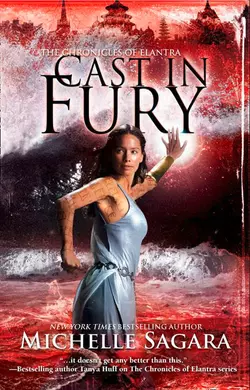

Cast In Fury

Michelle Sagara

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 382.20 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: When a minority race of telepaths is suspected of causing a near-devastating tidal wave, Private Kaylin Neya is summoned to Court—and into a PR nightmare.To ease racial tensions, the emperor has commissioned a play, and the playwright has his own ideas about who should be the focus. …But Kaylin works her best magic behind the scenes, and though she tries to stay neutral, she is again drawn into a world of politics…and murder.To make matters worse, Marcus, her trusted sergeant, gets stripped of his command, leaving Kaylin vulnerable. Now she’s juggling two troubling cases, and even magic’s looking good by comparison. But then nobody ever said life in the theater was easy. …