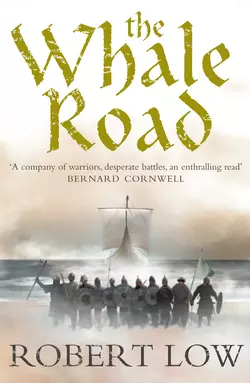

The Whale Road

Robert Low

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 577.47 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 18.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: DISCOVER SOMETHING NEW WITH THIS LIMITED-TIME DISCOUNT ON BOOK ONE OF THE SERIES.The first in the Oathsworn series, charting the adventures of a band of Vikings on the chase for the secret hoard of Attila the Hun.In time with the magnificent British Museum Viking exhibition, comes the Oathsworn series, called ‘enthralling’ by fiction legend Bernard Cornwell, and known for its blockbuster battles and powerful suspense.Life is savage aboard a Viking raider. Young Orm Rurikson is plucked from the snows of Norway to join his estranged father on the Fjord Elk, and becomes a member of the notorious crew – the Oathsworn. Hired as relic-hunters by the merchant rulers, and sent in search of a legendary sword of untold value to the new religion – their mission is treacherous. With only a young girl as guide, their quest will lead them on to the deep waters of the ′whale road′, toward the cursed treasure of Attila the Hun. And to a challenge that will test the very bond that holds them together.