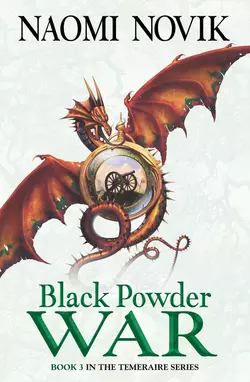

Black Powder War

Naomi Novik

Naomi Novik’s stunning series of novels follow the global adventures of Captain William Laurence and his fighting dragon Temeraire as they are thrown together to fight for Britain during the turbulent time of the Napoleonic Wars.British flyer Will Laurence and his extraordinary Celestial dragon, Temeraire, gratefully anticipate their voyage home from China. But before they set sail, they are waylaid by urgent new orders. The British Government, having purchased three valuable dragon eggs from the Ottoman Empire – one of a rare fire-breathing Kazilik dragon, one of the most deadly breeds in existence – now require Laurence and Temeraire to make a more perilous overland journey instead, stopping off in Istanbul to collect and escort the precious cargo back to England.And time is of the essence if the eggs are to hatch upon British shores.A cross-continental expedition is a daunting prospect, fraught with countless dangers. The small party must be prepared to travel the treacherous Silk Road: navigating frigid mountain passes and crossing sterile deserts to evade feral dragon attacks and Napoleon's aggressive infantry.Barely surviving the poisonous intrigue of the Ottoman Court, the small British party's journey home is delayed once more. The Prussians muster their forces before them, barring their way, and Laurence and Temeraire become swept up in the battle against Bonaparte – trapped by politics as they learn that the British had promised to send their allies aid – but help is months overdue.The crew will also face unexpected menace, for a Machiavellian herald precedes them, spreading political poison in her wake. Lien, the white celestial dragon, absconded from the Chinese Imperial Court shortly after the humiliating death of her beloved princely companion. Fervently believing Temeraire to be the architect of her anguish, she has vowed to ally herself with his greatest enemy in order to exact a full and painful revenge upon everything and everyone the black dragon holds dear.

NAOMI NOVIK

Temeraire: Black Powder War

Dedication (#ulink_b0bcc8a3-f237-599a-bdf1-a23ee0ed039b)

for my mother

in small return for many bajki cudowne

Contents

Cover (#ufcaa8717-0f65-5c2e-8ce6-dd4e357996c0)

Title Page (#u8fc210f3-73d8-5353-833b-5b3158457fb7)

Dedication (#ulink_853bc4c3-0b37-54a2-beeb-47f5762ef163)

Prologue (#ulink_1a740d29-1fb5-5ded-bd02-74eeb85b3bae)

Part I (#ulink_a7007593-ffee-5aac-8467-3d479a012774)

Chapter One (#ulink_4d7509ad-cae3-5e5b-9ec5-a7e5df15e648)

Chapter Two (#ulink_5b2edc53-71f2-5303-9f3d-9a39ed0b61df)

Chapter Three (#ulink_471ad6bb-577d-53b6-aed4-a3c3545eb2fe)

Chapter Four (#ulink_bdaaca40-caa9-52b7-a4b3-a0bdd139a3c8)

Chapter Five (#litres_trial_promo)

Part II (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Six (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Ten (#litres_trial_promo)

Part III (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eleven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twelve (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fourteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Sixteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seventeen (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Prologue (#ulink_bec8d87a-8378-5511-96b1-324e7460c499)

Even looking into the gardens at night, Laurence could not imagine himself home; too many bright lanterns looking out from the trees, red and gold under the upturned roof-corners; the sound of laughter behind him like a foreign country. The musician had only one string to his instrument, and he called from it a wavering, fragile song, a thread woven through the conversation which itself had become nothing more than music: Laurence had acquired very little of the language, and the words soon lost their meaning for him when so many voices joined in. He could only smile at whomever addressed him and hide his incomprehension behind the cup of tea of palest green, and at the first chance he stole quietly away around the corner of the terrace. Out of sight, he put his cup down on the window-sill half-drunk; it tasted to him like perfumed water, and he thought longingly of strong black tea full of milk, or better yet of coffee; he had not tasted coffee in two months.

The moon-viewing pavilion was set on a small promontory of rock jutting from the mountain-side, high enough to give an odd betwixt-and-between view of the vast imperial gardens laid out beneath: neither as near the ground as an ordinary balcony nor so high above as Temeraire’s back, where trees changed into matchsticks and the great pavilions into children’s toys. He stepped out from under the eaves and went to the railing: there was a pleasant coolness to the air after the rain, and Laurence did not mind the damp, the mist on his face welcome and more familiar than all the rest of his surroundings, from years at sea. The wind had obligingly cleared away the last of the lingering storm-bank; now steam curled languidly upon the old, soft, rounded stones of the pathways, slick and grey and bright under a moon nearly three-quarters full, and the breeze was full of the smell of over-ripe apricots, which had fallen from the trees to smash upon the cobbles.

Another light was flickering among the stooped ancient trees, a thin white gleam passing behind the branches, now obscured, now seen, moving steadily towards the shore of the nearby ornamental lake, and with it the sound of muffled footfalls. Laurence could not see very much at first, but shortly a queer little procession came out into the open: a scant handful of servants bowed down under the weight of a plain wooden bier and the shrouded body lying atop; and behind them trotted a couple of young boys, carrying shovels and throwing anxious looks over their shoulders.

Laurence stared, wondering; and then the tree-tops all gave a great shudder and yielded to Lien, pushing through into the wide clearing behind the servants, her broad-ruffed head bowed down low and her wings pinned tight to her sides. The slim trees bowed out of her way or broke, leaving long strands of willow-leaves draped across her shoulders. These were her only adornment: all her elaborate rubies and gold had been stripped away, and she looked pale and queerly vulnerable with no jewels to relieve the white translucence of her colour-leached skin; in the darkness, her scarlet eyes looked black and hollow.

The servants set down their burden to dig a hole at the base of one old majestic willow-tree, blowing out great sighs here and again as they flung the soft dirt up, and leaving black streaks upon their pale broad faces as they laboured and sweated. Lien paced slowly around the circumference of the clearing, bending to tear up some small saplings that had taken root at the edges, throwing the straight young trees into a heap. There were no other mourners present, save one man in dark blue robes trailing after Lien; there was a suggestion of familiarity about him, his walk, but Laurence could not see his face. The man took up a post at the side of the grave, watching silently as the servants dug; there were no flowers, nor the sort of long funerary procession Laurence had before witnessed in the streets of Peking: family tearing at their clothes, shaven-headed monks carrying censers and spreading clouds of incense. This curious night-time affair might almost have been the scene of a pauper’s burial, save for the gold-roofed imperial pavilions half-hidden among the trees, and Lien standing over the proceedings like a milk-white ghost, vast and terrible.

The servants did not unwrap the body before setting it in the ground; but then it had been more than a week since Yongxing’s death. This seemed a strange arrangement for the burial of an imperial prince, even one who had conspired at murder and meant to usurp his brother’s throne; Laurence wondered if his burial had earlier been forbidden, or perhaps was even now clandestine. The small shrouded body slipped out of view, a soft thump following; Lien keened once, almost inaudibly, the sound creeping unpleasantly along the back of Laurence’s neck and vanishing in the rustling of the trees. He felt abruptly an intruder, though likely they could not see him amid the general blaze of the lanterns behind him; and to go away again now would cause the greater disturbance.

The servants had already begun to fill in the grave, scraping the heaped earth back into the hole in broad sweeps, work that went quickly; soon the ground was patted level once again under their shovels, nothing to mark the grave-site but the raw denuded patch of ground and the low-hanging willow tree, its long trailing branches sheltering the grave. The two boys went back into the trees to gather armfuls of forest-cover, old rotted leaves and needles, which they spread all over the surface until the grave could not be told from the undisturbed ground, vanishing entirely from view. This labour accomplished, they stood uncertainly back: without an officiate to give the affair some decent ceremony, there was nothing to guide them. Lien gave them no sign; she had huddled low to the ground, drawn in upon herself. At last the men shouldered their spades and drifted away into the trees, leaving the white dragon as wide a berth as they could manage.

The man in blue robes stepped to the graveside and made the sign of the cross over his chest: turning away his face came full into the moonlight, and abruptly Laurence knew him: De Guignes, the French ambassador, and almost the most unlikely mourner imaginable. Yongxing’s violent antipathy towards the influence of the West had known no favourites, nor made distinctions between French, British, and Portuguese, and De Guignes would never have been admitted to the prince’s confidence in life, nor his company tolerated by Lien. But there were the long aristocratic features, wholly French; his presence was at once unmistakable and unaccountable. De Guignes lingered yet a moment in the clearing and spoke to Lien: inaudible at the distance, but a question by his manner. She gave him no answer, made no sound at all, crouched low with her gaze fixed only upon the hidden grave, as if she would imprint the place upon her memory. After a moment he bowed himself away gracefully and left her.

She stayed unmoving by the grave, striped by scudding clouds and the lengthening shadows of the trees. Laurence could not regret the prince’s death, yet pity stirred; he did not suppose anyone else would have her as companion now. He stood watching her for a long time, leaning against the rail, until the moon travelled at last too low and she was hidden from view. A fresh burst of laughter and applause came around the terrace corner: the music had wound to a close.

I (#ulink_ab84cee6-a1e7-5da3-960e-13047e13c799)

Chapter One (#ulink_6bab8733-758f-5cd3-bc75-044ab46a5622)

The hot wind blowing into Macau was sluggish and unrefreshing, only stirring up the rotting salt smell of the harbour, the fish corpses and great knots of black-red seaweed, the effluvia of human and dragon wastes. Even so the sailors were sitting crowded along the rails of the Allegiance for a breath of the moving air, leaning against one another to get a little room. A little scuffling broke out among them from time to time, a dull exchange of shoving back and forth, but these quarrels died almost at once in the punishing heat.

Temeraire lay disconsolately upon the dragondeck, gazing towards the white haze of the open ocean, the aviators on duty lying half-asleep in his great shadow. Laurence himself had sacrificed dignity so far as to take off his coat, as he was sitting in the crook of Temeraire’s foreleg and so concealed from view.

‘I am sure I could pull the ship out of the harbour,’ Temeraire said, not for the first time in the past week; and sighed when this amiable plan was again refused: in a calm he might indeed have been able to tow even the enormous dragon transport, but against a direct headwind he could only exhaust himself to no purpose.

‘Even in a calm you could scarcely pull her any great distance,’ Laurence added consolingly. ‘A few miles may be of some use out in the open ocean, but at present we may as well stay in harbour, and be a little more comfortable; we would make very little speed even if we could get her out.’

‘It seems a great pity to me that we must always be waiting on the wind, when everything else is ready and we are also,’ Temeraire said. ‘I would so like to be home soon: there is so very much to be done.’ His tail thumped hollowly upon the boards, for emphasis.

‘I beg you will not raise your hopes too high,’ Laurence said, himself a little hopelessly: urging Temeraire to restraint had so far not produced any effect, and he did not expect a different event now. ‘You must be prepared to endure some delays; at home as much as here.’

‘Oh! I promise I will be patient,’ Temeraire said, and immediately dispelled any small notion Laurence might have had of relying upon this promise by adding, unconscious of any contradiction, ‘but I am quite sure the Admiralty will see the justice of our case very quickly. Certainly it is only fair that dragons should be paid, if our crews are.’

Having been at sea from the age of twelve onwards, before the accident of chance which had made him the captain of a dragon rather than a ship, Laurence enjoyed an extensive familiarity with the gentlemen of the Admiralty Board who oversaw the Navy and the Aerial Corps both, and a keen sense of justice was hardly their salient feature. The offices seemed rather to strip their occupants of all ordinary human decency and real qualities: creeping, nip-farthing political creatures, very nearly to a man. The very superior conditions for dragons here in China had forced open Laurence’s unwilling eyes to the evils of their treatment in the West, but as for the Admiralty’s sharing that view, at least so far as it would cost the country tuppence, he was not sanguine.

In any case, he could not help privately entertaining the hope that once at home, back at their post on the Channel and engaged in the honest business of defending their country, Temeraire might, if not give over his goals, then at least moderate them. Laurence could make no real quarrel with the aims, which were natural and just; but England was at war, after all, and he was conscious, as Temeraire was not, of the impudence in demanding concessions from their own Government under such circumstances: very like mutiny. Yet he had promised his support and would not withdraw it. Temeraire might have stayed here in China, enjoying all the luxuries and freedoms which were his birthright, as a Celestial. He was coming back to England largely for Laurence’s sake, and in hopes of improving the lot of his comrades-in-arms; despite all Laurence’s misgivings, he could hardly raise a direct objection, though it at times felt almost dishonest not to speak.

‘It is very clever of you to suggest we should begin with pay,’ Temeraire continued, heaping more coals of fire onto Laurence’s conscience; he had proposed it mainly for its being less radical a suggestion than many of the others which Temeraire had advanced, such as the wholesale demolition of quarters of London to make room for thoroughfares wide enough to accommodate dragons, and the sending of draconic representatives to address Parliament, which aside from the difficulty of their getting into the building would certainly have resulted in the immediate flight of all the human members. ‘Once we have pay, I am sure everything else will be easier. Then we can always offer people money, which they like so much, for all the rest; like those cooks which you have hired for me. That is a very pleasant smell,’ he added, not a non sequitur: the rich smoky smell of well-charred meat was growing so strong as to rise over the stench of the harbour.

Laurence frowned and looked down: the galley was situated directly below the dragondeck, and wispy ribbons of smoke, flat and wide, were seeping up from between the boards of the deck. ‘Dyer,’ he said, beckoning to one of his runners, ‘go and see what they are about, down there.’

Temeraire had acquired a taste for the Chinese style of dragon cookery which the British quartermaster, expected only to provide freshly butchered cattle, was quite unable to satisfy, so Laurence had found two Chinese cooks willing to leave their country for the promise of substantial wages. The new cooks spoke no English, but they lacked nothing in self-assertion; already professional jealousy had nearly brought the ship’s cook and his assistants to pitched battle with them over the galley stoves, and produced a certain atmosphere of competition.

Dyer trotted down the stairs to the quarterdeck and opened the door to the galley: a great rolling cloud of smoke came billowing out, and at once there was a shout and halloa of ‘Fire!’ from the lookouts up in the rigging. The watch-officer rang the bell frantically, the clapper scraping and clanging; Laurence was already shouting, ‘To stations!’ and sending his men to their fire crews.

All lethargy vanished at once, the sailors running for buckets, pails; a couple of daring fellows darted into the galley and came out dragging limp bodies: the cook’s mates, the two Chinese, and one of the ship’s boys, but no sign of the ship’s cook himself. Already the dripping buckets were coming in a steady flow, the bosun roaring and thumping his stick against the foremast to give the men the rhythm, and one after another the buckets were emptied through the galley doors. But still the smoke came billowing out, thicker now, through every crack and seam of the deck, and the bitts of the dragon-deck were scorching hot to the touch: the rope coiled over two of the iron posts was beginning to smoke.

Young Digby, quick-thinking, had organized the other ensigns: the boys were hurrying together to unwind the cable, swallowing hisses of pain when their fingers brushed against the hot iron. The rest of the aviators were ranged along the rail, hauling up water in buckets flung over the side and dousing the dragondeck: steam rose in white clouds and left a grey crust of salt upon the already warping planks, the deck creaking and moaning like a crowd of old men. The tar between the seams was liquefying, running in long black streaks along the deck with a sweet, acrid smell as it scorched and smoked. Temeraire was standing on all four legs now, mincing from one place to another for relief from the heat, though Laurence had seen him lie with pleasure on stones baked by the full strength of the midday sun.

Captain Riley was in and among the sweating, labouring men, shouting encouragement as the buckets swung back and forth, but there was an edge of despair in his voice. The fire was too hot, the wood seasoned by the long stay in harbour under the baking heat; and the vast holds were filled with goods for the journey home: delicate china wrapped in dry straw and packed in wooden crates, bales of silks, new-laid sailcloth for repairs. The fire had only to make its way four decks down, and the stores would go up in quick hot flames running all the way back to the powder magazine, and carry her all away.

The morning watch, who had been sleeping below, were now fighting to come up from the lower decks, open-mouthed and gasping with the smoke chasing them out, breaking the lines of water-carriers in their panic: though the Allegiance was a behemoth, her forecastle and quarterdeck could not hold her entire crew, not with the dragondeck nearly in flames. Laurence seized one of the stays and pulled himself up on the railing of the deck, looking for his crew among the milling crowd: most had already been out upon the dragondeck, but a handful remained unaccounted for: Therrows, his leg still in splints after the battle in Peking; Keynes, the surgeon, likely at his books in the privacy of his cabin; and he could see no sign of Emily Roland, his other runner: she was scarcely turned eleven, and could not easily have pushed her way out past the heaving, struggling men.

A thin, shrill kettle-whistle erupted from the galley chimneys, the metal cowls beginning to droop towards the deck, slowly, like flowers gone to seed. Temeraire hissed back in instinctive displeasure, drawing his head back up to all the full length of his neck, his ruff flattening against his neck. His great haunches had already tensed to spring, one foreleg resting on the railing. ‘Laurence, is it quite safe for you there?’ he called anxiously.

‘Yes, we will be perfectly well, go aloft at once,’ Laurence said, even as he waved the rest of his men down to the forecastle, concerned for Temeraire’s safety with the planking beginning to give way. ‘We may better be able to come at the fire once it has come up through the deck,’ he added, principally for the encouragement of those hearing him; in truth, once the dragondeck fell in, he could hardly imagine they would be able to put out the blaze.

‘Very well, then I will go and help,’ Temeraire said, and took to the air.

A handful of men less concerned with preserving the ship than their own lives had already lowered the jolly-boat into the water off the stern, hoping to make their escape unheeded by the officers engaged in the desperate struggle against the fire; they dived off in panic as Temeraire unexpectedly darted around the ship and descended upon them. He paid no attention to the men, but seized the boat in his talons, ducked it underwater like a ladle, and heaved it up into the air, dripping water and oars. Carefully keeping it balanced, he flew back and poured it out over the dragondeck: the sudden deluge went hissing and spitting over the planks, and tumbled in a brief waterfall over the stairs and down.

‘Fetch axes!’ Laurence called urgently. It was desperately hot, sweating work, hacking at the planks with steam rising and their axe blades skidding on the wet and tar-soaked wood, smoke pouring out through every cut they made. All struggled to keep their footing each time Temeraire deluged them once again; but the constant flow of water was the only thing that let them keep at their task, the smoke otherwise too thick. As they laboured, a few of the men staggered and fell unmoving upon the deck: no time even to heave them down to the quarterdeck, the minutes too precious to sacrifice. Laurence worked side by side with his armourer, Pratt, long thin trails of black-stained sweat marking their shirts as they swung the axes in uneven turns, until abruptly the planking cracked with gunshot sounds, a great section of the dragondeck all giving way at once and collapsing into the eager hungry roar of the flames below.

For a moment Laurence wavered on the verge, then his first lieutenant, Granby, was pulling him away. They staggered back together, Laurence half-blind and nearly falling into Granby’s arms; his breath would not quite come, rapid and shallow, and his eyes were burning. Granby dragged him partway down the steps, and then another torrent of water carried them in a rush the rest of the way, to fetch up against one of the forty-two-pounder carronades on the forecastle. Laurence managed to pull himself up the railing in time to vomit over the side, the bitter taste in his mouth still less strong than the acrid stink of his hair and clothes.

The rest of the men were abandoning the dragondeck, and now the enormous torrents of water could go straight down at the flames. Temeraire had found a steady rhythm, and the clouds of smoke were already less: black sooty water was running out of the galley doors onto the quarterdeck. Laurence felt queerly shaken and ill, heaving deep breaths that did not seem to fill his lungs. Riley was rasping out hoarse orders through the speaking trumpet, barely loud enough to be heard over the hiss of smoke; the bosun’s voice was gone entirely: he was pushing the men into rows with his bare hands, pointing them at the hatchways; soon there was a line organized, handing up the men who had been overcome or trampled below: Laurence was glad to see Therrows being lifted out. Temeraire poured another torrent upon the last smouldering embers; then Riley’s coxswain Basson poked his head out of the main hatch, panting, and shouted, ‘No more smoke coming through, sir, and the planks above the berth-deck ain’t worse than warm: I think she’s out.’

A heartfelt ragged cheer went up. Laurence was beginning to feel he could get his wind back again, though he still spat black with every coughing breath; with Granby’s hand he was able to climb to his feet. A haze of smoke like the aftermath of cannon-fire lay thickly upon the deck, and when he climbed up the stairs he found a gaping charcoal fire-pit in place of the dragondeck, the edges of the remaining planking crisped like burnt paper. The body of the poor ship’s cook lay like a twisted cinder among the wreckage, skull charred black and his wooden legs burnt to ash, leaving only the sad stumps to the knee.

Having let down the jolly-boat, Temeraire hovered above uncertainly a little longer and then let himself drop into the water beside the ship: there was nowhere left for him to land upon her. Swimming over and grasping at the rail with his claws, he craned up his great head to peer anxiously over the side. ‘You are well, Laurence? Are all my crew all right?’

‘Yes; I have made everyone,’ Granby said, nodding to Laurence. Emily, her cap of sandy hair speckled grey with soot, came to them dragging a jug of water from the scuttlebutt: stale and tainted with the smell of the harbour, and more delicious than wine.

Riley climbed up to join them. ‘What a ruin,’ he said, looking over the wreckage. ‘Well, at least we have saved her, and thank Heaven for that; but how long it will take before we can sail now, I do not like to think.’ He gladly accepted the jug from Laurence and drank deep before handing it on to Granby. ‘And I am damned sorry; I suppose all your things must be spoiled,’ he added, wiping his mouth: senior aviators had their quarters towards the bow, one level below the galley.

‘Good God,’ Laurence said, blankly, ‘and I have not the least notion what has happened to my coat.’

‘Four; four days,’ the tailor said in his limited English, holding up fingers to be sure he had not been misunderstood; Laurence sighed and said, ‘Yes, very well.’ It was small consolation to think that there was no shortage of time: two months or more would be required to repair the ship, and until then he and all his men would be cooling his heels on shore. ‘Can you repair the other?’

They looked together down at the coat which Laurence had brought him as a pattern: more black than bottle-green now, with a peculiar white residue upon the buttons and smelling strongly of smoke and salt water both. The tailor did not say no outright, but his expression spoke volumes. ‘You take this,’ he said instead, and going into the back of his workshop brought out another garment: not a coat, precisely, but one of the quilted jackets such as the Chinese soldiers wore, like a tunic opening down the front, with a short upturned collar.

‘Oh, well—’ Laurence eyed it uneasily; it was made of silk, in a considerably brighter shade of green, and handsomely embroidered along the seams with scarlet and gold: the most he could say was that it was not as ornate as the formal robes to which he had been subjected on prior occasions.

But he and Granby were to dine with the commissioners of the East India Company that evening; he could not present himself half-dressed, or keep himself swathed in the heavy cloak which he had put on to come to the shop. He was glad enough to have the Chinese garment when, returning to his new quarters on shore, Dyer and Roland told him there was no proper coat to be had in town for any money whatsoever: not very surprising, as respectable gentlemen did not choose to look like aviators, and the dark green of their broadcloth was not a popular colour in the Western enclave.

‘Perhaps you will set a new fashion,’ Granby said, somewhere between mirth and consolation; a lanky fellow, he was himself wearing a coat seized from one of the hapless midwingmen, who having been quartered on the lower decks had not suffered the ruin of their own clothes. With an inch of wrist showing past his coat sleeves and his pale cheeks as usual flushed with sunburn, he looked at the moment rather younger than his twenty years and six, but at least no one would look askance. Laurence, being a good deal more broad-shouldered, could not rob any of the younger officers in the same manner, and though Riley had handsomely offered, Laurence did not mean to present himself in a blue coat, as if he were ashamed of being an aviator and wished to pass himself off as still a naval captain.

He and his crew were now quartered in a spacious house set directly upon the waterfront, the property of a local Dutch merchant more than happy to let it to them and remove his household to apartments farther into the town, where he would not have a dragon on his doorstep. Temeraire had been forced by the destruction of his dragondeck to sleep on the beach, much to the dismay of the Western inhabitants; to his own disgust as well, the shore being inhabited by small and irritating crabs which persisted in treating him like the rocks in which they made their homes and attempting to conceal themselves upon him while he slept.

Laurence and Granby paused to bid him farewell on their way to the dinner. Temeraire, at least, approved Laurence’s new costume; he thought the shade a pretty one, and admired the gold buttons and thread particularly. ‘And it looks handsome with the sword,’ he added, having nosed Laurence around in a circle the better to inspect him: the sword in question was his very own gift, and therefore in his estimation the most important part of the ensemble. It was also the one piece for which Laurence felt he need not blush: his shirt, thankfully hidden beneath the coat, not all the scrubbing in the world could save from disgrace; his breeches did not bear close examination; and as for his stockings, he had resorted to his tall Hessian boots.

They left Temeraire settling down to his own dinner under the protective eyes of a couple of midwingmen and a troop of soldiers under the arms of the East India Company, part of their private forces; Sir Thomas Staunton had loaned them to help guard Temeraire not from danger but overenthusiastic well-wishers. Unlike the Westerners who had fled their homes near the shore, the Chinese were not alarmed by dragons, living from childhood in their midst, and the tiny handful of Celestials so rarely left the Imperial precincts that to see one, and better yet to touch, was counted an honour and an assurance of good fortune.

Staunton had also arranged this dinner by way of offering the officers some entertainment and relief from their anxieties over the disaster, unaware that he would be putting the aviators to such desperate shifts in the article of clothing. Laurence had not liked to refuse the generous invitation for so trivial a reason, and had hoped to the last that he might find something more respectable to wear; now he came ruefully prepared to share his travails over the dinner table, and bear the amusement of the company.

His entrance was met with a polite if astonished silence, at first; but he had scarcely paid his respects to Sir Thomas and accepted a glass of wine before murmurs began. One of the older commissioners, a gentleman who liked to be deaf when he chose, said quite clearly, ‘Aviators and their starts; who knows what they will take into their heads next,’ which made Granby’s eyes glitter with suppressed anger; and a trick of the room made some less consciously indiscreet remarks audible also.

‘What do you suppose he means by it?’ inquired Mr. Chatham, a gentleman newly arrived from India, while eyeing Laurence with interest from the next window over; he was speaking in low voices with Mr. Grothing-Pyle, a portly man whose own interest was centred upon the clock, and in judging how soon they should go in to dinner.

‘Hm? Oh; he has a right to style himself an Oriental prince now if he likes,’ Grothing-Pyle said, shrugging, after an incurious glance over his shoulder. ‘And just as well for us too. Do you smell venison? I have not tasted venison in a year.’

Laurence turned his own face to the open window, appalled and offended in equal measure. Such an interpretation had never even occurred to him; his adoption by the Emperor had been purely and strictly pro forma, a matter of saving face for the Chinese, who had insisted that a Celestial might not be companion to any but a direct connection of the Imperial family; while on the British side it had been eagerly accepted as a painless means of resolving the dispute over the capture of Temeraire’s egg. Painless, at least, to everyone but Laurence, already in possession of one proud and imperious father, whose wrathful reaction to the adoption he anticipated with no small dismay. True, that consideration had not stopped him: he would have willingly accepted anything short of treason to avoid being parted from Temeraire. But he had certainly never sought or desired so signal and queer an honour, and to have men think him a ludicrous kind of social climber, who should value Oriental titles above his own birth, was deeply mortifying.

The embarrassment closed his mouth. He would have gladly shared the story behind his unusual clothing as an anecdote; as an excuse, never. He spoke shortly in reply to the few remarks offered him; anger made him pale and, if he had only known it, gave his face a cold, forbidding look, almost dangerous, which made conversation near him die down. He was ordinarily good-humoured in his expression, and though he was not darkly tanned, the many years labouring in the sun had given his looks a warm bronzed cast; the lines upon his face were mostly smiling: all the more contrast now. These men owed if not their lives, at least their fortunes to the success of the diplomatic mission to Peking, whose failure would have meant open warfare and an end to the China trade, and whose success had cost Laurence a blood-letting and the life of one of his men; he had not expected any sort of effusive thanks and would have spurned them if offered, but to meet with derision and incivility was something entirely different.

‘Shall we go in?’ Sir Thomas said, sooner than usual, and at the table he made every effort to break the uneasy atmosphere which had settled over the company: the butler was sent back to the cellar a half-dozen times, the wines growing more extravagant with each visit, and the food was excellent despite the limited resources accessible to Staunton’s cook: among the dishes was a very handsome fried carp, laid upon a ragout of the small crabs, now victims in their turn, and for centrepiece a pair of fat haunches of venison roasted, accompanied by a dish full of glowing jewel-red currant jelly.

The conversation flowed again; Laurence could not be insensible to Staunton’s real and sincere desire to see him and all the company comfortable, and he was not of an implacable temper to begin with; still less when encouraged with the best part of a glorious burgundy just come into its prime. No one had made any further remarks about coats or imperial relations, and after several courses, Laurence had thawed enough to apply himself with a will to a charming trifle assembled out of Naples biscuits and sponge-cake, with a rich brandied custard flavoured with orange, when a commotion outside the dining room began to intrude, and finally a single piercing shriek, like a woman’s cry, interrupted the increasingly loud and slurred conversation.

Silence fell, glasses stopped in mid-air, some chairs were pushed back; Staunton rose, a little wavering, and begged their pardon. Before he could go to investigate, the door was thrust abruptly open, Staunton’s anxious servant stumbling back into the room still protesting volubly in Chinese. He was gently but with complete firmness being pressed aside by another Oriental man, dressed in a padded jacket and a round, domed hat rising above a thick roll of dark wool; the stranger’s clothing was dusty and stained yellow in places, and not much like the usual native dress, and on his gauntleted hand perched an angry-looking eagle, brown and golden feathers ruffled up and a yellow eye glaring; it clacked its beak and shifted its perch uneasily, great talons puncturing the heavy block of padding.

When they had stared at him and he at them in turn, the stranger further astonished the room by saying, in pure drawing-room accents, ‘I beg your pardon, gentlemen, for interrupting your dinner; my errand cannot wait. Is Captain William Laurence here?’

Laurence was at first too bemused with wine and surprise to react; then he rose and stepped away from the table, to accept a sealed oilskin packet under the eagle’s unfriendly stare. ‘I thank you, sir,’ he said. At a second glance, the lean and angular face was not entirely Chinese: the eyes, though dark and faintly slanting, were rather more Western in shape, and the colour of his skin, much like polished teak wood, owed less to nature than to the sun.

The stranger inclined his head politely. ‘I am glad to have been of service.’ He did not smile, but there was a glint in his eye suggestive of amusement at the reaction of the room, which he was surely accustomed to provoking; he threw the company all a final glance, gave Staunton a small bow, and left as abruptly as he had come, going directly past a couple more of the servants who had come hurrying to the room in response to the noise.

‘Pray go and give Mr. Tharkay some refreshment,’ Staunton said to the servants in an undertone and sent them after him; meanwhile Laurence turned to his packet. The wax had been softened by the summer heat, the impression mostly lost, and the seal would not easily come away or break, pulling like soft candy and trailing sticky threads over his fingers. A single sheet within only, written from Dover in Admiral Lenton’s own hand, and in the abrupt style of formal orders: a single look was enough to take it in

… and you are hereby required without the loss of a Moment to proceed to Istanbul, there to receive by the Offices of Avraam Maden, in the service of H. M. Selim III, three Eggs now through agreement the Property of His Majesty’s Corps, to be secured against the Elements with all due care for their brooding and thence delivered straightaway to the charge of those Officers appointed to them, who shall await you at the covert at Dunbar …

The usual grim epilogues followed, herein neither you nor any of you shall fail, or answer the contrary at your peril; Laurence handed the letter to Granby, then nodded to him to pass the letter to Riley and to Staunton, who had joined them in the privacy of the library.

‘Laurence,’ Granby said, after handing it on, ‘we cannot sit here waiting for repairs with a months-long sea journey after that; we must get going at once.’

‘Well, how else do you mean to go?’ Riley said, looking up from the letter, which he was reading over Staunton’s shoulder. ‘There’s not another ship in port that could hold Temeraire’s weight for even a few hours; you can’t fly straight across the ocean without a place to rest.’

‘It’s not as though we were going to Nova Scotia, and could only go by sea,’ Granby said. ‘We must take the overland route instead.’

‘Oh, come now,’ Riley said impatiently.

‘Well, and why not?’ Granby demanded. ‘Even aside from the repairs, it’s going by sea that is out of the way, we lose ages having to circle around India. Instead we can make a straight shot across Tartary—’

‘Yes, and you can jump in the water and try to swim all the way to England, too,’ Riley said. ‘Sooner is better than late, but late is better than never; the Allegiance will get you home quicker than that.’

Laurence listened to their conversation with half an ear, reading the letter again with fresh attention. It was difficult to separate the true degree of urgency from the general tenor of a set of orders; but though dragon eggs might take a long time indeed to hatch, they were unpredictable and could not be left sitting indefinitely. ‘And we must consider, Tom,’ he said to Riley, ‘that it might easily be as much as five months’ sailing to Basra if we are unlucky in the way of weather, and from there we should have a flight overland to Istanbul in any case.’

‘And as likely to find three dragonets as three eggs at the end of it, no use at all,’ Granby said; when Laurence asked him, he gave as his firm opinion that the eggs could not be far from hatching; or at least not so far as to set their minds at ease. ‘There aren’t many breeds who go for longer than a couple of years in the shell,’ he explained, ‘and the Admiralty won’t have bought eggs less than halfway through their brooding: any younger than that, and you cannot be sure they will come off. We cannot lose the time; why they are sending us to get them instead of a crew from Gibraltar I don’t in the least understand.’

Laurence, less familiar with the various duty stations of the Corps, had not yet considered this possibility, and now it struck him also as odd that the task had been delegated to them, being so much further distant. ‘How long ought it take them to get to Istanbul from there?’ he asked, disquieted; even if much of the coast along the way were under French control, patrols could not be everywhere, and a single dragon flying should have been able to find places to rest.

‘Two weeks, perhaps a little less flying hard all the way,’ Granby said. ‘While I don’t suppose we can make it in less than a couple of months, ourselves, even going overland.’

Staunton, who had been listening anxiously to their deliberations, now interjected, ‘Then must not these orders by their very presence imply a certain lack of urgency? I dare say it has taken three months for the letter to come this far. A few months more, then, can hardly make a difference; otherwise the Corps would have sent someone nearer.’

‘If anyone nearer could be sent,’ Laurence said, grimly. England was hard-up enough for dragons that even one or two could not easily be spared in any sort of a crisis, certainly not for a month going and coming back, and certainly not a heavy-weight in Temeraire’s class. Bonaparte might once again be threatening invasion across the Channel, or launching attacks against the Mediterranean Fleet, leaving only Temeraire, and the handful of dragons stationed in Bombay and Madras, at any sort of liberty.

‘No,’ Laurence concluded, having contemplated these unpleasant possibilities, ‘I do not think we can make any such assumption, and in any case there are not two ways to read without the loss of a moment, not when Temeraire is certainly able to go. I know what I would think of a captain with such orders who lingered in port when tide and wind were with him.’

Seeing him thus beginning to lean towards a decision, Staunton at once began, ‘Captain, I beg you will not seriously consider taking so great a risk,’ while Riley, more blunt with nine years’ acquaintance behind him, said, ‘For God’s sake, Laurence, you cannot mean to do any such crazy thing.’

He added, ‘And I do not call it lingering in port, to wait for the Allegiance to be ready; if you like, taking the overland route should rather be like setting off headlong into a gale, when a week in port will bring clear skies.’

‘You make it sound as though we might as well slit our own throats as go,’ Granby exclaimed. ‘I don’t deny it would be awkward and dangerous with a caravan, lugging goods all across Creation, but with Temeraire, no one will give us any trouble, and we only need a place to drop for the night.’

‘And enough food for a dragon the size of a first-rate,’ Riley fired back.

Staunton, nodding, seized on this avenue at once. ‘I think you cannot understand the extreme desolation of the regions you would cross, nor their vastness.’ He hunted through his books and papers to find Laurence several maps of the region: an inhospitable place even on parchment, with only a few lonely small towns breaking up the stretches of nameless wasteland, great expanses of desert entrenched behind mountains, and on one dusty and crumbling chart a spidery old-fashioned hand had written heere ys no water 3 wekes in the empty yellow bowl of the desert. ‘Forgive me for speaking so strongly, but it is a reckless course, and I am convinced not one which the Admiralty can have meant you to follow.’

‘And I am convinced Lenton should never have conceived of our whistling six months down the wind,’ Granby said. ‘People do come and go overland; what about that fellow Marco Polo, and that nearly two centuries ago?’

‘Yes, and what about the Fitch and Newbery expedition, after him,’ Riley said. ‘Three dragons all lost in the mountains, in a five-day blizzard, through just such reckless behaviour—’

‘This man Tharkay, who brought the letter,’ Laurence said to Staunton, interrupting an exchange which bade fair to end in hot words, Riley’s tone growing rather sharp and Granby’s pale skin flushing up with tell-tale colour. ‘He came overland, did he not?’

‘I hope you do not mean to take him for your model,’ Staunton said. ‘One man can go where a group cannot, and manage on very little, particularly a rough adventurer such as he. More to the point, he risks only himself when he goes: you must consider that in your charge is an inexpressibly valuable dragon, whose loss must be of greater importance than even this mission.’

‘Oh, pray let us be gone at once,’ said the inexpressibly valuable dragon, when Laurence had carried the question, still unresolved, back to him. ‘It sounds very exciting to me.’ Temeraire was wide awake now in the relative cool of the evening, and his tail was twitching back and forth with enthusiasm, producing moderate walls of sand to either side upon the beach, not much above the height of a man. ‘What kind of dragons will the eggs be? Will they breathe fire?’

‘Lord, if they would only give us a Kazilik,’ Granby said. ‘But I expect it will be ordinary middle-weights: these kinds of bargains are made to bring a little fresh blood into the lines.’

‘How much more quickly would we be at home?’ Temeraire asked, cocking his head sideways so he could focus one eye upon the maps, which Laurence had laid out over the sand. ‘Why, only see how far out of our way the sailing takes us, Laurence, and it is not as though I must have wind always, as the ship does: we will be home again before the end of summer,’ an estimate as optimistic as it was unlikely, Temeraire not being able to judge the scale of the map so very well; but at least they would likely be in England again by late September, and that was an incentive almost powerful enough to overrule all caution.

‘And yet I cannot get past it,’ Laurence said. ‘We were assigned to the Allegiance, and Lenton must have assumed we would come home by her. To go haring off along the old silk roads has an impetuous flavour; and you need not try and tell me,’ he added repressively to Temeraire, ‘that there is nothing to worry about.’

‘But it cannot be so very dangerous,’ Temeraire said, undaunted. ‘It is not as though I were going to let you go off all alone, and get hurt.’

‘That you should face down an army to protect us I have no doubt,’ Laurence said, ‘but a gale in the mountains even you cannot defeat.’ Riley’s reminder of the ill-fated expedition lost in the Karakorum Pass had resonated unpleasantly. Laurence could envision all too clearly the consequences should they run into a deadly storm: Temeraire borne down by the frozen wind, wet snow and ice forming crusts upon the edges of his wings, beyond where any man of the crew could reach to break them loose; the whirling snow blinding them to the hazards of the cliff walls around them and turning them in circles; the dropping chill rendering him by insensible degrees heavier and more sluggish, and worse prey to the ice, with no shelter to be found. In such circumstances, Laurence would be forced to choose between ordering him to land, condemning him to a quicker death in hopes of sparing the lives of his men, or letting them all continue on the slow grinding road to destruction together: a horror beside which Laurence could contemplate death in battle with perfect equanimity.

‘So then the sooner we go the better, for having an easy crossing of it,’ Granby argued. ‘August will be better than October for avoiding blizzards.’

‘And for being roasted alive in the desert instead,’ Riley said.

Granby rounded on him. ‘I don’t mean to say,’ he said, with a smoldering look in his eye that belied his words, ‘that there is anything old-womanish in all these objections—’

‘For there is not, indeed,’ Laurence broke in sharply. ‘You are quite right, Tom; the danger is not a question of blizzards in particular, but that we have not the first understanding of the difficulties particular to the journey. And that we must remedy, first, before we engage either to go or to wait.’

‘If you offer the fellow money to guide you, of course he will say the road is safe,’ Riley said. ‘And then just as likely leave you halfway to nowhere, with no recourse.’

Staunton also tried again to dissuade Laurence, when he came seeking Tharkay’s direction the next morning. ‘He occasionally brings us letters, and sometimes will do errands for the Company in India,’ Staunton said. ‘His father was a gentleman, I believe a senior officer, and took some pains with his education; but still the man cannot be called reliable, for all the polish of his manners. His mother was a native woman, Thibetan or Nepalese, or something like; and he has spent the better part of his life in the wild places of the earth.’

‘For my part, I should rather have a guide half-British than one who can scarcely make himself understood,’ Granby said afterwards, as he and Laurence together picked their way along the back streets of Macau; the late rains were still puddled in the gutters, a thin slick of green overlaid on the stagnating waste. ‘And if Tharkay were not so much a gypsy he wouldn’t be of any use to us; it is no good complaining about that.’

At length they found Tharkay’s temporary quarters: a wretched little two-story house in the Chinese quarter with a drooping roof, held up mostly by its neighbours to either side, all of them leaning against one another like drunken old men, with a landlord who scowled before leading them within, muttering.

Tharkay was sitting in the central court of the house, feeding the eagle gobbets of raw flesh from a dish; the fingers of his left hand were marked with white scars where the savage beak had cut him on previous feedings, and a few small scratches bled freely now, unheeded. ‘Yes, I came overland,’ he said, to Laurence’s inquiry, ‘but I would not recommend you the same road, Captain; it is not a comfortable journey, when compared against sea travel.’ He did not interrupt his task, but held up another strip of meat for the eagle, which snatched it out of his fingers, glaring at them furiously with the dangling bloody ends hanging from its beak as it swallowed.

It was difficult to know how to address him: neither a superior servant, nor a gentleman, nor a native, all his refinements of speech curiously placed against the scruff and tumble of his clothing and his disreputable surroundings; though perhaps he could have gotten no better accommodations, curious as his appearance was, and with the hostile eagle as his companion. He made no concessions, either, to his odd, in-between station; a certain degree of presumption almost in his manner, less formal than Laurence would himself have used to so new an acquaintance, almost in active defiance against being held at a servant’s distance.

But Tharkay answered their many questions readily enough, and having fed his eagle and set it aside, hooded, to sleep, he even opened up the kit which had carried him there so that they might inspect the vital equipment: a special sort of desert tent, fur-lined and with leather-reinforced holes spaced evenly along the edges, which he explained could be lashed quickly together with similar tents to form a single larger sheet to shield a camel, or in larger numbers a dragon, against sandstorm or hail or snow. There was also a snug leather-wrapped canteen, well-waxed to keep the water in, and a small tin cup tied on with string, marks engraved into it halfway and near the rim; a neat small compass, in a wooden case, and a thick journal full of little hand-sketched maps, and directions taken down in a small, neat hand.

All of it showed signs of use and good upkeep; plainly he knew what he was about, and he did not show himself overeager, as Riley had feared, for their custom. ‘I had not thought of returning to Istanbul,’ Tharkay said instead, when Laurence at last came around to inquiring if he would be their guide. ‘I have no real business there.’

‘But have you any elsewhere?’ Granby said. ‘We will have the devil of a time getting there without you, and you should be doing your country a service.’

‘And you will be handsomely paid for your trouble,’ Laurence added.

‘Ah, well, in that case,’ Tharkay said, a wry twist to his smile.

‘Well, I only wish you may all not have your throats slit by Uygurs,’ Riley said in deep pessimism, giving up, after he had tried once more at dinner to persuade them to remain. ‘You will dine with me on board tomorrow, Laurence?’ he asked, stepping into his barge. ‘Very good. I will send over the raw leather, and the ship’s forge,’ he called, his voice drifting back over the sound of the oars dipping into the water.

‘I will not let anyone slit your throats at all,’ Temeraire said, a little indignantly. ‘Although I would like to see an Uygur; is that a kind of dragon?’

‘A kind of bird, I think,’ Granby said; Laurence was doubtful, but he did not like to contradict when he was not sure himself.

‘Tribesmen,’ Tharkay said, the next morning.

‘Oh.’ Temeraire was a little disappointed; he had seen people before. ‘That is not very exciting, but perhaps they are very fierce?’ he asked hopefully.

‘Have you enough money to buy thirty camels?’ Tharkay asked Laurence, after he had finally escaped a lengthy interrogation as to the many other prospective delights of their journey, such as violent sandstorms and frozen mountain passes.

‘We are going by air,’ Laurence said, confused. ‘Temeraire will carry us,’ he added, wondering if Tharkay had perhaps misunderstood.

‘As far as Dunhuang,’ Tharkay said equably. ‘Then we will need to buy camels. A single camel can carry enough water for a day, for a dragon of his size; and then of course he can eat the camel.’

‘Are such measures truly necessary?’ Laurence said, in dismay at losing so much time: he had counted on crossing the desert quickly, on the wing. ‘Temeraire can cover better than a hundred miles in a day at need; surely we can find water over such an expanse.’

‘Not in the Taklamakan,’ Tharkay said. ‘The caravan routes are dying, and the cities die with them; the oases have mostly failed. We ought to be able to find enough for us and the camels, but even that will be brackish. Unless you are prepared to risk his dying of thirst, we carry our own water.’

This naturally putting a period to any further debate, Laurence was forced to apply to Sir Thomas for some assistance in the matter, having had no expectation, on his departure from England, that his ready funds should need to stretch to accommodate thirty camels and supplies for an overland journey. ‘Nonsense, it is a trifle,’ Staunton said, refusing his offered note of hand. ‘I dare say I will have cleared fifty thousand pounds in consequence of your mission, when all is said and done. I only wish I did not think I was speeding you on the way to your destruction. Laurence, forgive me for making so unpleasant a suggestion; I would not like to plant false suspicions in your head, but the possibility has been preying on me since you decided upon going. Could the letter by any chance have been forged?’

Laurence looked at him in surprise, and Staunton went on, ‘Recall that the orders, if honest, must have been written before news of your success here in China reached England— if indeed that news has reached them yet. Only consider the effect upon the negotiations so lately completed if you and Temeraire had unceremoniously gone away in the midst of them: you would have had to sneak out of the country like thieves to begin with, and an insult of such magnitude would surely have meant war. I am hard-pressed to imagine any reason the Ministry should have sent such orders.’

Laurence sent for the letter and for Granby; together they studied it fresh in the strong sunlight from the east-facing windows. ‘I am damned if I am any judge of such things, but it seems Lenton’s hand to me,’ Granby said doubtfully, handing it back.

To Laurence also; the letters were slant and wavering, but this kind of affliction, he did not say to Staunton, was not uncommon; aviators were taken into service at the age of seven, and the most promising among them often became runners by ten, with studies neglected sadly in favour of practical training: his own young cadets were inclined to grumble at his insistence that they should learn to write a graceful hand and practice their trigonometry.

‘Who would bother with it, any road?’ Granby said. ‘That French ambassador hanging about Peking, De Guignes— he left even before we did, and by now I expect he is halfway to France. Besides, he knows well enough that the negotiations are over.’

‘There might be French agents less well-informed behind it,’ Staunton said, ‘or worse, with knowledge of your recent success, trying to lure you into a trap. Brigands in the desert would hardly be above taking a bribe to attack you, and there is something too convenient in the arrival of this message, just when the Allegiance has been damaged, and you are sure to be chafing at your enforced delay.’

‘Well, I make no secret I had as lief go myself, for all this nay-saying and gloom,’ Granby said, as they walked back to their residence: the crew had already begun the mad scramble of preparation, and haphazard bundles were beginning to be piled upon the beach. ‘So it may be dangerous; we are not nursemaids to a colicky baby, after all. Dragons are made to fly, and another nine months of this sitting about on deck and on shore will be the ruin of his fighting-edge.’

‘And of half the boys, if they have not been spoilt already,’ Laurence said grimly, observing the antics of the younger officers, who were not entirely reconciled to being so abruptly put back to work, and engaging in more boisterous behaviour than he liked to see from men on duty.

‘Allen,’ Granby called sharply, ‘mind your damned harness-straps, unless you want to be started with them.’ The hapless young ensign had not properly buckled on his flying-harness, and the long carabiner straps were dragging on the ground behind him, bidding fair to trip him and any other crewman who crossed his path.

The ground-crew master Fellowes and his harness-men were still labouring over the flying rig, not yet repaired after the fire: a good many straps stiff and hard with salt, or rotted or burnt through, which needed replacing; too, several buckles had twisted and curled from the heat, and the armourer Pratt panted over his makeshift forge on shore as he pounded them straight and flat once more.

‘A moment, and I will see,’ Temeraire said, when they had put it on him to try, and leapt aloft in a stinging cloud of sand. He flew a small circuit and landed, directing the crew, ‘Pray tighten the left shoulder-strap a little, and lengthen the crupper,’ but after some dozen small adjustments he pronounced himself satisfied with the whole.

They laid it aside while he had his dinner: an enormous horned cow spit-roasted and dressed with heaps of green and scarlet peppers with blackened skins, and also a great mound of mushrooms, which he had acquired a taste for in Capetown; meanwhile Laurence sent his men to dinner and rowed over to the Allegiance to have a final meal with Riley, convivial though quiet; they did not drink very much, and afterwards Laurence gave him a last few letters for his mother and for Jane Roland, the official post having already been exchanged.

‘Godspeed,’ Riley said, seeing him down the side; the sun was low and nearly hidden behind the buildings of the town as Laurence was rowed back to shore. Temeraire had nibbled the last of the bones clean, and the men were coming out of the house. ‘All lies well,’ Temeraire said, when they had rigged him out once more, and then the crew climbed aboard, latching their individual harnesses onto Temeraire’s with their locking carabiners.

Tharkay, his hat buttoned on with a strap under the chin, climbed easily up and tucked himself away near Laurence, close to the base of Temeraire’s neck; the eagle, hooded, was in a small cage strapped against his chest. Abruptly from the Allegiance came the sudden thunder of cannon-fire: a formal salute, and Temeraire roared out gladly in answer while the flag-signal broke out from the mainmast: fair wind. With a quick bunching of muscle and sinew, a deep hollow rushing intake of breath beneath the skin, all the chambers of air swelling out wide, Temeraire was aloft, and the port and the city went rolling away beneath him.

Chapter Two (#ulink_e461bfa9-53c6-59c2-a6e8-e1283f98f6ca)

They went quickly, very quickly; Temeraire delighting in the chance to stretch his wings for once with no slower companions to hold him back. Though Laurence was at first a little cautious, Temeraire showed no sign of overexertion, no heat in the muscles of his shoulders, and after the first few days Laurence let him choose the pace as he wished. Baffled and curious officials came hurrying out to meet them whenever they came down for some food near a town of sufficient size, and Laurence was forced on more than one occasion to put on the heavy golden dragon-robes, the Emperor’s gift, to make their questions and demands for paperwork subside into a great deal of formal bowing and scraping: though at least he did not need to feel improperly dressed, as in his makeshift green coat. Where possible they began to avoid settlements, instead buying Temeraire’s meals directly from the herdsmen out in the fields, and sleeping nightly in isolated temples, wayside pavilions, and once an abandoned military outpost with the roof long fallen in but the walls still half-standing: they stretched a canopy made of their lashed-together tents over the remnants, and built their fire with the old shattered beams for tinder.

‘North, along the Wudang range, to Luoyang,’ Tharkay said. He had proven a quiet and uncommunicative companion, directing their course most often with a silent pointing finger, tapping on the compass mounted upon Temeraire’s harness, and leaving it to Laurence to pass the directions on to Temeraire. But that night he sketched at Laurence’s request a path in the dirt as they sat outside by the fire, while Temeraire peered down interestedly ‘And then we turn west, towards the old capital, towards Xian.’ The foreign names meant nothing to Laurence, every city spelled seven different ways on his seven different maps, which Tharkay had eyed sidelong and disdained to consult. But Laurence could follow their progress by the sun and the stars, rising daily in their changed places as Temeraire’s flight ate up the miles.

Towns and villages one after another, the children running along the ground underneath Temeraire’s racing shadow, waving and calling in high indistinct voices until they fell behind; rivers snaking below them and the old sullen mountains rising on their left, stained green with moss and girt with reluctant clouds unable to break free from the peaks. Dragons passing by avoided them, respectfully descending to lower ranks of the air to give way to Temeraire, except once one of the greyhound-sleek Jade Dragons, the imperial couriers who flew at heights too cold and thin for other breeds, dived down with a cheerful greeting, flitting around Temeraire’s head like a hummingbird, and as quickly darted up and away again.

As they continued north, the nights ceased to be so stiflingly hot and became instead pleasantly warm and domestic; hunting plentiful and easy even when they did not come across one of the vast nomadic herds, and good forage for the rest of them. With less than a day’s flight left to Xian, they broke their travelling early and encamped by a small lake: three handsome deer were set to roasting for their dinner and Temeraire’s, the men meanwhile nibbling on biscuit and some fresh fruit brought them by a local farmer. Granby sat Roland and Dyer down to practice their penmanship by the firelight while Laurence attempted to make out their attempts at trigonometry. These, having been carried out mid-air and with the slates subject to all the force of the wind, posed quite a serious challenge, but he was glad to see at least their calculations no longer produced hypotenuses shorter than the other sides of their triangles.

Temeraire, relieved of his harness, plunged at once into the lake: mountain streams rolled down to feed it from all sides, and its floor was lined with smooth tumbled stones; it was a little shallow now on the cusp of August, but he managed to throw water over his back, and he frolicked and squirmed over the pebbles with great enthusiasm. ‘That is very refreshing; but surely it must be time to eat now?’ he said as he climbed out, and looked meaningfully at the roasting deer; but the cooks waved their enormous spit-hooks at him threateningly, not yet satisfied with their work.

He sighed a little and shook out his wings, spattering them all with a brief shower that made the fire hiss, and settled himself down upon the shore next to Laurence. ‘I am very glad we did not wait and go by sea; how lovely it is to fly straight, as quickly as one likes, for miles and miles,’ he said, yawning.

Laurence looked down; certainly there was no such flying in England: a week such as the last would have seen them from one end of the isles to the other and back. ‘Did you have a pleasant bathe?’ he asked, changing the subject.

‘Oh, yes; those rocks were very nice,’ Temeraire said, wistfully, ‘although it was not quite as agreeable as being with Mei.’

Lung Qin Mei, a charming Imperial dragon, had been Temeraire’s intimate companion in Peking; Laurence had feared since their departure that Temeraire might privately be pining for her. But this sudden mention seemed a non sequitur, nor did Temeraire seem very love-lorn in his tone. Then Granby said, ‘Oh, dear,’ and stood up to call across the camp, ‘Mr. Ferris! Mr. Ferris, tell those boys to pour out that water, and go and fetch some from the stream instead, if you please.’

‘Temeraire!’ Laurence said, scarlet with comprehension.

‘Yes?’ Temeraire looked at him, puzzled. ‘Well, do you not find it more pleasant to be with Jane, than to—’

Laurence stood up hastily, saying, ‘Mr. Granby, pray call the men to dinner now,’ and pretended not to hear the unsteady stifled mirth in Granby’s voice as he said, ‘Yes, sir,’ and dashed away.

Xian was an ancient city, the former capital of the nation and full of the memory of glory, the thin scattering of carts and travellers lonely on the wide and weed-choked roads leading in to the city; they flew over high moated walls of grey brick, pagoda towers standing dark and empty, only a few guards in their uniforms and a couple of lazy scarlet dragons yawning. From above, the streets quartered the city into chessboard squares, marked with temples of a dozen descriptions, incongruous minarets cheek by jowl with the sharp-pointed pagoda roofs. Narrow poplars and old, old pines with fragile wisps of green needles lined the avenues, and they were received in a marble square before the main pagoda by the magistrate of the city, officials assembled and bowing in their robes: news of their approach was outrunning them, likely on the wings of the Jade Dragon courier. They were feasted on the banks of the Wei river in an old pavilion overlooking rustling wheat fields, on hot milky soup and skewers of mutton, three sheep roasted together on a spit for Temeraire, and the magistrate ceremonially broke sprigs of willow in farewell as they left: wishes for a safe return.

Two days later they slept near Tianshui in caves hollowed from red rock, full of silent unsmiling Buddhas, hands and faces reaching out from the walls, garments draped in eternal folds of stone, and rain falling outside beyond the grotto openings. Monumental figures peered after them through the continuing mist as they flew onward, tracking the river or its tributaries now into the heart of the mountain range, narrow winding passes not much wider than Temeraire’s wingspan. He delighted in flying through these at great speed, stretching himself to the limit, his wing-tips nearly brushing at the awkward saplings that jutted out sideways from the slopes, until one morning a freakish start of wind came suddenly whistling through the narrow pass, catching Temeraire’s wings on the upswing, and nearly flung him against the rock face.

He squawked ungracefully, and managed with a desperate snaking twist to turn round in mid-air and catch himself on his legs against the nearly vertical slope. The loose shale and rock at once gave way, the little scrubby growth of green saplings and grass inadequate to stabilize the ground beneath his weight; ‘Get your wings in!’ Granby yelled, through his speaking-trumpet: Temeraire by instinct was trying to beat away into the air again, and only hastening the collapse. Pulling his wings tight, he managed a clawing and flailing scramble down the loose slope, and landed awkwardly athwart the stream bed, his sides heaving.

‘Order the men to make camp,’ Laurence said quickly to Granby, unhooking his carabiner rings, and scrambled down in a series of half-controlled drops, barely grasping the harness with his fingers before letting himself down another twenty feet, hurrying to Temeraire’s head. He was drooping, the tendrils and ruff all quivering with his too-quick panting, and his legs were trembling, but he held himself up while the poor bell-men and the ground crew let themselves off staggering, all of them half-choking and caked with the grey dirt thrown up in the frantic descent.

Though they had scarcely gone an hour, everyone was glad to stop and rest, the men throwing themselves down upon the dusty yellow grass-banks even as Temeraire himself did. ‘You are sure it does not pain you anywhere?’ Laurence asked anxiously, while Keynes clambered muttering over Temeraire’s shoulders, inspecting the wing-joints.

‘No, I am well,’ Temeraire said, looking more embarrassed than injured, though he was glad to bathe his feet in the stream, and hold them out to be scrubbed clean, some of the dirt and pebbles having crept under the hard ridge of skin around the talons. Afterwards he closed his eyes and put his head down for a nap, and showed no inclination to go anywhere at all; ‘I ate well yesterday; I am not very hungry,’ he answered, when Laurence suggested they might go hunting, saying he preferred to sleep. But a few hours later Tharkay reappeared – if it could be called reappearing, when his initial absence had gone quite unnoticed – and offered him a dozen fat rabbits which he had taken with the eagle. Ordinarily they would hardly have made a few bites for him, but the Chinese cooks stretched them out by stewing them with salt pork fat, turnips, and some fresh greens, and Temeraire made a sufficiently enthusiastic meal out of them, bones and all, to give the lie to his supposed lack of hunger.

He was a little shy even the next morning, rearing up on his haunches and tasting the air with his tongue as high up as he could stretch his head, trying to get a sense of the wind. Then there was a little something wrong with the harness, somehow not easy for him to describe, which required several lengthy adjustments; then he was thirsty, and the water had become overnight too muddy to drink, so they had to pile up stones for a makeshift dam to form a deeper pool. Laurence began to wonder if perhaps he had done badly not to insist they go aloft again directly after the accident; but abruptly Temeraire said, ‘Very well, let us go,’ and launched himself the moment everyone was aboard.

The tension across his shoulders, quite palpable from where Laurence sat, faded after a little while in the air, but still Temeraire went with more caution now, flying slowly while they remained in the mountains. Three days passed before they met and crossed over the Yellow River, so choked with silt it seemed less a waterway than a channel of moving earth, ochre and brown, with thick clods of grass growing out onto the surface of the water from the verdant banks. They had to purchase a bundle of raw silk from a passing river barge to strain the water through before it could be drunk, and their tea had a harsh and clayey taste even so.

‘I never thought I would be so glad to see a desert, but I could kiss the sand,’ Granby said, a few days later: the river was long behind them and the mountains had abruptly yielded that afternoon to foothills and scrubby plateau. The brown desert was visible from their camp on the outskirts of Wuwei. ‘I suppose you could drop all of Europe into this country and never find it again.’

‘These maps are thoroughly wrong,’ Laurence agreed, as he noted down in his log once more the date, and his guess as to miles traversed, which according to the charts would have put them nearly in Moscow. ‘Mr. Tharkay,’ he said, as the guide joined them at the fire, ‘I hope you will accompany me tomorrow to buy the camels?’

‘We are not yet at the Taklamakan,’ Tharkay said. ‘This is the Gobi; we do not need the camels yet. We will only be skirting its edges; there will be water enough. I suppose it would be as well to buy some meat for the next few days, however,’ he added, unconscious of the dismay he was giving them.

‘One desert ought to be enough for any journey,’ Granby said. ‘At this rate we will be in Istanbul for Christmas; if then.’

Tharkay raised an eyebrow. ‘We have covered better than a thousand miles in two weeks of travelling; surely you cannot be dissatisfied with the pace.’ He ducked into the supply-tent, to look over their stores.

‘Fast enough, to be sure, but little good that does everyone waiting for us at home,’ Granby said, bitterly; he flushed a little at Laurence’s surprised look and said, ‘I am sorry to be such a bear; it is only, my mother lives in Newcastle upon Tyne, and my brothers.’

The town was nearly midway between the covert at Edinburgh and the smaller at Middlesbrough, and provided the best part of Britain’s supply of coal: a natural target, if Bonaparte had chosen to set up a bombardment of the coast, and one which would be difficult to defend with the Aerial Corps spread thin. Laurence nodded silently.

‘Do you have many brothers?’ Temeraire inquired, unrestrained by the etiquette which had kept Laurence from similarly indulging his own curiosity: Granby had never spoken of his family before. ‘What dragons do they serve with?’

‘They are not aviators,’ Granby said, adding a little defiantly. ‘My father was a coal-merchant; my two older brothers now are in my uncle’s business.’

‘Well, I am sure that is interesting work too,’ Temeraire said with earnest sympathy, not understanding, as Laurence at once had: with a widowed mother, and an uncle who surely had sons of his own to provide for, Granby had likely been sent to the Corps because his family could not afford to keep him. A boy of seven years might be sponsored for a small sum and thus assured of a profession, if not a wholly respectable one, while his family saved his room and board. Unlike the Navy, no influence or family connections would be required to get him such a berth: the Corps was more likely to be short of applicants.

‘I am sure they will have gun-boats stationed there,’ Laurence said, tactfully changing the subject. ‘And there has been some talk of trying Congreve’s rockets for defence against aerial bombardment.’

‘I suppose that might do to chase off the French: if we set the city on fire ourselves, no reason they would go to the trouble of attacking,’ Granby said, with an attempt at his usual good humour; but soon he excused himself, and took his small bedroll into a corner of their pavilion to sleep.

* * *

Another five days of flying saw them to the Jiayu Gate, a desolate fortress in a desolate land, built of hard yellow brick that might have been fired from the very sands that surrounded it, outer walls thrice Temeraire’s height and nearly two foot thick: the last outpost standing between the heart of China and the western regions, her more recent conquests. The guards were sullen and resentful at their posts, but even so more like real soldiers to Laurence’s eye than the happier conscripts he had seen idling through most of the outposts in the rest of the country; though they had but a scattering of badly neglected muskets, their leather-wrapped sword hilts had the hard shine of long use. They eyed Temeraire’s ruff very closely as if suspecting him of an imposture, until he put it up and snorted at one of them for going so far as to tug on the spines; then they grew a little more circumspect but still insisted on searching all the party’s packs, and they made something of a fuss over the one piece Laurence had decided to bring along instead of leaving on board the Allegiance: a red porcelain vase of extraordinary beauty which he had acquired in Peking.