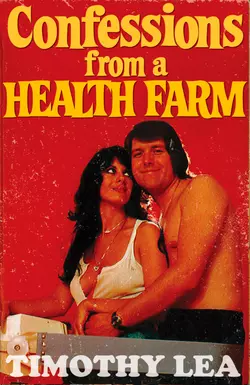

Confessions from a Health Farm

Confessions from a Health Farm

Timothy Lea

It’s your duty to be beautiful…Another exclusive ebook reissue of the bestselling 70s sex comedy series.Bosky Dell Health Spa – relaxing, bracing – and absolutely full of women…Mrs Chalfont doesn’t seem at all tired by the early mornings and modest breakfasts, though – and she seems to want to work off her excess energy with Timmy and Sid…Also Available in the Confessions… series:CONFESSIONS OF A WINDOW CLEANERCONFESSIONS OF A LONG DISTANCE LORRY DRIVERCONFESSIONS OF A TRAVELLING SALESMANand many more!

Confessions from a Health Farm

BY TIMOTHY LEA

Contents

Title Page (#u1e9eb89f-7e0b-56e3-87af-09921a8ea1e1)

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Also available in the CONFESSIONS series

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Also by Timothy Lea & Rosie Dixon

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher

CHAPTER 1 (#u2e95039a-49e6-57c7-a8bd-d67379a60aa1)

‘I got a post card from Nutter, today,’ says Sid, pushing away his tea cup as if he never wanted to see one again – with Mum’s tea you feel like that.

‘That’s nice. How is he?’ I say.

‘Difficult to tell. Most of it has been crossed out by the censors. He seems a bit under the weather, though – not surprising when you think how much it rains over there.’ Sid laughs heartlessly.

I pick up the postcard: ‘The paddy fields, Ho-lung-ti.’

‘It looks nice, doesn’t it,’ I say. ‘The mountains and all that in the background.’

‘Blooming marvellous,’ says Sid. ‘I envy those boys, really I do. Doing away with National Service was the worst thing we ever did in this country. I remember how disappointed I was when they stopped it just before I was due to be called up.’

‘Why didn’t you sign on, then?’

Sid looks uncomfortable. ‘It wouldn’t have been the same, would it? I mean, I wanted to go in with all my mates, didn’t I?’

‘They could have signed on as well, Sid.’

Sid shakes his head. ‘Not everybody feels the same as I do about this septic isle, Timmo. I’ve only got to hear the opening bars of Land Of Hope And Glory and I’m rummaging through Rosie’s Kleenex.’

I tear my mind away from this affecting thought and examine the postcard. The first word is scratched out and followed by ‘you’ and an exclamation mark. Then comes another ‘you’ followed by three words that have been crossed out followed by a double exclamation mark. Fortunately, though it would have been unfortunately, had I been of a sensitive disposition, I can still read one of the crossed-out words.

‘I don’t reckon it was the blokes in Taiwan that censored this, Sid,’ I say. ‘It must have been our lot. Nutter isn’t half having a go at you.’

Not that I blame the poor sod. If you read Confessions of a Pop Star you will recall that Nutter and a group called ‘Kipper’ were rail-roaded out to Taiwan, that used to be Formosa like Alvin Stardust used to be Shane Fenton, by Sidney Noggett who still is my brother-in-law. They thought they were going to promote their chart-busting record but Sidney had arranged for them to promote the Taiwanese war effort by signing them on for five years in Chiang Kai-Shek’s army. Sidney does not usually go to this amount of trouble for people unless they are costing him money and there is little doubt that ‘Kipper’ were becoming an expensive luxury.

Sid picks up the postcard. ‘It’s a nice stamp, though, isn’t it? I’ll save that for little Jason.’

‘You never think about them, do you?’ I accuse. ‘Thousands of miles from home and with none of their own kind near them.’

‘They never have any of their own kind near them,’ says Sid, bitterly. ‘You tell me one person who is as greedy, lazy and useless as they are.’

‘I don’t want to hurt your feelings, Sid,’ I say after I have thought about it for a minute.

Sidney waggles his finger at me. ‘That’s very naughty, Timmo. You know how sensitive I am.’

I take a long look at the poor little suffering tea leaves at the bottom of my cup and decide to change the subject. ‘What’s this new idea of yours, Sid?’ I ask.

‘It’s a gold mine,’ says Sid.

My heart sinks. I can just see it. Some clapped out National Coal Board reject that Sid has been conned into buying. Broken down lifts, flooded galleries, no pit head baths, worked out seams. And who will end up thousands of feet below the earth with a Mickey Mouse torch tied to his bonce and a kiddy’s spade in his mitt? That’s right, yours bleeding truly.

‘I’m sorry, Sid,’ I say. ‘I don’t want any part of it.’

‘But you haven’t heard what it is yet!’

‘I don’t care about the details. I’m not going down any mine.’

Sidney claws the air in exasperation. ‘I was talking metaphysically, wasn’t I? I don’t mean a real gold mine. I never fancied mines after I saw Shaft.’

‘Shaft wasn’t about mining, Sid.’

‘You mean that big, black bloke didn’t have coal dust all over his mug?’

‘No, Sid! He was born like that.’ Honestly, you worry sometimes, don’t you? They say that there are over a million illiterates in the country and I reckon that they lie pretty thick around Scraggs Lane.

‘Oh,’ says Sid. ‘That explains a lot of things.’

‘What about the new idea?’ I say.

Saying that to Sid is like striking a match to find a gas leak, but somehow I can’t help myself. I have been stuck with Sid for so long that I cannot break away. Like a junkie begging for his fix I must know what half-baked scheme the Maestro of Muddle has come up with now.

Sidney leans back nonchalantly and rests his elbow in the frying pan that Mum has left on top of the cooker. Like everything on the cooker, including the rings, it is coated in half an inch of grease and is well equipped to become the first item of hardware to swim the Channel. Sid’s safari jacket therefore has to make a quick trip into the interior of the washing machine before the great white hunter can continue.

‘Do you know what is the biggest problem facing this country today?’ says Sid.

‘Inflation?’ I say. I mean, I listen to the party political broadcasts, don’t I? There is no bleeding alternative.

‘In a manner of speaking,’ says Sid, slightly downcast. ‘Obesity was the word I had in mind.’

Well, it is a free country, isn’t it? I can’t tell him what words to put in his mind, although they would have to be blooming small to fit into that tiny little space. I would have thought that you needed to fold ‘obesity’ in half to get it in without touching the sides.

‘Oh yes,’ I say.

‘You don’t know what obesity means, do you?’ says Sid, triumphantly.

‘No,’ I say. ‘That’s why you used it, isn’t it?’

‘It means being fat.’ Sidney looks me up and down critically. ‘About ninety percent of the people in this country weigh too much.’

‘That’s amazing,’ I say, stretching out my hand for another doughnut.

‘You for instance,’ says Sid. ‘It’s disgusting to see a bloke of your age falling apart at the seams.’

‘What are you rabbiting on about?’ I say. ‘I’m in perfect physical condition. I could run rings round you any day of the week.’

‘You must have put on a stone since you came out of the army,’ continues Sid. ‘You’ve got the beginnings of a paunch and there are rolls of fat building up round your waist. I can’t imagine how you do it. Living here I’d have thought that you had a bloody marvellous incentive not to eat.’

Sid is, of course, referring to Mum’s cooking. He has never had any time for her since she tried to boil a tin of sardines. Mind you, she is diabolical in the kitchen and maybe that is why I eat so much. I am forced to have a go at the nosh she dishes up and I also eat between meals to take away the taste and give myself a little reward.

‘You’re no oil painting,’ I say.

‘I’m fitter than you are, mate. Feel that.’

‘Sidney, please!’

‘I meant my stomach, didn’t I? Don’t take the piss.’

‘I don’t want to feel your stomach, Sid.’

‘Go on!’ Sid is speaking through clenched teeth as he tenses his muscles. Reluctantly, I stretch out a hand.

‘It feels like a pregnant moggy,’ I say.

Sid does not respond well to this suggestion. ‘Bollocks!’ he says. ‘Like ribs of steel, my stomach muscles. You try hitting them.’

‘Sidney, please! This is bloody stupid.’

‘Hard as you like. Go on!’ Sidney stands up and swells out his belly invitingly.

‘I don’t want to hurt you, Sid,’ I say.

‘You can’t hurt me! That’s what I’m trying to tell you, you berk! I’m in shape, I’m fit, I’m – uuuuuurgh!’

I give him a little tap in the stomach and he collapses on the floor, spluttering and groaning. Mum comes in.

‘He hasn’t been at the bread and butter pudding, has he?’ she says, alarmed.

‘No, Mum.’

‘Thank goodness for that. You were right, you know. Some of those sultanas were blue bottles. I think I’ll have to throw it away. It’s such a fiddling job picking them all out.’ She looks down at Sid. ‘What’s the matter with him?’

‘He was showing me how fit he is,’ I say.

‘He hit me when I wasn’t ready,’ wheezes Sid. ‘That’s what happened to Houdini.’

‘Oh dear,’ says Mum. ‘That doesn’t sound very nice. I wouldn’t stay down there if I was you. It’s not very clean.’

Sid drags himself to his feet and slumps into a chair. Mum was right. He looks like the inside of a carpet sweeper.

‘You did that on purpose,’ he grunts.

‘Of course I did,’ I say. ‘You told me to.’

‘You haven’t put anything in the washing machine, have you?’ says Mum.

I sense Sid stiffen. ‘What’s wrong with it?’ he says.

‘I don’t know,’ says Mum. ‘The man hasn’t been yet. I think it spins round too fast. Either that or there is a rough edge in there.’

Sid springs to the machine and presses the programme switch. He wrenches open the door and a couple of gallons of water thwack against the far wall.

‘I didn’t notice that was in there,’ I say. I am referring to the well-worn chammy leather with pockets.

Sid groans. ‘Eighteen quid that cost.’

‘Blimey! That’s your safari jacket, isn’t it?’ I say.

‘Don’t sound so bleeding cheerful,’ snarls Sid. ‘You ought to have put an “out of order” sign on it.’

‘I did,’ says Mum. ‘But I moved it to the bread and butter pudding.’

‘Gordon Bennett!’ Sid covers his face with his hands.

‘Sid has got a new idea,’ I say, deciding that it is time for another change of subject. ‘It’s something to do with fat people.’

‘I’m going to classes now,’ says Mum. ‘Do you think I look any different?’

‘You look a bit paler, Mum,’ I say.

‘Don’t say that! I was thinking how well I looked. I’ve lost half a stone, you know.’

‘Where did you lose it, Mum?’ I ask.

‘Round the bum, mostly,’ says Mum, with an honesty I could have done without.

‘I didn’t mean that,’ I say hurriedly before she can impart any more revelations. It’s not nice listening to your parents talk about their bodies, is it? It is bad enough having to look at them.

‘The Lady Beautiful Health Clinic,’ says Sid. ‘That’s what I’m on about. More and more people are becoming worried about the condition of their bodies. You mother is only following a trend.’

‘You want to be careful, Mum,’ I say. ‘You remember what happened when you tried that yoga.’ I have to suppress a shudder when I think about it. Everywhere you went in the house there would be Mum standing on her head against one of the walls. And often without any clothes on! Yoga Bare, that’s what Sid used to call her. Luckily she bombed out in the Padandgushtasana position and we did not hear any more about it.

Further discussion is interrupted by the sound of the front door bell.

‘Who’s that?’ says Sid whose reaction to the unexpected reveals a permanently guilty conscience.

‘Probably Dad’s lost his front door key,’ says Mum. She leaves the kitchen and pads off to have a peep through the front room curtains. A couple of minutes later she returns.

‘There’s a gorilla standing on the front door step,’ she says.

‘A stuffed one? With Dad?’ says Sid.

‘No, it’s carrying a briefcase,’ says Mum.

‘Probably something to do with one of those soap powder promotions. Have you got a packet of Tide in the house?’

‘No!’ says Mum, getting all agitated. ‘You keep him talking while I nip out and get one.’

I grab hold of her just before she disappears out of the back door.

‘Hold on, Mum. We don’t know it’s Tide. It could be any of them. You don’t want to spend a fortune for nothing.’

There is another long blast on the front door bell followed by frenzied banging.

‘Sounds like your father,’ says Mum.

‘Let’s have a look.’ I follow Sid into the front room and peel back the yellowing net curtains. There, indeed, is a gorilla carrying a briefcase. It looks towards the window and jabs its finger at its stomach.

‘I think it’s trying to say it’s hungry,’ I say.

‘No, you berk. It’s trying to say its zipper has jammed. Don’t you recognise your own father? He looks more like himself in that than he does in a suit. No gorilla ever stands like that.’ A small crowd of onlookers has assembled at the gate and the gorilla makes a familiar gesture to them.

‘Yes, that’s Dad all right,’ I say. ‘I suppose we’d better let him in.’

‘About bleeding time!’ says Dad’s muffled voice as he charges through the door. ‘A man could suffocate in one of these things.’

‘Now he tells us,’ says Sid. ‘Another couple of minutes on the doorstep and all our troubles would have been over.’

‘Belt up, sponger!’ croaks Dad. ‘Help us get it off, for gawd’s sake!’

We struggle with the zip and eventually manage to release an escape hatch for Dad.

‘Phew!’ says Sid. ‘Are you sure the gorilla isn’t still in there with you? It doesn’t half pong around here.’

‘That’s the bloody tube for you,’ says Dad. ‘You want to try strap hanging from Charing Cross in that thing and see how you feel.’

‘Did you swing from strap to strap, Dad?’ asks Sid, lowering his voice and beating his chest. ‘Me, father Lea. King of de Northern Line.’

‘Shut your face!’ snaps Dad. ‘It’s a lovely thing. I couldn’t let it go in the incinerator.’

I feel I should point out that my revered parent works in the lost property office and is inclined to ‘save’ certain articles which he considers might be lost to Sir Kenneth Clark, or handed in to the keeping of undesirables – e.g. their rightful owners.

‘I don’t understand why you wore it,’ says Mum.

‘It seemed the best way of getting it home,’ says Dad, mopping his brow. ‘I’d have looked bloody silly carrying it, wouldn’t I? This way I was anonymous so nobody knew who I was. The coon who was collecting the tickets at Clapham South took one look at me and started running across the common.’

‘I bet you weren’t even wearing the head-piece, then,’ I say cheerfully.

‘At least he could run,’ says Sid. ‘Look at you. Puffing and blowing like an old grampus. You underline what I’ve been saying to Timmy and Mum. You’re all overweight and unfit. The whole country is dragging round tons of surplus weight. That’s why we’re in the mess we are at the moment. Pare off those extra pounds and the natural vitality will start flooding through your veins.’

‘Sounds disgusting,’ says Dad. ‘Is my tea ready yet?’

‘You’re the worst of the lot,’ says Sid sternly. ‘There’s a permanent depression in the middle of the armchair made by your great fat arse while you watch telly. The only exercise you ever take is jumping to conclusions.’

‘How dare you!’ bellows Dad. ‘This is my house you’re standing in. You keep your filthy tongue under control. I don’t have to listen to this.’

‘Look at him!’ says Sid. ‘That’s a sick face, that is, mark my words. See those treacherous little blue veins running through that sea of scarlet porridge? That’s not healthy. That’s a face living on borrowed time.’

‘He doesn’t look very good, does he?’ says Mum, peering into Dad’s mug. ‘Still, you’ve got to remember he’s been like that for years.’

‘Stop talking about me as if I’m not here!’ squawks Dad.

‘That’s it exactly,’ says Sid. ‘Very prophetic words. Soon you won’t be here. You’ve got to get a grip on yourself. Like I said, you’re living on borrowed time.’

‘If you ever lend me any, you won’t see it back again in a hurry,’ says Dad bitterly.

‘What are you getting at, Sid?’ I say. ‘Are you starting some kind of keep-fit class?’

Sidney’s lip curls contemptuously. ‘Much more than that,’ he says. ‘Keeping fit is just the tip of the iceberg. It’s the whole spectrum of physical and mental welfare that I want to embrace.’

‘Watch your language in front of my wife,’ says Dad.

Something tells me that Sid has been got at. He does not normally come out with sentences like that unless his chips were wrapped in the Weekend section of the Sunday Times.

‘Who told you about that?’ I ask.

‘Wanda Zonker,’ says Sid as if he is glad to get it off his chest. ‘She’s a remarkable woman. She’s a beautician and health food specialist. I’m thinking of getting together with her to open a health farm.’

‘Where’s the money coming from?’ says Dad.

‘I’ve got a bit tucked away,’ says Sid.

‘So you’ve just told us,’ says Dad. ‘I was asking about the money.’

Sid does not take kindly to the implication behind this remark.

‘Shut your mouth, you disgusting old rat bag!’ he snaps. ‘Rosie will probably be coming in with us. There’s nothing underhand about what I’m doing. Nothing compared to nicking stuff from the lost property office and keeping the hall stand full of filthy Swedish magazines.’

‘How did you know they were Swedish, clever shanks!?’ exults Dad. ‘You’ve been peeping, haven’t you?’

‘Please!’ I say, desperate to raise the standard of argument a few notches above crutch level. ‘Can’t we forget about “Swedish Spanking Party, Volumes 1–5” and concentrate on something more intellectually stimulating?’

‘You were at them and all, were you?’ says Dad. ‘Marvellous, isn’t it? I only bring them home for the articles and I’m being branded as some kind of pervert.’

‘What articles?’ says Sid. ‘“How spanking saved my marriage”? “Spanking round the world”? “Cooking for spankers”?’

‘Nothing like that!’ snorts Dad. ‘I mean the articles by famous living men of letters. I don’t look at the pictures.’

‘Yeah. Smoke rises from his fingers, he turns the pages over so fast,’ sneers Sid.

‘ “Wanda Zonker”?’ says Mum. ‘She foreign, is she?’ There is a strong note of disapproval in her voice. Mum has been around long enough to know that foreigners cause most of the trouble in the world.

‘Yes, Mum. She’s a Lithuanian.’

‘Oh.’ Mum does not sound as if that is the best news she has heard since the end of World War Two. ‘Where’s that?’

Sid looks round the room and shrugs his shoulders. ‘I don’t know, Mum.’

‘I’ve never met anyone who did know,’ says Mum suspiciously. ‘You want to watch those Lithuanians. There’s a lot of them about and nobody knows where they come from. You want to ask her if you see her again.’

‘If she says Peckham, he’s not going to know whether she’s telling the truth or not,’ says Dad.

‘It’s definitely abroad,’ says Mum.

‘ “Next week, our panel of experts will be discussing Euthanasia – does it come too late?” ’ says Sid in his posh announcer voice. ‘Come on, Timmo. I’ll go bonkers if I hang around here much longer. I’m nipping round to see Wanda now. I’ll introduce you.’

‘You watch yourself,’ says Dad. ‘Don’t sign anything.’

‘Tell you what I’ll do,’ says Sid. ‘When it’s all fixed up I’ll give you a fortnight’s free treatment. That’ll open your eyes – your pores, your bowels, everything!’

‘Don’t be disgusting!’ Dad’s voice echoes after us as we bundle out of the front door.

Sid rubs his hands together and a faraway look comes into his eyes. ‘Ooh. I wouldn’t half like to get him in one of those dry heat cabinets,’ he says. ‘I’d turn the bleeding knob up to maximum and watch his nut turn scarlet. Twenty minutes later there would be nothing left but a puddle in the bottom of the cabinet.’

‘Sid! Please! That’s my old man you’re talking about.’

Sid shakes his head. ‘I’m sorry. I keep forgetting that he’s a human being.’ Sid has been bashing the horror movies a bit lately and I think that they have an unfortunate effect on him. He is always knocking back his char with a maniacal laugh and saying, ‘Today, Clapham. Tomorrow the world!’ I could belt him sometimes.

‘Where does this tart live?’ I ask.

An expression of pain flashes across Sid’s features. ‘Watch it,’ he says. ‘She’s quality, this bird. Refined. You know what I mean?’

‘She washes her hands before she goes to the karsi?’

Sid shakes his head. ‘Don’t take the piss, Timmo. She’s living in reduced circumstances at the moment but she’s still a lady.’

‘How did you meet her?’ I ask.

‘Down the whelk stall in Northcote Road.’

‘Oh yes. Very salubrious,’ I say. ‘Washing them down with a glass of bubbly, was she?’

‘Whelks happen to be one of the great health foods,’ says Sidney loftily. ‘You wouldn’t cocoa some of the things whelks can do for you.’

‘I know what they do for me,’ I say. ‘And when you see them they look as if they’ve already done it.’

‘Gordon Bennett! You’re disgusting, you are. You take after your old man, there’s no doubt about it.’

‘Leaving the whelks to one side,’ I say. ‘What is this bird doing at the moment?’

‘She’s practising her craft,’ says Sid. ‘She’s a fully qualified masseuse as well as all the other things. She’s got a string of initials after her name long enough to spell out your moniker.’

All the time we are rabbiting, Sid is pushing the Rover 2000 towards Battersea Park and the river – I don’t mean literally, though with the price of petrol what it is today you could be excused for wondering.

‘I think it’s very nice round here,’ I say. ‘All those trees and the kids digging up the snowdrops.’

‘Oh it is,’ says Sid. ‘But it’s not what she’s used to. Back in Druskininkai, things were different.’

‘I imagine they would be,’ I say, philosophically.

‘Here we are.’ Sid stops outside a block of flats facing the park and we get out. The column of bell pushes looks like the buttons on a giant’s waistcoat but the front door is open and Sid sweeps over the threshold and heads for the stairs. It is funny, but I have never visited anybody in a block of flats who did not live either in the basement or right at the bleeding top. Sometimes I think that the floors in between are used for storing old furniture. There is never any sign of life on them. Not so the top floor of Porchester Mansions. The whole place is vibrating and the squeaking skylight sets your teeth on edge, the noise it is making.

‘She must have a client,’ says Sid.

‘If she does embalming she could have another one,’ I pant. ‘Blimey, those stairs don’t half knacker you.’

‘Because you’re so bleeding unfit,’ says Sid contemptuously. ‘Look at me, I’m hardly out of breath. It’s all a question of diet and a few exercises.’

I take a quick shufti at Clapham’s answer to Paul Newman and I have to confess that he does not look in bad nick. Maybe Madam Zonker knows a thing or two.

Just as that moment there is a long drawn out moan that quite puts the mockers on me. I am not surprised that the pigeon which has landed on the skylight relieves itself. I feel a bit edgy myself.

‘What’s that?’ I say.

‘Dunno,’ says Sid. ‘She seems to have finished anyway.’

The shuddering and shaking has certainly stopped and no sooner has Sid stepped towards the door than it swings open. Revealed to my hungry mince pies is a handsome looking bird wearing a cross between a housecoat and a judo robe. She has short hair and sharp, determined features.

‘Hello, Sidney sweetie,’ she says. ‘You have not seen the milkman, have you? He gets later every day. Henry wants his Ovaltine.’ Her accent is very good but you can tell that she is not British. She leans forward to look down the stairs and I can see that her knockers would make a lovely pair of bookends if you could think of the right item to put between them.

‘I haven’t,’ says Sid. ‘Wanda, I’d like to introduce my brother-in-law, Timothy Lea. He’s very interested in physical culture, though you might not believe it to look at him.’

‘Charmed,’ I say.

Wanda smiles and I notice that she has a few gold teeth sprinkled around her cakehole. ‘Likewise,’ she says. ‘Come in. My session with Sir Henry is over.’ She raises the voice when she says the last bit and I get the impression that she is giving someone a message.

I look over her shoulder and there is an elderly geezer adjusting his tie in front of the mirror.

‘Your shirt’s hanging out at the back,’ I say helpfully.

The bloke turns round and – blimey! I recognise that face. I saw him on Midweek. Not for long though, because I was looking for the wrestling. Maybe it was the wrestling? No, it couldn’t have been. Some of them look a bit past it but not as far gone as this geezer. He could rupture himself climbing through the ropes.

‘Thank you,’ he says, looking very uncomfortable.

‘I always find that’s happened when I’ve been to the karsi,’ I say, trying to put him at his ease.

‘Karsi?’ says the bloke.

‘Bog, shit-house,’ I say, helpfully. ‘I always feel a bit of a berk when somebody points it out.’

Who is he? I know I’ve seen him. If he was on the telly after ten o’clock he must be a politician. Oh yes, that’s right! He’s the minister for something. If I can get his autograph I will know who he is. Mum will be impressed, too. He is wearing a waistcoat so he must be a Conservative. Mum has a secret hankering for them. I am quite partial myself. I mean, they have all the money, don’t they?

‘I am afraid that there is no Ovaltine, today,’ says Wanda, picking up a black mask from the carpet.

‘I must have a word with you,’ murmurs the man.

‘Call me later.’ Wanda plucks a piece of fluff from the man’s suit.

‘I’ve got to have those negatives!’

He sounds really worked up about it. Looking at him, I reckon that he must be one of Miss Zonker’s newer clients. There is little physical evidence that she has taken him in hand. He looks far too slack and flabby.

‘Can I have your autograph?’ I say in what is intended to be my friendly voice.

‘On a blank cheque, I suppose?!’ snaps Sir Henry.

‘Thatll do if you haven’t got a piece of paper,’ I say. ‘Hold on a minute. You can use the back of –’

I break off when I see what I have picked up. It is a photograph of a man on a bed with two girls, one of whom definitely hails from dusky climes, as they say. Both ladies seem to be on very good terms with the gentleman in question and a good time is being had by all. It is not the photograph I would have chosen for my Christmas card to the Archbishop of Canterbury but I can see that it might have a fairly broad appeal to some sections of the market.

Sir Henry blushes, as well he might. ‘I’d hardly have recognised you from that angle,’ I say.

‘You should see some of the others,’ says Wanda. ‘Who knows? Perhaps you will.’

‘Wanda –!’

Sir Henry follows our hostess to the door and I hear his voice continuing to plead with her.

‘Minister of Defence!’ I say.

‘Not any more,’ says Sidney. ‘They swop around so much these days, I lose track.’

‘He didn’t give me his autograph, did he?’ I say. ‘Mum will be disappointed.’

‘Don’t worry. Wanda will get it for you later,’ says Sid. ‘You can have the whole cabinet if you want them.’

‘They’re all physical fitness fanatics, are they?’ I splutter. ‘You wouldn’t think it to look at them.’

‘Half an hour with Wanda makes new men of them,’ says Sid. ‘That’s why I want to set her up somewhere. She’s got the technique and she’s got the contacts. She can’t cope with the demand here.’

‘I think he’s beginning to see the light,’ says Wanda coming in to the room and opening the top drawer of a filing cabinet. ‘Drink, anyone?’ She looks me up and down and darts her tongue between her lips. ‘We’ll have to whittle a few pounds off you, won’t we?’

‘Why?’ I say.

‘Because if you are going to be one of our hygienists you must be seen to be practising what you preach. Your body is the best advertisement for Inches Limited.’

‘That’s the name of the firm,’ says Sid. ‘Clever, isn’t it? We’re negotiating with Sir Henry for the use of his country seat, Long Hall.’

‘Shortly to be renamed Beauty Manor. It’s a residential course, you see?’

‘Sort of,’ I say. They are going a bit fast for me.

Wanda gives Sid a meaningful glance. ‘I think you had better leave us, Sidney sweetie. I want to show Timmy my credentials and give him a few tests.’

‘Oh yes?’ I clear my throat noisily.

‘All right,’ says Sid. ‘Have you got any films to be developed?’

‘Yes,’ says Wanda. ‘And this time, don’t take them to Boots. The address is on the label.’

‘Oh yes,’ says Sid, blushing. ‘I got some very old-fashioned looks when I went to collect them. Fancy dressing up a policeman in a wig. If I hadn’t seen his hobnail boots sticking out from underneath the perfume counter –’

‘Yes, yes. Very distressing,’ says Miss Zonker, waving Sid towards the door. ‘It will teach you to be more careful next time.’

Sid nods at me. ‘See you later, Timmo.’

‘Tra la, Sid.’

The door closes on my brother-in-law and Wanda Zonker subjects me to her penetrating gaze. ‘I’m sorry,’ she says. ‘But I have to scrutinise you.’

Hello! I might have guessed there would be a catch in it. Sidney never said anything about that.

‘You look alarmed,’ says Miss Z.

‘It’s what you were talking about,’ I say. ‘I don’t fancy it. I might want to have children one day and I’ve heard there’s no going back.’

Miss Zonker looks puzzled. ‘Your meaning escapes me,’ she says. ‘Perhaps I had better set your mind at rest by revealing some of my parts’ – in fact she says ‘past’ but she gives me a nasty turn for a moment. ‘I have studied in all the great salons of Europe: Lausanne, Madrid, Stockholm, Paris, Budleigh Salterton. Physical dancing, rhythmical massage, remedial culture, or any combination of the three. I am a founder member of the Volcanic Mud Institute and the Wax Lyrical and have received diplomas from the Papuan Cosmetologists Institute, the Greek National Electrolysis Society and the CBI.’

‘That’s amazing,’ I say. ‘It’s practically a science, isn’t it?’

Miss Zonker’s face clouds over. ‘What do you mean “practically”? We are scientists fighting the war against physical imperfection.’

‘But you don’t have any medical qualifications, do you?’

‘Medical qualifications?’ Miss Z practically holds the words at arm’s length with one hand while applying contractual pressure to her hooter with the other. ‘Our field of activity is so enormous as to defy restriction. There is no part of the mental or physical process that I will not grapple with.’ Her breasts heave when she says it and her eyes blaze. I can see that I have touched on something she feels strongly about. ‘Before we go any further there is one question that I must ask you.’

‘My cards are stamped up to date,’ I say.

‘Are you frightened of the human body?’

This was not the question I was expecting but it is still pretty easy. ‘No,’ I say.

‘Good.’ Miss Zonker suddenly unties the sash of her robe and – eek! She has shed her threads before you can say Roger Carpenter. ‘It’s only flesh, isn’t it? Shoulders, breasts, hips –’

‘Yes!’ I gulp. ‘But –’

‘Nothing to be ashamed of. We’re all the same underneath these dust sheets we call clothes. Take your trousers off.’

Oh dear. I never feel at my happiest when I am up against one of these forward ladies – especially when they come from somewhere in Eastern Europe. You never know what they’ve been used to, do you?

‘Is that really necessary?’ I say.

‘If you reveal signs of an inhibited nature you will be no good to us at Beauty Manor. Think of yourself as a sculptor and human flesh as your clay.’

I try to think about it but I find it difficult. Maybe it is because Miss Zonker is wrestling with my zipper. My, but she is a strong girl. She grits her teeth and – wheeeeeeeeeeh! The opening at the front of my trousers now goes down to my knee.

‘So sorry,’ she says. ‘Now you will have to take them off.’

‘They’re not even split down the seam,’ I say miserably. ‘I’ve only had them a couple of weeks. They were French.’

Miss Zonker removes a screen and starts fiddling with a large stills camera. ‘At Beauty Manor you will wear a toga,’ she says. ‘Right. Just a couple of snaps for the album. We intend to keep a case history of each of our employees. Perhaps you wouldn’t mind posing with that discus.’

‘Sidney didn’t discus this with me,’ I say, wittily. Miss Zonker does not say anything. I expect that, being foreign, she finds it difficult to understand our British sense of humour. ‘How’s this for the pose?’ I say.

‘Very nice,’ she says. ‘But I think it would be better if you took the discus out of your mouth. You look like one of those African women with a plate lip.’

‘Just trying to make it more interesting,’ I say. ‘How about this?’

‘That’s much better. There’s only one thing. It loses a lot with you standing there in your shirt and underpants. The socks don’t help a lot, either.’

‘I don’t like them much, myself,’ I say. ‘My gran gave them to me. You know what it’s like?’

‘Take everything off,’ says Miss Z firmly. ‘I want you naked.’ She starts clicking on spot lights and I have to shield my eyes against the dazzle. ‘Come on.’ I respond to the tone of brisk efficiency in her voice and start sliding down my Y-fronts. After all, she is a professional, isn’t she? If she has cabinet ministers on her books, she must be above suspicion. Funny about that photograph, though. I must talk to her about that.

‘Shove it up by your ear,’ she says.

‘I beg your pardon?’

‘The discus.’

Oh. For a moment I thought we were on to the remedial contortions.

‘This is just for the record, is it?’ I say.

‘That’s right. Bend your knee a bit. That’s lovely. Of course, we might get a cover shot out of it.’

‘A cover shot?’

‘ “Butch Male on the Rampage”, “Health and Dexterity”, something like that.’

‘But I’m not like that!’ I squeak. It’s funny how your voice always breaks at the wrong moment, isn’t it?

‘It doesn’t matter. Nobody’s going to know. It’s going to make money and that’s beautiful.’

‘Is it?’

Wanda Zonker speaks what I later learn is one of the great truths of the beauty business.

‘Anything that makes money is beautiful,’ she says, almost reproachfully. ‘Drop your shoulder and turn a bit more to the right. You’re showing too much puppy fat. We’ll have to work at those inches, won’t we?’ Her voice suddenly goes all husky and her shadow falls across one of the lights. ‘You’re still tense, aren’t you?’ She is now standing so close to me that her bristols are brushing my shoulder,

‘I’m not used to this caper,’ I say.

‘It’s the sex thing, isn’t it?’ she says.

‘Not exactly,’ I say.

‘You’ve no need to be ashamed. It’s a fairly common hang up.’ While she talks, her fingers are brushing against my hang down. ‘I come up against it every day.’

‘Really?’ I say. ‘Can I put this thing somewhere for a moment? My arm is getting tired.’

‘Of course.’ Miss Zonker brushes her lips against one of my biceps. ‘I think it would be a good idea if we broke off for a bit.’ Percy is now in a very breakable condition and I clear my throat nervously. Miss Z moves her hands to my shoulders and I breathe easier. ‘You’re thinking of me as a sex object, I can tell.’ She looks down between our bodies and we both know what she is talking about. ‘I think maybe we’d better get this thing out of the way, don’t you?’

I am not quite certain what ‘thing’ she is talking about but I am too shy to ask. That is why I learned so little at school. If I had my time again I would always ask.

‘Uuum,’ I say, to show that I have been thinking about it. ‘Whatever you think is best.’

‘I don’t want a sound working relationship to be sullied by any feelings of guilt emanating from a suppressed libido.’ She is a lovely talker, isn’t she? They must be very handy with the languages in Lithuania – very handy with the hands, too. Percy is practically going into orbit. I feel so uncouth behaving like this, but then, when you have an action man kit like mine you don’t have a lot of alternative. It sort of takes you over.

‘Excuse me.’ Miss Zonker peels herself away from the front of my body and pulls open a cupboard. Like a shelfful of imprisoned moggies, a bundle of furry rugs bounds into her arms. She tosses them onto the floor at my feet and prods one with her toe. ‘Lie down,’ she says.

I am very glad of the opportunity to wriggle into a bit of cover because I feel a right nana standing under the arc lights without as much as a dab of athlete’s foot powder to deaden the shine on my shimmering torso. Down at floor level it is much cosier. That fur feels fantastic against your skin! I do hope it is not habit forming. I would hate to feel that I had to borrow Mum’s fox stole next time I felt like a spot of nooky. You would have to watch the teeth, too, wouldn’t you?

‘That’s nice. Face me. Don’t smile.’ CLICK!

She is still taking photographs. I feel like a one hundred-and-eighty pound baby on a tiger skin rug.

‘Can you move –? No. A bit more – no. Let me –’

‘Ooh!’ She certainly knows how to arrange her sitters. CLICK! I have only just stopped blinking when she burrows into the furs beside me and snuggles close.

‘Now, where were we?’ she says. I don’t think she really expects an answer because her hands dive deep down below where my legs become one big happy family and start drawing themselves up and up and – ooooooh!

‘The massage is the medium,’ she murmurs.

‘Definitively!’ I agree with her.

The camera clicks and I wonder whether to tell her that she has forgotten to turn it off. I don’t give it a lot of thought because Wanda Zonker has ways of taking your mind off things.

‘Is that nice?’ she says.

‘Fantastic,’ I say. ‘Do you want me to do it to you?’

‘You can’t do it to me,’ she says.

‘I know. I mean, something like it.’

‘All right. Gently now … gently. Use your fingers like the tip of an artist’s brush … aaaaaargh! That’s better.’

All the time she is talking her own fingers are doing a spot of hampton courting and I feel that I must express my gratitude in practical terms.

‘Aaaah,’ she sighs. ‘That’s heaven. I can see you’re becoming less inhibited already.’

I don’t say anything because Mum always told me it was rude to speak with your mouth full.

CHAPTER 2 (#u2e95039a-49e6-57c7-a8bd-d67379a60aa1)

‘Centre spread of Woman Now!’ says Sid sourly. ‘All right for some, I suppose.’

‘I believe they did a lot of retouching,’ I say.

‘They’d have to, wouldn’t they?’ sneers Sid.

‘On the body hues,’ I say. ‘Come on, Sidney. There’s no need to be like that. Just because I was the first British Mr November in the magazine’s history. I had no idea they were going to use the pictures.’

‘I can’t see why they did it,’ moans Sid, looking me up and down. ‘There must be hundreds of blokes with better physiques than you. Blokes who have whittled themselves down to a tight knot of whipcord muscle. Blokes like me for instance.’

‘I think you may have whittled a bit too far,’ I say. ‘Wanda told me that she daren’t use you in case your dongler got obscured by one of the staple holes.’

Well, I don’t want to boast but I have never seen Sid in such a state before. He is practically begging me to ring up birds he has not seen for ten years to prove that there is nothing wrong with his equipment. Of course, I made the whole thing up so I just sit back and enjoy myself. It goes to show how some blokes are always worried that another bastard has got a beauty that plays Land Of Hope And Glory while it submerges. I say ‘another’ but I reckon that we are all a bit like that. I know I am. The trouble is that you never see the opposition on the rampage, do you? You don’t know what you’re up against – or rather, what the bird you fancy is, was or has been up against. You see a bit of the placid flaccid when you’re in the changing room at the baths but – unless you lead a very exciting private life – it is not often that a male nasty in full flight skims past your peepholes.

I know they say in all those books that size does not matter but if I don’t believe it, what chance have you got of convincing a bird? The books have got to say that, haven’t they? I mean, you can’t spell out the brutal facts too bluntly, can you? Some blokes might decide to knot themselves. It seems obvious to me that a whopperchopper is going to turn a bird on like a good pair of top bollocks do a bloke. Anyway, the point is that Sid is reeling on the ropes and things don’t get any better for him when he sees my fan mail. Really! Some of those letters! Talk about ‘come up and see me sometime’. It is more like ‘drop ’em and cop this!’ No finesse at all.

‘I am slim, blonde and very adventurous and I would like to make love to you until the cows come home.’ Some of the ones from women don’t mince the monosyllables either.

‘Blooming nutcases!’ snorts Sid. ‘Nobody in their right mind would want to be mixed up in anything like that.’

‘Just wait till I’ve finished signing these photos,’ I say. ‘Oh dear, I wish I had a shorter name sometimes.’ I raise my hand to my mouth. ‘Sorry! I shouldn’t have said that.’

‘Said what?’

‘About being short.’

Sid turns scarlet. ‘Will you belt up! There’s nothing wrong with me, I tell you.’

Honestly, it is like taking candy from a kid.

Soon after I have been asked if I will stand as a Liberal candidate, Sid leaps round to Scraggs Lane with his face wreathed in smiles.

‘It’s settled!’ he says. ‘Wanda has come to an arrangement with Sir Henry. She’s been after his seat for a long time.’

This does not come as a complete surprise to me. She did a few funny things when I was with her. Nice but – well – funny.

‘I’m very happy for them,’ I say.

‘Long Hall,’ says Sid gazing into the distance.

‘Was it?’ I say. ‘I suppose she wanted time to be certain.’

‘What are you blathering about!?’ says Sid, unpleasantly. ‘I’m talking about Long Hall, Sir Henry’s country seat. We’re going to turn it into Beauty Manor. Don’t you remember anything you’re told?’

‘It all comes flooding back, now,’ I say. ‘I’ve been so busy with the modelling that I haven’t had time to keep up. By the way, Sid. When do I get paid for all this?’

Sid waves his hands in the air as if trying to dry them quickly.

‘I don’t know. You’ll have to ask Wanda.’

‘But she told me to talk to you about it.’

Sidney closes his eyes. ‘Look, Timmo. We’ve got a lot on our minds at the moment. This health farm thing could be very big. It needs constant attention. You’ll get your money. I’ve never let you down yet, have I?’

‘You’ve never not let me down, Sid. The last time I asked you for some cash you owed me you said “leave it to me, Timmo”. That’s what I’ve been doing all my bleeding life, leaving you money!’

This kind of argument makes less impression on Sid than a caterpillar stamping on reinforced concrete but at least it ensures that he takes me with him and Wanda when they go down to Long Hall.

I am quite partial to the country, once you can get to it, and I have a nice game with Wanda seeing who is the first person to spot a cow – it takes us forty miles, and then it is hanging up in the window of a butchers. Sidney is a rotten sport and will not play. I think he is sulking because he did not think of the idea in the first place – though maybe he is still worrying about the size of his dongler. Acornitis is what I have taken to calling his condition. Every time we drive past an oak tree I shake my head and he goes spare.

‘Here we are,’ says Wanda when we are somewhere on the other side of Henley. ‘Turn right at the gates.’

We sail past a couple of stone lions holding shields in front of their goolies and I soak up the acres of rolling parkland sprinkled with clumps of trees. It is better than any nick or reform school I have ever been to. I never knew you could see places like this if you were not a lunatic or a con. At the end of five hundred tons of gravel is a warm redbrick house with two wings and hundreds of windows – looking at them makes me blooming glad that I’m not still in the window cleaning game. You could perish your scrim on that lot.

‘This isn’t the place, is it?’ I say. ‘Not all of it?’

‘All of it,’ breathes Wanda. ‘Europe’s most modern beauty farm.’

‘You can’t have bought it?’ I say. ‘It must be worth millions.’

‘We’ve set up a company which will run the estate as a beauty farm, restaurant and superior country club. In return for our management expertise and a share of the profits from the enterprise –’

‘And because Sir Henry Baulkit owes us a favour,’ interrupts Sid. ‘We have carte blanche to convert the house to meet the requirements of its new usage.’

I can’t recall what Carte Blanche looks like but I remember the name. She must be one of those posh interior decorators you read about in the dentist’s waiting room.

‘Where is Sir Henry going to live?’ I ask.

‘He has a house in town which he uses when Parliament is sitting. His wife and daughter will be moving into the dower house.’

‘What’s wrong –?’

‘ “Dower” spelt D-O-W-E-R, not D-I-R-E,’ says Sid. ‘Spare me the Abbott and Costello routine.’

‘No need to be so touchy,’ I say. ‘You never learn if you don’t ask.’

‘Can you see that doe?’ says Wanda.

‘You bet I can,’ says Sid. ‘We should make a million out of this little caper.’

‘I was referring to the deer,’ says Wanda coldly.

‘Tch, Sidney!’ I say. ‘You’ve got a little caper on the mind, haven’t you?’

Sidney’s reply to my botanical jibe is unnecessarily coarse and hardly suitable for repetition in a book of this kind. I am glad when we arrive at the pillared front door.

‘Blimey!’ I say. ‘Take a gander at that bird. It looks like the hat Aunty Edna wore at Uncle Albert’s funeral.’ I remember the item well because there was a lot of talk about it at the time in family circles. It was also considered that the choice of scarlet stockings was inconsistent with the impression of a woman trembling on the brink of physical collapse over the loss of a dearly loved one. No one was very surprised when she married the coal man two months later. ‘She always had dirty finger nails,’ said Gran, significantly.

‘That’s a peacock,’ says Sid, following my gaze. ‘Blimey. Haven’t you ever been to Battersea Park?’

‘Some bugger nicked them two days before I went,’ I say. It is funny, but now that Sid reminds me, I seem to recall that the keeper was reported to have seen a coloured bloke climbing out of the aviary. I suppose it could have been a coal man …

‘Don’t look for a door bell,’ says Sid scornfully. ‘Houses like this don’t have them. Fold your mitt round that piece of wire and give it a pull.’

I do as I am told and we are lucky to avoid serious injury when the lightning conductor comes hurtling down and misses us by inches.

‘It’s going to need a few bob spent on it,’ says Sid, wisely.

‘What do you think of the weathercock?’ says Wanda.

‘Not bad for the time of year,’ says Sidney. Sometimes I don’t know if he is trying to be funny. Before I have the chance to find out the front door opens. An elderly geezer wearing a stained tail coat and a haughty expression looks down his hooter at us.

‘We have all the clothes pegs we need,’ he says coldly and tries to close the door.

‘Hold on a minute, Roughage,’ says Sid. ‘It’s me. Remember? I came round with Sir Henry.’

‘I don’t even remember the two of you being unconscious,’ says the ancient retainer. I can sense that with two such ace gagsmiths as him and Sid together sparks are surely going to fly.

‘Roughage! Surely you remember me? I’m going to convert the house into a spa.’

‘You’re wasting your time. There’s a new Tesco just down the road.’

‘Stop trying to close the door on my foot! Miss Zonker and I have a perfect right to be here.’

‘Does she charm warts?’ says Roughage, showing faint signs of interest.

‘She charms anything,’ I say gallantly.

‘Shall I show him my credentials?’ says Wanda.

‘Don’t overdo it,’ says Sid. ‘You can have too much of a good thing.’

‘What about fortune telling?’ says Lizard Chops. ‘Her ladyship has been powerfully attached to the crystal ball in her time.’

‘Quality rather than quantity, eh?’ says Sid, sounding comforted. ‘I don’t know where you get the impression that we’re gypsies.’

‘And don’t park your caravans up by the pigs,’ says Roughage, who seems to be a bit hard of hearing.

‘You mean, because of the smell?’ says Sid.

‘That’s right. Two of the pigs passed out last time. We had to give them mouth to mouth resuscitation.’

‘How horrible!’ says Wanda.

‘It was. Both of them died.’ Roughage scratches his head thoughtfully. ‘Maybe there’s something in those toothpaste advertisements.’

‘Come, come, my good man,’ says Sid. ‘We can’t stand here talking all day. Miss Zonker and I have work to do.’

‘And so have I,’ says the grey-haired Roughage. ‘I’m supposed to be helping her ladyship move into the dower house. She’s very put out by the way things have gone.’

‘I’m certain Sir Henry has her interests at heart,’ says Sid. ‘Timothy, why don’t you give Roughage a hand while I help Miss Zonker decide where to put her equipment?’ He runs his horny hand up the small of her back and I imagine the evil little thoughts that are pelting through his mind – even an evil little thought likes to keep moving in a place like that.

‘Of course,’ I say. ‘Where shall we meet?’

‘Down by the lake,’ says Sid. ‘There’s a gazebo at the far end.’

‘He won’t still be there when I’ve finished, will he?’ I ask.

‘A gazebo is a kind of summer house,’ says Sid, as if pronouncing the words causes him pain. ‘You’ll have to become a lot more araldite if you want to be a success at Beauty Manor.’

‘You mean “erudite”, Sid,’ I tell him. ‘Araldite is something you use for sticking parts together.’

‘I’ve never found that necessary, myself,’ says the little Lithuanian knocker factory.

‘Whatever I mean, you’ve got to smarten yourself up,’ says Sid. ‘Everything here has got to be done with tremendous couth.’ He does not wait for a reply but scampers off hand in hand with Wanda. Roughage clears his throat and looks round as if for somewhere to spit.

‘I don’t hold with it myself,’ he says. In the weeks to come this is a phrase that falls frequently from his withered lips.

‘I suppose we’d better get on with it,’ I say.

Roughage looks me up and down with contempt. ‘No need to rupture yourself,’ he says. ‘We’ve got all day.’

I am about to point out that I have considerably less than all day when the ancient retainer beckons me into a room bigger than anything I have ever seen outside the labour exchange. There are pictures painted all over the walls, and the ceiling looks like the sky with a load of fat tarts lying on clouds and being touched up by cherubs. Quite saucy it is, really.

‘You don’t need a telly, do you?’ I say cheerfully.

Roughage looks sourer than a furry yoghurt. ‘Them Baulkits wouldn’t give you the time of day,’ he says. ‘They take the batteries for the cook’s transistor out of her wages.’ Before I can reply he walks over to a long polished table and picks up a cut glass decanter full of booze. Removing the stopper he takes a long swig. This is not easy because the mouth of the decanter is square and I can see why the front of Roughage’s suit looks as if it has been used for pressing out the lumps in a vat of treacle.

‘Elevenses,’ he says with a loud hiccup. ‘One of the perks of the job.’ He opens the lid of a silver cigarette box and slips his hand inside. ‘OW!’

When he has stopped jumping about I help him remove the mouse trap from his fingers and he sticks his digits in his cakehole. It is not a course of action I would have followed myself, but then, I never did reckon that mice were as clean as a bar of Lifebuoy.

‘It’s no wonder they can’t get the servants these days,’ he says. ‘Who would put up with that kind of treatment when they could be making more money as a toast master?’

‘You’d get fed up with making toast all the time,’ I say. ‘Anyway, the machines are taking over.’

Roughage gives me a funny look and for a moment, I think that he is going to say something. Then he takes another swig from the decanter.

‘What is it?’ I say.

Roughage smacks his lips together for a couple of moments and then an expression of extreme distaste begins to dawn on his face. ‘Syrup of figs!’ he shouts and pushes past me into the hall.

What a funny set-up, I think to myself. His taste buds must be a bit on the dicky side if he can make a mistake like that. I always thought that butlers were supposed to know their way round a bottle of plonk.

It is also clear to me that relations between employer and staff are not going to teach Ted Heath any lessons. Roughage seems to awaken feelings of distrust in the Baulkits and I am not entirely surprised. I would not leave him alone with my money box and a bent hairpin.

‘What are you doing here?’ I whip round to see a bird of about forty peering at me from the doorway. She is wearing a lot of makeup and a suspicious expression. Although a bit on the thin side she is definitely not undesirable. She plucks anxiously at a string of pearls and feeds a second helping of upper class accent into my lugholes.

‘You’re not a sex maniac, are you?’

‘No,’ I say, taken aback.

‘Oh.’ She sounds disappointed. Knickers! I always have to go and say the wrong thing. ‘Then what are you doing here?’

‘I’m helping your butler with the move,’ I say. ‘Are you Lady Baulkit?’

‘For my sins,’ says the bird, fluttering her eyelashes at me. ‘That’s the best way of marrying into the aristocracy, you know. When I met Henry I was wed to another.’

I nod understandingly. Dad has frequently pointed out to me that the upper classes get away with murder when it comes to sack jumping and make hideous mockery of the nuptial couch. He is dead jealous, of course.

‘He was a retired Lieutenant-Colonel in the Pay Corps and we lived in Scotland. I met Henry when he came up for the shooting.’

‘Grouse?’ I say.

‘No, the village post mistress. The role of mistress was one she filled for more than just the GPO. Her husband was a very jealous man. Henry was cutting his teeth on the Aberdeen Press and Journal at the time. He always had a penchant for journalism.’

‘I expect it came in very handy,’ I say, wondering what she is on about. These upper class bints are inclined to be gluttons for the rabbit. I remember from my window cleaning days how they would always be bending your lugholes over a muffin and a cup of jasmine tea.

‘It was love at first sight,’ she says. ‘Rude men have always appealed to me. In those days he would pull his pyjamas on over his riding boots. It took me six months of marriage to stop him wearing spurs in bed.’

I nod my head sympathetically. Fascinating how the other half lives, isn’t it? Oh well. Please yourself.

‘Does any of this stuff have to be moved?’ I say, looking round the room.

‘No. If you touched anything it would collapse in a cloud of dust. It’s upstairs that I need some help.’ She tries to flutter her eyelashes but they carry so much mascara that one set sticks together and falls on the floor. I gaze out of the French windows like a gent while she repairs the damage.

‘Are you from the village?’ she says.

‘No. I’m employed by Inches Limited,’ I say. ‘You’ve probably met my brother-in-law; Sidney Noggett?’

‘Does he have very cold hands?’ she says.

‘I don’t know,’ I say. ‘I don’t think anyone in the family has ever mentioned it.’

‘They’re probably used to it,’ she says. ‘You do get used to things like that. I remember my first husband – just.’

‘When you were living in Scotland?’ I say, trying to show interest.

‘No. Nairobi. Kenneth was my second husband. I met him in Kenya.’

‘That’s why you pronounce it like that, is it?’ I say, keeping the conversation bubbling along.

‘No,’ she says, coldly. ‘I have a friend at the BBC who explained it to me. Anyway, what I was trying to say was that he had very cold hands.’

I am not quite certain whether she means Kenneth, the first husband or the bloke in the BBC. On reflection, it does not seem to matter very much.

‘Where is Roughage?’ says her ladyship.

‘I think he was taken a bit short,’ I say, trying to put as good a face on it as I can.

Lady Baulkit picks up the decanter he was glugging from and holds it up to the light. ‘I’m not surprised,’ she says. ‘He’s been at the syrup of figs. Ghastly old man. I don’t know why Henry keeps him on. Sentiment, I suppose. He’s been attached to the family so long we call him verruca.’

I nod understandingly and come to the conclusion that Lady Baulkit has a very nice set of pins. I have never been so close to a titled bint before and the experience sends a nervous tremour through my action man kit. Of course, it is too much to hope for that a spot of in and out might be on the cards but the thought alone is enough to send a warm glow skipping the length of my love portion. You only have to sound all your aitches to make me score heavily on the humble meter.

‘Of course, it’s not easy for a woman.’ Lady Baulkit’s voice trembles and she looks deep into my mind – about six inches deep. ‘The responsibility of the house and servants. Henry is away most of the time.’ She stretches out a hand and touches my wrist. ‘A woman has needs.’

‘Too true,’ I gulp. ‘Well, I – er suppose we’d better go upstairs.’ I mean, of course, to help with moving her things. I hope she does not misunderstand me. I step towards the door.

‘Don’t go that way. We’ll take a short cut.’ Lady B glides to the fireplace and grabs one of the carved cherubs by his John Thomas. Ouch! – it makes me wince to see her do it. A flick of the wrist and – blimey! A panel beside the fireplace slides open and I can see a flight of stairs.

‘In the old days, this is what you had to do to get into the priest’s hole,’ says her ladyship.

‘Really,’ I say. It is not a subject I feel keen to pursue. I believe that they had a lot of funny habits in those days.

‘There’s a network of secret passages connecting most of the rooms in the house,’ says Lady B. ‘Charles II used to stay here a lot with his lady friends.’

‘Very nice, too,’ I say. ‘Do we need a torch?’

‘Just take my hand.’ Lady B grabs my mitt before you can say ‘Kismet’.

‘Blimey! It’s dark, isn’t it? Are these stairs safe?’ The panel has slid shut behind us and my guide laughs lightly.

‘That depends who you’re with,’ she says.

I don’t want to jump to any hasty conclusions but a number of things that she has said and done suggest that she may be a bit on the fruity side – like a ton and a half of sultanas, for instance.

Now that we are in what you might call an enclosed space, her perfume begins to run riot through my conk and the sound of her silk dress swishing in the darkness awakens what my old headmaster used to call unhealthy thoughts.

‘It’s rather fascinating,’ breathes Lady B. ‘There’s a number of peepholes along here. You can keep an eye on the staff if you have a mind to.’ She pauses so that I nearly bump into her and pulls something aside so that a crack of light appears. ‘Look,’ she says after a pause. ‘Cook is rolling out the pastry.’

I apply my eye to the crack and – blimey! Cook is indeed rolling out the pastry – with the help of Roughage. He has made a remarkable recovery and is performing with no little agility for a man of advanced years. Another dollop of dough drops onto the floor and he kicks it savagely under the table. I must make a point of steering clear of the flap jacks – especially the ones with a seam.

‘The staff seem to get on well with each other,’ I say, deciding that some comment is probably expected of me.

‘Yes. I’m surprised that cook still has it in her.’

‘She doesn’t any more,’ I say, removing my eye from the crack. Short but sweet is probably the best that can be said for Roughage’s doughnut filler.

‘You have to be so careful with your menials, these days,’ murmurs Lady B. ‘Rub them up the wrong way and you’ve got a nasty problem on your hands.’

I feel myself blush scarlet in the darkness. I know we live in emancipated times but I never like to hear a woman talking like that. It’s not nice, is it?

‘This is the Seymour Room along here,’ she says. ‘One of the largest four posters in the country.’ She applies one of her mince pies to another peephole and gives a sharp exclamation of disgust. ‘Well, really! They might have taken the counterpane off first.’

I try to get a shufti but she shrugs me aside and flicks open another peephole. ‘Twin-viewing,’ she says. ‘It’s no fun going to a show by yourself, is it?’

I grunt my thanks and we settle down to take an independent view of the proceedings. My first glance explains to me why they call it the Seymour Room. I have not seen more in a long time. This bird is lying on the bed absolutely starkers and there is some bloke zooming over her contours like a Flymo Lawnmower. I can’t see his face, and I don’t reckon she can, the way he is heading. It is definitely for mature adults and I feel Lady B stiffen in the darkness. She is not the only thing. Percy gets the message that good times are rolling and starts trying to clamber over the front of my Y-fronts like he is on a Royal Marine Commando assault course.

‘Who are they?’ breathes Lady B. ‘It’s bad enough when the house is open to the public without complete strangers –’ She stops just as Sidney comes up for air.

‘You recognise him, do you?’ I say.

‘The one with the cold hands! What’s he doing here?’

‘He’s practising giving the kiss of life to a bird who has got a coal scuttle wedged over her nut,’ I say.

‘Don’t be facetious! I mean, why is he here at all?’

‘He’s siting Miss Zonker’s equipment,’ I say. ‘You must know all about Inches Limited and Beauty Manor. Your husband is one of the directors.’

‘He never tells me anything,’ she says. ‘Our marriage is a marriage in name alone. I’m expected to vacate my home so that perfect strangers can fornicate in it while he cavorts in town. I ask you: is that fair?’

‘Not bad,’ I say, concentrating on what I can see through the keyhole.

‘I’ve mouthed a few imprecations in my time, I can tell you.’ She doesn’t mind what she says, does she? I reckoned she might be a nunga nibbler when I first saw her. You can tell, you know. It’s something about the way her eyes shine.

‘Smashing,’ I say. Now Wanda has got on top of Sid and is pinning him down with her arms while she bashes out the theme of Ravel’s Bolero on his magic poundabout. It is not exactly the bedrock of children’s television but it is absorbing viewing.

Lady B obviously agrees with me. ‘You can imagine how I feel watching that,’ she says. I don’t have to imagine for long because her hand steals out and draws one of mine to her. She seems to be trembling.

‘You feel very nice,’ I say.

A fine haze of dust is now falling from the top of the four poster bed and the whole structure is vibrating like a tin shit-house in a hurricane. A grand stand finish is clearly on the cards and one of the pictures on the wall at the end of the room crashes to the floor.

Lady B. groans. ‘That’s a Van Dyck.’

‘He’s very versatile, isn’t he?’ I say. ‘Though I didn’t think much of his English accent in Mary Poppins.’

Further discussion on matters artistic is denied us because the canopy over the four poster bed collapses in a great cloud of dust and rat shit.

I am not sorry that the sight of Sid on the job has been banished from my eyes because it was getting a bit heavy. Once he turns purple and his eyes glaze over I would rather watch a good horror movie. It is like those Swedish films when they start all that thrashing and moaning. It quite puts me off my cornflakes.

‘My God. That’s priceless!’ yelps Lady B.

‘It is a bit funny, isn’t it?’ I say. ‘Especially with his legs sticking out of the end.’

‘I meant – oh! It’s too awful!’ Her voice is almost a shriek and it is a good job that Sid and Wanda are in a somewhat muffled condition. It would be most unfortunate if their concentration was shattered.

‘Supposing we can’t get it up?’

She is a very funny woman, this one. There is no doubt about it. Not only forward but pessimistic with it. I think maybe that her mind has become a bit unhinged due to lack of oggins. Because she can’t get it she has to try and persuade herself that it wouldn’t work anyway. Maybe this is a case for SUPERDICK – yes! I can see it all. Somewhere behind the wainscotting of ancient Long Hall, attractive Lady Baulkit yearns for a spot of in and out like what she can see being dished out in the appropriately named Seymour room. Beside her, simple unaffected Timothy Lea cowers in the darkness and feels the change in his pockets – the change that will turn him into: SUPERDICK!

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию (https://www.litres.ru/timothy-lea/confessions-from-a-health-farm/) на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Timothy Lea

It’s your duty to be beautiful…Another exclusive ebook reissue of the bestselling 70s sex comedy series.Bosky Dell Health Spa – relaxing, bracing – and absolutely full of women…Mrs Chalfont doesn’t seem at all tired by the early mornings and modest breakfasts, though – and she seems to want to work off her excess energy with Timmy and Sid…Also Available in the Confessions… series:CONFESSIONS OF A WINDOW CLEANERCONFESSIONS OF A LONG DISTANCE LORRY DRIVERCONFESSIONS OF A TRAVELLING SALESMANand many more!

Confessions from a Health Farm

BY TIMOTHY LEA

Contents

Title Page (#u1e9eb89f-7e0b-56e3-87af-09921a8ea1e1)

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Also available in the CONFESSIONS series

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Also by Timothy Lea & Rosie Dixon

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher

CHAPTER 1 (#u2e95039a-49e6-57c7-a8bd-d67379a60aa1)

‘I got a post card from Nutter, today,’ says Sid, pushing away his tea cup as if he never wanted to see one again – with Mum’s tea you feel like that.

‘That’s nice. How is he?’ I say.

‘Difficult to tell. Most of it has been crossed out by the censors. He seems a bit under the weather, though – not surprising when you think how much it rains over there.’ Sid laughs heartlessly.

I pick up the postcard: ‘The paddy fields, Ho-lung-ti.’

‘It looks nice, doesn’t it,’ I say. ‘The mountains and all that in the background.’

‘Blooming marvellous,’ says Sid. ‘I envy those boys, really I do. Doing away with National Service was the worst thing we ever did in this country. I remember how disappointed I was when they stopped it just before I was due to be called up.’

‘Why didn’t you sign on, then?’

Sid looks uncomfortable. ‘It wouldn’t have been the same, would it? I mean, I wanted to go in with all my mates, didn’t I?’

‘They could have signed on as well, Sid.’

Sid shakes his head. ‘Not everybody feels the same as I do about this septic isle, Timmo. I’ve only got to hear the opening bars of Land Of Hope And Glory and I’m rummaging through Rosie’s Kleenex.’

I tear my mind away from this affecting thought and examine the postcard. The first word is scratched out and followed by ‘you’ and an exclamation mark. Then comes another ‘you’ followed by three words that have been crossed out followed by a double exclamation mark. Fortunately, though it would have been unfortunately, had I been of a sensitive disposition, I can still read one of the crossed-out words.

‘I don’t reckon it was the blokes in Taiwan that censored this, Sid,’ I say. ‘It must have been our lot. Nutter isn’t half having a go at you.’

Not that I blame the poor sod. If you read Confessions of a Pop Star you will recall that Nutter and a group called ‘Kipper’ were rail-roaded out to Taiwan, that used to be Formosa like Alvin Stardust used to be Shane Fenton, by Sidney Noggett who still is my brother-in-law. They thought they were going to promote their chart-busting record but Sidney had arranged for them to promote the Taiwanese war effort by signing them on for five years in Chiang Kai-Shek’s army. Sidney does not usually go to this amount of trouble for people unless they are costing him money and there is little doubt that ‘Kipper’ were becoming an expensive luxury.

Sid picks up the postcard. ‘It’s a nice stamp, though, isn’t it? I’ll save that for little Jason.’

‘You never think about them, do you?’ I accuse. ‘Thousands of miles from home and with none of their own kind near them.’

‘They never have any of their own kind near them,’ says Sid, bitterly. ‘You tell me one person who is as greedy, lazy and useless as they are.’

‘I don’t want to hurt your feelings, Sid,’ I say after I have thought about it for a minute.

Sidney waggles his finger at me. ‘That’s very naughty, Timmo. You know how sensitive I am.’

I take a long look at the poor little suffering tea leaves at the bottom of my cup and decide to change the subject. ‘What’s this new idea of yours, Sid?’ I ask.

‘It’s a gold mine,’ says Sid.

My heart sinks. I can just see it. Some clapped out National Coal Board reject that Sid has been conned into buying. Broken down lifts, flooded galleries, no pit head baths, worked out seams. And who will end up thousands of feet below the earth with a Mickey Mouse torch tied to his bonce and a kiddy’s spade in his mitt? That’s right, yours bleeding truly.

‘I’m sorry, Sid,’ I say. ‘I don’t want any part of it.’

‘But you haven’t heard what it is yet!’

‘I don’t care about the details. I’m not going down any mine.’

Sidney claws the air in exasperation. ‘I was talking metaphysically, wasn’t I? I don’t mean a real gold mine. I never fancied mines after I saw Shaft.’

‘Shaft wasn’t about mining, Sid.’

‘You mean that big, black bloke didn’t have coal dust all over his mug?’

‘No, Sid! He was born like that.’ Honestly, you worry sometimes, don’t you? They say that there are over a million illiterates in the country and I reckon that they lie pretty thick around Scraggs Lane.

‘Oh,’ says Sid. ‘That explains a lot of things.’

‘What about the new idea?’ I say.

Saying that to Sid is like striking a match to find a gas leak, but somehow I can’t help myself. I have been stuck with Sid for so long that I cannot break away. Like a junkie begging for his fix I must know what half-baked scheme the Maestro of Muddle has come up with now.

Sidney leans back nonchalantly and rests his elbow in the frying pan that Mum has left on top of the cooker. Like everything on the cooker, including the rings, it is coated in half an inch of grease and is well equipped to become the first item of hardware to swim the Channel. Sid’s safari jacket therefore has to make a quick trip into the interior of the washing machine before the great white hunter can continue.

‘Do you know what is the biggest problem facing this country today?’ says Sid.

‘Inflation?’ I say. I mean, I listen to the party political broadcasts, don’t I? There is no bleeding alternative.

‘In a manner of speaking,’ says Sid, slightly downcast. ‘Obesity was the word I had in mind.’

Well, it is a free country, isn’t it? I can’t tell him what words to put in his mind, although they would have to be blooming small to fit into that tiny little space. I would have thought that you needed to fold ‘obesity’ in half to get it in without touching the sides.

‘Oh yes,’ I say.

‘You don’t know what obesity means, do you?’ says Sid, triumphantly.

‘No,’ I say. ‘That’s why you used it, isn’t it?’

‘It means being fat.’ Sidney looks me up and down critically. ‘About ninety percent of the people in this country weigh too much.’

‘That’s amazing,’ I say, stretching out my hand for another doughnut.

‘You for instance,’ says Sid. ‘It’s disgusting to see a bloke of your age falling apart at the seams.’

‘What are you rabbiting on about?’ I say. ‘I’m in perfect physical condition. I could run rings round you any day of the week.’

‘You must have put on a stone since you came out of the army,’ continues Sid. ‘You’ve got the beginnings of a paunch and there are rolls of fat building up round your waist. I can’t imagine how you do it. Living here I’d have thought that you had a bloody marvellous incentive not to eat.’

Sid is, of course, referring to Mum’s cooking. He has never had any time for her since she tried to boil a tin of sardines. Mind you, she is diabolical in the kitchen and maybe that is why I eat so much. I am forced to have a go at the nosh she dishes up and I also eat between meals to take away the taste and give myself a little reward.

‘You’re no oil painting,’ I say.

‘I’m fitter than you are, mate. Feel that.’

‘Sidney, please!’

‘I meant my stomach, didn’t I? Don’t take the piss.’

‘I don’t want to feel your stomach, Sid.’

‘Go on!’ Sid is speaking through clenched teeth as he tenses his muscles. Reluctantly, I stretch out a hand.

‘It feels like a pregnant moggy,’ I say.

Sid does not respond well to this suggestion. ‘Bollocks!’ he says. ‘Like ribs of steel, my stomach muscles. You try hitting them.’

‘Sidney, please! This is bloody stupid.’

‘Hard as you like. Go on!’ Sidney stands up and swells out his belly invitingly.

‘I don’t want to hurt you, Sid,’ I say.

‘You can’t hurt me! That’s what I’m trying to tell you, you berk! I’m in shape, I’m fit, I’m – uuuuuurgh!’

I give him a little tap in the stomach and he collapses on the floor, spluttering and groaning. Mum comes in.

‘He hasn’t been at the bread and butter pudding, has he?’ she says, alarmed.

‘No, Mum.’

‘Thank goodness for that. You were right, you know. Some of those sultanas were blue bottles. I think I’ll have to throw it away. It’s such a fiddling job picking them all out.’ She looks down at Sid. ‘What’s the matter with him?’

‘He was showing me how fit he is,’ I say.

‘He hit me when I wasn’t ready,’ wheezes Sid. ‘That’s what happened to Houdini.’

‘Oh dear,’ says Mum. ‘That doesn’t sound very nice. I wouldn’t stay down there if I was you. It’s not very clean.’

Sid drags himself to his feet and slumps into a chair. Mum was right. He looks like the inside of a carpet sweeper.

‘You did that on purpose,’ he grunts.

‘Of course I did,’ I say. ‘You told me to.’

‘You haven’t put anything in the washing machine, have you?’ says Mum.

I sense Sid stiffen. ‘What’s wrong with it?’ he says.

‘I don’t know,’ says Mum. ‘The man hasn’t been yet. I think it spins round too fast. Either that or there is a rough edge in there.’

Sid springs to the machine and presses the programme switch. He wrenches open the door and a couple of gallons of water thwack against the far wall.

‘I didn’t notice that was in there,’ I say. I am referring to the well-worn chammy leather with pockets.

Sid groans. ‘Eighteen quid that cost.’

‘Blimey! That’s your safari jacket, isn’t it?’ I say.

‘Don’t sound so bleeding cheerful,’ snarls Sid. ‘You ought to have put an “out of order” sign on it.’

‘I did,’ says Mum. ‘But I moved it to the bread and butter pudding.’

‘Gordon Bennett!’ Sid covers his face with his hands.

‘Sid has got a new idea,’ I say, deciding that it is time for another change of subject. ‘It’s something to do with fat people.’

‘I’m going to classes now,’ says Mum. ‘Do you think I look any different?’

‘You look a bit paler, Mum,’ I say.

‘Don’t say that! I was thinking how well I looked. I’ve lost half a stone, you know.’

‘Where did you lose it, Mum?’ I ask.

‘Round the bum, mostly,’ says Mum, with an honesty I could have done without.

‘I didn’t mean that,’ I say hurriedly before she can impart any more revelations. It’s not nice listening to your parents talk about their bodies, is it? It is bad enough having to look at them.

‘The Lady Beautiful Health Clinic,’ says Sid. ‘That’s what I’m on about. More and more people are becoming worried about the condition of their bodies. You mother is only following a trend.’

‘You want to be careful, Mum,’ I say. ‘You remember what happened when you tried that yoga.’ I have to suppress a shudder when I think about it. Everywhere you went in the house there would be Mum standing on her head against one of the walls. And often without any clothes on! Yoga Bare, that’s what Sid used to call her. Luckily she bombed out in the Padandgushtasana position and we did not hear any more about it.

Further discussion is interrupted by the sound of the front door bell.

‘Who’s that?’ says Sid whose reaction to the unexpected reveals a permanently guilty conscience.

‘Probably Dad’s lost his front door key,’ says Mum. She leaves the kitchen and pads off to have a peep through the front room curtains. A couple of minutes later she returns.

‘There’s a gorilla standing on the front door step,’ she says.

‘A stuffed one? With Dad?’ says Sid.

‘No, it’s carrying a briefcase,’ says Mum.