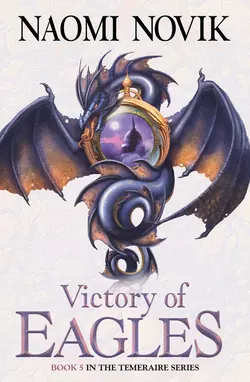

Victory of Eagles

Naomi Novik

The fifth instalment of the New York Times bestselling series, Temeraire. Laurence waits to be hanged as a traitor to the Crown, and Temeraire is confined to the breeding grounds as Napoleon invades Britain, and takes London.Laurence and Temeraire have betrayed the British. They have foiled their attempts to inflict death upon the French dragons by sharing the cure they found in Africa with their enemy.But following their conscience has a price. Laurence feels he must return to face the consequences, and as soon as they land they are taken into custody. Laurence is condemned to the gallows and Temeraire faces a life of captivity in the breeding grounds. None of their friends or allies can come to their aid, for every hand is needed elsewhere.Britain is completely unprepared for Bonaparte invasion and the advanced tactics of his own celestial dragon – Temeraire's mortal enemy – Lien.

NAOMI NOVIK

Victory of Eagles

Copyright (#ufc6c6828-520a-5394-bfaf-98803e721660)

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

HarperVoyager An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd. 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd. 2008

Copyright © Naomi Novik 2008

Cover design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd. 2014

Cover illustrations © Dominic Harman

Naomi Novik asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins ebooks

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication

Source ISBN: 9780007256761

Ebook Edition © FEBRUARY 2009 ISBN: 9780007318612

Version: 2017-04-28

For Dr. Sonia Novik

who gave this book a home

Table of Contents

Title Page (#ua0afb57c-b14f-5cde-90e4-066c69aace5a)

Copyright (#u54567eae-1ef3-5273-b43a-dd3fa04ddd69)

Dedication (#u9a2a0065-f67b-52a2-9414-9ef5fe7f5154)

Part I (#ucb550a3a-b1cf-50fa-aa27-854a77ed9ab6)

Chapter One (#u884afcdc-d9d4-5cfb-bd16-8390909d1c39)

Chapter Two (#u96549c99-980b-5d51-bfbf-d203fc388758)

Chapter Three (#ue07f6dd3-9ba9-53d4-8294-900c0038af93)

Chapter Four (#u26707c31-19cd-5dc3-abf0-737f54a9e501)

Chapter Five (#ucc18f9a7-4c10-5b89-b7aa-5b5f742c428d)

Chapter Six (#litres_trial_promo)

Part II (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Ten (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eleven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twelve (#litres_trial_promo)

Part III (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fourteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Sixteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Keep Reading (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

By the Same Author (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

PART I (#ufc6c6828-520a-5394-bfaf-98803e721660)

Chapter One (#ufc6c6828-520a-5394-bfaf-98803e721660)

The breeding grounds were called Pen Y Fan, after the hard, jagged slash of mountain rising like an axe-blade at their heart, rimed with ice along its edge and rising barren over the moorland. It was a cold, wet Welsh autumn already, coming on towards winter, and the other dragons were sleepy and remote, uninterested in anything but meals. A few hundred of them were scattered throughout the grounds, mostly established in caves or on rocky ledges, wherever they could fit themselves. No comfort or even order was provided for them, except for the feedings, and the mowed-bare strip of ground around the borders, where torches were lit at night to mark the lines past which they might not go. The town-lights glimmered in the distance, cheerful and forbidden.

Temeraire had hunted out and cleared a large cavern on his arrival, to sleep in; but it would be damp, no matter what he did in the way of lining it with grass, or flapping his wings to move the air, which in any case did not suit his notions of dignity. Much better to endure every unpleasantness with stoic patience, although that was not very satisfying when no-one would appreciate the effort. The other dragons certainly did not.

He was quite sure he and Laurence had done as they ought, in taking the cure to France, and no one sensible could disagree; but just in case, Temeraire had steeled himself to meet with either disapproval or contempt, and he had worked out several very fine arguments in his defence. Most importantly, of course, it had been a cowardly, sneaking way of fighting: if the Government wished to beat Napoleon, they ought to fight him directly, and not make his dragons sick to make him easy to defeat; as if British dragons could not beat French dragons, without cheating. ‘And not only that,’ he added, ‘but it would not only have been the French dragons who would have died. Our friends from Prussia, who are imprisoned in their breeding grounds, would also have gotten sick. And it might perhaps even have spread so far as China; and that would be like stealing someone else's food, even when you are not hungry; or breaking their eggs.’

He made this impressive speech to the wall of his cave, as practice. They had refused to give him his sand-table, and he had no-one of his crew to jot it down for him. He did not have Laurence, who would have helped him work out just what to say. So he repeated the arguments over to himself quietly, instead, so he would not forget them. And if these arguments did not suffice, he might point out that it was, after all, he who had brought the cure back in the first place – he and Laurence, with Maximus and Lily and the rest of their formation – and if anyone had a right to say where it should be shared out, they did. No one would even have known of it if Temeraire had not happened to be sick in Africa, where the medicinal mushrooms grew.

He might have saved himself the trouble. No one accused him of anything, nor, as he had privately, and a little wistfully thought possible, had they hailed him as a hero. They simply did not care.

The older dragons, not feral but retired, were a little curious about the latest developments in the war, but only distantly. They were more inclined to reminisce about their own battles from earlier wars, and the rest had only provincial indignation over the recent epidemic. They cared that their own fellows had sickened and died; they cared that the cure had taken so long to reach them; but it did not mean anything to them that dragons in France had also been ill, or that the disease would have spread, killing thousands if Temeraire and Laurence had not taken over the cure. They also did not care that the Lords of the Admiralty had called it treason, and sentenced Laurence to die.

They had nothing to care for. They were fed, and there was enough for everyone. If the shelter was not pleasant, it was no worse than what the dragons were used to, from the days of their active service. None of them had heard of pavilions, or ever thought they might be made more comfortable than they were. No-one molested their eggs; the groundskeepers took them away with infinite care in wagons lined with straw, and hot-water bottles and woollen blankets in the wintertime. They would bring back reports until the eggs were hatched and of no more concern; it was safer, even, than keeping them oneself, so even the dragons who had not cared to take a captain at all, would often as not hand over their own eggs.

They could not go flying very far, because they were fed at no set time but randomly, from day to day, so if one went out of ear-shot of the bells, one was likely to come too late, and go hungry. So there was no larger society to enjoy, no intercourse with the other breeding grounds or with the coverts, except when some other dragon came from afar, to mate. But even that was arranged for them. Instead they sat, willing prisoners in their own territory, Temeraire thought bitterly. He would never have endured it if not for Laurence; only for Laurence, who would surely be put to death at once if Temeraire did not obey.

He held himself aloof from their society at first. There was his cave to be arranged: despite its fine prospect it had been left vacant for being inconveniently shallow, and he was rather crammed-in; but there was a much larger chamber beyond it, just visible through holes in the back wall, which he gradually opened up with the slow and cautious use of his roar. Slower, even, than perhaps necessary: he was very willing to have the task consume several days. The cave had then to be cleared of debris, old gnawed bones and inconvenient boulders, which he scraped out painstakingly even from the corners too small for him to lie in, for neatness' sake. He found a few rough boulders in the valley and used them to grind the cave walls a little smoother, by dragging them back and forth, throwing up a great cloud of dust. It made him sneeze, but he kept on; he was not going to live in a raw untidy hole.

He knocked down stalactites from the ceiling, and beat protrusions flat into the floor, and when he was satisfied, he arranged some attractive rocks and dead tree-branches, twisted and bleached white along the sides of his new antechamber, with careful nudges of his talons. He would have liked a pond and a fountain, but he could not see how to bring the water up, or how to make it run when he had got it there, so he settled for picking out a promontory on Llyn y Fan Fawr which jutted into the lake, and considering it also his own.

To finish, he carved the characters of his name into the cliff-face by the entrance, although the letter R gave him some difficulty and came out looking rather like the reversed numeral four. When he was done with that, routine crept up and devoured his days. He would rise, when the sun came in at the cave mouth, take a little exercise, nap, rise again when the herdsmen rang the bell, eat, then nap and exercise again, and then go back sleep; there was nothing more. He hunted for himself, once, and so did not go to the daily feeding; later that day one of the small dragons brought up the grounds-master, Mr. Lloyd, and a surgeon, to be sure that he was not ill. They lectured him on poaching sternly enough to make him uneasy for Laurence's sake.

For all that, Lloyd did not think of him as a traitor, either. He did not think enough of Temeraire to consider him capable. The grounds-master cared only that his charges stay inside the borders, ate, and mated; he recognized neither dignity nor stoicism, and anything Temeraire did out of the ordinary was only a bit of fussing. ‘Come now, we have a fresh lady Anglewing visiting today,’ Lloyd would say, ‘quite a nice little piece; we will have a fine evening, eh? Perhaps we would like a bite of veal, first? Yes, we would, I am sure,’ providing the responses with his questions, so Temeraire had nothing to do but sit and listen. Lloyd was a little hard of hearing, so if Temeraire did try to say, ‘No, I would rather have some venison, and you might roast it first,’ he was sure to be ignored.

It was almost enough to put one off making eggs. Temeraire was growing uncomfortably sure that his mother would not have approved of how often they wished him to try, or how indiscriminately. Lien would certainly have sniffed in the most insulting way. It was not the fault of the female dragons sent to visit him, they were all very pleasant, but most of them had never managed to produce an egg before, and some had never even been in a real battle or done anything interesting at all. They were frequently embarrassed, as they did not have any suitable present that might have made up for their position; but it was not as though he could pretend that he was not a very remarkable dragon, even if he liked to; which he did not, very much. He would have tried to pretend for Bellusa, a poor young Malachite Reaper without a single action to her name, sent by the Admiralty from Edinburgh. She had miserably offered him a small knotted rug, which was all her confused captain would afford: it might have made a blanket for Temeraire's largest talon.

‘It is very handsome,’ Temeraire said awkwardly, ‘and so cleverly done; I admire the colours very much,’ He tried to drape it carefully over a small rock, by the entrance, but the gesture only made her look more wretched, and she burst out, ‘Oh, I do beg your pardon; he wouldn't understand in the least, and thought that I meant I would not like to, and then he said—’ and she stopped abruptly in even worse confusion, so Temeraire was sure that whatever her captain had said, it had not been at all nice. He had not even had the satisfaction of delivering one of his cherished retorts, because it was not as though she herself had said anything rude. So, although he had not much wanted to, he obliged anyway. He was determined to be patient, and quiet; he would not cause any trouble. He would be perfectly good.

Temeraire did not let himself think very much about Laurence; he did not trust himself. It was hard to endure the perpetual sensation of deep unease, almost overpowering when he thought of how he did not know how Laurence was, what his condition might be.

He was sure he knew where his breastplate was at every moment, and his small gold chain, these being in his own possession; his talon-sheaths had been left with Emily, and he was quite certain she could be trusted to keep them safe. Ordinarily he would have trusted Laurence, to keep himself safe; but the circumstances were not what they ought to be, and it had been so very long. The Admiralty had promised that so long as he behaved, Laurence would not be hanged, but they were not to be trusted, not at all. Temeraire resolved twice a week to go to Dover, at once, or to London – only to make inquiries, to see they had not, only to be sure. But unwanted reason always asserted itself, before he had even set out. He must not do anything that might persuade the Government he was unmanageable, and therefore that Laurence was of no use to them. He must be as complaisant and accommodating as ever he might.

It was a resolution already sorely tried by the end of his third week, when Lloyd brought him a visitor, admonishing the gentleman loudly, ‘Remember now, not to upset the dear creature, but to speak nice and slow and gentle, like to a horse,’ which was infuriating enough, even before the gentleman in question was named to him as one Reverend Daniel Salcombe.

‘Oh, you,’ Temeraire said, which made Salcombe look taken aback, ‘Yes, I know perfectly well who you are. I have read your very stupid letter to the Royal Society, and I suppose now you have come to see me behave like a parrot, or a dog.’

Salcombe stammered excuses, but it was plainly the case. He began laboriously to read to Temeraire a prepared list of questions, something quite nonsensical about predestination, but Temeraire would have none of it. ‘Pray be quiet; St. Augustine explained it much better than you, and it did not make any sense even then. Anyway, I am not going to perform for you, like some circus animal. I really cannot be bothered to speak to anyone so uneducated that he has not even read the Analects,’ he added, guiltily omitting Laurence; but then Laurence did not set himself up as a scholar, and write insulting letters about people he did not know, ‘And as for dragons not understanding mathematics, I am sure I know more on the subject than do you.’

He scratched out a triangle into the dust, and labelled the two shorter sides. ‘There; tell me the length of the third side, and then you may talk. Otherwise, go away, and stop pretending you know anything about dragons.’

The simple diagram had already perplexed several gentlemen, when he had put it to them during a party in the London covert, rather disillusioning Temeraire as to the general understanding of mathematics among the human populace. Reverend Salcombe evidently had not paid much attention to that part of his education either, for he stared, and coloured to his mostly bare pate. Then he turned to Lloyd furiously, ‘You have put the creature up to this, I suppose! You prepared the remarks—’ The unlikelihood of this accusation striking him, perhaps, as soon as he met Lloyd's gaping, uncomprehending face. He immediately amended, ‘they must have been given to you, by someone, and you fed them to him, to embarrass me—’

‘I never, sir,’ Lloyd protested, to no avail, and it annoyed Temeraire so much that he nearly indulged himself in a very small roar; but in the last moment he exercised great restraint, and only growled. Salcombe fled hastily all the same, Lloyd running after him, calling anxiously for the loss of his tip. He had been paid, then, to let Salcombe come and gawk at Temeraire, as though he really were a circus animal. Temeraire was only sorry he had not roared, or better yet thrown them both in the lake.

And then his temper faded, and he drooped. He realized too late, that perhaps he ought to have talked to Salcombe, after all. Lloyd would not read to him, or even tell him anything of the world. If Temeraire asked slowly and clearly enough to be understood, he only said, 'Now, let's not be worrying ourselves about such things, no sense in getting worked up. Salcombe, however ignorant, had at least wished to have a conversation; and he might have been prevailed upon to read something from the latest Proceedings, or a newspaper. Oh, what Temeraire would have done for a newspaper!

During this time the heavyweight dragons had been finishing their own dinners. The largest, a big Regal Copper, spat out a well-chewed grey and bloodstained ball of fleece, belched tremendously, and lifted away for his cave. Now the rest came in a rush, middle-weights and light-weights and the smaller courier-weight beasts landing to take their own share of the sheep and cattle, calling to one another noisily. Temeraire did not move, but only hunched himself a little deeper while they squabbled and played around him He did not look up even when one, with narrow blue-green legs, set herself directly before him to eat, crunching loudly upon sheep bones.

‘I have been considering the matter,’ she informed him, after a little while, around a mouthful, ‘and in all cases, where the angle is ninety degrees, as I suppose you meant to draw it, the length of the long side must be a number which, multiplied by itself, is equal to the lengths of the two shorter sides, each multiplied by themselves, added.’ She swallowed noisily, and licked her chops clean. ‘Quite an interesting little observation. How did you come to make it?’

‘I never did,’ Temeraire muttered, ‘it is the Pythagorean theorem; everyone who is educated knows it. Laurence taught it to me,’ he added, making himself even more miserable.

‘Hmh,’ the other dragon said, rather haughtily, and flew away.

But she reappeared at Temeraire's cave the next morning, uninvited, and poked him awake with her nose, saying, ‘Perhaps you would be interested to learn that there is a formula which I have invented, which can invariably calculate the power of any sum? What does Pythagoras have to say to that?’

‘You did not invent it,’ Temeraire said, irritable at having been woken up early, with so empty a day to be faced. ‘That is the binomial theorem, Yang Hui made it a very long time ago,’ and he put his head under his wing and tried to lose himself again in sleep.

He thought that would be the end of it, but four days later, while he lay by his lake, the strange dragon once again landed beside him. She was bristling furiously and her words tumbled over one another as she rushed, ‘There, I have just worked out something quite new: the prime number coming in a particular position, for instance the tenth prime, is always very near the value of that position, multiplied by the exponent one must put on the number p to get that same value – the number p,’ she added, ‘being a very curious number, which I have also discovered, and named after myself.’

‘Certainly not,’ Temeraire said, rousing with smug contempt when he had made sense of what she was talking about. ‘It is not p, it is e; you are talking of the natural logarithm. And as for the rest about prime numbers, it is all nonsense. Consider the prime fifteen—’ and then he paused, working out the value in his head.

‘You see,’ she said, triumphantly, and after working out another two-dozen examples, Temeraire was forced to admit that the irritating stranger might indeed be correct.

‘And you needn't tell me that this Pythagoras invented it first,’ the other dragon added, with her chest puffed out, ‘or Yang Hui, because I have inquired, and no-one has ever heard of either of them. They do not live in any of the coverts or anywhere around breeding grounds, so you may keep your tricks. Who ever heard of a dragon named anything like Yang Hui; such nonsense.’

Temeraire was neither despondent nor tired enough to forget how dreadfully bored he was, and so he was less inclined to take offence. ‘He is not a dragon, neither of them are,’ he said, ‘and they are both dead anyway, for years and years; Pythagoras was a Greek, and Yang Hui was from China.’

‘Then how do you know they invented it?’ she demanded, suspiciously.

‘Laurence read it to me,’ Temeraire said. ‘Where did you learn any of it, if not out of books?’

‘I worked it out myself,’ the dragon said. ‘There is nothing much else to do, here.’

Her name was Perscitia. She was an experimental crossbreed from a Malachite Reaper and a lightweight Pascal's Blue, who had come out rather larger, slower, and more nervous than the breeders had hoped for. Nor was her colouring ideal for any sort of camouflage. Her body and wings were bright blue and streaked with shades of pale green, with widely scattered spines along her back. Perscitia was not very old, either, unlike most of the once-harnessed dragons in the breeding grounds. She had given up her captain. ‘Well,’ Perscitia said, ‘I did not mind him. He showed me how to do equations, but I do not see any use in going to war and getting oneself shot at or clawed up, for no good reason. And, when I would not fight, he did not much want me anymore,’ a statement airily delivered, but Perscitia avoided Temeraire's eyes, making it.

‘Well, if you mean formation fighting, I do not blame you; it is very tiresome, Temeraire said. 'They do not approve of me in China,’ he added, to be sympathetic, ‘because I do fight. Celestials are not supposed to.’

‘China must be a very fine place,’ Perscitia said, wistfully, and Temeraire was by no means inclined to disagree. Sadly he thought, that if only Laurence had been willing, they might now be together in Peking, strolling in the gardens of the Summer Palace again. He had not had the chance to see it during autumn.

And then he paused, raised his head and said, ‘You made inquiries? What do you mean by that? You cannot have gone out?’

‘Of course not,’ Perscitia said. ‘I gave Moncey half my dinner, and he went to Brecon for me and put the question out on the courier circuit. This morning he went again, and received word that no one had ever heard of those names.’

‘Oh—’ Temeraire said, his ruff rising, ‘Pray; who is Moncey? I will give him anything he likes, if he can find out where Laurence is. He may have all my dinner, for a week.’

Moncey was a Winchester, who had slipped the leash at his hatching and eeled right out of the barn door, straight past a candidate he did not care for; and so made his escape from the Corps. Being a gregarious creature, he had been coaxed eventually into the breeding grounds more by the promise of company than anything else. Small and dark purple, he looked like any other Winchester at a distance, and excited no comment if seen abroad, or was absent from the daily feeding. As long as his missed meals were properly compensated for, he was very willing to oblige.

‘Hm, how about you give me one of those cows, the nice fat sort they save for you special, when you are mating,’ Moncey said. ‘I would like to give Laculla a proper treat,’ he added, exultingly.

‘Highway robbery,’ Perscitia said indignantly, but Temeraire did not care at all; he was learning to hate the taste of the cows, particularly when it meant yet another miserably awkward evening session, and he nodded on the bargain.

‘But no promises, mind,’ Moncey cautioned. ‘I'll put it about, have no fear, but it'll take many a week to hear back if you want it sorted out proper to all the coverts, and to Ireland, and even so maybe no-one will have heard anything.’

‘There is sure to have been word,’ Temeraire said quietly, ‘if he is dead.’

* * *

The ball came in down through the ship's bow and crashed recklessly the length of the lower deck, the drum-roll of its passage heralding its progression with castanets of splinters raining against the walls for accompaniment. The young Marine guarding the brig had been trembling since the call to go to quarters had sounded above; a mingling, Laurence thought, of anxiety, the desire to be doing something and the frustration at being kept at so miserable a post. A sentiment he shared from his still more miserable place within the cell. The ball seemed to be roll at a leisurely pace as it approached the brig. The Marine put out his foot to stop it before Laurence could protest.

He had seen the same impulse have much the same result during other battles. The ball took off the better part of the young man's foot and continued unperturbed into and through the metal grating, skewing the door off its top hinge before finally embedding itself, two inches deep into the solid oak wall of the ship. Laurence pushed the swinging door open and climbed out of the brig, taking off his neckcloth to tie up the Marine's foot. The young man was staring mutely at his bloody stump, and needed a little coaxing to limp along to the orlop. ‘As clean a shot as I have ever seen,’ Laurence said, encouragingly, and left him there for the surgeons. The steady roar of cannon-fire was going on overhead.

He climbed the stern ladder-way and plunged into the roaring confusion of the gun-deck. Daylight shining through jagged gaping holes in the ship's east-pointed bows, made a glittering cloud of the smoke and dust kicked up from the cannon. Roaring Martha had jumped her tackling, and five men were fighting to hold her long enough against the roll of the ship to get her secure again. At any moment, the gun might go running wild across the deck, crushing men and perhaps smashing through the side. ‘There girl, hold fast, hold fast—’ The captain of the gun-crew spoke to the canon as if she were a skittish horse, his hands flinching away from the smoking-hot barrel. One side of his face was bristling with splinters standing out like hedgehog spines.

No one knew Laurence in the smoky red light, he was only another pair of hands. His flight gloves were still in his coat pocket. Wearing them, he clapped on to the metal and pushed her by the mouth of the barrel, his palms stinging even through the thick leather, and with a final thump she heaved over into the channel again. The men tied her down and stood around trembling like well-run horses, panting and sweating.

There was no return fire, no calls passed along from the quarterdeck, no ship in view through the gun port. The ship was griping furiously where he put his hand on the side, a sort of low moaning complaint as if she were trying to go too close to the wind. Water glubbed in a curious way against her sides, a sound wholly unfamiliar, and he knew this ship. He had served on Goliath four years in her midshipman's mess as a boy, as lieutenant for another two and at the Battle of the Nile; he would have said he could recognise every note of her voice.

He put his head out of the porthole and saw the enemy crossing their bows and turning to come about for another pass She was only a frigate: a beautiful trim thirty-six gun ship which could have thrown not half of Goliath's broadside; an absurd combat on the face of it, and he could not understand why they had not turned to rake her across the stern. There was only a little grumbling from the bow-chasers above, not much of a reply to be making, though there was a great deal shouting.

Looking forward along the ship, he saw that she had been pierced by an enormous harpoon through her side, as if she was a whale. The end inside the ship had several curved barbs, which had been jerked back to bite into the wood. And when Laurence put his head out of the port-hole, he caught sight of the cable at the harpoon's other end swinging grandly up and up, into the air, where two enormous heavyweight dragons were holding on to it: a Grand Chevalier, and a Parnassian, middle-aged, likely traded to France during an earlier peacetime, and a Grand Chevalier.

It was not the only harpoon: three more cable-lines dangled from their grip to the bow, and Laurence could see another two stretched from the stern. The dragons were too far aloft for him to note all of the details, with the ship's motion underneath him, but the cables were somehow laced into their harnesses. By flying together and pulling, they were pivoting the ship's head into the wind. The dragons were too far aloft for round-shot to reach them. One of them sneezed, from the action of the frantic pepper guns, but they had only to beat their wings to get away from the pepper, hauling the ship merrily along while they did it.

‘Axes, axes,’ the lieutenant was shouting; then the clattering of iron as the bosun's mates came spilling weapons across the floor: hand-axes, cutlasses, knives. The men snatched them up and began to reach out of the portholes to hack at the ropes, but the harpoon shafts were two feet long, and the ropes had enough slackness to prevent good purchase. Someone would have to climb out of a porthole to saw at them: open and exposed against the hull of the ship, with the frigate coming around again.

No one moved at first; then Laurence reached out and took a short cutlass, from the heap. The lieutenant looked into his face, and knew him, but said nothing. Turning to the opening Laurence worked his shoulders out, hands quickly beneath his feet to support him, and eeled out as the lieutenant started calling again. Shortly, a rope was flung down to him from the deck above, so he could brace himself against the hull. Many faces peered over anxiously, all strangers; then another man came sliding down over the rail, and another, to work on the other harpoons.

Making a bright target against the ship's paintwork, Laurence began the grim effort of sawing away at the cable, strands fraying one at a time. The rope was cable-laid: three hawsers of three strands, well wormed and thick as a man's wrist, parcelled in canvas.

If he were killed, at least his family would be spared the embarrassment of his hanging. He was only alive now to be a chain round Temeraire's neck, until the Admiralty judged the dragon pacified enough by age and habit that Laurence might be dispensed. That could mean he faced years, long years, mouldering in gaol or in the bowels of a ship.

It was not a purposeful thought, no guilty intention; it only crossed his mind involuntarily, while he worked. He had his back to the ocean and could not see anything of the frigate or the larger battle beyond: his horizon was the splintered paint of Goliath's side, lacquered shine made rough by splinters and salt, and the cold sea was climbing up her hull and spraying his back. Distant roars of cannon-fire spoke, but Goliath had let her guns fall silent, saving her powder and shot for when they should be of some use. The loudest noises in his ears were the grunts and effort of the men hanging near-by, sawing at their own harpoon lines. Then one of them gave a startled yell and let go his rope, falling away into the churning ocean; a small darting courier-beast, a Chasseur-Vocifère, was plunging at the side of the ship with another harpoon.

The beast held it something like a jouster in a medieval tournament, with the butt rigged awkwardly into a cup attached to its harness, for support, and two men on its back bracing the rig. The harpoon thumped dully against the ship's side, near to where Laurence hung, and the dragon's tail slapped a wash of salt water up into his face, heavy stinging thickness in his nostrils and dripping down the back of his throat as he choked it out. The dragon lunged away again even as the Marines fired off a furious volley, trailing the harpoon on its line behind it: the barb had not bitten deep enough to penetrate. The hull was pockmarked with the dents of earlier attempts, a good dozen for each planted harpoon marring her spit-and-polish paintwork.

Laurence wiped salt from his face against his arm and shouted, ‘Keep working, man, damn you,’ at the other seaman still hanging near him. The first strand was going, tough fibres fraying away from the cutlass edge and fanning out like a broom. He began on the second, rapidly, although the blade was going dull.

The roar of the cannon made him jerk, involuntarily, and the ball came whistling across the water, skipping two, three times along the wave-tops, like a stone thrown by a boy. It looked as though it came straight for him, an illusion. The whole ship groaned as the ball punched at the bows, and splinters flew like a sudden blizzard out of the open portholes. They peppered Laurence's legs, stinging like a flock of bees, and his stockings were quickly wet with blood. He clung on to the harpoon arm and kept sawing; the frigate was still firing, her broadside rolling on, and the roundshot hurtled at them again and again. There was a sickening deep sway to Goliath's motion now as she took the pounding.

He had to hand the cutlass back and shout for a fresh one to get through the last strand. Then at last the cable was cut loose and swinging away free, and they pulled him back in. He staggered when he tried to stand, and went to his knees slipping in blood: stockings laddered and soaked through red; his best breeches, the ones he had worn for the trial, were pierced and spotted. He was helped to sit against the wall, and turned the cutlass on his own shirt, for bandages to tie up the worst of the gashes; no-one could be spared to help him to the surgeons. The other harpoons had been cut and they were moving at last, coming around. All the crews were fixed by their guns, savage in the dim red glow, teeth bared and mazed with blood from cracked lips and gums, their faces black with sweat and grime, ready to take vengeance.

Suddenly, a loud pattering like rain or hailstones came down: small bombs with short fuses dropped by the French dragons. Lightning flashes were visible through the boards of the deck. Some rolled down through the ladderways and burst in the gun-deck, hot flash-powder smoke and the burning glare of pyrotechnics, painful to the eyes. Then the cannon were speaking as they hove around in view of the frigate, and the order came down to fire.

There was nothing for a long moment but the mindless fury of the ship's guns going: impossible to think in that roaring din, smoke and hellish fire in her bowels choking away all reason. Laurence reached up for the port-hole when they had paused, and hauled himself up to look. The French frigate was reeling away under the pounding, her foremast down and hulled below the water-line, so each wave slapping away poured into her.

There was no cheering. Past the retreating frigate, the breadth of the Channel spread open before them. All the great ships of the blockade were as entangled and harassed as they had been. Bucephalas and the mighty Gloucester, both 100 guns, were near enough to recognize. They wore cables rising up to three and four dragons; a flock of French heavyweights and middleweights industriously tugging them every which way. The ships were firing steadily but uselessly, clouds of smoke that did not reach the dragons above.

And between them, half a dozen French ships-of-the-line, come out of harbour at last, were stately going by, escort to an enormous flotilla. A hundred and more, barges and fishing boats and even rafts in lateen rig, all of them crammed with soldiers, the wind at their backs and the tide carrying them towards the shore, tricolours streaming proudly from their bows towards England.

With the Navy paralysed, only the dragons of the Corps were left to stop the advance. But the French warships were firing something like pepper into the air above the flotilla, in quantities that could never have been afforded if it were. It burned. Red spark fragments glowed like fireflies against the black smoke-cloud hanging over the boats, shielding them from aerial attack. One of the transport boats was near enough that Laurence saw the men had their faces covered with wet kerchiefs and rags, or huddled under oilcloth sheets. The British dragons made desperate attempts to dive, but recoiled from the clouds, and had instead to fling down bombs from too great a height: ten splashing into the wide ocean for every one which came near enough to make a wave against a ship's hull. The smaller French dragons harried them too, flying back and forth and jeering in shrill voices. There were so many of them, Laurence had never seen so many: wheeling almost like birds, clustering and breaking apart, offering no easy target to the British dragons in their stately formations.

One great Regal Copper, who might have been Maximus: red and orange and yellow against the blue sky, flew at the head of a formation with Yellow Reapers in lines to each wing, but Laurence did not see Lily. The Regal roared, audible faintly even over the distance, and bulled his formation through a dozen French lightweights to come at a great French warship: flames bloomed from her sails as the bombs at last hit, but when the formation rose away again, one of the Reapers was streaming crimson from its belly and another was listing. A handful of British frigates, too, were valiantly trying to dash past the French ships to come at the transports: with some little success, but they were under heavy fire, and if they sank a dozen boats, half the men were pulled aboard others, so close were the little transports to one another.

‘Every man to his gun,’ the lieutenant said sharply. Goliath was turning to go after the transports. She would be passing between Majestueux and Héros, a broadside of nearly three tons between them. Laurence felt it when her sails caught the wind properly again: the ship leaping forward like an eager racehorse held too long. She had made all sail. He touched his leg: the blood had stopped flowing, he thought. He limped back to an empty place at a gun.

Outside, the first transports were already hurtling onward to the shore, lightweight dragons wheeled above to shield them while they ran artillery onto the ground. One soldier rammed the standard into the dirt, the golden eagle atop catching fire with the sunlight: Napoleon had landed in England at last.

Chapter Two (#ufc6c6828-520a-5394-bfaf-98803e721660)

The question sent out, Temeraire found the prospect of an answer almost worse. Before, the world itself had been undecided. If Laurence was still in it he might as easily stay alive as not, and so long as Temeraire continued to believe, Laurence was alive, at least in part. At best, the news would report that he was still imprisoned. As the day crept onward, Temeraire began to feel that certainty was a weak reward for the risk of receiving an answer to the contrary, a possibility Temeraire could not bear to envision. A great blankness engulfed him if he tried, like a grey sky full of clouds above and below, fog all around.

He wanted distraction badly, and there was none, except to talk to Perscitia, who was at least interesting, if infuriating also. Perscitia liked to think herself a great genius, and she was certainly unusually clever, even if she could not quite grasp the notion of writing. Occasionally, to Temeraire's discomfiture, she would leap quite far ahead, and come out with some strange notion, from none of the books Temeraire had read, that could neither be disproved, nor quarrelled with.

But she was so jealous of her discoveries that she flew into a temper when Temeraire informed her that any of them had been made before, and she was resentful of the hierarchy of the breeding grounds, which denied her the just desserts of her brilliance. Because of her middling size, she had to make do with an inconvenient poky clearing down in the moorlands, about which she complained endlessly. It provided little more than an overhang to shelter from the rain.

‘So why do you not take a better place?’ Temeraire said, exasperated. ‘There are several very nice ones directly over there, in the cliff face; you would be much more comfortable there, I am sure.’

‘One does not like to be quarrelsome’ Perscitia said being evasive and entirely false: she liked very well to be quarrelsome, and Temeraire did not understand what that had to do with taking an empty cave, either, but at least it diverted the subject.

The only event of note was that it rained for a week without stopping, with a steady driving wind that came in to all the cave-mouths and permeated the ground, and made everyone perfectly miserable. Temeraire was very glad of his antechamber, where he could shake off the water and dry before retreating to the comfort of his larger chamber. Several of the smallest dragons, courier-weights living in the hollows by the river, were flooded out of their homes entirely. Feeling sorry for their muddy and bedraggled state, Temeraire invited them to stop in his cavern, while the rain continued, so long as they first washed off the mud. They were, at least, loud with appreciation for his arrangements.

A few days later, when he was once again solitary and brooding over Laurence, a shadow crossed over the mouth of his cave. It was the big Regal Copper, Requiescat; he ducked in through the antechamber and came into Temeraire's main chamber, uninvited. He gazed around the room with an impressed air, and nodding said, ‘It is just as nice as they said.’

‘Thank you,’ Temeraire said, thawed a little by the compliment. He did not feel much like company, but remembered he must be polite. ‘Will you sit down? I am sorry I cannot offer you tea.’

‘Tea?’ Requiescat said absently. He was busy poking his nose into the corners of the cave, even putting his tongue out to smell them, as if he were at home; Temeraire's ruff began to bristle.

‘I beg your pardon,’ he said, stiffly, ‘I am afraid you have found me unprepared for guests,’ which he thought was a clever way of hinting that Requiescat might go away again.

But the Regal Copper did not take the hint; or at any rate he did not choose to go. but instead settled himself comfortably along the back of the cave and said, ‘Well, old fellow, I am afraid we will have to swap.’

‘Swap?’ Temeraire said, puzzled, until he divined that Requiescat meant caves. ‘I do not want your cave,’ adding hastily, ‘I am sure that it is very nice, but I have just got this one arranged to suit me.’

‘This one is much bigger now,’ Requiescat explained, ‘and it is much nicer in the wet. Mine,’ he added regretfully, ‘has been full of puddles all week; wet clear through to the back.’

‘Then I can hardly see why I would change,’ Temeraire said, still more baffled, and then he sat up, outraged and astonished, and let his ruff spread fully. ‘Why, you are a damned scrub,’ he said. ‘How dare you come here, and behave like a visitor, when all the time it is a challenge? I have never seen anything so devious in my life; it is the sort of thing Lien would do,’ he added, cuttingly. ‘You may get out at once. If you want my cave you may try to take it. I will meet you anytime you like: now, or at dawn tomorrow.’

‘Now, now, let us not get excited,’ Requiescat said soothingly. ‘I can see you are a young fellow, right enough. A challenge, really! It is nothing of the sort; I am the most peaceable fellow in the world, and I do not want to fight anyone. I am sorry if I was ham-handed about it. It is not that I want to take your cave, you see—’ Temeraire did not see, in the least, ‘—it is a question of appearances. Here you are a month, with the nicest cave, and you nowhere near the biggest either.’ Requiescat preened his own side, a little. He certainly outweighed any dragon Temeraire had seen, except Maximus and Laetificat. ‘We have our own little ways here, of arranging things to keep everyone comfortable. No one wants any fighting to cut up our peace, not when there is no need. It would be a nasty-tempered sort of fellow who would get to fighting over one cave versus another, both of them large and handsome; but distinctions must be preserved.’

‘Stuff,’ Temeraire said. ‘It sounds to me like you have become so lazy, having all your meals given to you and nothing to do, that you do not even want to put yourself to the trouble of properly bullying other people. Or maybe,’ he added, having made up his mind to be really insulting, ‘you are just a coward, and thought I was the same. Well, I am not, and I am not going to give you my cave, either, no matter what you do.’

Requiescat did not rise to the remarks, but only shook his head dolefully. ‘There, I am not a clever chap, so I have made a mull of explaining, and now your back is put up. I suppose we will have to get the council together, or you will never believe me. It is a bother, but it is your right, after all.’ He heaved himself back to his feet and added, infuriatingly, ‘You may keep the place until then; it will take me a day or so to get word to everyone,’ before he padded out again, leaving Temeraire quivering with rage.

‘His cave is the nicest,’ Perscitia said anxiously, later, ‘at least, we have certainly always thought so. I am sure you would like it, and maybe you could make it even more pleasant than this? Why don't you go and see it before quarrelling?’

‘I do not care if it is Ali Baba's cave, and full of gold and lamps,’ Temeraire said, not even trying to master his temper. It felt better to be angry than miserable, and he was glad of having something else to think about instead of that which he could do nothing to repair. ‘It is a question of principle. I am not going to be bullied, as though I were not up to fighting him. If I made the other cave nice, he would only try and take it back, I am sure. Or some other dragon would try and push me out. Who are this council?’

‘It is all the biggest dragons,’ Perscitia said, ‘and a Longwing, although Gentius does not bother to come out much anymore.’

‘All of them his friends, I suppose,’ Temeraire said.

‘Oh no; no one much likes Requiescat.’ Moncey said, perched on the lip of Temeraire's cave. ‘He eats so much, and will never take less, even if it's short commons all around. But he is the biggest, and there should not be fighting, so the general rule is that caves go by who is strongest if there is any quarrel. No one is allowed to take a place out of his class, or others will get jealous and squabble.’

‘You see, it is just as I told you: all unfairness,’ Perscitia said bitterly, ‘as if the only quality of any importance were one's weight, or how good one is at scratching and biting and kicking up a fuss; never any consideration for really remarkable qualities.’

‘I grant it has some practical sense as a way to choose caves,’ Temeraire said, ‘but it is nonsense that after I have taken one— One that he might have had at any time before I came, and did not want —he should be able to snatch it from me after I have gone to so much trouble to make it nice. And he is not stronger than me, either, if he does weigh more. I should like to know if he has sunk a frigate, alone, with a Fleur-de-Nuit on his back? And as for distinction, my ancestors were scholars in China while his were starving in pits.’

‘Be that as it may, he knows all the council, and you don't,’ Moncey said, practically. ‘You are hardly going to fight a dozen heavyweights at once, and beg pardon, but no one looking at you would say, “right-o, there is a match for old Requiescat.” Not that you are little, but you are a bit skinny-looking.’

‘I am not. Am I?’ Temeraire said, craning his head anxiously to look back at himself. He did not have spines along his back the way Maximus or Requiescat did, but was rather sleek; perhaps a bit long for his weight, by British standards. ‘But anyway, he is not a fire-breather, or an acidspitter.’

‘Are you?’ Moncey inquired.

‘No,’ Temeraire said, ‘but I have the divine wind. Laurence says that is even better.’ However, it belatedly occurred to him that perhaps Laurence might have been speaking partially; certainly Moncey and Perscitia looked blank, and it was difficult to explain just how it operated. ‘I roar, in a particular sort of way—I have to breathe quite deeply, and there is a clenching feeling, along the throat, and then—and then it makes things break—trees, and so on,’ Temeraire finished in an ashamed mutter, conscious that it sounded very dull and useless, when so described. ‘It is very unpleasant to be caught in it,’ he added defensively, ‘at least, so I understand from how others have reacted, if they are before me when I use it.’

‘How interesting,’ Perscitia said, politely, ‘I have often wondered what sound is, exactly; we ought to do some experiments.’

‘Experiments aren't going to help you with the council,’ Moncey said.

Temeraire switched his tail against his side, thinking, before saying with some distaste, ‘No, I see that: it is all politics. It is plain to me: I must work out what Lien would do.’

He cornered Lloyd, the next morning, and said, ‘Lloyd, I am very hungry today; may I have an extra cow, to take up to my cave?’

‘There, that is a little more like it,’ Lloyd said approvingly; not deaf at all to a request so satisfactory to his own ideas of dragon-husbandry. He ordered it directly, and while waiting Temeraire asked, attempting a casual air, ‘I do not suppose you might recall, who Gentius has sired?’

The old Longwing cracked a bleary eye, when Temeraire landed, and peered at him rather incuriously. ‘Yes?’ he said. His cave was not so large, but a comfortable dry hollow tucked well under the mountainside, on ground overlooking a curve of the creek; so positioned that he only had to creep downhill for a drink, and walk a short distance to a large flat rock full in the sun, where he presently lay napping.

‘I beg your pardon for not coming to visit you before, sir,’ Temeraire said, inclining his head, ‘I have served with Excidium these last three years at Dover—Your third hatchling,’ he added, when Gentius looked vague.

‘Yes, Excidium, of course,’ Gentius said, his tongue licking the air experimentally. Temeraire laid the cow down before him, butchered with the help of Moncey's small claws to take out the large bones. ‘A small gift to show my respect,’ Temeraire said, and Gentius brightened. ‘Why, that is trés gentil of you,’ he said, with atrocious pronunciation, which Temeraire remembered just in time not to correct, and took the cow into his mouth to gum at it slowly with the wobbly remainders of his teeth. ‘Most kind, as my first captain liked to say,’ Gentius mumbled reminiscently around it. ‘You might go in there and bring out her picture,’ he added, ‘if you are very careful with it.’

The portrait was rather odd and flat-looking, and the woman in it very plain, even before time and the elements had faded her; but it was in a really splendid golden frame, so large and thick that Temeraire could take it delicately between two talon-tips to lift it, and carry it out into the sun. ‘How beautiful,’ he said sincerely, holding it where Gentius could at least point his head in its direction, although his eyes were so milky with cataracts he could not have seen it as more than a blur in the golden square.

‘Charming woman,’ Gentius said, sadly. ‘She fed me my first bite, fresh liver, when my head was no bigger than her hand. One never quite gets over the first, you know.’

‘Yes,’ Temeraire said, low, and looked away unhappily; at least Gentius had not had her taken from him, and put who knew where.

When he had put the portrait back with equal care, and listened to a long story about one of the wars in which Gentius had fought – something with the Prussians, where pepper guns had been invented: very unpleasant things, especially when one had not been expecting them – then Gentius was quite ready to be sympathetic, and to shake his head censoriously over Requiescat's behaviour. ‘No proper manners, these days, that is what it is.’

‘I am very glad to hear you say so: that is just what I thought, but as I am quite young, I did not feel sure without advice from someone wiser, like yourself,’ Temeraire said, and then with sudden inspiration added, ‘I suppose next he will propose that if any of us have some treasure that he likes, gold or jewels, we must give it to him: it follows quite plainly.’

That was indeed enough to rouse Gentius up, with so handsome a treasure of his own to consider. ‘I do not see that you are wrong at all,’ he said, darkly. ‘Of course, we cannot have Winchesters taking caves fit for Regal Coppers, there would be no end of trouble and quarrelling, and sooner or later the men will involve themselves, and make it all even worse. They somehow think Reapers of less use than Anglewings, because there are more of them and they are clannish, instead of the other way round, and they have many more such odd notions. But that is not the same as taking away a cave perfectly suitable to your weight and standing.’ He paused and said delicately, ‘I do not suppose you had a formation of your own?’

‘No,’ Temeraire said, ‘at least, not officially. Arkady and the others fought under my orders, and I was wing-mates with Maximus: he is Laetificat's hatchling.’

‘Laetificat, yes; fine dragon,’ Gentius said. ‘I served with her, you know, in '76; we had a dust-up with the colonials at Boston. They had artillery above our positions—’

Temeraire came away eventually with Gentius's firm promise to attend the council-meeting, and returned to his cave pleased with the success of his primary efforts. ‘Who else is on the council?’ he asked.

While Perscitia began listing off names, Reedly, a mongrel half-Winchester, courier-weight with yellow streaks, piped up from the corner, ‘You ought to speak to Majestatis.’

Perscitia bristled at once. ‘I see no reason why he ought do any such thing. Majestatis is a very common sort of dragon; and he is not on the council, anyway.’

‘He made sure I got a share of the food, when we were all sick, and things were short,’ Minnow said, on the other side. She was a muddy-coloured feral with touches of Grey Copper and Sharpspitter and even a little Garde-de-Lyon, which had given her vivid orange eyes and blue spots to set off her otherwise drab colouring.

A low murmur of general agreement went around. A crowd had gradually accumulated in Temeraire's cave to offer their advice and remarks. A good many of the smaller dragons had interested themselves in Temeraire's case: those he had sheltered and their acquaintances, and the not-insignificant number, who had some injury, real or imagined, to lay at Requiescat's door. ‘And he is not on the council only because he does not care to be; he is a Parnassian.’ she said to Temeraire.

‘If he were a Flamme de Gloire, it would hardly signify,’ Perscitia said coldly, ‘as he does nothing but sleep all the time.’

Moncey nudged Temeraire with his head and murmured, ‘Corrected her once, six years ago.’

‘It was only an error of arithmetic!’ Perscitia said heatedly. ‘I should have found it out myself in a moment, I was only preoccupied by the much more important question—’

‘Where does he live?’ Temeraire asked, interrupting. He felt that anyone who had no time for politics must be rather sensible.

Majestatis was indeed sleeping when Temeraire came to see him; his cave was out of the way, and not very large. But Temeraire noticed that there was a carefully placed heap of stones, along the back, which blocked one's view into the interior. If he widened his pupils as far as they would go, he thought he could make out a darker space behind them, as if there were a passageway going back deeper into the mountainside.

He coiled himself neatly and waited without fidgeting, as was polite. But at length, when Majestatis showed no signs of waking, Temeraire coughed, then coughed again a little more emphatically. Majestatis sighed and said, without opening his eyes, ‘So you are not leaving, I suppose?’

‘Oh,’ Temeraire said, his ruff prickling, ‘I thought you were only sleeping, not ignoring me deliberately. I will go at once.’

‘Well, you might as well stay now,’ Majestatis said, lifting his head and yawning himself awake. ‘I don't bother to wake up if it isn't important enough to wait for, that's all.’

‘I suppose that is sensible, if you like to sleep better than to have a conversation,’ Temeraire said, dubiously.

‘You'll like it better in a few years yourself,’ Majestatis said.

‘I do not expect so,’ Temeraire said. ‘At least, the Analects say it is not proper for a dragon to sleep more than fourteen hours of the day, so I shan't, unless,’ he added, desolately, ‘I am still shut up in here, where there is nothing worth doing.’

‘If you think so, what are you doing here, instead of in the coverts?’ Majestatis said. He listened to the explanation with the casual sympathy of one listening to a storyteller, and passed no judgment, other than to nod equably and say, ‘A bad lot for you, poor worm.’

‘Why have you come here?’ Temeraire ventured. ‘You are not very old, yourself; do you really like to sleep so much? You might have a captain, and be in battles.’

Majestatis shrugged with one wing-tip, flared and folded down again. ‘Had one, mislaid him.’

‘Mislaid?’ Temeraire said.

‘Well,’ Majestatis said, ‘I left him in a water-trough, but I don't suppose he is still sitting there.’

He was not inclined to be very enthusiastic, even when Temeraire had explained,. He only sighed and said, ‘You are young, to be making such a fuss out of it.’

‘If I am,’ Temeraire retorted, ‘at least I am not complacent, and ready to let this sort of bullying go on, when I can do something about it; and I do not mean to be satisfied,’ he added, with a pointed look at the back of Majestatis's cave, ‘to arrange matters better only for myself.’

Majestatis's eyes narrowed, but he did not stir otherwise. ‘It seems to me you are as likely to make it worse for everyone at least. There's no wrangling now, and no one is getting hurt.’

‘No one is very comfortable, either,’ Temeraire said. ‘We all might have nicer places, but no one will work to improve theirs; they will not if they know it may be taken away from them, at any time, because they have made it nice. Once a cave is yours, it ought to be yours, like property.’

The council looked a little dubious at this argument, when Temeraire repeated it to them the next afternoon. Early that morning, the rain had been broken by a strong westerly wind sweeping the clouds scudding before it. They had gathered in a great clearing among the mountains, full of pleasant broad smooth-topped rocks, warmed by the sun. Majestatis had come after all, and Gentius, although the old dragon was mostly asleep after the effort of making the flight. He was curled up on the blackest rock, murmuring occasionally to himself. Requiescat sprawled inelegantly across half the length of the clearing, making himself look very large. Temeraire disdained the attempt and kept himself neatly coiled, with his ruff spread proudly, although he privately wished he might have had his talon-sheaths, and a headdress such as he had seen in the markets along the old silk caravan roads; he was sure that could not fail to impress.

Ballista, a big Chequered Nettle, thumped her barbed tail on the ground several times to silence the muttering that had arisen among the council, in the middle of Temeraire's remarks. ‘And if we agree that everyone may keep their own cave, when they have got it,’ Temeraire went on, valiantly, in the face of so much scepticism, ‘I would be very happy to share the trick of arranging them better. You all may have nicer caves, if you only take a little trouble to make them so.’

‘Very nice I am sure if you are a yearling’ one peevish older Parnassian said, ‘to be fussing with rocks and twigs.’

There were several snorts of agreement; and Temeraire bristled. ‘If you do not care to, and you are happy with your cave as it is, then you need not. But neither should you be able to take someone else's cave, when they have done all the work. I am certainly not going to be robbed as if I were a lump. I will smash the cave up myself and make it unpleasant before I hand it over meekly.’

‘Now, now.’ Ballista said. ‘There is no call to go yelling about smashing things or making threats; that is quite enough of that. Now we'll hear Requiescat.’

‘Hum, quarrelsome, isn't he,’ Requiescat said. ‘Well, you all know me chums and I don't mean to make a brag of myself, but I expect no one would say I couldn't take any cave I liked if I wanted to. I am not a squabbler, and don't like to hurt anybody; a young fellow like this is excitable enough to bite off a bigger fight than he can swallow—’

‘Oh!’ Temeraire said indignantly. ‘You may not claim any such thing, unless you should like to prove it. I have beaten dragons nearly as big as you.’

Requiescat swung his big head around. ‘Isn't it true you're bred not to fight? Persy was going about saying some such.’

Perscitia gave an angry yelp ‘I never!’ But was quickly stifled by the other small dragons sitting around her at Ballista's censorious glare.

‘Celestials,’ Temeraire said, very coolly, ‘are bred to be the very best sort of dragon. In China, we are not supposed to fight unless the nation is in danger, because China has a good deal more dragons than here and we are too valuable to lose. So we only fight in emergencies, when ordinary fighting dragons are not up to the task.’

‘Oh, China,’ Requiescat said dismissively. 'Anyway chums, there you have it plain as day. I say I am tops, and ought to have the best cave; he says it isn't so, and he won't hand it over. Ordinarily, there'd be no ways to work this out ‘cept with a tussle, and then someone gets hurt and everyone is upset. This is just the sort of thing the council was made up for, and I expect it ought to be pretty clear to all of you which of us is right, without it coming to claws.’

‘I do not say I am tops,’ Temeraire said, ‘although I think it likely. I say that the cave is mine, and that it is unjust for you to take it. That is what the council ought to be for. Justice, not squashing everyone down, just to keep things comfortable for the biggest dragons.’

The council, being composed of the biggest dragons, did not look very enthusiastic. Ballista said, ‘All right, we have heard everyone out. Now look, Teymuhreer,’ she pronounced it quite wrongly, ‘we don't want a lot of fuss and bother—’

‘I do not see why not,’ Temeraire said. ‘What else have we to do?’

Several of the smaller dragons tittered, rustling their wings together. She cleared her throat warningly at them and continued, ‘We don't want a lot of fighting, anyhow. Why don't you just go on and show us a bit of flying, so we know what you can do; then we can settle this.’

‘But that is not at all the point!’ Temeraire said. ‘It ought not make a difference if I were as small as Moncey—’ he looked, but Moncey was not among the little dragons observing, so he amended, ‘or if I were as small as Minnow there. No one was using it, no one wanted the cave before I had it.’

Requiescat gave a flip of his wings. ‘It was not the nicest, before,’ he said, in reasonable tones.

Temeraire snorted angrily. ‘Yes, yes; go on, then; unless you don't like us to see,’ Ballista said impatiently. That was too much to bear. He threw himself aloft, spiralling high and fast as he could, tightening into a spring, and then dived directly into formation manoeuvres, that was what would please them, he thought bitterly. He finished the training pass and backwinged directly, flying the pattern backwards, and then hovered in mid-air before descending sharply. He was showing off, of course, but they had demanded he do so. Landing, he announced, ‘I will show you the divine wind now, but you had better clear away from that rock wall, as I expect a lot of it will come down.’

There was a good deal of grumbling as the big dragons shifted themselves, with dragging tails and annoyed looks. Temeraire ignored them and breathed in deeply several times, stretching his chest wide, as he meant to do as much damage as he could. He noticed in dismay, that the crag was not loose, nor made of the same nice soft white limestone in the caves, which crumbled so conveniently. He scraped a claw down the rockface and merely left white scratches on the hard grey rock.

‘Well?’ Ballista said. ‘We are all waiting.’

There was no helping it. Temeraire backed away from the cliff and drew a preparatory breath. Then there was a hurried rush of wings above and Moncey dropped into the clearing beside him, panting, and said, ‘Call it off; it's all off,’ urgently, to Ballista.

‘Hey, what's this, now?’ Requiescat said, frowning.

‘Quiet, you fat lump,’ Moncey said, narrowing a good many eyes; he was not much bigger than the Regal Copper's head. ‘I'm fresh from Brecon. The Frogs have come over the Channel.’

A great confused babble arose all around, even Gentius roused with a low hiss, and while everyone spoke at once, Moncey turned to Temeraire and said, ‘Listen, your Laurence, word is in they locked him up on a ship called the Goliath—’

‘The Goliath!’ Temeraire said. ‘I know that ship. Laurence has spoken of it to me before. That is very good—That is splendid. I know just where it is, it is on blockade, and I am sure anyone at Dover can tell me exactly where—’

‘Dear fellow, there's no good way to say this,’ Moncey said. ‘The Frogs sank her this morning, coming across. She is at the bottom of the ocean, and not a man got off her before she went down.’

Temeraire did not say anything. A terrible sensation was rising, climbing up his throat. He turned away to let it come. The roar burst out like the roll of thunder overhead, silencing every word around him, and the wall of stone cracked open before him like a pane of mirrored glass.

Chapter Three (#ufc6c6828-520a-5394-bfaf-98803e721660)

They pulled the ship's boats into Dover harbour well past eleven o'clock at night, sweating underneath their wet clothing, hands blistered on the oars. They climbed out shivering onto the docks. Captain Puget was handed up in a litter, almost senseless with blood-loss, and Lieutenant Frye, nineteen, was the only one left to oversee. The rest of the senior officers were dead. Frye looked at Laurence with great uncertainty, then glanced around. The men offered him nothing, they were beaten with rowing and defeat. At last, Laurence quietly offered, ‘The port admiral,’ prompting him. Frye coloured and said to a gangly young midshipman, clearing his throat, ‘Mr. Meed, you had better take the prisoner to the port admiral, and let him decide what is to be done.’

With two Marines for guards, Laurence followed Meed through the dockside streets to the port admiral's office where they found nearly more confusion than had been on the deck of the Goliath in her last moments. After the double broadside had un-masted her, smoke had spread everywhere, fire crawling steadily down through the ship towards the powder magazine, as cannon ran wildly back and forth on her decks.

Here the hallways were suffocating with unchecked speculation. ‘Five hundred thousand men landed,’ one man said in the hallway, a ridiculous number, inflated by panic. ‘Already in London,’ said another, ‘and two millions in shipping seized,’ the very last of these being the only plausible suggestion. If Bonaparte had captured one or two of the ports on the Thames estuary and taken the merchantmen there, he might indeed have reached something like that number. He would have seized an enormous collection of prizes to fuel the invasion, like coal heaped into a burning stove.

‘I do not give a damn if you take him out and lynch him, only get him out of my sight,’ the port admiral said furiously, when Meed finally managed to work his way through the press and ask him for orders. There was a vast roar outside the windows like the wind rising in a storm, even though the night was clear. More petitioners were shoving frantically past them. Laurence had to catch Meed by the arm and hold him up as they fought their way out. The boy could scarcely have been fourteen and was a little underfed.

Set adrift, Meed looked helpless. Laurence wondered if he would have to find his own prison, but then one young lieutenant pushed through towards them, flung him a look of flat contempt, and said, ‘That is the traitor, is it? This way. You dogs take a damned proper hold of him, before he sneaks away in this press.’

He took up an old truncheon in the hallway, and swinging it to clear the way, took them out into the street. Meed trotted after him gratefully. The lieutenant brought them to a run-down sponging house two streets away, with bars upon the windows and a mastiff tied in the barren yard. It howled unhappily, adding to the clamour of the half-rioting crowd. A beating upon the door brought out the master of the house. He whined objections, which the lieutenant overruled one after another, but at last conceded.

‘Better than you deserve,’ he said to Laurence coldly, as he held open the door of a small and squalid attic. He was a slight young man with a struggling moustache. A solid push would have laid him out upon the unkempt floor. Laurence looked at him for a moment, and then stepped inside, stooping under the lintel. The door was shut upon him. Through the wall he heard the lieutenant ordering the two Marines to stand watch, and the owner's complaints trailing him back down the stairs.

It was bitterly cold. The irregular floor of warped and knotted boards felt strange under Laurence's feet, still expecting the listing motion of the ship. There was a handkerchief-square of a window, which at present let in only the thick smell of smoke. Shining rooftops, lit by a reddish glow, were all that he could see.

Laurence sat down on the narrow cot and looked at his hands. There would be fighting all along the coast by now. Men would have landed at Sheerness, and likely along points north, all around the mouth of the Thames. Not five hundred thousand, nothing like that, but enough perhaps. It would not take a very large company of infantry to establish a secure beachhead, then Napoleon could land men as quick as he could get them across the Channel.

This, Laurence would have said, could be not very quickly. Not in the face of the Navy. But that opinion fell before the manoeuvres he had witnessed today. Pitting great numbers of lightweights, easy to feed and quick to manoeuvre, against the British heavyweights, and using their own heavyweights against the British ships flew in the face of all common wisdom. But it bore the same tactical stamp as the whirling attack which he had witnessed at Jena, spearheaded by Lien. Laurence had no doubt her advice had also served Napoleon in this latest adventure.

Laurence had reported on the battle of Jena to the Admiralty. It was a bitter thought to know that his treason had now undermined that intelligence, and likely discredited all his reports. He thought Jane at least would still have kept it under consideration. Even if she had not forgiven him, she knew him well enough to know that his treason had begun and ended with delivering the cure. But from what he had seen of the battle, the British dragons were still locked in the same antiquated habits of aerial war.

The noises outside the window rose and fell like the sea. Somewhere nearby glass was breaking and a woman shrieked. The red glow brightened. He lay down and tried to sleep a little, but his rest was broken repeatedly by ragged eruptions of noise, falling back into the general din by the time he jarred awake, panting and sore. In his dreams, fragmentary images of the burning ship, which became glossy, black scales beneath the flames, curling and crisping at the edges. He rose once. There was a small dirty pitcher of water, but he was not yet thirsty enough to resort to it for a drink. He splashed his face with a cupped handful. His fingers came away streaked with soot and grime. He lay down again, there was more screaming outside, and a stronger smell of smoke.

It did not so much as grow light, as simply less dark. There was a thick sooty pall over the city, and his throat ached sharply. No one came with food, and he received not a word from his guards. Laurence paced his cell restlessly. Four long strides across, three lengthwise from the bed, but he used smaller steps and made it seven. His arms, clasped behind his back, felt as though they were weighted down with roundshot. He had rowed for five hours without a pause.

That at least had been something to do, something besides this useless fretting. The city was burning, and all he could do here was burn with it, or moulder to be taken a prisoner by the French, with Napoleon's army scarcely ten miles distant. And even if he died, Temeraire might never know. He might keep himself a prisoner long for lost cause, and be taken by the French. Laurence could not trust Napoleon with Temeraire's safety, not while Lien was his ally. Her voice, and the self-interest which would prompt him to be the master of the only Celestial outside China's borders, would be more persuasive than his generosity.

The guards might be tempted to let him out by their own desire to be gone, if only Laurence could convince himself he had any right to go. But he had been court-martialled and convicted, and justly so, with all due process of law. Though he would gladly have foregone the dragging out of evidence, he had been condemned already by his own voice. The panel of officers had listened with blank faces, tight with disgust. All were Navy officers, no aviator had been allowed to serve. Too many had been pulled into the vile business, implicated and smeared in any way they could be. Ferris, was singled out because Laurence must have confided in his first lieutenant. ‘And it must present a curious appearance to the court,’ the prosecutor had said, sneering, while Ferris sat drawn and pale and wretched and did not look at Laurence, ‘that he did not raise the alarm for an hour after the accused and his beast were known to be missing, and did not at once open the letter which was left behind—’

Chenery too had been named, and only because he had also been in London covert at the time. Berkley and Little and Sutton, were all brought in to give evidence, and if Harcourt and Jane had not been mentioned, it was only because the Admiralty did not know how to do so without embarrassing themselves more than their targets. ‘I did not know a damned thing about the business, and I am sure nor did anyone else. Anyone who knows Laurence will tell you he would not have breathed a word of it to anyone,’ Chenery had said defiantly. ‘But I do say that sending over the sick beast was a blackguardly thing for the Admiralty to have done, and if you want to hang me for saying so, you are welcome.’

They had not hanged Chenery, thank God, for lack of evidence and for need of his dragon, but Ferris, a lieutenant with no such protection, had been broken out of the service. Every effort Laurence had made to insist that the guilt was his alone had been ignored. A fine officer had been lost to the service, his career and his life spoilt. Laurence had met his mother and his brothers. They were an old family and proud. But Ferris had been away from home from the age of seven, so they did not have that intimate knowledge, which should make them confident of his innocence, and replace the affectionate support from his fellow-officers now denied to him. To witness his misery and know himself culpable hurt Laurence worse than his own conviction had done.

That had never been in any doubt. There had been no defence to make, and no comfort but the arid certainty that he had done as he ought. That he could have done nothing else. It offered scarce comfort, but saved him from the pain of regret. He could not regret what he had done, he could not have let ten thousand dragons, most of them wholly uninvolved in the war, be murdered for his nation's advantage. When he had said as much, and freely confessed that he had disobeyed his orders, assaulted a Marine, stolen the cure, and given aid and comfort to the enemy, there was nothing else to say. The only charge he contested, was that he had stolen Temeraire, too. ‘He is neither the King's possession nor a dumb beast. His choice was his own and it was freely made,’ Laurence had said, but he had been ignored, of course. He had scarcely been taken from the room before he was brought back in again to hear his sentence of death pronounced.

And then it had been quietly postponed. He had been hurried under guard, from the chamber and into a stifling, black-draped carriage. After a long rattling journey ending at Sheerness, he had been put aboard the Lucinda and then transferred to Goliath. He had been confined to the brig, an oubliette meant only to keep him breathing. It was a living death, worse than the hanging he was promised in future.