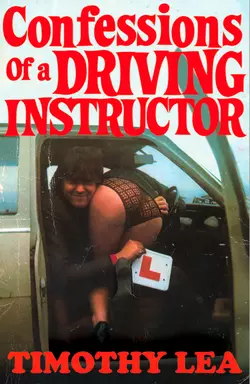

Confessions of a Driving Instructor

Timothy Lea

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Эротические романы

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 191.96 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 28.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: The classic sex comedy of the 70s, available for the first time in eBook.The classic sex comedy of the 70s, available for the first time in eBook.Scream if you want to go faster! Who knew learning to drive to could be this exciting? Certainly not Timothy Lea and his brother-in-law Sid, who’re a little overwhelmed by all the top beauties who suddenly want a play behind the wheel…Also Available in the Confessions… series:CONFESSIONS FROM A HOLIDAY CAMPCONFESSIONS OF AN ICE CREAM MANCONFESSIONS FROM THE CLINKand many more!