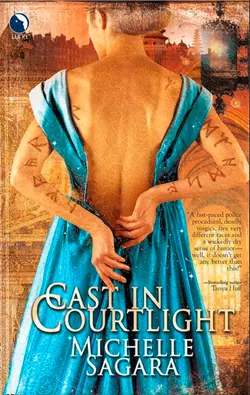

Cast In Courtlight

Michelle Sagara

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Зарубежное фэнтези

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 305.03 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: In Elantra, a job well done is rewarded with a more dangerous task.So after defeating a dark evil, Kaylin Neya goes before the Barrani High Court, where a misspoken word brings sure death. Kaylin’s never been known for her grace or manners, but the High Lord’s heir is suspiciously ill, and Kaylin’s healing magic is the only shot at saving him—if she can dodge the traps laid for her. …“Readers will embrace this compelling, strong-willed heroine. ”—Publishers Weekly