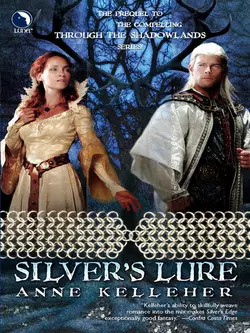

Silver′s Lure

Anne Kelleher

THROUGH THE SHADOWLANDS: Where the touch of silver was Protection, Power and Peril…THROUGH BATTLE, BLOOD AND SACRIFICE–ONLY THUS COULD THE WORLD BE SAVED…. Or so the bards sing. But at the dawning of the world, Catrione, a gifted Druid, knew only that the realms of Shadowland and Sidhe faced the gravest of danger from the goblin hordes and treacherous mortals. Now wary allies come together to wreak a spell to avert evil magicks, but the cost will be high.Much is needed to make the Silver Caul, and the songs don't speak of the price demanded. There will be duplicity and deceit, battle and blood and sacrifices–willing and unwilling.THROUGH DEATH WILL THE BALANCE OF LIFE BE PRESERVED. FOR NOW…

SELECTED PRAISE FOR

ANNE KELLEHER

“Anne Kelleher will not disappoint…[she] keeps you glued to the pages with anticipation and rewards your diligence with every word.”

—Writers Unlimited on Silver’s Bane

“Anne Kelleher has written a spellbinding work.”

—Futures Mystery Anthology Magazine on Silver’s Bane

“A stand-out fantasy/romance from this talented author.”

—FreshFiction.com on Silver’s Bane

“Silver’s Edge is a first-class fantasy.”

—In the Library Reviews

“Pure fantasy with a cutting edge.”

—Romantic Times BOOKclub on Silver’s Edge

“This book has it all…. Set aside a few hours to read this one. You will not want to put it down.”

—Writers Unlimited on Silver’s Edge

SILVER’S LURE

ANNE KELLEHER

For Donny.

Glossary of People and Places

Meeve—High Queen of Brynhyvar, Queen of Mochmorna

Briecru—her Chief Cowherd

Morla—Meeve’s twenty-seven-year-old daughter, Deirdre’s twin sister

Bran—Meeve’s fifteen-year-old son

Lochlan—Meeve’s First Knight, head of the Fiachna

Connla—Meeve’s older sister and Arch Druid (Ard-Cailleach) of all Brynhyvar

Catrione—druid and daughter of Fengus, King of Allovale

Deirdre—Meeve’s other daughter, druid

Cwynn—Meeve’s son, raised by his grandfather

Auberon—King of Faerie

Finnavar—Auberon’s mother

Loriana—Auberon’s daughter

Tatiana—Loriana’s friend

Timias/Tiermuid—Auberon’s foster brother

Macha—the Goblin Queen

Brynhyvar—the Shadowlands, inhabited by mortals and trixies, call khouri-keen by themselves and gremlins by the sidhe

Ardagh—central point in Brynhyvar

Mochmorna, Allovale, Gar and Marraghmourn—four main provinces of Brynhyvar

Lacquilea—country to the south of Brynhyvar

Eaven Morna—Meeve’s principal residence

Eaven Avellach—Fengus’s principal residence

Dalraida, Pentland—territories lying within Mochmorna and Gar, respectively

Far Nearing—peninsula on the eastern shore of Brynhyvar

White Birch Grove—druidhouse where Catrione and Deirdre live

Faerie, TirNa’lugh or the Other World—otherworldly country bound to Brynhyvar, inhabited by sidhe and goblins

Contents

Before

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Afterward

BEFORE

Below

At the bottom of the World, the Hag crouched on the jagged stone lip of her fire pit. Her face was washed with an orange glow by the crackling flames. Her breath whistled between the gaps in her teeth as she chanted, “Now the fire’s nice and hot, now’s the time to stir the pot. Take the changeling, toss it in, stir it hard and watch it spin.” She cackled softly in anticipation. Her claws skittered across the surface of the milky moonstone globe she cradled in the crook of one arm like an infant. “Make the water into stew, season it with something new, hair and bone and blood and skin, once we put the changeling in, boil brew and fire burn and dark to light will then return…” Her voice trailed off, but her words continued to echo off the lichen-lit vault above her.

She was waiting for Herne to bring her the changeling whose birth had turned her from Mother into Hag. The birth of her first offspring, the goblins, had turned her from Maiden into Mother. Mortals and sidhe had followed, but it was the last birth that signaled a turning of the Wheel in the Worlds above. The mortals, bless them, would react like ants dispossessed of their hill, the sidhe—who alone would know what was happening—would shake their heads at the mortals’ antics and the khouri-keen would burrow deep into their dens beneath the surface, only emerging when all was renewed. But the goblins—they would see it as the opportunity it was.

“And why shouldn’t they?” she whispered as she worked. Of all her children, she had come to love them best. They were the easiest to satisfy.

She hawked and spat onto the moonstone, and images of the dark, dirt-lined cave swirled through its milky surface. In it, she saw Herne’s fire-lit face as he bent over her mountainous belly, and for a moment, she was Mother once again, back in the birth chamber, red skin flushed and wet with sweat, body wracked with birth pangs. They’d both known this infant would be their last in this particular incarnation of reality.

The memory of herself splayed like a spider, arms back, thighs thrown wide flashed through her, even as she saw its image reflected in the globe. Her belly contracted once more in a painful heave, doubling her over, causing her to nearly drop the moonstone. She clutched it close, closed her eyes, and saw against her eyelids her final impression of Herne as he caught the caul-covered infant as it slithered out, slick with blood. Through the translucent whiteness of the membrane, she glimpsed a squirming body covered in matted hair.

One blink, and she’d found herself here in her cavern, skin mottled blue-gray, teeth yellowed and jagged, her stick clenched between contorted fingers.

She set the stick aside and for a while, she was busy. The blood that rolled between her thighs and down her legs dried to a slow drip, then stopped and crusted, falling off in flakes that the thirsty stones absorbed. She filled the cauldron, sorted through the contents of the feathered bags made from the carcasses of the Marrighugh’s ravens, summoned up the fire sleeping at the bottom of the fire pit. Finally she turned to her globes that formed the supports on which her cauldron rested.

Besides the cauldron, which was as much a part of her as her own belly, they were her dearest possessions. She cherished and prized them above all else. Originally there had been four, one for each of the primal Elements that made up the Worlds. They had come to her, one by one, when the World was new, and she and Herne were young. With them, she and Herne had created all that was and would ever be.

Now there were only three, the fourth, her favorite, having shattered with such force that it generated a whole new race of beings, each of whom held a piece of the globe. She thought about collecting the pieces of the globe some day, and putting them back together, restoring the fourth globe to its proper place. But that would represent a bigger change than she felt prepared to deal with, and so, while the idea appealed to her, she ignored it for the moment. Some day, though. It amused her to think about it.

She dragged each of the remaining three to the lip of the phosphorescent sea, dipped them into the salty water, then rubbed them clean. When she was finished, she regarded them critically, trying to decide which of the three remaining she liked the best: the black obsidian smoldering with the memory of the fire that had forged it; the lustrous white pearl gleaming pink in the fire pit’s glow, or the moonstone, greenish in the reflection of the phosphorescent sea. She lifted the moonstone, regarding the shifting clouds within its depths. Its surface was as changeable as the Air for which it stood, and she thought this one could be her favorite for a while.

She set the moonstone in its place. It formed a triangular support for her cauldron over the pit along with the globes of moonstone and pearl. With the obsidian and the pearl, it formed a triangular support for the cauldron over the pit. With a great heave and a strength that completely belied her appearance, she set the cauldron in its position. She poked her crooked staff below the black kettle’s rounded bottom, into the center of the fire, and the flames leaped up. She stuck her stick into the brew and gave it an experimental stir. At once she frowned at the image that came swirling out of the depths. She bent her head to take a closer look, just as the gelatinous sea began to boil.

In the cauldron, the image swirled away as swiftly as it had risen. The Hag lifted her head, squinting across the rocky shore into the green glow that rose off the phosphorescent water, then licked her lips as the tips of Herne’s horns broke the surface at last. Water gushed off his broad forehead, cascaded through his black curls like a curtain as his enormous head and shoulders pushed up and out of the sea, revealing the chest and upper arms of a man atop the body of a bull. He strode slowly up the sloping lip, onto the jagged surface of the shore, the razor-sharp edges of the rocks smoothing themselves under his hooves as he approached. His wet tail flicked from side to side, his eyes gleamed red.

His arms were empty.

The Hag withdrew her stick and scurried to the other side of her cauldron. “Where’s the changeling? Where’ve you got it? My cauldron’s hungry and wants its head.”

Herne folded his arms and wouldn’t meet her eyes.

The Hag hissed. “What is it, Father? Where’s the changeling? The cauldron’s cold and must be fed.”

“It’ll have to wait a bit.”

She tried to catch his eye, but again, he wouldn’t look at her. Something dark and ugly uncoiled in her gut, and the Hag took another step closer. “What have you done now, Father?”

“You didn’t see him,” Herne whispered. “You didn’t see him as he was born.”

The end of her stick flared red and in disbelief, she watched tears trickle down his face. “Him? That thing is not a him—it’s not a child meant to live—it’s a changeling for the pot.”

“That pot’s all you ever care about,” Herne thundered. The ground shook, a rock tumbled down and splashed into the sea. In the depths, leviathan shapes shuddered and spun.

The Hag curled both hands tightly around her staff and stood her ground. “That’s what I’m supposed to care about—I’m the one who keeps it all turning. You knew what had to be done even before it was born—we both did. Now go and get it, and bring it here. You know what must be done.”

“It can wait.”

An emotion so foreign the Hag didn’t initially recognize it traced a cold finger down her spine, and she peered up at Herne. The only moment she could compare it to was the moment the pink crystal globe had shattered. It was a moment that was irretrievably different from the moment before it, one that separated time into now and then, before and after. “Wait?” she rasped. Pain lanced through her chest and a sea began to boil deep inside her lungs. “What did you do to the changeling?”

“The sidhe-king took him.”

“What?” A fit of coughing overtook her, and she felt a gush of rheumy mucous rise up from somewhere deep inside. She hawked and spat. The gob was flecked with streaks of blood. Now the fire’s nice and hot, now’s the time to stir the pot. The words danced through her mind and she stared up at Herne, wondering if he realized that the fire now burning in her lungs was his fault. “You let it happen, didn’t you—you gave it to the sidhe-king, didn’t you? Why? Why would you do such a foolish, careless thing? It’s not a child—it’s a changeling. It’s not meant to grow up—it’s meant to go in my stew.”

“He was so beautiful, Mother,” whispered Herne. “You were gone, the moment I pulled him from you. You didn’t see…You couldn’t see…how different he was…from all the others…all the other changelings…” His voice trailed off, he closed his eyes and shook his head. Then he looked down at his open hands, gazing with something like wonder on his face. “I never saw such a perfect child—his arms and legs so round, so pink. He was like a rose dipped in milk, and his eyes were green, then gray and his head was covered in curls soft as spider silk and black as—” He broke off and turned away, his hands clenching into fists.

“Black as the shit you’ve landed us in,” the Hag screeched. “Blacker than any midnight you’ve yet to see—have you forgotten Lyonesse?”

“He’ll come down to your cauldron sooner or later—everything does.” Herne reared back, narrowed eyes flaring red. His chest appeared to broaden and deepen, his head widened so that more than ever he resembled an enormous bull towering over the tiny woman.

The Hag didn’t flinch. Another burst of coughing overtook her and this time the phlegm landed next to Herne’s foremost hoof. “And how long do you expect me to wait, Father? What will feed my cauldron? What will keep it turning, while this beautiful changeling of yours slithers through the land?”

“I’ll bring him myself if he causes trouble.”

“He’s already caused trouble—I saw it in my cauldron. I didn’t understand what I was seeing, but I do now. All Faerie’s in uproar—Father, what do you think you’ve started?”

“I was going to say his hair was black as yours was, Mother.” Herne dropped his shoulders and turned away, head bent. “Perhaps I should’ve brought him here, let you see. You’d understand.”

“Of course you should’ve brought it here. It doesn’t belong in the World. It belongs in the cauldron. That’s the way it goes—take the changeling, toss it in, stir it hard, watch it spin.”

“I couldn’t let you do that.”

“Bring it here at once.”

Herne shook his head. “I can’t do that.”

“You have to do that.”

“It’s already too late—they gave him a name.”

A name. The first anchor of awareness into one’s own flesh for every being—no matter what sort of being it was—began with a name. A changeling never had a name. It wasn’t supposed to live long enough to need one. The disruption she’d glimpsed in the cauldron was a greater rift than she’d realized. “You have to fix this, Father.”

“Why can’t you just agree to wait a bit? You know he’ll end up here eventually like everything else.”

The weight of all existence fell upon her like an enormous rock, and for a moment she wondered if she would ever breathe again. Automatically, because it was the only thing she knew to do, the Hag tottered to the cauldron. She dipped her stick into the brew, and the cauldron rolled gently, settling into place onto the three globes. Tentatively, feeling as if the ground beneath her feet might open and swallow them all, she began to stir in a widening figure eight as she frowned into the broth. “This isn’t something easily undone, Father. This one’s got away from us—gotten itself a name, even. Oh, this is a clever one, indeed. Cauldron only knows what havoc this one will wreak.”

The weight was like a black cloak, settling over her as dense as the soupy water lapping against the rocks. It choked her throat, made the words hard to form and turned her voice into a guttural growl. “Round about the circle goes, dark to light and back it flows, now the fire starts to burn, and the brew begins to churn. Gently simmer in the pot, while the changeling-child rots—take it, break it, let it burn, that Hag to Maiden then return.” But even as she chanted, even as she bent her back and pulled the stick through the frantically bubbling brew, she knew it was already too late.

1

THEN

White Birch Druid Grove, Garda Vale

The trixies were restless and the butter wouldn’t churn. Meeve’s messenger, one of her elite corps of warriors called the Fiachna, and sorely afflicted with arrogance, had come and gone and Catrione had been glad to see him go. Since dawn, rain had been sluicing off the thatched roofs like water from an overturned bucket, and while at one time, the thought of his wet, uncomfortable journey might’ve quietly pleased her, this was the first quarter Catrione had ever served as Ard-Cailleach, the head sister of the Grove, and she was too caught up in the turmoil spiraling all around her to give him another thought.

She dodged the widest puddles as she hurried across the chilly yard toward the low stone still-house, but her feet were soon soaking wet, her hems sodden. The oldest cailleachs, on whom she might’ve relied for support and advice, had all left for the MidSummer rites at Ardagh, summoned there early to a special conclave by the ArchDruid, Connla. Catrione, being one of the younger sisters and head of the Grove for the quarter was left with the few druids either too old to travel or too young to be called. There were reports of blight spreading across the land, of increasing numbers of unnatural births—two-mouthed fish and six-legged calves—and rumors that goblins were stirring. The queen’s messenger didn’t say why Meeve wanted her daughter, Deirdre, home. He had not once looked directly at Catrione, nor any of the other druids, and after he left, the serving maid who’d warmed his bed spoke of trouble between the ArchDruid, Connla, and the Queen.

But nothing seemed to account for the fact that knots wouldn’t stay tied, fires wouldn’t stay lit, water wouldn’t boil and bread was slow to rise. Not to mention the trixies, who spilled and spat and quarreled and caused so much aggravation that that very afternoon, she’d banished them to their dens below the Tor shortly after discovering that an entire batch of starter had to be scrapped, leaving the entire Grove with no means of making bread unless the still-wives had more.

Catrione paused under the eave as a huge black raven shrieked at her, then rose and flapped off. Startled, she put her hand on the still-house latch as the old rhyme ran through her mind: One for sorrow. The door swung open, seemingly of its own accord. Catrione gasped as three anxious faces materialized out of the stillroom’s gloom the moment she put her foot across the threshold, and she wondered if they’d been watching for her.

“Catrione, you have to let us take the child.” Bride, the chief still-wife, broad-breasted as a turtledove but sharp-eyed as a hawk, closed one hand on Catrione’s wrist and pulled her inside. “Deirdre’s child—it’s gone too long past its time.”

“Sisters,” Catrione managed, feeling weak in the knees. Deirdre the High Queen’s daughter, once Catrione’s best friend among the sisters, had doubly disgraced herself and the Grove. Not only had she lain with a brother outside the sacred rituals, but a few months after he’d been banished, she’d admitted to carrying his child.

Druids lay with each other only as part of sacred ritual, and then only after preparation and precautions against the conception of a child, for such couplings produced dangerous rogues and other anomalies. This pregnancy had gone long beyond anything normal, and now, having resisted the sisters’ arguments that the child should be aborted, Deirdre was approaching three months, at least, past term. The child was still alive and squirming, and Deirdre refused to do anything more to hasten her labor than to drink the mildest of tonics.

Catrione felt as if her legs might give way beneath her, but Bride’s clasp seemed to communicate a subtle strength, allowing her to sink onto a long wooden bench.

“You know we must,” Bride was repeating. “You must allow it.”

Baeve, tall and thin as a wraith, spoke from over Bride’s shoulder, as Sora, youngest of the three, shut the door. “You know we’re right, Catrione. It’s not natural.”

Catrione knotted her fingers together over her stained linen apron. “But, sisters—”

“Think of Deirdre,” said Sora, all soft voice and hands that fluttered around Catrione’s shoulders like shy birds.

“Think of the Queen,” said Baeve as Catrione met her eyes.

“It’s not good for her,” Bride was saying. “And look what’s happening here. This is the kind of thing that’s happening all over Brynhyvar.”

Baeve’s expression made Catrione pause. The messenger had gone away, but his parting words were that both Meeve and her sister Connla, the ArchDruid of all Brynhyvar, would be stopping on their way to Ardagh. But even as one side of Catrione wondered why the ArchDruid wasn’t at Ardagh already, she recognized that for all their reasons, the women were right. And yet to order the child taken felt like betrayal.

The memory of Tiermuid’s words, his voice like sand-washed silk, whispered through her. Protect her.

And so Catrione had, not because Deirdre was her dearest friend, the one among all the twenty or so sisters who really did feel like a sister, but because he’d asked it of her, Tiermuid, whose black hair fell around his shoulders, lustrous as a woman’s, his eyes so faint a blue they were nearly sidhe-green. She and Deirdre were not the only sisters who giggled and blushed when Tiermuid was around, and if Deirdre had been the one to fall completely under his spell, the fire he’d lighted in Catrione smoldered secretly still, tamped down only by long force of hard discipline. To order the child—his child—taken felt like an arrow in her heart.

“We know how much you love Deirdre. We know how hard this has been for you.” Bride’s face puckered like a dumpling. She pushed wayward wisps of gray hair under her coif and covered Catrione’s hands with her own, eyes steady and unwavering. “But we’ve no choice.”

“What will we tell the ArchDruid when she comes, otherwise?”

“What will we tell the Queen? Her knight said she’d stop here herself on her way to Ardagh, didn’t he?”

Catrione raised her eyes to the bunches of drying herbs hung along the rafters, the baskets of nuts and berries and seeds. Somewhere amidst all that profusion was the potent combination that would drive the child out at last. A tingle ran up her spine and down her arms. She could’ve left at Beltane, for her father Fengus, the chieftain-king of Allovale and nearly as powerful in his own right as the High Queen, had been left without a druid in his own house when the last one died. But Deirdre was here, and the child was due, and she’d stayed.

But that wasn’t the only reason, Catrione knew, if she was honest with herself as she was required to be at every Dark Moon ritual. Tiermuid might return. The term of his banishment from the Land of a year and a day was nearly completed. She closed her eyes and wished any of the older sisters present, even Eithne, whose tongue was as cutting as her eye was quick to find the least fault. She had maintained all along that the child should be aborted, while Catrione had been careful never to voice an opinion. No wonder they made me Ard-Cailleach, she reflected bitterly. It’s a kind of test.

“Please,” said Baeve.

Catrione rose, back straight, deliberately shutting at all thoughts of Tiermuid’s naked body, slim and white in the moonlight bending over Deirdre’s darker flesh. That way lies madness—look at what’s happened to Deirdre.

“We know you don’t want to,” Sora said, eyes liquid and large as a doe’s, skin nearly as pale and satiny as a sidhe’s.

“But we hope you see you must.” Bride sat back, folding her arms.

“We have to end this unnatural thing,” Baeve put in.

Catrione held up her hands as she heaved a deep sigh. She was druid, she had always been druid, and this desperate striving urgency building in her belly was a result of the Beltane to Solstice ritual abstention from any kind of coupling. The fire kindled at Beltane must be allowed to burn. That’s why she was feeling this growing need, every time she thought of Tiermuid. Druids did not love each other. Not the way you love Tiermuid. The wicked little whisper made her belly burn. MidSummer was coming, when the bonfires on the Tors would call out the sidhe, and the druids would couple their fill, infusing the land. But until then, the energy had to be suppressed. “Sisters, you’ve convinced me. What do you want me to do?”

“Go get her,” answered Baeve.

“Bring her here,” added Bride.

“What if she won’t come? What shall I do then?”

“If she won’t come, call the men,” said Baeve.

“What men?” Catrione blinked.

“The men who’ll be waiting outside the door as soon as we call for them,” replied Baeve.

Catrione stiffened. So this had been previously planned out. “Did Niona put you up to this?” Niona MaFee, just a few years older than Catrione, and the daughter of a poor shepherd somewhere far to the north, had been jealous of Catrione, the daughter of the chief of Allovale, from the moment Catrione had arrived at the White Birch Grove nearly fourteen years ago. Since Beltane, when Niona had not been among those chosen to accompany the older cailleachs to Ardagh, she’d grown even more resentful.

The women exchanged glances, and Bride said, “Everyone—even the neighboring chiefs—are talking. Why, just yesterday young Niall of the glen was here, telling us his sheep were sickening and to see if we had a remedy, and Niona happened to be here. Then she went with him while he spoke to Athair Emnoch about his trees—you were with the Queen’s messenger.”

Catrione’s cheeks grew warm. No one had even mentioned the young chief’s visit. Her jaw tightened. She balled her hands into fists, determined to keep control, and said, “You want me to do this now?”

“There’s a bit of time,” said Baeve with a glance at the other two. “We’ve got to get a few things ready—”

“And you look like you could use a rest,” said Sora.

“Why not lie down for a turn of a short glass,” said Bride. “I’ll send Sora with a cup of something with strength in it when all’s ready.”

Catrione nodded at each in turn, wondering if this was how her father felt before setting out on a cattle raid. She trudged across the courtyard, listening to the fading sounds of the flurry of activity that began the moment the door-latch clicked shut behind her. Her sandals slapped against the slates, the smell of roasting chicken wafting through the air made her nauseous. The rain had eased but the sky was as leaden as her mood. The low white-washed buildings with their beehives of thatch looked like giant children squatting under rough woven cloaks. The courtyard was deserted and she was glad. She picked up her skirts and ran as another downpour suddenly intensified. Once inside the long dormitory, she stopped before Deirdre’s door, fist raised.

She let out a long breath, considering whether to knock or not, whether to try to reason with her friend once again. But she’d had that conversation too many times, and the dull, dead feeling in her gut told her exactly how it would end—Deirdre would refuse, the men would have to be summoned and she, Catrione, would have to go down to the still-house, tired and unprepared. Don’t do that to yourself, she thought. Take the time you need to do it right.

Preparation was everything. If there was anything she’d learned in the last fourteen years it was never attempt anything—healing, ritual or oracle—without properly preparing oneself, one’s tools and one’s environment. But, oh, Great Goddess, why can’t this child just be born? The hollow echo of her footsteps was the only answer.

The long corridor stretched before her, the end shrouded in gloom, every closed door on either side a silent reproach. Most of the rooms were unoccupied. The sisterhouse had been built many years ago, and gradually, fewer and fewer sisters and brothers came to stay. All the Groves were far smaller than they used to be, and some had closed completely. Now that so many had gone to Ardagh, there were only a dozen left.

The deeper into the shadows she went, the more the walls around the doors seemed to shimmer and blur. A tingle went down her spine. It was not unheard of that the OtherWorld occasionally intersected with a corridor—any place that wasn’t one place or another, or was a conduit between two places, was a possible portal. She felt a shimmer in the air around her and out of the corner of her eye, she thought she saw a narrow pale face and heard the tinkle of a high-pitched laugh. It would do her good, she thought, to seek out the embrace of a sidhe, fleeting as it might be. It would relax her, help her think. Later, she promised herself. Later I’ll slip up on the Tor and find my way to TirNa’lugh. But not now.

The sense of overlap faded as another shiver, stronger, went down her back. She paused before her own door, hand just over the latch. It stood slightly ajar, and Catrione knew she was always careful to shut it firmly. She looked up and down, but there was no one about.

She pushed it open. Her dog, Bog, was stretched out beside the cold hearth, apparently asleep, and Catrione gasped to see Deirdre, mountainous belly spilling over the armrests, sitting in the chair. Deirdre turned to look at her, beady eyes unnaturally bright in her puffy face. Her cheeks were flushed, but in the gloom, her skin appeared mottled gray and white. A white coif covered her hair. “What’re you doing here?” Catrione faltered with a hand on the door.

“We know what they want you to do, Catrione.” Her voice was a low rasp.

“It’s not what they want me to do.” Catrione collected herself as quickly as she could. Deirdre’s unblinking stare unnerved her, and she was puzzled that Bog didn’t stir. “Deirdre, this can’t continue—the child will grow so large, it won’t be able to be born. Don’t you see—we’re all worried about you.”

“Why do you want to hurt us?” The final sound was an almost reptilian hiss.

Catrione knelt beside the chair and picked up Deirdre’s hand, swallowing revulsion. Deirdre’s fingers looked like five fat sausages, her slitted eyes like a pig’s. But Catrione forced herself to look into Deirdre’s eyes and say, as gently as she could, “No one wants to hurt you. We want to take care of you. We’re worried about you, Deirdre. Strange things have been happening lately—”

“My baby is not a strange thing!” Deirdre cried. She pulled her hand away, cradling her vast stomach with both arms. She shut her eyes and tilted her face so that her cheek nearly touched the rounded tops of her enormous breasts, as she murmured in a low horrible croon, “Leave us alone…leave us alone…Why can’t you all just leave us alone?”

Revulsion turned into resolve. The others were right. How could I have been so blind? she thought desperately, even as she said, “I have left you alone, Deirdre, and I see I was wrong. Please, don’t argue with me—the midwives won’t give you anything that hasn’t been given to hundreds—”

“What they want us to take will kill us—” Again, Deirdre’s voice trailed away into a soft hiss as her coif fell off, revealing lank strands of sweat-soaked hair and wide patches of blotchy scalp.

Only druid discipline kept Catrione from recoiling openly. “When did your hair start falling out?”

But Deirdre was on her feet and moving faster than Catrione could’ve imagined possible. “Leave us alone. Don’t bother sending for the men—” There was something in the way she said it that told Catrione she knew what the still-wives had planned. “We won’t go with them.”

“How did you know—?” whispered Catrione. Deirdre’s continued use of the word we was ghoulish for some reason.

“It’s amazing how delicate an expectant mother’s senses can be,” Deirdre snapped. She got to her feet, head lowered, ponderous and slow as a boulder slowly gathering momentum. “We know it was you, Catrione. Even he never guessed. But we know. And we know something else, too, something you don’t think anyone else does. We know who you want. We know who you need.” She leaned closer and the wet stench of her body enveloped Catrione in a sickening miasma that made her gag. “You’re so blind, Catrione. You don’t see, and because you can’t, you think no one else can, either. Well, you’re wrong.”

The silent, sudden words struck Catrione like stones pelting her chest. Her jaw dropped, and before Catrione could gather her wits, Deirdre was gone and out the door. She knows…she knows. The words pulsed through her brain. That can’t be possible. No one ever knew. Even when she taunted me…I never admitted anything.

Catrione put one hand on the nearest chair to steady herself, and Bog caught her eye. Forgetting Deirdre, she knelt beside him, one hand on his head. He didn’t stir at her touch, didn’t open his eyes, didn’t thump his great white plume of a tail, and in a moment of awful realization, she knew he was dead. He’d seemed fine all that day, she thought as disbelief descended on her. She tried to remember the last time she’d looked into his deep brown eyes, fondled his silky ears, tried to think what she’d been doing the last time she’d seen him. Her mind was a complete blank, filled with a raven’s screech. One for sorrow, was all she could think.

Deirdre. Find her. The unequivocal command yanked Catrione into the present, galvanizing her. With one last look at Bog’s poor limp body, she shut her door, and paused, looking both ways down the empty corridor. Find her.Catrione picked up her skirts and ran down the shadowy corridor toward the rain-shrouded dusk.

Hardhaven Landing, Far Nearing

Wind-driven rain slashed against the panes of yellowed horn, and the shutters rattled against the latch as the storm howled around the tower room. In the hearth, a log cracked and split in a shower of sparks, stinging Cwynn’s bare legs like a hundred bees, chasing him out of yet another dream of the woman with the honey-blonde hair. Her now-familiar features dispersed into a swirl of color as he came to himself with a start, just in time to wonder briefly who she could possibly be. The girls who caught his eye were usually dark-haired, like Ariene the midwife’s daughter, the mother of his sons. He knocked his head against the stone hearth and opened his eyes to see his grandfather, Cermmus, watching beady-eyed from his pillow. “Sorry,” he muttered.

“Hard day?”

“Thought it would never end.” Cwynn cleared his throat and shook himself awake. The storm had risen fast out of flat water and hazy sun, catching him off guard and farther away from the shore than a one-handed fisherman should be when the weather was bad. Until his feet had actually touched land, Cwynn’d believed it more likely than not he’d find himself feasting in the Summerlands. The sound of off-key singing, followed by loud laughter and catcalls filtered up from the hall, and he remembered there were three strangers in the keep tonight who wore odd-patterned plaids and supple leather doublets with high boots polished to a fine sheen. He’d had no chance to speak to them himself, for Cermmus had left word with every occupant of the house, apparently, that Cwynn was to come to him directly. A whoop from the floor below sounded like Shane, Cwynn’s uncle, who, at thirty-five, was only five years older than Cwynn. “I lost the whole day’s catch, and the nets—the mast—the boat’s going to need a lot of repairs.” He held up his hook. “I put a hole in the side.” He braced himself.

But to Cwynn’s disbelief, Cermmus only shifted under the sheet. “Forget the catch, never mind the boat. There’s—”

Cwynn stared. “Never mind?” Was his grandfather not aware there were two more mouths to feed this summer? Duir and Duirmuid, his twin boys, were weaned and hungry. And there were no men in the midwife’s house to provide for them. “We needed that catch, Gran-da—the fish aren’t running this year like they should. Why, Ruarch was saying—”

“Did you get a look at those strangers down there?”

“I saw them. I figured if there was something about them I needed to know, you’d tell me.”

“I was waiting for you to ask.”

“No sense wasting your breath, eh?”

The old man nodded, and what lately passed for a smile flickered across his face. Then his expression grew serious and he rose up on one elbow, fumbling beneath his pillow. “Come here, boy. I have something for you.” He began to cough, a hard, hacking cough that brought Cwynn to his side, his right hand extended to help him sit up, a clay cup of water awkwardly held in the curved iron hook that had served as his left ever since the accident.

“Drink this, Gran-da,” he said.

The old man waved him away. “Don’t fret about me, boy.” Cermmus cleared his throat, hawked and spit expertly into a metal pot on the other side of the bed. “Here.” He held out what looked like a piece of folded yellowed linen. “Take it. It’s yours. I should’ve given it to you before, but after Shane killed your father—”

It was much heavier than Cwynn expected. He unfolded the stiff, yellowed fabric, frowning as he unwrapped the round gold disk. It was about the size of his palm and nearly as thick. A border of intricate knotwork was etched around the edge. He turned it over. It was warm from his grandfather’s bed. The delicate spiral reminded him of a seashell, studded here and there with tiny crystals, spinning out from an enormous emerald in the center. “What is this thing?”

“The druids make them. We all had them—I sold mine off for food in the years the fish ran slow. Could have another made if I had the gold for it, which I don’t. But I didn’t think it wise to bring that one out.” Cermmus turned his head and spat into a clay ewer. “Pull that stool closer, boy. I don’t want to shout.”

“Are you saying this is mine?” Cwynn asked as he obeyed. The acrid scent of a sick man’s body blended with wet wool and damp dog and the heavy scent of fish that clung to everything beneath his grandfather’s thatched roof.

Cermmus coughed again, and this time he accepted the cup. “I couldn’t let your uncle know it was here—especially after…after, well, you know. I was afraid he’d steal it, sell it.” His mouth twisted down, and Cwynn knew he was remembering the terrible day ten years ago when his father, Ruadan, had accused Shane, his younger brother and Cwynn’s uncle, of lying with his Beltane-wife.

“And what if I did?” Shane had laughed. He was twenty-five then; dark-haired and tanned, strong and agile from a life spent outdoors on the water, much-liked by all the women, whereas Ruadan, more than twelve years Shane’s senior, was balding and beginning to wear his age.

Ruadan had lunged across the table, clearly intent on wrapping his hands around his younger brother’s throat. Quicker than Cwynn could blink, Shane was on his feet and his knife was buried to its hilt in Ruadan’s chest. Cwynn leaped at his uncle, and it had taken six men to pull him off. The druid court at Gar called it self-defense. Shane paid a blood-fine to Cwynn, which really amounted to no more than assigning him a portion of what he expected to inherit from Cermmus, which wasn’t much to begin with, and the matter was considered settled.

But Cwynn never trusted his uncle again, and Cermmus had never been quite the same since. The old man shook his hand, dragging Cwynn back to the present. “It’s yours. You keep it, now. You keep it safe. Don’t lose it.”

“So what’s this all mean?” He turned the disk over awkwardly, squinting at its markings in the candlelight. The druid script was impossible for anyone without their training to decipher, but he could see that the tiny gems scattered across it clearly had some meaning.

“It’s why those men are here,” Cermmus said. “It’s your birthright, it’s your heritage.”

“I don’t understand.” Cwynn squinted at the intricate workmanship.

“That’s your mother’s line, there. The ancestors from your mother.”

At that, Cwynn looked up. This disk clearly indicated the line of a clan rich and well-renowned. “So who’s my mother? Great Meeve herself?”

“Aye.”

Cwynn guffawed. “All right, Gran-da, why don’t you tell me the real story?”

The old man shrugged as a muffled burst of laughter rose from the hall. “That is the real story. The other you were told—well, I guess we told you that to save your father’s honor. It were something of a blow, you see—but you believe what you like. You find a druid to tell you what that says, and maybe you’ll believe that.”

“Meeve the High Queen is really my mother?” Cwynn turned the amulet this way and that, as if changing the direction could somehow snap its meaning into focus. He felt as if the floor beneath his feet had suddenly started to dip and roll like the deck this afternoon.

“She wasn’t the High Queen when she bore you—she was years from that, a thin slip of a girl, she was, with a head like flame. Her mother Margraed who was as fine a piece of flesh in her day as Meeve, was High Queen and she demanded such a high son-price it would’ve beggared us. Now Meeve was a pretty girl, and all that, but not worth every thing I had. So I told Margraed we’d take you instead, and that was one time her strategy backfired. You should’ve seen her face when I looked at her and said ‘no.’ See, she thought she was going to get her hands on Far Nearing that way—establish a foothold, so to speak. Fooled her good, we did. And when we told you your mother was a Beltane-bride, it wasn’t a lie, for that’s how it happened you were made.”

Just like my boys, Cwynn thought. “Why didn’t anyone ever tell me?” Cwynn asked. But he thought he could guess the answer. His grandfather was proud like all the people clinging to a precarious existence on the windswept neck.

“Didn’t much like Meeve,” the old man said. “Didn’t much like her mother.”

“Those men brought this?” Cwynn peered at the gems. They were set at seemingly random intervals and he realized, in a flash of insight, that they represented places where the line diverged or crossed with another. The disk seemed to whisper to him, teasing him. Even the gold and the gems only seemed to imply that the information they encoded was even more valuable. He had to tear his attention away from it to listen to his grandfather.

“Oh, no, lad, that came with you. Shane was a child himself. He never knew about it, and I never had a reason to take it out before this. Meeve’s invited you to a family reunion of sorts, at MidSummer. In Ardagh.”

“I can’t be going off to Ardagh—MidSummer’s less than a fortnight away. The fish are just starting the summer run at last—”

The old man exploded into another coughing fit. A late spring cold had settled in his chest, and nothing the old women did eased it. The fact that he refused to allow Cwynn to ride to the mainland and find a druid didn’t help, either. “No, no, there’s more to it. Seems she’s got a girl in mind for you to wed.”

“What?” Cwynn leaned forward, then peered over his shoulder, as if expecting someone to materialize on the spot. “How—Who—What if I were already wed?”

“Well, boy, that’s why the men are here, so they say.” The old man hawked and spit again. “Throw another log on, boy. I can’t seem to get warm tonight. But Meeve wouldn’t much care, I can tell you that. She won’t see young Ariene as any impediment, believe—”

“I don’t know Ariene would see herself an impediment,” Cwynn said softly. The accident that had taken his hand had also taken both her brother and his rival for her affections, and Cwynn was always bothered by the feeling that Ariene believed he’d dispatched Sorley as coldly as Shane had his own brother.

“That’s for you to say. You should consider the one Meeve has in mind for you, though. I’m sure you could do a lot worse.” He cleared his throat, gesturing for the cup again. When he’d had another long drink, he said, “And it’s an interesting knot right there. She’s suggesting a match ’twixt you and the daughter of Fengus, chief of Allovale.”

Cwynn shrugged. The name meant nothing. “So?”

“If there’s anyone Meeve despises, it’s Fengus, mostly because he’s been hankering after the High King’s seat for as long as Meeve’s been on it. Ever since she made it clear she wouldn’t marry him, he’s been trying to drum up rebellion—even tried to drag me into it. Told him I wanted no part of it.”

“You don’t like Fengus much, either?”

“He’s one of those kind who doesn’t like no for an answer. He just keeps coming back, hoping to badger the answer he wants out of you. Never much cared for badgers.”

“No, you prefer fish, don’t you, grandfather?” A blast of wind and another deluge of rain shook the window frame and Cwynn reached over the bedstead and checked the latch as Cermmus pulled his shawl tighter around his shoulders. “So what do you think I should do? Go with them?”

“No, you’re meant to stay here until Meeve’s escort comes. She’s sending your sister and your brother after you. But you can’t wait. You have to get out of here.”

“Why?”

“Cat’s out of the bag. Shane knows who you are.”

“He didn’t, before?”

Cermmus could only shake his head. Cwynn reached for the basin, held it beneath his grandfather’s chin. “’Course not,” he answered when he could. “If I didn’t tell you, did you think I’d tell him? I don’t want you here, boy. It’s good Meeve’s acknowledged you. But it’s better you get out of here. Shane might get it in his head you’re worth more dead than alive.”

“What do you mean?” Cwynn frowned.

Cermmus met his eyes. “Something happens to you, now that it’s out you’re Great Meeve’s son—what do you suppose your head-price’s worth now?”

“What are you talking about?”

The old man leaned over and smacked his head. “Would you get the fog out of that skull and think, boy? Shane arranges to have you murdered—he kills you himself—some day, out on the ocean, say, when there’s no one else around to say it wasn’t a freak wave come out of nowhere and take you away with it, or mermaid swim out of the water and pull you down with her. You have two sons—Meeve’s grandsons—and you’re valuable here, aren’t you? With no proof of murder—or even any suspicion of one, who do you think will benefit from any head-price Meeve’s bound to pay?”

“You really think Shane would do something like that?”

“I know my son. I think Shane is very capable of arranging to have you killed, if he thinks there’s something in it for him. Even without a hand, you’re yet a queen’s son, and you do bring in quite a bit of fish, even so. He’d have no trouble finding three adults to swear to your worth.” Their eyes met and the memory of that terrible night rose up unspoken between them.

“So where do you expect me to go?”

Cermmus leaned forward, his voice a rough whisper. “Get yourself to Ardagh. Leave the house tonight—go sleep in the village, at Argael’s house if you will. As long as you have that disk, none’ll question who you are. And besides, you favor her about the chin.” The old man fell back against his pillow, and Cwynn noticed a grayish pallor around his mouth that even the firelight didn’t seem to redden. “She can make you a chief in your own right, give you land and cattle—you’ll never need to fish again.”

“I like to fish.”

“Ocean’s already taken your hand. How many chances will you give her to take the rest?” The old man rolled on his side. “The life Meeve can set you up in is a better one than this.”

“But—but what about this?” Cwynn raised his hook.

“What about it?”

“I thought one couldn’t be king—”

“Can’t be High King if you’re maimed, but you can be chief of finer fields than these.”

“But what about my boys? Ariene and her mother? Her aunt?” It was the death of the brother whose loss affected the family most keenly, for he’d been the one to keep his mother and sister and aunt all fed. It was a role Cwynn tried to take on, and though Argael, the mother, appreciated his efforts, it had little effect on Ariene.

Cermmus clutched his arm with surprising strength. “You do what I say, boy—Shane’s already gotten away with one murder. You think I’d let my own great-grandsons starve? You have to live long enough to reach Meeve. You do this for them, too, you know.” Cermmus gestured to the flagon beside the fire. “Pour me more.”

The cup shifted in his hook, and the liquid sloshed as Cwynn struggled to do as asked, a heavy feeling settling in his chest. “I don’t like leaving you, Gran-da. What if Shane—”

“I’m not worth as much dead as you are. I’ve already disinherited him.” Cermmus met Cwynn’s eyes. “You have to understand something, boy. This changes everything for you. This isn’t just about marrying some girl. Meeve’s about to hand you a big piece of something, because that’s how she does things. She’s constantly playing one off against another, and you, my boy, stand to benefit. It’s your destiny, after all—you better get yourself in a state to accept it and all it will entail.”

Cwynn handed Cermmus the full cup and when the old man had taken a long drink, he said, “What if I don’t want it? What if I don’t want any part of this destiny of mine, whatever it’s to be?”

“Then you’re a madman and I don’t want any part of you.” The old man hawked and spat. “What’re you crazy, boy? Spent too long in your boat? This is your chance to solve the problem of Shane for you forever. If Meeve’s planning on displaying you to Fengus, she’ll have to make sure you’ve a household of your own, and that includes warriors, real warriors, not these pirate-thugs. What’s wrong with you, boy? You mazed?”

Cwynn refilled the cup, set it on the rickety table beside the old man’s bed and met his eyes. “I guess I am, a bit. It’s not every day you’re told something like this, after all. Are you sure that’s what you want me to do?”

“You want to stay and wait for Shane to find a chance to kill you, that’s up to you. You want to go and claim what’s yours, I’ll tell them you’ve gone fishing.” With a long sigh, Cermmus settled back against his pillows. His face was wet with sweat in the gloom, but he pulled the blankets higher. “Just can’t seem to get warm tonight,” he muttered.

Cwynn tucked the amulet into the pouch he wore over his shoulder at his waist then rose to his feet. As he was about to lift the latch, Cermmus spoke again. “Take my plaid with you, boy. It doesn’t smell as much like fish as yours.”

He wants me to make a good impression. Cwynn’s throat thickened, and he had a hard time saying, “What will you tell Shane, if he asks where it is?”

“I’ll tell him you took it fishing.” Cwynn considered whether or not to hug the old man, but Cermmus cleared his throat again, then turned on his side, his back decisively to Cwynn. “Go on now, will you? By the time you dither, twill be dawn.” He punched the pillow. “Hope I can sleep.”

He wants to pretend this is just another night. Cwynn unhooked the plaid from its nail. He shut the door, folded the plaid carefully, and looked at the closed door. “I’ll make you proud, Gran-da,” he whispered softly.

“Proud doing what?”

Cwynn nearly hit his head on the low-beamed ceiling. Shane was leaning on the wall at the top of the steps, arms crossed over his chest, wearing the self-satisfied smirk he always wore when he was drunk. “Fishing was off today. Told me where I might look tomorrow.”

“Old man’s relentless, isn’t he? What makes him think you’ll be able to put a sail up, let alone fish?”

“Storm’s already passing,” Cwynn answered, feeling trapped.

Shane nodded, listened. The howling wind had quieted, and even the rain had eased. “So it has. Best get to bed then, nephew. First light comes early.” He stood aside to let Cwynn pass. Their eyes happened to meet. Shane’s lips curved up but the expression in his eyes didn’t change. The old man’s right, Cwynn thought with sudden certainty. Shane would kill him at the first opportunity. But if he left, would his boys be safe? Uneasiness raised the hackles at the back of his neck as he pulled the cloak around himself and slipped out of the keep.

Eaven Raida, Dalraida

From the watchtower of Eaven Raida, Morla bit her lip and squinted into the storm clouds scudding across the sky. Fly away south or west or east, anywhere but here. Just let the sun shine tomorrow—we’re dying for warmth, for light, she prayed. The damp wind whined as if in answer. She pulled her plaid closer around her thin shoulders, and the sound of the fabric flapping around her bony hips drowned out the dull growling of her stomach. It didn’t seem to matter that nearly ten months of famine had passed. Her belly still expected food come sundown. She swallowed reflexively, gazing to the south, willing a rider to come through the rocky pass with the news she longed to hear: Meeve, her mother, the great High Queen, had heard her pleas and was sending corn, pigs, men and druids.

But no matter how hard she prayed, how hard she worked, how many men she sent, no one and nothing came. What was happening, she wondered—why no answer of any kind? No help had come but for the regular payment of her dowry at Samhain and Imbolc. Nothing had come at Beltane. Now the Imbolc supplies were nearly gone, and they’d been forced to eat almost all the seed. If relief of some kind didn’t come soon, they’d be forced to eat the last precious grains. The months before the first harvest were always the hungriest time of any year, with last year’s stores depleted, the new still in the fields. But a cold damp summer last year had brought blight. Blighted harvest meant certain famine.

At least her son, seven-year-old Fionn, was safe at his fosterage on the Outermost Islands, in the same hall where she herself had been raised. Something had warned her to send him away last summer, a few months early. It was but a few days after he’d left that they’d seen the first signs of blight. It was not the first time Morla was glad her son was far away.

“My lady?”

The old steward, Colm, startled her. When Fionn, her husband, had died in the plague year, he had transferred his loyalties seamlessly. But she was surprised the old steward had made it to the top of the tower. Hunger hit the old ones hard, made them weak and susceptible and the damp weather kept them all huddled lethargically around the smoky fire.

“I don’t understand why we’ve not heard more from my mother,” she said, eyes combing the darkening hills, more from habit than out of any real expectation. “I just don’t understand—do you suppose our messengers never got through? Did we not send first word back before Samhain?” She was talking to herself, she realized and the old man was letting her ramble. She turned around to see him leaning against the doorframe, his cloak falling off his shoulders so that his beaked nose and stooped back made him resemble a big bird with broken wings.

“She’s always been prompt with your dowry, my lady.” He cleared his throat. “Don’t fret so.” He took a few steps toward her. “We’ll get through this—we always have. Our people are tough, you’ll see. They’re not used to looking for help from the southlanders.”

That’s not exactly true, she wanted to retort. A flock of crows wheeled around the blighted fields. At least they aren’t vultures. She’d seen those terrible harbingers of death far too often this past spring. Fear gnawed at her more steadily than a fox through a henhouse, with far more stealth, plaguing her with the vague sense that something terrible had descended on the land. She herself had no druid ability at all, but her twin, Deirdre, had been recognized druid practically in the cradle and every so often, Morla felt a twinge or two of what the cailleachs called a “true knowing.” A feeling that she was being suffocated had lately invaded her dreams, and more than anything, Morla wished her mother would send, if nothing else, a druid—a druid to couple with the land, to heal and reinvigorate it. But the last druid house had been deserted nearly two years ago and no others had ever come back. “Mochmorna lies more east than south.” She looked steadfastly at the road snaking through the hills and felt him come to stand beside her.

He turned his back deliberately to the battlement and looked at her. “My lady—” He broke off, and she saw his eyes were dark with care and hollow with hunger. He wore the expression that told her he had something to say he didn’t think she wanted to hear.

“Say what you will, Colm.” Lately, she’d seen a lot of that look.

“What if there’s no help anywhere, and we’re all that’s left?”

Morla stared out over the gray land. Gray land, gray sky, gray stone, gray skin. She didn’t want to think about that. Hardly anyone came this far north in winter, and the spring traffic had been slow, too.

“Dalraida’s on the edge of things, my lady.” He came forward slowly, shoulders hunched against the wind and the few cold drops of rain that stung his cheek. “Things come to us but slowly, they trickle through the passes and filter up from the south. I don’t mean to frighten you, or give you any more trouble. It’s just that—”

“You want me to understand what we might be facing.” Morla met his troubled gaze with a thin, brave smile. Since her husband’s death, she had come to love Dalraida and its people, for it was much like the windswept, rocky shores below her foster mother’s halls, and they were similar in nature to the hardy souls who clustered there. It had taken her longer to learn to love the sheep, but this winter she mourned as the cold winnowed all but the hardiest of the herds, and she keened with all the other women as the spring lambs sickened.

A flicker of movement on the far horizon caught her eye and she squinted harder. Was that a rider?

“—shadows of war, my lady.”

Morla jerked her head around. “What’re you talking about, Colm? No one’s at war—we’re all too weak to fight, and what’s there left to fight over?”

The old man clutched his cloak higher under his chin and shrugged. “The old wives say they see the shadows in the fire, in the water.” He glanced up. “Even we can see the clouds.”

Morla ignored him. It was very hard to see. The road disappeared through a copse of blighted trees and the twilight had nearly fallen. She leaned a little farther over the wall, and just as she was about to give up and return below, she saw a dark dot burst out from beneath the withered branches. The wind whipped the standard he carried, and she was able to glimpse the colors. She pointed into the storm, relief surging through every vein. Thank you, Great Mother, Morla thought as she blinked back tears and wondered for a moment who she meant—the goddess or her own mother. Not for nothing was her mother called Great Meeve. “Look there, Colm. See, coming down the hill—do you see the rider? He’s bearing my mother’s colors.”

The old man tottered forward, shoulders bent against the wind, but before he could speak, to Morla’s horror, she saw a gang of beggars emerge out of the brush. They bore down on the rider, makeshift weapons raised. “Oh, no,” she gasped. With a speed she hadn’t known she still possessed, she raced down the steps, voice raised in alarm.

On the road, Pentand

Watch the road ahead. The rumbled warnings of both Donal, chief of Pentwyr, and Eamus, the graybeard-druid, echoed through Lochlan’s mind, as impossible to ignore as the thickening scent of threatening rain. Ever since he left the house of Bran’s foster parents, the sky had grown increasingly sullen, and now the misty day was falling down to dusk behind the heavy-leaden clouds. Druid weather—a day not one thing nor yet another, neither foul nor fair, a day easy to get lost in fog or stumble into a nest of outlaws—or any petty chieftain with a grudge and a mind for ransom. Lochlan glanced at the boy on the roan gelding beside him. He was fourteen or maybe fifteen by now, Meeve’s youngest child, and he rode with the giddy impatience of a colt run wild.

Bran seemed to know this was something more than an ordinary visit. It was a year earlier than most left their fostering, and the boy appeared to think the druid, Athair Eamus, was responsible in some way. Bran made no secret he was impatient to know what his mother’s summons meant. But Lochlan didn’t think it his place to tell the boy his mother was dying.

The road disappeared into the looming shadows beneath an arching canopy of trees and the skin at the back of Lochlan’s neck began to crawl. He was the First Knight of Meeve’s Fiachna, and so far as he knew, the only person in all of Brynhyvar the Queen had trusted with that information. When Meeve announced she was gathering all her children together, he had volunteered to escort the young prince. Lochlan wanted to gauge for himself the temper of the land she was about to leave, and Bran’s fosterage was closer to the center of the country, south towards Ardagh. What he’d learned troubled him even more than Meeve’s impending death.

Watch the road ahead. The old chief, Donal, had gripped Lochlan’s upper arm with a strength that had surprised the younger knight. “You show Meeve what I gave you. Those Lacquileans I hear she’s so fond of aren’t to be trusted.” The day before Lochlan’s arrival, a shepherd had come down unexpectedly from the summer pastures, bringing troubling news. A cache of weapons had been discovered in a mountain cave, weapons that bore no resemblance to anything made, as far as Donal or Lochlan knew, in all of Brynhyvar. The shepherd brought a sword, a fletch of arrows and a bow, and it seemed everyone in the keep, from scullery maid to blacksmith, from stable hand to bard, had a thought as to who had hidden them.

But old Donal had no doubts. “It’s neither sidhe nor trixies—it’s those foreigners who’ve been paying Meeve such court. They’re carving out toe-holds in the wild places, hunkering down and planning to attack us before winter. You mark my words, there’ll be slaughter while we sleep.” He’d insisted Lochlan take the sword back to show Meeve. Now it was rolled in coarse canvas, tied on the back of Lochlan’s saddle. Watch the road ahead. An enormous raven alighted on a branch just ahead, cocked a beady eye and stared at both of them, piercing Lochlan’s reverie.

“Why’d Mam send for me, Lochlan?” Bran interrupted his thoughts with the same question for the tenth or twelfth time since setting out. “You think it’s because Athair Eamus sent word to Aunt Connla? Did Mam say she knows I’m druid? Is that why they want to see me?”

“There’re could be any number of reasons, Prince,” Lochlan answered, also for the tenth or twelfth time. He watched the bird take flight as they rode beneath its bough, then slid a sideways glance at the boy. He wondered if Meeve even intended to tell him the truth. Calculating as she was flamboyant, Meeve might well decide not to, unless and until the boy himself guessed. “Maybe your mother missed you.”

Fortunately Bran accepted that answer and subsided into silence. He reached into his leather pack, withdrew a withered apple and bit into it. “Want one?” he asked, munching hard. Lochlan shook his head, but the boy held out the bag. “I have a bunch in here—Apple Aeffie gave ’em to me.”

“Who’s Apple Aeffie?” asked Lochlan. Bran appeared ordinary enough—his nut-brown hair curled at the back of his neck and spilled over the none-too-clean collar of a soon-to-be-outgrown tunic, the edges of his sleeves ragged, his leather boots scuffed and crusted with mud. He had no look of a druid about him at all.

“Apple Aeffie’s what we call Athair Eamus’s cornwife. He used to jump the room with her each Lughnasa. She died last Imbole, but she comes to me in dreams. She tells me stories of who I was before. Do you ever wonder who you were, before?”

“Before what?”

“Before now.” Bran chomped on the chewy fruit.

“Before I was what I am? I was a lad much like you, of course. I wasn’t a chief’s son, but my family’s—”

“No, no.” Bran swallowed the entire apple, core and all. “I meant before you went to the Summerlands. In your last life—don’t you ever wonder?” He licked his fingers, looking at Lochlan expectantly.

Keep a close eye on the boy. He’s more than he seems. And watch the road ahead. Those were the druid’s parting words, spoken when they were already in the saddle. “No, boy, I can’t say as I ever have.” Lochlan wished there’d been more time to ask the old druid what he meant, but the boy’s next words startled him.

“Do you suppose Athair-Da is dying? I know he misses Apple Aeffie.”

“Dying?” Lochlan looked more closely at the young prince. The old druid had seemed in fine enough health to him. Athair Eamus wasn’t a young man, by any means, but he certainly didn’t appear as if the Hag was ready to send him to the Summerlands, either. “What makes you think he’s dying?”

The boy shrugged, gazed moodily into the distance. “I don’t know—the thought just came to me. You think maybe Mam’s planning on sending me to Deirdre’s Grove-house? Deirdre’s been there a long time. She used to send me things. I’d like to go there. Think Mam means to give me leave to start my training early?”

A flicker of movement out of the corner of Lochlan’s eye made him glance in the opposite direction, and when he turned back, he saw that Bran was staring in the same direction.

“Did you see that trixie, too?” he asked.

“What trixie?”

“The one that went darting across that branch and down that trunk—I know you saw it, too—you turned to look at it.”

“It was a squirrel, boy.”

“No, it wasn’t,” Bran insisted. “It was a trixie.”

Only druids could see the earth elementals, and only druids could control them. Lochlan regarded Bran more closely. Deirdre, one of Bran’s older twin sisters, had been born druid, though not much good it had done her. Her disgrace was one reason Meeve wanted nothing to do with druids, Lochlan knew, even though the great queen would not admit it. But Bran himself, as far as Lochlan could tell, lacked all signs of any druid ability. He hair was neither pure white nor shot through with tell-tale silver, his eyes were neither bright blue nor impenetrable brown-black, nor lacked all pigment. He was not, so far as Lochlan had heard, particularly gifted in music-making, nor singing, nor recitation, which were all considered certain signs of druid ability and critical druid skills.

Even his seat on the horse, his hands on the reins, didn’t mark him as anything but an adequate horseman. Except for the fact he was Meeve’s son, he seemed as ordinary as an old boot. It would certainly be better for the boy if he were, Lochlan thought, listening with only half his attention as Bran chattered on. The druids as a group did not number among Meeve’s favorites right now, despite the fact that Meeve’s own sister was ArchDruid, or Ard-Cailleach, of all Brynhyvar. As far as Lochlan could discern, Meeve at times appeared deliberately determined to antagonize them.

He’s more than he seems. The old druid’s warning repeated unbidden in his mind. There was something odd about Bran, something difficult to define perhaps, but definitely there. Lochlan tried to remember what Deirdre was like, but he’d not seen her much when she was young.

“Will Deirdre be there? And what about Morla?”

Lochlan stiffened and raised one brow. Druids read thoughts, but only after long training and never without permission. Was it possible this boy could read thoughts without the training? Maybe it was only logical the boy would inquire about his sisters. After all, as far as Lochlan knew, Bran hadn’t seen either of his twin sisters since he was a very young child. And neither had Lochlan, for Deirdre stayed at her druid-house, except for a holiday or two at Ardagh, and Morla, the other twin—Morla was long married. Her husband died a year back, a voice reminded him, and he tried unsuccessfully to push all thoughts of Morla out of his mind. He remembered she came home from her fostering a young woman of sixteen, moody and quiet, dark and ripe as the brambleberries that grew along the beach she loved to wander. He might have married her himself if Meeve hadn’t tapped his shoulder the Beltane after Morla came home. Fleetingly he remembered the stricken look on the girl’s face as her mother had led him out of the hot, smoky hall. She’d been about to pick me. The pang of regret that accompanied that realization was unexpectedly deep. “I don’t know,” was all he said. “They may have work of their own—after all, Morla’s married—”

“She’s not married anymore,” Bran said. “Her husband’s gone to the Summerlands.”

Startled, Lochlan looked at him harder. “How did you know that?” Dalraida comprised the remote northwestern tip of Brynhyvar. Lochlan found it hard to believe that Morla spent much time sending messages back and forth to Bran. In ten years, she’d never come back once to Meeve’s court.

“He came to me last Samhain.”

“Fionn? Her husband?”

Bran stared off down the road, as if he could see the shade rising before him. “Said I’d be seeing her soon and asked me to give her a message from him. It was an answer to her question.”

“What was the question?”

“Oh, I don’t know that. But you see, I’ve been sort of expecting to see Morla since MidWinter.”

Lochlan looked more closely at the boy in the greenish shadows. Meeve had first mentioned bringing Bran home nearly nine full moons ago, just after Samhain. Before he could stop himself, he said, “So what was the answer?”

“No.”

“No what?”

“‘No’ is all the answer he gave me,” said Bran. “He told me to tell her that the answer to her question is ‘no’ and then he vanished.”

There was a queer light burning in the boy’s eyes, reminding Lochlan of the druid fires flickering around the standing stones up on the Tors while they worked their magic within the stone circles. It was not uncommon for the dead to come uninvoked to the living at Samhain, when the veil to the Summerlands was thinnest. But not common, either, and how could Bran know that Meeve had first mentioned bringing both Bran and Morla home shortly after Samhain, right before MidWinter? The road ahead looked very dark. A chill went down his arms. The druids said the trees were aware, and looking down the road, he could believe it. The trees stood on either side, so evenly spaced, it was hard to imagine how random chance gave rise to such order.

Lochlan glanced at Bran’s eager face. It was hard to imagine such an ordinary boy could possess any kind of extraordinary talent at all. He’s not what he appears. Lochlan shifted in his saddle and flapped the reins. Maybe it wasn’t his place to tell the boy his mother was dying, but maybe he should tell the boy the druids weren’t high on his mother’s list of favored people right now, and that he doubted that any plans she had for Bran included druid training. He cleared his throat. “That’s quite an amazing thing, all right.”

The boy narrowed his eyes, his expression an exact replica of Meeve’s when crossed. “You sound like you don’t believe me.”

“It’s not that I believe or don’t believe you, boy. It’s not for me to say.” Thank the Great Mother, he added silently. “But as for the druids—well, there’s something I think you should know. Your mother’s been at odds with her sister, your aunt, for months now, and she’s not at all happy with her. Nor any druids.”

“Because of the blight?”

Lochlan shrugged. Blight was not yet a problem in Eaven Morna. “Blight, goblins, silver—whatever it is, boy, you don’t want to be in the middle of it. So, when you meet her, wait to see what she says to you, before you go telling her you feel you’re a druid. All right?”

Bran frowned, opened his mouth, then shut it.

“Just remember, she’s not just your mother. She’s the Queen of all Brynhyvar, the beloved of the land. You listen, and speak when she asks you, not before.”

Bran made a face, but said nothing.

Night was falling quickly behind the lowering clouds, far faster than Lochlan had anticipated. He wanted all his wits about him, and the road was getting dark. His shoulders ached from a bad night’s sleep. “I say we stop at the next house we come to.”

“All right,” replied Bran. “That suits me—I’m starved.” He caught the reins up in one hand and kicked his heels hard into the horse’s flanks. “Let’s go,” he cried. “I’ll race you!” He took off down the road as the old druid’s warning echoed once more through Lochlan’s mind.

Watch the road ahead. “Hold up, boy,” cried Lochlan as he touched his own heels to his horse’s sides. Keep a close eye on him. With an inward groan, he galloped after Bran who charged heedlessly down the darkening road like a stone tumbling down a mountain. “Wait!” he shouted and plunged headlong into the dark green twilight.

The air was oppressive and very wet and the road appeared to curve up the hill, away from the lake. He heard loud trickling and looked up. A run-off brook wound its way down the mountain and across the road. He’d have to cross the water to continue after Bran, who’d rounded the curve, and now was nowhere to be seen. But instinct—or maybe the old druid’s words—made Lochlan hesitate. You’ve faced Humbrian pirates, the wild men of the Marraghmourns and the outlaws of Gar and now you’re afraid to cross a stream? The doubt that taunted every warrior whispered through his mind. It wasn’t even a stream, really, just a channel that rainwater carved into the hillside. But it was at just such a place that one was most likely to fall into the OtherWorld of TirNa’lugh, where both sidhe and goblins roamed, dangerous to mortals in very different ways, but equal in peril.

He’s more than he appears. “Bran?” he called. “Bran, wait for me.” Cursing Bran beneath his breath, Lochlan spurred his horse forward, and the animal didn’t even seem to notice the water crossing the road. Inexplicably, the light began to fade, the shadows deepened. The road took another turn, pitched sharply up a hill. “Bran?” he bellowed at the top of his lungs. “You wait for me!”

The high-pitched yelp that came in answer galvanized Lochlan. He sped around the turn and pulled up straight.

Bran stood spellbound in the center of the road, staring straight ahead at a naked girl bathing on a riverbank that shouldn’t have been there. A young moon had already risen in the purple sky, spilling silvery light across the sidhe-girl’s shoulders, reflecting off her copper-colored hair with a pale gold glow. Almost black in the shadows, her waist-length hair fell fine as spider silk across her naked breasts and her nipples were pink as quartz and pebbled from the chill of the gurgling brook. She turned this way and that beneath the bending willows, splashing the water all over herself. Droplets gleamed like opals on her shimmering naked flanks, fell like diamonds from her fingertips. A high laugh floated through the trees and Lochlan looked up to see more eyes, more pointed faces and tiptilted breasts peeking through the trees.

“Look, it’s mortals.” The whisper floated down from somewhere up above, and Lochlan saw the red-haired sidhe turn to Bran, arm extended, smiling as she strode up through the water to the bank. To Lochlan’s horror, Bran smiled back and leaned forward, hand outstretched.

“No,” Lochlan bellowed. If this was what the old druid had meant, he should’ve spelled it out for him, not warned him in a riddle so dense it sounded like nothing more than good advice to any traveler. How could they have blundered into TirNa’lugh? Only a druid could take you there, and more important, only a druid could lead you out. There were stories though, of warriors on the brink between life and death, who’d fallen into the OtherWorld, and stayed held captive there by the sidhe. He dug his heels so hard into his horse’s side the animal reared and screamed his displeasure, so that Lochlan had to struggle to bring him under control. Bran didn’t even appear to notice as his own horse began to dance skittishly beneath him. His eyes remained fastened on the sidhe.

The other sidhe were creeping down the trees now, luminous as fireflies, green eyes glowing in their narrow pointed faces. They were all beautiful, all naked, all with long limbs and flowing hair. He could feel warmth emanating off their skin, even as their unearthly fragrance twined around him like tendrils. He forced himself to concentrate on the feeling of the horse, solid and scratchy and real between his thighs, on the weight of the weapons strapped to his back and his waist, on the feeling of the hair prickling on the back of his neck and not on the aching pressure rising in his groin. “Bran,” he said again, this time with even more urgency. He reached over and cuffed the boy’s head. “We’re not meant to be here, remember? We’re on our way back to Eaven Morna, remember? Throw them your apples and they’ll let us go. I’m taking you back to your mother, Bran. Remember? Your mother, Meeve. Your mother wants you home. We’re going home, Bran—home to Eaven Morna. Home to your mother and Eaven Morna.”

“Mother,” Bran repeated, his cheeks pale, his eyes wide, beads of sweat rolling down his face. The sidhe were singing now, something soft and low and nearly indistinguishable from the gurgling brook and the whispering of the leaves, but Lochlan could feel it; tempting and wooing and sweet, twining in his hair, trailing down his back like the long slender fingers that even now were reaching down and out of the branches. If they touch me, I shall be lost, he thought. But he had to save the boy.

“Give them the apples, Bran, now. Now!” Lochlan cried. He swatted Bran across the shoulder. He helped Bran toss the bag to the sidhe and shook the boy’s shoulder. “Home—home to Eaven Morna!”

Drops of sweat big as pearls glimmered on Bran’s upper lip as he stared, mesmerized by the naked sidhe. Lochlan felt his own resolve weaken. He leaned over, wrapped the reins around Bran’s wrists, slapped the horse on the rump. The gelding leaped forward. They fled down the road and across the border, back into a wind and rainswept dusk where, impossibly, the watchtowers of Eaven Morna twinkled on the horizon.

2

Faerie

“Auberon?” Melisande’s soft voice broke the stillness of the summer twilight, taking the King of the sidhe entirely by surprise, penetrating the soft pink fog of dream-weed smoke. His queen seldom attempted the winding climb to his bower at the top of the highest ash of the Forest House because she, unlike almost every other sidhe, was terrified of heights. It was one reason he’d chosen her among all the others to be his Queen. Now she perched in the archway of the bower, quivering only slightly. Her long fair hair, fine as swan’s down, feathered around her shoulders, down her back and chest. In the orange glow of the setting sun, it gave the illusion she was covered in white feathers.