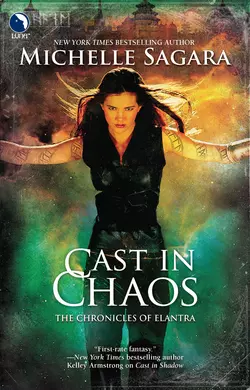

Cast in Chaos

Michelle Sagara

Kaylin Neya is a Hawk, part of the elite force tasked with keeping the City of Elantra safe. Her past is dark, her magic uncontrolled and her allies unpredictable. And nothing has prepared her for what is coming, when the charlatans on Elani Street suddenly grow powerful, the Oracles are thrown into an uproar and the skies rain blood… The powerful of Elantra believe that the mysterious markings on Kaylin’s skin hold the answer, and they are not averse to using her – however they have to – in order to discover what it is.Something is coming, breaking through the barriers between the worlds. But is it a threat that Kaylin needs to defend her city against – or has she been chosen for another reason entirely?“Sagara swirls mystery and magical adventure together with unforgettable characters." –Publishers Weekly on Cast in Silence

Praise for New York Times bestselling author MICHELLE SAGARA and THE CHRONICLES OF ELANTRA series

“No one provides an emotional payoff like Michelle Sagara. Combine that with a fast-paced police procedural, deadly magics, five very different races and a wickedly dry sense of humor—well, it doesn’t get any better than this.”

—Bestselling author Tanya Huff

“Intense, fast-paced, intriguing, compelling and hard to put down…unforgettable.”

—In the Library Reviews on Cast in Shadow

“Readers will embrace this compelling, strong-willed heroine with her often sarcastic voice.”

—Publishers Weekly on Cast in Courtlight

“The impressively detailed setting and the book’s spirited heroine are sure to charm romance readers as well as fantasy fans who like some mystery with their magic.”

—Publishers Weekly on Cast in Secret

“Along with the exquisitely detailed worldbuilding, Sagara’s character development is mesmerizing. She expertly breathes life into a stubborn yet evolving heroine. A true master of her craft!”

—RT Book Reviews (4 ½ stars) on Cast in Fury

“With prose that is elegantly descriptive, Sagara answers some longstanding questions and adds another layer of mystery. Each visit to this amazing world, with its richness of place and character, is one to relish.”

—RT Book Reviews (4 ½ stars) on Cast in Silence

Cast in Chaos

Michelle Sagara

www.millsandboon.co.uk (http://www.millsandboon.co.uk)

AUTHOR NOTE

There are, in fantasy, two types of series. One is the extended single story that, with multiple viewpoints and various plot threads, spreads out over several volumes. The other is a connected series of stand-alone stories which feature more or less the same characters facing different situations; mysteries are characteristically this type of series. THE CHRONICLES OF ELANTRA is the second type of series as well. Kaylin Neya, the main character, is an Elantran police officer, and her job is to investigate crimes and solve them—although both the problems and the solutions in a world with winged mortals, Dragons and large, furred Leontines tend to be less mundane than the problems a real-world precinct would generally face. I hope that someone picking up any volume of the series would be able to follow the story and the characters from the beginning of the book to the end.

But.

In this second type of series, the individual story arcs are often small; it’s the character arcs that have room to grow, because ideally what your characters experience for good or ill causes trickle-down changes that continue on into the future. The Kaylin of Cast in Shadow (the first of THE CHRONICLES OF ELANTRA) and the Kaylin of the book you now hold in your hands is substantially the same person, but she has learned to let go of some of her earlier prejudices because of the events of subsequent books (for example, Cast in Secret, in which she confronts her visceral dislike of the Tha’alani, the racial telepaths).

Some of the events of previous books also cause emotional ripples in her life, and while she is facing an entirely different threat in Cast in Chaos, she’s come far enough to begin to acknowledge some of them. If this is the first time you’ve joined her, welcome to Elantra; if you’ve been following her all along, my heartfelt thanks.

CAST IN CHAOS

For my Uncle Shoichi, with gratitude

CONTENTS

CHAPTER 1

CHAPTER 2

CHAPTER 3

CHAPTER 4

CHAPTER 5

CHAPTER 6

CHAPTER 7

CHAPTER 8

CHAPTER 9

CHAPTER 10

CHAPTER 11

CHAPTER 12

CHAPTER 13

CHAPTER 14

CHAPTER 15

CHAPTER 16

CHAPTER 17

CHAPTER 18

CHAPTER 19

CHAPTER 20

CHAPTER 21

CHAPTER 22

CHAPTER 23

CHAPTER 24

CHAPTER 25

CHAPTER 26

CHAPTER 27

CHAPTER 28

CHAPTER 29

CHAPTER 30

CHAPTER 31

CHAPTER 1

The Halls of Law occupied real estate that the merchants’ guild salivated over every time discussion about tax laws came up, and for that reason, if no other, Private Kaylin Neya was proud to work in them. The building sat in the center of the city, its bulk overshadowed by three towers, atop which—in the brisk and heavy winds of the otherwise clear day—flags could be seen at the heights. It was the only building, by Imperial decree, which was allowed this much height; the Emperor considered it a personal statement. She would probably have been slightly prouder if she’d managed to make Corporal, but she took what she could get.

What she could get, on the other hand, could be a bit disconcerting on some days. She approached the guards at the door—today Tanner and Gillas were at their posts—and stopped before she’d passed between them. They were giving her funny looks, and she was on time. She’d been on time for four days running, although one emergency with the midwives’ guild had pulled her off active duty in the middle of the day, but the looks on their faces didn’t indicate a lost betting pool.

“What’s up?” she asked Tanner. She had to look up to ask it; he was easily over six feet in height, and he didn’t slouch when on duty.

“You’ll find out,” he replied. He was almost smirking.

The problem with coming to the Hawks as an angry thirteen-year-old with a lot of attitude was that the entire force felt as if they’d watched you grow up. This meant the entire damn force took an interest in your personal business. She cursed Tanner under her breath, and left his chuckle at her back.

It was only about ten feet from her back when she ran into Corporal Severn Handred. Who just happened to be loitering in the Aerie, under the shadows of the flying Aerians, who were practicing maneuvers that no other race on the force could achieve without a hell of a lot of magic, most of which would require postmaneuver paperwork that would keep them grounded for weeks. The Emperor was not a big fan of magic that wasn’t under his personal control.

Kaylin, her wrist weighted by a few pounds of what was ostensibly gold, knew this firsthand. The bracer—studded with what were also ostensibly gemstones, and in and of itself more valuable than most of the force on a good day, which would be a day when their Sergeant wasn’t actively cursing the amount of money being wasted employing their sorry butts—was also magical. It was older than the Empire.

No one knew how it worked—or at least that’s what was claimed—but it kept random magic neutralized. Kaylin had been ordered to wear it, and on most days, she did.

Severn looked up as she approached him. “You’re on time,” he said, falling into an easy step beside her.

“And the world hasn’t ended,” she replied. “Betting? It’s four days running.” It was a betting pool she’d been excluded from joining.

He grinned, but didn’t answer, which meant yes, he was betting, and no, he hadn’t lost yet.

“If you win, you can buy me lunch.”

He raised a brow. “You’re scrounging for lunch this early in the month?”

“Don’t ask.”

He laughed.

“Instead,” she continued, “tell me why you’re here.”

“I work here.”

“Ha, ha. You don’t usually loiter in the Aerie, waiting for me to walk by.” In fact, if it was something that was a matter of life or death, or at least keeping her job, he was more proactive: he’d show up at her apartment and throw her out of bed.

“Loitering and waiting are not considered—”

“Tanner was smirking.”

Severn winced. “An official courier came by the office this morning.”

“Official courier?”

“An Imperial Courier.”

“Please tell me it had nothing to do with me,” she said, without much hope.

“You want me to lie?”

She snorted. “Is Marcus in a mood?”

“Let’s just say he didn’t seem overly surprised.” Which wasn’t much of an answer if the one you wanted was No.

Teela was in the office and at her desk, which was generally a bad sign. She was also on break, which meant she was lounging on a chair that was balanced on its back two legs, and watching the door. Tain was somewhere else, which meant Kaylin only had to deal with one of the Barrani Hawks she sometimes counted as friends. On this particular morning, she couldn’t remember why, exactly.

The fact that Teela rose—gracefully, because it was impossible for a Barrani not to be graceful—the minute she laid emerald eyes on Kaylin made it clear who she’d been watching for. The fact that she was smiling as she sauntered across the usual chaos of the office meant she was amused. This didn’t mean that the news for Kaylin was good, on the other hand.

“Good morning, Private Neya,” the window said. “It is a bright and sunny day, but rain is expected in the late afternoon. Please dress accordingly while you are on duty.”

Teela took one look at Kaylin’s raised brows and laughed out loud.

Kaylin said a few choice words in Leontine.

“Please be aware that this is a multiracial office, and the terms that you are using might give offense to some of your coworkers,” the same window chided.

Kaylin’s jaw nearly hit the floor.

“Apparently,” Teela said, as her laugh trailed off into a chuckle, “the mage that designed the window to be a cheerful, talking timepiece, was not entirely precise in his use of magic.”

“Which means?”

“Off the record? Someone tampered with Official Office equipment.”

“This is worse. The old window didn’t greet us by name. What the hells were they trying to do?”

“Get it to shut up without actually breaking it.”

“Which seems to be almost impossible. The breaking-it part.”

“So does the shutting-it-up part, if it comes to that.” Teela grinned. “We’ve started a new betting pool.”

“Hell with the pool—we should just make the Hawklord stay in this damn office. The window would be gone in less than a week.” She started to head toward her very small desk.

“Private Neya,” the window said, “you have not checked today’s duty roster. Please check the roster to ascertain your current rounds.”

Teela burst out laughing because Kaylin’s facial expression could have soured new milk. She did, however, head toward the roster because she couldn’t actually break the window, and she was pretty damn certain it would nag her until she checked.

Elani street had been penciled, in more or less legible writing, beside Kaylin’s name. Severn was her partner. There were no investigations in progress that required her presence, although there were two ongoing. The shift started in half an hour. She took note of it as obviously as possible, and then returned to her desk, by way of Caitlin.

“Good morning, dear,” Caitlin said, looking up from a small and tidy pile of papers.

Kaylin nodded, and then bent slightly over the desk. “What happened to the window?”

The older woman frowned slightly. “We’re not officially certain, dear.” Which meant she wouldn’t say. “Sergeant Kassan is aware that the enchantment on the window is causing some difficulty. I believe he is scheduled to speak with the Hawklord.”

“Thank the gods,” Kaylin replied. The window, during this discussion, was in the process of greeting yet another coworker. “Does it do this all day?”

Caitlin nodded. “You weren’t here yesterday,” she added. Her frown deepened. “It not only greeted the employees by name, it also felt the need to greet every person who walked into—or through—the office in the same way.”

“But—”

Caitlin shrugged. “It’s magic,” she finally said, as if that explained everything. Given how Kaylin generally felt about magic, it probably did.

She tried to decide whether or not to ask about the Imperial Courier. Caitlin was the best source of information in the office, but if she felt it wasn’t important or relevant to the questioner, she gave away exactly nothing. Since she was bound to find out sooner or later—and probably sooner—she held her tongue.

“Private Neya!” The low, deep rumble of Leontine growl momentarily stilled most of the voices in the office. Marcus, as she’d guessed, was not in the best of moods. “Caitlin has work to do, even if you don’t.”

“Sir!” Kaylin replied.

“He’s in the office more than anyone else who works here,” Caitlin whispered, by way of explanation. “And I believe the window likes to have a chat when things are quiet.”

Kaylin grimaced in very real sympathy for Old Ironjaw.

“In particular, I think it’s been trying to give him advice.”

Which meant it wasn’t going to last the week. Thank the gods.

“Oh, and, dear?” Caitlin added, as Kaylin began to move away from her desk, under the watchful glare of her Sergeant.

“Yes?”

“This is for you.” She held out a small sheaf of paper.

Kaylin, who had learned to be allergic to paperwork from a master—that being Marcus himself—cringed reflexively as she held out a hand. “Am I going to like this?”

“Probably not,” Caitlin said with very real sympathy. “I’m afraid it isn’t optional.”

Kaylin looked through the papers in her hands. “This is a class schedule.”

“Yes, dear.”

“But—Mallory’s gone—”

“It’s not about his request that you take—and pass—all of the courses you previously failed, if that’s helpful. The Hawklord vetoed that, although I’m sorry to say Mallory’s suggestion did meet with some departmental approval.”

It was marginally helpful. “What’s it about, then?”

Caitlin winced. “Etiquette lessons. And I believe that Lord Sanabalis has, of course, requested that your magical education resume.”

“Is there any good news?”

“As far as we know, nothing is threatening to destroy either the City or the World, dear.”

Kaylin stared glumly at the missive in her hands. “This is your subtle way of telling me not to start doing either, isn’t it?”

Caitlin smiled. “They’re just lessons. It’s not the end of the World.”

“So,” Severn said, when she joined him and they began to head down the hall, “did you speak with Caitlin?”

“Yes. Let me guess. The entire office already knows the contents of these papers.”

“Betting?”

“No.”

He laughed. “Most of the office. How bad is it?”

“Two days a week with Sanabalis.”

He raised a brow.

“With Lord Sanabalis.”

“Better. Isn’t that the same schedule you were on before the situation in the fiefs? You both survived that.”

“Mostly. I think he broke a few chairs.”

“He’d have to.” Severn grinned. “Gods couldn’t break that table.”

It was true. The table in the West Room—which had been given a much more respectful name before Marcus’s time, which meant Kaylin had no idea what it was—was harder than most sword steel. “Three nights of off-duty time with the etiquette teacher.”

“Nights?”

She nodded grimly.

“Is the teacher someone the Hawks can afford to piss off?”

“I hope so.”

“Who’s teaching?”

“I don’t know. It doesn’t actually say.”

“Where?”

She grimaced. “The Imperial Palace.”

He winced in genuine sympathy. “I’m surprised Lord Grammayre approved this.”

Kaylin was not known for her love of high society. The Hawklord was not known for his desire to have Kaylin and high society anywhere in the same room. Or city block. Which meant the dictate had come from someone superior to the Hawklord.

“It’s not optional,” Kaylin said glumly. “And the worst part is, if I pass, I probably get to do something big. Like meet the Emperor.”

“I’d like to be able to say that won’t kill you.”

“You couldn’t, with a straight face.”

He shrugged. “When do you start?”

“Two days. I meet Sanabalis—Lord Sanabalis—for Magical Studies—”

“Magical Studies? Does it actually say that?”

“Those are the exact words. Don’t look at me, I didn’t write it—in the afternoon tomorrow.” She dropped the schedule into her locker with as much care as she generally dropped dirty towels.

Elani street was not a hub of activity in the morning. It wasn’t exactly deserted, but it was quiet, and the usual consumers of love potions and extracts to combat baldness, impotence, and unwanted weight were lingering on the other side of storefronts. Remembering her mood the last time she’d walked this beat, Kaylin took care not to knock over offending sandwich boards. On the other hand, she also took the same care not to read them.

“Kaylin?”

“Hmm?” She was looking at the cross section of charms in a small case in one window—Mortimer’s Magnificent Magic—and glanced at her partner’s reflection in the glass.

“You’re rubbing your arms.”

She looked down and realized he was right. “They’re sort of itchy,” she said.

He raised one brow. “Sort of itchy?”

The marks that adorned most of the insides of her arms were, like the ones that covered her inner thighs and half of her back, weather vanes for magic. Kaylin hesitated. “It doesn’t feel the way it normally does when there’s strong magic. It’s—they’re just sort of itchy.”

“And they’ve never been like that before.”

She frowned. She’d had fleas once, while cat-sitting for an elderly neighbor. The itch wasn’t quite the same, but it was similar.

She started to tell him as much, and was interrupted midsentence by someone screaming.

It was, as screams went, a joyful, ecstatic sound, which meant their hands fell to their clubs without drawing them. But they—like every other busybody suddenly crowding the streets—turned at the sound of the voice. It was distinctly male, and probably a lot higher than it normally was. Bouncing a glance between each other, they shrugged and headed toward the noise.

The scream slowly gathered enough coherence to form words, and the words, to Kaylin’s surprise, had something to do with hair. And having hair. When they reached the small wagon set up on the street—and Kaylin made a small note to check for permits, as that was one of the Dragon Emperor’s innovations on tax collection—the crowds had formed a thin wall.

The people who lived above the various shops in Elani street had learned, with time and experience, to be enormously cynical. Exposure to every promise of love, hair, or sexual prowess known to man—or woman, for that matter—tended to have that effect, as did the more esoteric promise to tease out the truth about the future and your destined greatness in it. They had pretty much heard—and seen—it all.

And given the charlatans who masqueraded as merchants on much of the street, both the permanent residents and the officers of the Law who patrolled it knew that it wasn’t beyond them to hire an actor to suddenly be miraculously cured of baldness, impotence, or blindness.

Kaylin assumed that the man who was almost crying in joy was one of these actors. But if he was, he was damn good. She started to ask him his name, stopped as he almost hugged her, and then turned to glance at the merchant whose wagon this technically was.

He looked…slack-jawed and surprised. He didn’t even bother to school his expression, which clearly meant he was new to this. Not new to fleecing people, she thought sourly, just new to success. When he took a look at the Hawk that sat dead center on her tabard, he straightened up, and the slack lines of his face tightened into something that might have looked like a grin—on a corpse.

“Officer,” he said, in that loud, booming voice that demanded attention. Or witnesses. “How can I help you on this fine morning?” He had to speak loudly, because the man was continuing his loud, joyful exclamations.

“I’d like to see your permits,” Kaylin replied. She spoke clearly and calmly, but her voice traveled about as far as it would have had she shouted. It was one of the more useful things she’d learned in the Halls of Law. She held out one hand.

“But that’s—that’s outrageous!”

“Take it up with the Emperor,” Kaylin replied, although she did secretly have some sympathy for the man. “Or the merchants’ guild, as they supported it.”

“I am a member in good standing of the guild, and I can assure you—”

She lifted a hand. “It’s not technically illegal for you to claim to be a member in good standing of a guild,” she told him, keeping her voice level, but lowering it slightly. “But if you’re new here, it’s really, really stupid to claim to be a member of the merchants’ guild if you’re not.” Glancing at his wagon, which looked well serviced but definitely aged, she shrugged.

“I am not new to the city,” the man replied. “But I’ve been traveling to far lands in order to bring the citizens of Elantra the finest, the most rare, of mystical unguents and—”

“And you still need a permit to sell them here, or in any of the market streets or their boundaries.” She turned. Lifting her voice, she said, “Okay, people, it’s time to pack it in. Mr.—”

“Stravaganza.”

The things people expected her to be able to repeat with a straight damn face. Kaylin stopped herself from either laughing or snorting. “Mr. Stravaganza is new enough to the City that he’s failed to acquire the proper permits for peddling his wares in the streets. In order to avoid the very heavy fines associated with the lack of permit, he is now closed for business until he makes the journey to the Imperial Tax Offices to acquire said permit.”

Severn, on the other hand, was looking at the bottle he’d casually picked up from the makeshift display. It was small, long, and stoppered. The merchant started to speak, and then stopped the words from falling out of his mouth. “Please, Officer,” he said to Severn. “My gift to a man who defends our city.” He even managed to say this with a more or less straight face.

Severn nodded and carefully pocketed the bottle. As he already had a headful of hair, Kaylin waited while the merchant packed up and started moving down the street. Then she looked at her partner. “What gives?” she said, gesturing toward his pocket.

“I don’t know,” was the unusually serious reply. “But that man wasn’t acting. I’d be willing to bet that he actually thinks the fact that he now has hair is due to the contents of this bottle.”

“You can’t believe that,” she said, voice flat.

Severn shrugged. “Let’s just make sure Mr. Stravaganza crosses the border of our jurisdiction. When he’s S.E.P., we can continue our rounds.”

The wagon made it past the borders and into the realm of Somebody Else’s Problem without further incident. Kaylin and Severn did not, however, make it to the end of their shift in the same way. They corrected their loose pattern of patrol once they returned to the street; as the day had progressed, Elani had become more crowded. This was normal.

Some of the later arrivals were very richly clothed, and came in fine carriages, disembarking with the help of their men; some wore clothing that had been too small a year ago, with patches at elbows and threads of different colors around cuffs and shoulders.

All of them, rich, poor, and shades in between, sought the same things. At a distance, Kaylin saw one carriage stop before the doors of Margot. Margot, with her flame-red hair, her regal and impressive presence, and her damn charisma. Margot’s storefront was, like the woman whose name was plastered in gold leaf across the windows, dramatic and even—Kaylin admitted grudgingly—attractive. It implied wealth, power, and a certain spare style.

To Kaylin, it also heavily implied fraud—but it wasn’t the type of fraud for which the woman could be thrown in jail.

The doors opened and the unknown but obviously well-heeled woman entered the shop. This wasn’t unusual, and at least the woman in question had the money to throw away; far too many of the clientele that frequented Elani street in various shades of desperation didn’t.

Severn gave Kaylin a very pointed look, and she shrugged. “She’s got the money. No one’s going hungry if she throws it away on something stupid.” She started to walk, forcing Severn to fall in beside her. Her own feelings about most of Elani’s less genuine merchants were well-known.

She slowed, and after a moment she added, “I know there are worse things, Severn. I’m trying.”

His silence was a comfortable silence; she fit into it, and he let her. But they hadn’t reached the corner before they heard shouting, and they glanced once at each other before turning on their heels and heading back down the street.

The well-dressed woman who had entered Margot’s was in the process of leaving it in high, high dudgeon. Margot was—even at this distance—an unusual shade of pale that almost looked bad with her hair. Kaylin tried not to let the momentary pettiness of satisfaction distract her, and failed miserably; Margot was demonstrably still healthy, her store was still in one piece, and at this distance it didn’t appear that any Imperial Laws had been broken.

“Please, Lady,” Margot was saying. “I assure you—”

“I am done with your assurances, Margot,” was the icy reply. The woman turned, caught sight of the Hawks, and drew herself to her full height. “Officers,” she said coldly. “I demand that you arrest this—this woman—for slander.”

“While we would dearly love to arrest this woman in the course of our duties,” Kaylin said carefully, “most of what she says is confined to private meetings. Nor is what she says to her clients maliciously—or at least publicly—spread.”

“No?” The woman still spoke as if winter were language. “She spoke—in public—”

“I spoke in private,” Margot said quickly. “In the confines of my own establishment—”

“You spoke in front of your other clients,” the woman snapped. “When my father hears of this, you will be finished here, do you understand? You will be languishing in the Imperial jail!”

It was too much to hope that she would climb the steps to the open door of her carriage and leave. She turned once again to Kaylin; Severn was, as usual, enjoying the advantage of having kept his mouth shut. It was a neat trick, and Kaylin wished—for the thousandth time—that she could learn it. Or, rather, had already learned it.

“You will arrest this—this charlatan immediately.”

“Ma’am, we need to have something to arrest her for.”

“I’ve already told you—”

“You haven’t told us what she said,” Kaylin replied. Given the heightening of color across the woman’s cheeks, the fact that this was required seemed to further enrage her.

“Do you know who I am?”

It was the kind of question that Kaylin most hated, and it was the chief reason that her duties were not supposed to take her anywhere where it could, with such genuine outrage, be asked. “No, ma’am, I’m afraid I haven’t had the privilege.”

Her eyes rounded, and out of the corner of her eye, Kaylin saw that Margot was wincing.

“Who, may I ask, are you?” the woman now said.

“Private Neya, of the Hawks.”

“And you are somehow supposed to be responsible for safeguarding the people of this fair city when you clearly fail to recognize something as significant as the crest upon this carriage?”

Kaylin opened her mouth to reply, but a reply was clearly no longer desired—or acceptable.

“Very well, Private. I will speak with Lord Grammayre myself.” She spoke very clear, pointed High Barrani to her driver, and then stomped her way up the step and into the carriage. Had she been responsible for closing its door herself, it would have probably shattered. As it was, the footman did a much more careful job.

They watched the carriage drive away.

“I suppose there’s not much chance that she’s just going to go home and stew?” she asked Severn.

“No.”

“Is she important enough to gain immediate audience with the Hawklord?”

Margot sputtered before Severn could answer, but that was fine. Severn’s expression was pretty damn clear. “She is Lady Alyssa of the Larienne family. Did you truly not recognize her?”

Larienne. Larienne. Like most of the wealthy families in Elantra, they sported a mock-Barrani name. Something about it was familiar. “Go on.”

“Her father is Garavan Larienne, the head of the family. He is also the Chancellor of the Exchequer.”

Kaylin turned to Severn. “How bad is it going to be?”

“Oh, probably a few inches of paper on Marcus’s desk.”

She wilted. “All right, Margot. Since I’m going to be on report in a matter of hours—”

“Hour,” Severn said quietly.

“What the hell did you say that offended her so badly?”

“I’d prefer not to repeat it.”

Kaylin sourly told her what she could do with her preferences.

“So let me get this straight. Lady Alyssa comes to you for advice about her love life—”

“She is Garavan’s only daughter.” Margot was now subdued. She was still off her color. “And she’s been a client for only a few months. She is, of course, concerned with her greater destiny.”

“I’m not. What I’m concerned with is the statement Corporal Handred has taken from some of your other clients. You told Lady Alyssa that her father was going to be charged with embezzlement, and the family fortunes would be in steep decline? You?”

Margot opened her mouth, and nothing fell out of it. Kaylin had often daydreamed about Margot at a loss for words; this wasn’t exactly how she’d hoped it would come about.

“I—” Margot shook her head. “I had no intention of saying any such thing, Her father’s business is not her business, and she doesn’t ask about him.”

“Then what in the hells possessed you to do it now?”

“She—she sat in her normal chair, and she asked me if—if I had any further insight into her particular situation.”

“And that was your answer? Come on, Margot. You’ve been running this place—successfully—for too damn many years to just open your mouth and offend someone you consider important.”

“That was my answer,” was the stiff reply. “I felt—strange, Private. I felt as if—I could see what would happen. As if it were unfolding before my eyes. I didn’t mean to speak the words. The words just came.” She spoke very softly, even given the lack of actual customers in her storefront; she had sent them, quietly, on their way. Apparently, whatever it was that was coming out of her mouth was not to be trusted, and she was willing to lose a full day’s worth of income to make sure it didn’t happen again.

“So. A cure for baldness that worked—instantly—and a fortune-teller’s trick that might also be genuine.”

“I’d keep that last to yourself.”

She shrugged. “I think it’s time we visited all of the damn shops on Elani, door-to-door, and had a little talk with the proprietors.”

Severn, who didn’t dislike Margot as much as Kaylin, had been both less amused at her predicament and less amused by the two incidents than Kaylin. Kaylin let her brain catch up with her sense of humor, and the grin slowly faded from her face, as well. “Come on,” she told him.

“Where are we starting?”

“Evanton’s. If we’re lucky, that’ll take up the remainder of the shift, and then some. I’m not looking forward to signing out tonight.”

CHAPTER 2

Evanton’s apprentice, Grethan, opened the door before Kaylin managed to touch it. He looked as if he hadn’t slept in three days, and judging from his expression, Kaylin and Severn were part of his waking nightmare.

“Are you shutting up for the day?” Kaylin asked, keeping her voice quiet and low.

He looked confused, and then shook himself. “No,” he told her. “I was just—going out. For a walk,” he added quickly.

She didn’t ask him how Evanton was; he’d pretty much already answered that question. But she did walk into the cluttered, gloomy front room, and she stopped as she crested the opening between two cases of shelving. The light here was brilliant.

Evanton was wearing his usual apron, and it was decorated with the usual pins and escapee threads of the variety of materials with which he worked. But his eyes were, like the lights in the room, a little too bright. He glanced at her, his hands pulling thread through a thick, dark fabric that lay in a drape across his spindly lap. “I was wondering,” he said, although it was somewhat muffled, given the pins between his lips, “when you would show up.”

“The Garden—”

“Oh, the Garden’s fine. Whatever you did in the fiefs a couple of weeks ago was enough to calm it. It looks normal. No, the Garden is not your problem.” He removed the pins and stuck them carefully into one of a half-dozen oddly shaped pincushions by his left arm. “I’ve almost finished with your cloak,” he added, “if you want to try it on.”

She had the grace to redden. “Not now,” she told him. “I’m on duty.”

He raised a brow. “Have you two been on patrol all morning?”

Kaylin nodded.

“Notice anything unusual?”

She nodded again, but this time more slowly. Note to self: visit Evanton’s first, next time you’re in Elani. “What is it, Evanton? We’re just about to make a sweep of the street to see if anything else unusual turns up.”

“I hope you’ve got a lot of time,” the old man replied. He rose and folded the cloth in his lap into a careful bundle. “I’d offer you tea, but the boy’s forgotten to fill the bucket.”

“I can fill it—”

“No. That won’t be necessary.”

She frowned.

“It’s not only in the rest of the street that the unusual is occurring,” he told her. “This morning, when he came in with the water, the water started to speak to him.”

“Evanton—”

“Yes. He was born deaf, by the standards of the Tha’alani. He has always been mind deaf, but he is still Tha’alani by birth. In the Elemental Garden, he can hear the water’s voice, and through it, some echo of the voice of his people. This is the first time it’s happened outside of the Garden, and the water was in buckets. It is not, sadly, still in those buckets. I can’t get him to drink a glass of water at the moment. He sits and stares at it instead.” He frowned. “I had heard rumors that you were studying magic with Lord Sanabalis.”

“From who?”

“Private, please. I gather from your sour expression that the rumors are true. You might wish to speak with Lord Sanabalis about the events on Elani at your earliest convenience. If we are lucky, he will be unaware of the difficulties you might encounter.”

“And if we’re not?”

“He will already know, and it will mean that the difficulties are present across a much wider area of the city.”

“What will it mean to him?”

“What it should mean to you, if you’ve been studying for any length of time,” was the curt reply. But Evanton did relent. “There has been a significant and sudden shift in the magical potential of an area that is at least as broad as Elani.”

Kaylin froze. “Severn, are you thinking what I’m thinking?”

“I’m thinking that our sample size—of three—is more than enough for the day. We should return to the office immediately.”

Evanton frowned, although with his face it was sometimes difficult to tell. “Something unusual happened outside of the confines of this particular neighborhood.”

“Yes. An enchantment laid against some of the windows in the Halls of Law has developed a more commanding and distinct personality than it possessed a few days ago.”

Evanton closed his eyes. “Go, Private, Corporal. Speak with the Hawklord now.”

Speaking with the Hawklord was not at the top of Kaylin’s list of things to do before the end of her shift. Or at all. He was—they all were—aware of the shortcomings in an education that didn’t include the rich and the powerful on this side of the Ablayne. For one, power in the fiefs usually meant brute force; manners were what you developed when you wanted to avoid pissing off the brute force in question. Marcus had once told her that manners in the rest of Elantra were exactly the same thing, but Kaylin knew they weren’t. In the fiefs, the best manners were often either silence or total invisibility.

Here, you were actually expected to talk and interact. Without obvious groveling or fawning, and without obvious fear.

Severn caught her hand.

“What?”

“Stop rubbing your arm like that. You’ll take your skin off.”

“Like that would be a bad thing.” But she did stop. “I should have known,” she added. “You suspected?”

“I wondered.”

The Halls loomed in a distance that was growing shorter as they walked; they weren’t patrolling, so there was no need for a leisurely pace. They also weren’t running because running Hawks made people nervous.

Tanner took one look at her face and stepped to one side. “Trouble?” he asked them both.

“Possible trouble,” Kaylin replied. They breezed through the Aerie and the halls that led to the office that was Kaylin’s second home. Marcus was at his desk, and he roared when he caught sight of them. Kaylin cringed.

“Here. Now.”

Only a suicidal idiot would have ignored that tone of voice. Or the claws that were adding new runnels to scant clear desk surface. Both she and Severn made their way to the safe side of his desk—the one he wasn’t on. Kaylin lifted her chin, exposing her throat. Marcus actually glowered at it as if he was considering his options; his eyes were a very deep orange, and about as far from his usual golden color as they could get when death wasn’t involved.

“In your rounds in Elani today did you happen to encounter anyone significant?” he growled, his voice on the lower end of the Leontine scale. The office had fallen—mostly—silent; total silence would probably occur only in the event of the deaths of everyone in it.

“Alyssa Larienne.”

“Lady Alyssa Larienne. She is the daughter of one of the oldest—and wealthiest—human families in Elantra. Her father is a member of significance in the human Caste Court. Her mother is the daughter of the castelord. If you wanted to make my life more difficult when dealing with the human Caste Court, you couldn’t have chosen a better person to offend.”

Well, there is her father. This time, Kaylin kept her mouth shut.

“I expect there to be a good explanation for this.”

“I wasn’t the one who actually offended her, if that helps.”

He snarled, which meant it didn’t. “What happened?”

“She’s a client of Margot’s.”

“You’re telling me—with a straight face and your job on the line—that Margot offended her.”

“Yes, sir.”

“How?”

“That’s part of why we’re here—”

“Stick with this part, for now. Report on the rest later.”

“Yes, sir.” She took a deep breath. “Lady Alyssa arrived for her usual appointment. Today, Margot chose to tell her that her father, Garavan Larienne, was to be arrested for embezzlement.”

Breathing would have made more noise than the combined contents of the office now did.

“Let me get this straight. Margot told Alyssa Larienne that the Chancellor of the Exchequer was to be arraigned for embezzlement.”

“Yes, sir.”

“And your part in this was?”

“Lady Alyssa demanded that I arrest Margot for slander. I personally would love to arrest Margot for anything she could possibly—”

Marcus flexed his claws. Kaylin took this as a sign that she should answer his questions, and only his questions. “I asked Lady Alyssa what Margot had said. She declined to repeat it. She did not decline to repeat her demand.”

Marcus’s eyes were still orange.

“She did, however, take offense at the idea that I didn’t immediately recognize the crest on her carriage or her own import, since obviously either of those would lead me to arrest Margot on the spot, and said she would take it up with Lord Grammayre personally.”

Marcus growled. “This is extremely unfortunate. I would like you to request that Margot come into the office for debriefing.”

Kaylin’s jaw nearly dropped. “What?”

“Which part of that sentence wasn’t clear?”

Severn cleared his throat. “When would you like us to request Margot’s cooperation with the Halls of Law?”

“After you finish speaking with Lord Grammayre. You’re early,” he added, his eyes narrowing. “Please tell me there is no other emergency in Elani.” Oddly enough, when he said this, his eyes began to shade into a more acceptable bronze.

Severn was notably silent.

“It would save me paperwork and ulcers if I just chained you to a desk, Private. Go talk to the Hawklord. Now.”

“Private,” Kaylin whispered, as they walked quickly up the spiral staircase. “As if you weren’t there at all.”

“You seem to be fairly good at attracting trouble in spite of your assigned partner,” Severn replied, with a faint smile.

“If Margot has somehow blown things for an ongoing investigation…” She didn’t finish, because they reached the Hawklord’s tower door. They’d bypassed his office, but Kaylin didn’t expect him to be in his office; he rarely conducted his meetings there. For one, it was as crowded and cluttered as any busy person’s office. It also wasn’t as imposing as the more austere and architecturally impressive tower itself.

“This,” Kaylin muttered, as Severn placed his palm firmly across the doorward of the closed tower doors, “is worse than magic. This is politics.”

“On the bright side,” Severn replied, as the door swung inward, “this is probably making etiquette lessons look a lot more inviting.”

The Hawklord was standing in front of his perfect, oval mirror. In and of itself, this was not a bad sign. The mirror, however, reflected no part of the room, which meant he was accessing Records. Kaylin could see nothing but a blank, black surface. He glanced over his shoulder as she and Severn walked into the room, and she stopped almost immediately.

His eyes were blue.

Blue, in the Aerians, like blue in the Barrani, was not a good sign. With luck, it meant anger. With less luck, it meant fury. In either case, it meant tread carefully. Likewise, the Hawklord’s wings were high above his shoulders. They weren’t fully extended; they were loosely gathered. She’d seen loosely gathered Aerian wings strike and break bone exactly once.

She offered the Hawklord a perfect salute. Severn, by her side, did likewise.

“Alyssa Larienne came to this tower just over an hour ago,” he said without preamble. “Sergeant Kassan attempted to detain her by taking a detailed report of the incident which had angered her.”

Kaylin winced.

“As a result she left the Halls some fifteen minutes before your arrival.” The Hawklord’s wings twitched. His eyes were still a very glacial blue. “She did not appreciate the filing of an incident report. I was assured that Sergeant Kassan was polite and respectful.”

“She probably doesn’t have much to do with Leontines on a daily basis,” Kaylin pointed out. “She might not have been able to tell.”

“That,” the Hawklord said, and he did grimace, “is my profound hope. What happened in Elani street, Private Neya?”

Kaylin stared straight ahead. She wanted to at least look at Severn, because she could read minute changes in his expression well enough to be guided by them. But in the Hawklord’s current mood that might be career-limiting.

“We’re not entirely sure, sir. We cut our patrol short to report,” she told Lord Grammayre. “After we visited Evanton.”

The Hawklord’s face became about as inviting and open as the stone walls that enclosed them. “Continue.”

“There were three incidents in the space of a few hours of which we’re aware. With your permission, we’ll canvass the merchants and residents of the street tomorrow to see how many others we missed.”

“Incidents?”

She hesitated; he marked it. But he waited. “The first was a man selling a cure for baldness that actually appeared to work—instantly.”

He raised one pale brow. “It is Elani street.”

“Sir.” This time she did glance at Severn; his chin dipped slightly down. “We took the merchant’s name. Corporal Handred acquired a sample of the tonic.”

“You…believe that this was genuine.”

“Much as I hate to admit it, yes.”

“Go on.”

“The second incident of note, you’ve already heard about. Alyssa Larienne.”

“Lady Alyssa Larienne is young, idealistic, and convinced of her own importance.”

Severn cleared his throat.

“Corporal?”

“I would say that she is young, insecure, and in need of someone to convince her of that import.”

“She throws her weight around—” Kaylin broke in.

“If she was certain she had that weight, she wouldn’t need to throw it.”

Kaylin shrugged. “For whatever reason, she’s been a client of Margot’s for many months.”

“Margot Hemming?”

“The same.”

“Margot Hemming is not, to my knowledge, and to the knowledge of Imperial Records, a mage. She has no training, and no notable talent or skill. She is, by human standards, striking. She is forty years of age—”

“She can’t be forty.”

“She is forty years of age,” he repeated, spacing the words out thinly and evenly. “And she has twice been charged with fraud in the last twenty-five. She is not violent, she has no great pretensions, and for the last decade, she has settled into the life of a woman of modest, respectable means.”

Kaylin glanced at the flat surface of a mirror that reflected nothing, and the Hawklord continued. “She has no known criminal ties, she is despised by the merchants’ guild, she donates money to the Foundling Halls.”

Kaylin’s brows disappeared into her hairline. “She what?”

“She can afford it.”

“That’s not the point.”

“No. It is not. She has very few clients of any significant political standing. Garavan Larienne does not travel to her shop, nor does his wife. She supports no political causes that we are aware of, and believe that I have demanded every possible legal record that she might be associated with, however distantly. But she has, today, single-handedly caused the Hawks—and the Swords, and possibly indirectly, the Wolves—more difficulty than the Arcanum has in its entire history.”

Kaylin closed her eyes.

“What did Margot Hemming do, Private?”

“She told a fortune, more or less.”

“I am aware of the fortune’s contents.” He turned. “The other difficulties?”

“After the incident with Margot, we paid a visit to Evanton’s. Evanton said that…there was an incident in the store, involving his apprentice.”

“Did it also involve the future of arguably the most politically powerful human in Elantra?”

“No, sir.”

“Then I am not interested in the details at this present moment. Continue.”

“It was also of a magical nature. Evanton thinks—thought—that there is an unusually strong flux in the magical potential of a specific area, and it’s causing things to go completely out of whack.”

“His words?”

“Not exactly.”

“What, exactly, were his words?”

“He thought I should speak with Sanabalis—”

“Lord Sanabalis.”

“Lord Sanabalis. Now.”

“Far be it from me to ignore the urgent advice of so important a man,” the Hawklord replied.

“He thinks it could be disastrous if we don’t—”

“It has already been almost disastrous. At this particular moment in my career, I fail to see how it could be worse. Take Corporal Handred with you, avoid any discussion of Larienne, and avoid, as well, any men who obviously bear his colors. Go directly to Lord Sanabalis, make your report, and return directly here. If I am absent, wait.”

“Sir.”

The Imperial Palace, home of future etiquette lessons, loomed in the distance of carriage windows like the cages outside of Castle Nightshade. The flags were, as they almost always were, at full height, and the wind at that height was impressive today; it buffeted clouds.

Severn, seated across from Kaylin, glanced at her arms. It wasn’t a pointed glance, but she rolled back one sleeve, exposing the heavy, golden bracer that bracketed her wrist. The unnatural gems, socketed in a line down its length, gleamed in the darkened interior of the carriage. He nodded, and she rolled her sleeve down, covering it. By Imperial Edict, and by the Hawklord’s command—which were in theory the same thing—she wore it all the time.

It prevented the unpredictable magic she could sometimes use from bubbling to the surface in disastrous ways. It unfortunately also prevented the more predictable—to Kaylin—magic that was actually helpful from being used, so it didn’t always reside on her wrist, edict notwithstanding. Her magic could be used to heal the injured, and it was most often used when the midwives called her in on emergencies.

But it was this wild magic, and the unpredictable and unknown nature of it, that was at the root of the Magical Studies classes she was taking with Sanabalis. The Imperial Court reasoned that if she could use and channel magic like actual working mages did, she would be in control of it. And, in theory, the Court would be in control of her, because indirectly they paid her salary, and she liked to eat.

It was also the magic that was at the heart of etiquette lessons. The Dragon Emperor was not famed for his tolerance and sense of humor. He was, in fact, known for his lack of both. But Sanabalis, Tiamaris, and even the ancient Arkon who guarded the Imperial Library as if it was his personal hoard—largely because it was—all felt that she would soon have to come to Court and spend time in the presence of the Dragon who ruled them all. They wanted her to survive it, although Sanabalis on some days seemed less certain.

The carriage rolled to a halt in the usual courtyard. It was not an Imperial Carriage; most Hawks who didn’t have Lord somewhere in their name didn’t have regular use of those. It did bear the Hawk symbol, and a smaller version of the Imperial Crest, but it also needed both paint and a good, solid week’s worth of scrubbing.

Still, it did the job. The men who always stood in the courtyard opened the side doors, but they didn’t offer her either the small step that seemed to come with most fancy carriages, or help getting out of the seat that was so damn uncomfortable on long, bumpy rides. They just opened the door, peered briefly in, and got out of the way.

She handed one of them the letter Caitlin had written. Marcus had signed it with a characteristic bold paw print under a signature that was—if you knew Leontines—mostly legible. Caitlin, on the other hand, had done the sealing. Marcus didn’t care for wax.

He hadn’t much cared for her destination, either, but only barely threatened to rip out her throat if she embarrassed the department, which was bad; it meant he had other things on his mind. His eyes had never once shaded back to their familiar gold.

The man who had taken the sealed letter returned about fifteen minutes later, accompanied by a man she recognized, although not by name.

“Lord Sanabalis,” this man said, with a stiff bow, “will see you. Please follow me.”

She started to tell him she knew the way, and bit her tongue.

Sure enough, she did know the way, because he took her to Sanabalis’s personal meeting room. It wasn’t an office; there was no sign of a desk, or anything that looked remotely business-like—besides the Dragon Lord himself—in the room. And it had windows that did not, in fact, give out lectures on decorum, dress, and the use of racially correct language to random passersby. The windows here, on the other hand, were impressive, beveled glass that looked out on one of the best views of the Halls of Law in the city.

“If this,” he told Kaylin, indicating one of the many chairs positioned in front of the one he occupied, “is about your class schedule, I will be tempted to reduce you to ash on the spot.” As his eyes were the familiar gold that Marcus’s hadn’t been since she’d returned to the office, she assumed this was what passed for Dragon humor, and she took a chair.

Severn did likewise.

“It’s not about the class schedule, although if you want my opinion—”

Sanabalis raised a pale, finely veined hand. It looked like an older man’s hand, but it could, in a pinch, probably drive a dent into solid rock. Dragons could look like aged wise men, but it was only ever cosmetic. They were immortal, like the Barrani. They lacked Barrani magnetism, and their unearthly beauty and grace, but Kaylin assumed that was because they didn’t actually care what the Barrani or the merely mortal thought of them. At all.

“I believe, given previous exposure to your opinions, I can derive it from first principles.”

Severn coughed. Kaylin glared at the side of his face, because for Severn, this was laughter that he’d only barely managed to contain. “There was an incident in Elani street today.”

So much for gold. His eyes started the shade-shift into bronze the minute she mentioned the street. “I take it,” she added, “you heard.”

“We were informed—immediately—by Lord Grammayre, yes. I am not at liberty to discuss it at the moment. I am barely at liberty to have this meeting,” he added. “But in general, you come to the Palace with information that is relevant, and often urgent. Do not, however, waste my time.”

“I didn’t cause the incident. I caused outrage because I didn’t immediately obey the orders of a pissed-off noble.”

“Understood. You have information on what did cause the incident?”

“Not directly.”

He snorted. Small plumes of smoke left his nostrils, which was unusual. “Evanton sent me,” she said quickly.

“The Keeper sent you?”

She nodded. “He started to talk about magical potential, and the sudden surge he felt in Elani.”

Sanabalis was silent. It wasn’t a good silence.

“He—the incident with Alyssa Larienne—he thought the magical potential shift was responsible for it somehow.”

“Let me reverse my earlier position,” he said quietly. “What were the other incidents?”

She told him.

His eyes were now the color of new copper. “And these incidents,” he finally said, rising and turning his face toward the window. “Did they all occur within roughly the same area?”

It was Severn who answered. “We aren’t entirely certain of that.”

“How uncertain are you, and why?”

“You are no doubt aware that Sergeant Mallory made a few changes to the official office out of which the Hawks operate. One of those changes was—”

“The window, yes. I can tell you his requisition raised a few eyebrows in the Order.”

“The window is perhaps not the most popular addition to the office. It is, however, impervious to most casual attempts to harm it.”

“Go on.”

“Someone attempted to dampen or neutralize the magic on the window—or so we believed.”

“Tampering with official property?”

“As I said, that was our belief at the time. Given the nature of the enchantment—”

“It would be entirely believable. What happened?”

“The window now greets visitors—and staff—by name. Among other things. Its lectures have become more directed.”

“The names could possibly have been carried over from any connection with Records, and I assume, given the requisition request, that connection would be mandatory.”

“That was the theory. The window began, however, to greet visitors by name, as well, and some of those visitors don’t exist in our Records. None of the Hawks are mages. We naturally assumed, given the nature of the original enchantment, that the attempt to disenchant the window had simply skewed it.”

Sanabalis raised a hand, not to silence Severn, but to touch the window that separated them from high, open sky. Kaylin’s hair began to stand on end.

The window darkened instantly, shutting out both sunlight and the sight of the Halls of Law. The bars that separated the panes seemed to melt into the surface of what had once been glass until the entire bay looked like a smooth, featureless trifold wall.

“Records,” Sanabalis said, and the blackness rippled at the force of the single word. So, Kaylin swore, did the ground. He was using his dragon voice. The mirror—such as it was—rippled again, and this time light coalesced in streaks of horizontal lines. Sanabalis inhaled. Kaylin lifted her hands to cover her ears. Severn caught them both in his and pulled them down as the dragon spit out a phrase that Kaylin could literally feel pass through her.

“When you finally get called to Court,” Severn told her, when it was silent again, “you won’t be able to do that. Not more than once.”

“They’ll…” She grimaced. “I just assumed they’d be speaking High Barrani.” She swallowed, nodded, and wondered how bad a Court meeting would be if she couldn’t actually hear anything after the first few sentences.

Severn released her hands; they both turned to face the image that Sanabalis had called so uncomfortably into being. It was, to Kaylin’s surprise, a map. “We,” the Dragon Lord said, without looking away from the lines that now stretched, in different shades, and in different widths, across the entire surface area, “are here.” A building seemed to dredge itself out of the network of lines, assuming solid shape and texture; it was, however, small.

“The Halls, as you can see, are here.” A miniature version of the Halls also seemed to grow out of the surface of the map.

“The Keeper’s responsibility is here.” He gestured, and a third building rose out of the map. Kaylin frowned as it did. She walked past Evanton’s shop at least a dozen times a day when she was sent to Elani on patrol. That shop and the one that now emerged at Sanabalis’s unspoken command had nothing in common.

“Private, is there some difficulty?”

She turned to Severn. “Severn, does that look like Evanton’s place to you?”

“No.”

Sanabalis frowned. “It is a representation of—” The frown deepened, cutting off the rest of his words. His eyes narrowed and he leaned toward the emerging building. He needn’t have bothered; the building that had started out in miniature began to expand, uprooting the lines that were meant to represent streets or rivers as if they were dusty webs.

The dragon spoke, loudly, at the image. It froze in place.

“It appears,” he said softly—or at least softly compared to his previous words—“that we have a serious problem.”

CHAPTER 3

When a Dragon of Sanabalis’s power uses the word problem in that tone of voice, you start to look for two things: a good weapon, and a place to hide, because, when it comes right down to it, the weapon’s going to be useless. Kaylin, aware of this, did neither.

“Problem?” she said, staring at the malformed map. Sanabalis didn’t appear to have heard her. Clearing her throat, she said, “What are the distances from the Palace to the Halls, the Halls to Elani and the Palace to Elani?”

“I would prefer, at this point, not to ask,” he replied. “Suffice it to say it is not an insignificant distance. The full length of Elani itself would not have been an insignificant distance, given the perturbations you’ve described. I am now assuming that either Margot or the young Alyssa Larienne drew upon the waiting potential and used it. That they did so entirely without intent…

“Come,” he told them both, and turned away from the mirror.

“Where are we going?”

“You are going to the courtyard. I will meet you there with an Imperial Carriage.”

“Why?”

“I would prefer not to use magic at this point. I would also prefer to have no one else use it. Word of this zone, if we can even deduce its boundaries, will spread. We cannot afford to have it touched or used by the wrong people.”

Kaylin stilled. “People can deliberately use it?”

“Not without effort, and not without unpredictable results. Mages are likely to find their spells much more powerful in that zone, and if they are not prepared for it and they are using the wrong spells, it could prove fatal. It is not, however, for the mages that I am concerned.”

“This has happened before,” she said, voice flat.

“Yes, of course it has. Magic is not easily caged or defined. It has not, however, happened over an area this large in any recent history.”

“How recent is recent?”

“The existence of our current Empire.”

Immortals.

If Kaylin had any curiosity about where Sanabalis had gone in the brief interval before he met them in the courtyard, it was satisfied before they left the Palace: she could hear the thunderous clap of syllables that was the equivalent of dragon shouting. The Imperial guards, to give them their due, didn’t even blink as she and Severn walked past.

But if Dragons were immortal, an emergency was still an emergency; they waited for maybe fifteen minutes in total before Sanabalis, looking composed and grim, met them. “Do not,” he said, although Kaylin hadn’t even opened her mouth, “ask.” He glared at the carriage door, and it opened, although admittedly it opened at the hands of footmen.

The ride was grim, silent, and fast. Imperial Carriages were built for as much comfort as a carriage allowed, and people got out of its way. Sanabalis had the door open when it hit the Halls’ yard; the Halls, unlike the Palace, expected people to more or less do things for themselves. He waited until the precise moment someone else had a hand on the horse’s jesses, and then jumped down. Kaylin and Severn did the same, following him as quickly as they could without breaking into a run.

Sanabalis wasn’t running, of course.

There was what wouldn’t pass for a cursory inspection at the front doors; Sanabalis gave his name, but the formality of crossed polearms failed to happen because Sanabalis also didn’t stop moving. They didn’t have time to send a runner ahead, at least not on foot, but there were Aerians practicing maneuvers in the Aerie that opened up just behind the front doors, and Kaylin noticed the way at least one shadow dropped out of formation.

Lord Grammayre was, uncharacteristically, not in his Tower when they finally crested the last corner and hit the office proper. Nor was Marcus behind his desk. The two of them were standing more or less in the space in front of Caitlin’s desk, which was what passed for a reception area this deep into the Halls itself. They turned to greet Sanabalis as he walked briskly toward them.

“Lord Sanabalis,” the Hawklord said, bowing.

“Lord Grammayre. I have need of your Hawks.”

“Of course.”

“Let us repair to the West Room. We can discuss the nature of their deployment—and their new schedule.”

Marcus didn’t even blink.

“For reasons which will become clear, I would like to shut down the use of Records except in emergencies.” He turned to the small mirror on the wall. “Records,” he said. Which would clearly make this an emergency.

Lord Grammayre lifted his left wing, and then nodded.

“I have spoken with the Imperial Order of mages. The Emperor is currently evaluating the possibility of a quarantine on the Arcanum. Map, Elantra.”

A map that was in no way the equal of the one he’d called on in the Palace shimmered into view. For one, it occupied a much smaller surface. Reaching out, Sanabalis touched three points on the map; they were familiar to Kaylin.

“A quarantine?” the Hawklord asked, watching the map shift colors where the Dragon Lord had touched it.

Sanabalis nodded grimly. “I will,” he added, “speak with the Lord of Swords when I am finished here. If it is possible, it will be his duty to see that it is enforced.”

“That is not likely to make the Emperor more popular with the Arcanists.”

“Nothing short of his disappearance would do that. The Arcanists are a concern, but they are not the cause of the current difficulty. They are merely the most obvious avenue for turning it into a disaster. Here,” he added. “Here, and here. At the moment, they are sites in which what I will call leakage for the purpose of discussion has been known to occur. The leakage in your office—the windows—is not as severe as the incidents that occurred in Elani street.

“It does not, however, matter. People’s expectations during this unfortunate leakage guide some of its effects. Our historical Records are, as might be expected, veiled. The Arkon is looking over them now.”

“Are there historical Records that would be relevant, Lord Sanabalis?”

“There are. They are not exactly fonts of optimism, however. What we need the Hawks to do is, as Private Neya would colloquially put it, ‘hit the streets.’ We need to ascertain what the boundaries of the area are. Look for the unusual. Look for the miraculous. Take note of the usual crimes or deaths, but examine them for any…unexplained…phenomenon. This has to start now,” he added.

“The Emperor himself will speak to the Master Arcanist. He has been summoned to Court as a precaution. At the moment however, the Arcanum sits squarely outside of the area marked by the three geographical incidents. With luck, it will remain that way.

“Sergeant Kassan,” Sanabalis added, “you may assure your Hawks that they will be adequately reimbursed for their extra duties.”

Marcus looked as though he had just swallowed something more unpleasant than a week’s worth of unforwarded reports. “Several of the Hawks are involved in the current investigation into the Exchequer.”

“It pains me to say this, Sergeant Kassan, but both duties—the more subtle and now-endangered investigation, and the much less predictable magical one—must be fully discharged.

“As Private Neya is not currently involved in the former, I suggest you deploy her in the latter. I have taken the liberty of arranging an appointment with the Oracular Halls, as she had some success in not offending the man who runs it on her previous visit. I would recommend that you send both her and her current partner.”

“I have—” Kaylin began.

“Private Neya will, however, be excused her classes.”

Kaylin shut her mouth.

“Or rather,” Sanabalis continued, “her classes under my tutelage. I was unable to shift the class schedule for the etiquette lessons, and it is vital that she not offend that teacher.” He turned to Kaylin. “If anything is untoward or of particular interest in the Oracular Halls, you will return to the Palace to report to me.”

Kaylin glanced at Marcus, who nodded stiffly, and managed not to growl. Given the state of his hair, much of which was standing on end, it was surprising. In a good way.

As if he could read that stray thought, the Sergeant added, “And you’ll report back at the Halls after you’ve been debriefed at the Palace.”

“But—”

“I don’t care how late it is. From the sounds of it, the office will be operating under extended hours.” He grimaced, which in Leontine involved more fur and ears than actual facial expression. “I’ll mirror my wives and let them know.”

She didn’t envy him that call.

The appointment with the Oracular Halls was, ironically enough, one hour in the future. Sanabalis handed Kaylin a very official document with the unmistakable seal of the Eternal Emperor occupying the lower left quarter, where words weren’t.

“Take the Imperial Carriage. Master Sabrai will be expecting you,” he told her. “He did not, of course, have time to respond to or question the request, and he did not look terribly surprised to receive it, which is telling.”

What it told Sanabalis, Kaylin wasn’t sure; Sabrai was an oracle, after all, and they were supposed to be able to thresh glimpses of the future out of the broken dreams and visions of the Halls’ many occupants. “What am I supposed to discuss as the official representative of the Imperial Court?”

“I’m sure you’ll think of something. Given the lack of disaster during your last visit—in spite of your many attempts to contravene the rules for visitors to the Halls—I am willing to trust your discretion in this matter.”

Someone cursed, loudly, in Leontine. Kaylin recognized the voice: it was Teela’s.

“Well,” she told Sanabalis, “Severn and I will head there immediately.” She managed to make it out of the office as other voices, mostly Barrani, joined Teela’s. Marcus had apparently already started the who-hates-the-duty-roster-most game, and while the Barrani in the office were Hawks first, they were still Barrani. Barrani in a foul mood were a very special version of Hell, which, if you were lucky, you survived intact.

Given the way the day had started, she didn’t feel particularly lucky.

“It isn’t cowardice,” Severn said, with a wry grin, because he understood her sudden desire for punctuality. “It’s common sense.”

The Oracular Halls, as befitted any mystical institution that labored in service to the Eternal Emperor, was imposing. Constructed of stone in various layers that suggested a very sharp cliff face, it was surrounded on all sides by a fence that looked as if it would impale any careless bird that landed on it. The posts were grounded by about three feet of stone that was at least as solid as the walls it protected; it wasn’t going to be blown over by a storm, a mage, or an angry Leontine.

A Dragon, on the other hand, wouldn’t have too much trouble.

In the center of the east side of the fence, which fronted the wide streets that led up to and around it, was a guardhouse. It was late in the day, but the hour did not lead to less guards; there seemed to be more than the last time she’d visited at the side of Lord Sanabalis. She counted eight visible men, and those eight wore expensive, very heavy armor. They also carried swords.

Severn glanced at her as the carriage came to a halt, but said nothing.

The guards didn’t meet the carriage itself; they waited until it disgorged its occupants. Said occupants walked—in much less heavy armor—to the wide, very closed, doors that led to the grounds. To Kaylin’s surprise, the guards didn’t demand her name or her business. Then again, the first thing she did was hand them the paper that Sanabalis had handed her.

A lot of clanking later, the doors opened.

“Master Sabrai is waiting,” one of the men told her. “He will meet you when you enter.”

The rules that governed visitors to the Oracular Halls were pretty simple: Don’t speak to anyone. Don’t touch anyone. Don’t react if someone screams and runs away at the sight of you.

The first time Kaylin had come up against these rules they had been confusing right up until the moment she’d entered the building. She understood them better now, and wasn’t surprised when she entered the Halls and saw a young girl teetering precariously on the winding steps that punctuated the foyer, singing to herself in a language that almost sounded like Elantran if you weren’t trying to make any sense of it.

Master Sabrai was, as the guard had suggested, waiting to greet them. Kaylin tendered him a bow; Severn tendered him a perfect bow. He nodded to each in turn, and Kaylin remembered, belatedly, that all visitors to these Halls were called supplicants.

Master Sabrai looked every inch the noble. His hair was iron-gray, and his beard was so perfectly tended it might as well have been chiseled. He wore expensive clothing, and if his hands weren’t entirely bejeweled, the two rings he did wear were very heavy gold with gems that suited that size. He had the bearing and posture of a man who was used to being obeyed.

Once that would have bothered Kaylin. In truth, in another man, it would have set her teeth on edge now.

“Private Neya,” Master Sabrai said. “Your companion?”

“Corporal Handred, also of the Hawks.”

“You have apprised him of the rules for visitors?”

“I have.” She grimaced, and added, “He’s better at following rules than I generally am. He’ll cause no trouble here.”

“Good. I am afraid that your visit here was not unexpected, and it is for that reason that I am here. Sigrenne is at the moment attempting to quiet two of the children, one of whom you met on a previous visit.”

“Everly? But he doesn’t talk—”

“No. He doesn’t. I was speaking of a young girl.”

Kaylin remembered the child, although she couldn’t remember the name. “She’s the one who saw—” She stopped. “She’s upset?”

“She had planted herself firmly in the door and would only be moved by force. She was not notably upset until her removal. I believe she was looking forward to reading you. Those were her exact words. She also,” he added, glancing at the covered mirrors that adorned part of the foyer, “attempted to decorate. She seemed to be afraid of the mirrors, which is not, with that child, at all the usual case. Come, please. Let us go to the Supplicant room.”

Sigrenne, still large and still intimidatingly matronly in exactly the same way as Marrin of the Foundling Hall—but without the attendant fur, fangs, and claws—was waiting for Master Sabrai in the Supplicant room. She was not on guard duty, so she didn’t resemble an armor-plated warrior, unless you actually paid attention to her expression.

That expression softened—slightly—when she caught sight of Kaylin. “You’re the Supplicant?” she asked.

“Well, sort of. One of the Supplicants, at any rate.”

“How is Marrin?”

“Doing really well. I swear, someone rich left all their money to the Foundling Halls. I’ve never heard so few complaints from her.”

“It’s probably the new kit.”

“You heard about him?”

“I saw him.” Sigrenne’s face creased in a smile that made her look, momentarily, friendly. “She brought him here when she came for her usual suspicious flyby.”

Some of the orphans left on the steps of the Foundling Halls ended up with the Oracles. Marrin, as territorial as any Leontine, still considered them her responsibility in some ways, so she made sure they were eating, dressing, and behaving as well as one could expect in the Oracular Halls.

Master Sabrai raised a brow at Sigrenne, and then threw his hands in the air, a gesture entirely at odds with both his dress and his generally reserved manner.

Sigrenne took this as permission to speak about matters that concerned the Oracles more directly. “You’re the only Supplicant we’re entertaining today. And that would mean you’re here by Imperial Dictate.” The last two words were spoken with very chilly and suspicious capitals.

Kaylin stiffened. “The other Supplicants?”

“Meetings have been postponed.”

“For how long?”

“Indefinitely. You can imagine how popular this has made Master Sabrai.”

If the Oracles did, indeed, see into the future—or the past—they often spoke in a way that made no bloody sense to anyone who couldn’t also see what they were seeing. Some of the Oracles didn’t speak at all, although that was rarer. But since the Emperor himself consulted with the Oracular Halls from time to time—and funded them—many powerful men and women thought they could gain some advantage by visits to the Oracles.

Those visits weren’t free, and they weren’t cheap. Kaylin, who sneered at the charlatans in Elani on a weekly basis, found the so-called real thing just as troubling, but for different reasons. She was mostly certain that the Supplicants who came with their questions couldn’t make heads or tails of the answers they actually got, and she couldn’t figure out why they’d spend the money at all.

But people with that much money could be really, really difficult if disappointed. She glanced at Sabrai. “Why have the Halls been closed to visitors?” she asked, in the no-nonsense tone she’d adopted while on formal Hawk business.

“I would imagine,” he replied, “that you have some suspicion, or Lord Sanabalis wouldn’t have sent you.”

“Is it like the last time?”

“No. Or at least, not yet.”

She waited.

So did he. And since he was used to dealing with people who could forget a conversation before they’d even finished a sentence, he won. “What do you mean when you say not yet?”

“There were a number of disturbing incidents today.”

“Were there any visual Oracles offered?”

“There were. They are not…unified, but there is a similarity of theme in some of them. It is not the visual that is of concern, and until we isolate the possible cause, we would prefer not to deal with the more trivial questions that cross this threshold. Why did the Emperor send you?”

“There were marked unusual disturbances in parts of the city today.”

“Unusual?”

“You could call them miraculous, given that we were on Elani.”

“How?”

“Some of the daily garbage that passes for magic on Elani actually seemed to work,” she replied.

He was silent for a few moments, staring just to the left of Kaylin’s shoulder.

“Master Sabrai,” Sigrenne said firmly.

He blinked, and shook his head. “My pardon, Sigrenne. I was…thinking.” His gaze became more focused, and his expression sharper. “And did incidents of this nature occur elsewhere?”

“Yes. I’m wondering, at this point, if they occurred here.”

“No. Or at least not in a fashion that would appear unusual to either myself or the caretakers. What question do you have for us?”

“I’ll get to that in a minute,” she replied, with a confidence she didn’t feel, because she didn’t actually have a question she wanted to hand to the Oracles. “Can you describe the unusual verbal incidents you’ve been experiencing?”

He hesitated for just a moment, and then said, “Let me see the letter you’re carrying.” It wasn’t what she was expecting, but she had no trouble handing it over. He, on the other hand, read it with care before he returned it.

“We have transcripts on hand,” he finally said. “They are less…useful…than normal, but in the past two days, a pattern seems to be emerging. The pattern involves fear—of monsters, of armies, of invasions. And,” he added, with a frown, “of doors.”

She watched the glance that passed between Master Sabrai and Sigrenne.

“There’s more.”

Master Sabrai nodded and massaged the bridge of his nose. “Everly is painting.”

CHAPTER 4

Everly wasn’t painting. He was stretching a canvas. He worked, as he always did, in silence; the only noises he made were the usual grunts physical effort produced. The canvas, however, was taller than he was, and it was almost as wide as it was tall. Kaylin looked at it, and then turned to Master Sabrai.

“When did he start?”

“Approximately two hours ago. We keep wood, nails, and canvas in the corner of his gallery.” The gallery in question was also the room he slept and lived in.