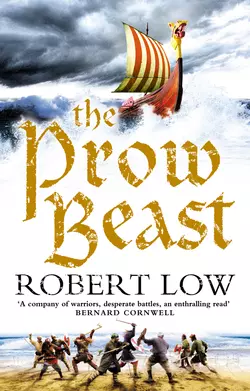

The Prow Beast

Robert Low

The epic and action packed fourth novel in the Oathsworn series, charting the adventures of Orm and his band of Viking brothers.The Oathsworn have become feared and respected throughout the Viking world. Their name goes before them and men cower in their presence. But fame comes at a price…While the Oathsworn revel in their new-found fame, Sterki, an old enemy with revenge in his heart, attacks their homestead - the Fjord Elk is sunk, old oarmates die and the Oathsworn are forced to flee into the mountains.Unused to losing, the Oathsworn retreat to lick their wounds. They have been entrusted with the care of Queen Sigrith, pregnant and soon to bear the heir to the crown of Sweden, and though the urge for revenge is strong, Orm's first duty is to protect the queen. And Orm soon realises that revenge is not the only thing on Sterki's mind; he has joined forces with Styrbjorn, nephew of King Eirik and next in line to the throne if he can only get rid of the current heir.As the Oathsworn fight to defend themselves and their newfound celebrity and fortune, they're soon to realise that fame isn't all it's cracked up to be…

The Prow Beast

Robert Low

HarperCollinsPublishers

To my daughter Monique – all the treasure this father needs

The prow-beast, hostile monster of the mast

With his strength hews out a file

On ocean’s even path, showing no mercy

Egil Skallagrimsson

Table of Contents

Cover Page (#u903e17b8-c5f8-5e9e-a27c-a61a0c6d6920)

Title Page (#u0066ae89-73e0-56f0-a86f-3495d1b66375)

Dedication (#uc19e60f5-3bc8-5937-a0af-7159addcea59)

Epigraph (#uac1385bc-ea6c-5a09-a7a8-0042dbc83bf5)

Maps (#ua2d6c1fa-3487-5414-ac2b-b6525e474d42)

AUSTRGOTALAND, 975AD (#u4423832c-9008-50b4-a89c-48be3023bc9a)

ONE (#ued0deed7-b023-599b-9bf4-fe1de3e93365)

TWO (#ud2285161-fbd4-5d80-a114-a1a53063c15f)

THREE (#u66802792-8365-59bc-bdcd-6da608c4b604)

FOUR (#u4ce1f011-1bd7-5988-8743-9fc3fd4e8de1)

FIVE (#u57d363ed-c797-566d-a443-0a6916ad5fd7)

SIX (#litres_trial_promo)

SEVEN (#litres_trial_promo)

EIGHT (#litres_trial_promo)

NINE (#litres_trial_promo)

TEN (#litres_trial_promo)

ELEVEN (#litres_trial_promo)

TWELVE (#litres_trial_promo)

THIRTEEN (#litres_trial_promo)

FOURTEEN (#litres_trial_promo)

FIFTEEN (#litres_trial_promo)

SIXTEEN (#litres_trial_promo)

SEVENTEEN (#litres_trial_promo)

EIGHTEEN (#litres_trial_promo)

NINETEEN (#litres_trial_promo)

HESTRENG, high summer (#litres_trial_promo)

HISTORICAL NOTE (#litres_trial_promo)

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS (#litres_trial_promo)

Also by Robert Low (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Maps (#ulink_66e94dff-fbf0-5e37-bcc3-10eddf99f5eb)

AUSTRGOTALAND, 975AD (#ulink_5973419c-4924-5387-8228-9fc6bcda48a7)

The sun stayed veiled behind lead clouds streaked with silver. The rain hissed and the sea heaved, black and sluggish as a walrus on a rock, while a wind dragged a fine smoke of spray into my eyes.

‘Not storm enough,’ Hauk Fast-Sailor declared and he had the right of it, for sure. There was not enough of a storm to stop our enemies from coming up the fjord with the wind in their favour and that great, green-bordered sail swelled out. On a ship with a snarling serpent prow that sail looked like dragon wings and gave the ship its name.

The oars on the Fjord Elk were dipped, but moving only to keep the prow beast snarling into the wind that drove the enemy down on us; there was no point in tiring ourselves – we were crew-light, after all – while the enemy climbed into their battle gear. When we saw their sail go down would be the time for worry, the time they were ready for war.

Instead, men kept their hands busy tightening straps and checking edges, binding back their hair as it whipped in the wind. All of Jarl Brand’s lent-men from Black Eagle were here, save six with Ref and Bjaelfi who were herding women and weans and thralls away from Hestreng hall and up to the valley, with as much food and spare sail for tentage as they could carry. Away from the wrath of Randr Sterki and the snarlers on Dragon Wings.

I hoped Randr Sterki would content himself with looting and burning Hestreng, would not head inland too far. I had left him wethers and cooped hens and pigs to steal, as well as a hall and the buildings to burn – and if it was the Oathsworn he wanted…well, here we were, waiting for him at sea.

Still, I knew what drove Randr to this attack and could not blame him for it. I had the spear in my throat and the melted bowels that always came with the prospect of facing men who wanted to cleave sharp bars of metal through me but, for once, did not wish to be elsewhere. This was where I had to be, protecting the backs of mine and all the other fledglings teetering on flight’s edge, from the revenge of raiding men.

Men like us.

Gizur, swinging down from stay to stay through the ranks of men, looked like a mad little monkey I had seen once in Serkland, his weather-lined face such a perfect replica that I smiled. He was surprised at that smile, considering what we faced, then grinned back.

‘We should ship oars, Jarl Orm, before they get splintered.’

I nodded; when the ships struck, the oars on that side would be a disaster to us if we left them out. There was a flurry and clatter as the oars came in and were stacked lengthways; men cursed as shafts dunted them and now I saw the great snarling prow of Dragon Wings clearly, heard the faint shrieks and roars, saw the weapon-waving.

I was watching them flake the sail down to the yard when two of Jarl Brand’s lent-men shoved through our throng, almost to the Fjord Elk’s prow, nocking arrows as they went, stepping over bundled oars and shoving folk aside. They shot; distant screams made our own men roar approval – then curse as an answering flight zipped and shunked into the woodwork. One of the bowmen, Kalf Sygni, spun half round and clutched his forearm where a shaft was through, side to side.

‘Missed that coming,’ bellowed Finn, hefting his shield as he moved to the prow, clashing ring-iron shoulders with Nes-Bjorn, who was headed the same way; they glared at each other.

‘I am Jarl Brand’s prow man on the Black Eagle,’ Nes-Bjorn growled.

‘You are not on the Black Eagle,’ Finn pointed out and, reluctantly, the big man gave way, letting Finn take his place. Across on Dragon Wings his counterpart, hero-warrior of his boat, stepped up, mailed, helmeted and carrying a shield, but nothing better than a ship-wood axe.

They had the sail down and the oars shipped, leaving Dragon Wings with enough momentum to crash on us, rocking the Elk sideways to the waterline, staggering men who had been unprepared for it. Randr’s crew howled and axes clattered over our side, causing men to duck and raise shields – the axe-owners hauled hard at the ropes ringed to the shafts, pulling the hooked heads tight to the inside of the Elk with their iron beards, clinching us close as lovers.

A man screamed as his leg went with such a pull, trapping him like a snared fox against the side while he beat and tugged. Holger, I remembered dully as he screamed his throat out in agony. His name was Holger.

An arrow skittered off the mast and whipped past my head; I wore no ring-coat, for I was not so sure I could wriggle out of it in time if I fell overboard. Botolf, who stood on my right, heard me curse and grinned.

‘Now you know what it feels like,’ he yelled and I laughed into his mad delight, for it was a long-standing joke that Botolf had never found a ring-coat big enough to fit him. Then he threw back his head and roared out his name; Randr Sterki’s men shrieked and howled; the sides of the boats clashed and men flung themselves forward while the locked ships groaned and rocked.

The worst thing about battle, after a few bloodings drive away the first fears of it, is that it is work. The stink and the horror, the belly-wrenching terror and savage hatred of it were all things I had grown used to – but the backbreaking labour of it was what always made me blench. It was like ploughing stony ground, where the stones rise up and try to hit you and the whole affair leaves you sick and tremble-legged with exhaustion. The one good part about being jarl was that you did not sink into the grind of it, at least not all at once – but you had to stand like a tree in a boiling flood and seem unconcerned.

I stood rock-still and guarded by Botolf’s shield, watching the Dragon Wings crew pile forward in a rush, dipping both ships almost into the water with their weight. They struggled and hacked and died on the thwart-edges, my picked men darting in to cut the ropes that bound us together, or shoot out the men on Dragon Wings whose task it was to haul us tight.

They were red-mouthed screamers, Randr Sterki’s crew, waving spears and axes, garbed in leather and some in no more than makeshift breastplates of knotted rope. They had helms of all kinds, none of them fine craftings, and waved blades as notched as a dog’s jaw – even Randr Sterki’s ring-mailed prow man wielded no better than an adze-axe. Yet they had the savagery of revenge in them and that made the arm strong and the edge sharp.

Randr stood and roared out unheard curses in the middle of his ship, in the middle of a group as unlike the men round them as sheep-droppings in snow. They made my knees turn to water, those men whose eyes stared and saw nothing, who wore only thick, hairy hides over their breeks, who champed flecks of foam onto the thicket of their beards and hefted weapons with an easy skill and arms blood-marked with strength runes. Some of them, I noted, had swords, well-worn and well-earned.

‘Bearcoats!’ yelled Botolf in my ear. ‘He has bearcoats, Orm…’

Even as he spoke I saw them, all twelve of them, stir like a wolf pack scenting a kill. Bearcoats – berserker – had been no part of Randr Sterki’s crew before. Where had he got them from? My mouth went dry; I saw them snarling and howling, slamming into those of their own side who did not see them in time to get out of the way.

The first of them, tow-haired, tangle-bearded, reached the side and howled out to the sky, then hurled himself over on my men before the cords of his neck had slackened; they hacked at him with the desperate fury of those too trapped to run. The rest of the pack began to follow and Randr Sterki urged them on with bellows from the middle of his ship, his face red and ugly with rage and battle.

‘We shall have to kill Pig-Face,’ panted Nes-Bjorn, suddenly on my other side, pointing to Randr. If he was cursing at having been left behind by Jarl Brand to serve with us on this seemingly bad-wyrded day, his cliff of a face did not show it.

‘First stop the bearcoats,’ I pointed out, as calmly as I could while watching Tow-Hair carve his way towards me, trailing blood and screams; Botolf hefted his shield and byrnie-biter spear and braced himself on his one good leg. I raised my own sword a little, as if only resting it lightly on one shoulder, while my throat was full of my heart at the sight of a berserker slashing a path straight to me.

‘Ach,’ said Nes-Bjorn with a dismissive wave of his bearded axe. ‘We have our own man for that.’

At which point came a growling grunt from behind me, so like the coughing charge-roar of a boar that I half-spun in alarm. Then a half-naked figure with skin-marks of power and an axe in either hand launched straight over the heads of my own men, scattering them as he clattered into the howling bearcoat. Tow-Hair went down in a bloody eyeblink and the axes flailed on in Stygg Dusi’s fists, his carefully applied skin-marks streaked with blood, as he hurled himself in a bellowing whirl of arms and legs and axes over the side and into the crowded Dragon Wings. Men scattered before him.

‘Stygg Dusi,’ Nes-Bjorn pointed out and split a feral grin as the man by-named Shy Calm howled and chopped and died hard in the middle of the enemy ship.

‘There are twelve of them,’ I offered and Nes-Bjorn scowled.

‘Eleven now – no, ten, for Stygg has done well. Have you a point to make, Jarl Orm of the Oathsworn, or are you just after showing your skill at tallying?’

Then he elbowed men aside to reach the prow, where Finn, gasping and exhausted, had been forced to step back, ropey strings drooling from his mouth. The Dragon Wings prow man was nowhere to be seen.

I listened and watched as Stygg Dusi served out the last seconds of what the Norns had woven for him from the moment he slithered wetly into the world. Everything he had done had led to this place, this moment, and I raised my sword to the life he honoured us with, almost envied him in the certainty of his place in Valholl. Not yet, but soon, I was thinking, the old message we gave to all the dying to take with them to those gone before. Very soon now, it seemed.

The last rope was cut; Kalf Sygni, with the arrow still through his forearm, managed to shoot the last rope-hauler and the ships drifted apart from the stern, so that the prow beasts bobbed and snarled, almost seeming to strike out at each other. Men from both crews, trapped on the wrong boat, tried to fight their way to a thwart edge and leap for it.

Everything after that became a blur to me. I remember shoulder-charging a man, sending him flying into the water and it was only when he floundered there that I saw he wore a bearcoat. Finn loomed up, shook slaver and blood from his face, then launched back into the mad struggle, roaring curses and insults.

Hauk Fast-Sailor went down under the frenzied, raving chops of a wet-mouthed trio of bearcoats; Onund Hnufa went over the side, blood streaming from a cut on his head, and a man bound in knotted rope came at me, so that I had to kill him. By the time I looked, Onund had gone and I did not know if he had surfaced or not.

Something small and dark flew at the prow and Nes-Bjorn batted it contemptuously to one side. Flame engulfed him. Just like that. One minute he was roaring invites for someone to face him, the next minute he was enveloped in flame, a pillar of fire staggering about the prow. He fell back and men shrieked; one scrambled away screaming and batting at the flames on his leg, but that only caused his hands to flare. Another flung away a flaming shield, which hit the water and sank – but the water continued to burn in a circle.

‘Magic!’ yelled a voice, but it was no rune-curse, this. I had seen it before and the second little pot smacked into the Elk’s prow and burst into flames exactly as Roman Fire was supposed to. I watched the flames leap up the proud horns of Botolf’s carving, saw ruin in them even as the frantic crew of Dragon Wings saw those same flames leap to their own ship. Then Botolf yelled out that there was a second ship.

A second ship. Roman Fire. Bearcoats. These had been no part of Randr Sterki before now. I blinked and stared, my thoughts wheeling like the embers of my burning ship while men struggled and slipped and died, raving curses.

‘Orm – on your steerboard…’

I half-turned into a wet-red maw, where spittle skeined like spume off a wave. He had a greasy tangle of wild hair and eyes as mad as a kennel of frothing dogs, while the axe in his hand seemed as big as a wagon tree. I swung and missed, felt my sword bite into the wood of the mast, where it stuck.

I got my shield in the way a little, so that his axe splintered it and tore it sideways, out of my finger-short grasp. His whole body hit me then and there was a moment when I smelled the woodsmoke and grease stink of his pelt, the rankness of his sweat. My hand was wrenched from the hilt of my trapped sword.

Then there was only the whirl of silver sky and dark water and the great, cold plunge, like a hot nail in the quench.

ONE (#ulink_14e8ec61-f457-5ff9-95cd-6c88c75a707d)

Six weeks before…

The year cracked like a bad cauldron, just as winter unfastened its jaws a little and the cold ebbed to drip and yellow grass. Those from further south would say it was March and spring, but what did they know? It was still winter to us, who counted the seasons sensibly.

In the northlands we also know what causes the ground to move: it is the pain-writhing of Loki, when Loki’s wife has to empty her bowl, leaving her bound husband in agony, his face ravaged by the dripping poison of the serpent for the time it takes her to return and catch the venom again. The gods of Asgard gave dark Loki a hard punishment for his meddlings.

His writhings that year folded the cloak of the earth to new shapes with a grinding of stones, and great scarred openings, one of which swallowed an entire field close to us, kine and all.

A sign from the Aesir, Finn said moodily, echoing what others thought – that we should be back on the whale road and not huddled on land trying to be farmers. It was hard to ignore his constant low rumbling on the matter, harder still to put my head down and shoulder into the loud unspoken stares of the rest of them, day after day.

Odin had promised us fame and fortune and, of course, it was cursed, for he had not warned us to beware of what we sought so fiercely. Now that we had it, there was no joy in it for raiding men – what point raiding, as Red Njal grumbled, if you have silver and women enough? Nor was there any joy in trying to forsake the prow beast and cleave to the land, digging it up like worms, as Hlenni pointed out.

I heard them and their talk of the crushing wyrd of Odin. Others, still claiming to be Oathsworn, had wandered off into the world, with promises to be back at my side if the need arose, the old Oath binding them – We swear to be brothers to each other, bone, blood and steel, on Gungnir, Odin’s spear, we swear, may he curse us to the Nine Realms and beyond if we break this faith, one to another.

I accepted their promises with a nod and a clasping of hands, to keep the Oath alive and them from harm, though I did not expect to see any of them again. Those who remained struggled with the shackles that kept them from following the prow beast. They plodded grimly through winters in the hope that better weather might bring a new spark to send them coldwards and stormwards. It never seemed to flare into a fire of any fierceness, all the same.

The only ones who no longer moaned and grumbled were Botolf and Short Eldgrim, the first because he was no good on a raiding ship with one timber leg and, besides, had Ingrid and a daughter he cared more about; the second had no clear idea half the time of where he was, the inside of his head knocked out of him in a fight years before.

Finn had bairned Thordis in the fever that followed our return, silver-rich and fame-rich, and now she cradled their son, Hroald, in a sling of her looped apron. Finn looked at the boy every day with a mix of pride and misery, the one for what every father felt, the other for the forging of another link in a chain that chafed, for Thordis hourly expected a marriage offer.

On the other hand, when I looked across at Thorgunna and she let me know with her eyes that her own carrying was fine, there were no words, no mead of poetry that described how I felt at the news. It was a joy doubled, for she had lost a bairn before this and to find that it had not broken Thorgunna as a mother was worth all the silver Odin had handed us.

Yet the dull haar of disappointed men hung over Hestreng, so that the arrival of young Crowbone in a fine ship brought heads up, sniffing eagerly at his fire and arrogance like panting dogs on a bitch’s arse.

Crowbone. Olaf Tryggvasson, true Prince of Norway and a boy of twelve whose fair fame went before him like a torch and was so tied in with my own that swords and axes were lowered, since no-one could believe Crowbone had come to raid and pillage his friend, Orm of Hestreng.

He sat in my hall rubbing sheep fat into his boots, the price you pay for being splendidly careless and leaping off the prow of a fine ship into the salt-rotting shallows.

I had not seen him in three years and was astounded. I had left a nine-year-old boy and now found a twelve-year-old man. He was sharp-chinned and yellow-haired, his odd-coloured eyes – one brown as a nut, the other blue-green as sea ice – were bland as always and his hair was long enough to whip in the wind, though two brow braids swung, weighted with fat silver rings woven into the ends. I was betting sure that the one thing he wanted, above all else, was to grow hair on his chin.

He wore red and blue, with a heavy silver band on each arm and another, the dragon-ended jarl torc of a chief, at his neck. He had a sword, cunningly made for his size, snugged up in a sheath worked with snake patterns and topped and tailed with bronze. He had come a long way in the three years since I had freed him from where he had been chained by the neck to the privy of a raider called Klerkon.

I said that to him, too, and he smiled a quiet smile, then answered that he had not come as far as me, since he had started as a prince and I had come to being jarl of the legendary Oathsworn from being a gawk-eyed stripling of no account. Which showed what he had learned in oiled manners and gold-browed words at the court of Vladmir.

‘A fine ship,’ I added as his growlers, all ringmail and swagger, filed in to argue places by the hearthfire. He swelled with pride.

‘Short Serpent is the name,’ he declared. ‘Thirty oars a side and room for many more men besides.’

‘Short Serpent?’ I asked and he looked at me, serious as a wrecking.

‘One day I will have one bigger than this,’ he replied. ‘That one I will call Long Serpent and it will be the finest raiding ship afloat.’

‘Is Hestreng ripe for a strandhogg, then?’ I asked dryly, for already the fame of this boy was known in halls the length of the Baltic, where he had been hit-and-run raiding – the strandhogg – all year.

Crowbone only grinned and shook his head so that the rings tinkled. Then I saw they were not rings at all, but coins with holes punched through them and Crowbone’s grin grew wider when he saw I had spotted that. He fished in his pouch and brought out another, a whole one, which he spun at me until I made it vanish in my fist.

‘I took it and its brothers and cousins from traders bound for Kiev,’ Crowbone said, still grinning. ‘We will choke the life from Jaropolk before we are done.’

I looked at it – a glance was all it took, for minted silver was rare enough for me to know all the coins that whirled like bright foam along the Baltic shores. It was Roman, a new-minted one they call miliaresion and silver-light compared with other, older cousins that spilled out of Constantinople, which we called Miklagard, the Great City. The ones Crowbone had braided into the ends of his hair were gold nomisma, seventy-two to a Roman pound and, I saw, with the head of Nicepheros on them, which made them recent – and one-quarter light.

I said this as I spun it back to him and he grinned, suitably admiring my skill. He had skills of his own when it came to coinage, all the same – backed by the ships and men of Vladimir, Prince of the Rus in Novgorod, he had ravaged up and down the Baltic to further the cause of his friend against Vladimir’s brothers, Jaropolk and Oleg. They were not quite at open war, those three Kievan brothers, but it was a matter of time only and the trade routes in their lands were ravaged and broken as a result.

That and the lack of silver from the east that made Crowbone’s coin rare – and light – also made any trade trip there worthless unless you went all the way down the rivers and cataracts to the Great City. I said as much while Thorgunna and the thrall women served platters and ale and Crowbone grinned cheerfully, uncaring little wolf cub that he was.

A shadow appeared at his elbow and I turned to the mailed and helmeted figure who owned it; he stared back at me from under his Rus horse-plume and face-mail, iron-grim and stiff as old rock.

‘Alyosha Buslaev,’ declared little Crowbone with a grin. ‘My prow man.’

Vladimir’s man more like, I was thinking, as this Alyosha closed in on Crowbone like a protecting hound, sent by the fifteen-year-old Prince of Novgorod to both guard and watch his little brother-in-arms. They were snarling little cubs, the Princes Vladimir and Olaf Crowbone, and thinking on them only made me feel old.

The hall was crowded that night as we feasted young Crowbone and his crew with roast horse, pork, ale and calls to the Aesir, for Hestreng was still free of the Christ and mine was still the un-partitioned hall of a raiding jarl – despite my best efforts to change that. Still, as I told Crowbone, the White Christ was everywhere, so that the horse trade was dying – those made Christian did not fight horses in the old way, nor eat the meat.

‘Go raiding,’ he replied, with the air of someone who thought I was daft for not having considered it. Then he grinned. ‘I forgot – you do not need to follow the prow beast, with all the silver you have buried away under moonlight.’

I did not answer that; young Crowbone had developed a hunger for silver, ever since he had worked out that that was where ships and men came from. He needed ships and men to make himself king in Norway and I did not want him snuffling after any moonlit burials of mine – he had had his share of Atil’s silver. That hoard had been hard come by and I was still not sure that it was not cursed.

I offered horn-toasts to the memory of dead Sigurd, Crowbone’s silver-nosed uncle, who had been the nearest to a father the boy had had and who had been Vladimir’s druzhina commander. Crowbone joined in, perched on the high-backed guest bench beside me, his legs too short to rest his feet like a grown man on the tall hearthstones that kept drunk and child from tumbling in the pitfire.

His men, too, appreciated the Sigurd toasts and roared it out. They were horse-eating men of Thor and Frey, big men, calloused and muscled like bull walruses from sword work and rowing, with big beards and loud voices, spilling ale down their chests and boasting. I saw Finn’s nostrils flare, drinking in the salt-sea reek of them, the taste of war and wave that flowed from them like heat.

Some of them wore silk tunics and baggier breeks than others, carried curved swords rather than straight, but that was just Gardariki fashion and, apart from Alyosha, they were not the half-breed Slavs who call themselves Rus – rowers. These were all true Swedes, young oar-wolves who had crewed with Crowbone up and down the Baltic and would follow the boy into Hel’s hall itself if he went – and Alyosha was at his side to make the sensible decisions.

Crowbone saw me look them over and was pleased at what he saw in my face.

‘Aye, they are hard men, right enough,’ he chuckled and I shrugged as diffidently as I could, waiting for him to tell me why he and his hard men were here. All that had gone before – politeness and feasting and smiles – had been leading to this place.

‘It is good of you to remember my uncle,’ he said after a time of working at his boots. The hall rang with noise and the smoke-sweat fug was thicker than the bench planks. Small bones flew; roars and laughter went up when one hit a target.

He paused for effect and stroked his ringed braids, wanting moustaches so badly I almost laughed.

‘He is the reason I am here,’ he said, raising his voice to be heard. It piped, still, like a boy’s, but I did not smile; I had long since learned that Crowbone was not the boy he seemed.

When I said nothing, he waved an impatient little hand.

‘Randr Sterki sailed this way.’

I sat back at that news and the memories came welling up like reek in a blocked privy. Randr the Strong had been the right-hand of Klerkon and had taken over most of that one’s crew after Klerkon died; he had sailed their ship, Dragon Wings, to an island off Aldeijuborg.

Klerkon. There was a harsh memory right enough. He had raided us and lived only long enough to be sorry for it, for we had wolfed down on his winter-camp on Svartey, the Black Island, finding only his thralls and the wives and weans of his crew – and Crowbone, chained to the privy.

Well, things were done on Svartey that were usual enough for red-war raids, but men too long leashed and then let loose, goaded on by a vengeful Crowbone, had guddled in blood and thrown bairns at walls. Later, Crowbone found and killed Klerkon – but that is another tale, for nights with a good fire against the saga chill of it.

Randr Sterki had a free raiding hand while matters were resolved with Prince Vladimir over the Klerkon killing, but when all that was done, Vladimir sent Sigurd Axebitten, Crowbone’s no-nose uncle and commander of his druzhina, to give Randr a hard dunt for his pains.

Except Sigurd had made a mess of it, or so I heard, and Crowbone had grimly followed after to find Randr Sterki and his men gone and his uncle nailed to an oak tree as a sacrifice to Perun. His famous silver nose was missing; folk said Randr wore it on a leather thong round his neck. Crowbone had been wolf-sniffing after his uncle’s killer since, with no success.

‘What trail did he leave, that brings you this way?’ I asked, for I knew the burn for revenge was fierce in him. I knew that fire well, for the same one scorched Randr Sterki for what we had done to his kin in Klerkon’s hall at Svartey; even for a time of red war, what we had done there made me uneasy.

Crowbone finished with his boots and put them on.

‘Birds told me,’ he answered finally and I did not doubt it; little Olaf Tryggvasson was known as Crowbone because he read the Norns’ weave through the actions of birds.

‘He will come here for three reasons,’ he went on, growing more shrill as he raised his voice over the noise in the hall. ‘You are known for your wealth and you are known for your fame.’

‘And the third?’

He merely looked at me and it was enough; the memory of Klerkon’s steading on Svartey, of fire and blood and madness, floated up in me like sick in a bucket.

There it was, the cursed memory, hung out like a flayed skin. Fame will always come back and hag-ride you to the grave; my own by-name, Bear Slayer, was proof of that, since I had not slain the white bear myself, though no-one alive knew that but me. Still, the saga of it – and all the others that boasted of what the Oathsworn were supposed to have done – constantly brought men looking to join us or challenge us.

Now came Randr Sterki, for his own special reasons. The Oathsworn’s fame made me easy to find and, with only a few fighting men, I was a better mark to take on than a boatload of hard Rus under the protection of the Prince of Novgorod.

‘Randr Sterki is not a name that brings warriors,’ Crowbone went on. ‘But yours is and any man who deals you a death blow steals your wealth, your women and your fame in that stroke.’

It was said in his loud and shrill boy’s voice – almost a shriek – and it was strange, looking back on it, that the hall noise should have ebbed away just then. Heads turned; silence fell like a cloak of ash.

‘I am not easily felled,’ I pointed out and did not have to raise my voice to be heard. Some chuckled; one drunk cheered. Red Njal added: ‘Even by bears,’ and got laughter for it.

Then the hall was washed with murmurs and subdued whispers; feasting flowed back to it, slow as pouring honey.

‘Did you come all this way to warn me?’ I asked as the noise grew again and he flushed, for I had worked out that he had not been so driven just for that.

‘I would have your Sea-Finn’s drum,’ he answered. ‘If it speaks of victory – will you join the hunt for Randr Sterki?’

Vuokko the Sea-Finn had come to us only months since, seeking the runemaster Klepp Spaki, who was chipping out the stone of our lives in the north valley. Vuokko came all the way from his Sami forests to learn the true secret of our runes from Klepp and no-one was more surprised than I when the runemaster agreed to it.

Of course, in return, Klepp had Vuokko teach him his seidr-magic, which was such that the little Sea-Finn was already well-known. Since seidr was a strange and unmanly thing, there were whispers of what the pair of them did all alone up in a hut in the valley – but muted ones, for Klepp was a runemaster and so a man of some note.

Vuokko, of course, was an outlander Sami sorcerer and not to be trusted at all, but it seemed folk were coming over the sea to hear the beat of his rune-marked drum and watch the three gold frogs on it dance, revealing Odin’s wisdom to those brave – or daft – enough to want to know it.

I saw Thorgunna, serving ale to Finn, Onund Hnufa and Red Njal, three heads close together and bobbing with argument and laughter. She smiled and the warmth of that scene, of my woman and my friends, washed me; then she gently touched her belly and moved on and the leap of that in my heart almost brought me to my feet.

‘Will you hunt down Randr, Sigurd’s bane, with me?’

The voice was thin with impatience, jerking me back from the warmth of wife and unborn. I turned to him and sighed, so that he saw it and frowned.

The truth was I had no belly for it. We had gained fame and wealth at a cost – too high, I often thought these days – and now the idea of sluicing sea and hard bread and stiff joints on a trip even across to Aldeijuborg made me wince. Even that was a hare-leap of joy compared to sailing off with this man-boy to hunt round the whole Baltic for the likes of Randr Sterki.

I said as much. I did not add that I thought Randr Sterki had a right to feel vengeful and that Crowbone had played a part in fuelling the fire on Svartey.

I heard the air hiss from him and there was petulance as much as disappointment in that, for young Crowbone did not like to be crossed.

‘There is fame and the taste of victory,’ he argued, pouting into my twist of a smile.

I already had fame, while victory, when all is said and done, tastes as blood-foul as failure – which was the other side of the spinning coin in this matter. He scowled at that, his eyes reflecting me to myself – what I saw there was old and done, but it was the view from a boy of twelve and almost made me chuckle. Then Crowbone found himself and smiled blandly; more signs of the princely things learned from Vladimir, I saw.

‘I will have the drum-frogs leap for me, all the same,’ he said and I nodded.

As if he had heard, Vuokko came into the hall, so silently that one of the younger thrall girls, too fondled by these new and muscled warriors to notice, gave a scream as the Sea-Finn appeared next to her.

Men laughed, though uneasily, for Vuokko had a face like a mid-winter mummer’s mask left too long in the rain, which the wind-guttered sconces did not treat kindly. The high cheekbones flared the light, making the shadows there darker still, while the eyes, slits of blackness, had no pupils that I could see and the skin of his face was soft and lined as an old walrus.

He grinned his pointed-toothed smile and sidled in, all fur and leather and bits of stolen Norse weave, hung about with feathers and bone both round his neck and wound into the straggles of his iron-grey hair.

In one hand was the drum of white reindeer skin marked with runes and signs only he knew, festooned with claws and little skulls and tufts of wool; on the surface, three frogs skittered, fastened to a ring that went round the whole circle of it. In his other hand was a tiny wooden hammer.

Men made warding signs and muttered darkly, but Crowbone smiled, for he knew the seidr, unmanly work of Freyja though that magic was, and a Sea-Finn’s drum held no terrors for a boy who saw into the Other by the actions of birds. I wondered if he still had some more of the strange stories he had chilled us all with last year.

‘This grandson of Yngling kings,’ I said pointedly to the Finn, ‘wants a message from your drum on an enterprise he has.’

The Sea-Finn grinned his bear-trap grin, as if he had known all along. He produced a carved runestick from his belt and then drew a large square in the hard, beaten earth of the floor – folk sidled away from him as he came near.

Then he marked off two points on all the sides and scraped lines to join them; now he had nine squares and folk shivered as if the fire had died. In the middle square, the square within a square, he folded into a cross-legged sit and cradled the drum like a child, crooning to it.

He rocked and chanted, a deep hoom in the back of his throat that raised hackles, for most knew he was calling on Lemminki, a Finnish sorcerer-god who could sing the sand into pearls for those brave enough to call on him. The square within a square was supposed to keep Vuokko safe – but folk darted uneasy looks at the flickering shadows and moved even further away from him.

Finally, he hit the drum – once only – a deep and resonating bell of sound coming from such a small thing; men winced and shifted and made Hammer signs and I saw Finn join his hands in the diamond-shape of the ingwaz warding rune as the gold frogs danced. No man cared for seidr magic, for it was a woman’s thing and to see a man do it set flesh creeping.

Vuokko peered for a long time, then raised his horror of a face to Crowbone. ‘You will be king,’ he said simply and there was a hiss as men let out their breath all at once together, for that had not been the enterprise I had meant.

Crowbone merely smiled the smile of a man who had had the answer he expected and fished in his purse, drawing out his pilfered coin. He flicked it casually in the air towards Vuokko, who never took his eyes from Crowbone’s face, ignoring the silver whirl of it.

I was astounded by the boy’s arrogance and his disregard – you did not treat the likes of Vuokko like some fawning street-seer, nor did you break the safety of his square within a square while he was in the Sitting-Out, half in and half out of the Other, surrounded by a swirl of dangerous strangeness.

Crowbone had half-turned away in his proud, unthinking fashion when the scorned miliaresion bounced on the drum, the tinkle of its final landing lost in the thunder it made. He turned, surprised.

‘What was that sound, Sea-Finn?’ he demanded and Vuokko smiled like a wolf closing in.

‘That was the sound of your enterprise, lord,’ he replied after a study of the frogs, ‘falling from your hand.’

After that, the feasting was a sullen affair coloured by Crowbone’s morose puzzlement, for now he did not know what the Sea-Finn had promised. Most of his followers only recalled the bit about him becoming king in Norway, so they were cheered.

I stood with Crowbone on the sand and dulse two days later, while his men hefted their sea-chests back on the splendid Short Serpent and got ready to sail off.

He was wrapped in his familiar white fur and a matching stare, waiting to see if terns or crows came in ones or twos, or went left or right. Only he knew what it meant.

‘All the same,’ he said finally, clasping my wrist and staring up into my gaze with his odd eyes, ‘you would do well to join me. Randr Sterki will come for you. I hear he is sworn to Styrbjorn.’

That was no surprise; Styrbjorn was the brawling nephew of my king, Eirik Segersall. Now just come into manhood, he had designs on the high seat himself when Eirik was dead and sulked when it became clear no-one else liked the idea.

Foolishly, King Eirik had given him ships and men to go off and make a life for himself and Styrbjorn now prowled up and down off Wendland on the far Baltic shore, snarling and making his intentions known regarding what he considered his birthright. Someday soon, I was thinking, he would need a good slap, but he was only a boy. I almost said so to Crowbone, then clenched my teeth on it and smiled instead.

I saw Alyosha hovering, a mailed and helmeted wet-nurse anxious to see his charge safely back on the boat. I widened my smile indulgently at Crowbone; I was arrogant then, believing Oathsworn fame and Odin’s favour shield enough against such as Randr Sterki and having no worries about Styrbjorn, a youth with barely seventeen summers on him. I should have known better; I should have remembered myself at his age.

‘Have you a tale on all this?’ I asked lightly, reminding Crowbone of the biting stories he had told us, a boy holding grown freemen in thrall out on the cold empty.

‘I have tales left,’ he answered seriously. ‘But the one I have is for later. I know birds, all the same, and they know much.’

He saw the confusion in my face and turned away, trotting towards the ship.

‘An eagle told me of troubles to come,’ he flung back over his shoulder. ‘A threat to its young, on the flight’s edge.’

The chill of that stayed with me as I watched Short Serpent slither off down the fjord and even the closeness of Thorgunna under my arm could not warm it, for I was aware of what she carried in her belly and of what her sister cradled in her arms.

Young eagles on the flight’s edge.

TWO (#ulink_b5cee949-6141-5ed8-8870-137f24824bd9)

The sun clawed itself higher every day; snow melted patch by patch, streams gurgled and I started to talk earnestly about joint efforts to harvest the sea, of ploughing and seeding cropland and how Finn could borrow my brace of oxen if he liked.

He looked at me as if I was a talking calf, then went back to drinking and hunting with Red Njal, while Onund Hnufa and Gizur went to make the Fjord Elk ready for sea and Hlenni Brimill and others fetched wood for new shields and pestered Ref to leave off tinsmithing nails against rust to put a new edge on worn blades.

After the feasting night for Crowbone, Finn had come to me and asked if the Oathsworn were going raiding after Randr Sterki, though he knew the answer before I spoke. When I confirmed it, he nodded, long, slow and thoughtful.

‘I am thinking,’ he said softly, as if the words were being dragged from him by oxen, ‘that I might have to visit Ospak and Finnlaith in Dyfflin, or perhaps go to find Fiskr in Hedeby.’

The idea of not having Finn there made me swallow and he saw my stricken face. His own was a hammer that nailed his next words into me, even though he said them with a lopsided grin.

‘It is either that or challenge for the jarl’s seat.’

Well, there it was, the fracture cracked open and visible. I bowed my head to it; the curse of Odin’s silver right enough.

‘I will stay for one more season and, if the raiding is good, it may change my mind. If not, I am thinking it best to leave, Orm.’

This would be the third season and, I was thinking, a remarkable feat of patience for the likes of Finn. Yet I was no more certain that this raiding season, which involved a long, uncomfortable voyage up and down the Baltic and sometimes into the mouths of a few rivers, pretending to trade and looking for something to steal, would be any better than the last two. There was seldom anything worthwhile for the Oathsworn, who were choking on all they already had. Yet they trained daily, making shieldwalls and breaking them, fighting in ones and threes, showing off and honing their battle skills. The lure of the prow beast, as the skalds had it, still dragged us all back to the dark water.

Now Finn wanted more jarl-work from me and threatened either to leave or take over. I could only nod, for words were ash in my mouth. After that, the promise of summer sunshine was ominous.

The women bustled the grime and stink out of Hestreng’s buildings and took clear joy in drying washing in the open air; Cormac and Helga Hiti tumbled about on sturdy legs, shouting and playing.

Into this, just after the blot offerings for the Feast of Vali, a ship slid up the fjord to us. I knew about it two hours before it arrived, which pleased me – I had set two thralls to watch in shifts and suffered Thorgunna’s waspishness over it.

‘A waste of work,’ she declared, while she and Ingrid and two female thralls hurled sleeping pallets out. ‘They could be beating the vermin out of these.’

‘I would rather know who is coming to me,’ I answered, ‘than have dust-free sleeping skins.’

‘Tell me that when next your backside is chewed by a flea,’ she spat back, blowing a wisp of hair which had fought free of her head-cloth down onto her nose. ‘And if I am doing this, I am not making butter – you will feel differently when you have to choke on dry bread.’

From this, I knew she was happy that winter was over and that she had life in her – life I would rather see grow than be burned out if Randr Sterki arrived and we did not know of it. I said as much and had her snort back at me but when word came of this ship, I saw her stiffen and turn and start chivvying thralls and Ingrid to fetch the children, gathering them to her like a hen with chicks.

I let her for a while, though I knew it was no threat; the sail was large and plainly marked with Jarl Brand’s sign and unless someone had taken Black Eagle from him intact – as unlikely as wings on a fish – then it was himself coming up the fjord.

He came up showing off, too, the sail flaked down and the oars bending as his men made Black Eagle cream through the sea. Then, at a single command we all heard as we stood watching on the shore, the oars were lifted clear and taken in until only a quarter of their length was left.

Along this sprang a figure, dancing and bouncing from stem to stern; we all cheered, knowing it was probably his prow man Nes-Bjorn, called Klak – Peg – because he was shaped like one, having oar-muscled shoulders, but skinny hips and legs. He could walk the oars with those skinny legs, all the same, swinging from one side to the other on a loose line.

The crew were equally skilled and slid the thirty-oar drakkar neatly to the stone slipway, where the Fjord Elk was propped up, with scarcely a dunt on its gilded side. Men spilled ashore then, shouting greetings to those who went to meet them. Thorgunna sighed, scattered the children and roared for thralls; there were sixty new mouths to feed and precious little left in the stores.

She stopped scowling, all the same, when she found what Jarl Brand had brought. He came off smiling, as usual, bone-white as he had always been, wearing a gold-embroidered black tunic trimmed with marten, fine wool breeks that flared over kidskin boots and his neck and arms heavy with amber and silver.

At his side trotted a boy as white as Brand was and people stared for he was Cormac’s double, only older, at least five; Aoife kept her head meekly down and said nothing. On Jarl Brand’s other side was a strange little man dressed in a black serk to his toes, young, moon-faced and glum.

‘My son,’ Brand declared gruffly, indicating the sombre, white-haired boy. ‘I bring him to you to foster.’

That took my breath away and I was still struggling to suck more in when he indicated the moon-face on his other side.

‘This is one called Leo,’ he said. ‘A Greek monk of sorts, from the Great City.’

I shot Jarl Brand a look and he chuckled at it, shaking his head so that his moustaches trembled like melting icicles.

‘No, I am not turned to the White Christ,’ he replied. ‘This Greek is sent by the Emperor to take greetings to our king. I picked him up in Jumne.’

‘Like a sack of grain,’ agreed the man with a slight smile. ‘I have been stacked and shipped ever since.’

It took me a moment to realise he had spoken Greek and that Jarl Brand had been talking Norse, which meant this Leo knew Norse and also that both Jarl Brand and I understood Greek. Jarl Brand chuckled as I brought Thorgunna, introduced her and had her take Leo into the hall.

‘Watch him,’ Brand said, tight into my ear as the monk reeled away from us, his legs still on the sea. ‘He is more than a monkish scribbler, which he does all the time. He is clever and watches constantly and knows more than he reveals.’

I agreed, but was distracted by what was now unloading from Black Eagle – two women, one young and fat with child, the other older, almost as fat and fussing round her like a gull round a chick.

Jarl Brand caught my stare and grunted, the sound of a man too weighted to speak.

‘Sigrith,’ he said, pulling me away by the elbow. ‘Fresh returned from visiting her father, Mieczyslaw, King of the Polans, and near her dropping time – which is why we are here. King Eirik wants his son born in Uppsalla.’

I blinked and gawped, despite myself. This was Sigrith, splendid as a gilded dragon-head, no more than eighteen and a queen, yet young and bright-eyed and heavy with her first bairn; she was just a frightened child of a Slav tribe from the middle of nowhere.

‘The fat one is Jasna, who was her nurse when she lived with her people,’ Jarl Brand went on, miserably. ‘I am charged with bringing them to the king, together with whatever the queen unloads, safe and well.’

‘That’s a cargo I could do without,’ I answered without thinking, then caught his jaundiced eye. We both smiled, though it was grim – then I noticed the girl at the back. I had taken her for a thrall, in her shapeless, colourless dress, kerchief over what I took to be a shaved head, but she walked like she had gold between her legs. Thin and small, with a face too big for her and eyes dark and liquid as the black fjord.

‘She is a Mazur,’ Jarl Brand said, following my gaze. ‘Her name turns out in Slav to be Chernoglazov – Dark Eye – but the queen and her fat cow call her Drozdov, Blackbird.’

‘A thrall?’ I asked uncertainly and he shook his head.

‘I was thinking that, too, when I saw her first,’ he replied with a grunt of humour, ‘but it is worse than that – she is a hostage, daughter of a chief of one of the tribes that Mieczyslaw the Pol wants to control to the east of him. She is proud as a queen, all the same, and worships some three-headed god. Or four, I am never sure.’

I looked at the bird-named woman – well, girl, in truth. A long way from home to keep her from being snatched back, held as surety for her tribe’s good behaviour, she had a look half-way between scorn and a deer at the point of running. Truly, a cargo I would not wish to be carrying myself and did not relish it washing up on my beach.

However, it had an unexpected side to it; Thorgunna, presented with the honour of a queen and a jarl’s fostri in her house, beamed with pleasure at Jarl Brand and me both, as if we had personally arranged for it. Brand saw it and patted my shoulder soothingly, smiling stiffly the while.

‘This will change,’ he noted, ‘when Sigrith shows how a queen expects to be treated.’

His men unloaded food and drink, which was welcomed and we feasted everyone on coal-roasted horse, lamb, fine fish and good bread – though Sigrith turned her nose up at such fare, whether from sickness or disgust, and Thorgunna shot me the first of many meaningful glances across the hall and fell to muttering with her sister.

Since the women were full of bairns, one way and another, they sat and talked weans with the proud Sigrith, leaving Finn and Botolf and me with Jarl Brand and his serious-faced son, Koll.

The boy, ice-white as his da, sat stiffly at what must have been a trial for one so young – sent to the strange world of the Oathsworn’s jarl, ripped from his ma’s cooing, yet still eager to please. He sat, considered and careful over all he did, so as not to make a mistake and shame his father. At one and the same time it warmed and broke your heart.

There was no point in trying to talk the stiff out of him – for one thing the hall roared and fretted with feasting, so that you had to shout; it is a hard thing to be considerate and consoling when you are bellowing. For another, he was gripped with fear and saw me only as the huge stranger he was to be left with and took no comfort in that.

In the end, Thorgunna and Botolf’s Ingrid swept him up and into the comfort of their mothering, which brought such relief to his face that, in the end, he managed a laugh or two. For his part, Jarl Brand smiled and drank and ate as if he did not have a care, but he had come here to leave me the boy and, like all fathers, was agonising over it even as he saw the need.

Leo the monk had seen all this, too, which did not surprise me. A scribbler of histories, he had told me earlier, wanting to know tales of the siege at Sarkel and the fight at Antioch from one who had been at both. Aye, he was young and smiling and seal-sleek, that one – but I had dealt with Great City merchants and I knew these Greek-Romans well, oiled beards and flattery both.

‘I never understood about fostering,’ Leo said, leaning forward to speak quietly to me, while Brand and Finn argued over, of all things, the best way to season new lamb; Brand kept shooting his son sideways glances, making sure he was not too afraid. ‘It is not, as it is with us in Constantinople, a polite way of taking hostages.’

He regarded me with his olive-stone eyes and his too-ready smile, while I sought words to explain what a fostri was.

‘Jarl Brand does me honour,’ I told him. ‘To be offered the rearing of a child to manhood is no light thing and usually not done outside the aett.’

‘The…aett?’

‘Clan. Family. House,’ I answered in Greek and he nodded, picking at bread with the long fingers of one hand, stained black-brown from ink.

‘So he has welcomed you into his house,’ Leo declared, chewing with grimaces at the grit he found. ‘Not, I surmise, as an equal.’

It was true, of course – accepting the fostering of another’s child was also an acceptance that the father was of a higher standing than you were. But this bothered me much less than the fact that Leo, the innocent monk from the Great City and barely out of his teens, had worked this out. Even then, with only a little more than twenty years on him, he had a mind of whirling cogs and toothed wheels, like those I had seen once driving mills and waterwheels in Serkland.

He also ate the horse, spearing greasy slivers of it on a little two-tined eating fork. This surprised me, for Christ followers considered that to be a pagan ritual and would not usually do it. He saw me follow the food to his mouth and knew what I was thinking, smiling and shrugging as he chewed.

‘I shall do penance for this later. The one thing you learn swiftly about being a diplomat is not to offend.’

‘Or suffer for being a Christ priest in a land of Odin,’ interrupted Jarl Brand, subtle as a forge hammer. ‘This is Hestreng, home of the Oathsworn, Odin’s own favourites. Christ followers find no soil for their seed here, eh, Orm?

‘Bone, blood and steel,’ he added when I said nothing. The words were from the Odin Oath that bound what was left of my varjazi, my band of brothers; it made Leo raise his eyebrows, turning his eyes round and wide as if alarmed.

‘I did not think I was in such danger. Am I, then, to be nailed to a tree?’

I thought about that carefully. The shaven-headed priests of the Christ could come and go as they pleased around Hestreng and say what they chose, provided they caused no trouble. Sometimes, though, the people grew tired of being ranted at and chased them away with blows. Down in the south, I had heard, the skin-wearing trolls of the Going folk took hold of an irritating one now and then and sacrificed him in the old way, nailed to a tree in honour of Odin. That Leo knew of this also meant he was not fresh from a cloister.

‘I heard tales from travellers,’ he replied, seeing me study him and looking back at me with his flat, wide-eyed gaze while he lied. ‘Of course, those unfortunate monks were Franks and Saxlanders and, though brothers in Christ – give or take an argument or two – lacking somewhat in diplomacy.’

‘And weaponry,’ I added and we locked eyes for a moment, like rutting elks. At the end, I felt sure there was as much steel hidden about this singular monk as there was running down his spine. I did not like him one bit and trusted him even less.

Now I had been shown the warp and weft of matters there was nothing left but to nod and smile while Cormac, Aoife’s son, filled our horns. Jarl Brand frowned at the sight of him, as he always did, since the boy was as colourless as the jarl himself. White to his eyelashes, he was, with eyes of the palest blue, and it was not hard to see which tree the twig had sprouted from. When Cormac filled little Koll’s horn with watered ale, their heads almost touching, I heard Brand suck in air sharply.

‘The boy is growing,’ he muttered. ‘I must do something about him…’

‘He needs a father, that one,’ I added meaningfully and he nodded, then smiled fondly at Koll. Aoife went by, filling horns and swaying her hips just a little more, I was thinking, so that Jarl Brand grunted and stirred on his bench.

I sighed; after some nights here, the chances were strong that, this time next year, we would have another bone-haired yelper from Aoife, another ice-white bairn. As if we did not have little eagles enough at the flight’s edge…

In the morning, buds unfolded in green mists, sunlight sparkled wetly on grass and spring sauntered across the land while the Oathsworn hauled the Fjord Elk off the slipway, to rock gently beside Black Eagle. Now was the moment when the raiding began and, on the strength of it, Finn would go or stay; that sank my stomach to my boot tops.

It was a good ship, our Elk – fifteen benches each side and no Slav tree trunk, but a properly straked, oak-keeled drakkar that had survived portage and narrow rivers on at least two trips to Gardariki.

All the same, it was a bairn next to Black Eagle, which had thirty oars a side and was as long as fifteen tall men laid end to end. It was tricked out in gilding, painted red and black, with the great black eagle prow and a crew of growlers who knew they had the best and fastest ship afloat. They and the Oathsworn chaffered and jeered at each other, straining muscle and sinew to get the Elk into the water, then demanding a race up the fjord to decide which ship and crew was better.

Into the middle of this came the queen, ponderous as an Arab slave ship, with Thordis and Ingrid and Thorgunna round her and Jasna lumbering ahead. As this woman-fleet sailed past me, heading towards Jarl Brand, Thorgunna raised weary eyebrows.

The jarl had his back to Queen Sigrith as she came up and almost leapt out of his nice coloured tunic when she spoke. Then, flustered and annoyed at having been so taken by surprise, he scowled at her, which was a mistake.

Sigrith’s voice was shrill and high. Before, it might have been mistaken for girlish, but fear of childbirthing had sucked the sweetness out of it and her Polan accent was thick, so her demands to know when they were sailing from this dreadful place to one which did not smell of fish and sweaty men, had a rancid bite.

If Jarl Brand had an answer, he never gave it; one of my lookout thralls came pounding up, spraying mud and words in equal measure; a faering was coming up the fjord.

Such boats were too small to be feared, but the arrival of it was interesting enough to divert everyone, for which Brand was grateful. Yet, when it came heeling in, sail barely reefed and obviously badly handled, I felt an anchor-stone settle in my gut.

There were arrow shafts visible, and willing men splashed out, waist deep, to catch the little craft and help the man in it take in sail, for he was clearly hurt. They towed it in; two men were in it and blood sloshed in the scuppers; one man was dead and the survivor gasping with pain and badly cut about.

‘Skulli,’ Brand said, grim as old rock, and the anchor-stone sank lower; Skulli was his steward and I looked at the man, head lolling and leaking life as the women lifted him away to be cared for.

Brand stopped them and let Skulli leak while he gasped out the saga of what had happened. It took only moments to tell – Styrbjorn had arrived, with at least five ships and the men for them, clearly bound for a slaughter against his uncle’s right-hand man, to make a show of what he was capable of if things did not go his way.

Jarl Brand’s hall was burning, his men dead, his thralls fled, his women taken.

The black dog of it crushed everyone for a moment, then shook itself; men bellowed and all was movement. I saw Finn’s face and the mad joy on it was clear as blood on snow.

While Thorgunna and Thordis hauled Skulli off and yelled out for Bjaelfi to bring his skill and healing runes, Brand took my arm and led me a little way aside while men rushed to make Black Eagle ready. His face was now as bone-coloured as his hair.

‘I have to go to King Eirik,’ he declared. ‘Add my ship to his and what men I can sweep up on the way. Styrbjorn, if he is stupid, will stay to fight us and we will kill him. If not, he will flee and I will chase him and make him pay for what he has done.’

‘I can have the Elk ready in an hour or two,’ I said, then stopped as he shook his head.

‘Serve me better,’ he answered. ‘Call up your Oathsworn to this place. Look after the queen. I can hardly take her with me.’

That stopped my mouth, sure as a hand over it. He returned my look with a cliff of a face and eyes that said there would be no arguing; yet he cracked the stone of him an instant later, when he shot a sideways glance to where Koll watched, round-eyed, as men bustled. I did not need him to say more.

‘The queen and son both, then,’ I replied, feeling the sick dread of what would happen if Styrbjorn sent ships here, for it would take time to send out word to the world that Hestreng needed the old Oathsworn back. Jarl Brand saw it, too, and nodded briefly.

‘I will leave thirty of my crew – I wish it were more.’

It was generous, for the ones he had left would break themselves to run Black Eagle home, with no relief. It was also a marker of what he feared and I forced a smile.

‘Who will attack the Oathsworn?’ I countered, but there was no mirth in the twist of a grin he gave, turning away to bawl orders to his men.

There was a great milling of movement and words; I sent Botolf stumping off to bring the thirty of Jarl Brand’s crew. They stood forlorn and grim on the shore as their oarmates sailed away – but there was none more cliff-faced and black-scowling than Finn, watching others sail away to the war he wanted. Then I gathered up Botolf’s daughter, little red-haired Helga, and made her laugh, as much to make me feel better as her. Ingrid smiled.

Jasna waddled up to me, the queen moving ponderously behind her, made bulkier still by furs against the chill.

‘Her Highness wishes to know what blot you will make for the jarl’s journey,’ she demanded and her tone made me angry, since she was a thrall when all was said and done. I tossed Helga in the air and made her scream.

‘Laughter,’ I answered brusquely. ‘The gods need it sometimes.’

Jasna blinked at that, then went back to the queen, walking like a loaded pack pony; there were whispers back and forth. Out of the corner of my eye I saw Thorgunna scowling at me and in answer I carried on playing with the child.

‘This is not seemly,’ said an all-too familiar voice, jerking me from Helga’s gurgles. The queen stood in front of me, mittened hands folded over her swollen belly, frowning.

‘Seemly?’

She waved a small hand, like a little furred paw in the mitten. Her face was sharp as a cat’s and would have been pretty save for the lines at the edges of her mouth.

‘You are godi here. This is not…It has no…dignitas.’

‘You sound like a Christ follower,’ I answered shortly, putting Helga down; she trundled off towards her mother, who gathered her up. I saw Thorgunna closing on us, fast as a racing drakkar.

‘Christ follower!’

It was an explosion of shriek and I turned my head from it, as you would from an icy blast. Then I shrugged, for this queen, her young and beautiful face twisted with outrage, annoyed me more and more. I was annoyed, too, to have forgotten that the Christ godlet had been foisted on her father and his people; like the rest of them, she resented this.

‘They also confuse misery and prayer,’ I managed to answer and heard a chuckle I recognised as Leo. Thorgunna bustled up, managing to elbow me in the ribs.

‘Highness,’ she said to Sigrith, with a sweet smile. ‘I have everything prepared – what do men know of sacrifice?’

Mollified, the queen allowed herself to be led away, followed by Jasna, who threw me a venomous glare. The ever-present, ever-silent Mazur girl followed after, but paused to shoot me a quick glance from those dark eyes; afterwards, I realised what had made me remember it. It was the first time she had looked directly at anyone at all.

At the time, I heard a little laugh which distracted me from thoughts of the girl and turned my head to where Leo watched, swathed in a cloak, hands shoved deep inside its folds.

‘I thought traders of your standing had more diplomacy,’ he offered and I said nothing, knowing he had the right of it and that my behaviour had been, at best, childish.

‘But she galls, does she not?’ he added, as if reading my mind.

‘Even less soil there than here for your Christ seed,’ I countered. ‘Even if you get to the court. Your visit to Uppsalla is proving a failure.’

He smiled the moon-faced smile of a man who did not think anything he did was a failure, then inclined his head and moved off, leaving me with the last view of Black Eagle, raising sail and speeding off into the grey distance.

I felt rain spot my neck and shivered, looked up to a pewter sky and offered a prayer to bluff Thor and Aegir of the waves and Niord, god of the coasts, for a good blow and some tossing white-caps. A storm sea would keep us safe…

I rose in the night and left my sleeping area, mumbling to a dreamy Thorgunna about the need for a privy, which was a lie. I stepped through the hall of grunting and snores and soft stirrings in the dark, past the pitfire’s grey ash, where little red eyes watched me step out of the hall.

The sharp air made me wish I had brought a cloak, made me wonder at this foolishness. There was rain in that air, yet no storm and the fear of that lack filled me. Dreams I knew – Odin’s arse, I had been hag-ridden by dreams all my life – but this was strange, a formless half-life, a draugr of a feeling that ruined sleep and nipped my waking heels.

Never before or since have I felt the power of the prow beast on a raiding ship as it locks jaws with the spirit of the land – but I felt them both that night, muscled and snarling shadows in the dark. Even then, I knew Randr Sterki was coming.

Yet the world remained the same, etched in black and silver, misted in shreds even in the black night. A dog fox barked far out on the pasture; the great dark of Ginnungagap still held the embers of Muspelheim, flung there by Odin’s brothers, Vili and Ve. Between scudding clouds, I found Aurvandill’s Toe and the Eyes of Thjazi after a search, but easily found the Wagon Star, which guides prow beasts everywhere. The one on Randr’s ship would be following it like a spooring wolf.

There was a closer light from the little building that housed Ref’s forge, a soft glow and I moved to it, drawn by the hope of heat. A few steps from it, the voices halted me – I have no idea why, since they were ones I knew; Ref was there and Botolf with him and the thrall boy, Toki.

Ref was nailing, which was a simple thing but a steading needed lots of them and he clearly took comfort in the easy repetitive task; he took slim lengths of worked bog-iron, flared one end and pointed the other, two taps for one, four for the other, then a plunge into the quench and a drop into a box. Even for that simple task, he kept the light in the forge dim, so that he could read the colour of the fire and the heated iron.

Toki, a doll-like silhouette with his back to me, worked the bellows and hugged his reedy arms between times, chilled despite the flames in his one-piece kjartan and bare feet, his near-bald head shining in the red light.

The place had the burned-hair smell of charred hooves, braided with the tang of sea-salt, charcoal and horse piss. In the dim light of the forge-fire and a small horn lantern above Botolf’s head, Ref looked like a dwarf and Botolf a giant, the one forging some magical thing, the other red-dyed with light and speaking in a low rumble, like boulders grinding.

‘That dog fox is out again,’ he was saying. ‘He’s after the chickens.’

‘That’s why we coop them,’ Ref replied, concentrating. Tap, tap. Pause. Tap, tap, tap, tap. Plunge and hiss. He picked up another length.

‘He won’t come near. He is afraid of the hounds,’ Botolf replied, shifting his weight. He nudged Toki, who pumped the bellows a few times.

‘Why is he afraid?’ the boy asked. ‘He can run.’

‘Because the hounds run slower but longer and will kill him,’ answered Ref. ‘So would you be afraid.’

The boy shivered. ‘I am afraid even in my dreams,’ he answered and Botolf looked at him.

‘Dreams, little Toki? What dreams? My Helga has dreams, too, which make her afraid. What do you dream?’

The boy shrugged. ‘Falling from a high place, like Aoife says my da did.’

Botolf nodded soberly, remembering that Toki had been fathered by a thrall called Geitleggr, whose hairy goat legs had given him the only name he had known – but none of the animal’s skill when it came to gathering eggs on narrow ledges. His mother, too, had died, of too much work, too little food and winter and now Aoife looked out for Toki, as much as anyone did.

‘I like high places,’ Botolf said, seeking to reassure the boy. ‘They are in nearly all my dreams.’

Ref absently pinched out a flaring ember on his already scorch-marked old tunic and I doubted if his horn-skinned fingers felt it. He never took his eyes from the iron, watching the colour of the flames for the right moment, even on just a nail.

Tap, tap, tap, tap – plunge, hiss.

‘What are they, then, these dreams of yours, Botolf?’ Ref wanted to know, sliding another length of bog-iron into the coals and jerking his chin at Toki to start pumping.

Botolf tapped his timber foot on the side of the oak stump which held the spiked anvil.

‘Since I got this, wings,’ he answered. ‘I dream I have wings. Big black ones, like a raven.’

‘What does it feel like?’ Toki asked, peering curiously. ‘Is it like a real leg?’

‘Mostly,’ answered Botolf, ‘except when it itches, for you cannot scratch it.’

‘Does it itch, then?’ Ref asked, pausing in wonder. ‘Like a real leg?’

Botolf nodded.

‘Did some magic woodworker make it so that it itched?’ Toki wanted to know and Botolf chuckled.

‘If he did, I wish he would come back and unmake it – or at least let me scratch. I dream of that when I am not dreaming of wings.’

‘Does no-one dream of proper things any more?’ Ref grumbled, turning the bog-iron length in the coals. ‘Wealth and fame and women?’

‘I have all three,’ Botolf answered. ‘I have no need of that dream.’

‘I dream of food most often,’ Toki admitted and the other two laughed; boys seldom had enough to eat and thralls never did.

‘Sing a song,’ Ref said, ‘soft now, so as not to wake everyone. Pick a good one and it will go into the iron and make the nails stronger.’

So Toki sang, a child song, a soft song of the sea and being lost on it. The wave of it left me stranded at the edge of darkness, icy and empty and wondering why he had chosen that of all songs and if the hand of Odin was in it.

I had heard that song before, in another place. We had come ashore in the night, blacker than the night itself with hate and fear, unseen, unheard until we raved down on Klerkon’s steading on Svartey at dawn – a steading like this, I remembered, sick and cold. Only one fighting man had been there and he had been easily killed by Kvasir and Finn.

Things had been done, as they always were in such events, made more savage because it was Klerkon we hunted and he had stolen Thorgunna’s sister, Thordis. He was not there, but all his folk’s women and bairns were and, prowling for him, I had heard the singing, sweet in the dawn’s dim, a song to keep out the fear.

I heard it stop, too. I had come upon the great tangle-haired growler who had cut it out of the girl’s throat with a single slash, his blade clotted with sticky darkness and strands of hair. He had turned to me, all beard and mad grin and I had known him at once – Red Njal, limping Red Njal, who now played with Botolf’s Helga and carved dolls for her.

Beyond, all twisted limbs and bewildered faces, were the singer’s three little siblings: blood smoked in the hearthfire coals and puddled the stones. The thrall-nurse was there, too, forearm hacked through where she had flung up her arms in a last desperate, useless attempt to ward off an axe edge. Red Njal was on his knees in the blood, rifling for plunder.

There were shouts then, and I followed them; outside lay a plough ox still dying, great head flapping and blood bubbling from its muzzle, the eyes wide and rolling. Across the heaving, weakly thrashing body of it, as if on some box-bed, three men stripped a woman to pale breasts and belly, down to the hair between her legs, while she gasped, strength almost gone but fighting still.

Her blonde braids flailed as her head thrashed back and forth and two of the men tried to hold her, while the third fought down his breeches and struggled to get between her legs. She spat crimson at him and he howled back at her and smacked her in the mouth, so that her head bounced off the twitching flank of the ox, which tried to bawl and only hissed out more blood.

They panted and struggled, like men trying to fit a new wheel on a heavy cart, calling advice, insults, curses when the ox shat itself, working steadily towards the inevitable…then the one between her legs, the one I knew well, lost his patience, unable to hold her and rid himself of the knee she kept wedging in his way.

He hauled a seax from his boot and slit her throat, so that she gug-gug-gugged on her own blood and started to flop like a fish. The knee dropped; the man stuck the seax in the ox and his prick in the woman and started pumping while the others laughed.

The boy came from nowhere, from the dark where he had seen it all, from where he had watched his mother, Randr Sterki’s wife, die. He came like a hare and snatched up the seax, while the man pumped and pumped, gone frantic and unseeing and the woman gurgled and died beneath him.

My blade took the back of the boy’s skull clean off, an instant before he brought the seax down. I watched the back of his head fly in the air, the hair on it like spider legs, the gleet and brain and blood arcing out to splash the dying woman’s last lover, who jerked himself away and out of her, gawping, his prick hanging like a dead chicken’s neck.

‘Odin’s arse…well struck, Orm. That little hole would have had me, liver and lights, for sure.’

Grinning, Finn hauled his breeks up and grabbed his seax from the boy’s gripping hand, so that, for a moment, it looked as if the lad was raising himself up. But he was dead, slumped across his mother and Finn spat on him before stumping off into the dark…

‘Why are you standing out there?’

The voice raked me back to the night and the forge. All the heads had turned towards me and Botolf chuckled. Toki, half-turned, was bloodied by the forgelight and, for a moment, I saw the face of the boy I had killed. Toki was the same age. Too young to die. Yet Randr’s boy would have killed Finn – had once laughed as he helped his mother scrape Crowbone’s head raw, then chain him to the privy as punishment for running away. What the Norns weave is always intricate, but it can be as dark and ugly as it is beautiful.

‘Listeners at the eaves hear no good of themselves,’ Botolf intoned. Toki dropped from his perch, breaking the spell.

‘Sleep comes hard,’ Ref grunted, ‘too many farters and snorers in the hall.’

We all knew that was not the reason I was here, but I went along with the conspiracy, grunting agreement.

Ref, seeing the flames change colour, lifted his head. ‘Back to the bellows, boy,’ he called, but Toki kept staring – he pointed behind me, away into the dark land where I had set watchers and fire.

‘What is that light?’ he asked.

I did not need to turn, felt the sick, frantic heat of that warning beacon though it was miles away. When I spoke I stared straight at Botolf, so he would know, would remember what he had been told of Klerkon’s steading on Svartey.

‘That light is men who kill bairns and fuck their mother on a dead ox,’ I said, harsh as a crow laugh.

‘Men like us.’

Men like us, following their prow beast up the fjord in a ship called Dragon Wings, grim with revenge, hugging a secret to them with savage glee, for they did not want a fair fight, only slaughter.

You can only wear what the Norns weave, so we sent everyone else off into the mountains and worked the Elk out to meet Randr Sterki. Men struggled and died screaming battle cries and bloodlust there on the raven-black, slow-shifting fjord; the prow beasts bobbed and snarled at each other as men struggled and died in the last light of a hard day – and both sides found the secret of the Roman Fire that burns even water.

THREE (#ulink_8c310fad-b139-5ba2-9f7c-c1aa0da50401)

HESTRENG, after the battle

The vault of his head was charred to black ruin and stank, a jarring on the nose and throat but one which had helped bring me back to coughing life. My throat burned, my chest felt tight and my ears roared with the gurgle of water. It was night, with a fitful, shrouded moon.

I blinked; his hands were gone, melted like old tallow down to the bone and his scalp had slipped like some rakish, ratfur cap, the one remaining eye a blistered orb that bulged beneath the fused eyelids, the face a melted-tallow mass of sloughed brow and crackled-black.

‘Nes-Bjorn,’ said a voice and I turned to it. Finn tilted his chin at the mess; the claw of one hand still reached up as if looking for help.

‘Three ladies, over the fields they crossed,’ he intoned. ‘One brought fire, two brought frost. Out with the fire, in with the frost. Out, fire! In, frost!’

It was an old charm, used on children who had scorched or scalded themselves, but a little late for use on the ruin that had been Nes-Bjorn.