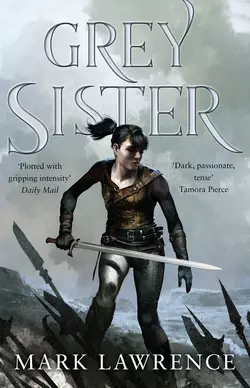

Grey Sister

Mark Lawrence

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Фэнтези про драконов

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 1552.95 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: Second novel in the brilliant new series from the bestselling author of PRINCE OF THORNS.In Mystic Class Nona Grey begins to learn the secrets of the universe. But so often, knowing the truth just makes our choices harder. Before she leaves the Convent of Sweet Mercy, Nona must choose her path and take the red of a Martial Sister, the grey of a Sister of Discretion, the blue of a Mystic Sister or the simple black of a Bride of the Ancestor, entailing a life of prayer and service.Standing between her and these choices are the pride of a thwarted assassin, the ambition of a would-be empress wielding the Inquisition like a blade, and the vengeance of the empire’s richest lord.As the world narrows around her, and her enemies attack her using the very system she has sworn to, Nona must forge her own path in spite of the pulls of friendship, revenge, ambition, and loyalty.In all this only one thing is certain. There will be blood.