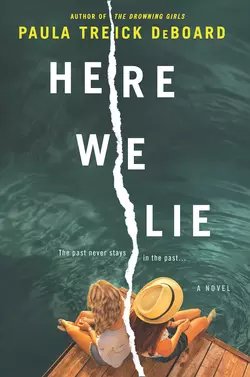

Here We Lie

Paula DeBoard

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 458.46 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: The past never stays in the past… Megan is a girl from a modest Midwest background.Lauren is the daughter of a senator from an esteemed New England family.When they become roommates at an exclusive private college, this unlikely pair forge a strong friendship and come to share their most intimate secrets.As a last hurrah before graduation, Megan joins Lauren’s family on their private island off the coast of Maine for the summer. Late one night, something unspeakable happens. Something strong enough to tear them apart.Many years later, Megan decides to reveal the truth about that night. But the truth can have devastating consequences.Readers love DeBoard:“An unforgettable story…5 stars”“I loved this book”“absolutely entrancing novel”“This is an important book and a great examination of why things play out the way they do in society”“Great summer read!”