guard inside the house, trying not to gawk at the golden grace of the polished staircase that flowed seamlessly around the giant central oak forming the main pillar of this part of the house. From certain angles, the staircase was invisible; from others, it was the focal point that drew the eye up and into the leafy canopy forming the roof. She kilted up her skirts and followed the men up the steps, trying not to trip as the golden radiance filtered down, soothing and nourishing as new milk. She closed her eyes, her feet moving in some unconscious synchrony, bathing in the incandescence, forgetting for a moment the dire news they bore. There was only the warmth and the light. On and on, up and up, she climbed, and the face that filled her vision against the backdrop of rosy light was framed with coal-black curls. But instead of smiling, the face contorted in agony and Delphinea gasped, opened her eyes and tripped.

“Watch your step, my lady,” growled the guard who had Petri, by this time in a dead stupor, slung across his back.

Still groggy from the vision, Delphinea could only murmur. It was bad enough that the dreams came while she slept. If she was going to start having them while she was awake, she would have to talk to someone about them. Vinaver, hopefully.

But as they reached an upper landing, Ethoniel paused before a door and turned to Delphinea. “You’ve had a harrowing night, my lady. This may be somewhat difficult. I don’t expect Lady Vinaver will welcome this news.”

“But I want her to know I’m here—maybe there’s something I can do—” Maybe she will believe me if I tell her Finuviel is alive. But she left the last unspoken, and looked at him with mute appeal.

He looked dubious, but shrugged. “As you wish, my lady. The Lady Vinaver is given to some unexpected reactions on occasion. Beware.” He knocked on the door, and opening it, stepped inside an antechamber. He motioned Delphinea, and the guard carrying Petri inside, then knocked on the inner door. Vinaver herself opened the door.

All potential greetings died in Delphinea’s throat as the expression on Vinaver’s face changed from one of welcome to one of horrified disbelief at Ethoniel’s quick report. She had only stared at him, her eyes glowing with a terrible green fire in her suddenly white and flame-red face. Delphinea thought Vinaver might faint, and she wondered if it was that for which Ethoniel had sought to prepare her.

But nothing could’ve prepared Delphinea for the sight of Vinaver’s collapse, for she fell to her knees in a brittle crunch of bone, as the framework of her wings splintered like icicles. And as Delphinea watched in horror, the wings sheared away completely, the tissues tearing with the wet sound of splitting skin, leaving twin fountains of pale blood arcing from Vinaver’s shoulder blades.

She could think of nothing to say or do, for nothing but intuition made her sure that Finuviel was not dead. Not yet. And in that moment Delphinea understood that if anything really did happen to Finuviel, the consequences would be far more terrible than anything she had yet imagined.

As if from very far away, Delphinea heard Ethoniel bellow for Vinaver’s attendants, saw a very dark and burly stranger rise from a chair beside the fireplace and point in her direction. She felt the room suddenly grow very hot and very crowded, as more guards and attendants rushed in. Vinaver’s blood was flowing over her shoulders like a cloak, running in great waves down her arms, dripping off her fingers, soaking the fabric of the back of her gown. The captain turned on his heel, brushing past her, and she felt strong arms ease her off her feet, as the world finally, mercifully, went dark.

When next she opened her eyes, she was lying on a low couch in the little antechamber of Vinaver’s bower. The door to the inner room was closed. The couch had been placed next to a polished hearth in which a small fire burned. A basket of bread and cheese and apples had been placed beside her, and a tall goblet, filled with something clear that smelled sweet, stood beside a covered posset-cup on a wooden tray. A drone worthy of a beehive rose from the floor beside her. She looked down. It was Petri, lying curled up on a red hearth rug, in a round patch of sunlight, his head on a small pillow, sound asleep. Poor little thing, she thought. If her ordeal had been bad, his was surely worse.

“How d’you feel?”

She bolted straight up at the unexpected voice. It belonged to the big dark stranger she’d noticed in Vinaver’s bower before. He was sitting on the opposite side of the hearth, and she knew instantly what had drawn her attention, even amidst those few terrible moments in Vinaver’s presence. He was mortal.

It was so obviously apparent she did not question how she knew. He looked faintly ridiculous, for the stool on which he hunched was much too low for his long legs. He wore a simple fir-green robe of fine-spun wool, over a pair of baggy trews which from their rough and ragged appearance she assumed were of mortal make. The skin of his bare legs and feet poking out from the bottoms of the trews was bluish white, covered by a sparser pelt of the same coarse black hair that curled across his face. She wondered, with a little shock, if it were possible that Vinaver kept the mortal as a pet, just as in the songs the milkmaids sang, of moon-mazed mortals lost in Faerie, willing slaves to the sidhe. Her mother did not consider such tales seemly and scorned all talk of mortals. Delphinea had never imagined she would meet one, so she examined him with unabashed curiosity.

It was midmorning or later, and the light streamed down through windows set within the upper branches of the trees, filling the room with a brittle brilliance, casting strong shadows on the mortal’s dark face. He must be old, she thought, very old, even as mortals counted years, for his dark hair was shot through in most places with broad swaths of gray and white and his skin was grayish and hung off his face. Deep lines ran from the inner corners of his eyes, all the way past the outer corners of his mouth. His eyes burned with such intensity there was no other color they could be but black.

A tremor ran through her as her eyes locked with his, for it seemed that within those depths lay some knowledge that she not even yet imagined, coupled with pain, a lot of pain. His forehead gleamed with sweat, and as he raised his arm to mop his brow with a linen kerchief, she caught a glimpse of a white bandage, stark against his skin, beneath the vivid green. But his eyes were like twin beacons burning through a storm, and she realized that whatever the source of his pain, he wasn’t afraid of it.

She felt drawn to his solid strength, sensing that he was strong in a way that nothing of Faerie could ever be. His essence was all earth and water, unlike the sidhe, who were manifestations of light and air. One corner of his mouth lifted in the slightest hint of a smile. “You put me in mind of my daughter, sidhe-leen. All big eyes and innocence.” He closed his eyes, and winced as if in pain, then opened them. “I’m Dougal,” he said. “What do they call you?”

Delphinea paused, uncertain how to address him. Meeting a mortal was one of the many recent events her mother had failed to foresee. But the way he looked at her, as if she were a skittish filly, calmed her for some reason she did not understand, and for a moment, at least, she felt comforted. The Samhain sun had risen on a world utterly different from the one on which it had set, and in this upside-down, topsy-turvy world, time suddenly had new meaning. Was it only yesterday that Delphinea had awakened in her bed within the palace of the Faerie Queen? So much had happened—the complete control of the Queen Timias had been able to achieve, and subsequent arrest of all the Queen’s Council, her own escape with Petri, their flight into the ancient Forest and the Wild Hunt that had nearly overrun them, even Petri’s madness, was yet nothing compared to the discovery of the decimated host and the sight of Vinaver’s collapse. Nothing and no one were quite what they appeared; no one and nothing were what she had been prepared to expect. Was it possible this mortal was involved in the whole confused plot? She wasn’t at all sure how to answer the question. “My name is Delphinea,” she said at last. “Will the Lady Vinaver be all right?”

He shrugged and folded his arms across his chest carefully. “Don’t know yet. No one’s come out of there—” he bent his head forward to indicate the closed bower door, then jerked it backward, toward the outer door “—and no one’s come through there since the guard went out to see what’s what.”

She cocked her head, considering. He didn’t sound quite the way she’d imagined a moon-mazed mortal would, and his weary, battered appearance certainly didn’t fit the flowery descriptions of them, either. “May I—may I be so curious as to inquire exactly how it happens that you have come to be here, Sir Dougal?”

At that his smile reached his eyes. “Pretty speech, sidhe-leen. I’m no one’s sir. In my world, I’m a blacksmith. And in this one, too, more’s the pity.” He broke off and the smile was gone. Far from being enchanted, he seemed quite vexed.

“You don’t seem very happy to be here.”

He laughed so hard his shoulders shook, and a whiplash of pain made him clutch his arm. “And that surprises you, does it?” What amazed her more was that he could laugh in spite of everything. But maybe, being mortal, he didn’t really understand what was happening. He sagged, sighed and shook his head. “You’re right, though. There’re many, many places I would much rather be. But that doesn’t answer your question, does it?” He indicated his arm with another jerk of his head. “Met up with a goblin. Woke up on this side of the border. She found me, brought me here. Here I am.”

“The Lady Vinaver healed you?”

“For a price, of course she did.” His mouth turned down in a bitter twist and for a moment, she thought he might say something more. But he only drew a long, careful breath and let it out slowly. Finally he looked at her. “What sort of sidhe are you, anyway?”

There was a long silence while Delphinea, completely taken aback, cast about for some sort of appropriate response. Surely he wasn’t inquiring about her ancestry? He seemed to imply there was something different about her, and she raised her chin, determined not to let a mortal get the best of her, when he leaned forward and caught her gaze with a twinkle. “But the world’s full of surprises, isn’t it? So now you tell me—what’s a small sidhe-leen like you doing traveling alone on Samhain of all nights? We heard the Wild Hunt ride past—I heard the noise that—that—thing made—”

“Petri is not a thing. He’s a gremlin.”

“Oh, is that what you call it?”

“What would you call him?”

“Hmm.” Dougal cocked his head and cradled his injured arm across his chest, as if it pained him. “Looks more like what the old stories say a trixie looks like. Brownie’s another name in some parts and my gram called them sprites. Never saw one myself. Some say they all got themselves banished from the mortal world long ago for their mischief. I say it’s a damn convenient explanation for why no one ever sees them. But whatever it is, why do you keep it naked?”

“Naked?” Delphinea blinked. She flicked her eyes over to Petri. He wore the same court livery he always wore. It was, as always, perfectly clean, although somewhat rumpled. She would have said more, but the inner door opened, and Leonine, one of Vinaver’s attendants, beckoned.

“Lady Vinaver requests you both.” The lady was gowned in a plain russet smock, and her long yellow curls were held back by a simple gold chaplet. “If you will, my lady?” She dropped a small curtsy, then rose, and indicated the open door. “Sir mortal, if you please?”

Dougal made a sound almost like a growl, and again Delphinea had the distinct impression that unlike the mortals she’d heard of, he hated everything about Faerie. But why, when everything she’d seen of Shadow—the dust, the rust, even the clothes he wore—was so coarse, so crude? He needed one hand on the mantel to pull himself up. Delphinea followed Leonine through the door and hesitated, just inside the threshold. Another attendant, this one clothed in the color of autumn wheat, slipped past them, carrying a large willow basket of stained linen.

Vinaver lay on the edge of a great bed, which incorporated a natural hollow within the tree. It was lined with silk velvet that resembled moss, draped with filmy curtains. Her usually vivid color had drained away, leaving her coppery hair dull as the rust that marred the hinges of the Caul Chamber, her narrow cheeks and shriveled lips chalky. For the first time, Delphinea saw the resemblance she bore to Alemandine. And to Timias. Great Herne, he’s her father, too. And didn’t she say he wanted her drowned at birth? She had no memory of her own father—he had gone into the West a long time ago, but her mother never failed to speak of him with anything but bemused anticipation of seeing him again.

“Leonine, bring her closer. Come here, child.” Vinaver’s voice was faint, but still sharp with innate command, and Delphinea was glad to hear Vinaver yet retained something of her determined spirit. But as the attendant gently propelled her across the polished floor, Delphinea’s eyes filled with tears when she saw Vinaver’s face more closely. “Don’t weep for me,” Vinaver said. “There’s not enough time.” Her hand plucked at Delphinea’s sleeve until she slid her warm hand into Vinaver’s cold one. Vinaver tugged weakly and Delphinea leaned over, until her face hung only a scant handspan above the older sidhe’s. It occurred to her that Vinaver appeared only marginally more lifelike than the pale faces of the dead sidhe in the starlight. “I hated those wings. I was a fool to suggest them and a fool to grow them.” She paused, as if gathering her strength, and tugged again once more, until Delphinea’s ear was practically right against her lips. Her breath was like the flutter of a butterfly’s wings. “I want you to tell me, quickly, don’t think about it, just tell me—is Finuviel dead—truly dead?”

Not yet. “Not yet.” The words rose automatically to Delphinea’s lips. All she had to do was open her mouth.

“Not yet,” Vinaver breathed. She closed her eyes, then opened them. “He didn’t come, but you did. With a gremlin of all things. Whatever possessed you?” She gripped Delphinea’s hand so tightly, Delphinea was forced to bite back a yelp of pain. “How was it ever possible you were able to bring the gremlin? And why? What on earth made you do it?”

“He saved me, my lady. He led me here. But for Petri, I might have met whatever killed that host, myself. But, m-my lady—” she faltered. Where to even begin? She didn’t understand any of it. She blurted out the first question that occurred to her. “Why do you ask me if your son still lives? I’ve never even met him. And why are you surprised that I should come? You told me yourself that my life’s in danger, and you turned out to be right. Which is why I brought Petri, for he helped me to escape.” Delphinea turned, following the movement of Vinaver’s eyes, to see Petri crouching in the doorway. “Timias intended to sequester them early. It seemed so cruel—so meaningless—”

“Timias has his reasons, child, don’t ever doubt that Timias does anything without a reason.” An ugly look flashed across Vinaver’s face. “This should not be.”

Delphinea collapsed to her knees, so that she was level with Vinaver’s face. “It seems that there are many things that should not be, my lady. Perhaps you’d better tell me what’s going on. Where’s the Caul, and where’s Finuviel, and who’s responsible for that horror in the Forest?”

But Vinaver only closed her eyes and sighed. “So many questions all at once.” She tried to shake her head a little but winced.

“I have more.”

“Tell her the truth, Vinaver.” Dougal spoke from the door. Petri sniffed at his leg like a hound at a scent, and Dougal swatted him away. “Tell her the whole truth.”

“We took the Caul,” Vinaver answered wearily, her eyes closed, her cheek flat against her pillow. “Finuviel and I, and we gave it to a mortal.”

“But why?” Delphinea rocked back on her heels in horror.

“It’s as you guessed, child. The Silver Caul is poisoning Faerie. I couldn’t tell you the truth in the palace. How was I to know you’d not go running to Timias the moment I’d left your room? We took the Caul, Finuviel and I, and he gave it to a mortal to hold in surety of the bargain.”

“What bargain?” Delphinea drew back, staring down at Vinaver in horror.

“We needed a silver dagger. Where else to get it but from the mortals?”

“You mean to kill the Queen?”

“No.” Vinaver shut her eyes once more. “I could never kill my sister.” She opened her eyes. “But, she’s not really—she’s not really my sister.” Delphinea cocked her head and sank down once more onto a low stool that Leonine had drawn up to the bed, as Vinaver continued. “Alemandine isn’t really anything at all—she’s neither sidhe nor mortal. She’s a—a residue of all the energy that was left over when the Caul was created. The male and female energy mingling in my mother’s womb was enough to create her out of ungrounded magic, magic from her union with Timias and the mortal. They didn’t consider what would happen—they didn’t understand the energies they were working with. No one ever really does, you know. If I learned nothing else from the Hag, I learned that.” She broke off and with a shaking hand pushed back a loose lock of Delphinea’s hair. “There was nothing to say that Alemandine should not be Queen. After all, she was born first. And whatever else Alemandine is, she is a part of me. So no, the intention was never to kill the Queen. Timias is the one meant to die. Timias must die, Timias will die when the Caul is destroyed. For as long as the Caul endures, so will Timias. He will never choose to go into the West. He’ll never have to.”

Delphinea glanced over her shoulder. Dougal stood in the doorway still, his arms crossed over his chest. “Philomemnon said Alemandine would die when the Caul was destroyed. Is that true?”

“I doubt she has much longer to live as it is, though yes, that is a consequence. But what would you have us do? There is no way to save both the Queen and Faerie—and to save the Queen is to ensure that we all die. What choice was there really?”

“So you made a bargain with a mortal—for the dagger. And what was your part?”

“In exchange for the dagger we promised the host—”

“The host in the Forest.”

“We knew the mortal world was in chaos. A mad king sits on the throne, the people chafe beneath the rule of his foreign Queen. The events of the Shadowlands echo Faerie and those in Faerie, Shadow. It was in our best interests to resolve the strife there—”

“Why, that’s exactly what Timias said to the Council,” Delphinea blurted. “That day in the Council—the day he came back—”

“Whatever I say of him, he’s not a fool. He understands better than anyone how tightly the worlds are bound.” Vinaver plucked restlessly at the linen pillow. “But now—” She raised her head and looked directly at Petri. “Now—”

But before she could finish, the door opened and Ethoniel hesitated on the threshold, with a flushed face, breathing hard. From somewhere far below, Delphinea heard distant shouts. They all turned and looked at him, and Vinaver moved her head weakly on the pillow, beckoning Ethoniel with a feeble wave. “What news, Captain?”

At once, Ethoniel crossed the room and went down on one knee beside the bed. “I bring both good and bad news, my lady,” he hesitated. “We found no sign of Prince Finuviel, no sign at all. We found nothing of his—neither armor, nor standard, nor horse—and all of us combed the sad remains as carefully as we could. But there is a company of knights, at least ten thirteens or more, marching on the Forest House. They are coming to arrest both you and the Lady Delphinea—” here, he turned to look at Delphinea over his shoulder “—yes, my lady, you, too, on charges of high treason and the theft of the Silver Caul. They are more than a hundred against my one squad, my lady. What would you have me do?”

Even Delphinea understood his dilemma. He likely was outranked by whoever led the guards. To defy to open the gates was treason. To disobey Finuviel’s orders to defend his mother offended honor.

For a long moment no one spoke. Then Petri hissed from the door and he scrabbled forward, his eyes cast low, his tail tucked under in perfect obeisance. In a series of quick gestures, accompanied by a few stifled hisses, he motioned, I can help you find him, great lady.

Vinaver’s eyes narrowed and she looked down at the cringing gremlin, and then up at Delphinea. “The removal of the Caul from the moonstone must’ve made it possible for him to leave.”

Petri’s eyes were huge, and he looked up at Delphinea with flared nostrils. I can help you find him, lady. I know the way through Shadow. I can find him. And the Caul.