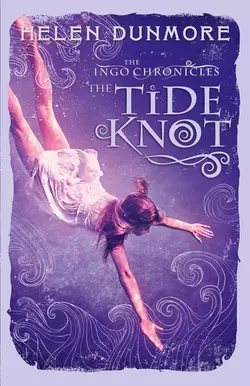

The Tide Knot

Helen Dunmore

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Сказки

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 612.81 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: The dramatic and spellbinding sequel to Helen Dunmore′s critically acclaimed ‘Ingo’.“I can’t go back in the house. I’m restless, prickling all over. The wind hits me like slaps from huge invisible hands. But it’s not the wind that worries me. It’s something else, beyond the storm…”Sapphire and Conor can’t forget their adventures in Ingo, the mysterious world beneath the sea. They long to see their Mer friends Faro and Elvira, and swim with the dolphins once more.But a crisis is brewing far below the ocean’s surface, where the wisest of the Mer guards the Tide Knot. And soon both Sapphire and Conor will be drawn into Ingo’s troubled waters…