The Lion Wakes

Robert Low

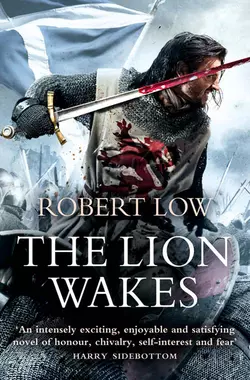

The first novel in The Kingdom Series as Robert Low moves from the Vikings to the making of Scotland.It is 1296 and Scotland is in turmoil. The old King, Alexander III, has died after falling off his horse one dark and stormy night. Scotland’s future is in peril. Edward I of England, desperate to keep control of his northern borders, arranges for John Baliol, a weak man who Edward knows he can manipulate, to take leadership of Scotland.But unrest is rife and many are determined to throw off the shackles of England. Among those men is Robert the Bruce, darkly handsome, young, angry and obsessed by his desire to win Scotland's throne. He will fight for the freedom of the Scots until the end.But there are many rival factions and the English are a strong and fearsome opponent. The Lion Wakes culminates in the Battle of Falkirk which proves to be the beginning of a rivalry that will last for decades…

ROBERT LOW

The Lion Wakes

Copyright

HarperFiction

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

Copyright © Robert Low 2011

Map © John Gilkes 2011

Robert Low asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Source ISBN: 9780007337910

Ebook Edition © 2011 ISBN: 9780007337934

Version: 2015-09-10

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it, while in some cases based on historical figures, are the work of the author’s imagination.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

To my wife, who is the sun on my shiny water: without her, I don’t sparkle

Contents

Cover (#ua77f4ee0-0005-582f-a301-c22552215641)

Title Page (#u6be4a317-b529-529a-9d17-fa377cd7fb01)

Copyright

Prologue

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Keep Reading (#litres_trial_promo)

Author’s Note

List of Characters

Glossary

Also by Robert Low

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Being a chronicle of the Kingdom in the Years of Trouble, written at Greyfriars Priory on the octave of Septuagisma, in the year of Our Lord one thousand three hundred and twenty-nine, 23rd year of the reign of King Robert I, God save and keep him.

In the year of Our Lord one thousand two hundred and ninety-six, the Scots decided they had had enough of King Edward lording it over them with his appointed Balliol king and so declared. The English came north with fire and sword and the Law of Deuteronomy at Berwick, so that the slaughter caused the name of that town to be used as a watchword and rallying cry for ever after.

The defeated King John Balliol was brought to Edward’s feet, to be stripped of crown and regalia, the proud heraldry of his rank torn from his surcote, so that he was known as Toom Tabard – Empty Cote – ever after. The coronation regalia of Scotland – the Holy Rood and the Stone of Scone – was seized, while the Great Seal was ceremonially snapped in half.

Then King Edward rode south, giving control of what he now thought of as his own lands to a governor, to keep the Scots in thrall to him.

A man does good work,’ he declared, washing his hands of the place, ‘when he rids himself of such a turd.’

But the Scots would not bow the knee . . . there was rebellion in the north under Moray, the east under Frazier, in the west under a brigand called Wallace. Scotland’s bishops were defiant. Sir William Douglas, who was called The Hardy for his boldness, and had defended Berwick against King Edward, was captured and then pardoned into the king’s peace on his promise to serve in the English army in France. Not long after, he slipped his bonds of oath and came to join the rebels.

Stung to action by this last, King Edward ordered his loyal subjects in Scotland to oppose these rebels and Robert Bruce the Younger, Earl of Carrick, was sent to Douglas Castle, to slight the fortress and take Sir William’s wife and bairns hostage.

But when the lion wakes, everyone must beware its fangs . . .

Prologue

Douglas, Lanark

Feast of St Drostan the Hermit, July 11, 1296

The worst part had been the dark. No moon, no stars, just the whispering of lost souls searching the wind for a way home, or a body to slither into for the memories of warm blood and life. There had been owls and he did not like owls, for they shrieked like Cyhiraeth, goddess of woodland streams, who wraiths through the dark screaming at those about to die.

Gozelo knew he should not allow himself to believe in such matters, being a good Christian, but his grandmother, old Frisian that she had been, had stuffed his head with such tales when he’d been younger. It only came out when he was ruffled and fretted and even God would have to admit that this country He had clearly forsaken did ruffle and fret.

Not the country so much as the Cloaked Man. Gozelo shivered and dragged his own cloak tighter round him, moving on into the silvered dawn and happy to see the light. He had been heading for Carnwath, held by the Lord Somerville – English or not, he was at least light and heat and, above all, safety – but the dark had put paid to that and Gozelo was now certain he had missed that place and was headed for Douglas.

He worried that a man limping in on foot would be sent away with a curse and a waved spear. A man on a horse had status while one slithering through the wet summer dawn on ripped shoes, with a cloak and tunic stained with hard travel, was nothing at all, even if he was a Flemish Master Mason from Scone. Not only that, Gozelo knew that Douglas was home to a nest of former rebels, who could not be trusted to keep out the ones he was sure now hunted him.

Something whirred and Gozelo started, looked wildly round and hurried on. He should never have taken the task but that old mastiff-faced Bishop Wishart had cozened him into it with flattery and promises of a fat purse. Not that making the piece had been difficult and Manon had seen to the carvings; Gozelo did not doubt now that the poor stone worker was dead.

Then the Cloaked Man had appeared with a cart and a worn horse for it and the Fleming realised that they were taking the original and leaving the cuckoo in its place. Manon, he had been told, was paid and gone already; that was when the chill, cold as altar stone, had sunk into his very soul.

‘We take this to Roslin,’ the Cloaked Man had said in French. ‘There you will be paid, both for your skill and to keep your mouth closed on this matter.’

If it had just been the Cloaked Man who had schemed all this, Gozelo would never have countenanced it at all – but it had been a bishop, no less, who had broached the subject of it. Gozelo thought Bishop Wishart a singular churchman at the time, had basked in the warm flattery and the promise of riches until the long struggle after the cart, the relentless wet – Christ in Heaven, was there no other weather in this Scotland? – and the gibber of his own fears had melted his resolve like gold in the assay. The Cloaked Man, grim as a wet cliff, became more and more sinister with each passing mile until, no more than a good walk from Roslin, the last of Gozelo’s courage crumbled and he ran.

The Cloaked Man had thought hard about it. Gone off without the fat purse and in a panic for his life, having finally worked out the possibilities. Aye, well – smart wee man that he was, he would work out more when his legs stopped long enough to let his mind start running. Like how to make up the lack of fat purse. He would head for Lanark and the English sheriff, Heselrig, where he would tell all he knew.

It was, the Cloaked Man noted, just as Wishart had said, calling him aside with a quiet: ‘If you trust os vulvae, then you are a fool. Go with God, my son.’

The Cloaked Man had to admit the bishop had been right, both about the Fleming’s character and how his mouth, wet-lipped and surrounded by a silly fringe of beard and moustache, did look like a woman’s part if you turned your head sideways. The Latin of it, os vulvae, the Cloaked Man decided, sounded better than the English – cunt face.

Of course, the Cloaked Man reasoned, clucking the weary pony up to the castle at Roslin, this Fleming may just head on to Dumfries and the English border. He was a Master Mason, after all, and would not be short of work for long.

Sir William Sientcler, the Auld Templar of Roslin, gave him a good, fast hobin horse and a sharp, meaningful glance when this had all been laid out to him.

‘Mak’ siccar,’ he said and the Cloaked Man nodded. He would make sure.

Gozelo could see the faint lights in the dark and almost sobbed with the relief of it, for he was now close to Douglas and could find shelter there before going on to Lanark. He would tell all he knew, he thought viciously, for what the Cloaked Man had put him through. He had convinced himself that he had been right to run before he had been black murdered in the dark. He would never return to this country again and would tell all he knew to the English, even after what they had done to the Flemings – some of them kin – in Berwick. They would pay, too and offset the loss of the promised purse. What was a silly stone to him, after all?

The shape rose up from behind the last fringe of trees leading to the water meadow that ran down to the shrouded bulk of the fortress and the so-near lights. Gozelo screamed, high as an owl, but it was all too late.

‘You went off without your due,’ the Cloaked Man said mildly and Gozelo fell back, babbling wildly, in French, English – any language that came to him. He was only vaguely aware of his bowels running down his leg, his mind a mad whirl of pleas that his mouth could not get out quickly enough.

‘You’ll say nothing?’ the Cloaked Man repeated, catching one of them as it spewed out, and saw the Fleming nod so wildly it seemed his head would fly off.

The Cloaked Man nodded sympathetically, then reached up with both hands to draw back the hood and show himself to the moon. The pallid light of it did nothing for his face and made the four-sided sliver of steel in one fist wink; Gozelo shrieked so high only dogs could hear him.

‘Best mak’ siccar,’ said the Cloaked Man into the Fleming’s bewilderment, stepping close and punching once; Gozelo leaned against him like a spent lover, then was gently slid to the mulch and the undergrowth.

The Cloaked Man wiped the dagger clean on the Fleming’s cloak, took what he needed from the unresisting corpse and left, leading the horse until he was sure he was clear away.

It was, he suddenly realised, the day after Longshanks had decreed for all Scotland’s community of the realm to meet at Brechin and witness what happened to a king who defied English Edward.

There had been, no doubt, humiliation and lies and vicious-ness. Edward would already have packed up the Rood and the Seal and the Stone as he had threatened, stripping both King John Balliol and kingdom of authority.

But Longshanks did not have all of Scotland in his grasp – one small part of the Kingdom had been taken from his fist.

The Cloaked Man smiled, warmed by the thought even as the summer mirr soaked him.

Chapter One

Douglas Castle, almost a year later

Vigil of St Brendan the Voyager, May 1297

The hounds woke Dog Boy as they always did, stirring and snuffing round him. Where there had been heat was suddenly cool and growing colder until it hooked him, shivering, from sleep.

At his movement, the dogs were round him, tongues lolling, panting fetid breath in his face, whining with hopeful looks and fawning eyes to be fed. They knew the routine of the day as well as Dog Boy – better, according to the Berner’s right-hand, Malk.

Dog Boy struggled up, speeding the process as the cold air chewed him. He pulled straw from his hair and clothes, fumbled for his pattens and stumbled in the half-dark of the kennels, a long, low building of wattle and daub with timber pillars. There was no light for fear of fire and the rear wall was solid, cold stone, part of the brewhouse; the only light dappled through the chinks in the daub on to the straw floor, which stank as it did every morning.

He found a rough wool over-tunic on a hook near the leashes, pulled it over his head and fumbled his arms through the holes, blowing on his hands for it was cold just before the dawn. Someone coughed; heads appeared, dark knobs surfacing through the straw and the other kennel-lads struggled into a new day. The dogs whined and whimpered, wriggled and circled endlessly, tails working furiously, wanting fed.

‘Soft, soft,’ Dog Boy soothed. ‘Quietly. It won’t be long.’

Unless there was a hunt, of course, in which case the dogs would not be fed, for full bellies made poor runners and the runners were the hounds he, with a handful of other lads, was responsible for. Raches and limiers, they were, about thirty all told, and they circled and whined while the other hounds, partitioned off to keep them from each other’s throat, started up a hoarse, howling bark.

‘Swef, swef,’ Gib called out to silence them, showing off the French he had learned from Berner Philippe. The dogs ignored him and Dog Boy smiled to himself – the limiers were English Talbots, white sleuthhounds, all nose and no stamina; Dog Boy thought it unlikely they would know any French. The raches were all colours, Silesian-bred hounds forming the bulk of the pack and made for long running. Once the limiers marked the trail, the raches would follow relentlessly until they brought the prey to bay or dropped.

He thought it unlikely any of them would understand French – if dogs understood any language at all – but France was the place thought to be the home of hunting and so all the hounds were given their French names and the head houndsman was a Frenchman, given his title in French - berner. Yet the prey they hunted here was the same – hart, hind and boar, all the preserve of the Dale, the Water and beyond, the lands given by God and King into the hands of the Douglas.

Beyond the thin partition, the other boys stirred as the alaunts and levriers bayed and howled. Dog Boy shivered and it was not from the cold: there were twenty levriers in there, fighting grey gazehounds with cold eyes and snarls. Yet even they balked and put their tails down when the strangers, two great rough-coated and huge deerhounds, curled a leathery lip.

The levriers were capable of running down and tackling a young, velvet-horned hart or a doe, the alaunts could tackle a good stag if it had been brought to bay, but only the deer-hounds could run a prime stag into the ground and still have the wind left to drag it down.

Douglas had no deerhounds, so it came as a shock to see this pair arriving with Sir Hal of Herdmanston and his riders. It had seemed to Dog Boy that there were a lot of riders for a simple hunting party, but he had been put right on that by Jamie and others – Sir Hal had come in the guise of a hunting party, sent by his father to hold to the promise they’d made to the Douglas fortalice to defend it in time of threat. There was no larger a threat, it had seemed, than the Lord Bruce of Carrick and his men, come to punish the Lady and her sons for her husband’s rebellion against the English King Edward.

It had come as a shock to Dog Boy to see all those men – more folk than he had ever seen in his life before – flowing round the castle like spilled oil. It was even more a shock to see how unruly the Herdmanston dogs were, so that the wolf-howls of them set every hound in Douglasdale off. Berner Philippe had been furious – but, to everyone’s surprise, the sight and smell of Dog Boy had calmed the two great beasts almost at once.

‘This one is Mykel,’ Master Hal had told him, and the dog had looked at Dog Boy with great, limpid eyes. ‘It means great, an old Lothian word. The other is called Veldi, which means power in the same tongue.’

Dog Boy nodded, breathless with the attention of the towering, smiling Hal and his towering, smiling crew, with names like Bangtail Hob and Ill Made Jock. Veldi, pink tongue lolling from between the white reefs of its teeth, looked at Dog Boy, the blue-brown eyes unwinking, and he felt the sheer heartleap of surety that these dogs were angels in disguise.

He tried to say as much, but could only manage ‘angels’, which made the giants laugh. One clapped him on the shoulder, almost driving him into the ground with the strength of it.

‘Angels, is it? Wee lad of pairts you, are ye not?’ this one said – Dog Boy had heard the others call him Tod’s Wattie. ‘Ye’ll chirrup different first time these hoonds of hell mak’ ye birl yer hocks in the glaur.’

From his bitterness, Dog Boy knew the dogs had somersaulted Tod’s Wattie into mud at least once; he could have sworn Mykel winked at him and he laughed, which made Tod’s Wattie scowl and all the others slap their thighs at his expense.

Sir Hal, grinning, had told him to take good care of his pets and Dog Boy had looked up into the old-young face, bearded and with eyes like sea haar, and loved the man from that moment; Mykel nudged a rough muzzle under his arm and stared at him with huge blue-brown eyes.

Once, on the day he had arrived in Douglas, Dog Boy had seen a hound as big as Mykel. A wolfhound, he had learned, rough-coated and big as a pony it seemed – but Dog Boy knew that he had been smaller then and had an idea that the deerhounds were even longer in the leg.

That animal had died when Dog Boy was eight, two years after his mother, walking proud and desperate, had shepherded him through the gatehouse of this place, which had been wooden then. On it had hung the Douglas shield, with its three silver stars – mullets, Dog Boy had been told, though he could not see that they looked like fish. He now knew – because Jamie Douglas had told him – that it came from the French, molette, which was a six-arrayed star.

Jamie, despite their differences in rank, was his friend and could read and knew where France lay. Dog Boy could not read at all and had no idea even where England was and a vague idea that Scotland lay fairly close to Douglasdale.

He knew that the English of England had come to Douglasdale, all the same, for Jamie spoke of little else these days, bitter that his mother had given in without a fight; now the Carrick men swarmed inside and outside Douglas Castle and the Lord Bruce, young and certain of himself to the point of arrogance, had politely taken over, in the name of the English – even though he was not one.

The one certainty in Dog Boy’s life, the thing that he hugged to himself when everything else seemed to whirl like russet leaves in a high wind, was his age – eleven. He knew this because he heard his mother say it, knew her voice better than he did her face.

He could not remember his father, though he had a rag-edged memory of stumbling in the plough ruts behind a man making kissing sounds to two oxen which were not his own, watching the plough blade curve a wave out of the earth.

He could feel it yet between his naked toes, see the birds wheel and cry at the exposed beetles and worms. It had been his job to get to the worms first and tuck them safely back in the torn ground, for they were ploughers of the earth every bit as much as Man. He heard a voice say that and thought it might have been his father – but all that was gone, save for the moment when the great slab face of his da came down to his level, the crack-thumbed hands on either of his thin shoulders.

It had come at the moment after he had run across the fields clutching the rough bag with a slab of day-old porridge and two bannocks in it. Run like a deer to where his da stood with the oxen he was so proud of owning. No-one else had such a prize.

His da had looked at him for a long time and then crouched down into his face.

‘Tha runs fast as a wee dug,’ he said sadly. ‘Fast as any wee dug.’

The day after that his ma had walked him into the castle and stood looking at Berner. Dog Boy was ashamed these days that he could not quite remember his own ma’s face now, but he remembered her voice and the feel of her hand on the top of his combed head.

‘I have brung him,’ she said. ‘As Sire said I could, when he could run fast as the dugs. He is six.’

Since then, there had only been those stones and the dogs.

Malk, the Berner’s assistant, reckoned up Dog Boy’s age and marked it in the Rolls along with the birthing dates of all the hounds and their pedigrees. It did not matter to Dog Boy, for he did not know, that Malk could trace a hound’s lineage back through several generations and recorded Dog Boy only as a scion of ‘bound tenants’ from a huddle of cruck houses twenty miles away.

It would have been a surprise to Dog Boy to know that he had a name, too – Aleysandir, same as the king who fell off a Fife cliff and plunged the whole of Scotland into chaos in the year Dog Boy was born – but Dog Boy did not know any of that and had been Dog Boy for so long that he knew no other name now.

‘Get aff me, ye dungbags!’

The voice jerked Dog Boy guiltily back to the kennels; Gib was pushing dogs away and, beyond him, The Worm stretched and yawned noisily, straw sticking out from his unruly hair. Dog Boy scratched a fleabite and then half-crouched, his habitual pose at sudden noises and surprises, as the heavy door banged open, flooding in cold light and chill air.

‘Avaunt, whelps.’

Silhouetted briefly in the pale square light of the doorway, the figure paused slightly, then stepped in, flicking his dogwhip; the hounds knew him well and circled away from him, yet kept coming back, tails down, fawning and whimpering.

Berner Philippe had to stoop to avoid the low roof, though he was not tall. He wore a battered leather jack to protect the plain, stained-wool robe, itself worn to keep the pale-grey tunic clean from the dogs. He also wore his habitual sour sneer, which bristled his trimmed black beard.

‘Come on, come on, stir yourselves,’ he growled. ‘There’s work to be done – where is Gib?’

Gib stumbled forward, picking straw off himself and rubbing sleep from his eyes. He swept a bow, almost mocking, as he showed off his little command of French.

‘A votre service, Berner Philippe’

The scowl deepened a little as Philippe looked at him. This one was becoming too familiar by half. It wouldn’t do. He tongued the stump of a tooth, then forced a smile and patted the boy on the cheek.

‘Ah, lordling,’ he said lightly. ‘Such manners, eh?’

The others watched him caress Gib as he would do the dogs, chucking him under the chin, fondling behind one ear; it was as much part of the ritual of morning as waking, for Gib was the berner’s favourite.

There were six houndsmen under Berner Philippe. Together with the six piqueurs, the huntsmen, they considered themselves the true Disciples of Douglas, not the strutting men-at-arms, who numbered the same. If that were so, then Berner Philippe was St Peter, White Tam, the head piqueur was James, brother of Jesus, the Lady Eleanor was the Virgin Herself – and The Hardy was Christ in Person.

Thus was life arranged by Law and Custom, which is to say, by God.

‘Take five lads and clean this cesspit,’ said Philippe and looked from Dog Boy to Gib and back again. Then he nodded to Gib and watched as the boy shambled off to obey. He was getting bigger . . . too big, God’s Wounds. What had once been soft flesh was filling and hardening and, even to a nose used to stinks, Gib reeked more and more positively of dog every day.

Dog Boy stood, looking at the fetid straw as if there was a cunning picture in it, and Philippe wondered, as he had always done, why he had never taken to the lad. Too scrawny, probably. There was a new lad – Philippe’s head swung this way and that like a questing hound on a scent. What was his name . . . ? Hew, that was it. That was the name his parents had given him, but he was on the Rolls with an easily remembered nickname – a dog name, Falo, which meant ‘yellow’, and Philippe picked him out from the others by his cap of golden hair.

Disappointment. Too young – still, that blond hair, which spoke of decent ancestry implanted in the mongrel Scots, fell over the boy’s face as he gathered armfuls of stinking straw and Philippe’s groin tightened a little. Worth waiting for . . .

He caught sight of Dog Boy, edging, as always, into the shadows. Dog Boy felt more than saw the eyes fall on him and stopped, dull with despair.

‘You,’ Philippe said shortly, eyeing the thin-limbed, dark-eyed boy with the distaste he gave to all runts. ‘Mews. Gutterbluid wants you.’

Outside, the cold bit Dog Boy and he hugged himself, dragging himself to the mews across the expanse of Ward in a cold wind out of the charcoal sky. Dog Boy eyed the glowing coals where Winnie the smithwife was blowing life into the forge fire, sparks flying dangerously up to the stiffened thatch of the wagon shed and the great stretch of stables. Beyond was the palisade and ditch, the gatehouse, newly done in stone, and the wooden dovecote etched blackly against the slow, souring milk of a new dawn. Behind, the bulked towers and stone walls of the Keep humped up and lurked over him.

The forge flames flared and danced brief eldritch shadows up the wall of one tower, to the narrow cross-slit window of the chapel, where light glowed, the honey-yellow of tallow candles; Brother Benedictus, the Chaplain, was already at his devotions, murmuring so that Dog Boy was almost sure he heard the words he knew so well:

Domine labia mea aperies. Et os meum annunciabit laudem tuam. Deus in adiutorium meum intende.

Dog Boy, hurrying on past the bakehouse, already spewing stomach-gripping smells and smoke, muttered the expected response without thinking – Ave Maria, gracia plena. The rest of it followed him, circling faintly like a chill wind off the river – Gloria patri et filio et spiritui sancto. Sicut erat in principio et nunc et semper et in secula seculorum. Amen. Alleuya.

He went past the dovecote, with its steep little roof surmounted by a strange bird pecking its own chest, and saw Ferg the scullion fetching new loaves and grinning at him, for he knew the Latin words as well. Neither had a clear idea of what they meant and knew them by rote only.

Next to the bakehouse, the kitchen sheds were quiet and coldly pale, as were most of the buildings within the rough palisade separating the Ward from the Keep, where lay the Great Hall, the stables and barracks and some little gardens.

Somewhere, high up on the hourds, watchmen stamped and blew on their hands. Soon those wooden hoardings would be dismantled, for the need for them was gone now that the Lady had given in to the Carrick men.

There had been a moment of confusion a few days later when a new host appeared, smaller but no less fierce. Dog Boy had heard the leader of it hailed as the Earl of Buchan and Jamie had muttered that no-one was sure whether this Comyn lord was for or against King Edward.

Dog Boy had watched them arrive, with their banners and their shouting; it had been exciting for a while and he wondered if he would see fighting – but then it had all ended, just like that. It was a puzzle that the Lady of Douglas now treated the Invaders as Friends and the castle was crowded with them, while more were huddled in makeshift shelters all over the Ward and beyond.

‘Dog Boy,’ called a voice, and he turned to see Jamie stepping from the shadows. Dog Boy bowed and Jamie accepted it as his due, since he was The Hardy’s eldest, with black braies and a dagged hood, a fine knife in a sheath on his belt, good leather boots and a warm surcote.

He was of ages with Dog Boy, yet bigger and stronger because he trained with weapons and would one day take the three vows and become a knight. One day, too, he would become Jesus Christ, Dog Boy thought, when his father, The Hardy, died and left him the lordship of Douglas. Even now he was able to fly a tiercel gentle, a male peregrine, if he chose – the memory of where that bird roosted brought misery crashing back on Dog Boy.

‘Cold,’ Jamie offered with a grin. ‘Cold as a witch’s tit.’

Dog Boy grinned back at him. They were friends of a sort – even if Dog Boy wore worn, mud-coloured clothing and was of no consequence at all – because Jamie liked the dogs and had no mother, like Dog Boy. Dog Boy had questioned this once, because he had thought the Lady Eleanor was Jamie’s mother, but Jamie had put him on the straight road of that one.

‘My real mother was sent away,’ he said bluntly. ‘To a convent. This one is my father’s new woman and the sons he pupped on her are my stepbrothers.’

He turned and looked at Dog Boy then, savage as his tiercel.

‘But I am the heir and one day this will be mine,’ he added and Dog Boy had no doubt of it. It was what they shared, what cut through their stations. The same age, the same colouring, the same abandonment by ma and da. The same loneliness. It had all brought them together from the moment they could toddle and they had rattled around like two stones in a pouch ever since.

Both of them knew that changes were happening, all the same, as much to their rank as their bodies, and that unseen pressures were forcing them further and further apart. Dog Boy would never be anything more than he was now – Jamie would become a knight, like his father.

There had been no knights other than The Hardy in Douglas, though there had once been twenty men-at-arms, with stout jacks, swords and polearms. Now there were only six, for the rest were gone and Dog Boy felt the cold unease slide into him, the way it had done the year before when the four surviving men had carried a fifth in through the gate.

They also carried the news that The Hardy was imprisoned and all the other Douglas men were dead, together with some thousands of folk who had been living in Berwick when English Edward had captured it.

‘The blood came up ower the tops of my shoes,’ Thomas the Sergeant had told them, and he should know, for some of it was his and he wore the scar, raw as memory, down one side of his face. He had been the fifth man and, for a while, it looked as if he would die – but he was tough, folk said, hard as Sir William Douglas himself.

Jamie loved and feared his father in equal measure and the fact that Sir William had survived the siege and slaughter at Berwick and was fighting still, flooded his world – though Dog Boy did not quite understand all of it and Jamie explained it, as if schooling a hound.

It seemed that the Earl of Carrick, who was a young, dark Bruce called Robert, had arrived on orders from the English to punish the Lady because of her man’s siding with the uprisen Scots. The Lothian lord, the hard-eyed man with the big hounds, had come in the last drip of the candle to help the Lady defy this earl.

For reasons the Dog Boy could not quite grasp, he and the Lady had then surrendered to Earl Robert – but none of the dire consequences everyone else said was certain if you gave into Invaders had happened. Nothing much had happened at all, save that the Castle grew crowded.

Not long after that, another Earl had arrived at the gate, this one called Buchan. It seemed he and the Earl Robert did not care much for each other, but seemed to be on the same side. Which was not the one Sir William Douglas stood on.

Dog Boy had no clear idea why this Earl Buchan had arrived at all, but was surprised to find that the fox-haired Countess who had arrived with Earl Robert was, in fact, the wife of the Earl called Buchan. It was a whirl of leaves in a high wind to the Dog Boy and, finally, Jamie saw his audience’s interest slipping. He spasmed with childish irritation.

‘From your point of view, I suppose this war is only an annoyance of rolling maille in a barrel of sand to clean it, or having to practise archery.’

Dog Boy said nothing, aware his friend was angry and not quite sure why. There was guilt, too – he was supposed to attend archery practice like all the lower orders, but seldom did and no-one cared if the runty Dog Boy never turned up.

It didn’t bother him, missing out on the butts, for there had never been an enemy here until the Invaders – and they had ended up Friends. Yet, slowly, Dog Boy was becoming aware of a tremble in the fabric of life, could hear the cracking of the stones of Douglas Keep.

‘Faugh – you stink today,’ Jamie said suddenly, wrinkling his nose as the wind changed. ‘When did you wash last?’

‘Fair Day,’ Dog Boy replied indignantly. ‘Same as the rest, wi’ real soap and rose petals in the watter.’

‘Fair Day,’ Jamie exploded. ‘That was months since – I had a wash only last week, in a tub of piping hot water with Saracen scented soap.’

He winked what he thought was in knowing, lecherous fashion.

‘And a wench to scrub my back – eh?’

‘I dinna think your lady mother would suffer that,’ Dog Boy answered doubtfully, aware of the mysteries of dog and bitch but not yet sure how it translated to the mumblings and groans he heard sometimes in the night. He was aware, too, that there was a Rule about women. In Douglas there was a Rule about almost everything.

‘The Lady Eleanor is not my mother,’ Jamie answered, stiff and haughty. ‘She is my father’s wife.’

He frowned, all the same, for Dog Boy was right and yet Jamie had seen matters and heard more which only confused him about what was permitted and what was not. There were women in the castle – notably Agnes in the castle kitchen and some tirewomen for his stepmother and now the Countess of Buchan, who laughed a lot and had wild hair a wimple could not keep in check. She stayed in her own tower rooms, though, while her husband scowled in his proud, striped panoply in the Ward, and that was strange.

‘I’m off to get some bread,’ Jamie decided, throwing the matter over his shoulder. ‘Do you want some?’

Dog Boy’s mouth watered. The birds could wait; the smell of baking bread, newly turned from the ovens, brought both their heads up, sniffing and salivating.

‘Dog Boy!’

The voice slashed them apart, a soft rasp of sound like a blade drawn down a rough wall. Both boys shrank at the sound and turned to where the Falconer had appeared, as if sprung from the ground. He gathered his marten coat round him, wore his marten hat with its single eagle feather and if there were three other items of value in the entire world, it was said, Falconer did not know of them.

Those who said that did not call him Gutterbluid where he could hear it, since it meant ‘low-born whelp’. His real name was Sib, according to some, and he had the name Gutterbluid because it was one you gave to folk born in Peebles when you wanted to annoy them. No-one wanted to annoy Sib, so they simply called him Falconer and no-one liked him; Dog Boy liked him least of all.

‘You are dallying, boy,’ Falconer sibilated. Jamie, recovering, struck a shaky air of nonchalance, aware that he should try to conquer his fears if he was to be a knight.

‘I was addressing him, Falconer,’ he declared, then wilted beneath the black gaze of the man, whose eyes burned from his lean, brown face. No wonder, Jamie thought wildly, folk think he is a Saracen.

Falconer looked the boy up and down. Lisping pup, he thought. Falconer had more skills, more intelligence and more right to dignity – yet this little upstart was noble born and Falconer could only aspire to looking after what mean birds they could afford.

He wanted to cuff the boy round the ear but knew his place and the price for stepping out of it. So he bowed instead.

‘Your pardon, young master. When you are done, I will have my lure.’

Dog Boy saved Jamie from further torture by bobbing a bow to him and scuttling past Falconer towards the mews, where he slipped on the badger-skin gloves, and hunched, waiting. Jamie and Falconer stared at each other for a moment longer until the last of Jamie’s courage melted like rendered grease. Falconer, satisfied, curled a smile on one lip, bowed again and strode after Dog Boy.

The mews was dark, fetid with droppings, filled with a sound like great hanging banners fluttering faintly in a wide hall; the birds, a dozen or so, moving softly on their perches, claws scraping. Each bird stood in its own niche, or on a perch, motionless as a corbel carving, blind knights in plumed hoods. Dog Boy stepped in, basket held in the crook of one arm, a bloody little feathered body in one gloved hand.

He drew in a breath, heavy with the rank must of the birds, they scented him, exploding in a frenzy of frantic hunger, shrieking and screaming. The air was filled with the mad beating of wings and a sleet of feathers. They screeched and leaped to the furthest ends of the jesses, flinging themselves in desperate desire at Dog Boy, red-eyed and wild, battering him furiously.

Dog Boy winced and shoved the food at them, staggering down the passage between them, unable to strike back for fear of what Falconer would do, trying to protect himself from the wind and the storm of hate. Jamie’s gerfalcon careered off its perch and could not find its way back. One frenzied bird lashed out with a talon and scored a hit on the back of Dog Boy’s wrist as the glove slipped.

A hand fell on the blizzard-blinded youth, gripping him by the shoulder and pulling him from the whirl of feathers and claws and endless, endless shrieks. He was flung out the door to land in a sobbing heap and, after a while, got enough breath back to sit up, wiping tears and feathers from his face. There was a long, scarlet trail on the back of one hand and he sucked it, then slithered off the gloves, seeing the new, tufted rents in them.

He heard Falconer – soft, soft, he was saying. My beauties, all over now. Soft, soft, my children.

A shadow fell on Dog Boy and he jerked, started to wriggle away. Falconer . . .

It was Jamie, his mouth set in a stitched line. He held out a piece of bread without a word and Dog Boy took it. It steamed, fresh from the oven and was hot in Dog Boy’s mouth.

‘Finished?’

Dog Boy nodded, unable to speak, and Jamie held out his hand, took Dog Boy’s wrist and hauled him up. Together, they sprinted for the smithy, wriggling up to the forge block, picking metal shavings and bent nails from under their bodies.

Winnie the Smithwife, short, stocky and dark as a north dwarf, stuck her fire-reddened face, hair braided into thick plaits against flying sparks, down into their corner and grinned. She passed them down some small beer without a word, for she liked their being there, like little mice, while she pounded metal into shape. Warmed by the food and the fire, Dog Boy began to feel better.

‘Not much,’ Jamie said, studying Dog Boy’s new wound.

‘When I am lord here,’ he added, ‘this will end.’

Neither of them spoke after that, for there was nothing to say. This was Dog Boy’s other task in life – the birds were starved and then fed by him and only him. If they hunted and one was lost, Dog Boy was sent out to find it. No matter how much it had eaten, or whether the exultant joy of freedom gripped it, the sight and smell of Dog Boy, whirling bait on the end of a line, would make the bird stoop and be recaptured.

Hal saw them scamper as he passed, padding silent, on his way to see to the Herdmanston men and make sure they toggled their lips on any mention of what they had seen or heard about the Countess Isabel of Buchan and the young Bruce.

He did not like Gutterbluid, or the lure he made of the kennel laddie, and knew it for a punishment he suspected had been ordered by the Lady Eleanor. He suspected he knew why, too – but such was the way of the world, decreed by Law and Custom and, therefore, by God.

It did not help that the world was birling in ever more strange jigs these days, none stranger than finding that he had been sent to defend Douglas rights only to find his Roslin kin – and liege lord the Auld Templar Sir William Sientcler – riding with Bruce.

Hal had known that before he had set off, scraping almost every man Herdmanston possessed on the orders of his father and despite protests. There was scarce a man left to guard the yett of their own wee tower fortalice, but his father, rheumy eyed and grit-voiced, had thumped his shoulder when he had voiced this.

‘I hold to the promise made that the Sientclers of Herdmanston would defend the rights of the Douglas. There was no wee notary’s writing in it concerning gate guards or our kin’s involvement, lad.’

There was considerable relief, then, when the Lady Eleanor took Hal’s advice and surrendered to The Bruce and his Carrick men without demure, though she had scowled and all but accused him of treachery because the Auld Templar stood on the other side.

Hal had swallowed that and convinced her, sighing with relief when the gates were opened and young Bruce, the Earl of Carrick rode in and never so much as cocked an eye at the Lady’s truculence.

‘I was sent by my father,’ he told her, his bottom lip stuck out like a petulant shelf, ‘who was himself instructed by King Edward to punish Douglas for the rebellion of Sir William.’

He leaned forward on the crupper of the great horse while the Ward milled and fumed with men, some of them only half aware of the Lady Eleanor’s straight-backed defiance and the young Bruce’s attempts to be polite and reasonable.

‘Your man quit Edward’s army without permission, first chance he had,’ he declared flatly. ‘Now God alone knows where he is – but you could pick Sir Andrew Moray’s north rebellion as a likely destination. I have come from Annandale to take this place and slight it, Lady, as punishment. That I have not knocked it about too much, while putting you in my protection, means my duty is done, while you and your weans are safe.’

The rebel Scots may cry Bruce an Englishman, Hal thought, but the real thing would not have been so gentle with the Lady Eleanor of Douglas – but she was a fiery beacon of a woman and not yet raked to ashes by this sprig of a Bruce.

‘You do it because my husband’s wrath would chase ye to Hell if ye did other. As well young Hal Sientcler’s kinsman was with you, my lord Earl. A Templar guarantee. My boys and I thank you for it.’

The Auld Templar, his white beard like a fleece on his face, merely nodded but the young Bruce’s handsome face was spoiled by the pet of his lip at this implication that the Bruce word alone was suspect; seeing the scowl, the Lady of Douglas smiled benignly for the first time.

It was not a winsome look, all the same. The Lady Eleanor, Hal thought, has a face like a mastiff chewing a wasp, which was not a good look for someone whose love life was lauded in song and poem.

She was a virgin – Hal knew this because the harridan swore she was pure as snow on The Mounth. He didn’t argue, for the besom was as mad as a basket of leaping frogs – but if God Himself asked him to pick out the sole maiden in a line of women he would never, ever, have chosen Eleanor Douglas, wife of Sir William The Hardy.

Her fierce claim was supposed to make her legitimately bairned. That, Hal thought, would also make her two sons, Hugh and Archie, children of miracle and magic since she and The Hardy had been lovers long before they were kinched by the Church. Then The Hardy had abducted her, sent his existing wife to a convent and married Eleanor, risking the wrath of everyone to do it.

Not least her son, Hal thought, seeing the young Jamie standing, chin up and shoulders back beside his stepmother. Hal watched him holding his tremble as still as could and felt the jolt of it, that loss. Like his John, he thought bleakly. If Johnnie had lived he would be the age this boy is now.

The memory dragged him back to the Ward and the sight of Jamie and the kennel lad scurrying for the smithy, and he felt the familiar ache.

Sim Craw, following Hal into the blued morning, also saw the boys slip across the Ward – and the cloud in Hal’s eyes, like haar swirling over a grey-blue sea. He knew it for what it was at once, since every boy Hal glanced at reminded him of his dead son. Aye, and every dark-haired, laughing-eyed woman reminded him of his Jean. Bad enough to lose a son to the ague, but the mother as well was too much punishment from God for any man, and the two years since had not balmed the rawness much.

Sim had little time for boys. He liked Jamie Douglas, all the same, admired the fire in the lad the way he liked to see it in good hound pups. No signs and portents in the sky on the night James Douglas was born, he thought, just a mother suddenly sent away and a life at the hands of The Hardy, hard-mouthed, hard-handed and hard-headed. Unlike his step-siblings, quiet wee bairns that they were, James had inherited a lisp from his ma and the dark anger of his da, which he showed in sudden twists of rage.

Sim recalled the day before, when Buchan had arrived and everyone flew into a panic, for here was the main Comyn rival to the Bruces standing at the gates and no-one was sure whether he was in rebellion, since he should not be here at all.

Worse still, his wife was here, thinking her husband a few hundred or more good Scotch miles away with English Edward’s army heading for the French wars, so leaving her free for dalliance with the young Bruce.

So there had been a long minute or two when matters might have bubbled up and Sim had spanned his monstrous latchbow. The young Jamie, caught up in the moment, had raised himself on the tips of his toes and lost entirely the usual lisp that affected him when he roared, his boy’s body shaking with the fury in it, his child’s face red.

‘Ye are not getting in. Ye’ll all hang. We will hang you, so we will.’

‘Weesht,’ Sim had ordered and slapped the boy’s shoulder, only to get a glare in return.

‘Ye cannot speak to me like that,’ he spat back at Sim. ‘One day I will be a belted knight.’

There was a sharp slap and the boy yelped and held his ear. Sim put his gauntlet back on and rested his hand on the stock of his latchbow, unconcerned.

‘Now I have made ye a belted knight. If ye give your elders mair lip, Jamie Douglas, ye’ll be a twice belted knight.’

He mentioned the moment now to Hal, just to break the man’s gaze on the place where the boys had been. Jerked from the gaff of it, Hal managed a wan smile at Sim’s memory.

‘Bigod, I hope he has no good remembrance of it when he comes into his own,’ he said to Sim. ‘You’ll need that bliddy big bow to stop him giving ye a hard reply to that ear boxing.’

A sudden blare of raucous shouting snapped both their heads round and the great slab face of Sim Craw creased into one large frown.

‘Whit does he require here?’ he asked, and Hal did not need to ask the who of it, for the most noise came from in and around the great striped tent of the Earl of Buchan.

‘His wife, I shouldn’t wonder,’ Hal answered dryly, and Sim laughed, soft as sifting ashes. Somewhere up there, Hal thought, glancing up to the dark tower, is the Countess of Buchan, the bold and beautiful Isabel MacDuff, keeping to the lie that she had coincidentally turned up to visit Eleanor Douglas.

Buchan, it seemed, was the one man in all Scotland who did not know for sure that the young Bruce and Isabel were rattling each other like stoats and had been lovers, as Sim said, since the young Bruce’s stones had properly dropped.

For all the humour in it, this was no laughing matter. The Earl of Buchan was a Comyn, a friend to the Balliols of Galloway, who were Bruce’s arch-rivals. A Balliol king had been appointed four years before by Edward of England – and then stripped of his regalia only last year when he proved less than biddable. Now the kingdom was in turmoil, ostensibly ruled directly from Westminster.

But all the old kingdom rivalries bubbled in the cauldron of it and it would not take much for it all to boil over. Finding an unfaithful wife with her legs in the air would do it, Hal thought.

A piece of the dark detached itself and made both men start; a wry chuckle made them drop their hands from hilts, half ashamed.

‘Aye, lads, it is reassuring to a man’s goodwill of himself that he can make two such doughty young warriors afraid still.’

The dark-clothed shape of the Auld Templar resolved into the familiar, his white beard trembling as he chuckled. Hal nodded, polite and cautious all the same for the Auld Templar represented Roslin and the Sientclers of Herdmanston owed them fealty.

‘Sir William. God be praised.’

‘For ever and ever,’ replied the Templar. ‘If ye have a moment, the pair of ye are requested.’

‘Aye? Who does so?’

Sim’s voice was light enough, but held no deference to rank. The Auld Templar did not seem put out by it.

‘The Earl of Carrick,’ he declared, which capped matters neatly enough. Meekly, they followed the Auld Templar into the weak, guttering lights of hall and tower.

The chamber they arrived in was well furnished, with a chest and a bench and a chair as well as fresh rushes, and perfumed with a scatter of summer flowers. Wax tapers burned honey into the dark, making the shadows tall and menacing – which, Hal thought, suited the mood of that place well enough.

‘Did you see him?’ demanded Bruce, pacing backwards and forwards, his bottom lip thrust out and his hands wild and waving. ‘Did you see the man? God’s Wounds, it took me all of my patience not to break my knuckles on his bloody smile.’

‘Very laudable, lord,’ answered a shadowed figure, sorting clothing with an expert touch. Hal had seen this one before, a dark shadow at the Bruce back. Kirkpatrick, he recalled.

Bruce kicked rushes and violets up in a shower.

‘Him with his silver nef and his serpent’s tongue,’ he spat. ‘Did he think the salt poisoned, then, that he brings that tooth out? An insult to the Lady Douglas, that – but there is the way of it, right enough. An insult on legs is Buchan. Him and his in-law, the Empty Cote king himself. Leam-leat. Did you hear him telling me how none of us would have done any better than John Balliol? Buchan – tha thu cho duaichnidh ri earr airde de a’ coisich deas damh.’

‘I did, my lord,’ Kirkpatrick replied quietly. ‘May I make so bold as to note that yourself has also a nef, a fine one of silver, with garnet and carnelian, and a fine eating knife and spoon snugged up in it. Nor does calling the Earl of Buchan two-faced, or – if I have the right of it – “as ugly as the north end of a south-facing ox” particularly helpful diplomacy. At least you did not do it to his face, even in the gaelic. I take it from this fine orchil-dyed linen I am laying out that your lordship is planning nocturnals.’

‘What?’

Bruce whirled, caught out by the casual drop of the last part into Kirkpatrick’s dry, wry flow. He caught the man’s eye, then looked away and waved his hands again.

‘Aye. No. Perchance . . . ach, man, did I flaunt my garnet and carnelian nef at him? Nor have I a serpent’s tongue taster, which is not an honourable thing.’

‘I have a poor grasp o’ the French,’ Sim hissed in Hal’s ear. ‘Whit in the name of all the saints is a bliddy nef?’

‘A wee fancy geegaw for holding your table doings,’ Hal whispered back out of the side of his mouth, while Bruce rampaged up and down. ‘Shaped like a boatie, for the high nobiles to show how grand they are.’

It was clear that Bruce was recalling the dinner earlier, when he and Buchan and all their entourage had smiled politely at one another while the undercurrents, thick as twisted ropes, flowed round and between them all.

‘And there he was, talking about having Balliol back,’ Bruce raged, throwing his arms wide and high with incredulity. ‘Balliol, bigod. Him who has abdicated. Was publicly stripped of his regalia and honour.’

‘A shame-day for the community of the realm,’ growled the Auld Templar from the shadows, heralding the eldritch-lit face that shoved out of them. It was grim and worn, that face, etched by things seen and matters done, honed by loss to a runestone draped with snow.

‘From wee baron to King of the Scots in one day,’ Sir William Sientcler added broadly, stroking his white-wool beard. ‘Had more good opinion of himself than a bishop has wee crosses – now he is reduced to ten hounds, a huntsman and a manor at Hitchin. He’ll no’ be back, if what he ranted and raved when he left is ony guide. John Balliol thinks himself well quit of Scotland, mark me.’

‘I am bettering,’ Bruce said with a wan smile. ‘I understood almost all of that.’

‘Aye, weel,’ replied Sir William blithely. ‘Try this – if ye don’t want the same to choke in your thrapple, mind that it was MacDuff an’ his fine conceit of himself that ruined King John Balliol, with his appeals for Edward to grant him his rights when King John blank refusit.’

Bruce waved one hand, the white sleeve of his bliaut flapping dangerously near a candle and setting all the shadows dancing.

‘Aye, I got the gist of that fine – but MacDuff of Fife was not the only one who used Edward like a fealtied lord and undermined the throne of Scotland. Others carried grievances to him as if he was king and not Balliol.’

Sir William nodded, his white-bearded blade of a face set hard.

‘Aye well – the Bruces never did swear fealty to John Balliol, if I recall, and I mention MacDuff,’ he replied, ‘less because he has raised rebellion in Fife, and more because ye are trailing the weeng with his niece and about to creep out into the dark to be at her beck an’ call, with her own man so close ye could spit on him.’

He met Bruce’s glower with a dark look of his own.

‘Doon that road is a pith of hemp, lord.’

The silence stretched, thick and dark. Then Bruce sucked his bottom lip in and sighed.

‘Trailing the weeng?’ he asked.

‘Swiving . . .’ began Sir William, and Kirkpatrick cleared his throat.

‘Indulging in an illicit liaison,’ he said blandly, and Sir William shrugged.

Bruce nodded, then cocked his head to one side. ‘Pith of hemp?’

‘A hangman’s noose,’ Sir William declared in a voice like a knell.

‘Serpent’s tongue?’ asked Sim, who had been bursting to ask about it since he had heard it mentioned earlier; Hal closed his eyes with the shock of it, felt all the eyes swing round and sear him.

After a moment, Bruce sat down sullenly on the bench and the tension misted to shreds.

‘A tooth for testing salt for poison,’ Kirkpatrick answered finally. He had a face the shadows did not treat kindly, long and lean as an edge with straight black hair on either side to his ears and eyes like gimlets. There was greyness and harsh lines like knifed clay in that face, which he used as a weapon.

‘From a serpent?’ Sim persisted.

‘A shark, usually,’ Bruce answered, grinning ruefully, ‘but folk like Buchan pay a fortune for it in the belief it came from the one in Eden.’

‘We are in the wrong business, sure,’ Sim declared, and Hal laid a hand along his forearm to silence him. Kirkpatrick saw it and studied the Herdmanston man, taking in the breadth of shoulder and chest, the broad, slightly flat face, neat-bearded and crop-haired.

Yet there were lines snaking from the edge of those grey-blue eyes that spoke of things seen and made him older. What was he – twenty and five? And nine, perhaps? With callouses on his palms that never came from plough or spade.

Kirkpatrick knew he was only the son of a minor knight from an impoverished manor, an offshoot of nearby Roslin, which was why Sir William was vouching for him. The Auld Templar of Roslin had lost his son and grandson both at the battle near Dunbar last year. Captured and held, they were luckier than others who had faced the English, fresh from bloody slaughter at Berwick and not inclined to hold their hand.

Neither Sientcler had yet been ransomed, so the Auld Templar had gained permission to come out of his austere, near-monkish life to take control of Roslin until one or both were returned.

‘Sir William tells me you are like a son to him, the last Sientcler who is young, free, with a strong arm and a sensible head,’ Bruce said in French.

Hal looked at Sir William and nodded his thanks, though the truth was that he was unsure whether he should be thankful at all. There were children still at Roslin – two boys and a girl, none of them older than eight, but sprigs from the Sientcler tree. Whatever the Auld Templar thought of Hal of Herdmanston it was not as an heir to supplant his great-grandchildren at Roslin.

‘It is because of him I bring you into this circle,’ Bruce went on. ‘He tells me you and your father esteem me, even though you are Patrick of Dunbar’s men.’

Hal glanced daggers at Sir William, for he did not like the sound of that at all. The Sientclers were fealtied to Patrick of Dunbar, Earl of March and firm supporter of King Edward – yet, while the Roslin branch rebelled, Hal had persuaded his father to give it lip service, yet do nothing.

He heard his father telling him, yet again, that people who sat on the fence only ended up with a ridge along their arse; but Bruce and the Balliols were expert fence-sitters and only expected everyone else to jump one side or the other.

‘My faither,’ Hal began, then switched to French. ‘My father was with Sir William and your grandfather in the Crusade, with King Edward when he was a young Prince.’

‘Aye,’ answered Bruce, ‘I recall Sir John. The Auld Sire of Herdmanston they call him now, I believe, and still with a deal of the lion’s snarl he had when younger.’

He stopped, plucking at some loose threads on his tight sleeve.

‘My grandfather only joined the crusade because my own father had no spine for it,’ he added bitterly.

‘Honour thy father,’ Sir William offered up gruffly. ‘Your grand-da was a man who loved a good fecht – one reason they cried him The Competitor. Captured by that rebellious lord Montfort at Lewes. It was fortunate Montfort was ended at Evesham, else the ransom your father had to negotiate would have been crippling. Had little thanks for his effort, if I recall.’

Bruce apologised with a weary flap of one hand; to Hal this seemed an old rigg of an argument, much ploughed.

‘You came here with two marvellous hounds,’ Bruce said suddenly.

‘Hunting, lord,’ Hal managed, and the lie stuck in his teeth a moment before he got it out. Bruce and Sir William both laughed, while Kirkpatrick watched, still as a waiting stoat.

‘Two dogs and thirty riders with Jeddart staffs and swords and latch-bows,’ Sir William replied wryly. ‘What were ye huntin’, young Hal – pachyderms from the heathen lands?’

‘It was a fine enough ruse to get you into Douglas the day before me,’ Bruce interrupted, ‘and I am glad you saw sense in obeying your fealtied lord over it, so that we did not have to come to blows. Now I need your dogs.’

Hal looked at Sir William and wanted to say that, simply because he had seen sense and trusted to the Auld Templar’s promises, he was not following after Sir William in the train of Robert Bruce. That’s what he wanted to say, but could not find the courage to defy both the Auld Templar and the Earl of Carrick at one and the same time.

‘The dugs – hounds, lord?’ he spluttered eventually and looked to Sim for help, though all he had there was the great empty barrel of his face, a vacant sea with bemused eyes.

Bruce nodded. ‘For hunting,’ he added with a smile. ‘Tomorrow.’

‘To what end?’ Sir William demanded, and Bruce turned fish-cold eyes on him, speaking in precise, clipped English.

‘The kingdom is on fire, Sir William, and I have word that Bishop Wishart is come to Irvine. That old mastiff is looking to fan the flames in this part of the realm, be sure of it. The Hardy has absconded from Edward’s army and now I find Buchan has done the same.’

‘He has a writ from King Edward to be here,’ Kirkpatrick reminded Bruce, who gave a dismissive wave.

‘He is here. A Comyn of Buchan is back. Can you not feel the hot wind of it? Things are changing.’

Hal felt the cold sink of that in his belly. Rebellion. Again. Another Berwick; Hal caught Sim’s eye and they both remembered the bloody moments dissuading Edward’s foragers away from the squat square of Herdmanston following the Scots defeat at nearby Dunbar.

‘So we hunt?’ Sir William demanded with a snort, hauling his own tunic to a more comfortable position as he sat – Hal caught the small red cross on the breast that revealed the old warrior’s Templar attachment.

‘We do,’ Bruce answered. ‘All smiles and politeness, whilst Buchan tries to find out which way I will jump and I try not to let on. I know he will not jump at all if he can arrange it – but if he does it will be at the best moment he can manage to discomfort the Bruces.’

‘Aye, weel, your own leap is badly marked – but you may have to jump sooner than you think,’ Sir William pointed out sharply, and Bruce thrust out his lip and scowled.

‘We will see. My father is the one with the claim to the throne, though Longshanks saw fit to appoint another. It is how my father jumps that matters and he does not so much as shift in his seat at Carlisle.’

‘Which gives you a deal of freedom to find trouble,’ Hal added, only realising he had spoken aloud when the words were out.

He swallowed as Bruce turned the cold eyes on him; it was well known that the tourney-loving, spendthrift Earl of Carrick was in debt to King Edward, who had so plainly taken a liking to the young Bruce that he had been prepared to lavish loans on him. There was a moment of iced glare – then the dark eyes sparked into warmth as Bruce smiled.

‘Aye. To get into trouble as a wayward young son, which will let me get out of it again as easily. More freedom than Sir William here, who has all the weight of the Order bearing down on him – and the Order takes instruction from England.’

‘Clifton is a fair Chaplain in Ballantrodoch,’ the Auld Templar growled. ‘He gave me leave to return to Roslin until my bairns are released, though the new Scottish Master, John of Sawtrey, will follow what the English Master De Jay tells him. The pair are Englishmen first and Templars second. It was De Jay put my boy in the Tower.’

‘I follow that well enough,’ Bruce said and put one hand on the old Templar’s shoulder. He knew, as did everyone in the room, that those held in the Tower seldom came out alive.

‘If God is on the side of the right, then you will be rewarded . . . how is it you say it? At the hinter end?’

‘Not bad, Lord,’ Sir William answered. ‘We’ll mak’ a Scot of you yet.’

For a moment, the air thickened and Bruce went still and quiet.

‘I am a Scot, Sir William,’ he said eventually, his voice thin.

The moment perched there like a crow in a tree – but this was Sir William, who had taught Bruce to fight from the moment his wee hand could properly close round a hilt, and Bruce knew the old man would not be cowed by a scowling youth, earl or not.

He had sympathy for the Auld Templar. The Order was adrift since the loss of the Holy Land and, though it owed allegiance only to the Pope, Sir Brian de Jay was a tulchan, at the beck of King Edward.

Eventually, Bruce eased a little and smiled into the blank, fearless face.

‘Anyway – tomorrow we hunt and find out if we are hunted in turn,’ he said.

‘Aye, there’s smart for ye,’ Sim burst out admiringly. ‘Och, ye kin strop yer wits sharper listenin’ to yer lordship and no mistake. There’s a kinch in the rope of it, all the same. Yon Buchan might try and salt yer broth – a hunt is a fine place for it.’

‘What did he say – a kinch? Rope?’ demanded Bruce.

‘He congratulates you on your dagger-like mind, lord,’ Kirkpatrick translated sarcastically into French, ‘but declares a snag. Buchan may try and spoil matters – salt your broth.’

Bruce ignored Kirkpatrick’s tone and Hal saw that the man, more than servant, less than equal, was permitted such liberties. A dark, close-hugged man of ages with himself, this Roger Kirkpatrick was a cousin of the young Bruce and a landless knight from Closeburn, where his namesake was lord. This one had nothing at all and was tied to the fortunes of the Carrick earl as an ox to the plough. And as ugly, Hal noted, a dark, brooding hood of a man whose eyes were never still.

‘Salt my broth,’ Bruce repeated and laughed, adding in English, ‘Aye, Buchan could arrange that at a hunt – a sprinkle of arrow, a shake of wee latchbow bolts, carelessly placed. Which is why I would have a wee parcel of your riders, Hal of Herdmanston.’

‘You have a wheen of yer own,’ Hal pointed out and Bruce smiled, sharp-faced as a weasel.

‘I do. Annandale men, who belong to my father and will not follow me entire. My own Carrick men – good footmen, a handful of archers and some loyal men-at-arms. None with the skills your rogues have and, more importantly, all recognisable as my own. I want the Comyn made uneasy as to who is who – especially Buchan’s man, the one called Malise.’

‘Him with the face like a weasel,’ Kirkpatrick said.

‘Malise,’ Sir William answered. ‘Bellejambe. Brother of Farquhar, the one English Edward made archdeacon at Caithness this year.’

‘An ill-favoured swine,’ Kirkpatrick said from a face like a mummer’s mask, a moment that almost made Hal burst with loud laughing; wisely, he bit his lip on it, his thoughts reeling.

‘Slayings in secret,’ he said aloud, while he was thinking, suddenly, that he did not know whether his father would leap with Bruce or Balliol. It was possible he would hold to King John Balliol, the Toom Tabard – Empty Cote – as still the rightful king of Scots, which would put him in the Balliol and Comyn camp. It seemed – how he had managed it was a mystery all the same – Hal had landed in the Bruce one.

Sir William saw Hal’s stricken face. He liked the boy, this kinsman namesake for his shackled grandson, and had hopes for him. The thought of his grandson brought back a surge of anger against Sir Brian de Jay, who had been instrumental in making sure that his son had been sent to the Tower. He would have had grandson Henry in there, too, the Auld Templar thought, but was foiled – the man hates the Sientclers because they wield influence in the Order.

Thanks be to God, he offered, that grandson Henry is held in a decent English manor, waiting for the day Roslin pays for his release. In the winter that was his heart, he knew his son would never return alive from the Tower.

Yet that was not the greatest weight on his soul. That concerned the Order and how – Christ forbid it – De Jay might bring it to the service of Longshanks. The day Poor Knights marched against fellow Christians was the day they were ruined; the thought made him shake his snowed head.

‘War is a sore matter at best,’ he said, to no-one in particular. ‘War atween folk of the same kingdom is worst.’

Bruce stirred a little from looking at the violet tunic, then nodded to Kirkpatrick, who sighed blackly and handed it over. Linen fit for trailing the weeng, Hal thought savagely. I have lashed myself to a man who thinks with his loins.

The day Buchan and Bruce had come to Douglas, he recalled, had been a feast dedicated to Saint Dympna.

Patron saint of the mad.

Chapter Two

Douglas Castle, later that day

Vigil of St Brendan the Voyager, May 1297

They waited for the Lady, knights, servants, hounds, huntsmen and all, milling madly as they circled horses already excited. The dogs strained at the leashes and leaped and turned, so that the hound-boys, cursing, had to untangle the leashes to load them in their wooden cages on the carts.

Gib had the two great deerhounds like statues on either side of him and turned to sneer at Dog Boy. The Berner had given the stranger’s dogs into Gib’s care because Dog Boy was less than nothing and now Gib thought himself above all the sweat and confusion and that the two great hounds leashed in either fist were stone-patient because of him. Dog Boy knew better, knew that it was the presence of the big Tod’s Wattie nearby.

Hal frowned, because the deerhounds, if they had chosen, could leap into the mad affray and four men would not hold them if their blood was up, never mind a tall, scowling boy with the beginning of muscle and a round face fringed with sandy hair. With his lashes and brows and snub nose, it all contrived to make him look like an annoyed piglet; he was not the one with the charm over the deerhounds and Hal knew the Berner had arranged this deliberately, as a snub, or to huff and puff up his authority.

The one with the hound-skill – Hal sought him out, caught his breath at the stillness, the stitched fury in the hem of his lips, the violet dark under his hooded eyes and the dags of black hair. Darker than Johnnie, he thought . . . as he had thought last night, the lad had the colouring and look of Jamie and might well be one of The Hardy’s byblows, handed in to the French hound-master of Douglas for keeping. Hal switched his gaze to fasten on Berner Philippe, standing on the fringes of the maelstrom and directing his underlings with short barks of French.

The weight of those eyes brought the Berner’s head up and he found the grey stare of the Lothian man, blanched, flushed and looked away, feeling anger and . . . yes, fear. He knew this Sientcler had been given the Dog Boy by the Lady, passed to him without so much as a ‘by your leave, Berner’, and that had rankled.

When told – told, by God’s Wounds – that the Dog Boy would look after the deerhounds he had decided, obstinately, to hand them to Gib. It was, he knew, no more than a cocked leg marking his territory – all dogs in Douglas were his responsibility, no matter if they were visitors or not – and he did not like being dictated to by some minor lordling of the Sientclers, who all thought themselves far too fine for ordinary folk.

He liked less the feel of that skewering stare on him, all the same, busied himself with leashes and orders, all the time feeling the grey eyes on him, like an itch he could not scratch.

Buchan sat Bradacus expertly and fumed with a false smile. The hunt had been the Bruce’s idea at table the night before and he had spent all night twisting the sense of it to try to the Bruce advantage in it. Short of a plot to kill him from a covert, he had failed to unravel it, but since he’d had nothing else to occupy him the time wasted had scarcely mattered. The bitterness of that welled up with last night’s brawn in mustard, a nauseous gas that tasted as vile as his marriage to the MacDuff bitch.

It had seemed an advantageous match, to him and the MacDuff of Fife. Yet Isabel’s own kin, bywords for greed and viciousness, had slain her father, which was no great incentive for joing the family. Even at the handseling of it, Red John Comyn of Badenoch had tilted his head to one side and smeared a twisted grin on his face.

‘I hope the lands are worth it, cousin,’ he had said savagely to Buchan, ‘for ye’ll be sleeping with a she-wolf to own them.’

Buchan shivered at the claw-nailed memory of the marriage night, when he had broken into Isabel MacDuff. He had done it since – every time she was returned from her wanderings – and it was now part of the bit, as much as lock, key and forbiddings to make her a dutiful wife, fit for the title of Countess of Buchan. That and the getting of an heir, which she had so far failed to do; Buchan was still not sure whether she used wile to prevent it or was barren.

Now here she was, supposedly ridden to Douglas on an innocent visit and using Bradacus’ stablemate, Balius, to do it. Christ’s Wounds, it was bad enough that she was unchaperoned – though she claimed such from the Douglas woman – but without so much as a servant and riding a prime Andalusian warhorse in a country lurking with brigands was beyond apology.

She could be dead and the horse a rickle of chewed bones . . . he did not know whether he desired the first more than he feared the second, but here she was, snugged up in a tower, refusing him his rights while he languished in his striped panoply in the outer ward, too conscious of his dignity to make a fuss over it.

That dropped the measure of her closer to the nunnery he was considering. He was wondering, too, if she and Bruce . . . He shook that thought away. He did not think she would dare – but he had set Malise to scout it out.

Now he sat and fretted, waiting for her to appear so they could begin this accursed hunt, though if matters went as well as the plans laid, the Gordian knot of the Bruces would be cut. Preferably, he thought moodily, before Bruce’s secret blade.

Which, of course, was why he and his men chosen for this hunt were armed as if for war, in maille and blazoned surcoats; he noted that the Bruce was resplendant in chevroned jupon, bareheaded and smiling at the warbling attempts of young Jamie Douglas to sing and play while controlling a restive mount. Yet he had men with him, unmarked by Carrick livery so that no-one could be sure who they belonged to.

He looked them over; well armed and mounted on decent garrons. They looked like they had bitten hard on life and broken no teeth – none more so than their leader, the young lord from Herdmanston.

Hal felt the eyes on him and turned to where the Earl sat on his great, sweating destrier, swathed in a black, marten-trimmed cloak and wearing maille under it. The face framed by a quilted arming cap was broad, had been handsome before the fat had colonised extra chins, was clean-shaven and sweating pink as a baby’s backside.

The Earl of Buchan was a dozen years older than Bruce, but what advantage in strength that gave the younger man was offset, Hal thought, by the cunning concealed in those hooded Comyn eyes.

Buchan acknowledged the Herdmanston’s polite neck-bow with one of his own. Bradacus pawed grass and snorted, making Buchan pat him idly, feeling the sweat-slick of his neck even through the leather glove.

He should have begged a palfrey instead of riding a destrier to a hunt, he thought moodily, but could not bring himself to beg for anything from the Douglases or Bruces. Now a good 25 merks of prime warhorse was foundering – not to mention the one his wife had appropriated, and he was not sure whether he fretted more for her taking a warhorse on a jaunt or for her clear, rolling-eyed flirting with Bruce at table the night before.

Brawn in mustard and a casserole of wheat berries, pigeon, mushrooms, carrots, onions and leaves – violet leaves and lilac flowers, the Lady Douglas had said proudly. With rose petals. Buchan could still feel the pressure of it in his bowels and had been farting as badly as the warhorse was sweating.

It had been a strange meal, to say the least. Old Brother Benedictus had graced the provender and that was the last he said before he fell asleep with his head in his rose petals and gravy. The high table – himself, Bruce, the ladies, wee Jamie Douglas, the Inchmartins, Davey Siward and others -had been stiffly cautious.

All save Isabel, that is. The lesser lights had yapped among themselves, friendly enough save for those close to the salt, when the glowering and scowling began at who had been placed above and below it.

Conversation had been muted, shadowed by the distant cloud that was King Edward – even in France, Buchan thought moodily, Longshanks casts a long shadow. He had put Bruce right on a few points and been pleased about it, while giving nothing away to clumsy probings about his intentions regarding the rebelling Moray.

‘Exitus acta probat,’ he had answered thickly, choking on Isabel’s smiles and soft conversation with the Lady, talking right across him and ignoring him calculatedly.

‘I hope the result does validate the deeds,’ a cold-eyed Bruce had answered in French, ‘but that’s a wonderful wide and double-edged blade you wield there.’

Hal would have been surprised to find that he and Buchan shared the same thoughts, though his had been prompted by the sight of the Dog Boy, whose life had been wrenched apart and reformed at last night’s feast as casually as tossing a bone to a dog.

‘Your hounds are settled?’ Eleanor Douglas had called out to Hal, who had been placed – to his astonishment – at the top of the lesser trestle and within touching distance of the high table. He thought she was trying to unlatch the tension round her and went willing with it. Then he found she only added to it.

‘Yon lad is a soothe to them, mistress,’ he had replied, one ear bent to the grim, clipped exchanges between Buchan and Bruce.

‘It pleases me, then, to give you the boy,’ the Lady said, smiling. Hal saw the sudden, stricken look from Jamie, spoon halfway to his mouth, and realised that the Lady knew it, too.

‘Jamie will have me a wicked stepma from the stories,’ she went on, not looking at her stepson, ‘but he spends ower much time with that low-born chiel, so it is time they were parted and he learns the way of his station.’

Hal had felt the cleft of the stick and, with it, a spring of savage realisation – the hound-boy is a byblow of The Hardy, he thought to himself, and the wummin finds every chance to have revenge on wayward husband and her increasingly fretting stepson. Gutterbluid was one and now I am another – a dangerous game, mistress. He glanced at Jamie, seeing the stiff line of the boy, the cliff he made of his face.

‘I shall take careful care of the laddie,’ he had said, pointedly looking at Jamie and not her, ‘for if he quietens those imps of mine, he is worth his weight.’

He realised the worth of his gift only later and, staring at the scrawny lad, marvelled at the calm he brought to those great beasts; the Berner’s mean spirit came back to make Hal frown harder and he suddenly became aware that he was doing it while glaring at the Earl of Buchan.