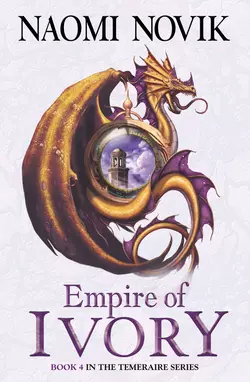

Empire of Ivory

Naomi Novik

Naomi Novik’s stunning series of novels follow the adventures of Cpt Laurence and his dragon Temeraire as they travel from the shores of Britain to China and Africa.Laurence and Temeraire made a daring journey across vast and inhospitable continents to bring home a rare Turkish dragon from the treacherous Ottoman Empire.Kazilik dragons are firebreathers, and Britain is in greater need of protection than ever, for while Laurence and Temeraire were away, an epidemic struck British shores and is killing off her greatest defence – her dragon air force is slowly dying.The dreadful truth must be kept from Napoleon at all costs. Allied with the white Chinese dragon, Lien, he would not hesitate to take advantage of Britain's weakness and launch a devastating invasion.Hope lies with the only remaining healthy dragon – Temeraire cannot stay at home, but must once again venture into the unknown to help his friends and seek out a cure in darkest Africa.

NAOMI NOVIK

Empire of Ivory

Copyright (#ud412e195-467b-578d-8273-5c5fbc121e94)

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

HarperVoyager An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd. 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd. 2007

Copyright © Naomi Novik 2007

Cover design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd. 2014

Cover illustrations © Dominic Harman

Naomi Novik asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins ebooks

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication

Source ISBN: 9780007256730

Ebook Edition © FEBRUARY 2009 ISBN: 9780007318582

Version: 2017-01-09

Dedication (#ud412e195-467b-578d-8273-5c5fbc121e94)

To Francesca,

may we always flee lions together

Contents

Title Page (#u70afc49a-68cc-5301-a2ad-84ba0fac5091)Copyright (#ud0780bb0-9e41-560e-a86d-d21625e89d37)Dedication (#u8bb156eb-ef65-5ef3-b119-4dc38ab08532)Part I (#u27d2a8c0-d30c-5770-a393-1e191b434db3)Chapter One (#u6a6341f7-6796-5df9-8d7d-935a586f0797)Chapter Two (#ud9d8375d-e03c-507e-ab4e-c9a2f7372ed9)Chapter Three (#uf6e33b20-dca6-5f23-97ac-49253a000fc7)Chapter Four (#uc3215c34-6cf3-5bfa-b487-d0484e43c4bb)Chapter Five (#litres_trial_promo)PART II (#litres_trial_promo)Chapter Six (#litres_trial_promo)Chapter Seven (#litres_trial_promo)Chapter Eight (#litres_trial_promo)Chapter Nine (#litres_trial_promo)Chapter Ten (#litres_trial_promo)Chapter Eleven (#litres_trial_promo)Chapter Twelve (#litres_trial_promo)PART III (#litres_trial_promo)Chapter Thirteen (#litres_trial_promo)Chapter Fourteen (#litres_trial_promo)Chapter Fifteen (#litres_trial_promo)Chapter Sixteen (#litres_trial_promo)Chapter Seventeen (#litres_trial_promo)Keep Reading (#litres_trial_promo)Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)By the Same Author (#litres_trial_promo) About the Publisher

PART I (#ud412e195-467b-578d-8273-5c5fbc121e94)

Chapter One (#ud412e195-467b-578d-8273-5c5fbc121e94)

‘Send up another, damn you, send them all up, at once if you have to,’ Laurence said savagely to poor Calloway, who did not deserve to be sworn at: the gunner was firing off the flares so quickly his hands were scorched black, skin cracking and peeling to bright red where some powder had spilled onto his fingers; he was not stopping to wipe them clean before setting each flare to the match.

One of the little French dragons darted in again, slashing at Temeraire’s side, and five men fell screaming as a piece of the makeshift carrying-harness unravelled. They vanished at once beyond the lantern-light and were swallowed up by the darkness; the long twisted rope of striped silk, a pillaged curtain, unfurled gently in the wind and billowed down after them, threads trailing from the torn edges. A moan went through the other Prussian soldiers still clinging desperately on to the harness, and after it low, angry mutterings in German.

Any gratitude the soldiers might have felt for their rescue from the siege of Danzig had since been exhausted: three days flying through icy rain, no food but what they had crammed into their pockets in those final desperate moments, no rest but a few hours snatched along a cold and marshy stretch of the Dutch coast, and now this French patrol harrying them all this last endless night. Men so terrified might do anything in a panic; many of them had still their small-arms and swords, and there were more than a hundred of them crammed aboard, to the less than thirty of Temeraire’s own crew.

Laurence swept the sky again with his glass, straining for a glimpse of wings, an answering signal. They were in sight of shore, the night was clear: through his glass he saw the gleam of lights dotting the small harbours all along the Scottish coast, and below heard the steadily increasing roar of the surf. Their flares ought to have been plain to see all the way to Edinburgh; yet no reinforcements had come, not a single courier-beast even to investigate.

‘Sir, that’s the last of them,’ Calloway said, coughing through the grey smoke that wreathed his head, the flare whistling high and away. The powder flash went off silently above their heads, casting the white scudding clouds into brilliant relief, reflecting from dragon scales in every direction: Temeraire all in black, the rest in gaudy colours muddied to shades of grey by the lurid blue light. The night was full of their wings: a dozen dragons turning their heads around to look back, their gleaming pupils narrowing; more coming on, all of them laden down with men, and the handful of small French patrol-dragons darting among them.

All seen in the flash of a moment, then the thunderclap crack and rumble sounded, only a little delayed, and the flare dying away drifted into blackness again. Laurence counted ten, and ten again; still there was no answer from the shore.

Emboldened, the French dragon came in once more. Temeraire aimed a swipe which would have knocked the little Pou-de-Ciel flat, but his attempt was very slow, for fear of dislodging any more of his passengers; their small enemy evaded with contemptuous ease and circled away to wait for his next chance.

‘Laurence,’ Temeraire said, looking round, ‘where is everyone? Victoriatus is in Edinburgh; he at least ought to have come. After all, we helped him, when he was hurt; not that I need help, precisely, against these little dragons,’ he added, straightening his neck with a crackle of popping joints, ‘but it is not very convenient to try and fight while we are carrying so many people.’

This was putting a braver face on the situation than it deserved: they could not very well defend themselves at all, and Temeraire was taking the worst of it, bleeding already from many small gashes along his side and flanks, which the crew could not bandage up, so cramped were they aboard.

‘Only keep everyone moving towards the shore,’ Laurence said; he had no better answer to give. ‘I cannot imagine the patrol will pursue us over land,’ he added, but doubtfully. He would never have imagined a French patrol could come so near to shore as this, either, without challenge; and how he should manage to disembark a thousand frightened and exhausted men under bombardment he did not like to contemplate.

‘I am trying; only they will keep stopping to fight,’ Temeraire said, wearily, and turned back to his work. Arkady and his rough band of mountain ferals found the small, stinging attacks maddening, and they kept trying to turn around mid-air and go after the French patrol-dragons; in their contortions they were flinging off more of the hapless Prussian soldiers than the enemy could ever have accounted for. There was no malice in their carelessness: the wild dragons were unused to men except as the jealous guardians of flocks and herds, and they did not think of their passengers as anything more than an unusual burden; but with malice or none, the men were dying all the same. Temeraire could only prevent them by constant vigilance, and now he was hovering in place over the line of flight, cajoling and hissing by turns, encouraging the others to hurry onwards.

‘No, no, Gherni,’ Temeraire called out, and dashed forward to swat at the little blue and white feral: she had dropped onto the very back of a startled French Chasseur-Vocifère: a courier beast of scarcely four tons, who could not bear up under even her slight weight and was sinking in the air despite the frantic beating of its wings. Gherni had already fixed her teeth in the French dragon’s neck and was now worrying it back and forth with savage vigour; meanwhile the Prussians clinging to her harness were all but drumming their heels on the heads of the French crew, crammed so tightly not a shot from the French side could fail of killing one of them.

In his efforts to dislodge her, Temeraire was left open, and the Pou-de-Ciel seized the fresh opportunity; this time daring enough to make an attempt at Temeraire’s back. His claws struck so near that Laurence saw the traces of Temeraire’s blood shining black on the curved edges as the French dragon lifted away again; his hand tightened on his pistol, uselessly.

‘Oh, let me, let me!’ Iskierka was straining furiously against the restraints keeping her lashed to Temeraire’s back. The infant Kazilik would soon be a force to reckon with; as yet, however, scarcely a month out of the shell, she was too young and unpracticed to be a serious danger to anyone beside herself. They had tried as best they could to secure her, with straps and chains and lecturing, but the last she roundly ignored, and though she had been but irregularly fed these last few days, she had added another five feet of length overnight: neither straps nor chains were proving of much use in restraining her.

‘Will you hold still, for all love?’ Granby said despairingly; he was throwing his own weight against the straps to try and pull her head down. Allen and Harley, the young lookouts stationed on Temeraire’s shoulders, had to go scrambling out of the way to avoid being kicked as Granby was dragged stumbling from side to side by her efforts. Laurence loosened his buckles and climbed to his feet, bracing his heels against the strong ridge of muscle at the base of Temeraire’s neck. He caught Granby by the harness-belt when Iskierka’s thrashing swung him by again, and managed to hold him steady, but all the leather was strung tight as violin-strings, trembling with the strain.

‘But I can stop him!’ she insisted, twisting her head sidelong as she tried to work free. Eager jets of flame were licking out from the sides of her jaws as she tried once again to lunge at the enemy dragon, but their Pou-de-Ciel attacker, small as he was, was still many times her size and too experienced to be frightened off by a little show of fire; he only jeered, backwinging to expose all of his speckled brown belly to her as a target in a gesture of insulting unconcern.

‘Oh!’ Iskierka coiled herself tightly with rage, the thin spiky protrusions all over her sinuous body jetting steam, and with a mighty heave reared up on her hindquarters. The straps jerked painfully out of Laurence’s grasp, and involuntarily he caught his hand back to his chest, numb fingers curling over instinctively. Granby had been dragged into mid-air and was dangling vainly from her thick neck band, while she let loose a torrent of flame: thin and yellow-white, so hot that the air about it seemed to twist and shrivel away. It made a fierce banner against the night sky.

But the French dragon had cleverly put himself before the wind, coming strong and from the east; now he folded his wings and dropped away, and the blistering flames were blown back against Temeraire’s flank. Temeraire, still scolding Gherni back into the line of flight, uttered a startled cry and jerked away while sparks scattered over the glossy blackness of his hide, perilously close to the carrying-harness of silk and linen and rope.

‘Verfluchtes Untier! Wir werden noch alle verbrennen,’ one of the Prussian officers yelled hoarsely, pointing at Iskierka, and fumbled with a shaking hand in his bandoleer for a cartridge.

‘Enough there; put up that pistol,’ Laurence roared at him through the speaking-trumpet. Lieutenant Ferris and a couple of the topmen hurriedly unlatched their harness-straps and let themselves down to wrestle it out of the officer’s hands. They could only reach the fellow by clambering over the other Prussian soldiers, however, and though too afraid to let go of the harness, the men were obstructing their passage in every other way, thrusting out elbows and hips with abrupt jerks, full of resentment and hostility.

Lieutenant Riggs was giving orders, distantly, towards the rear; ‘Fire!’ he shouted, clear over the increasing rumble among the Prussians; the handful of rifles spoke with bright powder-bursts, sulphurous and bitter. The French dragon made a little shriek and wheeled away, flying a little awkwardly: blood streaked in rivulets from a rent in its wing, where a bullet had by lucky chance struck one of the thinner patches around the joint and penetrated the hide.

The respite came a little late; some of the men were already clawing their way up towards Temeraire’s back, snatching at the greater security of the leather harness to which the aviators were hooked by their carabiner straps. But the harness could not take all their weight too, not so many of them; if the buckles stretched open, or some straps gave way, and the whole began to slide, it would entangle Temeraire’s wings and send them all plummeting into the ocean together.

Laurence loaded his pistols fresh and thrust them into his waistband, loosened his sword, and stood up again. He had willingly risked all their lives to rescue these men from a trap, and he meant to see them safely ashore if he could; but he would not see Temeraire endangered by their hysteric fear.

‘Allen, Harley,’ he said to the boys, ‘run across to the riflemen and tell Mr. Riggs: if we cannot stop them, they are to cut the carrying-harness loose, all of it; and be sure you keep latched on as you go. Perhaps you had better stay here with her, John,’ he added, when Granby made to come away with him. Iskierka was quiet for the moment, her enemy having quit the field, but she still coiled and recoiled herself in sulky restlessness, muttering in disappointment.

‘Oh, certainly! I should like to see myself do any such thing,’ Granby said, taking out his sword; he had foregone pistols since becoming Iskierka’s captain, to avoid the risk of handling open powder around her.

Laurence was too unsure of his ground to pursue an argument; Granby was not properly his subordinate any longer, and the more experienced aviator of the two of them, counting years aloft. Granby took the lead as they crossed Temeraire’s back, moving with the sureness only a boy trained up from the age of seven could have aloft; at each step Laurence handed forward his own lead-strap and let Granby lock it on to the harness for him, which he could do one-handed, that they might go more quickly.

Ferris and the topmen were still struggling with the Prussian officer in the midst of a thickening clot of men; they were disappearing from view under the violent press of bodies, only Martin’s yellow hair visible. The soldiers were near full riot, men beating and kicking at one another, thinking of nothing but an impossible escape; the knots of the carrying-harness were tightening, giving up more slack, so all the loops and bands of it hung loose and swinging with the thrashing, struggling men.

Laurence came on one of the soldiers, a young man, eyes wide and staring in his wind-reddened face and his thick moustache wet-tipped with sweat, trying to work his arm beneath the main harness, blindly, though the buckle was already straining open, and he would in a moment have slid wholly free.

‘Get back to your place!’ Laurence shouted, pointing to the nearest open loop of the carrying-harness, and thrusting the man’s hand away from the straps. Then his ears started ringing, a thick ripe smell of sour cherries flooded his nostrils as his knees folded beneath him. He put a hand to his forehead slowly, stupidly; it was wet. His own harness-straps were holding him, painfully tight against his ribs with all his weight pulling against them. The Prussian had struck him with a bottle; it had shattered, and the liquor was dripping down the side of his face.

Instinct rescued him; he put up his arm to take the next blow and pushed the broken glass back at the man’s face; the soldier said something in German and let go the bottle. They wrestled together a few moments more; then Laurence caught the man’s belt and heaved him up and away from Temeraire’s side. The soldier’s arms were spread wide, grasping at nothing; Laurence, watching, abruptly recalled himself, and at once he lunged out, reaching to his full length; but too late, and he came thumping heavily back against Temeraire’s side with empty hands; the soldier was already gone from sight.

His head did not hurt over much, but Laurence felt queerly sick and weak. Temeraire had resumed flying towards the coast, having rounded up the rest of the ferals at last, and the force of the wind was increasing. Laurence clung to the harness a moment, until the fit passed and he was able to make his hands work properly again. There were already more men clawing up: Granby was trying to hold them back, but they were overbearing him by sheer weight of numbers, even though struggling as much against one another as him. One of the soldiers grappling for a hold on the harness climbed too far out of the press; he slipped, landed heavily on the men below him, and carried them all away; as a tangled, many-limbed mass they fell into the slack loops of the carrying-harness, and the muffled wet noises of their joints and bones cracking sounded together like a roast chicken being wrenched hungrily apart.

Granby was hanging from his harness-straps, trying to get his feet planted again; Laurence crab-walked over to him and gave him a steadying arm. Below he could just make out the washy sea foam, pale against the black water; Temeraire was flying lower and lower as they neared the coast.

‘That damned Pou-de-Ciel is coming round again,’ Granby panted, as he got back his footing; the French had somehow stretched a dressing over the gash in the dragon’s wing, even if the great white patch of it was awkwardly placed and far larger than the injury made necessary. The dragon looked a little uncomfortable in the air, but he was coming on gamely nonetheless; they must have spotted Temeraire’s vulnerability. If the Pou-de-Ciel were able to catch the harness and drag it loose, it might deliberately finish what the soldiers had begun in their panic, and the chance of bringing down a heavy-weight, much less one as valuable as Temeraire, would surely tempt them to great risk.

‘We will have to cut the soldiers loose,’ Laurence said, low and wretched, and looked upwards, where the carrying-loops attached to the leather; but to send a hundred men and more to their deaths, scarce minutes from safety, he was not sure he could bear; or ever to meet General Kalkreuth again, having done it; some of the general’s own young aides were aboard Temeraire, and doing their best to keep the other men quiet.

Riggs and his riflemen were firing short, hurried volleys; the Pou-de-Ciel was keeping just out of range, waiting for the best moment to chance his attack. Then Iskierka sat up and blew out another stream of fire: Temeraire was flying ahead of the wind, so the flames were not turned against him, this time; but every man on his back had at once to throw himself flat to avoid the torrent, which burned out too quickly before it could reach the French dragon.

The Pou-de-Ciel at once darted in while the crew was distracted; Iskierka was gathering herself for another blow, and the riflemen could not get up again. ‘Christ,’ Granby said; but before he could reach her, a low rumble like fresh thunder sounded, and below them small round red mouths bloomed with smoke and powder-flashes: shore batteries, firing from the coast below. Illuminated in the yellow blaze of Iskierka’s fire, a twenty-four-pound ball of round-shot flew past them and took the Pou-de-Ciel in the chest; he folded around it like paper as it drove through his ribs, and crumpled out of the air, falling to the rocks below: they were over the shore, they were over the land, and thick-fleeced sheep were fleeing before them across the snow-matted grass.

The townspeople of the little harbour of Dunbar were alternately terrified at the descent of a whole company of dragons onto their quiet hamlet, and elated by the success of their new shore-battery, put into place scarcely two months ago and never before tried. Half-a-dozen courier-beasts driven off and one Pou-de-Ciel slain, became a Grand Chevalier and several Flammes-de-Gloire overnight, all hideously slain. The town could talk of nothing else, and the local militia strutted through the streets to general satisfaction.

The townspeople grew less enthusiastic, however, after Arkady had eaten four of their sheep; the other ferals had made only slightly less extravagant depredations, and Temeraire himself had seized upon a couple of cows, shaggy yellow-haired Highland cattle, sadly reported afterwards to be prize-winning, and devoured them to the hooves and horns.

‘They were very tasty,’ Temeraire said, apologetically; and turned his head aside to spit out some of the hair.

Laurence was not inclined to stint the dragons in the least, after their long and arduous flight, and on this occasion was perfectly willing to sacrifice his usual respect for civil property for their comfort. Some of the farmers made noises about payment, but Laurence did not mean to try and feed the bottomless appetites of the ferals out of his own pocket. The Admiralty might reach into theirs, if they had nothing better to do than sit before the fire and whistle while a battle was carrying on outside their windows, and men dying for lack of a little assistance. ‘We will not be a charge upon you for long. As soon as we hear from Edinburgh, I expect we will be called to the covert there,’ he said flatly, in reply to the protests. The horse-courier left at once.

The townspeople were more welcoming to the Prussians, most of them young soldiers pale and wretched after the flight. General Kalkreuth himself had been among these final refugees; he had to be let down from Arkady’s back in a sling, his face white and sickly under his beard. The local medical man looked doubtful, but cupped a basin full of blood, and had him carried away to the nearest farmhouse to be kept warm and dosed with brandy and hot water.

Other men were less fortunate. The harnesses, cut away, came down in filthy, tangled heaps weighted by corpses already turning green: some had been killed during the French attacks, others smothered by their own fellows in the panic, or dead of thirst, or plain terror. They buried sixty-three men out of a thousand that afternoon, some of them nameless, in a long and shallow grave laboriously pick-axed out of the frozen ground. The survivors were a ragged crew, clothes and uniforms inadequately brushed, faces still dirty, attending silently. Even the ferals, though they did not understand the language, perceived the ceremony, and sat on their haunches respectfully to watch from a distance.

Word arrived back from Edinburgh only a few hours later, but with orders so queer as to be incomprehensible. They began reasonably enough: the Prussians to be left behind in Dunbar and quartered on the town; and the dragons, as expected, were summoned to the city. But there was no invitation to General Kalkreuth or his officers to come along. On the contrary, Laurence was strictly adjured to bring no Prussian officers with him. As for the dragons, they were not permitted to enter the large and comfortable covert at all, not even Temeraire. Instead Laurence was ordered to leave them sleeping in the streets about the castle, and to report to the admiral in command in the morning.

He stifled his first reaction, and spoke mildly of the arrangements to Major Seiberling, now the senior Prussian; implying as best he could without outright falsehood that the Admiralty meant to wait until General Kalkreuth was recovered before they gave him an official welcome.

‘Oh; must we fly again?’ Temeraire said. He heaved himself wearily back onto his feet, and approached the drowsing ferals to nudge them awake: they had all crumpled into somnolence after their dinners.

Their flight to Edinburgh was slow and the days were growing short. It was only a week to Christmas, Laurence realized abruptly. The sky was fully dark by the time they reached their destination; but the castle shone out for them like a beacon, its windows and walls bright with torches as it stood on its high rocky hill above the shadowed expanse of the covert. The narrow buildings of the medieval part of the city crammed together close around it.

Temeraire hovered doubtfully above the cramped and winding streets; there were many spires and pointed roofs to contend with, and not very much room between them, giving the city the appearance of a spear-pit. ‘I do not see how I am to land here,’ he said uncertainly. ‘I am sure to break one of those buildings; why have they built these streets so small? It was much more convenient in Peking.’

‘If you cannot do it without hurting yourself, we will go away again, and orders be damned,’ Laurence said; his patience was grown very thin.

But in the end Temeraire managed to let himself down into the old cathedral square without bringing down more than a few lumps of ornamental masonry; the ferals, being all of them considerably smaller, had less difficulty. They were a little anxious at being removed from the fields full of sheep and cattle, however, and suspicious of their new surroundings; Arkady bent low and put his eye to an open window to peer inside at the empty rooms, making sceptical inquires of Temeraire as he did so.

‘That is where people sleep, is it not, Laurence? Like a pavilion,’ Temeraire said, trying cautiously to rearrange his tail into a more comfortable position. ‘And sometimes it is where they sell jewels and other pleasant things. But where are all the people?’

Laurence was quite sure that all the people had fled; the wealthiest tradesman in the city would sleep in a gutter tonight, if it were the only bed he could find in the new part of town, safely away from the pack of dragons who had invaded his streets.

The dragons eventually disposed of themselves in some manner of reasonable comfort; the ferals, used to sleeping in rough-hewn caves, were even pleased with the soft, rounded cobblestones. ‘I do not mind sleeping in the street, Laurence, truly; it is quite dry, and I am sure it will all be very interesting to look at, in the morning,’ Temeraire said, consolingly, before falling asleep with his head lodged in one alleyway and his tail in another.

But Laurence minded for him; it was not the sort of welcome which he felt they might justly have looked for, a long year away from home, having been sent halfway round the world and back. It was one thing to find themselves in rough quarters while on campaign, where no man could expect much better and might be grateful for a cow-byre to lay his head upon. But to be deposited like baggage, on cold unsanitary stones stained dark with years of street refuse, was something other; the dragons might at least have been granted use of the open farmland outside the city.

Laurence knew it was unconscious malice: the common unthinking assumption made by men who treated dragons only as inconvenient, if elevated, livestock, to be managed and herded without consideration for their own sentiments. It was an ingrained assumption. Even Laurence had recognized it as outrageous only when forced to do so by witnessing by contrast the conditions he had observed in China, where dragons were received as full members of society.

‘Well,’ Temeraire said reasonably, while Laurence laid out his own bedroll inside the house beside his head, leaving the windows open so they might continue to speak, ‘we knew how matters were here, and so we cannot be very surprised. Besides, I did not come back to make myself more comfortable, or I would have stayed in China. We must improve the circumstances of our friends. Not,’ he added, ‘that I would object to having my own pavilion; but I would rather have liberty. Dyer, pray will you retrieve that bit of gristle from between my teeth? I cannot reach far enough to put my claw upon it.’

Dyer, startled from his half-doze upon Temeraire’s back, ran to fetch the small pick from their luggage, and then scrambled obediently into Temeraire’s open jaws to scrape away.

‘You would have more luck achieving the latter if there were more men ready to grant you the former,’ Laurence said. ‘I do not mean to counsel you to despair; indeed we must not. But I had hoped to find, upon our arrival, more respect for you than when we departed, not less. It would have brought material advantage to our cause.’

Temeraire waited until Dyer had climbed out again to answer. ‘I am sure they will listen to the merits of such reform,’ he said; a large assumption, which Laurence was not at all sanguine enough to share, ‘and all the more, when I have seen Maximus and Lily and they are ranged with me. And perhaps Excidium also, for he has been in the most battles: no one could help but be impressed by him. I am sure they will see the wisdom of my arguments; they will not be as stupid as Eroica and the others were,’ Temeraire added, with obvious shades of resentment. The Prussian dragons had at first rather disdained his attempts to convince them of the merits of greater liberty and education among dragons. They were as fond of their traditional rigorous military order as their handlers, and preferred to ridicule the habits that Temeraire had acquired in China as effete.

‘I hope you will forgive me for my bluntness; but I am afraid that even if you allied the hearts and minds of every dragon in Britain with your own, it would make very little difference. As a political party you have no influence with Parliament,’ Laurence said.

‘Perhaps we do not, but I imagine if we were to go to this Parliament, we would be attended to,’ Temeraire said, an image most convincing, if not likely to produce the sort of attention Temeraire desired.

He said as much, and added, ‘We must find some better means of drawing sympathy to your cause, from those who have the influence to foster political change. I am only sorry I cannot apply to my father for advice, as relations stand between us.’

‘Well, I am not sorry, at all,’ Temeraire said, putting back his ruff. ‘I am sure he would not have helped us; and we can do perfectly well without him.’ Aside from his loyalty, which would have made him resent coldness towards Laurence on any grounds, Temeraire viewed Lord Allendale’s objections to the Aerial Corps as objections to him personally. Despite them never having met, he felt violently towards anyone whose sentiments would have seen Laurence separated from him.

‘My father has been engaged in politics for half of his life,’ Laurence said. Lord Allendale made special effort towards abolition in particular, it was a movement that had been met with as much scorn at its inception, as Laurence anticipated for Temeraire’s own cause. ‘I assure you his advice would be of the greatest value; and I do mean to effect a repair, if I can, which would allow us to consult him.’

‘I would as soon have kept it, myself,’ Temeraire muttered, meaning the elegant red vase that Laurence had purchased in China as a conciliatory gift. It had since travelled with them five thousand miles and more, and Temeraire had grown as possessive of it. He sighed when it was finally sent away, with a brief and apologetic note.

But Laurence was all too conscious of the difficulties that faced them, and of his own inadequacy to progress so vast and complicated a campaign. He had been a boy when Wilberforce had come to their house. He came as the guest of one of Lord Allendale’s political friends, newly inspired with fervour against the slave trade and just beginning the parliamentary campaign to abolish it. That was twenty years ago, and despite the most heroic efforts by men of ability, wealth and power greater than his own, a million souls or more must have been carried away from their native shores since then.

Temeraire had been hatched for only a few years; for all his intelligence, he could not yet grasp the weary struggle which was the required path to a political position, however moral and just it was, however necessary, or contrary to their immediate self-interest it was. Laurence bade him good-night without further disheartening advice; but as he closed the windows, which began to rattle gently from the sleeping dragon’s breath, the distance to the covert beyond the castle walls seemed to him less easily bridged than all the long miles which had brought them home from China.

The Edinburgh streets were quiet in the morning, unnaturally so, and deserted but for the dragons sleeping in stretched ranks over the old grey cobbles. Temeraire’s great bulk was heaped awkwardly before the smoke-stained cathedral and his tail running down into an alleyway scarcely wide enough to hold it. The sky was clear, cold and very blue, only a scattering of terraced clouds ran out to sea, a faint suggestion of pink and orange lighting the stones.

Tharkay was awake, the only soul stirring; he sat crouched against the cold in one of the narrow doorways; an elegant home, the heavy door stood open behind him. He had a cup of tea, steaming in the air. ‘May I offer you one?’ he inquired. ‘I am sure the owners would not begrudge us.’

‘No, thank you; I must go up and see about the dragons,’ Laurence said; he had been woken by a runner from the castle, summoning him to a meeting in the castle, at once. Another piece of discourtesy, when they had arrived so late; and to make matters worse, the boy had been unable to tell him if any provision had been made for the hungry dragons. What the ferals would say when they awoke, Laurence did not like to think.

‘You need not worry; I am sure they can fend for themselves,’ Tharkay said blandly, not a cheering prospect, and offered Laurence his own cup as consolation; Laurence sighed and drained it, grateful for the strong, hot brew.

He was escorted from the castle gates to the admiral’s office by a young red-coated Marine, their path winding around to the headquarters building through the medieval stone courtyards, empty and free from hurry in the early morning dimness. The doors were opened, and he went in stiffly, straight-shouldered; his face had set into disapproving lines, cold and rigid. ‘Sir,’ he said, eyes fixed at a point upon the wall; and only then glanced down, and said, surprised, ‘Admiral Lenton?’

‘Laurence. Yes, sit; sit down.’ Lenton dismissed the guard, and the door closed upon them and the musty, book-lined room; the Admiral’s desk was nearly clear, but for a single small map, a handful of papers. Lenton sat for a moment silently. ‘It is damned good to see you,’ he said at last. ‘Very good to see you indeed. Very good.’

Laurence was very much shocked at his appearance. In the year since their last meeting, Lenton seemed to have aged ten: hair gone entirely white, and a vague, rheumy look in his eyes; his jowls hung slack. ‘I hope I find you well, sir,’ Laurence said, deeply sorry, no longer wondering why Lenton had been transferred north to Edinburgh, a quieter post. He wondered what illness had ravaged him so, and who had been made commander at Dover in his place.

‘Oh…’ Lenton waved his hand, fell silent. ‘I suppose you have not been told anything,’ he said, after a moment. ‘No, that is right; we agreed we could not risk word getting out.’

‘No, sir,’ Laurence said, anger kindling afresh. ‘I have heard nothing, and been told nothing. Our allies asked me daily for word of the Corps, until they knew there was no more use in asking.’

He had given his personal assurances to the Prussian commanders. He had sworn that the Aerial Corps would not fail them; that the promised company of dragons, which might have turned the tide against Napoleon in this last disastrous campaign, would still arrive at any moment. He and Temeraire had stayed and fought in their place when the dragons did not arrive, risking their own lives and those of his crew in an increasingly hopeless cause; but the dragons had never come.

Lenton did not immediately answer, but sat nodding to himself, murmuring. ‘Yes, that is right, of course.’ He tapped a hand on the desk, looked at some papers without reading them, a portrait of distraction.

Laurence added more sharply, ‘Sir, I can hardly believe you would have lent yourself to so treacherous a course, and one so terribly short-sighted; Napoleon’s victory was by no means assured, if the twenty promised dragons had been sent.’

‘What?’ Lenton looked up. ‘Oh, Laurence, there was no question of that. No, none at all. I am sorry for the secrecy, but as for not sending the dragons, that called for no decision. There were no dragons to send.’

Victoriatus heaved his sides out and in, a gentle, measured pace. His nostrils were wide and red, a thick flaking crust edged their rims, and dried pink foam lingered about the corners of his mouth. His eyes were closed, but after every few breaths they would open a little, dull and unseeing with exhaustion; he gave a rasping, hollow cough that flecked the ground before him with blood; and subsided once again into the half-slumber that was all he could manage. His captain, Richard Clark, was lying on a cot beside him: unshaven, in filthy linen, an arm flung up to cover his eyes and the other hand resting on the dragon’s foreleg; he did not move, even when they approached.

After a few moments, Lenton touched Laurence on the arm. ‘Come, enough; let’s away.’ He turned slowly aside, leaning heavily upon a cane, and took Laurence back up the green hill to the castle. The corridors, as they returned to his offices, seemed no longer peaceful but hushed, sunk in irreparable gloom.

Laurence refused a glass of wine, too numb to think of refreshment. ‘It is a sort of consumption,’ Lenton said, looking out the windows that faced onto the covert yard; Victoriatus and twelve other great beasts lay screened from one another by the ancient windbreaks, piled branches and stones grown over with ivy.

‘How widespread?’ Laurence asked.

‘Everywhere,’ Lenton said. ‘Dover, Portsmouth, Middlesbrough. The breeding grounds in Wales and Halifax; Gibraltar; everywhere the couriers went on their rounds; everywhere.’ He turned away from the windows and took his chair again. ‘We were inexpressibly stupid; we thought it was only a cold, you see.’

‘But we had word of that before we had even rounded the Cape of Good Hope, on our journey east,’ Laurence said, appalled. ‘Has it lasted so long?’

‘In Halifax it started in September of the year five,’ Lenton said. ‘The surgeons think now it was the American dragon, that big Indian fellow: he was kept there, and then the first dragons to fall sick here were those who had shared the transport with him to Dover; then it began in Wales when he was sent to the breeding grounds there. He is perfectly hearty, not a cough or a sneeze; very nearly the only dragon left in England who is, except for a handful of hatchlings we have tucked away in Ireland.’

‘You know we have brought you another twenty,’ Laurence said, taking a brief refuge in making his report.

‘Yes, these fellows are from where, Turkestan?’ Lenton said: willing to follow. ‘Did I understand your letter correctly; they were brigands?’

‘I would rather say that they were jealous of their territory,’ Laurence said. ‘They are not very pretty, but there is no malice in them. Though what use twenty dragons can be, to cover all England—’ He stopped. ‘Lenton, surely something can be done? Must be done?’ he said.

Lenton only shook his head briefly. ‘The usual remedies did some good, at the beginning,’ he said. ‘Quieted the coughing, and so forth. They could still fly, if they did not have much appetite; and colds are usually such trifling things with them. But it lingered on so long, and after a while the possets seemed to lose their effect. Some began to grow worse—’

He stopped, and after a long moment he sighed and added with an effort, ‘Obversaria is dead.’

‘Good God!’ Laurence cried. ‘Sir, I am shocked to hear it – so deeply grieved.’ It was a dreadful loss: she had been flying with Lenton some forty years, the flag-dragon at Dover for the last ten, and though relatively young had produced four eggs already; she was perhaps the finest flyer in all England, with few to even compete with her for the title. ‘That was in, let me see, August,’ Lenton said, as if he had not heard. ‘After Inlacrimas, but before Minacitus. It takes some of them worse than others. The very young hold up best, and the old ones linger; it is the ones between who have been dying. Dying first, anyway; I suppose they will all go in the end.’

Chapter Two (#ud412e195-467b-578d-8273-5c5fbc121e94)

‘Captain,’ Keynes said, ‘I am sorry, but any gormless imbecile can bandage up a bullet-wound, and a gormless imbecile is very likely to be assigned in my place. I cannot stay with the healthiest dragon in Britain when the quarantine-coverts are full of the sick.’

‘I perfectly understand, Mr. Keynes, and you need say no more,’ Laurence said. ‘Will you not fly with us as far as Dover?’

‘No; Victoriatus will not last the week; I will wait and attend the dissection with Dr. Harrow,’ Keynes said, with brutal practicality that made Laurence flinch. ‘I hope we may learn something about the characteristics of the disease. Some of the couriers are still flying; one will carry me onwards.’

‘Well,’ Laurence said, and shook the surgeon’s hand. ‘I hope we shall see you with us again soon.’

‘I hope you will not,’ Keynes said, in his usual acerbic manner. ‘If you do, I will otherwise be lacking for patients, which from the course of this disease, will mean they are all dead.’

Laurence could hardly say his spirits were lowered; they had already been reduced so far as to make the doctors loss make little difference. But he was sorry. Dragon-surgeons were not by and large near so incompetent as the naval breed, and despite Keynes’ words Laurence did not fear his eventual successor, but to lose a good man, his courage and sense proven and his eccentricities known, was never pleasant; and Temeraire would not like it.

‘He is not hurt?’ Temeraire pressed. ‘He is not sick?’

‘No, Temeraire; but he is needed elsewhere,’ Laurence said. ‘He is a senior surgeon; I am sure you would not deny his attentions to your comrades suffering from this illness.’

‘Well, if Maximus or Lily should need him,’ Temeraire said, crabbily, and drew furrows in the ground. ‘Shall I see them again soon? I am sure they cannot be so very ill. Maximus is the biggest dragon I have ever seen, even though we have been to China; he is sure to recover quickly.’

‘No, my dear,’ Laurence said, uneasily, and broke the worst of the news. ‘The sick… none of them have recovered, and you must take the very greatest care not to go anywhere near the quarantine-grounds.’

‘But I do not understand,’ Temeraire said. ‘If they do not recover, then—’ He paused.

Laurence only looked away. Temeraire had good excuse for not understanding at once. Dragons were hardy creatures, and many breeds lived a century and more; he might have justly expected to know Maximus and Lily for longer than a man’s lifetime, if the war did not take them from him.

At last, sounding almost bewildered, Temeraire said, ‘But I have so much to tell them – I came for them, so they might learn that dragons may read and write, and have property, and do things other than fight.’

‘I will write a letter for you, which we can send to them with your greetings, and they will be happier to know you are well and safe from contagion than for your company,’ Laurence said. Temeraire did not answer; he was very still, and his head bowed deeply to his chest. ‘We will be nearby,’ Laurence went on, after a moment, ‘and you may write to them every day, if you wish; when we have finished our work.’

‘Patrolling, I suppose,’ Temeraire said, with a very unusual note of bitterness, ‘and more stupid formation-work; while they are all sick, and we can do nothing.’

Laurence looked down, into his lap, where their new orders lay amid the oilcloth packet of all his papers, and had no comfort to offer: brusque instructions for their immediate removal to Dover, where Temeraire’s expectations were likely to be answered in every particular.

He was not encouraged by their arrival at Dover. They reported their presence directly after they had landed, but Laurence was left to cool his heels in the hall outside the new admiral’s office for thirty minutes, listening to voices by no means indistinct despite the heavy oaken door. He recognized Jane Roland shouting; the voices that answered her were unfamiliar too, and Laurence rose to his feet abruptly as the door was flung open. A tall man in a naval coat came rushing out with clothing and expression both disordered, his lower cheeks mottled to a moderate glow under his sideburns; he did not pause, but threw Laurence a furious glare before he left.

‘Come in, Laurence, come in,’ Jane called, and he entered the room. She stood with the admiral, an older man dressed rather astonishingly in a black frockcoat and knee breeches with buckled shoes.

‘You have not met Dr. Wapping, I think,’ Jane said. ‘Sir, this is Captain Laurence, of Temeraire.’

‘Sir,’ Laurence said, and made his leg deep to cover his confusion and dismay. He supposed that if all the dragons were in quarantine, putting the covert in the charge of a physician was the sort of thing that would make sense to landsmen. The notion had once been advanced to him by a family friend seeking his influence on behalf of a less-fortunate relation, to put forward a surgeon – not even a naval surgeon – for the command of a hospital ship.

‘I am honoured to make your acquaintance, Captain,’ Dr. Wapping said. ‘Admiral, I will take my leave; I beg your pardon for having been the cause of so unpleasant a scene.’

‘Nonsense; those rascals at the Victualing Board are a pack of unhanged scoundrels, and I am happy to put them in their place; good day to you. Would you credit it, Laurence,’ Jane said, as Wapping closed the door behind himself, ‘the wretches are not content that the poor creatures eat scarcely enough to feed a bird, but they must send us diseased stock and scrawny too?

‘But this is not any way to welcome you home.’ She caught him by the shoulders and kissed him soundly on both cheeks. ‘You are a damned sight. Whatever has happened to your coat? Will you have a glass of wine?’ She poured for them both without waiting his answer and he took the drink it in a sort of appalled blankness. ‘I have all your letters, so I have a tolerable notion what you have been doing; you must forgive me my silence, Laurence. I found it easier to write nothing than to leave out the only matter of any importance.’

‘No. That is, yes, of course,’ he said, and sat down with her at the fire. Her coat had been thrown over the arm of her chair, and now that he looked, he could see the admiral’s fourth bar on the shoulders; and the front, which was now magnificently frogged with braid. Her face, too, was altered but not for the better: she had lost a stone of weight at least, and her dark hair, cropped short, was shot with grey.

‘Well, I am sorry to be such a ruin,’ she said ruefully, and laughed away his apologies. ‘No, we are all of us decaying, Laurence, there is no denying it. You have seen poor Lenton, I suppose. He held up like a hero for three weeks after she died, but then we found him on the floor of his bedroom in an apoplexy. For a week he could not speak without slurring his words. He came along a good ways afterwards, but he is still only a shade of himself.’

‘I am deeply sorry for it,’ Laurence said, ‘though I drink to your promotion,’ and by a Herculean effort he managed it without a stutter.

‘I thank you, dear fellow,’ she said. ‘I would be full of pride, I suppose, if matters were otherwise, and if it were not one annoyance after another. We glide along tolerably well when left to our own devices, but I must consistently deal with those doltish creatures from the Admiralty. They are told, before they come, and told again, and still they will simper at me, and coo, as if I had not been a-dragonback before they were out of dresses; and then they simply stare when I dress them down for behaving like kiss-my-hand squires.’

‘I suppose they find it a difficult adjustment,’ Laurence said, with private sympathy. ‘I wonder the Admiralty should have—’ He paused, sensing that he was treading on obscure and dangerous ground. One could not very well quarrel with the pursuit, by whatever means necessary, of reconciling Longwings – perhaps Britain’s most deadly breed – to service with the corps. The beasts would accept only female handlers, and some must be offered to them. Laurence regretted the necessity that thrust gently born women out of their rightful society and into harm’s way, but at least they were raised to it. And occasionally, they had chance perforce to act as formation-leaders, transmitting manoeuvres to their wings. But an admiralty was a far cry from flag rank, and she was in command of the largest covert in Britain, and perhaps the most critical at that.

‘They certainly did not like to give it to me, but they had precious little choice,’ Jane said. ‘Portland would not come from Gibraltar; Laetificat is not fit enough for the sea-voyage. So, it was Sanderson or I. He is making a cake of himself over the business; he goes off into corners and weeps like a woman, as though that would help anything. A veteran of nine fleet actions, if you would credit it!’ She ran her hand through her disordered crop and sighed. ‘Never mind, you are not to listen to me, Laurence, I am simply impatient; and his Animosia does poorly.’

‘And Excidium?’ Laurence ventured.

‘Excidium is a tough old bird, and he knows how to husband his strength: he has the sense to eat, even though he has no appetite. He will muddle along a good while yet. And you know, he has close on a century of service; many his age have already rid themselves of the whole business and retired to the breeding grounds.’ She smiled; it was not whole-hearted. ‘There; I have been brave. Let us move on to pleasanter things. I hear you have brought me twenty dragons, and by God do I have a use for them. Let us go and see them.’

‘She is a handful and a half,’ Granby admitted softly, as they considered the coiled serpentine length of Iskierka’s body, faint threads of steam issuing from the many needle-like spikes upon her body, ‘and I didn’t ride herd on her, sir, I am sorry.’

Iskierka had already established herself to her own satisfaction, if no one else’s, by clawing out a deep pit in the clearing next to Temeraire’s where she had been housed, and then filling it with ash acquired from the demise of some two dozen young trees, the largest she could manage at present. She had unceremoniously uprooted and burnt them inside her pit, then added a collection of boulders to the powdery grey mixture, which she fired to a moderate glow before falling asleep in her heated nest. The bonfire and its lingering smoulder were visible for some distance, even from the farmhouses nearest the covert; and after only a few hours, her arrival had produced several complaints and a great deal of alarm.

‘Oh, you have done enough keeping her harnessed out in the countryside, and without a head of cattle to your name,’ Jane said, giving the drowsing Iskierka’s side a pat. ‘They may bleat to me all they like, she’s a fire-breather and you may be sure the Navy will cheer your name when they hear we have our own at last. Well done; well done indeed, and I am happy to confirm you in your rank, Captain Granby. Should you like to do the honours, Laurence?’

Most of Laurence’s crew had already been employed in Iskierka’s clearing, beating out the stray embers which flew from her pit and threatened to ignite all the entire covert if left unchecked. Ash-dusty and tired as they all were, they had stayed, lingering consciously without the need of any announcement. They lined up on one muttered word from young Lieutenant Ferris to watch Laurence pin a second pair of gold bars upon Granby’s shoulders.

‘Gentlemen,’ Jane said, when Laurence had done, and they gave a cheek-flushed Granby three huzzahs, whole-hearted if a little subdued, and Ferris and Riggs stepped over to shake him by the hand.

‘We will see about assigning you a crew, though it is early days with her yet,’ Jane said, after the ceremony had dispersed, and they proceeded on to make her acquainted with the ferals. ‘I have no shortage of men now, more’s the pity. Feed her twice daily, see if we cannot make up for any growth she may have been shorted, and whenever she is awake I will start you on Longwing manoeuvres. I don’t know if she can scorch herself, as they can with their own acid, but we needn’t find out by trial.’

Granby nodded; he seemed not the least nonplussed at answering to her. Neither did Tharkay, who had been persuaded to stay on at least a little longer, as one of the few of them with any influence upon the ferals at all. He rather looked mostly amused, in his secretive way, once past the inquiring glance which he had first cast at Laurence: as Jane had insisted upon being taken to the new-come dragons at once, there had been no chance for Laurence to give Tharkay a private caution in advance of their meeting. He did not reveal any surprise, however, but only made her a polite bow, and performed the introductions calmly.

Arkady and his band had made no little less confusion of their own clearings than Iskierka, preferring to knock down all the trees between them and cluster together in a great heap. The chill of the December air did not trouble them, used as they were to the vastly colder regions of the Pamirs, but they spoke disapprovingly of the dampness, and on discovering the senior officer of the covert before them, at once demanded an accounting of their promised cows, from her: one apiece daily, was the offer by which they had been lured into service.

‘They make the argument that if they do not eat their share of cows upon a given day, that they are still owed the cattle, and may call the credit in at a future time,’ Tharkay explained, igniting Jane’s deep laugh.

‘Tell them they shall have as much as they can eat on any occasion, and if they are too suspicious for that to satisfy them, we shall make them a tally. Each of them may take one of the logs they have knocked over to the feeding pens, and mark it each time they take a cow,’ Jane said, more merry than offended at being met with a negotiation. ‘Pray ask, will they agree to a rate of exchange? Two hogs for a cow, or two sheep, should we bring in some variety of livestock?’

The ferals put their heads together and muttered, hissed and whistled among themselves in a cacophony made private only by the obscurity of their language. Finally Arkady turned back and professed himself willing to settle, on the proviso that the rate for goats would be three to one cow; they had some measure of contempt for the species being the animals most easily obtained in their former homeland, and they also suspected them of being scrawny.

Jane bowed to him to seal the arrangement, and he bobbed his head back. His expression was one of deeply satisfaction and rendered all the more piratical by the red splash of colour covering one of his eyes and spilling down his neck.

‘They are a gang of ruffians and make no mistake,’ Jane said, as she led them back to her offices, ‘but I have no doubt of their flying capabilities, at any rate: with that sort of wiry muscle they will fly circles around anything in their weight-class, or over it, and I am happy to stuff their bellies for them.’

‘No, sir; there’ll be no trouble,’ the steward of the headquarters said, rather quietly, promising to find rooms for Laurence and his officers. Most of the other captains and officers were encamped in the quarantine-grounds with their sick dragons, despite the cold and wet, and so the building was deserted; even more hushed and silent than it had been during the low-ebb before Trafalgar, when nearly all the formations had gone south to help bring down the French and Spanish fleets.

They all drank Granby’s health, but the party broke up early, and Laurence was not disposed to linger. A few wretched lieutenants sat at a dark table in the corner, without talking; an older captain snored, his head tipped against the side of his armchair and a bottle of brandy empty by his elbow. Laurence took his supper alone in his rooms and drank his port near the fire.

He opened the door at a faint tapping, expecting perhaps Jane, or one of his men had come with some word from Temeraire, but was startled to find Tharkay instead. ‘Pray come in,’ Laurence said, and belatedly added, ‘I hope you will forgive my state.’ The room was disordered, and he had borrowed a dressing-gown from a colleague’s neglected wardrobe. It was considerably too large around the waist, and badly crumpled.

‘I am come to say good-bye,’ Tharkay said, and, ‘No, I have nothing to complain of,’ when Laurence had made an awkward inquiry, ‘but I am not of your company. I do not care to stay as only a translator; it is a role which would soon pall.’

‘I would be happy to speak to Admiral Roland – perhaps a commission—’ Laurence said, trailing away; he did not know what might be done, or how such matters were arranged in the Corps, except to imagine them a good deal less formally prescribed than in the Army, or the Navy. Tharkay was an asset of inestimable value to them as a linguist; and Laurence would have argued gladly for any measure that might persuade him to stay.

‘I have already spoken to the Admiral,’ Tharkay said, ‘and have been given one, if not the sort you mean: I will go back to Turkestan and enlist more ferals, if any more can be persuaded into your service on similar terms.’

‘No matter how mean and scrawny they are,’ Jane said, entering the room without ceremony and stripping off her gloves, which were stained by the sour-milk odour of dragon mucus, and acrid smoke. ‘Pray don’t think me ungrateful, Laurence,’ she added, coming to warm her hands at the fire, ‘it is a miracle you should have brought us Iskierka and one egg whole, considering the way Bonaparte has been romping about the Continent, much less our amiable band of brigands with them; but I would be a good deal happier to have another twenty at such a price.’

Laurence would have been a good deal happier to have the first twenty ferals more manageable; a quality they were not more likely to gain after Tharkay’s departure. ‘I will pray for your safe return,’ Laurence said, and offered his hand in farewell. He could not object, it was hard to imagine that Tharkay’s pride might allow him to remain as a supernumerary, even if mere restlessness did not drive him on.

‘What an odd fellow you have found us, Laurence,’ Jane said, when Tharkay had gone. ‘I ought to give him his weight in gold, and would, if the Admiralty would not squawk. Twenty dragons talked out of the trees, like Merlin; or was it St. Patrick? Never mind, come to my rooms, if you please. This place has a cursed draft, and my maps are there.’

The map of Europe was laid out on her table, covered with great clots of markers, representing dragon positions from the western borders of Prussia’s former territory all the way to the footsteps of Russia. ‘From Jena to Warsaw in three weeks,’ she said, as one of her runners poured wine for them. ‘I would not have given a bad ha’penny for the news, if you had not brought it yourself, Laurence; and if we hadn’t had it from the Navy, too, I would have sent you to a physician.’

Laurence nodded. ‘And I have a great deal to tell you of Bonaparte’s aerial tactics too, they have changed entirely. Formations are of no use against him; at Jena, the Prussians were routed, wholly routed. We must begin devising counters to his new methods at once.’

But she was already shaking her head. ‘Do you know, Laurence, I have less than forty dragons fit to fly? Unless Bonaparte is a lunatic, he will not come across with less than a hundred. He shan’t need any fine tactics to do for us. For our part, there is no one to learn any new defence.’

The scope of the disaster silenced him: only forty dragons, to patrol the south coast, and give cover to the ships of the blockade.

‘What we need at present is time,’ Jane continued. ‘There are a dozen hatchlings in Ireland, preserved from contagion, and twice as many eggs due to hatch in the next six months. We bred a good many of them, early on. If our friend Bonaparte is good enough to give us a year, the rest of these new shore-batteries will be in place, the young dragons brought up, and we’ll have your ferals knocked into shape; not to mention Temeraire and our new fire-breather.’

‘Will he give us a year?’ Laurence said, low, looking at the counters. There were not many near the Channel yet; but he had seen first-hand how swiftly Napoleon’s dragon-borne army could move.

‘Not a minute, if he hears anything of our pitiable state,’ Jane said. ‘But our troubles aside, well, we hear he has made a very good friend in Warsaw, a Polish countess. They say she is a raving beauty, and he would like to marry a sister of the Tsar. We will wish him good fortune in his courting, and hope that he takes his long leisurely time about it. If he is sensible, he will want a winter night to make a crossing, and the days are already growing longer.

‘But we can be sure that if he learns how thin we are on the ground, he will come posting back quick as lightning, and damn the ladies. So our task of the moment is to keep him properly in the dark. In a year’s time we will have something to work with; but until then, for you all it must be—’

‘Oh, patrolling,’ Temeraire said, in tones of despair, when Laurence had brought their orders.

‘I am sorry, my dear,’ Laurence said, ‘very truly sorry; but if we can serve our friends at all, it will be by taking on those duties which they have had to set aside.’ Temeraire was silent and brooding. In an attempt to cheer him, Laurence added, ‘But we need not abandon your cause, not in the least. I cannot write my father, as relations between us stand; but I will write my mother, and those of my acquaintance who may have the best advice to give, on how we ought to proceed—’

‘Whatever sense is there in it,’ Temeraire said, miserably, ‘when all our friends are ill, and there is nothing to be done for them? It does not matter if one is not allowed to visit London, if one cannot even fly for an hour. And Arkady does not give a fig for liberty, anyway; all he wants are cows. We may as well patrol; or even do formations.’

This was the mood in which they went aloft, a dozen of the ferals behind them more occupied in squabbling amongst themselves than in paying any attention to the sky; Temeraire was in no way inclined to make them mind, and with Tharkay gone, the few hapless officers set upon their backs had very little hope of exerting any form of control.

These young men had been chosen for their language skills. The ferals all far too old, in draconic terms, to acquire a new tongue easily, so their officers would have to learn theirs instead. To hear them trying to whistle and cluck the awkward syllables of the Durzagh language had quickly palled as entertainment and become a nuisance to the ear. But it had also to be endured; no one aside from Temeraire knew the tongue fluently, and only a few of Laurence’s younger officers had acquired a smattering in the course of their journey to Istanbul.

Laurence had indeed lost two of his already-diminished number of officers to the cause: both Dunne, one of the riflemen, and Wickley of the bellmen had a good enough grasp of Durzagh to translate basic signals, and were not so young as to make command absurd. They had been set aboard Arkady in a highly theoretical position of authority; the natural bond which the first harnessing seemed to produce was absent of course, and Arkady was far more likely to obey his own whimsical impulse than any orders which they might give. The feral leader had already expressed his opinion that flying over the ocean was absurd, he proclaimed it a useless territory for which no reasonable dragon would have interest, and the likelihood that he would veer away at any given moment in search of better entertainment seemed to Laurence precariously high.

Jane had set them a course along the coastline, for their first excursion. There was no risk at all of action, so near to land, but at least the cliffs interested the ferals. The bustle of shipping around Portsmouth had drawn their eye, and they would gladly have investigated further if not called to order by Temeraire. They flew on past Southampton and westward along towards Weymouth, setting a leisurely pace. The ferals resorted to wild acrobatics for entertainment; swooping to heights that should have rendered them dizzy and ill, save for their habituation among the loftiest mountains on the earth. They plummeted into absurd and dangerous diving manoeuvres, skimming the sea so closely that they threw up spray from the waves. It was a sad waste of energy, but the ferals now were well-fed by comparison to their previous state, and they had a surfeit which Laurence was glad enough to see spent in so unrestrained a manner, even if the officers clinging sickly to their harnesses did not agree.

‘Perhaps we might try a little fishing,’ Temeraire suggested, turning his head around, when little Gherni abruptly cried out above them, and then the world spun and whirled as Temeraire flung himself sidelong; a Pêcheur-Rayé went flying past them, and the champagne-popping of rifle-fire spat at them from his back.

‘To stations,’ Ferris was shouting, men scrambling wildly; the bellmen were casting off a handful of bombs down on the recovering French dragon below while Temeraire veered away, climbing. Arkady and the ferals were shrilly calling to one another, wheeling excitedly; they flung themselves with eagerness on the French dragons: a light scouting party of six, as best Laurence could make out among the low-lying clouds, the Pêcheur the largest of the lot and the rest all light-weights or couriers; both outnumbered and outweighed, therefore, and reckless to be coming so close to British shores.

Reckless, or deliberately venturesome; Laurence thought grimly it could not have escaped the notice of the French that their last encounter had brought no answer from the coverts.

‘Laurence, I am going after that Pêcheur; Arkady and the others will take the rest,’ Temeraire said, curving his head around even as he dived.

The ferals were not shy by any means, and gifted skirmishers, from all their play; Laurence thought it safe to leave the smaller dragons entirely to them. ‘Pray make no sustained attack,’ he called, through the speaking-trumpet. ‘Only roust them from the shore, as quickly as you may—’ as the hollow thump-thump of bombs, exploding below, interrupted.

Their own battle was not a long one; without the hope of surprise, the Pêcheur knew himself thoroughly overmatched, Temeraire a more agile flyer and in a wholly different class so far as weight. Having risked and lost a throw of the dice, he and his captain were evidently not inclined to try their luck again; Temeraire had scarcely stooped before the Pêcheur dropped low to the water and beat away quickly over the waves, his riflemen keeping up a steady fusillade to clear his retreat.

Laurence turned his attention above, to the furious howling of the ferals’ voices: they could scarcely be seen, having lured the French high aloft, where their greater ease with the thin air could tell to their advantage. ‘Where the devil is my glass?’ he said, and took it from Allen. The ferals were making a sort of taunting game of the business, darting in at the French dragons and away, setting up a raucous caterwauling as they went, without very much actual fighting to be seen. It would have done nicely to frighten away a rival gang in the wild, Laurence supposed, particularly one so outnumbered, but he did not think the French were to be so easily diverted; indeed as he watched, the five enemy dragons, all of them little Poux-de-Ciels, drew into close formation and promptly bowled through the cloud of ferals.

The ferals, still focused on their show of bravado, scattered too late to evade the rifle-fire, and now some of their shrill cries expressed real pain. Temeraire was beating furiously, his sides belling out like sails as he heaved for the breath to get himself as high, but he could not easily gain such altitude, and would be at a disadvantage to the smaller French beasts when he did. ‘Give them a gun, quickly, and show the signal for descent,’ Laurence shouted to Turner, without much hope; but the ferals came plummeting down in a rush when Turner put out the flags, none too reluctant to position themselves around Temeraire.

Arkady was keeping up a low, indignant clamouring under his breath, nudging anxiously at his second Wringe, the worst-hit, her dark grey hide marred with streaks of darker blood. She had taken several balls to the flesh and one unlucky hit to the right wing, which had struck her on the bias and scraped a long, ugly furrow across the tender webbing and two spines; she was listing in mid-air awkwardly as she tried to favour it.

‘Send her below to shore,’ Laurence said, scarcely needing the speaking-trumpet with the dragons crowded so close that they might have been talking in a clearing and not the open sky. ‘And pray tell them again, they must keep well-clear of the guns; I am sorry they have had so hot a lesson. Let us keep together and—’ but this came too late, as the French were advancing down in arrow-head formation, and the ferals followed his first instruction too closely on and had spread themselves out across the sky.

The French also at once separated; even together they were not a match for Temeraire, who they had surely recognized, and by way of protection engaged themselves closely with the ferals. It must have been an odd experience for them; Poux-de-Ciel were generally the lightest of the French combat breeds, and now they were finding themselves the relative heavy-weights in battle against the ferals, who even where their wingspan and length matched were all of them lean and concave-bellied creatures, a sharp contrast against the deep-chested muscle of their opponents.

The ferals were now more wary, but also more savage, hot with anger at the injury to their fellow and their own smaller stinging wounds. They used their darting lunges to better effect, learning quickly how to feint in and provoke the rifle volleys, then come in again for a real attack. The smallest of them, Gherni and little motley-coloured Lester, were attacking one Pou-de-Ciel together, with the more wily Hertaz pouncing in every now and again, claws blackened with blood; the others were engaged singly, and more than holding their own, but Laurence quickly perceived the danger, even as Temeraire called, ‘Arkady! Bnezh s’li taqom—’ and broke off to say, ‘Laurence, they are not listening to me.’

‘Yes, they will be in the soup in a moment,’ Laurence agreed; the French dragons, though they seemed on the face of it to be fighting as independently as the ferals, were all manoeuvring skilfully, their backs to one another; indeed they were only allowing the ferals to herd them into formation, which should allow them to make another devastating pass. ‘Can you break them apart, when they have come together?’

‘I do not see how I will be able to do it, without hurting our friends; they are so close to one another, and some of them are so little,’ Temeraire said anxiously, tail lashing as he hovered.

‘Sir,’ Ferris said, and Laurence looked at him. ‘I beg your pardon, sir, but we are always told, as a rule, to take a bruising before a ball; it don’t hurt them long, even if they are knocked properly silly, and we are close enough to give any of them a lift to land, if it should go so badly.’

‘Very good; thank you, Mr. Ferris,’ Laurence said, putting strong approval in it; he was still very glad to see Granby matched off with Iskierka, even more so when dragons would now be in such short supply, but he felt the loss keenly, as exposing the weaknesses in his own abbreviated training as an aviator. Ferris had risen to his occasions with near-heroism, but he had been but a third lieutenant on their departure from England, scarcely a year ago, and at nineteen years of age could not be expected to put himself forward to his captain with the assurance of an experienced officer.

Temeraire put his head down and puffed up his chest with a deep breath, then flung himself down among the shrinking knot of dragons, and barrelled through with much the effect of a cat descending upon an unsuspecting flock of pigeons. Friend and foe alike went tumbling wildly; and thankfully, the ferals, used to rough play, were none of them much the worse for wear, except for being flung into higher excitement. They flew around with much disorderly shrilling for a few moments, and as they did, the French righted themselves: the formation leader waved a signal-flag, and the Poux-de-Ciel wheeled together and away, escaping.

Arkady and the ferals did not pursue, but came gleefully romping back over to Temeraire, alternating complaints at his having knocked them about, with boastful prancing over their victory and the rout of the enemy, which Arkady implied was in spite of Temeraire’s jealous interference. ‘That is not true, at all,’ Temeraire said, outraged, ‘you would have been perfectly dished without me,’ and turned his back upon them and flew towards land, his ruff stiffened up with indignation.

Wringe was sitting and licking at her scarred wing in the middle of a field. A few clumps of bloodstained white wool upon the grass, and a certain atmosphere of carnage in the air, suggested she had quietly found herself some consolation; but Laurence chose to be blind. Arkady immediately set up as a hero for her benefit, and paraded back and forth to re-enact the encounter. So far as Laurence could follow, the battle might have raged a fortnight, and engaged some hundreds of enemy beasts, all of them vanquished by Arkady’s solitary efforts. Temeraire snorted and flicked his tail in disdain, but the other ferals proved perfectly happy to applaud the revised account, though they occasionally jumped up to interject stories of their own noble exploits.

Laurence meanwhile had dismounted; his new surgeon Dorset, a rather thin and nervous young man, bespectacled and given to stammering, was going over Wringe’s injuries. ‘Will she be well enough to make the flight back to Dover?’ Laurence inquired; the scraped wing looked nasty, what he could see of it; she uneasily kept trying to fold it close and away from the inspection, though fortunately Arkady’s theatrics were keeping her distracted enough that Dorset could make some attempt at handling it.

‘No,’ Dorset said absently, with not the shade of a stammer and a quite casual authority. ‘She needs to lie quiet a day or so under a poultice; and those balls must come out of her shoulder presently, although not now. There’s a courier-ground outside Weymouth, which has been taken off the routes and will be free from infection. We must find a way to get her there.’ He let go of her wing and turned back to Laurence blinking watery eyes.

‘Very well,’ Laurence said, bemused; at the change in his demeanour more than the certainty alone. ‘Mr. Ferris, have you the maps?’

‘Yes, sir; though it is twelve miles straight flying to Weymouth covert across the water, sir, if you please,’ Ferris said, hesitating over the leather wallet of maps.

Laurence nodded and waved them away. ‘Temeraire can support her so far, I am sure.’

Her weight posed less difficulty than her unease with the proposed arrangement, and, too, Arkady’s sudden fit of jealousy, which caused him to propose himself as a substitute: quite ineligible, as Wringe outweighed him by several tons, and they should not have lifted him a yard off the ground.

‘Pray do not be so silly,’ Temeraire said, as she dubiously expressed her reservations at being ferried. ‘I am not going to drop you unless you bite me. You have only to lie quiet, and it is a very short way.’

Chapter Three (#ud412e195-467b-578d-8273-5c5fbc121e94)