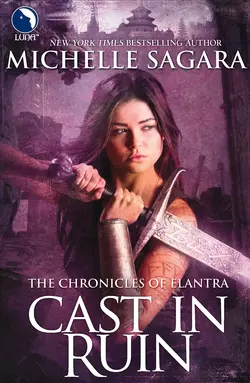

Cast in Ruin

Michelle Sagara

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Зарубежное фэнтези

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 612.81 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: Seven corpses are discovered in the streets of a Dragon′s fief. All identical, down to their clothing. Kaylin Neya is assigned to discover who they were, who killed them – and why.Is the evil lurking at the borders of Elantra preparing to cross over?At least the investigation delays her meeting of the Dragon Emperor. And as the shadows grow longer over the fiefs, Kaylin must use every skill she′s ever learned to save the people she′s sworn to protect.Sword in hand, dragons in the sky, this time there′s no retreat and no surrender…