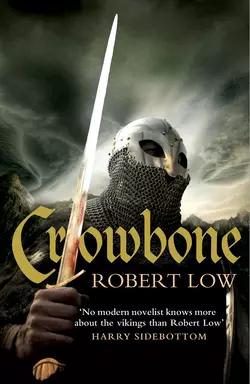

Crowbone

Robert Low

The long awaited return to Robert Low’s Oathsworn seriesIsland of Mann, 979AD. A monk lies dying with a sworn secret he must pass onto Crowbone, the true heir to Norway’s throne, before he breathes his last. The monk’s words will decide the fate of a kingdom.But once the secret is revealed, Crowbone’s long-time enemy, Gunnhild, the Witch Mother of Kings, threatens his path to the crown and will stop at nothing to prevent him from attaining his royal destiny. Crowbone and his men must survive an unforgiving journey and face their sworn rival. It is a quest that will test the very bonds that tie the Oathsworn together.

ROBERT LOW

Crowbone

To my wife, Kate,

who keeps my eyes on the real prize

In the hilt is fame.

In the haft is courage,

In the edge is fear.

Lay of Helgi Hjörvarðsson

Table of Contents

Title Page (#uf2ec4d0d-283f-5681-bbcb-e9c350959b0d)

Dedication (#u6c409563-56b8-51c3-ada8-fcf0cec77c12)

Epigraph (#u2247bea2-0ab4-572e-a70c-9b923638ca23)

Map (#uaf3857b0-abcc-580a-93fc-95917caf4e72)

Prologue (#u2e4c6f4a-f994-5cb7-9487-36f899dd73b6)

One (#u3e6787ac-37ca-5717-9431-bce19a692dae)

Two (#ua8784b37-24e7-5edf-966e-3f31396863f5)

Three (#u10c6dc80-96a6-57b6-910e-0f7b4efc663d)

Four (#u38bdcfae-438a-57b3-93f8-c213032cf798)

Five (#litres_trial_promo)

Six (#litres_trial_promo)

Seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Ten (#litres_trial_promo)

Eleven (#litres_trial_promo)

Twelve (#litres_trial_promo)

Thirteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Fourteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Epilogue (#litres_trial_promo)

Historical Note (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Also by Robert Low (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

PROLOGUE

Finnmark, A.D. 981

THEIR skin was already slack and waxen yet unsettling, with meltwater frozen from their final cooling beaded like new sweat. Black and orpiment bruising, red wounds gaping like lipless mouths, black blood thick as porridge crusting in the cold.

One face seemed to be looking at everyone who looked at it, a bewildered question frozen in the glassed eyes. His knuckles were clenched so tight on his belly that the rough pelt he wore oozed between fingers clamped on either side of the great gash, as if trying to force it shut on the blue snakes coiling from it. His hair was wild and uncombed and his nose needed wiping.

Too late for all of that, Crowbone was thinking.

They were tough, these dark little Sami from the snow hills, feared even by the Norse from Gjesvaer, who hunted whale and walrus and ice bears over the northern floes. They knew that the Sami could stalk a man and he would never know it until the bone tip of an arrow came out of his heart.

Even in a stand-up fight they are killing us, Crowbone thought, carving us like chips off a great tree. Men lay not far off, arms folded on their breasts and faces covered by cloaks. Men of skill and wit, gone from boasts and laughter to sacks of clothing, laid out like fresh-cut logs and just as stiff in the cold.

As for the Sami, they had now fought these mountain hunters too many times, but this was the first time they had seen so many of them dead in the one place. The crew moved among them silently, save for a muttered growl here and there, peered and prodded, knelt now and then to search in the blood and splintered bone. They were trying hard to ignore the strangeness of these beast-masked warriors and all the old fear-tales of Sami wizards.

It was Murrough, cleaning the great hook-bearded Dal Cais axe with one of their skin masks, who gave voice to all their fears, as he squinted at one lolling body and nudged it with his foot.

‘Sure,’ he said, ‘and I killed this one yesterday, so I did.’

ONE

Island of Mann, A.D. 979

THREE sheltered in the fish-reeked dim of the keeill, cramped up and feeling the cold seep into their bones – but only one of them did not care, for he was dying. Though truth was, Drostan thought, glancing sideways at the red-glowed beak-face of the Brother who lived here, perhaps this priest cares even less than the dying.

‘I am done, brother,’ said Sueno and the husked whisper of him jerked Drostan back to where his friend and brother in Christ lay, sweat sheening his face in the faint glow from the fish-oil light.

‘Nonsense,’ Drostan lied. ‘When the storm clears tomorrow we will go down to the church at Holmtun and get help there.’

‘He will never get there,’ said the priest, voice harsh as the crow dark itself and bringing Drostan angrily round.

‘Whisht, you – have you so little Christian charity in you?’

There was a gurgle, which might have been a laugh or a curse, and suddenly the hawk-face was thrust close, so close that Drostan bent backwards away from it. It was not a comfort, that face. It had greasy iron tangles of hair round it, was leached of moisture so that it loomed like a cracked desert in the dark, all planes and shadows; the jaws clapped in around the few teeth in the mouth, which made black runestones when he spoke.

‘I lost it,’ he mushed, then his glittering priest eyes seemed to glass over and he rose a little and moved away to tend the poor fire, bent-backed, a rolling gait with a bad limp.

‘I lost it,’ he repeated, shaking his head. ‘Out on the great white. It lies there, prey to wolves and foxes and the skin-wearing heathen trolls – but no, God will keep it safe. I will find it again. God will keep it safe.’

Shaken, Drostan gathered himself like a raggled cloak. He knew of this priest only by hearsay and what he had heard had not been good. Touched, they said. A pole-sitter who fell off, one or two claimed with vicious humour. Foreign. This last Drostan now knew for himself, for the man’s harsh voice was veined with oddness.

‘God grant you find it soon and peace with it, brother,’ Drostan intoned piously, through his gritted teeth.

The hawk-face turned.

‘I am no brother of yours, Culdee,’ he said, his voice a sneer. ‘I am from Hammaburg. I am a true follower of the true church. I am monk and priest both.’

‘I am merely a humble anchorite of the Cele Dei, as is the poor soul here. Yet here we all are,’ answered Drostan, irritated. ‘Brother.’

The rain hissed on the stone walls, driving damp air in to swirl the scent of wrack round in the fish-oil reek. The priest from Hammaburg looked left, right and then up, as if seeking God in the low roof; then he smiled his black-rotted smile.

‘It is not a large hall,’ he admitted, ‘but it serves me for the while.’

‘If you are not one of us,’ Drostan persisted angrily while trying to make Sueno more comfortable against the chill, ‘why are you here in this place?’

He sat back and waved a hand that took in the entire keeill with it, almost grazing the cold stone of the rough walls. A square the width of two and half tall men, with a roof barely high enough to stand up in. It was what passed for a chapel in the high lands of Mann, and Drostan and Sueno each had their own. They brought the word of God from the Cele Dei – the Culdee – church of the islands to any who flocked to listen. They were cenobites, members of a monastic community who had gone out in the world and become lonely anchorites.

But this monk was a real priest from Hammaburg, a clerk regular who could preach, administer sacrament and educate others, yet was also religious in the strictest sense of the word, professing solemn vows and the solitary contemplation of God. It stung Drostan that this strange cleric claimed to be the united perfection of the religious condition – and did not share the same beliefs as the Cele Dei, nor seem to possess any Christian charity.

Drostan swallowed the bitter bile of it, flavoured with the harsh knowledge that the priest was right and Sueno was dying. He offered a silent apology to God for the sin of pride.

‘I wait for a sign,’ the Hammaburg priest said, after a long silence. ‘I offended God and yet I know He is not done with me. I wait for a sign.’

He shifted a little to ease himself and Drostan’s eyes fell to the priest’s foot, which had no shoe or sandal on it because, he saw, none would have fitted it. Half of it was gone; no toes at all and puckered flesh to the instep. It would be a painful thing to walk on that without aid of stick or crutch and Drostan realised then that this was part of the strange priest’s penance while he waited for a sign.

‘How did you offend God?’ he asked, only half interested, his mind on Sueno’s suffering in the cold.

There was silence for a moment, then the priest stirred as if from some dream.

‘I lost it,’ he said simply. ‘I had it in my care and lost it.’

‘Christian charity?’ Drostan asked without looking up, so that he missed the sharp glitter of anger sparking in the priest’s eyes, followed by that same dulling, as if the bright sea had been washed by a cloud.

‘That I lost long since. The Danes tore that from me. I had it and I lost it.’

Drostan forgot Sueno, stared at the hawk-faced cleric for a long moment.

‘The Danes?’ he repeated, then crossed himself. ‘Bless this weather, brother, that keeps the Dyfflin Danes from us.’

The Hammaburg priest was suddenly brisk and attentive to the fire, so that it flared briefly, before the damp wood fought back and reduced it once more to a mean affair of woodsmoke reek and flicker.

‘I had it, out on the steppes of Gardariki in the east,’ he went on, speaking to the dark. ‘I lost it. It lies there, waiting – and I wait for a sign from God, who will tell me that He considers me penance-paid for my failure and now worthy to retrieve it. That and where it is.’

Drostan was millstoned by this. He had heard of Gardariki, the lands of the Rus Slavs, but only as a vague name for somewhere unimaginably far away, far enough to be almost a legend – yet here was someone who had been there. Or claimed it; the hermit-monk of this place, Drostan had been told, was head-sick.

He decided to keep to himself the wind-swirl of thoughts about his journey here, half carrying Sueno, whom he had visited and found sick, so resolving to take him down to the church where he could be made comfortable; he would say nothing of how God had brought them here, about the storm that had broken on them. It was then God sent the guiding light that had led them here, to a place so thick with holy mystery they had trouble breathing.

The cynical side to Drostan, all the same, whispered that it was the fish oil and woodsmoke reek that made breathing hard. He smiled in the dark; the cynical thought was Sueno’s doing, for until they had found themselves only a few miles of whin and gorse apart, each had been alone and Drostan had never questioned his faith.

He had discovered doubt and questioning as soon as he and Sueno had started in to speaking, for that seemed to be the older monk’s way. For all that he wondered why Sueno had taken to the Culdee life up there on the lonely, wind-moaning hills, Drostan had never resented the meeting.

There was silence for a long time, while the rain whispered and the wind moaned and whistled through the badly-daubed walls. He knew the Hammaburg priest was right and Sueno, recalcitrant old monk that he was, was about to step before the Lord and be judged. He prayed silently for God’s mercy on his friend.

The priest from Hammaburg sat and brooded, aware that he had said too much and not enough, for it had been a time since he had spoken with folk and even now he was not sure that the two Culdees were quite real.

There had been an eyeblink of strangeness when the two had stumbled in on him out of the rain and wind and it had nothing to do with their actual arrival – he had grown used to speaking with phantoms. Some of them were, he knew, long dead – Starkad, who had chased him all down the rivers of Gardariki and into the Holy Land itself until his own kind had slaughtered him; Einar the Black, leader of the Oathsworn and a man the Hammaburg priest hated enough to want to resurrect for the joy of watching him die again; Orm, the new leader and equally foul in the eyes of God.

No. The strangeness had come when the one called Drostan had announced himself, expecting a name in return. It took the priest from Hammaburg by surprise when he could not at once remember his own. Fear, too. Such a thing should not have been lost, like so many other things. Christian charity. Long lost to the Danes of the Oathsworn out on the Great White where the Holy Lance still lay among fox turds and steppe grasses. At least he hoped it was, that God was keeping it safe for the time it could be retrieved.

By me, he thought. Martin. He muttered it to himself through the stumps of his festering teeth. My name is Martin. My name is pain.

Towards dawn, Sueno woke up and his coughing snapped the other two out of sleep. Drostan felt a claw hand on his forearm and Sueno drew himself up.

‘I am done,’ he said, and this time Drostan said nothing, so that Sueno nodded, satisfied.

‘Good,’ he said, between wheezing. ‘Now you will listen more closely, for these are the words of a dying man.’

‘Brother, I am a mere monk. I cannot hear your Confession. There is a proper priest here …’

‘Whisht. We have, you and I, ignored that fine line up in the hills when poor souls came to us for absolution. Did it matter to them that they might as well have confessed their sins to a tree, or a stone? No, it did not. Neither does it matter to me. Listen, for my time is close. Will I go to God’s hall, or Hel’s hall, I wonder?’

His voice, no more than husk on the draught, stirred Drostan to life and he patted, soothingly.

‘Hell has no fires for you, brother,’ he declared firmly and the old monk laughed, brought on a fit of coughing and wheezed to the end of it.

‘No matter which gods take me,’ he said, ‘this is a straw death, all the same.’

Drostan blinked at that, as clear a declaration of pagan heathenism as he had heard. Sueno managed a weak flap of one hand.

‘My name, Sueno, is as close as these folk get to Svein,’ he said. ‘I am from Venheim in Eidfjord, though there are none left there alive enough to remember me. I came with Eirik to Jorvik. I carried Odin’s daughter for him.’

Sueno stopped and raised himself, his grip on Drostan’s arm fierce and hard.

‘Promise me this, Drostan, as a brother in Christ and in the name of God,’ he hissed. ‘Promise me you will seek out the Yngling heir and tell him what I tell you.’

He fell back and mumbled. Drostan wiped the spittle from his face with a shaking hand, unnerved by what he had heard. Odin’s daughter? There was rank heathenism, plain as sunlight on water.

‘Swear, in the name of Christ, brother. Swear, as you love me …’

‘I swear, I swear,’ Drostan yelped, as much to shut the old man up as anything. He felt a hot wash of shame at the thought and covered it by praying.

‘Enough of that,’ growled Sueno. ‘I have heard all the chrism-loosening cant I need in the thirty years since they dragged me off from Stainmore. Fucking treacherous bitch-fucks. Fucking gods of Asgard abandoned us then …’

He stopped. There was silence and wind hissed rain-scent through the wall cracks, making the woodsmoke and oil reek swirl chokingly. Sueno breathed like a broken forge bellows, gathered enough air and spoke.

‘Do not take this to the Mother of Kings. Not Gunnhild, his wife, Eirik’s witch-woman. Not her. She is not of the line and none of Eirik’s sons left to the bitch deserve to marry Odin’s daughter … Asgard showed that when the gods turned their faces from us at Stainmore.’

Drostan crossed himself. He had only the vaguest notions what Sueno was babbling, but he knew the pagan was thick in it.

‘Take what I tell you to the young boy, if he lives,’ Sueno husked out wearily. ‘Harald Fairhair’s kin and the true line of Norway’s kings. Tryggve’s son. I know he lives. I hear, even in this wild place. Take it to him. Swear to me …’

‘I swear,’ Drostan declared quietly, now worried about the blood seeping from between Sueno’s cracking lips.

‘Good,’ Sueno said. ‘Now listen. I know where Odin’s daughter lies …’

Forgotten in the dark, Martin from Hammaburg listened. Even the pain in his foot, that driving constant from toes that no longer existed – clearly part of the penance sent from God – was gone as he felt the power of the Lord whisper in the urgent, hissing, blood-rheumed voice of the old monk.

A sign, as sure as fire in the heavens. After all this time, in a crude stone hut daubed with poor clay and Christ hope, with a roof so low the rats were hunchbacked – a sign. Martin hugged himself with the ecstasy of it, felt the drool from his broken mouth spill and did not try to wipe it away. In a while, the pain of his foot came back, slowly, as it had when it thawed, gradually, after his rescue from the freeze of a steppe winter.

Agonising and eternal, that pain, and Martin embraced it, as he had for years, for every fiery shriek of it reminded him of his enemies, of Orm Bear-Slayer who led the Oathsworn, and Finn who feared nothing – and Crowbone, kin of Harold Fairhair of the Yngling line and true prince of Norway. Tryggve’s son.

There was a way, he thought, for God’s judgement to be delivered, for the return of what had been lost, for the punishment of all those who had thwarted His purpose. Now even the three gold coins, given to him by the lord of Kiev years since and never spent, revealed their purpose, and he glanced once towards the stone they were hidden beneath. A good hefty stone, that, and it fitted easily into the palm.

By the time the old monk coughed his blood-misted last at dawn, Martin had worked out the how of it.

Hammaburg, some months later …

Folk said it was a city to make you gasp, hazed with smoke and sprawling with hundreds of hovs lining the muddy banks and spilling backwards into the land. There were ships by the long hundred lying at wharfs, moored by pilings, or drawn up on the banks and crawling with men, like ants on dead fish.

There were warehouses, carts, packhorses and folk who all seemed to shout to be heard above the din of metalsmith hammers, shrieking axles and fishwives who sounded as like the quarrelling gulls as to be sisters.

Above all loomed the great timber bell tower of the Christ church, Hammaburg’s pride. In it sat a chief Christ priest called a bishop, who was almost as important as the Christ priest’s headman, the Pope, Crowbone had heard.

Cloaked in the arrogance of a far-traveller with barely seventeen summers on him, Crowbone was as indifferent to Hammaburg as the few men with him were impressed; he had seen the Great City called Constantinople, which the folk here named Miklagard and spoke of in the hushed way you did with places that were legend. But Crowbone had walked there, strolled the flower-decked terraces in the dreaming, windless heat of afternoon, where the cool of fountains was a gift from Aegir, lord of the deep waters.

He had swaggered in the surrounds of the Hagia Sophia, that great skald-verse of stone which made Hammaburg’s cathedral no more than a timber boathouse. There had been round, grey stones paving the streets all round the Hagia, Crowbone recalled, with coloured pebbles between them and doves who were too lazy to fly, waddling out from under your feet.

Here in Hammaburg were brown-robed priests banging bells and chanting, for they were hot for the cold White Christ here – so much so that the Danes had grown sick of Bishop Ansgar, Apostle of the North, burning the place out from underneath him before they sailed up the river. That was at least five score years ago, so that scarce a trace of the violence remained – and Crowbone had heard that Hammaburg priests still went out to folk in the north, relentless as downhill boulders.

Crowbone was unmoved by the fervour of these shaven monks for he knew that, if you wanted to feel the power of the White Christ, then Miklagard, the Navel of The World, was the place for it. The spade-bearded priests of the Great City perched on walls and corners, even on the tops of columns, shouting about faith and arguing with each other; everyone, it seemed to Crowbone, was a priest in Miklagard. There, temples could be domed with gold, yet were sometimes no more than white walls and a rough roof with a cross.

In Miklagard it was impossible to buy bread without getting a babble about the nature of their god from the baker. Even whores would discuss how many Christ-Valkeyrii might exist in the same space while pulling their shifts up. Crowbone had discovered whores in the Great City.

Hammaburg’s whores thought only of money. Here the air was thick with haar, like wet silk, and the Christ-followers sweated and knelt and groaned in fearful appeasement, for the earth had shifted and, according to some Engliscmonks, a fire-dragon had moved over their land, a sure sign that the world would end as some old seer had foretold, a thousand years after the birth of their Tortured God. Time, it seemed, was running out.

Crowbone’s men laughed at that, being good Slav Rus most of them and eaters of horse, which made them heathen in the eyes of Good Christ-followers. If it was Rokkr, the Twilight, they all knew none of the Christ bells and chants would make it stop, for gods had no control over the Doom of all Powers and were wyrded to die with everyone else.

Harek, who was by-named Gjallandi, added that no amount of begging words would stop Loki squirming the earth into folds and yelling for his wife to hurry up and bring back the basin that stopped the World Serpent venom dripping on his face. He said this loudly and often, as befits a skald by-named Boomer, so that folk sighed when he opened his mouth.

Even though the men from the north knew the true cause of events, such Loki earth-folding still raised the hairs on their arms. Perhaps the Doom of all Powers was falling on them all.

Crowbone, for his part, thought the arrogance of these Christ-followers was jaw-dropping. They actually believed that their god-son’s birth heralded the last thousand years of the world and that everyone’s time was almost up. Twenty years left, according to their tallying; good Christ children born now would be young men when their own parents rose out of their dead-mounds and everyone waited to be judged.

Crowbone was hunched moodily under such thoughts, for he knew the whims of gods only too well; his whole life was a knife-edge balance, where the stirred air from a whirring bird’s wing could topple him to doom or raise him to the throne he considered his right. Since Prince Vladimir of Kiev had turned his face from him, the prospect seemed more doom than throne.

‘You should not have axed his brother,’ Finn Horsehead growled when Crowbone spat out this gloomy observation shortly after Finn had shown up with Jarl Orm.

Crowbone looked at the man, all iron-grey and seamed like a bull walrus, and willed his scowl to sear a brand on Finn’s face. Instead, Finn looked back, eyes grey as a winter sea and slightly amused; Crowbone gave up, for this was Finn Horsehead, who feared nothing.

‘Yaropolk’s death was necessary,’ Crowbone muttered. ‘How can two princes rule one land? Odin’s bones – had we not just finished fighting the man to decide who ruled in Kiev and all the lands round it? Vladimir’s arse would never have stayed long on the throne if brother Yaropolk had remained alive.’

He knew, also, that Vladimir recognised the reality of it, too, for all his threats and haughtiness and posturing about the honour of princes and truces – Odin’s arse, this from a man who had just gained a wife by storming her father’s fortress and taking her by force. Yaropolk, the rival brother, had to die, otherwise he would always have been a threat, real or imagined and, one day, would have been tempted to try again.

None of which buttered up matters any with Vladmir, who had turned his back on his friend as a result.

‘There had been fighting, right enough,’ answered Orm quietly, moving from the shadows of the room. ‘But a truce and an agreement between brothers marked the end of it – at which point you axed Yaropolk between the eyes.’

But it was all posturing, Crowbone thought. Vladimir was pleased his brother was dead and would have contrived a way of doing it himself if Crowbone had not axed the problem away.

The real reason for the Prince of Kiev’s ire was that Crowbone’s name was hailed just as frequently as Vladimir’s now – and that equality could not be allowed to continue. It was just a move in the game of kings.

Crowbone fastened his scowl on the Bear-Slayer. A legend, this jarl of the Oathsworn – Crowbone was one of them and so Orm was his jarl, which fact he tried hard not to let scrape him. He owed Orm a great deal, not least his freedom from thralldom.

Eight years had passed since then. Now the boy Orm had rescued was a tall, lithe youth coming into the main of his years, with powerful shoulders, long tow-coloured braids heavy with silver rings and coins, and the beginning of a decent beard. Yet the odd eyes – one blue as old ice, the other nut-brown – were blazing and the lip still petulant as a bairn’s.

‘Vladimir could no more rule with his brother alive than I can fart silver,’ Crowbone answered, the pout vanishing as suddenly as it had appeared. ‘When he has had time to think of this, he will thank me.’

‘Oh, he thanks you, right enough,’ Finn offered, wincing as he planted one buttock on a bench. ‘It is forgiveness he finds hard.’

Crowbone ignored the cheerful Finn, who was clearly enjoying this quarrel among princes. Instead, he studied Orm, seeing the harsh lines at the mouth which the neat-trimmed beard did not hide, just as the brow-braids did not disguise the fret of lines at the corners of the eyes, nor the scar that ran straight across the forehead above the cool, sometimes green, sometimes blue eyes. The nose was skewed sideways, his cheeks were dappled with little poxmark holes, his left hand was short three fingers, and he limped a little more than he had the year before.

A hard life, Crowbone knew and, when you could read the rune-marks of those injuries, you knew the saga-tale of the man and the Oathsworn he led.

Unlike Finn there was no grey in Orm Bear-Slayer yet, but they were both already old, so that a trip from Kiev, sluiced by Baltic water that still wanted to be ice, was an ache for the pair of them. Worse still, they had snugged the ship up in Hedeby and ridden across the Danevirke to Hammaburg, which fact Finn mentioned at length every time he shifted his aching cheeks on a bench.

‘Did the new Prince of Kiev send you, then?’ Crowbone asked and looked at the casket on the table. Silver full it was, including some whole coins and full-weight minted ones at that. Brought with ceremony by Orm and placed pointedly in front of him.

‘Is this his way of saying how sorry he is for threatening to stake me? An offering of gratitude for fighting him on to the throne of Kiev and ridding him of his rival?’

‘Not likely,’ Orm declared simply, unmoved by Crowbone’s attempt at bluster.

‘You were ever over-handy with an axe and a forehead, boy,’ Finn added and there was no grin in his voice now. ‘I warned you it would get you into trouble one day – this is the second time you have annoyed young Vladimir with it.’

The first time, Crowbone had been nine and fresh-released from slavery; he had spotted his hated captor across the crowded market of Kiev and axed him in the forehead before anyone could blink. That had put everyone at risk and neither Orm nor Finn would ever forget or forgive him for it.

Crowbone knew it, for all his bluster.

‘So whose silver is this, then?’ Crowbone demanded, knowing the answer before he spoke.

Orm merely looked at him, then shrugged.

‘I have a few moonlit burials left,’ he declared lightly. ‘So I bring you this.’

Crowbone did not answer. Moonlit buried silver was a waste. Silver was for ships and men and there would never be enough of it in the whole world, Crowbone thought, to feed what he desired.

Yet he knew Orm Bear-Slayer did not think like this. Orm had gained Odin’s favour and the greatest hoard of silver ever seen, which was as twisted a joke as any the gods had dreamed up – for what had the Oathsworn done with it after dragging it from Atil’s howe back into the light of day? Buried it in the secret dark again and agonised over having it.

Because Crowbone owed the man his life, he did not ever say to Orm what was in his heart – that Orm was not of the line of Yngling kings and that he, Olaf, son of Tryggve, by-named Crowbone, had the blood in him. So they were different; Orm Bear-Slayer would always be a little jarl, while Olaf Tryggvasson would one day be king in Norway, perhaps even greater than that.

All the same, Crowbone thought moodily, Asgard is a little fretted and annoyed over the killing of Yaropolk, which, perhaps, had been badly timed. It came to him then that Orm was more than a little fretted and annoyed. He had travelled a long way and with few companions at some risk. Old Harald Bluetooth, lord of the Danes, had reasons to dislike the Oathsworn and Hammaburg was a city of Otto’s Saxlanders, who were no friends to Jarl Orm.

‘Not much danger,’ Orm answered with an easy smile when Crowbone voiced this. ‘Otto is off south to Langabardaland to quarrel with Pandulf Ironhead. Bluetooth is too busy building ring-forts at vast expense and with no clear reason I can see.’

To stamp his authority, Crowbone thought scathingly, as well as prepare for another war with Otto. A king knows this. A real jarl can understand this, as easy as knowing the ruffle on water is made by unseen wind – but he bit his lip on voicing that. Instead, he asked the obvious question.

‘Do you wish me to find someone to take my place?’

A little more harshly said than he had intended; Crowbone did not want Orm thinking he was afraid, for finding a replacement willing to take the Oath was the only way to safely leave the Oathsworn. There were two others – one was to die, the other to suffer the wrath of Odin, which was the same.

‘No,’ Orm declared and then smiled thinly. ‘Nor is this a gift. I am your jarl. I have decided a second longship is needed and that you will lead the crew of it. The silver is for finding a suitable ship. You have the men you brought with you from Novgorod, so that is a start on finding a crew.’

Crowbone said nothing, while the wind hissed wetly off the sea and rattled the loose shutters. Finn watched the pair of them – it was cunning, right enough; there was not room on one drakkar for the likes of Orm and a Crowbone growing into his power and wyrd, yet there were benefits still for the pair of them if Crowbone remained one of the Oathsworn. Perhaps the width of an ocean or two would be enough to keep them from each other’s throats.

Crowbone knew it and nodded, so that Finn saw the taut lines of the pair of them ease, the hackles drift downwards. He shifted, grinned and then grunted his pleasure like a scratching walrus.

‘Where are you bound from here?’ Crowbone asked.

‘Back to Kiev,’ Orm declared. ‘Then the Great City. I have matters there. You?’

Crowbone had not thought of it until now and it came to him that he had been so tied up with Vladimir and winning that prince his birthright that he had not considered anything else. Four years he had been with Vladimir, like a brother … he swallowed the flaring anger at the Prince of Kiev’s ingratitude, but the fire of it choked him.

‘Well,’ said Orm into the silence. ‘I have another gift, of sorts. A trader who knows me, called Hoskuld, came asking after you. Claims to have come from Mann with a message from a Christ monk there. Drostan.’

Crowbone cocked his head, interested. Orm shrugged.

‘I did not think you knew this monk. Hoskuld says he is one of those who lives on his own in the wilderness and has loose bits in the inside of his thought-cage. It means nothing to me, but Hoskuld says the priest’s message was a name – Svein Kolbeinsson – and a secret that would be of worth to Tryggve’s son, the kin of Harald Fairhair.’

Crowbone looked from Orm to Finn, who spread his hands and shrugged.

‘I am no wiser. Neither monk nor name means anything to me and I am a far-travelled man, as you know. Still – I am thinking it is curious, this message.’

Enough to go all the way to Mann, Crowbone wondered and had not realised he had voiced it aloud until Orm answered.

‘Hoskuld will take you, you do not need to wait until you have found a decent ship and crew,’ he said. ‘You have six men of your own and Hoskuld can take nine and still manage a little cargo – with what you pay him from that silver, it is a fine profit for him. Ask Murrough to go with you, since he is from that part of the world and will be of use. You can have Onund Hnufa, too, if you want, for you might need a shipwright of his skill.’

Crowbone blinked a little at that; these were the two companions who had come with Orm and Finn and both were prizes for any ship crew. Murrough macMael was a giant Irisher with an axe and always cheerful. Onund Hnufa, was the opposite, a morose oldster who could make a longship from two bent sticks, but he was an Icelander and none of them cared for princes, particularly if they came from Norway. Besides that, he had all the friendliness of a winter-woken bear.

‘One is your best axe man. The other is your shipwright,’ he pointed out and Orm nodded.

‘No matter who pays us, we are out on the Grass Sea,’ he answered, ‘fighting steppe horse-trolls, without sight of water or a ship. Murrough would like a sight of Ireland before he gets much older and you are headed that way. Onund does not like looking at a land-horizon that gets no closer, so he may leap at this chance to return to the sea.’

He stared at Crowbone, long and sharp as a spear.

‘He may not, all the same. He does not care for you much, Prince of Norway.’

Crowbone thought on it, then nodded. Wrists were clasped. There was an awkward silence, which went on until it started to shave the hairs of Crowbone’s neck. Then Orm cleared his throat a little.

‘Go and make yourself a king in Norway,’ he said lightly. ‘If you need the Oathsworn, send word.’

As he and Finn hunched out into the night and the squalling rain, he flung back over his shoulder, ‘Take care to keep the fame of Prince Olaf bright.’

Crowbone stared unseeing at the wind-rattling door long after they had gone, the words echoing in him. Keep the fame of Prince Olaf bright – and, with it, the fame of the Oathsworn, for one was the other.

For now, Crowbone added to himself.

He stirred the silver with a finger, studying the coins and the roughly-hacked bits and pieces of once-precious objects. Silver dirham from Serkland, some whole coins from the old Eternal City, oddly-chopped arcs of ring, sharp slivers of coin wedges, cut and chopped bar ingots. There was even a peculiarly shaped piece that could have been part of a cup.

Cursed silver, Crowbone thought with a shiver, if it came from Orm’s hoard, which came from Atil’s howe. Before that the Volsungs had it, brought to them by Sigurd, who killed the dragon Fafnir to possess it; the history of these riches was long and tainted.

It had done little good to Orm, Crowbone thought. He had been surprised when Orm had announced that he was returning to Kiev, for the jarl had been brooding and thrashing around the Baltic, looking for signs of his wife, Thorgunna, for some time.

She had, Crowbone had heard, turned her back on her man, her life, the gods of Asgard and her friends to follow a Christ priest and become one of their holy women, a nun.

That had been part of the curse of Atil’s silver on Orm. The rest was the loss of his bairn, born deformed and so exposed – the act which had so warped Thorgunna out of her old life – and the death of the foster-wean Orm had been entrusted with, who happened to be the son of Jarl Brand, who had gifted the steading at Hestreng to Orm.

In one year, the year after Orm had gained the riches of Atil’s tomb, the curse on that hoard had taken his wife, his newborn son, his foster-son, his steading, his friendship with the mighty and a good hack out of his fair fame.

Crowbone studied the dull, winking gleam of that pile and wondered how much of it had come from the Volsung hoard and how bad the curse was.

Sand Vik, Orkney, at the same time …

THE WITCH-QUEEN’S CREW

The wind blew from the north, hard and cold as a whore’s heart so that clouds fled like smoke before it and the sun died over the heights of Hoy. The sea ran grey-green and froth flew off the waves, rushing like mad horses to shatter and thunder on the headlands, the undertow smacking like savouring lips until the suck was crushed by another wild-horse rush.

The man shivered; even the thick walls of this steading did not seem solid enough and he felt the bones of the place shudder up through his feet. There was comfort here, all the same, he saw, but it was harsh and too northern, even for him – the room was murky with reek because the doors were shut against the weather and the wind swooped in through the hearthfire smokehole and simply danced it round the dim hall, flaring the coals and flattening flame. It made the eyes of the storm-fretted black cat glow like baleful marshlights.

A light appeared, seeming to float on its own and flickering in the wild air, so that the man shifted uneasily, for all he was a fighting man of some note, and hurriedly brought up a hand to cross himself.

There was a chuckle, a dry rustle of sound like a rat in old bracken and the night crawled back from the flame, revealing gnarled driftwood beams, a hand on the lamp ring, blackness beyond.

Closer still and he saw an arm but only knew it from the dark by the silver ring round it, for the cloth on it was midnight blue. Another step and there was a face, but the lamp blurred it; all the man could see clearly was the hand, the skin sere and brown-pocked, the fingers knobbed.

That and the eyes of her, which were bone needles threading the dark to pierce his own.

‘Erling Flatnef,’ said the dry-rustle voice, rheumed and thick so that the sound of his own name raised the hackles on his arm. ‘You are late.’

Erling’s cheeks felt stiff, as if he had been staring into a white blizzard, yet he summoned words from the depth of himself and managed to spit them out.

‘I waited to speak with my lord Arnfinn,’ he said and the sound of his voice seemed sucked away somehow.

‘Just so – and what did the son of Thorfinn Jarl have to say?’

The moth-wing hiss of her voice was slathered with sarcasm, for which Erling had no good reply. The truth was that the four sons of Thorfinn who now ruled Orkney were as much in thrall to this crumbling ruin, Gunnhild, Mother of Kings, as their father had been. Arnfinn, especially, was hag-cursed by it and had merely brooded his eyes into the pitfire and then waved Erling on his way without a word, trying not to look at his wife, Ragnhild, who was Gunnhild’s daughter.

Erling’s silence gave Gunnhild all the answer she needed. As her face loomed out from behind the blurring light of the lamp he was unable even to cross himself, was paralysed at the sight of it. Whatever The Lady wanted, she would get; not for the first time, Erling pitied the Jarls of Orkney and the mother-in-law they wore round their necks.

Not that it was an ugly face, aged and raddled. The opposite. It was a face with skin that seemed soft as fine leather with only a tracery of lines round the mouth, where the lips were a little withered. A harsh line or two here and there on it, which only accentuated the heart-leaping beauty that had been there in youth. Gunnhild wanted to smile at the sight of him, but knew that would crack the artifice like throwing a stone on thin ice. She used her face as a weapon and clubbed him with it.

‘I had a son called Erling,’ she said and Erling stiffened. He knew that – Haakon Jarl had killed him. For a wild moment of panic Erling wondered if she sought to raise the dead son and needed to steal the name …

‘I have a task for you, Flatnose,’ she said in her ruin of a voice. ‘You and my last, useless son Gudrod and that Tyr-worshipping boy of yours – what is his name?’

‘Od,’ Erling managed and mercifully Gunnhild slid away from him, back into the shadows.

‘Listen,’ she said and laid the meat of it out, a long rasp of wonder in that fetid dark. The revelations left him shaking, wondering how she had discovered all this, awed at the rich seidr magic she still commanded – the gods knew how old she was, yet still beautiful and still a power.

Later, as he stumbled from the hall, the rain and battering wind were as much of a relief as goose-grease on a burn.

TWO

The coast of Frisia, a week later …

CROWBONE’S CREW

IT was no properly straked, oak-keeled drakkar, but the Or-skreiðr was a good ship, a sturdy, fat-waisted knarr with scarred planks and the comfort of ship-luck. It had carried the trader safely from Dyfflin to Hammaburg and elsewhere – even back to the trader’s home in Iceland. Hoskuld boasted of its prowess as it hauled Crowbone and his Chosen Men out of Hammaburg to the sea, then west along the coast. The Or-skreiðr, Swift-Gliding, was Hoskuld’s pride.

‘Even when Aegir of the waters is splashing about in the worst way,’ he declared, ‘I have never had a moment’s unease.’

Crowbone’s eight Oathsworn, jostling for sea-chest space with the crew and the cargo of hoes and mattocks and kegged fish, found little humour in this, though some gave dutiful laughs. But not Onund.

‘You should not dangle this stout ship in front of the Norns, like a worm on a hook,’ Onund growled morosely to Hoskuld. ‘Those Sisters love to hear the boasts of men – it makes them laugh.’

Crowbone said nothing, for he knew Onund had sourness seeped into him, for all he had agreed to this voyage. The other men were less frowning about matters. Murrough macMael was going back to Mann and possibly Ireland and that pleased him; the others – Gjallandi the skald, Rovald Hrafnbruder, Vigfuss Drosbo, Kaetilmund, Vandrad Sygni and Halfdan Knutsson – were happy to be going anywhere with the Prince Who Would Be King. They were all seasoned Swedes and half-Slavs who had been down the cataracts from Kiev with the silk traders at least once and had sailed up and down the Baltic with Crowbone, raiding in the name of Vladimir, Prince of Novgorod and now Kiev.

Ring-coated most of them, exotic in fat breeks and big boots and fur-trimmed hats with silver wire designs, they swaggered and bantered idly in the fat-waisted little knarr and made Hoskuld and his working men scowl.

‘How do we know their worth?’ one seaman grumbled in Crowbone’s hearing. ‘Who decided on these instead of a decent cargo?’

‘They think we are just barrels of salt cod,’ Gjallandi announced, appearing suddenly at Crowbone’s ear, ‘while your new Chosen Men believe it is a day’s sail, with a bit of sword-waving at the end of it and yourself crowned king of Norway, no doubt. All will find the truth of matters, soon enough.’

He was shaking his head, which made all those who did not know him laugh, for he was not the figure of a raiding man. He was a middling man in most respects save two – his head and his voice.

His head was large, with a chin like a ship’s prow and two full, beautiful lips in the centre of it, surrounded by a neat-trimmed fringe of moustache and beard. The hair on his head was marvellously copper-coloured, but galloping back over his forehead on either side of his ears; when the wind blew it stuck straight out behind him like spines. Murrough said it was not his hair that was receding but his head growing from all the lore he stuffed in it.

That lore and his voice had made his fortune, all the same, first as skald to a jarl called Skarpheddin and then to Jarl Brand. He had left Brand after arguing that it was not right to come down so hard on Jarl Orm for the loss of Jarl Brand’s son – which, according to Murrough and others, showed how Gjallandi’s voice sometimes worked before his thought-cage did.

Now he had come with Crowbone because, he said, Crowbone had more saga in him and the tale of the exiled Prince of Norway reclaiming his birthright was too good to miss. Crowbone had joined in the good-natured laughter, but secretly liked the idea of having someone spread his fame; the thought was as warming a comfort as a hearthfire and a horn of ale.

‘The crowning will come in time,’ Crowbone answered, loud enough for everyone to hear. ‘Until then, there are ships and men waiting to join us.’

‘No doubt,’ said the steersman whose name was Halk and his Norse was strange and lilting. ‘Do they know you are coming?’

His voice had a laugh in it which removed any sting and Crowbone smiled back at him.

‘If you know where you are going,’ he replied, ‘then – there they will all be.’

It was clear that Hoskuld had told his men nothing much, which was not sensible in a tight crew of six who depended on each other and the trade they made. Crowbone did not much trust Hoskuld, for all he had come from Mann to deliver his mysterious message – without pay, no doubt, for Christ monks were notoriously empty-pursed.

‘For the love of God,’ Hoskuld had replied when Crowbone had asked the why of this and his face, battered by wind and wave into something like a headland with eyes, gave away nothing. His men said even less, keeping their eyes and hands on work, but Crowbone felt Hoskuld’s lie like a chill haar on his skin. Yet Hoskuld was a friend of Orm and that counted for much.

Crowbone sat and watched the land slip sideways past him while the sea rose and fell, dark, glassy planes heaving in a slow, breathing rhythm.

He watched the gulls. Hoskuld never got far enough from the land to lose them and Crowbone listened to them scream to each other of finding something that moved and promised fish. One perched on the mast spar, heedless of the sail’s great belly and Crowbone watched this one more carefully than the others. He felt the familiar tightening of the skin on his arms and neck; something was happening.

The crew of the Or-skreiðr coiled lines, bailed, reefed sail, took the steering oar and stared at Crowbone and his eight men. He could almost feel their dislike and their distrust and, above all, their fear. Here were the plunderers, pillagers and pagans that peaceful Christ-anointed traders, farmers of the sea-lanes, could do without as they ploughed up and down from port to port.

Here were red murderers, sitting on their sea-chests, talking in their mush-mouthed East Norse way – made worse by all the time spent with Slavs – and eyeing up the crew with almost complete indifference when not with sardonic smiles at watching men work while they stayed idle.

Crowbone knew his eight Chosen well, knew who was more Svear than Slav, who had washed that weekday, who doubted their own prowess.

Young men – well, all but Onund – hard men, who had all, without showing fear, taken that hard oath of the Oathsworn: we swear to be brothers to each other, bone, blood and steel, on Gungnir, Odin’s spear we swear, may he curse us to the Nine Realms and beyond if we break this faith, one to another.

Crowbone had taken it when he was too young for chin hair, driven to it as those desperate and lost in the dark will run to a fire, even if it risks a scorching. He had kin somewhere, sisters he had never seen – but mother, father, guardian uncle were all dead and Orm Bear-Slayer of the Oathsworn was the nearest thing he had to any of the three.

He watched his Chosen Men. Only Onund knew what the Oath meant, for he had taken it long enough ago to have marked the warp of it on his life. Most of the others would come to know just what they had sworn, but for now they were all grins and wild beards in every colour save grey, laughing and boasting easily, one to the other.

Hoskuld, beaming at the way they were skipping along, announced that he had many skills, one of them navigation.

‘We go out on to a big expanse of water dead ahead,’ he added. ‘Land on the berthing side, so you cannot really miss it. After a bit, we turn north. That is to the right. The steerboard side. The hand you use to pull yourself off.’

Crowbone forced a smile as Hoskuld moved off into the grins of his crew, while Murrough turned and looked at his fellow Oathsworn lazing there.

‘Never be minding, lads,’ he bellowed. ‘We have bread and fish and water if this short-arsed little trading man loses us. Also, there are Crowbone’s birds to steer by, when all else fails.’

Crowbone raised one hand in acknowledgement, while Hoskuld and his crew stared for a moment, stilled. Then they busied themselves and Crowbone smiled, for he knew no Norseman, especially Christ-sworn, liked the idea of a seidr-man and none of these liked to be reminded of the strange tales that surrounded Crowbone.

‘We will need no magic birds to get us where we are going,’ Hoskuld said eventually, with the scowl of an outraged Christmann. ‘Nor will I lose my way, Irisher. This is a ship blessed with God-luck.’

Right there, the lone gull on the mast spar took off from its perch and screamed, a mad laughing as it turned and wheeled away back towards the grey-blue line that was land. Crowbone watched it go, the hairs stiff on him; it does no good to tempt the Norns, he was thinking.

‘There was once a Chosen Man in the service of a jarl, don’t ask me where, don’t ask me when,’ he said and the heads came up. Crowbone had not meant to speak; he never did when the tales came on him, but those who had heard him before leaned forward a little. The steersman laughed but Murrough wheeshed him and the silence allowed the wind to thrum the rigging lines.

‘As part of his due he used to get bread and a bowl of honey each day,’ Crowbone went on, soft and gentle as the breathing sea. ‘The warrior ate the bread and put the honey into a stoppered jug, which he took to carrying around with him, lest it be stolen. He wanted to keep the jug until it was full, for he knew the high price his honey would fetch in the market.’

‘A sensible trading man, then, this warrior,’ Hoskuld offered sarcastically, but glares silenced him.

‘I will sell my honey for a piece of gold and buy ten sheep, all of which will bring forth young, so that in the course of one year I shall have twenty sheep,’ Crowbone said, the words tumbled from him, like slow, sticky sweetness from the tale’s jug.

‘Their number will steadily increase, and in four years I shall be the owner of four hundred sheep. I shall then buy a cow and an ox and acquire a piece of land. My cow will bring forth calves, the ox will be useful to me in ploughing my land, while the cows will provide me with milk. In five years’ time the number of my cattle will have increased considerably and I shall be wealthy. I shall then build a magnificent steading, acquire thralls and marry a beautiful woman of noble descent. She will become pregnant and bear me a son, a strong boy fit to carry my name. A lucky star will shine at the moment of his birth and he will be happy and blessed, and bring honour to my name after my death. Should he, however, refuse to obey me, I will whack him round the ear, thus—’

Crowbone smacked one fist into his palm, so that the listeners started a little.

‘So saying,’ Crowbone added softly, ‘he lashed out at the imaginary child. The jug flew from under his arm and smashed. The honey ran into the mud and was lost.’

‘Heya,’ sighed Murrough and stared pointedly at Hoskuld, who laughed nervously. The steersman crossed himself; no-one had missed the point of the tale.

The gull – the same one, Crowbone was sure – screamed with faint laughter in the distance.

Not long after, the steering oar broke.

One blink they were sailing along, scudding under a sail bagged full of wind, with the blue-grey slide of the land distant on one side. The next, Halk was yelling and hanging grimly on to the whole weight of the steering oar, which had parted company from the ship entire and looked set to go over the side. The Swift-Gliding leaped like a joyous stallion spitting out the bit, then yawed off in a direction all its own.

Men sprang to help Halk, wrestling the steering board safely on to the ship. Hoskuld, bawling orders, found the Oathsworn suddenly alive, moving with practised ease to flake the sail down on to the yard and bring the free-running knarr to a sulky halt, where it rocked and pitched, the slow-heaving waves slapping the hull.

‘Leather collar has snapped,’ Onund declared after a brief look. ‘Fetch out some more and we will fix it.’

Hoskuld glared at Halk, whose eyes were wide with innocent protesting, but then Gorm stepped into Hoskuld’s scowl and matched it with one of his own. He had been with Hoskuld ever since they had first set keel on water, so he had leeway. He had hands and face beaten by weather, but his eyes were clear and there was at least a horn-spoon of intellect behind them, even if his nose was crooked from fights and his body a barrel which had been scoured by wind and wave.

‘Not Halk’s fault,’ he growled at Hoskuld. ‘Should have stayed in Dyfflin for long enough to fetch such supplies as spare leather, but you would sail. Should have stayed in Sand Vik longer than to pick up this poor dog of a steersman, but you sailed even faster from there.’

‘Enough!’ roared Hoskuld, his face turning white, then red. ‘This is not fixing matters.’

He broke off, glanced at the thin line of land and wiped his mouth with the back of one hand.

‘This is the Frisian coast,’ he muttered darkly. ‘No place to be wallowing, dangled like a fat cod for sharks.’

‘Leather,’ Onund grunted.

‘None,’ Gorm replied, almost triumphant. ‘Some bast line, which will have to do.’

‘Aye, for you never stayed long enough in Dyfflin or Sand Vik,’ Crowbone noted and everyone heard how his voice had become steeled.

‘Save for picking up a steersman,’ he added, nodding towards Halk, who stared from Hoskuld to Crowbone and back, his mouth gawped like a coal-eater.

Folk left off what they were doing then, for a chill had sluiced in like mist, centred on Crowbone and the lip-licking Hoskuld.

Crowbone knew now where the steersman had his lilting Norse from. From Orkney, where Hoskuld had gone from Dyfflin and before that from Mann. Mann to Dyfflin to Orkney.

‘You know who this Svein Kolbeinsson is,’ Crowbone said, weaving the tale as he spoke and knowing the warp and weft were true by the look in Hoskuld’s eyes.

‘How many others have you told?’ Crowbone went on. Hoskuld spread his arms and tried to speak.

‘I …’ began Hoskuld.

Crowbone drew the short-handled axe out of the belt-ring at his waist and Hoskuld’s crew shifted uneasily; one made a whimpering sound. Hoskuld seemed to tip sideways and sag a little, like an emptying waterskin. The crew and the Oathsworn watched, slipping subtly apart.

‘You know from Orm what I can do with this,’ Crowbone said, raising the axe, and Hoskuld blinked and nodded and then rubbed the middle of his forehead, as if it itched.

‘Only because you have friendship with Jarl Orm is it still on the outside of your skull,’ Crowbone went on, in a quiet and reasonable voice, so that those who heard it shivered.

‘Svein Kolbeinsson,’ Hoskuld gasped. ‘Konungslykill, they called him. I was younger than yourself by a few years when I met him, on my first trip to Jorvik with my father.’

Crowbone stopped and frowned. Konungslykill – The King’s Key – was the name given to only one man, the one who carried King Eirik’s blot axe. Such sacrifice axes were all called Odin’s Daughter, but only one truly merited the name – Eirik’s axe, the black-shafted mark of the Yngling right to rule.

Carried by a Chosen Man called the King’s Key, the pair of them represented Eirik’s power to open all chests and doors in his realm, by force if necessary. It gave Eirik his feared name, too – Bloodaxe. Crowbone blinked, the thoughts racing in him like waves breaking on rocks.

‘This ship it was,’ Hoskuld said wistfully. ‘The year before Eirik was thrown out of Jorvik and died in an ambush set by Osulf, who went on to rule all Northumbria.’

What was that – twenty-five years ago and more? Crowbone looked at Hoskuld and while the gulls in his head screeched and whirled their messages and ideas, his face stayed grim and secret as a hidden skerry.

‘Svein Kolbeinsson was taken at the place where Eirik of Jorvik died, but after some time he escaped thralldom and fled to Mann. It seems he turned his back on Asgard since the gods turned their backs on him, so he became a monk of the Christ in the hills of Mann around Holmtun, in the north of the island. He died recently, but before he did, he told this monk Drostan a secret, to be shared only with the kin of the Yngling line.’

The words spilled from Hoskuld like a stream over rocks, yet the last of it clamped his lips shut as he realised what he had said. Crowbone nodded slowly as the sense of it crept like honey into his head.

‘Instead, you went to Dyfflin,’ Crowbone said softly.

Hoskuld licked his cracking lips and nodded.

‘At Drostan’s request,’ he murmured hesitantly.

‘You are no fool, Hoskuld Trader, you got the secret from this monk Drostan, you know what he has to tell me.’

‘Only what it is,’ he managed, in a husked whisper. ‘Odin’s Daughter. Not where it lies, though.’

‘Eirik’s axe, Odin’s Daughter itself, still in the world and a monk has the where of it in his head,’ Crowbone said.

Now it was the turn of the Oathsworn to shift, seeing the bright prize of Eirik’s Bloodaxe, the mark of a true scion of the Yngling line – a banner to gather men under. That and the magic in it made it worth more than if it were made of gold.

‘Olaf Irish-Shoes, Jarl-King in Dyfflin?’ Crowbone mused, bouncing the axe in his fingers. ‘Well, he is old, but he is still a northman and no man hated Eirik Bloodaxe more than he – did they not chase each other off the Jorvik High Seat?’

Hoskuld bobbed his head briefly in agreement and those who knew the tale nodded confirmation at each other; Eirik had been ousted from Jorvik once and Olaf Irish-Shoes at least twice. Gorm muttered and shot arrowed scowls at his captain.

‘Well,’ said Crowbone. ‘You took the news to Irish-Shoes, then Orkney.’ Crowbone’s voice was all dark and murder now. ‘Not to Thorfinn, I am thinking.’

‘Thorfinn died,’ Gorm blurted. ‘His sons rule together there now – Arnfinn, Havard, Ljot and Hlodir.’

‘There is only one ruler on Orkney,’ Crowbone spat. ‘Still alive is she, the Witch?’

Hoskuld answered only with a choking sound in his throat; Gunnhild, Eirik’s queen, the Witch Mother of Kings. The tales of her were suddenly fresh as new blood in Hoskuld’s head: she it was who had sent her sons to kill Crowbone’s father then scour the world for the son and his mother. Now the hunted son stood in front of him with an axe in his hand and a single brow fretted above his cold, odd eyes. Hoskuld cursed himself for having forgotten that.

‘Arnfinn is married to her daughter,’ he muttered.

Crowbone hefted the little axe, as if balancing it for a blow.

‘So,’ he said. ‘You took the news to Olaf Irish-Shoes, who was always Eirik’s rival – did you get paid before you fled? Then you took it to Gunnhild, the Witch, who was Eirik’s wife. You had to flee from there, too – and for the same reason. Did you ken it out at that point, Hoskuld Trader? That what you knew was more deadly than valuable?’

He stared at Hoskuld and the axe twitched slightly.

‘You are doomed,’ Crowbone declared, grim as lichened rock. ‘You are as doomed as this Drostan, whom you doubtless betrayed for profit. Olaf will want your mouth sealed and so will the Orkney Witch. Where is Drostan? Have you killed him?’

Hoskuld’s brows clapped together like double gates.

‘Indeed no, I did not. Him it was who asked to go to all these places, then finally to Borg in the Alban north, where we left him to come to find Jarl Orm, as he asked.’

He tried to keep the glare but the strange, odd-eyed stare of the youth made him blink. He waved his hands, as if trying to swat the feel of those eyes off his face.

‘The monk lives – why would I kill him, then bother to come and find Orm – and you?’

‘Betrayal,’ Crowbone muttered. He leaned a little towards Hoskuld’s pale face. ‘Is that what this is? An enemy who wants me dead, or worse? Why sail to Mann if the monk is at Borg?’

‘He left something with the monks on Mann,’ Hoskuld admitted. ‘A writing.’

Crowbone asked and Hoskuld told him.

‘A message. I was to pick it up on the return and take it to Orm.’

To Orm? Crowbone closed one thoughtful eye. ‘And you delivered it?’

Hoskuld nodded.

‘You know what this message spoke?’ he asked and watched Hoskuld closely.

The trader shook his head, more sullen than afraid now.

‘I was to tell you of it,’ he replied bitterly, ‘when you asked why we were headed for Mann at all.’

Crowbone did not show his annoyance in his face. It was a hard truth he did not care to dwell on, that he had simply thought Mann was where Hoskuld wanted to go with his strange cargo. Either he was paid more after that, or Crowbone found a ship of his own was what the young Prince of Norway had assumed.

Now he knew – a message had been left by this Drostan, in Latin which Hoskuld did not read – he knew runes and tallied on a notched stick well enough, so he could carry it to Orm and not know the content.

And the thought slid into him like a grue of ice – there was a trap to lure him to Mann.

He said so and saw Hoskuld’s scorn.

‘Why would Orm set you at a trap?’ he scathed. ‘He knows the way of monks. They would not have written this message to Orm only once.’

That was a truth Crowbone had to admit – monks, he knew, would copy it into their own annals and if he went to Mann he would find it simply by saying Orm’s name and asking with a silver offering attached. For all that, he wanted to bury the blade in the gape-mouthed face of the trader, but the surge of it, which raised his arm, was damped by a thought of what Orm might have to say. He had fretted Orm enough this year, he decided – yet the effort not to strike burst sweat on him. In the end, the lowering of his arm came more from the nagging to know what this writing held than any desire to appease Orm.

‘Get me to Mann, trader,’ he managed to harsh out. ‘I may yet feed you to the fish if it takes too long a sailing – or if I find this message or you plays me false.’

‘We are sailing nowhere,’ Onund interrupted with an annoyed grunt, bent over the steering oar so that his hunched shoulder reared up like an island. ‘We are drifting until this is lashed. Fetch what line you have – I can get us to land safely and then we will need to find decent leather.’

‘I would hurry, hunchback,’ said Halk the Orkneyman, staring out towards the distant land. ‘It would seem the sharks have found their cod.’

He pointed, leading everyone’s eyes to the faint line, marked with little white splashes where oars dug, which grew steadily larger.

‘It is all of us who are doomed,’ Gorm hissed, his eyes wide, then jumped as Kaetilmund clapped him on the back.

‘Ach, you fret too much,’ he said.

Gorm saw the Oathsworn moving more swiftly than he had seen them shift since they had come aboard. Sea-chests were opened, ringmail unrolled from sheepskins, domed helmets brought out, oiled against the sea-rot and plumed with splendid horsehair.

‘Our turn to do the work,’ Murrough macMael grunted and hefted his long axe, grinning. ‘You can join in if you like, or just watch.’

Gorm licked his lips and looked at the rest of the Swift-Gliding crew, who all had the same stare on them.

Not fear. Relief, that they were not Frisians.

Hrodfolc was smiling, though his teeth hurt. He did not have many left, yet the few he had hurt all the time these days – but even the nagging pain of them could not keep the smile from his face, laid there when the watchers brought word to the terp that a fat cargo ship was wallowing like a sick cow just off the coast.

It had been a time since such a prize had come their way. Ships sped past this stretch of coast like arrows, Hrodfolc thought, half-muttering to himself, for they know the red-murder fame of the folk living along it.

He turned to where his twenty men pulled and sweated, grunting with the effort, slicing the long snake-boat through the slow, rolling black swell. No mast and no sail on his boat, which is how cargo ships with a good wind at their back could always outrun us, Hrodfolc thought, leaving us rowing in their wake.

Not this time. This time, there would be blood and booty.

‘Fast, fast,’ he bellowed, the boom of his voice in his head bursting tooth-pain in him. The riches called to him and he could see them, taste them – wool and grain and skins. Casks filled with salt fish, or beer, or cheeses; boxes stuffed with bone, buckles, boots, pepper. Perhaps even gold and silver. Honey, or some other lick of sweetness after a long winter. His mouth watered.

‘Fast,’ he called and his men grunted and pulled, wild-haired, mad-bearded, their weapons handy to grab up when they left off the oars and flung them inboard.

Hrodfolc eyed the fat ship, focusing the pain on them, the ones on the ship. He would rend them. He would tear them …

They streaked up to the side of the slow-rocking cargo ship and saw pale faces, four, maybe six and that widened Hrodfolc’s brown smile. The oars backed water furiously, then clattered inboard a breath or two before the long, sleek boat kissed the side of the knarr, a gentle dunt. Men hurled up lines to lash themselves to the side; others grabbed up weapons and scrambled to climb up the thwarts of their higher-sided victim, Hrodfolc snarling ahead of the pack with an axe in either fist.

It was a surprise to them all, then, when a line of shields suddenly rose up and slapped together like a closing door. It was shock when a great, bearded axe on a long shaft arced out from under them, making Hrodfolc shy away sideways, though he was not the target of it. The axe chunked over the thwarts, the powerful arms wielding it snugging the snake-boat to the knarr like a lover cinching the willing waist of his girl into an embrace.

Crowbone saw the gaping, snaggle-toothed mouth of the man who led these Frisian raiders, his face a great rune of terror at the sight of the shields and ring-mailed, spear-armed men who stood behind them, scowling from under the rims of horse-plumed helmets.

Crowbone hurled his own spear and it took the man in the middle of his twisted tooth, which flew out of his mouth as he fell backwards, spraying blood and head-gleet all over his own men. He hurled his second spear with his left hand and it went through the thigh of another Frisian, pinning the man to the deck of the snake-boat – his screeches were as high as a gull’s.

Yet more spears flicked and the men on the snake-boat screamed and flapped like fox-stalked chickens. A few grabbed up oars and tried to push their boat away, but Murrough’s long axe and a grip like a steel band held them. There were splashes as men hurled themselves into the sea rather than wait to die, for the Oathsworn were pillars of iron with big round shields, spears which they hurled and blades which they followed up with, crashing to the rocking deck of the snake-boat. The Frisian raiders had cheap wool the colour of mud and charcoal, spears with rusted heads and little wood axes.

Some did not even have that and Drosbo took a half-pace backwards as a raider with a knife, fear-maddened to fighting like a desperate rat in a barrel, hurled himself forward, screaming, slashing. The knife scored down the ringmail with little hisses of sound and Drosbo let him do it for the time it took him to grin and the Frisian to realise it was doing no good.

Just at the point the Frisian thought of aiming for the face, Drosbo brought his sword down in a cutting stroke that took the man in the join between neck and shoulder, a great, wet-sounding chop that popped the blade out of the man’s armpit and the whole arm, knife and all, into the sea.

Then Drosbo booted him in the chest, hard enough to pitch the shrieking raider into the slow-shifting, crow-black water in a whirl of blood.

There was a moment of crouching caution, then Murrough gave a coughing grunt, like a new-woken bear, and offered a final spit on the whole affair as he worked his bearded axe loose from the snake-ship’s planks and straightened, rolling the overworked muscles of neck and shoulder. Hoskuld’s crew stared at the astounded, gape-mouthed dead, at the blood washing greasily in the bowels of the snake-boat, at those still alive and swimming hopelessly for the far-away shore, black, gasping heads rising and sinking on the glass swell.

‘That is that, then,’ Onund growled out and clapped the stunned Orkneyman on the shoulder. ‘See if you can find some decent rope.’

Holmtun, Isle of Mann, at the same time

THE WITCH-QUEEN’S CREW

The wind rushed the trees and then bowled on over the scrub and broom, ruffling it like a mother does a son’s hair. Birds hunched in shelter, or were ragged away from where they wanted to go, steepling sideways and too busy even to make a voice of protest.

The sun was there, all the same, for the heat of it made riding in ringmail and wool a weary matter and the glare of sky, white as a dead eye, made Ogmund squint.

He was tired. They were all tired from plootering over hill and heather, a trail of curse and spit, the hooves of weary horses clacking on loose stones.

Somewhere ahead, Ogmund thought, scanning the distance and squinting until his forehead ached, were the raiders. On foot. How could folk on foot have kept ahead so well? And who were they, who dared to raid this corner of Mann, which had not been raided in years?

‘A warrior,’ said a voice as if in answer and Ogmund turned to where Ulf, forcing himself taller in his saddle to see better, was pointing ahead to the wooded hill. He had good eyes did Ulf and Ogmund saw the figure, dark against the glare.

‘So, we have caught them, then,’ he said and felt the relief of the men behind him, for it meant they could get off the horses and ease their arses. Even as he swung a leg over and slid to the ground, feeling his legs buckle a little, Ogmund kept staring at the figure on the hill. Unconcerned, was the word that sprang to his mind, as if the man was picking his teeth after a meal of bread and cheese. Ogmund felt a stir of unease and looked round at his own men for the comfort of seeing them sorting out weapons and tying chinstraps.

‘What are you thinking on this, Ogmund?’ asked Ulf.

That it smells, Ogmund wanted to say. That the monks whose mean little church was raided spoke of three men only and I have twenty, so should be feeling less like a maiden with a knowing hand on her knee.

Ogmund spread his hands and summed up the situation for his own benefit.

‘A monk had his face stirred up a little,’ Ogmund said, aware even as he spoke that it sounded like a whine. ‘Nothing of value was taken and some of their precious vellum was creased. Seems a strange crime to me, three raiders in ringmail and with good weapons and nothing of value stolen at all. Vellum and parchment taken and read and returned. When did you know ragged-arsed bandits who could read monk scratchings?’

‘Try telling that to Jarl Godred,’ Ulf replied shortly. It was clear he thought they should all be moving up the slope with shields set and weapons out; Ogmund had no doubt he would say as much to Godred as soon as he could flap his mouth close to the jarl’s ear and the jarl would have much to say to Ogmund as a result, none of it pleasant. Not for nothing was the ruler of this little part of Mann called Hardmouth – though never to his face.

For this reason, and because the weather was foul, Ogmund had not complained when not long since Godred chose Ulf to go and ferret out the truth of a report that two dead monks were to be found in a remote hut in the hills. Ulf had found them, two rat-eaten bodies. He was still bragging about it, though he had faced no threat, as Ogmund pointed out. Here was the opposite case, no serious crime had occurred yet the danger was very real. Ulf clearly wanted to show Ogmund, not to mention Jarl Godred, how ready he was to face any threat.

Ogmund sighed and waved the men forward, signalling for three to act as horse-holders. Ulf stayed mounted, which annoyed Ogmund since it made Ulf look like the leader. Ogmund would have liked to command him to get off, but knew that would look petty. He wanted to get back on his own mount but was not sure he had the strength of leg to spring up on it in his ringmail and felt the crushing despair of knowing there had been a time when he would have done it without thinking.

Too old, he thought grimly. Everyone knows it and Ulf grows impatient to be in my place.

The figure on the hill was suddenly close, so that Ogmund was startled at how he had daydreamed a mournful way to this point without realising it. He shook himself like a dog to sharpen his wits and stared at the man on the hill.

He was big and wore a helmet with ringmail covering the front of it so that none of his face could be seen at all; the eyes were no more than points of light in the cave of his shadowed face. It had gilded eyebrows and a raised crest and was altogether a fine helm, which had been greased and oiled carefully. The wearer had a long coat of ringmail, too, was thick-waisted, but not fat, had a shield slung on his back and one hand resting lightly on the hilt of a sword in a tooled leather sheath – though the hilt of the weapon was plain iron and sharkskin grip, without decoration.

All of it only increased the rise of Ogmund’s hackles. A little raiding man might well have a fine helmet, but he would not have bothered so much in the care of it, having almost certainly stolen it in the first place. Nor did this one stand like a little raiding man. He stood as if he owned the ground his feet were on.

‘Who are you?’ Ogmund demanded.

‘Gudrod Eiriksson from Orkney.’ The voice was metal-muffled, inhuman and that rocked a few back on their heels as much as the name. Bloodaxe’s son? Here in Mann?

‘Orkney does not rule here now,’ Ulf sneered.

‘Not now,’ replied Gudrod easily, ‘but soon enough again, maybe.’

Another man appeared from the trees, ring-mailed and armed, moving quietly to the left and slightly behind Gudrod. He had a sharp face and a weasel smile, hardly softened at all by the trim line of his beard. His nose was broad and spread out, as if he had been hit with a shovel and it fascinated Ogmund.

A third slid out, wearing a red tunic and green breeks, both so faded they held only a distant laugh of colour. He had a sword thrust through a ring in his belt but wore no armour at all, not even a helmet, and his face was round and boy-smooth, unmarked by war or weather so that the black hair which framed it made the youth look like an angel Ogmund had seen painted on the rough wall of the big church in Holmtun. Yet this angel moved strangely; like a padding wolf.

‘You robbed a church,’ Ulf went on and Ogmund finally had had enough. The casual trio, the whole raid, had him ruffled as a wet cat and Ulf taking on the mantle of leader here was more than enough.

‘When I need you to speak, Ulf Bjornsson,’ he said, low and harsh as grinding quernstones, ‘I will find a dog and have it bark.’

Someone snickered at the back and Ulf jerked his reins so hard the horse threw up its head in protest and scattered bit-foam.

‘You lead here?’ demanded Gudrod and Ogmund nodded. The man with the squashed nose laughed, a high, thin sound. Ogmund saw his top lip stick to his teeth; that sign of nerves gave him a little comfort. He realised, suddenly, that the man had no bone in his nose, which gave it the look.

‘There was no harm done in the church,’ Gudrod went on easily in that hollow-helmet voice. ‘It was a misunderstanding. We sought enlightenment only, not riches. A priest decided that we were not Christian enough for him. And here is me, baptised and everything, as fine a Christian as yourself, whoever you are.’

‘Ogmund Liefsson, of Jarl Godred’s Chosen,’ Ogmund replied automatically, cursing himself for his lack of manners.

‘Godred? Is that Godred, son of Harald? The one who is called Hardmouth much of the time?’ demanded Gudrod, his light, amused tone still apparent even filtered through the ringmail over his mouth. ‘Does he still bellow like a bull with a wasp up its arse?’

A few men chuckled and Ogmund turned a little to silence them.

‘What enlightenment?’ demanded Ogmund, deciding to ignore Gudrod’s question. ‘What brings the last of Eirik Bloodaxe’s sons all the way to a wee chapel in the wilds of Mann? Is your mam looking for a priest to confess her sins to?’

The implication that there was no-one closer who would absolve Gunnhild did not wing its way past those behind Ogmund and there were more chuckles, which Ogmund was pleased to hear.

Gudrod may have scowled under his helmet, but only he knew. The hands shifted, spreading wide in a graceful gesture, like a smile.

‘We sought a priest, certainly,’ Gudrod replied. ‘Though it appears he is not to hand. So we will leave as peacefully as we came.’

‘Ha!’ roared Ulf. ‘You and your handful will get what you deserve – the end of a rope.’

The head turned to him and even Ogmund felt the wither of those unseen eyes.

‘Whisht, boy,’ said the metal voice. ‘Men are speaking here.’

Ulf howled then and Ogmund heard the snake-hiss rasp as he dragged his blade out.

‘Stay!’ he roared out, but Ulf had blood in his eye and was kicking the horse, which had started to doze and was now sprung awake. Shocked, it leaped forward and, without stirrups, Ulf swayed off-balance, so that his sword waved wildly.

‘Od,’ said the flat-nosed man. ‘Kill him.’