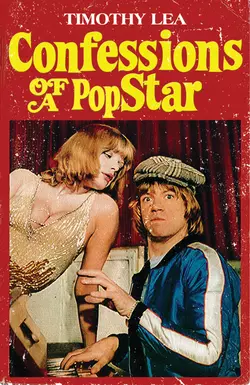

Confessions of a Pop Star

Confessions of a Pop Star

Timothy Lea

Pop music, screaming fans, incredible tours – being a Pop Star certainly has rewards…Available for the first time in eBook, the classic sex comedy from the 70s.Timmy Lea needs a new job, and Noggo Enterprises promise to make him a star.But can he navigate his brother-in-law Sid? Their certainly seem to be lots of adoring, receptive fans, who all want a piece of him – in bars, in cars, and in seedy hotel rooms.Also Available in the Confessions… series:CONFESSIONS OF A WINDOW CLEANERCONFESSIONS OF A LONG DISTANCE LORRY DRIVERCONFESSIONS OF A TRAVELLING SALESMAN

Confessions of a Pop Star

BY TIMOTHY LEA

Contents

Cover (#uca1f6db8-8e13-57b2-907d-6626e8a4458d)

Title Page (#u2bbaf576-f3ab-5ca1-9431-1bce8767fcf3)

Publisher’s Notes

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Also available in the CONFESSIONS series

About the Author

Also by Timothy Lea & Rosie Dixon

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher

Publisher’s Note (#u9230fa46-0ae0-540f-b51a-f3c527191deb)

The Confessions series of novels were written in the 1970s and some of the content may not be as politically correct as we might expect of material written today. We have, however, published these ebook editions without any changes to preserve the integrity of the original books. These are word for word how they first appeared.

Chapter One (#u9230fa46-0ae0-540f-b51a-f3c527191deb)

In which a talent spotting trip to the East End with brother-in-law, Sid, involves Timmy in an unseemly fracas and two close brushes with the opposite sex.

‘Gordon Bennett!’ says Dad. ‘Most people can get out of the nick easier than the army. “Dishonourable Discharge.” Sounds like what we used to find on the front of your pyjamas.’

‘Dad, please!’ I mean, that kind of remark is so uncalled for. Anyhow, I never had a pair of pyjamas when I was going steady with the five-fingered widow.

‘This latest disgrace has dropped us right in it with the neighbours. I don’t know where to put my face.’

‘Why don’t you try some of the places Sid has been suggesting all these years?’ It is sad, but Dad always brings out the worst in me.

‘You leave your sponging brother-in-law out of this. Just consider what you’ve achieved in the last five years. You’ve broken your mother’s heart and now you’ve damn near done for mine. In the nick twice and God knows how many jobs you’ve had.’

‘The first time was only reform school, Dad.’

‘That’s shredded in the mists of antiquity, that is. Why can’t you be like your sister? A nice home, two lovely kiddies. She’s done all right for herself.’

‘I couldn’t find the right bloke to settle down with, Dad.’

‘I don’t expect it’s for want of trying, though. That’s the one thing we haven’t had from you, isn’t it? I’m waiting for you to turn into a nancy boy. That’ll be the final nail in my coffin.’

‘I’ve started a whip round for the hammer, Dad.’

As might be expected, Dad is not slow to take umbrage at this remark.

‘That’s nice, isn’t it? Bleeding nice. That really puts the kibosh on it, that does. You sacrifice your whole life to your kids and what do you get? Bleeding little basket wants to see you under the sod.’

‘One on top of the other, Dad.’

Dad steams out of sight and I consider what an ugly, weasel-faced old git he is. It is amazing to think that he could have produced something as overpoweringly lovely as myself. Sometimes I wonder if he actually did have a hand in it – or something more intimate. I have always found it disgusting to think of my Mum and Dad on the job but the thought of some invisible third-party – a prince or something like that – giving Mum one behind Battersea Town Hall seems much more favourite. The arse is always cleaner on the other side of the partition, if you know what I mean.

Of course, to be fair, you can understand Dad being a bit narked. When I was conned into signing on as a ‘Professional’ for nine years, he must have thought that he could fill every inch of my bedroom with nicked stuff from the lost-property office where he works. I use the word ‘work’ in its loosest sense. Dad had to be carried into the nearest boozer when someone in his bus queue mentioned overtime. When Dad thought he had got rid of me, he reckoned without Sid’s ability to put the mockers on anything he comes into contact with. I will never forget the sight of Sid’s nuclear warhead drooping towards submarine level while the colonel’s lady shouted for action and all those Yanks with gaiters halfway up their legs bristled in the doorway. It is the nearest we have ever come to causing World War III. She was a funny woman, that one. Very strange. There can’t be many birds who fancy a bit of in and out under the shadow of the ultimate deterrent – still, I expect you read all about it in ConfessionsofaPrivateSoldier so I won’t go on. (Of course, if you did not read about it, there is nothing to stop you nipping round the corner and having a word with your friendly local newsagent. If you ask him nicely he might be able to find you a copy – to say nothing much about the other titles in the series. For instance, there is – ‘Belt up and get on with it!’ Ed. All right, all right! I’ve got to live, haven’t I. Blimey, these blokes think you can nosh carbon paper. I am not surprised that LesMiserables packed it in after one book.)

Anyway, getting back to the present. There I am at 16, Scraggs Lane, ancestral home of the Leas since times immemorial after an unproductive brush with HM Forces. It might have done Mark Phillips a bit of good but I did not as much as catch sight of a corgi’s greeting card the whole time I was in the Loamshires. Ridiculous when you consider how many Walls sausages the family must have eaten over the years. And talking of food, here comes my Mum, that commodity’s greatest natural enemy. The only woman to have burned water.

‘Stop going on, Dad,’ she says. ‘Tea’s on the table. I’ve got some nice fester cream rice for sweet.’

‘You mean, Vesta Cream Rice, Mum. “Fester” means to turn rotten.’

‘You want to taste it before you start telling your mother what she means,’ snorts Dad. ‘It doesn’t take a lot of prisoners, that stuff, I can tell you.’ Mum may be a diabolical cook but her heart is in the right place – and that saves an awful lot of trouble when you go for a medical checkup, I can tell you. It also means that she is always glad to see me home whatever I have done. She has even tried to spell out ‘WELCOME’ in the alphabet soup.

‘It’s funny,’ she says, gazing at me over the curling beef-burgers. ‘You look such a wholesome boy.’

Dad snorts. ‘I expect Jack the Ripper looked bleeding wholesome and all. Don’t start making excuses for him, mother. He’s never going to change. I’ve given up hope for him.’

‘Have you thought about what you’re going to do, now, dear?’ says Mum, absentmindedly straining the cabbage on to the beefburgers – at least it takes the curl out of them.

‘Sid’s got an idea about going into the entertainment business. I’m having a talk with him tonight.’

‘ “Entertainment?” But you don’t do anything.’

‘You can say that again,’ sneers Dad.

‘I know how you got that job at the lost property office,’ I say. ‘Someone handed you in, did they?’

‘Watch it, Smart Alec!’

‘Stop it, both of you. You know I can’t stand scenes. I still don’t see what Timmy is going to do. Sid doesn’t play anything, does he?’

‘Sidney Noggett has been on the fiddle for years,’ says Dad wittily. ‘That’s the only way you get anywhere, these days. A decent working-class man with a set of principles might as well stay at home.’

‘You do stay at home most of the time, Dad.’

‘It’s my back, isn’t it? There’s no cause to mock the afflicted. If me and a few more like me didn’t have our aches and pains you might be feeling the Nazi jackboot across the back of your neck.’

Dad does tend to over-dramatise a bit for a bloke who spent most of World War II fire watching. In fact I have known him turn off Dad’s Army because he found it too harrowing. Still, he is very sensitive on the subject and since my present standing in the family is one of grovelling I should be advised to lay off.

‘Sorry, Dad.’ The words are more difficult to form than the Bermondsey branch of the Ted Heath fan club.

‘I should bleeding think so. Young people today don’t know the meaning of the word patriotism. Look at us. Knocked out of the World Cup by a load of Polaks. The Krauts going mad in Munich. It’s a bleeding national disgrace.’

‘Come on, Dad. When your mate, Stanley Matthews, was playing we were beaten by the Yanks.’

Dad does not like this. ‘Sir Stanley Matthews if you don’t mind, Sonny Jim. That was the atmospheric conditions, wasn’t it? They made them play up the side of a mountain, didn’t they? Our lads weren’t used to it. I don’t call that football.’

‘Do give over, Dad,’ says Mum. ‘How do you like the beefburgers?’

‘I don’t reckon them boiled, I can tell you that.’ Dad did not see Mum straining the cabbage over them.

‘Just as you like, dear. I thought it might make a change.’

Mum does not bat an eyelid. ‘Eat up, Timmy. Your rice is all ready.’

Already ruined, I can see that. Once it starts making a bolt for it over the side of the saucepan you can reckon that it has given up the ghost.

‘I don’t know if I can manage it, Mum,’ I say, patting my stomach in a way that I hope suggests satisfaction with the excellent fare that has already been provided.

‘Go on. I know you can find room for it. I’ll put some golden syrup on it like I used to when you were a little boy. You remember how he used to love hot, sticky things when he was a kiddy, Dad?’

‘Yeah.’ Dad’s face adapts a thoughtful expression and I can sense his disgusting mind working on some tasteless descent into vulgarity.

‘Just a little bit, Mum,’ I say hurriedly, ‘I think I put on some weight in the army.’

‘I was thinking how thin you looked.’ Mum thumps down an enormous helping of what looks like petrified frog’s spawn. I do wish she would not use the spoon with which she dishes out the beefburgers. ‘There you are. Rice is the stable diet of the Chinese, you know.’

‘This lot looks as if it’s seen the inside of a stable and all,’ complains Dad. ‘Gordon Bennett! How do you manage to get it like that?’

‘I did what it said on the side of the tin,’ says Mum, patiently reading from the label. ‘ “Brown and crisp on the outside, moist and tender in the middle.” ’

Dad claps his hand to his head. ‘Gawd, give me strength! That’s the steak-pie tin, isn’t it? Can’t you even read from the right bleeding labels?’

‘Oh dear. It must be my glasses,’ says Mum.

‘Yeah, you want to stop filling them to the brim all the time,’ snaps Dad.

‘It wouldn’t be a surprise if I did turn to drink, the way you go on at me,’ sniffs Mum. ‘If the food isn’t good enough for you, you’d better give me some more house-keeping money.’

‘I daren’t do that,’ says Dad. ‘All you’d do is buy bigger tins.’

‘At least the print on the labels would be larger, Dad,’ I say helpfully.

‘Don’t you turn against me, now,’ sobs Mum. ‘I try and do you something nice when you come home and this is all the thanks I get.’

‘See what you’ve done now?’ snarls Dad. ‘You’ve made your mother cry. As soon as you’re through the door you’re spreading misery and unhappiness. If what you get here isn’t good enough for you –’

His voice drones on but it is a track from an LP I have heard a million times and the words disappear like raindrops into snow. I am meeting Sid round at his Vauxhall pad and I am not sorry when the time comes to steal away with Dad’s voice melting in my ear and a fistful of Rennies belting down to put out the fire in my belly. I am also looking forward to seeing sister Rosie again. When Sid last talked about her she had started up a couple of boutiques and was doing all right for herself. Ever since her little brush with Ricci Volare on the Isla de Amor she has been a different woman from the one that used to hover in front of Sid like the pooch on the old HMV label. I feel sorry for Sid. It can’t be nice for a bloke to see his wife doing something on her own – especially when she starts doing better than he is. Ever since the Cromby Hotel, Sid has been marking time if not actually going backwards while Rosie has been coming up like super-charged yeast. How will I find the girl who was voted Clapham’s ‘Miss Available’ in the balmy days of 1966?

The short answer is – thinner. Rosie’s tits seem to have evaporated and the skin is stretched over her face like the paper on the framework of a model aeroplane. She has also done something with her eyebrows – like got rid of them – and her barnet is closer to her nut that I can ever remember it.

‘Got to go out, Timmy love,’ she says, kissing me on the cheek. ‘Sidney will give you a drink. Must fly. See you again.’

Her voice is different, too. Not exactly posh, but sharper. It carries more muscle, somehow.

Sid looks relieved when she has pushed off. ‘What’s your poison?’ he says.

I am a bit disappointed with the surroundings. I had been expecting signs of loot, but they don’t even have a cocktail cabinet. The booze is laid out on a tray and that rests on a table which is definitely on its last legs. Peppered with worm holes and dead old-fashioned looking. Most of the stuff they have got must have come from a junk shop though the carpet is nice. Probably took up all their cash.

‘I’ll have a light ale, since you’re asking,’ I say.

Sid looks uncomfortable. ‘We don’t have any light ale. There might be some lager in the fridge.’

I look at the tray and he is right. It is full of bottles of gin and vodka and something called Noilly Prat. That sounds nice, doesn’t it? Just the kind of thing you would like to offer your mother-in-law.

‘Let’s go round the boozer,’ I say. ‘Where’s Rosie pushed off to?’

Sid is already helping himself to a large scotch. ‘She’s gone to look at one of her wine bars.’

‘Wine bars? She given up the boutiques, has she?’

Sid took a deep swig at his drink. ‘She’s got these as well as the boutiques.’

‘What is a wine bar, Sid?’

‘It’s like a boozer, but they only sell wine.’

How diabolical! My blood freezes over when I hear his words. I mean, I don’t mind a spot of plonk on the Costa Del Chips, that is the place for it, isn’t it? But in your own local – and pushing out the native product! It hardly bears thinking about. How could Rosie do such a thing? It must be a blooming disaster.

‘Making a bleeding fortune,’ says Sid.

‘Yerwhat?’ I say.

‘I thought she was round the twist but it’s amazing what people go for these days. Wine is dead smart, see? And a load of birds reckon it. You get a lot of posh bints in her places. They used to think it was all spit and sawdust down the boozer and you must be on the game if you went into one. A wine bar was different. That was refained, somehow.’

‘So it’s just a load of judies, is it?’ I say thoughtfully.

‘Used to be. Until there was this article in the paper that said just that. It went on about how a bird could drink in peace without being molested and that there were thousands of little darlings sipping their full bodied rioja–’

‘Blimey, they must have been desperate, Sid.’

‘That’s what everybody thought, Timmo. The day after the article appeared there were blokes fighting to get through the door. Now it’s just one great knocking shop.’

‘Poor Rosie. She must be heartbroken.’

‘Yes, she’s crying all the way to the bank. Do you want to see one?’

‘Not really, Sid. I’ve thought about opening an account but–’

‘I didn’t mean a bank, you berk! I was referring to one of Rosie’s wine bars. We could look in later.’

‘Very nice, Sid. But we’ve got some business to discuss, haven’t we?’

‘Too true, we have. All this chat about Rosie’s business.’

Success has whetted my appetite. If she can do it why not her attractive brother?

‘Right,’ says Sid knocking back his scotch. ‘Let me reiterate. I think there are some fantastic opportunities in the entertainment field. I don’t mean performing ourselves but finding talent and, and–’

‘Exploiting it?’ I say helpfully.

‘The word I was looking for was managing,’ says Sid, sternly. ‘But you’ve got the general idea. If we take the risk then it’s only right that we should take some of the profit.’

‘ “Some”?’ I say.

‘Nearly all,’ says Sid. ‘And we don’t want to let ourselves in for too much risk either.’

‘What exactly did you have in mind?’ I ask.

‘Park your arse.’ Sid waves me towards this scruffy old leather settee that looks like fifteen feet of Hush Puppies. It’s a shame really. A nice chintz cover would brighten the thing up a treat. I don’t suppose Rosie has the time.

‘The public are very fickle these days. You don’t know which way they’re going to turn. You’ve got to appeal to all age groups, as well. What I mean is, we can’t afford to have all our eggs in one basket. I learned my lesson when I got stuck with all those bleeding hula hoops and pogo sticks.’

‘What happened to them in the end, Sid?’ I am always interested in news of Sidney’s business ventures. It makes a change to have first hand suffering instead of all the stuff you read about in the papers.

‘I sold most of them off as a Christmas game. You hang up the hula hoop and chuck the pogo stick through the middle of it.’

‘Sophisticated stuff, Sid.’

‘Don’t take the piss, Timmo. Kid’s toys are far too bleeding complicated these days. All they want to do is smash things up. I got the idea for HULAPOG from Jason.’

Just in case you do not know or have forgotten, Jason is Sidney’s firstborn and as nasty a piece of work as ever smeared its jammy fingers down the inside of your trouser leg. Seven years old and dead lucky that he still has the wind left to blow out the candles on his birthday cake. There is also the infant Jerome who is the spitting image of his brother – all he does is spit.

‘He’s an aggressive little chap,’ I say.

‘Spirited is the word I would use,’ says Sid. ‘I wanted to talk to you about Jason. That kiddy has got charisma.’

My face falls. ‘Oh, Sid. I’m sorry to hear that. Still, they can do wonders these days if they get onto things in the early stages.’

‘What are you bleeding rabbiting about?’ snarls Sid. ‘There’s nothing wrong with him. He’s got star quality, that’s what I was saying. He figures large in my plans.’

My heart sinks until it is practically resting on my action man kit. ‘Not another David Cassidy,’ I groan. ‘You can’t walk down the street without tripping over some spotty kid belting out golden mouldies before his balls drop.’

‘Shut your face and listen,’ says Sid unsympathetically. ‘I want to give you the broad picture before we start going into details.’

‘We’re going to have broads, are we?’ I say, perking up a bit.

Ever since some half-witted bird told Sid he looked like Paul Newman he has been inclined to pepper his rabbit with Americanisms.

‘Are you trying to take the piss? I’m talking about the range of our activities, aren’t I? We want to appeal to all sections of the public so we got to get together a variety of acts. We want a kid for the teeny boppers, a group – and one of those Hermasetas would be a good idea.’

‘I don’t get you, Sid. They’re those little things you put in your coffee, aren’t they?’

‘I mean one of those blokes who looks like a bird. They’re very popular, they are.’

‘You mean a hermaphrodite, Sid.’ Sidney tries hard with the Sunday newspapers but when you have had most of your education off the labels on sauce bottles it is difficult not to get confused.

‘All right, all right. Have it your own way, Master Mind. As long as he can hold a guitar so the thin end is pointing towards the ceiling, that’s all I’m interested in.’

‘Where are you going to find all this talent, Sid?’

Sid produces a large cigar and shoves it into his cakehole. Somewhere in Central London, Lew Grade must be feeling icy fingers running up his spine.

‘Quantity is no problem, Timmo. It’s finding kids with the right qualifications. Dedicated, talented–’

‘And prepared to work for nothing.’

Sidney shakes his head slowly. ‘Somewhere along the line you’ve become cynical, Timmo. That’s very sad.’

‘Somewhere along the line I met you, Sid. Let’s face it, sentiment has never blurred your business vision.’

Sid shakes his head. ‘I don’t know what you’re on about. Look, if you’re interested in seeing how I spot talent you can come with me tonight. There’s a folk singer I want to have a decco at. Rambling Jack Snorter. He’s on at a boozer in the East End.’

My ears prick up when I hear the word boozer. I don’t fancy drinking at home except at Christmas.

‘What about the kids? Is Rosie coming back?’

Sid looks sheepish. ‘Gretchen can look after them.’

‘Gretchen?’

‘The au pair.’

Au pair? The words trip off the tongue like ‘knocking shop’, don’t they? I can just see her. Blonde, blue-eyed and with a couple of knockers like Swedish cannon balls. No wonder Sid is looking embarrassed. With his record he has probably been through her more times than the Dartford tunnel.

‘Don’t let your imagination run riot,’ sighs Sid. ‘Rosie chose her. She hasn’t won a lot of beauty contests.’

As if to prove his point a bird comes in with a complexion like a pebble dash chicken house. For a moment I think she is wearing a mask – when I take a good look at her I wish she was. I have seen birds with warts before – but not on their warts. I don’t go a bundle on her hair either. It is like mousy candy floss, or the stuff that comes out of your Bex Bissell. One feature you can’t fault her on is her knockers. They are right out of the top drawer – in fact they are so big they would fill the whole blooming chest. They certainly fill hers.

‘Ah, Gretchen,’ says Sid, putting on his ‘Another glass of port, Lady Prendergast?’ voice. ‘I don’t think you’ve met my brother-in-law?’

When I was a kiddy, I shut my digits in a car door. When Gretchen folds her mit around mine and applies ‘pleased to meet you’ pressure, the sensation is about the same. Strong? This girl could play centre back for Moscow Dynamo and only your shin bones would know the difference.

‘Pleased to do you,’ she grunts. ‘How do you meet?’

‘Gretchen is learning English at Clapham Junction College of Commerce,’ says Sid, chattily.

I nod agreeably while I try and rub the circulation back into my pinkies and Sid explains about us nipping out for a few jars.

Funny how first impressions can be misleading sometimes.

‘Must be a strain to control yourself, when you’ve got that about,’ I say as we scamper down the steps.

‘Yeah. I nearly swung for her a couple of times,’ says Sid. ‘She cooked us a stew once. I think she made it from old shaving brushes. Talk about diabolical. The cat took one look at it and ran up the chimney. We had a fire in the grate at the time, too.’

Sid still has his Rover 2000 and I feel like Lord Muck as I settle back against the leather and watch the Thames twinkling away like the froth on a pool of piss.

‘We should have time to catch Rambling Jack and have a decko at one of Rosie’s places,’ says Sid. ‘You know the East End at all, do you?’

I don’t really and it doesn’t look as if I am going to get the chance because they seem to be pulling it down even faster than the part of London I am living in.

‘Some right villains hang out around here,’ says Sid. ‘Mind how you go when you get the first round in.’

I reckon if Sid made a million you would still think he had fish hooks sewn to the insides of his pockets.

The Prospect of Ruin is packed out with everyone from candidates for ‘The Upper Class Twit Of The Year’ award to blokes who look as if they taught Bill Sykes how to scowl. You would think that two different dubs had booked on the same night.

‘The toffs come here because they fancy a bit of slumming,’ says Sid. ‘It’s the nearest most of them ever get to villainy until they join the stock exchange.’

‘Creme de menthe frappé and a packet of crisps?’ I say as I push my way into the crowd round the bar. Sid’s reply is not the kind of thing I would like to quote in a book that might find its way into the hands of minors – or even miners for that matter, and does not stay in my mind long. The reason? I find myself face to face with a really knock-out bint. She is dead class. You can tell that by the string of pearls round her neck and the little pink flushes that light up her alabaster shoulder blades.

‘I’m sorry,’ I say as I go out of my way to brush past her. ‘There’s a bit of a crush in here.’

‘That’s quite all right.’ Her voice goes up like the cost of living and she turns a few shades pinker.

‘Are you on your tod?’ I say. I mean, it’s favourable to ask, isn’t it? You don’t want to lash out on a babycham and find that there is some geezer with her.

‘I’m with friends,’ she says, very dainty like. I take a gander and see another filly and a couple of blokes who look as if their stiff white collars do up on their adam’s apples.

‘Be presumptuous of me to offer you a drink then, wouldn’t it?’ I often chuck in a long word like that because it shows an upper class bird that there is more to me than meets the thigh. I may not speak very proper but I have a way with me – I have it away with me too, sometimes, but that is another story.

‘Are you a waterman?’ says the bird, with a trace of interest.

‘Only when all the beer has run out,’ I say, wondering what she is on about.

‘Eewh.’ I don’t know if that is how you spell it but it sounds something like that. It is the kind of noise the Queen Mother would make if she found you wiping the front of your jeans with one of the corgis.

‘Daffers!’

The voice belongs to a herbert with a mug built round his hooter. Daffers makes another uncomfortable noise and pads off.

I get the beers in and join Sid.

‘You’ll never get anywhere with her, mate,’ he says gloomily. ‘Apart from the fact that she probably finds you repulsive, she’s not going to blot her meal ticket.’

‘I don’t know so much.’ Daffers keeps shooting glances at me and experience has taught me that where there is life there is poke. ‘When are we going to see old Rumbling Tum?’ I ask.

Sid does not have to answer because a bloke with a red velvet jacket appears on a small stage and grabs a microphone.

‘Good evening, ladies and gentlemen, and welcome to the Doom. Tonight we’re very fortunate to have a return visit from that popular son of the sod–’

His voice drones on but I find myself concentrating on a geezer with a big black beard who is clearly pissed out of his mind. He is barging into tables and cursing and muttering fit to kit out a TV comedy series. I don’t know why they haven’t chucked him out.

‘Do us a favour, Timmo. I don’t want to miss any of this.’ Sid shoves his empty glass into my hand and I am fighting my way back to the bar again. Blooming marvellous, isn’t it? Working with Sid is always the same. The outlay is more guaranteed than the return.

Daffers has not pressed forward with the rest of her mates and I can see her trying to think of something to say. That makes two of us.

‘You look like an ’ore,’ she says.

For a moment I cannot believe my ears. She looks such a nice girl too. What a thing to say. No bird has ever spoken to me like that before.

‘Nobody’s perfect,’ I say. Maybe it is the diamante on the lapels of my shirt. Mum thought it was a bit much.

‘I thought Thames Tradesmen were awfully unlucky at Henley,’

Now she has really lost me. What is she on about?

‘I’m in the entertainment business,’ I say. ‘Do you fancy something?’

‘I think I’ve had enough already.’

‘Force yourself.’

‘Well, a glass of white wine, please.’

Sidney must be right. They are all at it. And it costs as much as a pint of bitter, too. Diabolical!

‘ “And the brave young sons of Eireann came pouring through the door. And the snivelling British Tommies fell grovelling on the floor.” ’ I turn round and – blooming heck! The bearded git must be Rambling Jack Snorter. His accent is as thick as an upright shillelah and the first three rows are reeling under a hail of spittle.

I tear myself from Daffers’ side and return to Sid.

‘What do you think?’ he says.

‘He’s all right if you’ve got an umbrella,’ I say. ‘Does he always go in for this anti-British stuff?’

‘He’s very committed,’ says Sid.

‘And frequently, too, I should reckon,’ I venture. ‘I think he comes on a bit strong, myself.’

‘He’s controversial, I’ll grant you,’ says Sid. ‘But that’s a good thing these days. He can create a dialogue between himself and the audience.’

‘You mean, like that bloke who just threw a bottle at him and told him to piss off back to Ireland?’

‘That kind of thing, Timmo.’ Sid grabs me by the arm and steers me away from the stage. ‘I think we might see if his voice carries.’

‘Good thinking, Sid.’

‘ “So here’s to all brave Irishmen, God bless their sparkling eyes. And hatred to the English filth whom all true men despise.” ’

‘I like the idea of the fiddle,’ I say.

‘Yeah. But they break easily, don’t they?’

‘They do if that one is anything to go by. Does he always finish his act by being thrown out of one of the windows?’

‘Not usually,’ says Sid, ducking. ‘It’s just that some of these dockers are a bit touchy. They’re big men but very sensitive. Do you fancy another beer?’

‘I don’t think we’re going to be able to get one, Sid. That’s the governor draped over the partition, isn’t it?’

‘You’re right. It’s a lively little place, no doubt about it. I must come again some time.’

‘Give them a couple of years to rebuild.’ I duck as another bottle shatters against the wall above my head. If we keep under the table and push it towards the door we may be all right.’

Sid nods and turns up the collar of his jacket. ‘Yeah, I don’t like leaving the car for too long around here. Last time I was in the neighbourhood the kids were playing tiddly winks with hub-caps. Some little bleeder whipped my aerial. It wouldn’t have been so bad but I was doing forty miles an hour at the time.

Daffers is sheltering under a nearby table and I nod to her as we crawl past. ‘Super to meet you,’ she says. ‘Good luck with the rowing.’

‘What was she on about?’ says Sid. ‘What have you been telling her?’

‘Search me. I think she’s a bit touched.’

‘I wouldn’t mind touching her and all. Lovely the way her bristols were hanging down like that.’

The sight has not been lost on me and I would be very willing to show the lady that what I don’t know about rowing I know about in and out. I mean, it’s practically the same thing, isn’t it? Women on their hands and knees are always a favourite with me. A bit of dangle and a nice inviting curve to the backside – Down Lea!

We get to the car just as the fire engine comes round the corner and nearly collides with the first of the police cars.

‘Lovely publicity,’ says Sid, enviously. ‘It’s a shame we don’t have him under contract.’

‘Sign him up and you’ll have us all under six feet of earth,’ I say. ‘He’s a raving nutter, that bloke.’

‘He’s outrageous,’ agrees Sid. ‘But that’s what a section of the market wants, these days. I wonder if I could get him to wear drag and dye his hair purple.’

Sid rambles on in this vein until he informs me that we are approaching Plonkers.

‘Yeah. Diabolical name, isn’t it? I told her people would associate it with bonkers and she said that was the idea.’

The place is down Fulham way and there are a load of high class wheels parked outside the front door. All lean and hunched-up like greyhounds crapping in the gutter. Inside there is a long bar and lots of alcoves and small tables. There is sawdust on the floor and a few geezers wearing striped aprons who cater for the wine-drinking public. I have to admit that quite a few members of the grape-group are present and they make a marked contrast to the regulars at The Prospect of Doom. Some of them are even wearing suits and the whine of their upper class rabbit would drill holes in the side of a battleship.

If Rosie is glad to see us, the fact is not communicated by any movement of her features.

‘Oh, you’ve come,’ she says.

‘Only metaphysically,’ says Sid for some reason that I find hard to explain.

‘What can I offer you to drink?’ says Rosie, all posh-like.

‘I’ll have a glass of the house white,’ says Sid.

‘I’ll try the pillar box red,’ I say.

Once again Rosie’s features do not spring into smile position with whippet-like swiftness. ‘Don’t treat the place like the public bar at the Highwayman,’ she says coldly.

And to think I can remember when she used to believe that the sun set every time Sid fastened his pyjama cord. Some birds go off faster than last year’s turkey.

I turn away from this timely warning to anyone considering getting nuptially knotted and take a butche’s round the room. Imagine my surprise – go on, please do – when I see Daffers and the bloke she was with, sitting in one of the alcoves. I can recognise him by the black eye and the lump on the top of his nut – he went out of the window just after Rambling Jack Snorter.

Daffers recognises me the instant our mince-pies meet and I hear the familiar strains of the love theme from Tchaik’s RomeoandJuliet bashing a hole in my lug holes – with the last tinkling notes running away down the front of my Y-fronts. Surely fate must have thrown us together? Daffers clearly thinks so. She scampers to my side and informs me that Algie is on the point of passing out. A combination of booze and amateur brain surgery has reduced his already sub-standard sex appeal to vanishing point.

‘I think he ought to go home,’ she murmurs. ‘He’s not himself.’

I am tempted to suggest that any change must be an improvement but I control myself.

‘You have beautiful eyes,’ I say as if nothing in the world could make me think about anything else.

‘You mustn’t say that.’ Daffers squeezes my arm and her fate is sealed. Once birds start touching you it is but a question of minutes before their knickers are spoiling the cut of your jacket pocket.

‘Where does he live?’

‘Just round the corner, but he’s in no state to drive.’

‘I’ll drive.’ The words pop out of my mouth so fast that I think someone else must have said them.

‘Would you really?’

I knock back the red plonk so as not to offend Rosie and tell Sid that I am popping out for a few minutes.

‘Blimey, you’re a sucker for failure, aren’t you?’ he says. ‘Don’t hang about. I don’t want to stay here all night.’

I ignore him and help steer Algie out of the door. There is a glow in the east which makes me wonder if The Prospect of Doom is still burning. Algie has one of those little sports cars with about enough room in the back seat to lay a sausage roll lengthways and it is like fitting a broken umbrella into a shoe box to get him stowed away.

‘You should have gone in the back, really,’ I say. ‘Still, I’m glad you didn’t.’

Daffers pulls her skirt down towards her knees and runs her hand up my forearm. ‘Third on the left and I’ll give you instructions from there.’

‘Filthy Irish swine,’ drones Algie’s voice from the back seat. His head drops back and he begins to snore loudly.

‘Do you think we’re going to be able to get him out?’ murmurs my new friend. For some reason best known to herself her words accompany the pressure of dainty finger tips against my upper thigh.

‘No trouble,’ I breathe. ‘Now, tell me. How do you get this thing into gear?’

A few thousand fumbles later, we have arrived in a narrow cobbled mews which Daffers informs me is where Algie lives. I would have thought he could have done better than to kip over a garage but I don’t say anything. There is no point in hurting people’s feelings, is there? Not that Algie would speak up if I gave him a lantern slide lecture on the Kama Sutra. He is definitely out for the count. I, on the other hand, am now definitely out for something one letter shorter.

‘What are we going to do?’ Daffers’ concern sounds about as genuine as that of a bloke watching his mother-in-law drive over the side of a cliff.

‘I think it might be best to leave him here, don’t you?’ I gaze into the bird’s eyes and give a little shudder like a twig snatched away by a dangerous current over which it has no control.

‘Yes.’ The word urges her lips a few dangerous inches closer to mine and she shares my shiver.

‘Mmmm,’ I say. The noise savours the pleasures to come and the last ‘m’ accompanies the arrival of my north and south against Daffers’ soft, warm lips. At the same instant my right hand glides smoothly but purposefully between the lady’s thighs. She stiffens for a minute and then relaxes, sliding her arms round my neck.

‘Naughty,’ she says approvingly.

I don’t rush things but gently chew her lips whilst brushing my fingers against the fragile fabric guarding the entrance to her spasm chasm. At basement level percy is rolling out like a fireman’s hose and I have to effect a quick readjustment of my threads in order to rearrange the accommodation. Daffers is not slow to diagnose my problem and her thoughtful fingers arrive like a batch of flying doctors. As I hook my pinkies under the rim of her panties her own digits ease down my zipper and prepare to take percy for walkies.

We are now profitably involved in two areas of mutual interest and as our fingers glide and caress a certain urgency invades our actions. I slide my hand under Daffers’ back bumpers and with a little help from my friend tug her knicks towards an appointment with the carpet pile. For her part, Daffers is equally swift to expose my parts and percy soars upward like a twenty five pounder field gun released from its camouflage netting.

‘We mustn’t!’ gasps Daffers, eagerly. Even if your only experience of birds is helping old ladies across the road you soon get to realise that the hot flushes often coincide with the cold feet. They don’t mean it, of course, but a word of reassurance is always appreciated.

‘You’re beautiful,’ I breathe. Not the most original words in the English language but they pull more birds than a fleet of tugs. The steam is now running down the inside of the windows and it joins my impulsive lips in drowning any more of Daffers’ half hearted objections. I settle back into my seat and pull my passionate playmate towards me. With encouraging haste she scrambles across my knees and suddenly the car is a very small place. In the circumstances the best thing to do seems to be to make use of every inch of space and I slot into Daffers with a speed that would bring tears to the eyes of any woodwork master in the country. My hands close about her back buffers and we thump happily while I watch the misty outlines in the mews rise and fall in time with the car springs.

‘Heaven!’ breathes my new friend. ‘Oh, it’s good.’

I am in no mood to disagree with her and as the warm currents stirring through my loins race towards the rapids I sense that a small weight loss in the Y-front area is imminent if not even nearer.

‘What the Devil!’

That didn’t sound like me? And it’s not the kind of thing I say.

‘What the hell are you doing, Daffers?!’

With a sense of extreme irritation I realise that Algie has woken up. Some people have no feelings, do they? What a minute to choose. Just when I’m–

‘A-a-a-a-a-a-’

‘Daffers! You swine!’

‘-a-a-a-a-a-gh-!’

I stretch out an arm for the door handle and – oh dear! – stand by for another Lea Golden Rule: always leave the vehicle in gear when you’re having feels on wheels. That way you avoid releasing the hand brake and rolling backwards into all those dustbins. What a good job I had just put down a deposit, otherwise there might have been a nasty accident. Terrible to be snapped off in your prime.

‘Take that, you–!’

Algie is obviously feeling much stronger and I think it is probably safe to leave him and Daffers to sort things out. I open the door and fall into a sea of bottles – well, it is difficult to be light on your feet when your trousers are round your ankles and you have got some bloke thumping you in the earhole.

They do all right for themselves in this mews, I can tell you. The contents of all the dustbins scattered about would stock a boozer.

‘What the Devil–!?’

This time it is a geezer leaning out of a window. He is probably fretting because Algie’s sharp little motor car has dug itself into his front door. I am feeling decidedly fragile at knee level and am grateful that Plonkers is only just round the corner. Even a glass of red wine will go down a treat in my condition. I am but a few feet from the door when a human body emerges from it at an angle of forty-five degrees. This trajectory is maintained for about six feet and then the body descends sharply into the gutter. By the cringe, but it is a night for violence, isn’t it? It is amazing that anyone dares to step out for a drink these days. No doubt some undesirable scruff is being given the bum’s rush from Rosie’s posh clip joint.

In a manner of speaking I am correct. The stream of filthy lingo rising from the gutter could issue from only one cakehole.

‘What happened, Sid?’ I say, seizing the arm which is swinging back into punch-up position.

‘No bugger talks to my old woman like that and gets away with it.’ Sid surges towards the door but I manage to hold him back.

‘What did he say?’

‘He said he was going to liaise with her the weekend he got back from Amsterdam. Imagine that. He’s hardly through the door and he’s off with someone’s wife. I bet he’s got some lovely kiddies at home, too.’

‘Liaise isn’t a place, you berk,’ I say helpfully. ‘It means to get in touch with someone.’

‘Oh dear,’ says Sid. ‘Are you sure? No wonder Rosie got so worked up.’

‘What did you do?’

Sid looks down at the pavement. ‘I punched him about a bit. Nothing too strenuous. It was only when they all went for me that I had to defend myself.’ Before he can say anything else I hear the shrill note of an ambulance approaching at speed. I do not have to consult my crystal ball to know where it is going.

‘I think we’d better get out of here,’ I say. ‘I don’t reckon it’s one of our evenings. Not unless you fancy our chances of finding a load of talent in the local nick.’

Sid thinks hard for a minute. ‘It’s a nice publicity gimmick,’ he says slowly. Poor old Sid. If the Indians gave him beads he would be grateful.

‘Come on!’ I say. ‘Take me home, I’m knackered.’

‘You can stay with us,’ says Sid. ‘There’s loads of room and we can talk about the proposition in the morning.’

‘Is that going to be all right with Rosie?’

Sid says words to the effect that he is not going to be over-worried whether it is all right with Rosie or not. Furthermore, that if Rosie does not like it she knows what she can do with herself. It is obviously a subject that Sid enjoys talking about and he is still going strong when we get back to trendy Vauxhall.

‘Fancy a night cap?’ he says, advancing to the booze tray. I refuse and am directed to the third floor while my brother-in-law fixes himself another large scotch. He drinks too much, there is no doubt about it.

I am feeling dead knackered and the prospect of a bit of kip is very welcome. It has been a day rich in experience if not in achievement and I will have much to think about before the sand man dusts my mince pies with – knickers! For some reason the light in the room Sid directed me to is not working. Not to worry, I will do something about it in the morning.

I feel my way to the bed and start to strip off. I will have to sleep in the buff but that is no hardship. A bit chilly to start off with but – that’s funny. It seems quite warm as I slide a leg inside. Warm as the hand that grabs my action man kit.

‘Mr Noggett. You naughty man!’ The voice is full of East European promise and is not unknown to me.

‘I’m sorry,’ I squeak – and I mean squeak. ‘It’s not Mr Noggett. It’s me. I thought this was my room.’

‘Is my room. Everything in it is mine.’ Something about the way she says that makes me fear the worst – that and the way her mitt is still anchored to my hampton like it is a try your strength machine.

‘I’ll go.’

‘No! You come here for hanky wanky. You no need to be ashamed. It is always the same at the time of the potato harvest in my homeland.’ So that is where she gets her grip from. ‘The young men drink the Spudovitch and make merry with the maidens in the cow byres.’

‘Fascinating,’ I murmur. ‘I’ve often been tempted by those Winter Break holidays.’

‘Introduce me to your friend.’ Gretchen’s tone suggests that the time for cocktail party banter has passed.

‘I must go.’

‘No! My body will not be denied. Enter me!’

I would enter her for the Smithfield Show tomorrow but that is about all. Unfortunately she must have been taught unarmed combat at her mother’s knee and my left arm is forced up my back towards the nape of my neck before you can say Siberia.

‘Make frisky with me.’

If only I could remember what she looked like with the light on.

‘Maybe you like to make love with light on?’

‘No!’ Now it is my turn to bash the negatives. The sight of that face at a moment like this could put the kibosh on my sex life for keeps.

‘You like big titties?’ Gretchen pulls my face down onto her barrage balloon bosom and at that moment a flicker of lust passes through my action man kit. Never one of the smartest JTs in the business, my spam ram responds with animal urgency to the presence of sheer brute size.

‘Is good, no?’

The obvious answer to that question is no. However, an even more obvious answer has presented itself to me. The only way to get rid of the iron maiden is going to be to give in to her. Moving my head slightly so that I will be able to perform the vital movements whilst still alive, I hum ‘Rule Britannia’ under my breath and give brave, foolhardy percy his head. It may not be the end to a perfect day but at least it is the end.

Chapter Two (#u9230fa46-0ae0-540f-b51a-f3c527191deb)

In which an attempt is made to turn nephew, Jason Noggett, into a six-year-old Mick Jagger and Timmy shares a few idyllic moments with lonely Mrs Blenkinsop.

‘I’d forgotten she was in the spare room,’ says Sid.

‘Forgotten! Blooming heck! She could have killed me. When she fell asleep on top of me it took me ten minutes to crawl out.’

Sid waves my complaints away and continues to clean his earhole with a teaspoon.

‘Don’t worry about it. It’s all part of life’s rich tapioca, water that’s been passed under the bridge. Clear your mind and start thinking about Noggo Enterprises.’

‘Noggo Enterprises? What’s that?’

‘That’s us, Timmo. The company that’s going to promote all this talent under the Bella label.’

I politely refuse Gretchen’s offer of a second helping of porridge and put down my knife and fork – well, it is that lumpy you have to eat it with a knife and fork. At first I thought she had dropped a few spuds in it.

‘Why “Bella”?’ I say.

‘It’s an anadin of label,’ says Sid proudly.

‘I don’t see what that’s got to do with it. “Raft” is an anagram of “Fart” but I wouldn’t use it as a name for an air freshener.’

As usual, Sid is slow to admit that I have a point. ‘In the world of entertainment, presentation is half the battle. You’ve got to be slick and with it.’ Sid scrapes egg off the front of his shirt and licks the knife.

‘OK, Sid. You’re the boss. Where do we start?’

‘Right here in this house. You must have noticed that young Jason is not with us?’

‘He hasn’t run away from home?’ I try hard to keep a note of delirious gaiety out of my voice but it is not easy.

‘Do you know how old he is?’

I pretend to give the question a lot of thought. ‘Let me see. You and Rosie have been married for nearly six years, so he must be about six and a half.’

Sidney’s face darkens beneath the stubble. ‘Watch it, Timmo. Just because he was a bit premature, there’s no need to go jumping to conclusions.’

‘Premature? He was so early he was practically singing at the bleeding wedding.’

‘I won’t tell you again, Timothy. The child is a mature six and very advanced for his age, considering everything. I believe he can open up a whole new child market for us. I’ve sent him upstairs to get his clobber on.’

‘Surely he’s too young, Sid?’

‘Not these days he isn’t. The kids are the ones buying most of the records and the real mini-groovers don’t have anyone to identify with. If we can launch Jason we make our own market.’

When Sid talks like that I find it difficult to understand why everything we touch loses money. It seems such a good idea, doesn’t it?

‘Here I am, Dad.’

Blimey! The little basket looks like an explosion in a sequin factory. Faced with that kind of competition, Gary Glitter might as well get a job as a bank clerk.

‘Can he play that thing?’ I am referring to the kidney-shaped guitar with more sharp corners than a lorry-load of hair pins.

‘He can strum it a bit. The backing group will supply all the noise.’

‘Jason and the Golden Fleas,’ I say wittily.

‘Uncle Timmy, stupid,’ says the only kid in south London to be given a new set of nappies for his fourth birthday.

‘Sing him our song,’ encourages Sid.

I compose my features to receive the worst and, as usual, get it:

‘Stomp on your momma,

Stomp on your pa,

Stomp on everybody

With a yah, yah!’

‘It sounds better with his guitar plugged in,’ says Sid. My first instinct is to say that I would prefer it with the little bleeder’s finger jammed up a light socket but I control myself. Criticism is always better received if it is constructive.

‘It’s a bit violent, isn’t it?’ I ask.

Sid takes another swig of tea and wipes his mouth with the back of his hand.

‘Exactly, Timmo. That’s what we in the business call the difference factor. You take all the kids singing at the moment. Not only are they older than Jason but they’re all singing ballads. I see Jason as the first of the mini-bopper neo-decadents.’

‘Yerwhat?’

‘A seven-year-old Mick Jagger.’

It takes me a few moments to come to terms with this idea but when I see the pout on Jason’s thick little lips – not as thick as they would be if I had my way – I begin to get Sid’s drift.

‘Blimey!’

‘Yeah. You remember how the Stones made the Beatles look like a load of fairies? Well, Jason is going to make David Cassidy and Donny Osmond look like Hansel and Gretel.’

‘My best friend called Gretel,’ interrupts Gretchen who has appeared with a plate of charcoal doorsteps which might once have been bread. ‘You like her. She big girl.’

‘Belt up, shagnasty,’ says Sid, unkindly. ‘Why don’t you push off and put the porridge through the mincer?’

Gretchen must be doing badly at the Clapham Junction College of Commerce because she smiles happily and bears the vat of porridge away, humming what sounds like an old Slobovian sea shanty.

‘I think your mother must have taught her to cook,’ says Sid wearily. ‘She works on the principle that the quickest way to a man’s fart is through his stomach.’

‘Very funny, Sid,’ I say, humouring him. ‘But do you really think that the market is right for a hard rocking seven-year-old?’

‘He’ll come right through to the mini-market,’ says Sid. ‘He speaks their language. He is one of them. Not a manufactured product forced on them by their mums and dads.’

‘He’s a manufactured product forced on them by us.’

‘Exactly, Timmo. That’s the important difference. He’s a rallying standard in the battle against parental conformity. The leader of the mini-bopper rebellion.’

I look at Jason who has one finger wedged up his hooter and is stirring circles in the sugar bowl with another and ask myself: can Sid be right this time? It is obvious that he has been getting ideas from the magazines in Doctor Naipaul’s waiting room but that has never been a guarantee of success in the past.

‘I’m still sceptical, Sid,’ I say.

‘Well, you’d better go and see a doctor,’ says Sid, screwing up his eyes in distaste. ‘Don’t talk about it at the breakfast table. It puts me right off my kipper.’

‘No, Sid,’ I say wearily. ‘I meant that I’m not convinced you’re right.’

Sid stands up, ‘You don’t have to take my word for it. I’ve entered Jason for the vicar’s kiddies talent contest. You wait till you see what he does to them down there. It’ll be an ideal test run. After that it’s the big time. Eh, Show Stopper?’

Jason tries to nod but his finger is still up his hooter and he nearly does himself a nasty injury.

‘What are you going to call him, Sid?’

Sidney switches on his ‘I’m so clever I might kill myself’ expression.

‘Plain Jason,’ he says.

‘I don’t get it,’ I say. ‘I mean, he is plain but do you want to remind every–’

‘If you weren’t so stupid I would think you were taking the piss,’ says Sid.

‘Uncle Timmy, very stupid,’ says Jason.

‘What I meant–’ Sid hits every word like it is a nail. ‘What I meant is that we are going to call him Jason. Jason all by itself. Jason nothing. It’s his real name, see? Very natural, very genuine. It’s a wonderful gimmick.’

‘I prefer Jason Nothing,’ I say.

Sid controls himself with difficulty. ‘You keep your preferences to yourself and help Jason off with his suit. I’m going to see about a group that could be very big. If I’m not back by four you’ll have to take Jason down to the church hall. And check that the sockets fit the plug on his guitar. They’ve got some terrible old stuff down there.’

Marvellous, isn’t it? With all my looks and personality I end up as dresser to a six-year-old kid whose nose runs faster than a Derby winner. I would not mind so much if Jason was not such an uncooperative little basket. He refuses to change at the church hall and throws a paddy because two of his sequins fall off coming down the stairs. Rosie is out on business so I have to sew the bleeding things on. I have just finished doing this when Jason wants to do potty and I find out I have sewn his trousers to his pants. This piece of information costs me another five sequins and twenty minutes during which my lips are jammed together tighter than a novice nun’s knees at an Irish funeral party.

By the time I have finished it is a race against time to get to the church hall before the Vicar’s frolic starts.

‘Uncle Timmy catch it when my dadda gets back,’ says Jason happily.

‘Little Jason catch a bunch of fives up his bracket if he doesn’t button his lip,’ I hiss. ‘Now, get a move on or we’re going to miss the bus.’

You would not believe it, but the little basket has the gall to throw a tantrum because he is not travelling by chauffeur-driven Rolls. God knows what Sidney has been telling him. I feel a right berk standing in the bus queue with Jason in his ridiculous clobber. He makes a toreador look like one of those skinheads who wanders down Oxford Street chanting ‘Hairy Krisnan’.

The bus conductor is not over-thrilled to see him either.

‘You going to bring the organ on as well, mate?’ he says to me. ‘You can take him on top if you like. There’s an old girl up there with a bunch of bananas.’

I ignore these crude attempts at humour and try to avoid the other passengers’ eyes as I cradle Jason’s guitar on my lap. He may be the answer to every five-year-old’s prayers but he is not doing much for the senior citizens huddled around me. They watch him like snakes being offered a glass rat for dinner. The Vicar does not exactly cream his cassock either.

‘I’m afraid the fancy dress party was last week,’ he says, nervously.

‘Belt him, Uncle Timmy,’ says Jason in a loud whisper.

‘This talented little chap is taking part in your contest, Vicar,’ I say evenly. ‘I’m sorry we’re a few minutes late.’

‘Jason Noggett, is it?’ says the Vic, going down his list. ‘I don’t think I’ve seen you or your wife since the wedding.’

‘I’m not married,’ I say.

The Fire Escape’s face clouds over. ‘Oh dear. I’m afraid that only those relationships that have been sanctified by the Holy Sacrament can offer up their fruit for inclusion in our talent contest.’

For a moment I think he is talking about a vegetable show and then I get his drift. ‘I’m the boy’s uncle,’ I say.

The Vicar looks much happier. ‘Of course. How silly of me. It’s so easy to jump to conclusions these days, isn’t it?’

‘How long before he goes on?’ I ask. I never feel comfortable talking to holy men. I think it goes back to when I was a kiddy and could not understand why they were dressed up as birds.

‘He’ll have to go on right at the end,’ says the Vic. ‘I’ve made out a list and I can’t change it now.’

‘Top of the bill,’ says Junior Monster, showing the first signs of pleasure he has evinced all afternoon.

‘It’s all harmless fun,’ says the man of God, realising that he has got ‘star or bust’ material on his hands. ‘Nothing too serious. I got the idea from one of those television programmes.’

I am getting ideas myself, but from a different quarter. One of the ladies present, presumably a mum, is definitely in the knock-out class. Slim, but with nice knockers and a wistful expression that makes me want to defend her against dragons and people like me. She has her arm resting on the shoulder of a kid wearing specs and long velvet shorts. The kid looks terrified, maybe because he is scared that his cello is going to fall on top of him. He holds his bow like a character in a fairy story defending himself against a giant spider. Poor little sod. He has obviously got no chance in the competition and is scared to wetsville about going on the stage.

I catch mum’s eye just as the Vic, hurries off to investigate a reported stabbing in the ladies – I noticed a geezer frisking the kids for weapons as I came through the door.

‘Have a shufti at the opposition, Jason boy,’ I say giving my tiny charge a gentle push in the direction of the stage, ‘– and don’t use language like that in the church hall!’ It may have been a silly place to leave a pile of hassocks but there was no need for him to say that. I don’t know where the little bastard gets it from.

‘Kids today!’ I say in my best ‘over the garden wall’ manner. ‘Little devils, aren’t they?’

‘There’s a lot of high spirits about,’ says Pablo Casals’s mother. She has one of those posh voices that suggests she lives in one of the houses facing Clapham Common. We live in a house that overlooks Clapham Common – completely.

‘When’s your boy going on?’ I ask.

‘Right at the end. It’s very nerveracking, isn’t it, William?’ William gulps and nods miserably. It’s a shame really. She should never have brought him. I know these upper class birds. They reckon they ought to get involved in the community and go around forming committees and parent teachers’ associations. Their kids go to state schools and their husbands hand out glasses of sherry and talk about community spirit. When the value of their house has trebled they sell up, move to Hampstead and send the kids to public school. They do a nice tea, though.

There is a burst of jeers and whistles from behind a curtain and a kid runs past wearing a bow tie and a top hat. He is in tears and is closely followed by a mother figure.

‘They did what with your balls?’ I hear her saying as they disappear from sight.

I take a peep through the curtain and – blimey! – I am glad I don’t have to go out there. They make the average Crackerjack audience look like Parkhurst lifers. I can hardly see beyond the first three rows for the pall of smoke and the kids are hopping about like a flea circus on acid. The stage is littered with orange peel and coke cans and the Vic is waving his arms about like it is the first heat of a semaphore contest.

‘Children, I appeal to you!’ he shrieks.

‘No you don’t, Baldy! Push off!’

‘What a load of rubbish!’

‘Why are we waiting!’

I step back from the curtain and shoot a quick glance at Jason – I would prefer to shoot a bullet but you can’t have everything you want in life. If the little bleeder can’t get this lot going he might as well jack it in immediately. I hope the Vic has the hall insured.

‘William Blenkinsop, William Blenkinsop! If I’d have known Miss Trimble’s mother was having her varicose veins done today I’d have put the whole thing off for a week.’

The poor old Vic is clearly going to pieces faster than flaky cod. William Blenkinsop has turned the colour of cold suet and is led out onto the stage by his mother carrying a chair. A chorus of wolf whistles suggests that some of the kiddies present have very mature tastes. I even think I hear a shout of ‘get ’em orf!’ but it must be my imagination.

‘What is first prize?’ Jason’s evil little eyes glint with anticipation. He obviously reckons it is all over bar the shouting.

‘Quite an ordeal for the boy, Mrs Blenkinsop,’ I say in my best Dixon of Dock Green voice.

‘Yes. I wish – perhaps I shouldn’t – oh, I don’t know.’ She leans forward nervously and I gaze sympathetically at the soft swellings in her fisherman-knit sweater. I wonder if I slid my arms round her and – no, it probably wouldn’t. People have such different ideas when it comes to offering comfort.

‘William Blenkinsop is going to play–’ There is an ugly pause while it occurs to everyone that the Vic has no idea what W.B. is going to play.

‘With his willy!’ shouts a child with a big future on late night chat shows. I can feel the glow of the Vic's cheeks from where I am standing. He mouths desperately into the wings.

‘Bach.’

‘Woof, woof!’ bays the audience.

Mrs Blenkinsop stiffens beside me and for a moment I think she is going to dash on the stage and yank William off. I have not heard a worse reception since Dad played us the last wireless he nicked from the lost property office.

‘Poor kid,’ I breathe as William licks his lips and prepares to play the first few chords. His eyes are closed and it is only the movement of the bow that tells us he is wanging away. The row is so great you can’t hear anything. Then, slowly, the music starts coming through. I don’t know a cello from a pregnant fiddle but it is obvious that the kid knows how to play the thing. The audience stop giving him the bird and start to listen. By the time the last note has wafted away into the rafters you could hear a pin drop. There is a moment’s pause and then lughole-shattering applause.

The only person not clapping is Jason. He looks about as happy as Ted Heath at a miners’ rally.

Out on the stage, William Blenkinsop bows stiffly and walks towards his highly chuffed mum.

‘OK Super Star,’ I say to Jason. ‘Now’s your chance to make history. Get out there and sock it to them.’ I take a last look at him and, of course, the stupid little basket has forgotten to do up his zipper. I give it a savage tug and – oh dear! The whole thing comes away in my hand.

‘What you doing!?’ shrieks Jason.

‘It doesn’t matter. You’re all right. Get out there. I’ll plug you in.’ His trousers are very tight and nobody would recognise his willy wonker if he painted it in day glo paint.

The Vic bustles up, looking a shade happier. ‘Jason Noggett, isn’t it?’

‘Just Jason.’

‘And he’s doing an impression of someone?’

‘No, he’s being himself,’ I say. ‘He’s going to sing an original composition entitled “Stomp on your momma”.’

The Vic does not look as if this is the best news he has had since the second coming but nods and shambles onto the stage with his silent lips rehearsing the words to come. We follow him.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию (https://www.litres.ru/timothy-lea/confessions-of-a-pop-star/) на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Timothy Lea

Pop music, screaming fans, incredible tours – being a Pop Star certainly has rewards…Available for the first time in eBook, the classic sex comedy from the 70s.Timmy Lea needs a new job, and Noggo Enterprises promise to make him a star.But can he navigate his brother-in-law Sid? Their certainly seem to be lots of adoring, receptive fans, who all want a piece of him – in bars, in cars, and in seedy hotel rooms.Also Available in the Confessions… series:CONFESSIONS OF A WINDOW CLEANERCONFESSIONS OF A LONG DISTANCE LORRY DRIVERCONFESSIONS OF A TRAVELLING SALESMAN

Confessions of a Pop Star

BY TIMOTHY LEA

Contents

Cover (#uca1f6db8-8e13-57b2-907d-6626e8a4458d)

Title Page (#u2bbaf576-f3ab-5ca1-9431-1bce8767fcf3)

Publisher’s Notes

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Also available in the CONFESSIONS series

About the Author

Also by Timothy Lea & Rosie Dixon

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher

Publisher’s Note (#u9230fa46-0ae0-540f-b51a-f3c527191deb)

The Confessions series of novels were written in the 1970s and some of the content may not be as politically correct as we might expect of material written today. We have, however, published these ebook editions without any changes to preserve the integrity of the original books. These are word for word how they first appeared.

Chapter One (#u9230fa46-0ae0-540f-b51a-f3c527191deb)

In which a talent spotting trip to the East End with brother-in-law, Sid, involves Timmy in an unseemly fracas and two close brushes with the opposite sex.

‘Gordon Bennett!’ says Dad. ‘Most people can get out of the nick easier than the army. “Dishonourable Discharge.” Sounds like what we used to find on the front of your pyjamas.’

‘Dad, please!’ I mean, that kind of remark is so uncalled for. Anyhow, I never had a pair of pyjamas when I was going steady with the five-fingered widow.

‘This latest disgrace has dropped us right in it with the neighbours. I don’t know where to put my face.’

‘Why don’t you try some of the places Sid has been suggesting all these years?’ It is sad, but Dad always brings out the worst in me.

‘You leave your sponging brother-in-law out of this. Just consider what you’ve achieved in the last five years. You’ve broken your mother’s heart and now you’ve damn near done for mine. In the nick twice and God knows how many jobs you’ve had.’

‘The first time was only reform school, Dad.’

‘That’s shredded in the mists of antiquity, that is. Why can’t you be like your sister? A nice home, two lovely kiddies. She’s done all right for herself.’

‘I couldn’t find the right bloke to settle down with, Dad.’

‘I don’t expect it’s for want of trying, though. That’s the one thing we haven’t had from you, isn’t it? I’m waiting for you to turn into a nancy boy. That’ll be the final nail in my coffin.’

‘I’ve started a whip round for the hammer, Dad.’

As might be expected, Dad is not slow to take umbrage at this remark.

‘That’s nice, isn’t it? Bleeding nice. That really puts the kibosh on it, that does. You sacrifice your whole life to your kids and what do you get? Bleeding little basket wants to see you under the sod.’

‘One on top of the other, Dad.’

Dad steams out of sight and I consider what an ugly, weasel-faced old git he is. It is amazing to think that he could have produced something as overpoweringly lovely as myself. Sometimes I wonder if he actually did have a hand in it – or something more intimate. I have always found it disgusting to think of my Mum and Dad on the job but the thought of some invisible third-party – a prince or something like that – giving Mum one behind Battersea Town Hall seems much more favourite. The arse is always cleaner on the other side of the partition, if you know what I mean.

Of course, to be fair, you can understand Dad being a bit narked. When I was conned into signing on as a ‘Professional’ for nine years, he must have thought that he could fill every inch of my bedroom with nicked stuff from the lost-property office where he works. I use the word ‘work’ in its loosest sense. Dad had to be carried into the nearest boozer when someone in his bus queue mentioned overtime. When Dad thought he had got rid of me, he reckoned without Sid’s ability to put the mockers on anything he comes into contact with. I will never forget the sight of Sid’s nuclear warhead drooping towards submarine level while the colonel’s lady shouted for action and all those Yanks with gaiters halfway up their legs bristled in the doorway. It is the nearest we have ever come to causing World War III. She was a funny woman, that one. Very strange. There can’t be many birds who fancy a bit of in and out under the shadow of the ultimate deterrent – still, I expect you read all about it in ConfessionsofaPrivateSoldier so I won’t go on. (Of course, if you did not read about it, there is nothing to stop you nipping round the corner and having a word with your friendly local newsagent. If you ask him nicely he might be able to find you a copy – to say nothing much about the other titles in the series. For instance, there is – ‘Belt up and get on with it!’ Ed. All right, all right! I’ve got to live, haven’t I. Blimey, these blokes think you can nosh carbon paper. I am not surprised that LesMiserables packed it in after one book.)

Anyway, getting back to the present. There I am at 16, Scraggs Lane, ancestral home of the Leas since times immemorial after an unproductive brush with HM Forces. It might have done Mark Phillips a bit of good but I did not as much as catch sight of a corgi’s greeting card the whole time I was in the Loamshires. Ridiculous when you consider how many Walls sausages the family must have eaten over the years. And talking of food, here comes my Mum, that commodity’s greatest natural enemy. The only woman to have burned water.

‘Stop going on, Dad,’ she says. ‘Tea’s on the table. I’ve got some nice fester cream rice for sweet.’

‘You mean, Vesta Cream Rice, Mum. “Fester” means to turn rotten.’

‘You want to taste it before you start telling your mother what she means,’ snorts Dad. ‘It doesn’t take a lot of prisoners, that stuff, I can tell you.’ Mum may be a diabolical cook but her heart is in the right place – and that saves an awful lot of trouble when you go for a medical checkup, I can tell you. It also means that she is always glad to see me home whatever I have done. She has even tried to spell out ‘WELCOME’ in the alphabet soup.

‘It’s funny,’ she says, gazing at me over the curling beef-burgers. ‘You look such a wholesome boy.’

Dad snorts. ‘I expect Jack the Ripper looked bleeding wholesome and all. Don’t start making excuses for him, mother. He’s never going to change. I’ve given up hope for him.’

‘Have you thought about what you’re going to do, now, dear?’ says Mum, absentmindedly straining the cabbage on to the beefburgers – at least it takes the curl out of them.

‘Sid’s got an idea about going into the entertainment business. I’m having a talk with him tonight.’

‘ “Entertainment?” But you don’t do anything.’

‘You can say that again,’ sneers Dad.

‘I know how you got that job at the lost property office,’ I say. ‘Someone handed you in, did they?’

‘Watch it, Smart Alec!’

‘Stop it, both of you. You know I can’t stand scenes. I still don’t see what Timmy is going to do. Sid doesn’t play anything, does he?’

‘Sidney Noggett has been on the fiddle for years,’ says Dad wittily. ‘That’s the only way you get anywhere, these days. A decent working-class man with a set of principles might as well stay at home.’

‘You do stay at home most of the time, Dad.’

‘It’s my back, isn’t it? There’s no cause to mock the afflicted. If me and a few more like me didn’t have our aches and pains you might be feeling the Nazi jackboot across the back of your neck.’

Dad does tend to over-dramatise a bit for a bloke who spent most of World War II fire watching. In fact I have known him turn off Dad’s Army because he found it too harrowing. Still, he is very sensitive on the subject and since my present standing in the family is one of grovelling I should be advised to lay off.

‘Sorry, Dad.’ The words are more difficult to form than the Bermondsey branch of the Ted Heath fan club.

‘I should bleeding think so. Young people today don’t know the meaning of the word patriotism. Look at us. Knocked out of the World Cup by a load of Polaks. The Krauts going mad in Munich. It’s a bleeding national disgrace.’

‘Come on, Dad. When your mate, Stanley Matthews, was playing we were beaten by the Yanks.’

Dad does not like this. ‘Sir Stanley Matthews if you don’t mind, Sonny Jim. That was the atmospheric conditions, wasn’t it? They made them play up the side of a mountain, didn’t they? Our lads weren’t used to it. I don’t call that football.’

‘Do give over, Dad,’ says Mum. ‘How do you like the beefburgers?’

‘I don’t reckon them boiled, I can tell you that.’ Dad did not see Mum straining the cabbage over them.

‘Just as you like, dear. I thought it might make a change.’

Mum does not bat an eyelid. ‘Eat up, Timmy. Your rice is all ready.’

Already ruined, I can see that. Once it starts making a bolt for it over the side of the saucepan you can reckon that it has given up the ghost.

‘I don’t know if I can manage it, Mum,’ I say, patting my stomach in a way that I hope suggests satisfaction with the excellent fare that has already been provided.

‘Go on. I know you can find room for it. I’ll put some golden syrup on it like I used to when you were a little boy. You remember how he used to love hot, sticky things when he was a kiddy, Dad?’

‘Yeah.’ Dad’s face adapts a thoughtful expression and I can sense his disgusting mind working on some tasteless descent into vulgarity.

‘Just a little bit, Mum,’ I say hurriedly, ‘I think I put on some weight in the army.’

‘I was thinking how thin you looked.’ Mum thumps down an enormous helping of what looks like petrified frog’s spawn. I do wish she would not use the spoon with which she dishes out the beefburgers. ‘There you are. Rice is the stable diet of the Chinese, you know.’

‘This lot looks as if it’s seen the inside of a stable and all,’ complains Dad. ‘Gordon Bennett! How do you manage to get it like that?’

‘I did what it said on the side of the tin,’ says Mum, patiently reading from the label. ‘ “Brown and crisp on the outside, moist and tender in the middle.” ’

Dad claps his hand to his head. ‘Gawd, give me strength! That’s the steak-pie tin, isn’t it? Can’t you even read from the right bleeding labels?’

‘Oh dear. It must be my glasses,’ says Mum.

‘Yeah, you want to stop filling them to the brim all the time,’ snaps Dad.

‘It wouldn’t be a surprise if I did turn to drink, the way you go on at me,’ sniffs Mum. ‘If the food isn’t good enough for you, you’d better give me some more house-keeping money.’

‘I daren’t do that,’ says Dad. ‘All you’d do is buy bigger tins.’

‘At least the print on the labels would be larger, Dad,’ I say helpfully.

‘Don’t you turn against me, now,’ sobs Mum. ‘I try and do you something nice when you come home and this is all the thanks I get.’

‘See what you’ve done now?’ snarls Dad. ‘You’ve made your mother cry. As soon as you’re through the door you’re spreading misery and unhappiness. If what you get here isn’t good enough for you –’

His voice drones on but it is a track from an LP I have heard a million times and the words disappear like raindrops into snow. I am meeting Sid round at his Vauxhall pad and I am not sorry when the time comes to steal away with Dad’s voice melting in my ear and a fistful of Rennies belting down to put out the fire in my belly. I am also looking forward to seeing sister Rosie again. When Sid last talked about her she had started up a couple of boutiques and was doing all right for herself. Ever since her little brush with Ricci Volare on the Isla de Amor she has been a different woman from the one that used to hover in front of Sid like the pooch on the old HMV label. I feel sorry for Sid. It can’t be nice for a bloke to see his wife doing something on her own – especially when she starts doing better than he is. Ever since the Cromby Hotel, Sid has been marking time if not actually going backwards while Rosie has been coming up like super-charged yeast. How will I find the girl who was voted Clapham’s ‘Miss Available’ in the balmy days of 1966?

The short answer is – thinner. Rosie’s tits seem to have evaporated and the skin is stretched over her face like the paper on the framework of a model aeroplane. She has also done something with her eyebrows – like got rid of them – and her barnet is closer to her nut that I can ever remember it.

‘Got to go out, Timmy love,’ she says, kissing me on the cheek. ‘Sidney will give you a drink. Must fly. See you again.’

Her voice is different, too. Not exactly posh, but sharper. It carries more muscle, somehow.

Sid looks relieved when she has pushed off. ‘What’s your poison?’ he says.

I am a bit disappointed with the surroundings. I had been expecting signs of loot, but they don’t even have a cocktail cabinet. The booze is laid out on a tray and that rests on a table which is definitely on its last legs. Peppered with worm holes and dead old-fashioned looking. Most of the stuff they have got must have come from a junk shop though the carpet is nice. Probably took up all their cash.

‘I’ll have a light ale, since you’re asking,’ I say.

Sid looks uncomfortable. ‘We don’t have any light ale. There might be some lager in the fridge.’