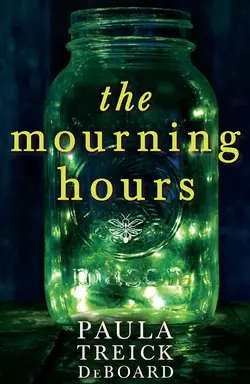

The Mourning Hours

Paula DeBoard

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Триллеры

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 542.29 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: A family’s loyalty is put to the ultimate test…Kirsten Hammarstrom hasn’t been home to her tiny corner of rural Wisconsin in years – not since the mysterious disappearance of a local teenage girl rocked the town and shattered her family. Kirsten was just nine years old when Stacy Lemke went missing, and the last person to see her alive was her boyfriend, Johnny – the high school wrestling star and Kirsten’s older brother. No one knows what to believe – not even those closest to Johnny – but the event unhinges the quiet farming community and pins Kirsten’s family beneath the crushing weight of suspicion.Now, years later, a new tragedy forces Kirsten and her siblings to return home, where they must confront the devastating event that shifted the trajectory of their lives.Tautly written and beautifully evocative, The Mourning Hours is a gripping portrayal of a family straining against extraordinary pressure, and a powerful tale of loyalty, betrayal and forgiveness.