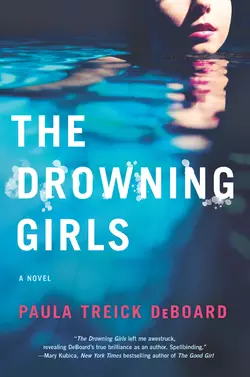

The Drowning Girls

Paula DeBoard

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современные любовные романы

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 152.29 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: Critically acclaimed author of The Mourning Hours and The Fragile World, Paula Treick DeBoard returns with a tale of dark secrets, shocking lies and a dangerous obsession that will change one neighbourhood forever Liz McGinnis never imagined herself living in a luxurious gated community like The Palms. Ever since she and her family moved in, she′s felt like an outsider amongst the Stepford-like wives and their obnoxiously spoiled children. Still, she′s determined to make it work—if not for herself, then for her husband, Phil, who landed them this lavish home in the first place, and for her daughter, Danielle, who′s about to enter high school.Yet underneath the glossy veneer of The Palms, life is far from idyllic. In a place where reputation is everything, Liz soon discovers that even the friendliest residents can′t be trusted. So when the gorgeous girl next door befriends Danielle, Liz can′t help but find sophisticated Kelsey′s interest in her shy and slightly nerdy daughter a bit suspicious.But while Kelsey quickly becomes a fixture in the McGinnis home, Liz′s relationships with both Danielle and Phil grow strained. Now even her own family seems to be hiding things, and it′s not long before their dream of living the high life quickly spirals out of control…