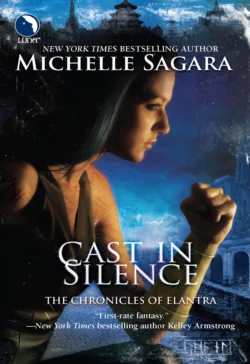

Cast in Silence

Michelle Sagara

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 612.81 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: Don′t ask. Don′t tell. Stay alive.A member of the elite Hawk force that protects the City of Elantra, Kaylin Neya has sacrificed much to earn the respect of the winged Aerians and immortal Barrani she works alongside. But the mean streets she escaped as a child aren′t the ones she′s vowed to give her life guarding. Those were much darker…Kaylin′s moved on with her life… and is keeping silent about the shameful things she′s done to stay alive. But when the city′s oracles warn of brewing unrest in the outer fiefdoms, a mysterious visitor from Kaylin′s past casts her under a cloud of suspicion. Thankfully, if she′s anything, she′s a survivor…