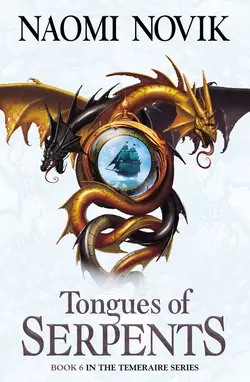

Tongues of Serpents

Tongues of Serpents

Naomi Novik

Naomi Novik’s stunning series of novels follow the global adventures of Captain William Laurence and his fighting dragon Temeraire as they are thrown together to fight for Britain during the turbulent time of the Napoleonic Wars.Laurence and Temeraire have been banished from the country they’ve fought so hard to protect - and the friends they have made in the British Aerial Corps.Found guilty of treason, man and dragon have been deported to Australia to start a new life and many new adventures.

NAOMI NOVIK

The Tongues of Serpents

Table of Contents

PART I (#ub7564d42-b9cc-57ae-b78f-07babd62f0e4)

Chapter One (#u150fbb73-bee2-515e-b733-116aee75eebb)

Chapter Two (#u365da6c9-630a-52b9-9d5c-a397b6d12af7)

Chapter Three (#ub8f69f47-9175-544b-859a-e36f11ffaf35)

Chapter Four (#ufc99b4da-d107-5113-8e99-b8586083cb50)

Chapter Five (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Six (#litres_trial_promo)

PART II (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Ten (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eleven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twelve (#litres_trial_promo)

PART III (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fourteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Sixteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seventeen (#litres_trial_promo)

Epilogue (#litres_trial_promo)

By the same author (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

PART I (#ulink_cf7c1a8a-7105-53ed-acb3-e7dc3592dac1)

Chapter One (#ulink_251837ea-c725-511e-9cd1-e2185b33b683)

There were few streets in the main port of Sydney which deserved the name, besides the one main thoroughfare, and even that bare packed dirt, lined only with a handful of small and wretched buildings that formed all the permanence of the colony. Tharkay turned off from this and led the way down a cramped, irregularly arranged alleyway between two wooden-slat buildings to a courtyard full of men drinking, in surly attitudes, with no roof but a tarpaulin.

Along one side of the courtyard, the further from the kitchens, the convicts sat in their drab and faded duck trousers, dusty from the fields and quarries and weighted down with fatigue; along the other, small parties of men from the New South Wales Corps watched with candidly unfriendly faces as Laurence and his companions seated themselves at a small table near the edge of the establishment.

Besides their being strangers, Granby’s coat drew the eye:bottle-green was not in the common way, and though he had put off the worst excesses of gold braid and buttons with which Iskierka insisted upon adorning him, the embroidery at cuffs and collar could not be so easily detached. Laurence wore plain brown, himself: to make a pretence of standing in the Aerial Corps now was wholly out of the question, of course, and if his dress raised questions concerning his situation, that was certainly no less than honest, as neither he nor anyone else had yet managed to work out what that ought in any practical sense to be.

‘I suppose this fellow will be here soon enough,’ Granby said, unhappily; he had insisted on coming, but not from any approval of the scheme.

‘I fixed the hour at six,’ Tharkay answered, and then turned his head: one of the younger officers had risen from the tables and was coming towards them.

Eight months aboard ship with no duties of his own and shipmates nearly united in their determination to show disdain had prepared Laurence for the scene which, with almost tiresome similarity, unfolded yet again. The insult itself was irritating for demanding some answer, more than anything else; it had not the power to wound in the mouth of a coarse young boor, stinking of rum and visibly unworthy to stand among even the shabby ranks of a military force alternately called the Rum Corps. Laurence regarded Lieutenant Agreuth only with distaste, and said briefly, ‘Sir, you are drunk; go back to your table, and leave us at ours.’

There the similarity ended, however: ‘I don’t see why I,’ Agreuth said, his tongue tangling awkwardly, so he had to stop and repeat himself, speaking with excessive care, ‘why I should listen to anything out of a piss-pot whoreson traitor’s fucking mouth—’

Laurence stared, and heard the tirade with mounting incredulity; he would have expected the gutter language out of a dockyard pickpocket in a temper, and hardly knew how to hear it from an officer. Granby had evidently less difficulty, and sprang to his feet saying, ‘By God, you will apologize, or for a ha’penny I will have you flogged through the streets.’

‘I would like to see you try it,’ Agreuth said, and leaning over spat into Granby’s glass; Laurence stood too late to catch Granby’s arm from throwing it into Agreuth’s face.

That was of course an end to even the barest hope or pretence of civility; Laurence instead pulled Granby back by his arm, out of the way of Agreuth’s wildly swinging fist, and letting go struck back with the same hand, clenched, as it came again at his face.

He did not hold back; if brawling was outrageous, it looked inevitable, and he would as soon have it over with quickly. So the blow was armed with all the strength built up from childhood on rope-lines and harness, and Laurence knocked Agreuth directly upon the jaw: the lieutenant lifted half an inch from the ground, his head tipping back and leading the rest of his frame. Stumbling a few steps as he came down, he pitched face-front onto the floor straight through the neighbouring table, to the accompaniment of several shattering glasses and the stink of cheap rum.

That might have been enough, but Agreuth’s companions, though officers and some of them older and more sober than he, showed no reluctance in flinging themselves at once into the fray thus begun. The men at the overturned table, sailors on an East India merchantman, were as quick to take offence at the disruption of their drinking; and a mingled crowd of sailors and labourers and soldiers, all better than three-quarters of the way drunk, and a great scarcity of women, as compared to what would have been found in nearly every other dockyard house of the world which Laurence knew, was a powder keg ready for the slow match in any case. The rum had not finished sinking between the paving stones before men were rising from their chairs all around them.

Another officer of the New South Wales Corps threw himself on Laurence: a bigger man than Agreuth, sodden and heavy with liquor. Laurence twisted himself loose and heaved him down onto the floor, shoving him as well as could be managed under the table. Tharkay was already with a practical air seizing the bottle of rum by the neck, and when another man lunged ‐ this one wholly unconnected with Agreuth, and by all appearances simply pleased to fight anyone at all – Tharkay clubbed him upon the temple swiftly.

Granby had been seized upon by three men at once: two of them, Agreuth’s fellows, for spite, and one who was trying his best only to get at the jewelled sword and belt around his waist. Laurence struck the pickpocket on the wrist, and seizing him by the scruff of the collar flung him stumbling across the courtyard; Granby exclaimed, then, and turning back Laurence found him ducking from a knife, dirty and rust-speckled, being stabbed at his eyes.

‘By God, have you taken all leave of your senses?’ Laurence said, and seized upon the knife-wielder’s hand with both his own, twisting the blade away, while Granby efficiently knocked down the third man and turned back to help him. The melee was spreading rapidly now, helped along by Tharkay, who was coolly throwing the toppled chairs across the room, knocking over still more of the tables, and flinging glasses of rum into the faces of the custom as they rose indignantly.

Laurence and Granby and Tharkay were only three together, and thanks to the advance of the New South Wales officers well-surrounded, leaving the irritated men no other target but those same officers; a target on which the convicts in particular seemed not loath to vent their spleen. This was not a very coherently directed fury, however, and when the officer before Laurence had been clubbed down with a heavy stool, the choleric assailant behind him swung it with equal fervour at Laurence himself.

Laurence slipped upon the wet floorboards, catching the stool away from his face, and went to one knee in a puddle. He shoved the man’s leg out from under him, and was rewarded with the full weight of man and stool landing upon his shoulder, so they went sprawling together upon the floor.

Splinters drove into Laurence’s side, where his shirt had ridden up from his breeches and come wholly loose, and the big convict, swearing at him, struck him upon the side of his face with a clenched fist. Laurence tasted blood as his lip tore upon his tooth, a dizzying haze over his sight. They were rolling across the floor, and Laurence had no very clear recollection of the next few moments; he was pounding at the other man savagely, a blow with every turn, knocking his head against the boards over and over. It was a vicious, animal struggle, insensible of both feeling and thought; he knew only distantly as he was kicked, by accident, or struck against the wall or some overturned piece of furniture.

The limp unconsciousness of his opponent freed him at last from the frenzy, and Laurence with an effort opened his clenched hand and let go the man’s hair, and pushed himself up from the floor, staggering. They had fetched up against the wooden counter before the kitchen. Laurence reaching up clutched at the edge and pulled himself to his feet, aware more than he wished to be, all at once, of a deep stabbing pain in his side, and stinging cuts in his cheek and his hands. He fumbled at his face and pulled a long sliver of broken glass free, tossing it upon the counter.

The fighting was beginning already to die down – not the length of an engagement, on the deck of a ship, where there was something to be gained. Laurence limping across the room made it to Granby’s side: Agreuth and one of his fellow officers had clawed their way back up onto their feet and were yet grappling weakly with him in a corner, vicious but half-exhausted, so they were swaying back and forth more than wrestling.

Coming in, Laurence heaved Granby free, and leaning on each other they stumbled out of the courtyard and into the narrow, stinking alleyway outside, which yet seemed cool and fresh out from under the makeshift tarpaulin roof; a fine misting rain was falling. Laurence leaned gratefully against the far wall made cool and light by the coating of dew, ignoring with a practised stomach the man a few steps away who was heaving the contents of his belly into the gutters. A couple of women coming down the alleyway lifted their skirts over the trickle of muck and continued on past them all without hesitation, not even looking in at the disturbance of the tavern courtyard.

‘My God, you look a fright,’ Granby said, dismally.

‘I have no doubt,’ Laurence said, gingerly touching at his face. ‘And I have two ribs cracked, I dare say. I am sorry to say, John, you are not in much better case.’

‘No, I am sure not,’ Granby said. ‘We will have to take a room somewhere, if anyplace will let us through the door, to wash up; what Iskierka would do seeing me in such a state, I have no notion.’

Laurence had a very good notion what Iskierka would do, and also Temeraire, and between them there would not be much left of the colony to speak of afterwards.

‘Well,’ Tharkay said, joining them as he wrapped his neck-cloth around his own bloodied hand, ‘I believe I saw our man look into the establishment, a little while ago, but I am afraid he thought better of coming in under the circumstances. I will have to inquire after him to arrange another meeting.’

‘No,’ Laurence said, blotting his lip and cheek with his handkerchief. ‘No, I thank you; I think we can dispense with his information. I have seen all I need to, in order to form an opinion of the discipline of the colony, and its military force.

‘Temeraire sighed and toyed with the last bites of kangaroo stew – the meat had a pleasantly gamy sort of flavour, not unlike deer, and he had found it at first a very satisfying change from fish, after the long sea-voyage. But he could only really call it palatable when cooked rare, which did not offer much variety, and in stew it became quite stringy and tiresome, especially as the supply of spice left even more to be desired.

There were some very nice cattle in a pen which he could see, from his vantage upon the harbour promontory, but evidently they were much too dear here for the Corps to provide. And Temeraire of course could not propose such an expense to Laurence, not when he had been responsible for the loss of Laurence’s fortune; instead Temeraire had at once silenced all his mild complaints about the lack of variety: but sadly Gong Su had taken this as encouragement, and it had been nothing but kangaroo morning and night, four days running – not even a bit of tunny.

‘I do not see why we mayn’t at least go hunting further along,’ Iskierka said, even while licking out her own bowl indecorously – she quite refused to learn anything resembling polite manners. ‘This is a large country, and it stands to reason there ought to be something more worth eating if we looked. Perhaps there are some of those elephants which you have been on and on about; I should like to try one of those.’

Temeraire would have given a great deal for a delicious elephant, seasoned with a generous amount of pepper and perhaps some sage, but Iskierka was never to be encouraged in anything whatsoever. ‘You are very welcome to go flying away anywhere you like,’ he said, ‘and to surely get quite lost. No one has any notion of what this countryside is like, past the mountains, and there is no one in it, either, to ask for directions: not people or dragons.’

‘That is very silly,’ Iskierka said. ‘I do not say these kangaroos are very good eating, because they are not, and there are not enough of them, either; but they are certainly no worse than what we had in Scotland during the last campaign, so it is stuff to say there is no one living here; why wouldn’t there be? I dare say there are plenty of dragons here, only they are somewhere else, eating much better than we are.’

This struck Temeraire as not an unlikely possibility, and he made a note to discuss it privately with Laurence, later; which recalled him to Laurence’s absence, and thence to the advancing hour. ‘Roland,’ he called, with a little anxiety – of course Laurence did not need nursemaiding, but he had promised to return before the supper hour and read a little more of the novel which he had acquired in town the day before. ‘Roland, is it not past five?’

‘Lord, yes, it must be almost six,’ Emily Roland answered, putting down her sword; she and Demane were fencing a little, in the yard. She wiped her face with a tugged-free tail of her shirt, ran to the promontory edge to call down to the sailors below, and came back to say, ‘No, I am wrong: it is a quarter past seven: how strange the day is so long, when it is almost Christmas!’

‘It is not strange at all,’ Demane said. ‘It is only strange that you keep insisting it must be winter here only because it is in England.’

‘But where is Granby, if it is so late?’ Iskierka said, prickling up at once, overhearing. ‘He did not mean to go anywhere particularly nice, he assured me, or I should never have let him go looking so shabby.’

Temeraire flared his ruff a little, taking this to heart; he felt it keenly that Laurence should go about in nothing but a plain gentleman’s coat, without even a little bit of braid or golden buttons. He would gladly have improved Laurence’s appearance if he had any chance of doing so; but Laurence still had refused to sell Temeraire’s talon sheaths for him, and even if he had, Temeraire had not yet seen anything in this part of the world which would have suited him as appropriate.

‘Perhaps I had better go and look for Laurence,’ Temeraire said. ‘I am sure he cannot have meant to stay away so long.’

‘I am going to go and look for Granby, too,’ Iskierka announced.

‘Well, we cannot both go,’ Temeraire said irritably. ‘Someone must stay with the eggs.’ He cast a quick, judgmental eye over the three eggs in their protective nests of swaddling blankets, and the small canopy set over them, made of sailcloth. He was a little dissatisfied by their situation: a nice little coal brazier, he thought, would not have gone amiss even in this warm weather, and perhaps some softer cloth to go directly against the shell; and it did not suit him that the canopy was so low he could not put his head underneath it, to sniff at the eggs and see how hard their shells had become.

There had been a little difficulty over them, after disembarking: some of the officers of the Corps who had been sent along had tried to object to Temeraire’s keeping the eggs by him, as though they would be better able to protect them, which was stuff; and they had made some sort of noise about Laurence trying to kidnap the eggs, which Temeraire had snorted off.

‘Laurence does not want any other dragon, as he has me,’ Temeraire had said, ‘and as for kidnapping, I would like to know whose notion it was to take the eggs halfway across the world on the ocean, with storms and sea serpents everywhere, and to this odd place that is not even a proper country, with no dragons; it was certainly not mine.’

‘Mr. Laurence is going directly to hard labour, like all the rest of the prisoners,’ Lieutenant Forthing had said, quite stupidly, as though Temeraire were allowing any such thing to happen.

‘That is quite enough, Mr. Forthing,’ Granby had said, overhearing, and coming upon them. ‘I wonder that you would make any such ill-advised remark; I pray you take no notice of it at all, Temeraire, none at all.’

‘Oh! I do not in the least,’ Temeraire answered, ‘or any of these other complaints; it is all nonsense, when what you mean is,’ he added to Forthing and his associates, ‘you would like to keep the eggs by you, so that they should not know any better when they hatch, but think they must go at once into harness, and that they must take whichever of you wins them by chance: I heard you talk of drawing lots last night in the gunroom, so you needn’t try and deny it. I will certainly have none of it, and I expect neither will the eggs, of any of you.’

He had of course carried his point, and the eggs, away to their present relative safety and comfort, but Temeraire had no illusions as to the trustworthiness of people who could make such spitefully false remarks; he did not doubt that they would try and creep up and snatch the eggs away if he gave them even the least chance. He slept curled about the tent, therefore, and Laurence had put Roland and Demane and Sipho on watch, also.

The responsibility was proving sadly confining, however, particularly as Iskierka was not to be trusted with the eggs for any length of time. Fortunately the town was very small, and the promontory visible from nearly any point within it if one only stretched out one’s neck to look, so Temeraire felt he might risk it, only long enough to find Laurence and bring him back. Of course Temeraire was sure no one would be absurd enough to try and treat Laurence with any disrespect, but it could not be denied that men were inclined to do unaccountable things from time to time, and Forthing’s remark stirred uneasily in the back of his head.

It was true, if one wished to be very particular about such things, that Laurence was a convicted felon: convicted of treason, and his sentence only commuted to transportation at the behest of Lord Wellington, after the last campaign in England. But that sentence had been fulfilled, in Temeraire’s opinion: no one could deny that Laurence had now been transported, and the experience had been quite as much punishment as anyone could have wished.

The unhappy Allegiance had been packed to the portholes with still-more-unhappy convicts, who had been kept chained wrist and ankle all the day, and stank quite dreadfully whenever they were brought out for exercise in their clanking lines, some of them hanging limp in the restraints. It seemed quite like slavery, to Temeraire; he did not see why it should make so vast a difference as Laurence said, only because a lawcourt had said the poor convicts had stolen something: after all, anyone might take a sheep or a cow, if it were neglected by its owner and not kept under watch.

Certainly it made the ship as bad as any slaving vessel: the smell rose up through the planking of the deck, and the wind brought it forward to the dragondeck almost without surcease; even the aroma of boiling salt pork, from the galley below, could not erase it. And Temeraire had learned by accident, perhaps a month out on their journey, that Laurence was quartered directly by the gaol, where it must have been far worse.

Laurence had dismissed the notion of making any complaint, however. ‘I do very well, my dear,’ he had said, ‘as I have the whole liberty of the dragondeck for my days and the pleasanter nights, which not even the ship’s officers have. It would be unfair in the extreme, when I have not their labour, for me to be demanding some better situation: someone else would have to shift places to give me another.’

So it had been a very unpleasant transportation indeed, and now they were here, which no one could enjoy, either. Aside from the question of kangaroos, there were not very many people at all, and nothing like a proper town. Temeraire was used to seeing wretched quarters for dragons, in England, but here people did not sleep much better than the clearings in any covert, many of them in tents or makeshift little buildings which did not stay up when one flew over them, not even very low, and instead toppled over and spilled out the squalling inhabitants to make a great fuss.

And there was no fighting to be had at all, either. Several letters and newspapers had reached them along the way, when quicker frigates passed the labouring bulk of the Allegiance, and it was very disheartening to Temeraire to have Laurence read to him how Napoleon was reported to be fighting again, in Spain this time, and sacking cities all along the coast, and Lien surely with him: and meanwhile here they were on the other side of the world, uselessly. It was not in the least fair, Temeraire thought disgruntled, that Lien, who did not think Celestials ought to fight ever, should have all the war to herself while he sat here nursing eggs.

There had not even been a small engagement at sea, for consolation: they had once seen a French privateer, off at a distance, but the small vessel had set every scrap of sail and vanished away at a heeling pace. Iskierka had given chase anyway, alone – as Laurence pointed out to Temeraire he could not leave the eggs for such a fruitless adventure – and to Temeraire’s satisfaction, after a few hours she had been forced to return empty-handed.

The French would certainly not attack Sydney, either; not when there was nothing to be won but kangaroos and hovels. Temeraire did not see what they were to do here, at all; the eggs were to be seen to during their hatching, but that could not be far off, he felt sure, and then there would be nothing to do but sit about and stare out to sea.

The people were all engaged either in farming, which was not very interesting, or they were convicts, who, it seemed to Temeraire, marched out in the morning for no reason and then marched back at night. He had flown after them one day, just to see, and had discovered they were only going to a quarry to cut out bits of stone, and were then bringing the bits of stone back to town in wagon-carts, which seemed quite absurd and inefficient: he could have carried five cartloads in a single flight of perhaps only ten minutes; but when Temeraire had landed to offer his assistance, the convicts had all run away, and the soldiers had complained to Laurence stiffly afterwards.

They certainly did not like Laurence; one of them had been very rude, and said, ‘For five pence I would have you down at the quarries, too,’ at which Temeraire put his head down and said, ‘For two pence I will have you in the ocean; what have you done, I should like to know, when Laurence has won a great many battles with me, and we drove Napoleon off; and you have only been sitting here. You have not even managed to raise a respectable number of cows.’

Temeraire now felt perhaps that jibe had been a little injudicious, or perhaps he ought not to have let Laurence go into town, after all, when there were people who wished to put him into quarries. ‘I will go and look for Laurence and Granby,’ he said to Iskierka, ‘and you will stay here: if you go, you will likely set something on fire, anyway.’

‘I will not set anything on fire!’ Iskierka said. ‘Unless it needs setting on fire, to get Granby out.’

‘That is just what I mean,’ Temeraire said. ‘How, pray tell, would setting something on fire do any good at all?’

‘If no one would tell me where he was,’ Iskierka said, ‘I am quite sure that if I set something on fire and told them I would set the rest on fire too, they would come about: so there.’

‘Yes,’ Temeraire said, ‘and in the meanwhile, very likely he would be in whatever house you had set on fire, and be hurt: and if not, the fire would jump along to the nearby buildings whether you liked it to or not, and he would be in one of those. Whereas I will just take the roof off a building, and then I can look inside and lift them out, if they are in there, and people will tell me anyway.’

‘I can take a roof off a building, too!’ Iskierka said. ‘You are only jealous, because someone is more likely to want to take Granby, because he has more gold on him and is much more fine.’

Temeraire swelled with indignation and breath, and would have expelled them both in a rush, but Roland interrupted urgently, saying, ‘Oh, don’t quarrel! Look, here they are all coming back, right as rain: that is them on the road, I am sure.’

Temeraire whipped his head around: three small figures had just emerged from the small cluster of buildings which made the town, and were on the narrow cattle track which came towards the promontory.

Temeraire and Iskierka’s heads were raised high, looking down towards them; Laurence raised a hand and waved vigorously, despite the twinge in his ribs, which a bath and a little rough bandaging had not gone very far to alleviate; that injury, however, could be concealed. ‘There; at least we will not have them down here in the streets,’ Granby said, lowering his own arm, and wincing a little; he probed gingerly at his shoulder.

It was still a near-run thing when they had reached the promontory – a slow progress, and Laurence’s legs wished to quiver on occasion, before they had reached the top and could sit on the makeshift benches. Temeraire sniffed, and then lowered his head abruptly and said, ‘You are hurt; you are bleeding,’ with urgent anxiety.

‘It is nothing to concern you; I am afraid we only had a little accident in the town,’ Laurence said, guiltily preferring a certain degree of deceit to the inevitable complications of Temeraire’s indignation.

‘So, dearest, you see it is just as well I wore my old coat,’ Granby said to Iskierka, in a stroke of inspiration, ‘as it has got dirty and torn, which you would have minded if I had on something nicer.’

Iskierka was thus diverted to a contemplation of his clothing, instead of his bruises, and promptly pronounced it a natural consequence of the surroundings. ‘If you will go into a low, wretched place like that town, one cannot expect anything better,’ she said, ‘and I do not see why we are staying here, at all; I think we had better go straight back to England.’

Chapter Two (#ulink_3c5c9b1c-fb78-51f9-b3bb-fd40c29710f3)

‘I am not surprised in the least,’ Bligh said, ‘in the least; you see exactly how it is now, Captain Laurence, with these whoreson dogs and Merinos.’

His language was not much better than that of the aforementioned dogs, and neither could Laurence much prefer his company. He did not like to think so of the King’s governor and a Navy officer, and particularly not one so much a notable seaman: his feat of navigating 3600 miles of open ocean in only a ship’s launch, when left adrift by the Bounty, was still a prodigy.

Laurence had looked at least to respect, if not to like; but the Allegiance had stopped to take on water in Van Diemen’s Land, and there found the governor they had confidently expected to meet in Sydney, deposed by the Rum Corps and living in a resentful exile. He had a thin, soured mouth, perhaps the consequence of his difficulties; a broad forehead exposed by his receding hair and delicate, anxious features beneath it, which did not very well correspond with the intemperate language he was given to unleash on those not uncommon occasions when he felt himself thwarted.

He had no recourse but to harangue passing Navy officers with demands to restore him to his post, but all of those prudent gentlemen, to date, had chosen to stay well out of the affair while the news took the long sea-road back to England for an official response. This, Laurence supposed, had been neglected in the upheaval of Napoleon’s invasion and its aftermath; nothing else could account for so great a delay. But no fresh orders had come, nor a replacement governor, and meanwhile in Sydney the New South Wales Corps, and those men of property who had promoted their coup, grew all the more entrenched.

The very night the Allegiance put into the harbour, Bligh had himself rowed out to consult with Captain Riley; he had very nearly asked himself to dinner, and directed the conversation with perfect disregard for Riley’s privilege; though as a Navy man himself he could not be ignorant of the custom.

‘A year now, and no answer,’ Bligh had said in a cloud of spittle and fury, waving his hand to Riley’s steward to send the bottle round to him again. ‘A full year gone, Captain, and meanwhile in Sydney these scurrilous worms yet inculcate all the populace with licentiousness and sedition: it is nothing to them, nothing, if every child born to woman on these shores should be a bastard and a bugger and a drunken leech, so long as they do a little work upon their farms, and lie quiet under the yoke: let the rum flow is their only maxim, the liquor their only coin and god.’ He did not, however, stint himself of the wine, near-vinegar though it was, nor the last dregs of Riley’s port; ate well, also, as might a man living mostly on hardtack and a little occasional game.

Laurence, silent, rolling the stem of his glass between his fingers, could not but feel some sympathy: a little less of self-restraint, and he might have railed with as much fervour, against the cowardice and stupidity which had united to send Temeraire into exile. He too wished to be restored, if not to rank or to society, at least to a place where they might be useful; and not to merely sit here on the far side of the world upon a barren rock, and complain unto heaven.

But now Bligh’s downfall might as easily be his own: his one hope of return had been a pardon from the colony’s governor, for himself and Temeraire; or at least enough of a good report to reassure those in England whose fears and narrow interest had seen them sent away.

It had always been a scant hope, a little threadbare; but Jane Roland certainly wished for the return of Britain’s one Celestial, when she had Lien to contend with on the enemy’s side. Laurence might have some hope that the nearly superstitious fear of the breed which had sprung up, after the dreadful carnage of Lien’s attack upon the Navy, at the battle of Shoeburyness, was beginning to subside, and cooler minds regret the impulse which had sent away so valuable a weapon.

At least, so she had written, encouragingly; and had advised him, ‘I may have a prayer of sending the Viceroy to fetch you home, when she has been refit; only for God’s sake be obliging to the Governor, if you please; and I will thank you not to make any more great noise of yourself: it would be just as well if there is not a word to be said of you in the next reports from the colony, good or evil, but that you have been meek as milk.’

Of that, however, there was certainly no hope, from the moment when Bligh had blotted his lips and thrown down his napkin and said, ‘I will not mince words, Captain Riley: I hope you see your duty clear under the present circumstances, and you as well, Captain Granby,’ he added.

This was, of course, to carry Bligh back to Sydney, there to threaten the colony with bombardment or pillage, at which the ringleaders MacArthur and Johnston would be handed over for judgment. ‘And to be summarily hanged like the mutinous scoundrels they are, I trust,’ Bligh said. ‘It is the only possible repair for the harm which they have done: by God,I should like to see their worm-eaten corpses on display a year and more, for the edification of their fellows; then we may have a little discipline again.’

‘Well, I shan’t,’ Granby said, incautiously blunt, ‘and,’ he added to Laurence and Riley privately, afterwards, ‘I don’t see as we have any business telling the colony they shall have him back: it seems to me after a fellow has been mutinied against three or four times, there is something to it besides bad luck.’

‘Then you shall take me aboard,’ Bligh said, scowling when Riley had also made his more polite refusal. ‘I will return with you to England, and there present the case directly; so far, I trust, you cannot deny me,’ he asserted, with some truth: such a refusal would have been most dangerous politically to Riley, whose position was less assured than Granby’s, and unprotected by any significant interest. But Bligh’s real intention, certainly, was to return not to England but to the colony, in their company and under Riley’s protection with the intention meanwhile of continuing his attempts at persuasion however long they should remain there in port.

It was not to be supposed that Laurence could put himself at Bligh’s service, in that gentleman’s present mood, without at once being ordered to restore him to his office and to turn Temeraire upon the rebels. Even if such a course should serve Laurence’s self-interest, it was wholly inimical to his every feeling. He had allowed himself and Temeraire to be so used once – by Wellington, against the French invaders during Britain’s greatest extremity; it had still left the blackest taste in his mouth, and he would never again so submit.

Yet equally, if Laurence put himself at the service of the New South Wales Corps, he became nearly an assistant to mutiny. It required no great political gifts to know this was of all accusations the one which he could least afford to sustain, and the one which would be most readily believed and seized upon by his enemies and Temeraire’s, to deny them any hope of return.

‘I do not see the difficulty; there is no reason why you should surrender to anyone,’ Temeraire said obstinately, when Laurence had in some anxiety raised the subject with him aboard ship as they made the trip from Van Diemen’s Land to Sydney: the last leg of their long voyage, which Laurence formerly would have advanced with pleasure, and now with far more pleasure would have delayed. ‘We have done perfectly well all this time at sea, and we will do perfectly well now, even if a few tiresome people have been rude.’

‘Legally, I have been in Captain Riley’s charge, and may remain so a little longer,’ Laurence answered. ‘But that cannot answer for very long: ordinarily he ought to discharge me to the authorities with the rest of the prisoners.’

‘Whyever must he? Riley is a sensible person,’ Temeraire said, ‘and if you must surrender to someone, he is certainly better than Bligh. I cannot like anyone who will insist on interrupting us at our reading, four times, only because he wishes to tell you yet again how wicked the colonists are and how much rum they drink: why that should be of any interest to anyone I am sure I do not know.’

‘My dear, Riley will not long remain with us,’ Laurence said. ‘A dragon transport cannot simply sit in harbour; this is the first time one has been spared to this part of the world, and that only to deliver us. When she has been scraped, and the mizzen topmast replaced, from that blow we had near the Cape, they will go; I am sure Riley expects fresh orders very nearly from the next ship into harbour behind us.’

‘Oh,’ Temeraire said, a little downcast, ‘and we will stay, I suppose.’

‘Yes,’ Laurence said, quietly. ‘I am sorry.’

And without transport, Temeraire would be quite truly a prisoner of their new situation: there were few ships, and none of merchant class, which could carry a dragon of Temeraire’s size, and no flying route which could safely see him to any other part of the world. A light courier, built for endurance, perhaps might manage it in extremis with a well-informed navigator, clear weather, and luck, setting down on some deserted and rocky atolls for a rest; but the Aerial Corps did not risk even them on any regular mission to the colony, and Temeraire could never follow such a course without the utmost danger.

And if any degree of persuasion on Granby’s part could manage it, he and Iskierka would go as well, when Riley did, to avoid a similar entrapment; leaving Temeraire quite isolated from his own kind, save for the three prospective hatchlings who were as yet an unknown quantity.

‘Well, that is nothing to be sorry for,’ Temeraire said, rather darkly eyeing Iskierka, who at present was asleep and exhaling quantities of steam from her spikes upon his flank, which gathered into fat droplets and rolled off to soak the deck beneath him. ‘Not,’ he added, ‘that I would object to company; it would be pleasant to see Maximus again, and Lily, and I would like to know how Perscitia is getting on with her pavilion; but I am sure they will write to me when we are settled, and as for her, she may go away any time she likes.’

Laurence felt Temeraire might find it a heavier penalty to be exacted than he yet knew. Yet the prospect of these miseries, which had heretofore on their journey greatly occupied his concerns, seemed petty in comparison with the disaster of the situation that now awaited them: trapped in the roles of convict and kingmaker both, and without any means of escape, save if they chose to sacrifice all intercourse with society and take themselves off into the wilderness.

‘Pray do not worry, Laurence,’ Temeraire said stoutly. ‘I am sure we will find it a very interesting place, and anyway,’ he added, ‘at least there will be something nicer to eat.’

Their reception, however, had if anything only given more credence to Bligh’s representations, and Laurence’s anxiety. The Allegiance could not be said to have crept up on the colony: she had entered the mouth of the harbour at eleven in the morning on a brilliantly clear day, with only the barest breath of wind to bring her along. After eight months at sea, all of them might have been pardoned for impatience, but no one could be immune to the almost shocking loveliness of the immense harbour: one bay after another curving off the main channel, and the thickly forested slopes running down to the water, interspersed with stretches of golden sand.

So Riley did not order out the boats for rowing, or even try to spread a little more sail; he let the men mostly hang along the rail, looking at the new country before them while the Allegiance stately glided among the smaller shipping like a great finwhale among clouds of baitfish. Nearly three hours of slow, clear sailing before they lowered the anchor, then, but still there was no welcome come to meet them.

‘I will fire a salute, I suppose,’ Riley said, doubtfully; and the guns roared out. Many of the colonists in their dusty streets turned to look, but still no answer came, until after another two hours at last Riley put a boat over the side, and sent Lord Purbeck, his first lieutenant, ashore.

Purbeck returned shortly to report he had spoken with Major Johnston, the present chief of the New South Wales Corps, but that gentleman refused to come aboard so long as Bligh was present: the intelligence of Bligh’s return had evidently reached Sydney in advance, likely by some smaller, quicker ship making the same passage from Van Diemen’s Land.

‘We had better go see him ourselves, then,’ Granby said, quite unconscious of the appalled looks Laurence and Riley directed at him, at the proposal that a Navy captain should lower himself to call upon an Army major, who had behaved so outrageously and ungentlemanly, and unfortunately added, ‘It don’t excuse him, but I would not have put it past that fellow Bligh to send word ahead himself that we were here to put him back in his place,’ sadly plausible; and to make matters worse, there was little alternative. Their stores were running low, and that was no small matter with the hold crammed full of convicts, and the deck weighted down with dragons.

Riley went stiffly, with a full complement of Marines, and invited Laurence and Granby both to accompany him. ‘It may not be regular, but neither is anything else about this damned mess,’ he said to Laurence, ‘and I am afraid you will need to get the measure of the fellow, more than any of us.’

It was not long in coming: ‘If you mean to try and put that cowering snake over us again, I hope you are ready to stay, and swallow his brass with us,’ Johnston said, ‘for an you go away, we’ll have him out again in a trice; for my part, I will answer to anyone who has a right to ask it for what I have done, which isn’t any of you.’

These were the first words uttered, preceding even introduction, as soon as they had been shown into his presence: not into an office, but only the antechamber in the single long building which served for barracks and headquarters both.

‘What that has to do with hailing a King’s ship properly when it comes into harbour, I would like to know,’ Granby said heatedly, responding in kind, ‘and I don’t care two pence for Bligh or you, either, until I have provision for my dragon; which you had better care about, too, unless you like her to help herself.’

This exchange had not made the welcome grow particularly warmer: even apart from the suspicion of their assisting Bligh, Johnston was evidently uneasy for all his bluster, as well might he and his fellows be with their present arrangements, at once illegal and unsettled, with so long a silence from England. Laurence might have felt some sympathy for that unease, under other circumstances: the Allegiance and her dragon passengers came into the colony as an unknown factor, and with the power of disrupting all the established order.

But the first sight of the colony had already shocked him very much: in this beautiful and lush country, to find such a general sense of malaise and disorder, women and men staggering-drunk in the streets even before the sun had set, and for most of the inhabitants thin ramshackle huts and tents the only shelters. Even these were occupied irregularly: as they walked towards their unsatisfactory meeting, and passed one such establishment with no door whatsoever, Laurence glanced and was very shocked to see within a man and a woman copulating energetically, he still half in military uniform, while another man snored sodden upon the floor and a child sat dirty and snuffling in the corner.

More distressing still was the bloody human wreckage on display at the military headquarters, where an enthusiastic flogger seemed to scarcely pause between his customers, a line of men shackled and sullen, waiting for fifty lashes or a hundred – evidently their idea of light punishment.

‘If I would not soon have a mutiny of my own,’ Riley said, half under his breath, as they returned to the Allegiance, ‘I would not let my men come ashore here for anything; Sodom and Gomorrah are nothing to it.’

Three subsequent weeks in the colony had done very little to improve Laurence’s opinion of its present or its former management. There was nothing in Bligh himself which could be found sympathetic: in language and manner he was abrupt and abrasive, and where his attempts to assert authority were balked, he turned instead to a campaign of ill-managed cajolery, equal parts insincere flattery and irritated outbursts, which did little to conceal his private conviction of his absolute righteousness.

But this was worse than any ordinary mutiny: he had been the royal governor, and the very soldiers responsible for carrying out his orders had betrayed him. Riley and Granby continuing obdurate, and likely soon to be gone, Bligh had fixed upon Laurence as his most promising avenue of appeal, and refused to be deterred; daily now he would harangue Laurence on the ill-management of the colony, the certain evils flowing from permitting such an illegitimate arrangement to continue.

‘Have Temeraire throw him overboard,’ Tharkay had suggested laconically, when Laurence had escaped to his quarters for a little relief and piquet, despite the nearly stifling heat belowdecks: the open window let in only a still-hotter breeze. ‘He can fish him out again after,’ he added, as an afterthought.

‘I very much doubt if anything so mild as ocean water would prove effective at dousing that gentleman’s ardour for any prolonged time,’ Laurence said, indulging from temper in a little sarcasm: Bligh had gone so far today as to overtly speak of his right, if restored, to grant full pardon, and Laurence had been forced to quit him mid-sentence to avoid taking insult at this species of attempted bribery. ‘It might nearly be easier,’ he added more tiredly, the moment of heat past, ‘if I did not find some justice in his accusations.’

For the evils of the colony’s arrangements were very great, even witnessed at the remove of their shipboard life. Laurence had understood that the convicts were generally given sentences of labour, which being accomplished without further instance of disorder yielded their emancipation and the right to a grant of land: a thoughtful design envisioned by the first governor, intended to render them and the country both settled. But over the course of the subsequent two decades, this had remained little more than a design, and in practice nearly all the men of property were the officers of the New South Wales Corps or their former fellows.

The convicts at best they used as cheap labour; at worst, as chattels. Without prospects or connections to make them either interested in their future or ashamed of their behaviour, and trapped in a country that was a prison which needed no walls, the convicts were easily bribed to both labour and their own pacification with cheap rum, brought in at a handsome profit by the soldiers, and in such a way those who ought to have enforced order instead contributed to its decay, with no care for the disorder and self-destruction they thus engendered.

‘Or at least, so Bligh has argued, incessantly, and everything which I have seen bears him out,’ Laurence said. ‘But Tenzing, I cannot trust myself; I fear that I wish the complaints to be just, rather than know they are so. I am sorry to say it would be convenient to have an excuse to restore him.’

‘There is capot, I am afraid,’ Tharkay said, putting down his last card. ‘If you insist on achieving justice and not only convenience, you would learn more from speaking with some local citizen, a settled man, with nothing to complain of in his treatment on either side.’

‘If such a man is to be found, I can see no reason he would willingly confide his opinion, in so delicate a matter,’ Laurence said, throwing in, and gathering the cards up to sort out afresh.

‘I have letters of introduction to some few of the local factors,’ Tharkay said, a piece of news to Laurence, who wondered; so far as he knew, Tharkay had only come to New South Wales to indulge an inveterate wanderlust; but of course he could not intrude upon Tharkay’s privacy with a direct question.

‘If you like,’ Tharkay had continued, ‘I can make inquiries; and as for reason, if there is discontent enough to form the grounds for your decision, I would imagine that same discontent sufficient motive to speak.’

The attempt to pursue this excellent advice now having ended in public ignominy, however, Bligh was only too eager to take advantage and press Laurence further for action. ‘Dogs, Captain Laurence, dogs and cowardly sheep, all of them,’ Bligh said, ignoring yet again Laurence’s attempt to correct his address to Mr. Laurence; it would suit Bligh better, Laurence in exasperation supposed, to be restored by a military officer, and not a private citizen.

Bligh continued, ‘I imagine you can hardly disagree with me now. It is impossible you should disagree with me. It is the direct consequence of their outrageous usurpation of the King’s authority. What respect, what discipline, can possibly be maintained under a leadership so wholly devoid of just and legal foundation, so utterly lost to loyalty and—’

Here Bligh paused, perhaps reconsidering an appeal to the virtues of obedience, in the light of Laurence’s reputation; throwing his tiller over, however, Bligh without losing much time said instead, ‘and to decency; allow me to assure you this infamous kind of behaviour is general throughout the military ranks of the colony, indulged and indeed encouraged by their leaders.’

Fatigue and soreness at once physical and of the spirit had by now cut Laurence’s temper short: his ribs had grown swollen and very tender beneath the makeshift bandage; his hands ached a great deal, and what was worse, to no purpose: nothing gained but a sense of disgust. He was very willing to think ill of the colony’s leadership, of Johnston and MacArthur, but Bligh had not recommended himself, and his nearly gleeful satisfaction was too crassly, too visibly opportunistic.

‘I must wonder, sir,’ Laurence said, ‘how you would expect to govern, when you should be forced to rely upon those same soldiers whom you presently so disdain; having removed their ringleaders, who have preferred them to an extreme and given them so much license, how would you conciliate their loyalty, having been restored at the hands of one whom they already see as an outlaw?’

‘Oh! You give too much credit to their loyalty,’ Bligh said, dismissively, ‘and too little to their sense; they must know, of course, that MacArthur and Johnston are doomed. The length of the sea-voyage, the troubles in England, these alone have preserved them; but the hangman’s noose waits for them both, and as the time draws near, the advantages of their preferment lose their lustre. Some reassurances, some concessions: of course they may keep their land grants, and those appointments not made too ill may remain …’

He made a few more general remarks of this sort, with no better course of action envisioned on Bligh’s part, so far as Laurence could see, than to levy a series of new but only cosmetic restrictions, which should certainly only inflame men irritated by the overthrow, by an outsider and an enemy, of their tolerated if not necessarily chosen leadership.

‘Then I hardly see,’ Laurence said, not very politely, ‘precisely how you would repair these evils you condemn, which I cannot see were amended during your first administration; nor is Temeraire, as you seem to imagine, some sort of magical cannon which may be turned on anyone you like.’

‘If with this collection of mealy-mouthed objections you will excuse yourself from obliging me, Mr. Laurence,’ Bligh answered, deep colour spotting in the hollows of his cheeks, ‘I must count it another disappointment, and mark it against your character, such as that is,’ this with an acrid and unpleasant edge; and he left the dragondeck with his lips pressed tight and angry.

If Bligh followed in his usual mode, however, he would soon repent of his hasty words and seek another interview; Laurence knew it very well, and his feelings were sufficiently lacerated already that he did not care to be forced to endure the pretence of an apology, undoubtedly to be followed by a fresh renewal of those same arguments he had already heard and rejected.

He had meant to sleep aboard the ship, whose atmosphere had been greatly improved: the convicts having been delivered to the dubious embrace of the colony, Riley had set every one of his men to pumping the lower decks clean, sluicing out the filth and miasma left by several hundred men and women who had been afforded only the barest minimum of exercise and liberty essential to health. Smudges of smoke had been arranged throughout, and then a fresh round of pumping undertaken.

With the physical contamination thus erased, and the hovering and perpetual aura of misery, Laurence’s small quarters now made a comfortable if not luxurious residence by his standards, formed in his youth by the dimensions of a midshipman’s cot. Meanwhile the small shelter on the dragons’ promontory remained unroofed and as yet lacked its final wall, but Laurence felt bruised more in spirit than in body, and the weather held dry; he went below only to collect a few articles, and quitted the ship to seek refuge in Temeraire’s company.

In this mood, he was by no means prepared to be accosted on the track back up to the promontory, by a gentleman on horseback, of aquiline face, by the standards of the colony elegantly dressed and escorted by a groom, who leaned from his horse and demanded, ‘Am I speaking with Mr. Laurence?’

‘You have the advantage of me,’ Laurence said, a little rudely in his own turn; but he was not inclined to regret his curtness when the man said, ‘I am John MacArthur; I should like a word.’

There was little question he was the architect of the entire rebellion; and though he had arranged to be appointed Colonial Secretary, he had so far not even given Riley the courtesy of a call. ‘You choose odd circumstances for your request, sir,’ Laurence said, ‘and I do not propose to stand speaking in the dust of the street. You are welcome to accompany me to the covert, if you like; although I would advise you to leave your horse.’

He was a little surprised to find MacArthur willing to hand his reins to the groom, and dismount to walk with him. ‘I hear you had a little difficulty in the town today,’ MacArthur said. ‘I am very sorry it should have happened.

‘You must know, Mr. Laurence, we have had a light hand on the rein here; a light hand, and it has answered beautifully, beyond all reasonable hopes. Our colony does not show to advantage, you may perhaps think, coming from London; but I wonder what you would think if you had been here in our first few years. I came in the year 90; will you credit it, that there were not a thousand acres under cultivation, and no supply? We nearly starved, one and all, three times.’

He stopped and held out a hand, which trembled a little. ‘They have been so, since that first winter,’ he said, and resumed walking.

‘Your perseverance is to be admired,’ Laurence said, ‘and that of your fellows.’

‘If nothing else, that for certain sure,’ MacArthur said. ‘But it has not been by chance, or any easy road, that we have found success; only through the foresight of wise leadership and the strength of determined men. This is a country for a determined man, Mr. Laurence. I came here a lieutenant, with not a lick of property to my name; now I have 10,000 acres. I do not brag,’ he added. ‘Any man can do here what I have done. This is a fine country.’

There was an emphasis on any man, which Laurence found distasteful in the extreme; he read the slinking bribery in MacArthur’s pretty speech as easily as he had in Bligh’s whispers of pardon, and he pressed his lips together and stretched his pace.

MacArthur perceived his mistake, perhaps; he increased his own to match and said, to shift the subject, ‘But what does the Government send us? You have been a Navy officer yourself, Mr. Laurence; you have had the dregs of the prison-hulks, pressed into service; you know what I am speaking of. Such men are not formed for respectability. They can only be used, and managed, and to do it requires rum and the lash – it is the very understanding of the service. I am afraid it has made us all a little coarse here, however; we are ill-served by the proportion of our numbers. I wonder how you would have liked a crew of a hundred, five and ninety of them gaolbirds, and not five able seamen to your name.’

‘Sir, you are correct in this much; I have had a little difficulty, earlier in the day,’ Laurence said, pausing in the road; his ribs ached sharply in his side, ‘so I will be frank; you might have had conversation of myself, or of Captain Riley or Captain Granby, as it pleased you, these last two weeks, for the courtesy of a request. May I ask you to be a little more brief?’

‘Your reproach is a just one,’ MacArthur said, ‘and I will not tire you further tonight; if you will do me the kindness of returning my visit in the morning at the barracks?’

‘Forgive me,’ Laurence said dryly, ‘but I find I am not presently inclined to pay calls in this society; as yet I find the courtesies beyond my grasp.’

‘Then perhaps I may pay you another call,’ MacArthur suggested, if with slightly pressed lips, and to this Laurence could only incline his head.

‘I cannot look forward to the visit with any pleasure,’ Laurence said, ‘but if he comes, we ought to receive him.’

‘So long as he is not insulting, and does not try to put you in a quarry, he may come, if he likes,’ Temeraire said, making a concession, while privately determining he would keep a very close eye upon this MacArthur person; for his own part, he saw no reason to offer any courtesy at all to someone who was master of a place so wretchedly organized, and acquainted with so many ill-mannered people. Governor Bligh was not a very pleasant person, perhaps, but at least he did not seem to think it in the ordinary course of things for gentlemen to be knocked down in the street in mysterious accidents.

MacArthur did come, shortly after they had breakfasted. He drew up rather abruptly, reaching the top of the hill; Laurence had not yet seen him, but Temeraire had been looking over at the town – sixteen sheep were being driven into a pen – very handsome sheep – and he saw MacArthur pause, and halt, and look as though he might go away again.

Temeraire might have let him do so, and had a quiet morning of reading, but he had not enjoyed his meal and in a peevish humour said, ‘In my opinion it is quite rude to come into someone’s residence only to stare at them, and turn pale, and go, as if there were something peculiar in them, and not in such absurd behaviour. I do not know why you bothered to climb the hill at all, if you are such a great coward; it is not as though you did not know that I was here.’

‘Why, in my opinion, you are a great rascal,’ MacArthur said, purpling up his neck. ‘What do you mean by calling me a coward, because I need to catch my breath.’

‘Stuff,’ Temeraire said, roundly, ‘you were frightened.’

‘I do not say that a man hasn’t a right to be taken aback a moment, when he sees a beast the size of a frigate waiting to eat him,’ MacArthur said, ‘but I am damned if I will swallow this; you do not see me running away, do you?’

‘I would not eat a person,’ Temeraire said, revolted, ‘and you needn’t be disgusting, even if you do have no manners,’ to which Laurence coming around said, ‘So spake the pot,’ rather dryly.

He added, ‘Will you come and sit down, Mr. MacArthur? I regret I cannot offer you anything better than coffee or chocolate, and I must advise against the coffee,’ and Temeraire rather regretfully saw he had missed the opportunity to be rid of this unpleasant visitor.

MacArthur kept turning his head, to look at Temeraire, and remarked, ‘They don’t look so big, from below,’ as he stirred his chocolate so many times it must have grown quite cold. Temeraire was quite fond of chocolate, but he could not have that, either; not properly, without enough milk, and the expense so dear; it was not worth only having the tiniest taste, which only made one want more. He sighed.

‘Quite prodigious,’ MacArthur repeated, looking at Temeraire again. ‘He must take a great deal of feeding.’

‘We are managing,’ Laurence said politely. ‘The game is conveniently plentiful, and they do not seem to be used to being hunted from aloft.’

Temeraire considered that at least if MacArthur was here, he might be of some use. ‘Is there anything else to hunt, nearby?’ he inquired. ‘Not of course,’ he added untruthfully, ‘that anyone could complain of kangaroo.’

‘I am surprised if you have found any of those in twenty miles as the crow goes,’ MacArthur said. ‘We pretty near et up the lot, in the first few years.’

‘Well, we have been getting them around the Nepean River, and in the mountains,’ Temeraire said, and MacArthur’s head jerked up from his cup so abruptly that the spoon he had left inside it tipped over and spattered his white breeches with chocolate.

He did not seem to notice that he had made a sad mull of his clothing, but said thoughtfully, ‘The Blue Mountains? Why, I suppose you can fly all over them, can’t you?’

‘We have flown all over them,’ Temeraire said, rather despondently, ‘and there is nothing but kangaroo, and those rabbits that have no ears, which are too small to be worth eating.’

‘I would have been glad of a wombat or a dozen often enough, myself,’ MacArthur said, ‘but it is true we do not have proper game in this country, I am sorry to say I know from experience: too lean by half; you cannot keep up to fighting weight on it, and there is not enough grazing yet for cattle. We have not found a way through the mountains, you know,’ he added. ‘We are quite hemmed in.’

‘It is a pity no one has tried keeping elephants,’ Temeraire said.

‘Ha ha, keeping elephants, very good,’ MacArthur said, as if this were some sort of a joke. ‘Do elephants make good eating?’

‘Excellently good,’ Temeraire said. ‘I have not had an elephant since we were in Africa: I do not think I have tasted anything quite so good as a properly cooked elephant; outside of China, that is,’ he added loyally, ‘where I do not think they can raise them. But it seems as though this would be perfectly good country for them: it is certainly as hot as ever it was in Africa, where they raised them. Anyway we will need more food for the hatchlings, soon.’

‘Well, I have brought sheep, but I did not much think of bringing over elephants,’ MacArthur said, looking at the three eggs with an altered expression. ‘How much would a dragon eat, do you suppose, in the way of cattle?’

‘Maximus will eat two cows when he can get them, in a day,’ Temeraire said, ‘but I do not think that is very healthy; I would not eat more than one, unless of course I have been fighting, or flying far; or if I were very particularly hungry.’

‘Two cows a day, and soon to be five of you?’ MacArthur said. ‘The Lord safe preserve us.’

‘If this has brought you to a better understanding of the necessity of addressing the situation, sir,’ Laurence said, rather pointedly Temeraire thought, ‘I must be grateful for your visit; we have had very little cooperation heretofore in making our arrangements from Major Johnston.’

MacArthur put down his chocolate cup. ‘I was speaking last night, I think,’ he said, ‘of what a man can make of himself, in this country; it is a subject dear to my heart, and I hope I did not ramble on it too long. It is a hard thing, you will understand, Mr. Laurence, to see a country like this: begging for hands, for the ploughshare and the till, and no one to work it but an army of the worst slackabouts born of woman lying about, complaining if they are given less than their day’s half-gallon of rum, and they would take it at ten in the morning, if they could get it.

‘In the Corps, we may not be very pretty, but we know how to work; I believe the Aerial Corps, too, might be given such a character by some,’ MacArthur went on. ‘And we know how to make men work. Whatever has been built in this country, we ha’e built it, and to have a – perhaps I had better hold my tongue; I think you have been shipmates with Governor Bligh?’

‘I would not say we were shipmates,’ Temeraire put in; he did not care to be saddled with such a relationship. ‘He came aboard our ship, but no-one much wanted him; only one must be polite.’

Laurence looked a bit rueful, and MacArthur, smiling, said, ‘Well, I won’t say anything against the gentleman, only perhaps he was no’ too fond of our ways. The which,’ he added, ‘certainly can be improved upon, Mr. Laurence, I do not deny it; but no man likes to be corrected by come-lately.’

‘When come-lately is sent by the King,’ Laurence said, ‘one may dislike, and yet endure.’

‘Very good sense; but good sense has limits, sir, limits,’ MacArthur said, ‘where it comes up hard against honour: some things a man of courage cannot bear, and damn the consequences.’

Laurence did not say anything; Laurence was quite silent. After a moment, MacArthur added, ‘I do not mean to make you excuses: I have sent my eldest on to England, though I could spare him ill, and he must make my case to their Lordships. But I will tell you, I do not tremble, sir, for fear of the answer; I sleep the night through.’

Temeraire became conscious gradually, while he spoke, of being poked; Emily was at his side, tugging energetically on his wing-tip. ‘Temeraire!’ she hissed up to him, ‘I oughtn’t go right up with that fellow there, he is sure to see I am a girl; but we must tell the captain, there is a ship come from England—’

‘I see her!’ Temeraire answered, looking over into the harbour: a trim, handsome little frigate of perhaps twenty-four guns: she was drawn up not far from the Allegiance, riding easily at anchor. ‘Laurence,’ he said, leaning over, ‘there is a ship come from England, Roland says: it is the Beatrice, I think.’

MacArthur stopped speaking, abruptly. Emily tugged again. ‘That is not the news,’ she said, impatient. ‘Captain Rankin is on it.’

‘Oh! whyever should he have come?’ Temeraire said, his ruff pricking up. ‘Is he a convict?’ Without waiting for an answer, he turned his head to the other side. ‘And Roland says that Rankin is here, on the ship: that dreadful fellow from Loch Laggan. You may certainly put him in a quarry,’ he added to MacArthur. ‘I cannot think of anyone who deserves it more, the way he treated poor Levitas.’

‘Oh, why won’t you listen,’ Roland cried. ‘He ain’t a convict at all; he has come for one of the eggs.’

Chapter Three (#ulink_04e13225-4dad-5815-932c-84309fedda41)

‘Owing to the mode of our last communication, it is quite impossible Mr. Laurence and I should have any intercourse. I hope I may not be thought difficult,’ Rankin said, his crisp and aristocratic vowels carrying quite clearly, over the deck of the Allegiance; his transport the Beatrice had already gone away again, with no more news for the colony: she had left only two months after the Allegiance herself, and the news of the rebellion had not yet reached the Government. ‘But it is generally accepted, I believe, that the dragondeck is reserved for officers of the Corps; and if the gentleman is quartered towards the stern, I see no reason why any inconvenient scenes should arise.’

‘I see no reason why I shouldn’t push his nose in for him,’ Granby said, under his breath, joining Laurence on the leeward side of the quarterdeck, where passengers were ordinarily allowed liberty. ‘The worst of it,’ he added, ‘is I can’t see any way clear to refusing him: the orders are plain black on white, he is to be put to Wringe’s egg. What a damned waste.’

Laurence nodded a little; he, too, had had a letter, if not in an official capacity. ‘… though would I like nothing better than for him to sink on his way to you,’ Jane had written. ’… but his damned Family have been squalling at their Lordships for nigh on Five Years now, and he had the infernal Bad Luck — mine, that is — of finding himself in Scotland, lately, when we were so overset: went up with one of the Ferals out of Arkady’s pack, saw a little fighting, and managed to get himself wounded again.

‘So I must give him a Beast, or at least a Chance of one, and Someone must put up with him thereafter; as I am about to have twenty-six hatchlings to feed and likely enough a War in Spain, I don’t scruple to say, Better You Than Me.’

This last was emphatically full of capitals, and underlined.

‘I have made the Excuse, that this is the first Egg we have had out of the Ferals, and his having Experience of them in the field, should be an Advantage in its Training.

‘I was tolerably transparent, I think, but a Title does wonderful things, Laurence: I should have contrived one much sooner if I had known it’s Use. Gentlemen who swore at me like fishwives sixmonth ago are become sweet as milk, all because the Regent has signed some scrap of paper for me, and nod their Heads and say Yes, Very Good, when before they would have argued to Doomsday if I should say, It is coming on to rain. Also it is a great benefit they none of them know whether to say Milady or Sir, and as soon as they have arrived at a Decision, they change it again. I only hope they may not make me a Duchess to make themselves easy by saying Your Grace; it would not suit half so well.

‘I am very obliged to your Mother, by the bye: she wrote, when she saw my name had come out in Debrett’s — as J. Roland, very discreet — and had me to a nice, sociable little Dinner, with every Cabinet Minister she could contrive to lay hands on: all very shocked, as they had brought their Wives, but they could not say so much as Boo with Her Ladyship at the foot of the Table as if Butter would not Melt in her mouth, and the Ladies did not mind inn the Least, when they understood I was an Officer, and not some Vauxhall Comedienne. I found them sensible Creatures all of them, and I think perhaps I have got quite the wrong Notion about them, as a Class; I expect I ought to be cultivating them. I don’t mind Society half so much if I may wear Trousers, and they were very kind, and left me their Cards.

‘We are trundling along well enough otherwise and getting back into some Order: feeding dragons on Mash and Mutton Stew is a damn’d site cheaper, Thank God, if the older ones do complain; Excidium is all Sighs and loud Reminiscences of fresh Cattle, and Temeraire’s name is not much lov’d among them, for having given us the Technique.

‘I will say a word in your Ear for him: I am uneasy about this Business in Spain. Bonaparte is no’ a Fool, and why he should wreck a dozen cities, on the southern Coast, fresh from the ruin of his Invasion, I cannot understand. Mulgrave thinks he means to take Spain and to stop us from supplying them from the Sea, but for that, he ought to be burning them in Portugal, instead.

‘If Temeraire should think it some Contrivance of Lien, some Chinese Stratagem, I would be glad to know of it, even late as the Intelligence must come: it is very strange to think, Laurence, that I cannot hope for an Answer in less than ten Months and a year and a half the more likely. Now we have lost the Cape Town port to those African fellows, the couriers cannot even go to India, and meet your letter halfway.

‘For Consolation, if you should find yourself overcome with Passion and happen to accidentally drop Rankin down a Cliff, or by some Mischance run him through, at least I will not hear of it for as long, and anyway you are already transported, which I must call a great Convenience for Murder. But I do not mean to Hint, although it is a great Pity to waste an Egg upon him, even one of our poor unwanted Stepchildren.’

The three eggs which had been sent with them to begin the experiment were not, by the lights of Britain’s breeders, any great prizes: one a dirt-common Yellow Reaper, sent over because there were seventeen such eggs in the breeding grounds waiting; the second a disappointing and extremely stunted little thing which had unaccountably been produced out of a Parnassian and a Chequered Nettle, both heavyweights. The last and most promising of the three, large and handsomely mottled and striated, was the offspring of Arkady, the feral leader, and Wringe, the best fighter of his pack.

There was no great enthusiasm for this egg in Britain, where the breeders for the most part viewed the newly recruited ferals as demons sent to wreak havoc and destruction upon their carefully designed lines; so it had been sent away. But it had quickly become the settled thing among the aviators who had been sent along as candidates for the new hatchlings to anticipate great things of the egg. ‘It stands to reason,’ Laurence had overheard more than one officer say to another, ‘if that Wringe one should have got so big out in the wild, this one should do a good deal better with proper feeding, and training; and no one could complain of the ferals’ fighting spirit.’

Those young officers were now in something of a quandary, which Laurence was not above grimly enjoying, a little: they had been firm and united in their disdain, both for his personal treason and for what they saw as his failure to manage Temeraire properly. But now Rankin had come to supplant one of them, and claim the best egg for himself; he was at once their most bitter enemy, and Temeraire’s recalcitrance their best hope of denying him.

‘He mayn’t have it at all,’ Temeraire had said at once, when he had been informed of the proposed arrangement, ‘and if he likes, he can come up here and try and take it; I should be very pleased to discuss it with him,’ darkly, in a way which bade fair to answer all of Jane’s hopes.

‘My dear,’ Laurence said, having lowered his letter, ‘I like the prospect as little as you; but if he should be denied even the chance, and return to England thwarted, we have only deferred the evil: he will certainly be put to another egg, there, where you may be certain the poor hatchling will have less opportunity to refuse. And the blame will certainly devolve upon Granby: the orders are for him, and the responsibility to carry them out.’

‘I am certainly not having Granby take the blame for anything,’ Iskierka said, raising her head, ‘and I do not see what the problem is, anyway; the egg will be hatched, by then, and why should it be any business of ours what it does after that? It can take him or not, as it pleases.’

Iskierka herself had hatched already breathing fire, and with all the disobliging and determined character anyone could have imagined; she would certainly have had no difficulty in rejecting any unworthy candidate. Most hatchlings did not come from the shell with quite the same mettle, however, and the Aerial Corps had developed many a technique and lure to ensure the successful harnessing of the beasts. Rankin had certainly prepared himself well: he had come over from the Beatrice with not only his two chests of personal baggage, but a pile of leather harness, some chain-mail netting, and a sort of heavy leather hood.

‘You throw it over the hatchling’s head as it comes out of the shell, if you are out-of-doors,’ Granby said, when Laurence now inquired, ‘and then it cannot fly away; when you take it off, the light dazzles their eyes, and then if you lay some meat in front of them, they are pretty sure to let you put the harness on, if you will only let them eat. And some fellows like it, because they say it makes them easier to handle; if you ask me,’ he added, bitterly, ‘all it makes them is shy: they are never certain of their ground, after.’

‘I wonder if you might be able to put me in the way of some cattle merchant,’ Rankin was saying, to Riley and Lord Purbeck. ‘I intend to provide for the hatchling’s first meal from my personal funds.’

‘Surely he can be restrained in some way,’ Laurence said, low. He was not yet beyond the heat of righteous anger kindled all those years before, when they had been unwilling witness to the cruelty of Rankin’s treatment of his first dragon. Rankin was the sort of aviator beloved of the Navy Board: in his estimation as in theirs, dragons were merely a resource and a dangerous one, to be managed and restrained and used to their limits; it was the same philosophy which had rendered it not only tolerable but desirable to contemplate destroying ten thousand of them through the underhanded sneaking method of infection.

Where Rankin might have been kind to Levitas, he had been indifferent; where indifferent, deliberately cruel, all in the name of keeping his poor beast so downtrodden as to have no spirit to object to any demands made upon it. When Levitas had with desperate courage brought them back the warning of Napoleon’s first attempt to cross the Channel, in the year five, and been mortally wounded in that effort, Rankin had left his dragon alone and slowly dying in a small and miserable clearing, while he sought comfort for his own lesser injuries.

It was a mode of service which had gone thoroughly out of fashion in the last century among most aviators, who increasingly preferred to better preserve the spirit of their partners; the Government did not always agree, however, and Rankin was of an ancient dragon-keeping family, who had preserved their own habits and methods and passed these along to the scions sent into the Corps, at an age sufficiently delayed for these to be impressed upon them firmly, along with a conviction of their own superiority to the general run of aviators.

‘He cannot be permitted to ruin the creature,’ Laurence said. ‘We might at least bar him from use of the hood—’

‘Interfere with a hatching?’ Granby cried, looking at Laurence sidelong and dismayed. ‘No: he has a right to make the best go of it he can, however he likes. Though if he can’t manage it in fifteen minutes, someone else can have a try,’ he added, an attempt at consolation, ‘and you may be sure fifteen minutes is all the time he will have; that is all I can do.’

‘That is not all that I can do,’ Temeraire said, mantling, ‘and I am not going to sit about letting him throw nets and chains and hoods on the hatchling: I do not care if it is not in the shell anymore. In my opinion, it is still quite near being an egg.’