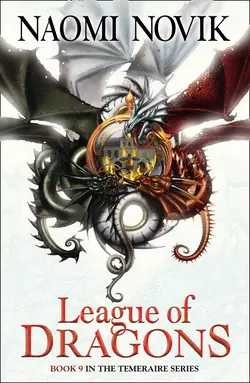

League of Dragons

Naomi Novik

With the acclaimed Temeraire novels, New York Times bestselling author Naomi Novik has created a fantasy series like no other. Now, with LEAGUE OF DRAGONS, Novik brings the imaginative tour-de-force that has captivated millions to an unforgettable finish.Napoleon’s invasion of Russia has been roundly thwarted. But even as Capt. William Laurence and the dragon Temeraire pursue the retreating enemy through an unforgiving winter, Napoleon is raising a new force, and he’ll soon have enough men and dragons to resume the offensive. While the emperor regroups, the allies have an opportunity to strike first and defeat him once and for all – if internal struggles and petty squabbles don’t tear them apart.Aware of his weakened position, Napoleon has promised the dragons of every country – and the ferals, loyal only to themselves – vast new rights and powers if they fight under his banner. It is an offer eagerly embraced from Asia to Africa – and even by England, whose dragons have long rankled at their disrespectful treatment.But Laurence and his faithful dragon soon discover that the wily Napoleon has one more gambit at the ready – one that that may win him the war, and the world.

Copyright (#u2c004f13-30c1-5c1a-8410-7b0e03864e9d)

HarperVoyager

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street,

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain by HarperVoyager 2016

Copyright © Naomi Novik 2016

Map copyright © Robert Bull 2016

Naomi Novik asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

This novel is entirely a work of fiction.

The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008121167

Ebook Edition © 2016 ISBN: 9780008121150

Version: 2016-05-06

Dedication (#u2c004f13-30c1-5c1a-8410-7b0e03864e9d)

To Charles

sine qua non

Map (#u2c004f13-30c1-5c1a-8410-7b0e03864e9d)

Contents

Cover (#u091c5cac-50f5-528c-b423-749647622e56)

Title Page (#u000c4874-0193-5722-bac0-2b7476e9a444)

Copyright

Dedication

Map

Part I

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Part II

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Part III

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Part IV

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

About the Author

The Temeraire Series by Naomi Novik

About the Publisher

Part I (#u2c004f13-30c1-5c1a-8410-7b0e03864e9d)

Chapter 1 (#u2c004f13-30c1-5c1a-8410-7b0e03864e9d)

THE CHEVALIER WAS NOT dead when they found her, but the scavengers had already begun to pick at her body. A cloud of raucous crows lifted when Temeraire’s shadow fell over the clearing, and a stoat slunk away into the underbrush, coat white, muzzle red. As he dismounted, Laurence saw its small hard shining eyes peering patiently out from beneath the bramble. The French dragon’s immense sides were sunken in between her ribs so deeply that each hollow looked like the span of a rope bridge. They swelled out and in with every shallow breath, the movement of her lungs made visible. She did not move her head, but her eye opened a very little. It rolled to look on them, and closed again without any sign of comprehension.

A dead man sat in the snow beside her, leaning against her chest and staring blindly forward, in the ragged remnants of what had once been the proud red uniform of the Old Guard. He wore epaulets and the front of his coat was pockmarked with many punctures where medals had once hung, likely sold to whichever Russian peasants would sell him a pig or a chicken for gold and silver. Flotsam from Napoleon’s disintegrating Grande Armée: the dragon had most likely been driven by hunger to go too far afield, searching for food, and having spent her final strength could not then catch up the remaining body of her corps. She had come down a day ago: the churned ground beneath her was frozen into solid peaks, and her captain’s boots were drifted over with the snow which had fallen yesterday morning.

Laurence looked for the sun, descending and only barely shy of the horizon. Every scant hour of daylight now was precious, even every minute. The last corps of Napoleon’s army were racing west, trying to escape, and Napoleon himself with them. If they did not catch him before the Berezina River, they would not catch him; he had reinforcements and supply on the other side—dragon reinforcements, who would spirit him and his troops safely away. And all this devouring war would have no conclusion, no end. Napoleon would return only a little chastened to the welcoming cradle of France and raise up another army, and in two years there would be another campaign—another slaughter.

Another laboring breath pushed out the Chevalier’s sides; breath steamed out of her nostrils, billowing like cannon-smoke in the frigid air. Temeraire said, “Can we do nothing for her?”

“Let us lay a small fire, Mr. Forthing, if you please,” Laurence said.

But the Chevalier would not take even water, when they melted some snow for her to drink. She was too far gone; if indeed she wished any relief with her captain gone and a living death already upon her.

There was only one kindness left to provide. They could not spare powder, but they still had a few iron tent-poles with sharpened ends. Laurence rested one against the base of the dragon’s skull, and Temeraire set his massive claw upon it and thrust it through with a single stroke. The Chevalier died without a sound. Her sides rose and fell twice more while the final stillness crept slowly along her enormous body, spasms of muscle and sinew visible beneath the skin. A few of the ground crew stamped their boots and blew on their hands. The snow heavy upon the pine-trees standing around them made a muffled silence.

“We had better get along,” Grig said, before the final shudders had left the Chevalier’s tail; a faint note of reproach in his high sparrow-voice. “It is another five miles to the meeting-place for to-night.”

He alone of their company was little affected by the scene, but then the Russian dragons had cause enough to be inured to cruelty and hunger, having lived with both all their days. And there was no real justification for ignoring him; they had done what little good there was to be done. “See the men back aboard, Mr. Forthing,” Laurence said, and walked to Temeraire’s lowered head. The breath had frozen in a rim around Temeraire’s nostrils while they flew. Laurence warmed the ice crust with his hands and broke it carefully away from the scales. He asked, “Are you ready to continue onwards?”

Temeraire did not immediately answer. He had lost more flesh than Laurence liked these last two weeks, from bitter cold, hard flying, and too little food. Together these could waste the frame of a heavy-weight dragon with terrifying speed, and the Chevalier made a grim object lesson to that end. Laurence could not but take it to heart.

He once more bitterly regretted Shen Shi, and the rest of their supply-train. Laurence had already known to value the Chinese legions highly, but never so much as when they were gone, and all the concerns of ensuring their supply had fallen into his own hands. The Russian aviators had only the most outdated notions of supply for their beasts, and Temeraire, with all the will in the world, had too much spirit to believe that he could not fly around the world on three chickens and a sack of groats if doing so would put him in striking distance of Napoleon again.

“I am so very sorry Shen Shi and the others had to go back to China,” Temeraire said finally, in an echo of Laurence’s thoughts. “If we were only traveling in company, perhaps …”

He trailed off. Even the most relentless optimism could not have imagined a rescue for the poor Chevalier: three heavy-weights together would have had difficulty in carrying her. “At least we might have given her some hot porridge,” Temeraire said.

“If it is any consolation to you,” Laurence said, “remember she came into this country as a conqueror, and willingly.”

“Oh! What would the dragons of France not do for Napoleon?” Temeraire said. “When you know how much he has given them, and how he has changed their lot: built them pavilions and roads through all Europe, and given them their rights? You cannot blame her, Laurence; you cannot blame any of them.”

“Then at least you may blame him,” Laurence said, “for trading so far on that loyalty to bring her and her fellows into this country in a vain and unjustified attempt at conquest. It was never in your power to prevent her coming, or to rescue her. Only her master might have done so.”

“I do,” Temeraire said. “I do blame him, and Laurence, it would be beyond everything, if he should escape us now.” He heaved a deep breath, and raised his head again. “I am ready to go.”

The men were already aboard; Temeraire lifted Laurence to his place at the base of his neck, and with a spring not as energetic as Laurence would have liked, they were aloft again. Beneath them, the stoat crept out of its hiding-place and went back to its feasting.

The ferocious wind managed to come as a surprise again, even after so short a break in their flying. The last warmth of autumn had lingered late into November, but the Russian winter had come with a true vengeance now, more than justifying all the dire warnings which Laurence had heard before its advent, and to-day the temperature had fallen further still. He was used to biting cold upon the deck of a racing frigate or aloft upon a dragon’s back in winter, but no experience had prepared him to endure this chill. Leather and wool and fur could not keep it out. Frost gathered thickly on his eyelashes and brows before he could even put his flying-goggles back on; when at last he secured them, the ice melted and ran down the insides of the green glass, leaving trails across his sight like rain.

The ground crew traveling in the belly-netting, shielded better from the wind, might huddle together and make a shared warmth; he had given his scant handful of officers permission to sit together in twos and threes. He could permit himself no such comfort. Tharkay had left them two weeks before, on his way to answer an urgent call to Istanbul; there was no-one else whom Laurence might sit with, without awkwardness—Ferris could not be asked without reflection on Forthing, and equally the reverse; and he could not ask them both, when they might at any moment be attacked. They had to be spread wider than that across Temeraire’s back.

He endured the cold as best he could beneath wrappings of oilcloth and a patchwork fur made of rabbit- and weasel-skins, keeping his fingers tucked beneath his arm-pits and his legs folded. Still the chill crept inexorably throughout his limbs, and when his fingers reached a dangerous numbness and ceased to give him pain, he forced himself to stand up in his straps. He carefully unlatched one carabiner, working slowly with thick gloves and numbed hands, and hooked it to a further ring; he then undid the second, and made his way along the harness hand-over-hand to the limits of the first strap before latching back on.

The natural hazards of such an operation, with half-frozen hands and feet and on a dragon’s back made more slippery than usual with patches of ice, were outweighed by the certain evil of staying still for too long in such cold: he had to stir his blood. At least the instinctive fear of the plummeting ground below was in this case his ally, rather than an enemy; his heart jerked and pounded furiously when his feet slipped and he crashed full on his side, clinging to the harness with one hand and one strap, trees rushing by in a dark-green blur below.

Emily Roland detached herself from a nearby knot of huddled officers, and clambering with far more skill came to his side—she had been dragon-back upon her mother’s beast nearly since her birth and was as much at home aloft as on the ground; she expertly caught his loose strap as the carabiner came banging against Temeraire’s side, and latched it to another ring. Laurence nodded his thanks, and managed to regain his footing; but he was flushed and panting when he regained his place at last.

Temeraire himself kept low to the ground, his eyes slitted almost shut against the glare and the breath from his nostrils that came streaming back along his neck: it made clouds filled with needles of ice that stung Laurence’s face. Grig flew behind, making as much use as he could of the air churned up by Temeraire’s wings. Below them rolled the endless snow and the black bare trees frosted with ice, the fields empty and glittering and hard. If they passed so much as a hut, it remained invisible to them. The peasants had taken to covering their houses in snow up to the eaves, to conceal them from the sight of the marauding feral dragons: they ate their potatoes raw, rather than light a fire whose smoke might betray them.

Only the corpses remained unburied, the trail of dead that Napoleon’s army left behind it. But even these did not linger in the open long: a host of feral dragons pursued them, savage as any murder of crows. If a man fell, they, too, did not wait for the body to grow cold.

Laurence might have called it the hand of justice, that Napoleon’s army should now be hunted and devoured by the very ferals he had unleashed upon the Russian populace. But he could not take any solace in the dissolution of the once-proud Grande Armée. The pillage of Moscow trailed grotesquely behind them: silken cloth and gold chains and delicate inlaid furniture discarded along the sides of the road by starving men who now thought only of bare survival. Their misery was too enormous; they were fallen past being enemies and reduced to human animals.

Temeraire reached the rendezvous an hour later, on the edge of nightfall. He inhaled a grateful deep breath of the cooking-steam from the big porridge-pit as he landed, and immediately fell-to upon his portion. As he ate, Ferris approached Laurence: he was holding several short sticks which he had tied together at the top, making a skeleton for a miniature tent. “I have been thinking, sir, if we propped these over his nostrils, we might drape the oilcloth over them, and have his nose in with us after all. Then his breath shan’t freeze in the night; and we can open a chimney-hole at the top to let it out again. Whatever warmth we might lose thereby, I think the heat of his breath will more than make up.”

Laurence hesitated. The responsibility of their arrangements was the duty of the first lieutenant, and ought to be left in his hands; the interference of the captain on such a level could only undermine that officer’s authority. Ferris would have done better to apply to Forthing rather than to Laurence, allowing the other man to take the credit of the idea, but that was a great deal to ask when Forthing stood in the place that should have been his; that had been his, before he had been dismissed from the service.

“Very good, Mr. Ferris,” Laurence said, finally. “Be so good as to explain your suggestion to Mr. Forthing.”

He could not bring himself to refuse anything which might improve Temeraire’s situation, already so distressed. But guilt gnawed him when he saw Forthing’s cheek color as Ferris spoke to him: the two men standing mirror, the one stocky and squared-off in shoulders and jaw, and the other tall and lean, his features not having yet lost all the delicacy of youth; both of them equally ramrod-straight. Forthing bowed a very little, when Ferris had finished, and turning gave stiff orders to the ground crew.

The oilcloth was rearranged, and Laurence lay down to sleep directly beside Temeraire’s jaws, the regular susurration of his breath not unlike the murmur of ocean waves. The warmth was better than anything they had managed lately, but even so it was not enough to drive out the cold; at the edges of the oilcloth it waited knife-like, and slid inside on any slightest breath of wind. Laurence opened his eyes in the middle of the night to see a strange rippling motion in the cloth overhead. He put a hand out and touched Temeraire’s side: the dragon was shivering violently.

There were faint groans outside, grumbling. Laurence lay a moment longer, and then groggily forced himself up and went outside. The fur he had wrapped over his coat was useless as armor against the cold. The Russian aviators were up already, walking among their dragons and striking them with their iron goads, shouting until the beasts stirred and got up, sluggishly. Laurence went to Temeraire’s head and spoke. “My dear, you must get up.”

“I am up,” Temeraire said, without opening an eye. “In a moment I will be up,” but after a little more coaxing he climbed wearily to his feet and joined the line the Russian dragons had formed: they were all walking in a circuit through the camp, heads sagging.

After they had walked for half an hour, the Russians permitted their dragons to lie down again, this time in a general heap directly beside the porridge-pit. A thick crust of ice had formed over the top; the cooks at regular intervals threw in more hot coals, which broke through the crust and sank. Laurence urged Temeraire to huddle in as well; a great many of the small white dragons curled in around him. The oilcloth was slung again; they all returned to the attempt to sleep. But it seemed to him the cold grew still worse. The ground beneath them radiated chill as a stove might have given off heat, so intense that all the warmth which their bodies could produce was not adequate to push it back.

Temeraire sighed behind his closed teeth. Laurence drifted uneasily, rousing now and again to put his hand on Temeraire’s side and be sure he was not again shivering so dangerously. The night crept on. He roused Temeraire with the other dragons for another circuit. “The banners of the Monarch of Hell draw nigh, Captain,” O’Dea said, he and the other ground crewmen stamping along with Laurence alongside Temeraire’s massive plodding feet. His hands were tucked beneath the arm-pits of his coat. “No wonder if we are o’ertaken, and the dawn find us locked in ice eternal; God save us sinners all!” Then the cold stopped even his limber tongue.

They returned to their place; they slept again, or tried to sleep. Laurence stirred some unmeasured time later and thought morning must be coming near, but when he looked outside the night remained impenetrable: the light was only from torches. A Cossack courier had landed, his small beast already crawling into the general heap. The other beasts made grumbling protests at the cold of her body. Her rider was chattering so badly he could not speak, but waved his hands in frantic haste in the faces of the handful of officers who had gathered around him, the movements throwing wild shadows through the torchlight. Laurence forced himself out into the cold and crossed to join them. “Berezina,” the man was saying. “Berezina.”

A young ensign came running with a cup of hot grog. The man gulped, and they closed in around him to give him some little share of their own warmth. His clothing was coated white, and the ends of his fingers where he gripped the cup were blackened here and there: frostbite.

“Berezina zamerzayet,” he managed; one of the officers muttered a curse even as the courier stammered out a little more around another swallow.

“What did he say?” Laurence asked low, of one of them who had French.

“The Berezina has frozen,” the man answered. “Bonaparte is running for it.”

They were aloft before sunrise, and reached the camp of the Russian advance guard as the dawn crept over the frozen hills. The Berezina was a clouded ghostly lane between high-piled snowbanks. To the north of the Russian camp, a handful of French regiments were streaming across the river in good order, men marching two abreast, with narrower lines to either side of camp-followers and soldiers who had fallen out of the ranks, struggling across alone as best they could: women and children with their heads down, hunched against the cold; wounded men leaving bloody marks upon the ice as they limped along. Bodies lay prostrated beside the lines, and here and there a figure huddled and unmoving. Even with escape open before them, some had reached the limits of their strength.

“That cannot be all of his army?” Temeraire said doubtfully: there were not two thousand men. Upon the hills of the eastern bank, a small party of French dragons huddled together around a pair of guns, established to provide cover for the retreat, but there were only four beasts.

“They are spread out along the river to the north,” Laurence answered, reading the dispatch which Gerry had come running to bring him. The division was a clever stratagem: if the Russians came at any one crossing in strength, Napoleon might sacrifice that portion to save the rest; if the Russians divided themselves to attack more than one, Napoleon could use his advantage in dragons to concentrate several of his companies more quickly than the Russians could do the same. Each group remained large enough to fend off the Cossack harrying bands.

Laurence finished reading and turned to the crew. “Gentlemen,” he said, “we have intelligence that Napoleon has declared to his soldiers that he will not go dragon-back while any man in his army remains this side of the Berezina; if he has not lied, he is somewhere along the river even now.”

A low murmur of excitement went around the men. “If we can only get him, let the rest of them get away!” Dyhern said, pounding his fist into his palm. “Laurence, will we not go at once?”

“We must!” Temeraire said urgently, hunger and cold forgotten. “Oh! Why are the Russians only standing about, waiting?”

This criticism was unjust; the Russian sergeants were already bawling the men into their marching-lines, and even as Laurence ordered his officers to make ready for action, orders were sent running around the rest of the dragons: they were to go and survey the French crossings, and bring back word of any company of unusual strength. “Temeraire,” Laurence said, as he loaded his pistols fresh, “pray have Grig pass the word to look for Incan dragons in particular: there were not many with the French, and those few will surely be devoted to Napoleon’s protection. Ma’am, I hope you will be comfortable in camp,” he added, to Mrs. Pemberton, Emily Roland’s chaperone. “Mr. O’Dea will do his best for you, I trust.”

“Aye, ma’am, whate’er can be done,” O’Dea said, reaching to pull on the brim of a cap he no longer had; his head was swathed instead in a makeshift turban of furs and flayed horsehide, flaps dangling over the ears and the back of the neck. “We’ll strike up a tent and do what we can about some porridge, Captain.”

“Pray have not a thought for me,” Mrs. Pemberton said; she herself was engaged in low conversation with Emily and handing her an extra pistol, one of her own, and a clean pocket-handkerchief.

The French dragons on their hill lifted wary heads when they saw the Russian dragons coming, but did not immediately take to the air themselves; the guns beside them were heaved up, waiting if they should descend into range. Laurence looked across at Vosyem, the Russian heavy-weight nearest him; there was little love lost between himself and Captain Rozhkov, but for the moment they were united in their single goal. Rozhkov looked back, his own flying-goggles blue, and they shook their heads at each other in wordless agreement: Bonaparte would not be with this company, the most exposed to Russian attack; in any case, there were no carriages nor wagons, and very few cavalry.

They flew northward along the line of the river: already a dozen marching ant-lines dotted across the frozen white surface. Behind them, the French company fired up signal-flares in varied colors, surely signaling to their fellows ahead. As the Russian dragons closed in on the next crossing, a volley of musketry fired to greet them, and they had to go higher aloft: painful in the cold weather, and there was not an Incan dragon to be seen; only a few French middle-weights gathered by their guns, who eyed the mass of Russian heavy-weights with some anxiety.

There were, however, a dozen wagons crossing the river under guard by the company, pulled by teams of horses, many of them having lost their hoods: they went frantic and heaving with the dragons overhead. And the wagons were laden not only with wounded but with pillaged treasure, and in alarm Laurence heard Vosyem rumble interest, cocking her head sideways to peer down, as one of the wagons toppled over, and a load of silver plate slid out across the snow, blazing with reflected light.

Laurence heard Rozhkov shout at her, and haul brutally upon the spiked bit she wore, to no avail. The other Russian heavy-weights had seen the treasure as well—they were snarling at one another, snapping, throwing their heads violently to shake their officers off the reins. “Whatever are they hissing for?” Temeraire said, craning his head about. “Anyone can see Napoleon is not there. Napoleon is not there!” he repeated to the Russian dragons, in their tongue.

Vosyem paid no attention. With one last heave of shoulders and neck, she flung Rozhkov and his two lieutenants off their feet, leaving them dangling by their carabiner straps, and her reins were loose. With a roar, she banked sharply, her wings folding, and stooped towards the baggage-train. The other Russian heavy-weights roared also and flung themselves after her, all of them, claws outstretched: worried more about which of them would reach the laden carts first than about the enemy.

“Oh! What are they doing!” Temeraire cried; Laurence looked away, sickened. In their savage eagerness, the Russian beasts were making no effort to avoid the hospital-carts or the camp-followers, and wounded men were spilling out across the ice with cries of agony. The Russian dragons skirmished among them, heedless; others were smashing the rest of the carts, dragging them up onto the bank, mantling at each other with hisses and displays of their claws and teeth.

Temeraire turned wide circles in distress aloft, but there was nothing to be done. He could not force a dozen maddened dragons to come to heel, even if the Russian beasts had not already disdained him. “Temeraire,” Laurence called, “see if you can persuade the smaller beasts to come along with us. If we can only find Napoleon, we can return and perhaps by then marshal the other heavy-weights; we can do nothing with them at present.”

Temeraire called to Grig and the other grey light-weights, who were not unwilling to follow him; none of them could hope for a scrap of treasure with so many heavy-weights engaged. Even as they turned away, two of the Russian dragons went smashing into the frozen surface of the river, clawing at each other, rolling over and over, and the ice broke with a crack like gunfire: three wagons and dozens of screaming men and women sank at once into the dark rushing water beneath.

Temeraire’s head was bowed as he flew northward, leaving the hideous scene behind them. They flew past another four crossing-points: Marshal Davout’s regiments, much diminished yet still in fighting-order. He had few guns and almost no dragons left, most of them forced to flee ahead of the retreat outside Smolensk, but his soldiers had climbed up onto the edges of their hospital-wagons, holding their bayonets aloft to form a bristling forest of discouraging points. “A courier has told him, I suppose,” Temeraire said, “how the Russian dragons were behaving: oh! Laurence, I hardly know how to look at them. That they should think I would do such a thing, go after a hospital-cart, and only for a little silver!”

“Well, it was quite a lot of silver,” Grig said, in a faintly envious tone, then hastily added, “which does not of course mean they were right to do it: Captain Rozhkov will be so very angry! All the officers will, and,” he finished glumly, “I expect they will take away our dinners.”

Temeraire flattened his ruff, not liking this speech very much. He beat away quickly, urgently. The river swung back eastward beneath them, snow blowing in little drifts across the ice. Over the next stand of hills, they found one smaller crossing already completed: tracks through the snow on both sides of the bank, and the ground atop the highest point on the eastern bank trampled and bared of snow, where dragons had lifted away the guns and followed the company. But the soldiers had already vanished into the trees on the western bank.

Laurence swept the countryside and the river ahead with his spyglass, anxiously. As little as he wished Napoleon to escape, he feared crossing the enemy’s lines. The Russian light-weights were not accustomed to any combat beyond their own internal skirmishing; they did not make a strong company, and now there were French dragons on every side, backed with guns and companies in good order. “We must begin to think of turning back,” he said.

“Not yet, surely!” Temeraire cried. “Look, is that not a Cossack party, over there? Perhaps they will know where Napoleon has gone.”

He flung himself ahead, eagerly. It was indeed a Cossack raiding party: seven small beasts, courier-weights perhaps half Grig’s size, each of them carrying a dozen men hanging off their bright hand-woven harnesses. The Cossack men were armed with sabers and pistols; their clothing was stained dark in places with dried blood. Parties such as theirs had been harrying the French rear all the way from Kaluga; they had been largely responsible for the speed of Napoleon’s collapse, but they had neither the arms nor the dragon-weight to meet regular troops. The chief man waved them a greeting, and Dyhern shouted back and forth with him in Russian, through Laurence’s borrowed speaking-trumpet; they landed, and Temeraire came to earth beside them. Dyhern leapt down and went to the Cossacks, carrying Laurence’s best map; after a quick conversation, he came back to say, “The Prince de Beauharnais is crossing over the next two miles with nine thousand men and twelve dragons: none of them are Inca.” Laurence nodded silently, grim with disappointment; but then Dyhern moved his finger further north on the map and said, “But there are two Incan beasts with the Guard company crossing here, where the river forks, with a carriage and seven covered wagons.”

“Only two dragons?” Laurence said sharply.

The Cossack captain nodded and held up two fingers, to confirm, and then moved his hand in a circle and flung it in a gesture westward, conveying flight. “He says all the other Inca dragons flew away west four days ago in a great hurry: they took nothing with them,” Dyhern said.

“They must have run out of food,” Temeraire suggested, but Laurence doubted. For the Incan dragons, all the potent instincts of personal loyalty were bound up in their Empress, now Napoleon’s consort. He was the father of her child, which had secured their devotion to him. That in extremis he should have chosen to send away those beasts who could have been relied upon to protect him, first and foremost, seemed unlikely.

“But we have not seen any other French heavy-weights, either,” Temeraire said. “None, except that poor Chevalier—so perhaps he had to send them all away, and kept only those two.” He was hovering, looking yearningly north, his ruff quivering. “Laurence, surely we must try. Only imagine if we should learn that he escaped us, so near—”

Laurence looked again over the map. Only the merest chance, and between them and the fork lay a force of twelve French dragons, and a strong company of men and guns. If the French should see a danger to Napoleon, and turn back in force—“Very well,” Laurence said. He could not bear it, either. “Dyhern, will you ask them to show you a way to come at the fork from the east? We must go around de Beauharnais, far enough to be out of sight, to have any hope of coming at his chief.”

Temeraire flew low, just brushing the snow from the tree-tops, and flat-out; setting such a pace that the small Russian dragons fell behind, just barely keeping in sight. Laurence did not slow him. Speed was the only chance, if there were any. If the Cossacks’ intelligence were good, then Temeraire alone could halt Napoleon’s party, if he arrived in time to catch them out in the open; then the Russian light-weights might catch them up, and provide a decisive blow. But if the Cossacks had been mistaken, if there were more heavy-weight dragons or more guns, a company too great for Temeraire alone to stop, then the Russian light-weights could not make victory possible. There was no chance, either, of going back to get the Russian heavy-weights—and just when their power might have told significantly, if the French truly had sent away all of their own larger beasts.

Laurence was well aware that if they found a force too large for them, he would have a difficult struggle against Temeraire’s inclination to keep him from an attempt which could only end in disaster. When Temeraire turned at last sharply westward again, going back towards the river, Laurence stood in his straps, despite the still-ferocious wind and cold, and trained his glass ahead of their flight. The trees broke; he could see the two branches of the river flowing, the marshy ground around them, and then his heart leapt. A very large covered wagon was trundling up the far bank onto a narrow road, being pulled not by horses but by one of the Incan dragons; and behind it rolled a carriage, large and ornamented in gold, with a capital N blazoned upon the door. Another Incan dragon waited anxiously beside the guns on the eastern bank, its yellow-and-orange plumage so ruffled up the beast looked three times its size—but even so, not up to Temeraire’s weight. There was not another dragon in sight.

“Laurence!” Temeraire said.

“Yes,” Laurence said, his own much-restrained spirits rising; two dragons and guns, and on the order of three hundred men, to guard only a carriage and a wagon-train? He reached for his sword, and loosened it in its sheath. “At them, my dear, as quickly as you can. Mr. Forthing! Pass the word below, ready incendiaries!”

Temeraire was already drawing in air, his sides swelling; beneath his hide trembled the gathering force of the divine wind. Faint cries of alarm carried to Laurence’s ears as the French sighted them; the Incan dragon in the lead abandoned the wagon and leapt aloft, beating quickly, and the second came up to join it, both going into a wide, darting, back-and-forth flying pattern, making themselves difficult to hit. The men on the ground sent up a volley of flares even as Temeraire swept in.

“Ware the guns,” Laurence shouted to Temeraire; a flick of the ruff told him he had been heard. Twelve-pound field guns, two of them, spoke together, coughing canister-shot and filling their approach with shrapnel; but Temeraire had already beaten up out of their range, skimming the top edge of the powder-smoke cloud, and as he swept over the emplacement, the bellmen let go a dozen incendiaries.

“Ha! Well landed!” Dyhern shouted: fully half of the incendiaries were exploding among the French gun-crews. Others rolled away; one burst on the river and sank into the hole it had blown itself in the crust. And then Temeraire was past; he doubled back on the guns and unleashed the divine wind against their rear—the endless impossible noise, ice-coated trees on the bank shattering like glass bottles, the housing of the guns cracking and coming apart. One still-smoking barrel rolled down the hill and carried away two massive snowbanks; it struck the back wheel of the carriage, shattering it, and the cascade half-buried the entire vehicle in snow.

The Incan dragons dived, ready to make raking passes along Temeraire’s vulnerable sides. But Temeraire twisted sinuously away to one side and traded slashing blows with the heavier beast: blue-and-green plumage with a ring of scarlet around its eyes, which gave it a fierce look. There were nearly two dozen Imperial Guardsmen on its back; rifle-fire cracked from their guns, the whine of a bullet passing not distant from Laurence’s ear, and six of them leapt for Temeraire’s back as the dragons closed.

The sky wheeled around them, a tumult of colors and cold wind; then Temeraire pulled away, leaving the Incan beast bleeding. “Make ready for boarders!” Forthing was shouting. The Guardsmen had leapt across to Temeraire’s back latched one to the other; only two of them had made hand-holds, but that had been enough to hold the rest on.

The Guards made intimidating figures: they were all tall, heavily built men, bulky in leather coats and fur caps drawn tightly around the head, with broad sabers and four pistols each slung into their harness-straps. They steadied one another until they had all latched on; then in a tense, disciplined knot they came forward swiftly along the back, covering one another’s advance with pistols held ready.

Laurence now had cause to regret his threadbare crew. He had but few officers; his choices had been scant, in New South Wales, and of that motley selection only a handful had survived the wreck of the Allegiance: small Gerry, who could not yet hold a full sword, brandishing a long knife instead; for midwingmen, besides Emily Roland, he had only Baggy, still gangly in the midst of getting his growth and only lately advanced from the ground crew; and thin, stoop-shouldered Cavendish: brave enough, but likelier by the look of him to be blown overboard by a strong gust of wind than to cross swords with one of Napoleon’s Grognards.

Laurence had not wanted to take men from his fellow-captains; Harcourt had offered, handsomely, when they had parted ways in China. But Laurence knew he and Temeraire were deep in the black books of the Admiralty; he might have been reinstated, as a matter of form and necessity, but no-one could imagine that those gentlemen would turn a kindly eye on any officer coming from his crew. That consideration might now doom the men he did have, or even Temeraire.

By unconscious agreement, Roland and the boys were thrust back to make a final defense between the oncoming boarders and Laurence—a prospect which he could only find grotesque; and yet the fault was his own, for not taking more pains to fill out his crew. Forthing had no second or third lieutenant behind him, no older midwingmen who might have bolstered their resistance; there were no riflemen aboard.

Ferris and Dyhern drew their swords; they joined Forthing, clambering along the line of Temeraire’s back to meet the Frenchmen. Laurence drew his own sword and his pistol—the metal painfully cold to the touch; he could only hope it would fire.

The world turned over again, a dizzying spiral, and then suddenly they were in a steep climb: the Incan dragons were pursuing Temeraire hotly, trying to prevent him getting his breath back again; they were wary of the divine wind. Laurence had learned the trick of leaning hard into his straps, his boots planted firmly against hide, to keep from falling over during hard flying, but even so he could not avoid a disorientation that blurred all the world into meaningless shapes and colors.

He shook his head and blinked streaming eyes. The Guards had all kept their feet. Forthing climbed into range—he stood up in his straps—he fired his pistol; one of the Guards fired his at the same instant. A cloud of smoke, and the Guardsman fell; Forthing jerked, twisting around in his straps. A spray of blood burst from his cheek and was slapped back onto his skin by the wind, bright red around a torn bleeding hole: the bullet had gone into his mouth and through the side of his face. Another pistol fired off, the grey smoke anonymous; Laurence could not tell whether the shot was on their side or the French.

Dyhern was grappling with one of the Guardsmen; he was a big man himself, but the other, a younger man, was bearing him down. Ferris looked down Temeraire’s back, and then, greatly daring, reached down and unlatched his second strap, and let go the harness: he fell ten feet straight down onto the man overpowering Dyhern, and managed to catch onto one of his straps. Before the Frenchman could recover, Ferris had pistoled him in the face. He thrust the spent pistol into his belt, and bent to latch himself on in the dead man’s place; the corpse went falling away.

All sensation of weight abruptly vanished. Temeraire had opened just enough distance from his pursuers to turn; now he arced over, mid-air. He hung suspended a fraction of a moment, and then he was plummeting, down onto the two Incan dragons so close on his heels. The dragons shrieked, bending their heads away to protect their eyes from Temeraire’s claws and teeth, entangled with one another. The world fractured: Temeraire roared in the dragons’ faces as they all fell, the divine wind drumming beneath his skin again; he roared again, and a third time, his wings beating the air wildly. They were falling, all falling together; Laurence clung to the straps, straining, and saw the other men doing the same. Like being in the tops mid-gale, struggling to reef a sail. And then Temeraire smashed the two dragons together down into the riverbank beneath him, tree-limbs snapping, snow and ice erupting all around like gunpowder smoke.

Laurence shielded his eyes with his sleeve, but the flying snow thickly coated the top of his head, covered over his mouth and ears. They had stopped moving. If Temeraire had been wounded in the fall—

He dropped his arm only to see one of the Guardsmen slash his own straps and come leaping in four quick strides directly towards him. Emily Roland lunged at the man from one side, Baggy from the other; but he had more than a foot in height on either of them, and bulled his way past them. He had a saber ready in his hand; Laurence pulled up his own pistol and fired—with no result; the powder was too wet. He flung the pistol into the Frenchman’s face instead, and met the descending sword on his own: a brutal impact. The Frenchman pounded down on Laurence’s sword with main strength, trying to beat it out of his grip, and seized his arm.

The surface shuddered beneath them, Temeraire shaking himself free of the coating of snow. The Frenchman let go his hold on Laurence’s arm and seized his harness instead, to keep his footing. They were close enough to have embraced; Laurence managed to lean back far enough to club the man across the jaw with the guard of his sword-hilt. The man shook his head, dazed, but struck down again with his saber; the Chinese sword shrieked as the two blades scraped against each other, but held.

They were matched and straining; then the bright crack of a pistol, and hot blood and brains spurted into Laurence’s eyes. He jerked aside. Emily Roland had shot the man in the back of the head. Laurence wiped blood and ice from his face as Temeraire reared up onto his feet and shook himself steady. The two Incan dragons lay still and broken beneath him, shattered by the divine wind more than by the fall; the green-blue-plumed head had fallen back limply across the ice, a blaze of incongruous color.

Laurence looked back. The last two Guardsmen on Temeraire’s back had surrendered: Forthing was taking their guns and swords, and Ferris was binding their arms. All their fellows upon the dragons had been slain: the bodies of men lay scattered around the wreckage of the beasts.

Further up the river, the soldiers around the carriage stood frozen and staring back at them, clutching their rifles, pale. Laurence felt Temeraire draw breath, and then he roared out once more over all their heads, shattering, terrible. The men broke. In a panicked mass they fled, some scrambling and slipping up the river in blind terror; some flying back eastward, undoubtedly into the waiting arms of the Cossacks; most however ran for the western bank, vanishing into the trees.

Temeraire stood panting, and then he threw off the battle-fever; he looked around. “Laurence, are you well? Oh! Have you been hurt? What were those men about, there?” he demanded, narrowly, catching sight of the prisoners.

“No, I am perfectly well,” Laurence said; his shoulders would feel that struggle for a week, but his skin had scarcely been broken. “It is not my blood; do not fear.” He laid his hand upon Temeraire’s neck to soothe him; he well knew what the fate of the prisoners would be, if Temeraire imagined them responsible for having harmed him.

For once, however, Temeraire was willing to be diverted. “Then—” Temeraire’s head swung back towards the gilded carriage, standing now alone upon the bank and still buried deeply beneath the snow. He leapt, and was on the riverbank. He pushed the large wagon away, with a grunt of effort, and scraped the bulk of the drift away from the carriage with his foreleg. Laurence sprang down, with Dyhern following; they went to the door, which had been thrust half an inch open against the snow before it stuck, and dragged it open against the remnants of the drift.

Two women inside were huddled in terror half-fainting against the cushions: a beautiful young lady in a gown cut too low for respectability, and her maid; they clung to each other and screamed when the door was opened. “Good God,” Dyhern said.

“The Emperor,” Laurence asked them sharply in French. “Where is he?”

The women stared at him; the lady said, in a trembling voice, “He is with Oudinot—with Oudinot!” and hid her face against the maid’s shoulder. Laurence stepped back, dismayed, and looked back at the wagon: Temeraire reached for the cover with his talons, seized, tore.

The sun blazed on gold: gold plate and paintings in gilt frames; silver ornaments, brass-banded chests and traveling boxes. They threw back the covers: more gold and silver and copper, sheaves of paper money. They had taken only Napoleon’s baggage: the Emperor was safely away.

Chapter 2 (#u2c004f13-30c1-5c1a-8410-7b0e03864e9d)

“IT DOES NOT SEEM reasonable,” Temeraire said disconsolately, “that when I should have liked nothing more than to have a great fortune, none was to be had; and now here it is, just when I should have preferred to catch Napoleon. Not,” he added, hurriedly, so as not to tempt fate, “that I mean to complain, precisely; I do not at all mind the treasure. But Laurence, it is beyond everything that he should have slipped past us: he has quite certainly got away?”

“Yes,” Hammond answered for Laurence, who was yet bent over the letters which Placet had brought them all from Riga. “Our latest intelligence allows no other possibility. He was seen in Paris three days ago, with the Empress: he must have gone by courier-beast the instant his men had finished crossing. They say he has already ordered another conscription.”

Temeraire sighed and put his head down.

The treasure remained largely in its wagon, which was convenient for carrying. Laurence had insisted on returning those pieces which could be easily identified, such as several particularly fine paintings stolen from the Tsar’s palace, but there were not so many of those; nearly all of it had been chests full of misshapen lumps of gold, which had likely been melted in the burning of Moscow, and which no-one could have recognized.

Temeraire did not deny it was a handsome consolation; but it did not make amends for Napoleon’s escape, and while he was not at all sorry that the Russian heavy-weights now looked on him with considerably more respect and had one and all avowed that in future they would listen to him when he told them not to stop, they would not believe that he had not done it for the gold. “I was doing my duty,” he had said, stiffly, “and trying to capture Napoleon, which is what all of you ought to have done, too.”

“Oh, yes,” they all answered, nodding wisely, “your duty: now tell us again, how much gold is in that middling chest with the four bands around it?” It was not what he called satisfying.

“And now Napoleon is perfectly comfortable at home again,” Temeraire said, “having tea with Lien, no doubt; I am sure she has not spent the winter half-frozen: I dare say she has been sleeping in a dozen different pavilions, and eating feasts. And we are still here.”

“Still here?” Hammond cried. “Good Heavens, we took Vilna not three days ago; you cannot consider our residence here of long duration.”

But Temeraire personally did not make much difference between Vilna and Kaluga; yes, he could see perfectly well that upon the map there were five hundred miles between them, and it was just as well to have crossed them, and anyone might say that they were in Lithuania instead of Russia; but he found little altered, and nothing to be very glad of, in their present surroundings. The coverts, on the very fringes of the city, were unimproved; the ground frozen ever as hard as in Russia proper, and though there was more food to be had, it remained unappetizing: dead horses, only ever dead horses. Laurence had arranged for a bed to be made up for him of straw and rags, which daily the ground crew built up a little more, but this was a very meager sort of comfort when Temeraire might look down the hill at the palace in the city’s heart lit up with celebrations from which dragons were entirely excluded, although the victory could not possibly have been won without them.

“Indeed I am almost glad,” Temeraire said, “that the jalan had to return to China; I should not know what to say to them if they had met with such incivility; not to speak of ill-use. It is one thing to endure any number of discomforts in the field, on campaign; one must expect these things, and I am sure no-one would say we were unwilling to share in the general privation. It is quite another to be left sitting in mud, in frozen mud, and offered half-thawed dead horsemeat, while the Tsar is feasting everyone else who has done anything of note, and yet he never thinks of asking any of us.”

“But he has,” Hammond said earnestly. “Indeed, Captain,” he added, turning towards Laurence, “I am here to request your attendance: it is the Tsar’s birthday to-day, and it is of course of all things desirable that you should attend as a representative not only of His Majesty’s Government—” Temeraire flattened his ruff at the mention of that body of so-called gentlemen, but Hammond threw an anxious look at him and hurried on. “—but of our friendship, indeed our intimate ties, with China; I wondered if perhaps you might be prevailed upon to wear the Imperial robes of state, which the Emperor has been so kind as to bestow upon you—”

Despite a strong sense of indignation at being himself neglected in the invitation, Temeraire could not help but approve this idea, wishing to see Laurence, at least, recognized as he deserved. But Laurence had a horror, a very peculiar horror, of putting himself forward. He would at once refuse, Temeraire was sure; he always required the most inordinate persuasion to display himself even in honors which he had properly earned—

“As you wish,” Laurence said, without lifting his head from his letters; his voice sounded distant and a little strange.

Hammond blinked, as though he himself had not expected to meet with so quick a success, and then he hastily rose to his feet. “Splendid!” he said. “I must do something about my own clothes as well; I will call for you in an hour, then, if that will do. I hope you will pardon me until then.”

“Yes,” Laurence said, still remote, and Hammond bowed deeply and took himself out of the clearing nearly at a trot. Temeraire peered down at Laurence in some surprise, and then in dismay said, “Laurence—Laurence, are you quite well? Are you ill?”

“No,” Laurence said. “No, I am well. I beg your pardon. I am afraid I have received some unhappy news from England.” He paused a long moment still bent over the letter, while Temeraire held himself anxious and stiff, waiting: what had happened? Then Laurence said, “My father is dead.”

Lord Allendale had been a stern and distant parent, not an affectionate one, but Laurence was conscious that he had always had the satisfaction of being able to respect his father. While not always agreeing with his judgment, Laurence had never blushed for his father’s honor, both in private and in public life unstained by any reproach; and in this moment, Laurence was bitterly conscious that his father could not have said the same of his youngest son. His treason had broken his father’s health, had certainly hastened this final event.

Laurence did not know if his father could ever have been brought to understand or to approve the choice which he had made. He had reconciled himself to his own crime only with difficulty, and he had before him every day all the proofs which any man could require, of the sentience and soul of dragons. He had seen those dragons dying hideously, worn away by the slow coughing degrees of the plague; he had with his own eyes witnessed their agony and seen the carrion-mounds of a hundred beasts raised outside Dover. He had known what the Ministry did, in deliberately infecting the dragons of Europe with that disease: a wholesale murder of allies and innocents as much as of their enemies.

All this had been required to turn his hand to the act, to make him bring the cure to France and give it into Napoleon’s hand. And even so, he had recoiled from the act at first. He had dreamt of the moment of crisis again only three nights ago; of Temeraire saying, “I will go alone,” and afterwards in the dream Laurence found himself in an empty covert, going from clearing to clearing, calling Temeraire’s name, with no answer.

With an effort, Laurence recalled himself to his circumstances: Temeraire’s head was lowered to peer at him, full of anxiety. “I am well,” he said again, and put his head on the dragon’s muzzle as reassurance. “I am not overset.”

“Will you not take anything? Gerry,” Temeraire called, raising his head, “pray go and fetch a cup of hot grog for Laurence, if you please; as we have nothing better it must do,” he added, turning back down. “Oh, Laurence; I am so very sorry to hear it: I hope your mother is not hurt? Have the French invaded them again? Ought we go at once?”

“No,” Laurence said. “The letter is a month old, my dear; we are too late for the funeral rites.” He did not say that he should scarcely have been welcome, with or without a twenty-ton dragon. “He died in his bed. My mother is not ill, only much grieved.” His voice, low, faded out without his entirely willing it to do so. The letter was in his mother’s hand, brief, sharp-edged with sorrow. His father had been hale and vigorous five years ago, still in his prime; she might justly have hoped not to be made a widow so soon. When Gerry came running with the hot cup, Laurence drank.

“In his bed?” Temeraire was muttering to himself, as if he did not understand; but he did not press any further for explanation; he only curled himself around Laurence, and offered the comfort of his companionship. Laurence seated himself heavily upon the dragon’s foreleg, grateful, and read the letter over again so he might at least have the pleasure of being unhappy with those whose unhappiness he had caused.

“I am sorry, Laurence; I do not suppose he could have heard that your fortune was restored,” Temeraire said, looking over at the wagon-cart, still piled high.

“He would have known me restored to the list,” Laurence said, but this was only a sop to Temeraire’s feelings. He knew that neither his fortune, nor his pardon and the reinstatement of his rank, which might restore him in the good graces of the world, would have weighed at all with Lord Allendale. That gentlemen could more easily have brooked his son’s public execution, on a charge he knew to be false, than to see his son laureled with gold and praised in every corner, and known to him as a traitor.

He might have told his father that worldly concerns at least had not weighed with him; he had acted only as his conscience had brutally required. But he had not seen his father since his conviction; he had not presumed to write, even after his sentence had been commuted to transportation, nor since his pardon. And they would now never speak again. There would be no opportunity for defense or explanation.

And Laurence could not but regard Temeraire’s extravagant hoard with dismay, although the Russians had been more astonished by his being willing to return any part of the treasure than by his keeping it entirely for himself. Laurence had asked how and where they should surrender the pillaged goods; the other aviators had only stared uncomprehending, and asked how he had managed to persuade Temeraire to surrender even the Tsar’s paintings, which could not have had a plainer provenance. He knew perfectly well what his father would have thought of a fortune obtained with so little character of law to the process.

But there was something too much like bitterness in that thought. Laurence made himself fold up the letter, and put it away in his pocket. He would not dwell upon what he could not repair. They were still at war; the French Emperor might have escaped, but the French army was yet strung out between Vilna and Berlin, what was left of it, and there would surely be more work to do soon enough.

There were other letters; letters from Spain: one from Jane Roland and one from Granby, with an enclosure addressed to Temeraire directly. Laurence meant to open them, but Temeraire said tentatively, “Laurence, I suppose you must begin to dress: Hammond will be calling for you in a quarter of an hour. Roland,” he called, “will you pray bring out Laurence’s robes? Be sure you do not track them in the dirt.”

Too late, Laurence recalled the conversation he had not attended; too late, protest sprang to his lips. Emily Roland was already with great ceremony and satisfaction unfolding the immense and heavily embroidered robes of silk which belonged to the son of the Emperor of China, and not to that of Lord Allendale.

When Laurence had gone, Temeraire brooded, watching the celebrations get under way. Even the magnificent display of fireworks which opened the evening did not please him: a stand of trees blocked a great deal of the covert’s view, which he felt might have been taken into account, and the faint drifting smoke only reminded him that he and every other dragon had eaten nothing but porridge and burnt horse for months.

“And it is not as though they did not know any better, anymore,” Temeraire said resentfully. He had refrained from making any remarks, while Laurence might be distressed by them any further, but after he had left for the celebration, Temeraire could no longer restrain himself. “It is not as though they had not seen, for themselves, that dragons should like to eat well, or live in a more orderly fashion; they have seen the arrangements of the Chinese legions.”

Churki, Hammond’s dragon—or rather, the Incan dragon who had decided, quite unaccountably in Temeraire’s opinion, to lay claim to him; Hammond by no means wished to be an aviator, nor even liked to fly—lifted her head out of her ruffled-up feathers; she had huddled down to await his return. “Why do you keep complaining we have not been invited to that ceremony? Plainly it is a gathering of men: how could any dragon come into that building where they are holding it?”

“They might make buildings large enough for us to come into, as they do in China,” Temeraire said, but she only huffed in a dismissive way.

“It is inconvenient for people to always be in buildings built to our size; it means they have too far to go to get from one thing to another,” Churki said, which had not occurred to Temeraire before. “Naturally they like to have places of their own; there is nothing wrong in that, nor that they should hold their own celebrations. And as far as I can tell, you are the senior dragon here; who else should be offering thanks for victory, and arranging the comforts of your troops, but you?”

“Oh,” Temeraire said, abashed. “But how am I to arrange any comforts, when we are only thrown upon a miserable covert, and have nowhere else to go?”

Churki shrugged. “This does seem a poor city,” she said, “and there are no large plazas of stone where dragons would ordinarily sleep or gather; but something may always be contrived! There is good enough timber in those woods there, and it would not be more than a few days to put down a floor of split logs, if you sent all those Russians to fetch a few dozen. Then you must pay men and women, if you have not enough in your own ayllu to carry out the work, to prepare ornaments and a feast. I do not see that there is any great puzzle about it,” she added, rather severely.

“Well,” Temeraire said, and would have protested that the woods were certainly property belonging to someone or another, but he could not help feeling it would be really complaining, then; the sort of complaining that shirkers did, when they did not want to work. Laurence had a great disgust of shirkers. “Ferris,” he called instead. “Will you be so good as to go into town for me, and make some inquiries? And pray can you see where Grig has got to?”

The crush of the ballroom would have been sufficient to stifle a man wearing something other than heavy silk robes. Laurence endured grimly both the heat and the attentions of the company. The robes were meant for a man presumed by their makers to be the natural center of any gathering he attended, and in this setting they had the happy power of ensuring him that position; he certainly outshone every man present, and most of the women. Hammond was aglow with delight, presenting him without hesitation to men of the highest rank as their social equal, and presuming upon the association to address himself to them. Laurence could not even check him, in public as they were, when Hammond was the King’s representative.

And the solitary one here, even though he was not even properly an envoy to Russia at all, but to China—but no other British diplomat had managed to keep up with the Tsar during the tumult of both retreat and pursuit. Lord Cathcart had been forced to flee St. Petersburg early on when Napoleon’s army had seized it; the ambassador in Moscow had decamped that city shortly before its fall, and Laurence had no idea what had become of the man. Only Hammond, with the benefit of a dragon as traveling-companion, had been able to stay with headquarters all the long dusty way.

“I am entirely reconciled to Churki’s company—entirely; I cannot overstate the benefits of having made myself so familiar, to the Tsar and his staff,” Hammond said, in low voice but with a naked delight that Laurence could not help but regard askance. “And, quite frankly, they think all the better of me, for being as they suppose her master; they value nothing so much as courage, and I assure you, Captain, that whenever we have caught them up, and I have been seen dismounting her back, and instructing her to go to her rest, without benefit of bit or harness, I have been received with a most gratifying amazement. I have arranged to have it happen in sight of the Tsar three times.”

Laurence could not openly say what he felt about such machinations, or about Hammond saying, “My dear Countess Lieven, pray permit me to make you known to His Imperial Highness.” He could only do his best to escape. A storm of cheering offered him an opportunity at last: the Tsar making his entrance to the pomp of a military band, and soldiers strewing the path that cleared for him with prizes: French standards, many torn and bloodstained, symbols of victory. Laurence managed to slip Hammond’s traces and take himself out onto a balcony. The night air, still bitterly cold, was for once welcome. He would have been glad to leave entirely.

“Ha, what a get-up,” General Kutuzov said, coming onto the balcony with him, surveying Laurence’s robes.

“Sir,” Laurence said, with a bow, sorry he could not defend himself against any such remark.

“Well, I hear you can afford them,” Kutuzov said, only heaping up the coals. “I have not heard so much gnashing of teeth in my life as when you brought that wagon-load of gold into camp, and all the rest of those big beasts nursing along scraps of silver, over which they nearly quarreled themselves to pieces. Tell me, do you think we could buy off these ferals with trinkets?”

“Not while they are starving,” Laurence said.

Kutuzov nodded with a small sigh, as if this was no more than he expected. There was a bench set upon the balcony. The old man sat down and brought his pipe out; he tamped down tobacco and lit it, puffing away clouds into the cold. They remained in silence. The revelry behind them was only increasing in volume. Outside on the street, on the other side of the back wall around the governor’s palace, a single shambling figure limped alone through a small pool of yellow lamp-light, leaving a trail dragged through the snow behind him: a French soldier draped in rags, occasionally stopping to emit a dry, hacking cough; dying of typhus. He continued his slow progress and disappeared back into the dark.

“So Napoleon has got away,” Kutuzov said.

“For the moment,” Laurence said. “I believe, sir, that the Tsar is determined on pursuit?”

Kutuzov sighed deeply from his belly, around the stem of the pipe. “Well, we’ll see,” he said. “It’s good to have your own house in order before you start arranging someone else’s. There are a thousand wild dragons on the loose between St. Petersburg and Minsk, and they aren’t going to pen themselves up.”

“I had hoped, sir, that you had thought better of that practice,” Laurence said.

“Half my officers are of the opinion we should bait them with poison and hunt them all down. Well, what do you expect, when they are flying around eating everything in sight, and sometimes people? But cooler heads know we can’t afford it! If it weren’t for you and those Chinese beasts, Napoleon would have had us outside Moscow last summer, and we wouldn’t be here to chat about it.” Kutuzov shook his head. “But one way or another, something must be done about them. We can’t rebuild the army when our supply-lines are being raided every day. You’ll forgive me for being a blunt old man, Captain,” he added, “but while I can see why you British would like us to finish beating Napoleon to pieces, I don’t see much good in it for Mother Russia at present.”

Laurence had already heard this sentiment murmured among some of the Russian soldiers; he was all the more sorry to hear it espoused by Kutuzov himself, the garlanded general of the hour. “You cannot suppose, sir, that Napoleon will be quieted for long, even by this disaster.”

“He may have enough else to occupy him,” Kutuzov said. “There was a coup attempt in Paris, you know.”

“I had not heard it,” Laurence said, taken aback.

“Oh, yes,” Kutuzov said. “Two weeks ago. That is why his Incan beasts went racing off home—back to that Empress of theirs. She seems to have managed everything neatly enough: all the men involved were rounded up and shot before the week was out. But Bonaparte is going to be busy enough at home for some time, I expect. Anyway, as long as he doesn’t come back to Russia, I don’t see that it’s our business to worry about him. If the Prussians and Austrians don’t like their neighbor, let them do something about him.”

At this juncture, Hammond appeared to retrieve Laurence and draw him back into the ballroom; he was worried and yet unsurprised when Laurence related the substance of the conversation to him. “I am afraid far too many of the Russian generals are of like mind,” Hammond said. “But thank Heaven! The Tsar, at least, is not so shortsighted; you may imagine, Captain, how profoundly he has been affected by the misery and suffering which Bonaparte has inflicted upon his nation. Indeed he would like a word with you, Captain, if you will come this way—”

Laurence submitted to his doom, and permitted Hammond to usher him up to the dais where the Tsar now sat in state; but when they had approached the Tsar rose and came down the steps, much to Laurence’s dismay, and kissed him on both cheeks. “Your Highness,” the Tsar said, “I am delighted to see you look so well. Come, let us step outside a moment.”

This was too much; Laurence opened his mouth to protest that he was by no means to be treated as royalty; but Hammond cleared his throat with great vigor to prevent him, and the Tsar was already leading the way into an antechamber, advisors trailing him like satellites after their Jovian master. “Clear the hallway outside, Piotr,” the Tsar said to a tall young equerry, as they came into the smaller room. “Your Highness—”

“Your Majesty,” Laurence broke in, unable to bear it, despite Hammond’s looks, “I beg your pardon. I am foremost a British serving-officer, and a captain of the Aerial Corps; I am far from meriting that address.”

But Alexander did not bend. “You may not desire the burden which it represents, but you must endure it. The Tsar of Russia cannot be so uncouth as to insult the emperor who chose to bestow that honor upon you.” Nor, Laurence unwillingly recognized, be so unwise as to insult an emperor who could send three hundred dragons to Moscow; he bowed in acknowledgment and was silent.

“We will take a little air together,” Alexander said. “You know Count Nesselrode, I think, Mr. Hammond?”

Hammond stammered agreement, even as he cast an anxious sideways glance at that gentleman, who certainly meant to begin issuing demands as soon as his Imperial master was out of ear-shot of haggling: demands for money, which Hammond was far from being authorized to meet on Britain’s behalf. But Laurence could do nothing to relieve his discomfiture. He followed the Tsar out upon the balcony.

A greater contrast with the scene which he had overlooked, from the other side of the palace, could scarcely be envisioned: the streets before the palace gates were thronged with celebrating Russian soldiers, shouting, screams of laughter, a blaze of lanterns, and even the occasional squib of makeshift fireworks contrived from gunpowder. Alexander looked with pardonable satisfaction upon his troops, who had pursued Napoleon across five hundred barren miles in winter, and yet remained in fighting order.

“I trust you were not put to excessive trouble to return the portraits, Your Highness,” the Tsar said. “I was given to understand it quite impossible to extract prizes from the beasts, once taken.”

“By no means, Your Majesty,” Laurence said. “I must assure you that dragons, while having no more natural understanding of property rights than would a wholly uneducated man, may be brought to an equal comprehension; Temeraire was entirely willing,” this a slight exaggeration, “to restore all the stolen property to its rightful owners, if only provenance might be established.” Laurence paused; he disliked very much making use of an advantage he had not earned, but the opportunity of putting a word into so important an ear could not be given up. “It is a question of education and of management, if you will pardon my saying so. If a dragon is taught to value nothing but gold, and to think of its own worth as equal to that of its hoard, it will naturally disdain both discipline and law in the pursuit of treasure.”

But Alexander only nodded abstractly, without paying him much attention. “I believe you were speaking with good Prince Kutuzov, earlier this evening,” he said, surprising Laurence; he wondered how the Tsar should already have intelligence of an idle conversation, held not an hour since, in the midst of his ball. “I am sorry to have dragged him so far from his warm hearth. His old age deserved a better rest than his country—and Bonaparte!—have given him.”

Laurence spoke cautiously, feeling himself on the treacherous grounds of politics; did Alexander mean to criticize the old general’s views? “He has always seemed to me a great deal of a pragmatist, Your Majesty.”

“He is a wise old warrior,” Alexander said. “I have not many such men. And yet sometimes the wiser course requires such pains as may make even a wise man shrink from them. You, I am sure, understand that Bonaparte’s appetite is insatiable. He may lick his wounds awhile; but who that has seen the wreck of Moscow could imagine that the man who went on from that disaster to continue a futile pursuit will long be dismayed?”

The pursuit had not seemed nearly so futile at the time, to one among the prey. If Napoleon had been able to feed the Russian ferals for another week, if the Chinese legions had reached the end of their own supply a week earlier; on so narrow a thread had the outcome turned. But Laurence did not need to be persuaded of Napoleon’s recklessness. “No,” he said. “He will not stop.” Then slowly, he added, “He cannot stop. If his ambition was of a kind which could be checked by any form of caution, he would never have achieved his high seat. He does not know fear, I think; even when he should.”

Alexander turned to him, his face suddenly alight and intent. “Exactly so!” he cried. “You have described him exactly. A man who does not know fear—even of God. Once even I permitted myself to be lost in admiration of his genius; I will not deny it, though I have learned to be ashamed of it. And yet at that time, it seemed to me such courage, such daring, demanded respect. But now we have seen him for what he is; in the ruin of his army he has been revealed: a fiend who gorges on human blood and misery! If only we had captured him!”

“I am very sorry he should have escaped,” Laurence said, low.

He had tried to comfort himself, after the first bitter disappointment, with common sense: Bonaparte would surely not have left himself exposed in any way that might have rendered him vulnerable to capture. He had undoubtedly crossed with a strong company, in good order, and remained always in the very heart of his Old Guard. There had not been any real chance. But common sense was insufficient relief; Laurence feared Alexander was too right, when he said that Napoleon would not be checked for long. He would raise a fresh army, the drum-beat would begin again. The Russian Army and the Russian winter had won them not a year’s reprieve.

“I am determined it will not be so,” Alexander said. “He may have slipped away; but we will not allow him to escape justice forever. God has granted us victory, and more than that, has left our enemy weakened. We must seize this opportunity of destroying his power. It is our duty to liberate not only Russia but all Europe from this scourge of mankind. I will pursue him; I will see him brought down! When my soldiers stand in Paris, as his trampled into Petersburg and Moscow, then I will be satisfied to go home again; not before!”

Alexander’s face was flushed with vehemence. Laurence regarded the Tsar soberly. It was impossible to doubt the sincerity of his inspired wrath. But the Tsar spoke not of forcing Napoleon to sue for peace, or make concessions of territory; he spoke of driving Napoleon from his throne. To take Paris—the very idea was fantastical. All of Prussia yet lay under the yoke of France; Austria was docile and shrinking before him; and Napoleon would surely defend the heartland of France desperately, with every resource in his power—which, Laurence well knew, included a vast and devoted army of dragons. And behind them, the greatest cities of Russia lay in rubble and in ruin; feral dragons roamed the countryside pillaging at will. Kutuzov’s might be the loudest voice, but it would not be the only one advising Alexander to go home and put his own house in order.

“Well,” Hammond said, as they left the palace together, a little while after, “I suppose I will either be knighted, or sent to prison; I have left the Government very few alternatives.”

Laurence regarded him with concern. “What have you promised the Russians?”

“A million pounds,” Hammond said.

“Good God!” Laurence said, appalled. “Hammond, what authority have you to offer a tenth such a sum?”

“Oh—” Hammond gestured impatiently. “I am overstepping my orders, but the plain truth is, it cannot be done with less; likely it must be twice as much. Their finances are in the most monstrous wreck imaginable.”

“That, I can well believe,” Laurence said. “Can it be done at all?”

“I am not going to tempt fate by making any such prediction,” Hammond said. “Bonaparte has overturned too many thrones and armies. But I will say—if it is ever to be done, it must be done now. He has been pushed over the Niemen already; Wellington is ready to strike in Spain. We will not get a better chance. But if we are to get anywhere at all, we must bring the Prussians over; and to do that, we must empower the Russians to make a real showing. I will call it cheap at the price, if a million pounds should have that effect.”

Hammond concluded almost defiantly, as if he were making an argument before the king’s ministers, rather than in a half-deserted street in Vilna, before a man nowhere in their good graces. Laurence shook his head.

“Sir,” he said, “I think you have forgotten one critical point. Can you conceive that the King of Prussia should ever agree to join us in opposing Bonaparte while his son and heir remains hostage in Paris?”

Hammond said, “His officers will force him to it. All of East Prussia longs to throw off Bonaparte’s yoke. A few Russian victories, and his own generals will be ready to mutiny to our side if he does not embrace the effort—”

“And then what do you imagine will happen to the prince?” Laurence snapped; Hammond paused, as if so minor a consideration had not occurred to him.

“Bonaparte cannot mean to offer any harm to the boy,” Hammond said, uneasily.

“His father may be less willing to rely upon such a conviction,” Laurence said.