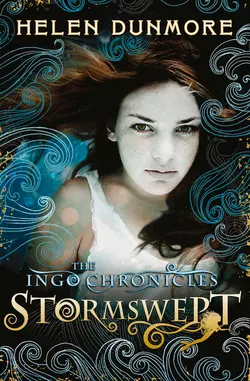

Stormswept

Helen Dunmore

An atmospheric and beautifully written adventure, from the award-winning author of the Ingo series.Morveren lives with her parents and twin sister Jenna on an island off the coast of Cornwall.As Morveren and Jenna’s relationship shifts and changes, like driftwood on the tide, Morveren finds a beautiful teenage boy in a rock pool after a storm. Going to his rescue, she is shocked to see that he is not human but a Mer boy.With Jenna refusing to face the truth, Morveren finds herself alone at the worst possible time. Because when the worlds of Air and Mer meet, the consequences can be terrible…

Dedication (#ulink_2c14717a-60aa-5a46-9892-2f7cd81418ec)

To Amber Ia

Contents

Cover (#uc938fa77-a3ac-5f83-bc84-236db7533dce)

Title Page (#ua869e8a7-b4fa-536f-abb9-85012506ab45)

Dedication

CHAPTER ONE

CHAPTER TWO

CHAPTER THREE

CHAPTER FOUR

CHAPTER FIVE

CHAPTER SIX

CHAPTER SEVEN

CHAPTER EIGHT

CHAPTER NINE

CHAPTER TEN

CHAPTER ELEVEN

CHAPTER TWELVE

CHAPTER THIRTEEN

CHAPTER FOURTEEN

CHAPTER FIFTEEN

CHAPTER SIXTEEN

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN

CHAPTER EIGHTEEN

CHAPTER NINETEEN

CHAPTER TWENTY

CHAPTER TWENTY-ONE

CHAPTER TWENTY-TWO

Copyright

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

orveren! We’ll get caught! Let’s go back and wait for the boat!” shouts Jenna, but I keep on running as if I haven’t heard. We’re nearly half-way across the causeway to the Island. Jenna won’t turn back without me. Sure enough, I hear her feet splashing over the cobbles behind me.

“Morveren!”

We can make it, I know we can. The tide has reached Dragon Rock and is pouring round it. We’ll get a bit wet maybe. I’m not turning back to wait for the boat now.

“Morveren!”

I don’t stop, but this time I look back. My sister is standing stock still on the causeway. The wind flails her hair over her face and the creeping water is already at her feet. I want to keep running but my feet won’t do it. Maybe she’s got a stitch. I race back to Jenna, and grab her hand. It’s cold, and her face is panicky. I pull her hard, but it’s like pulling a statue.

“We’ll drown if we stay here! You’ve got to run!”

The tide is coming in behind us too. We can’t go back to the mainland now, even if we want to. That’s the way the tide tricks you. When you’re looking ahead, the water slides in stealthily from behind. But we can still reach the Island if we run as fast as we can. Every second counts. I yank Jenna’s arm and she unfreezes.

“We can’t go back now, Jenna. Look, it’s too deep.”

She knows it. Jenna’s the sensible one usually, but if we stand here much longer it’ll be too late to go on as well as too late to go back. I’m hot all over with anger at myself. We should have waited for the next boat. Jenna wanted to, but I wouldn’t. Dad will be so angry if we get caught by the tide. There’s a refuge a hundred metres ahead but if we have to climb up there someone’s got to bring a boat out to rescue us and everyone will know how stupid we’ve been.

We race as fast as we can over the causeway cobbles. Our feet slip, slide and splash. The tide’s not racing, but it’s coming in relentlessly, pulse after pulse. The stones are almost underwater now. Here’s the refuge, standing firm with its ladder and iron handholds. It’s only just been rebuilt because the old one was swept away by last winter’s storms. We pound past it without slowing down. We don’t have to discuss it because Jenna feels the same as I do. We’re not going to be stuck up there, waving for help like tourists. There’s no mobile reception out here, or on the Island.

Jenna and I run on side by side, clutching hands. If anyone saw us we’d get in so much trouble. It’s only because I had a detention and Jenna waited for me that we were both late. The sea’s putting out claws of grey water now, slopping over our feet. Surely the causeway will start to slope upwards soon, to the Island shore. Rain’s driving in too, big flapping sheets of rain that hide the rocks. But we’re nearly there. All that scares me is the way the water keeps on getting deeper. If it rises past our knees there’s a danger that the tide will be strong enough to push us off the causeway into deep water. We could be swept away.

The sea is pushing us now. It wants to win. You only have to make one mistake, Dad always says, because the sea never makes any. All our lives we’ve been taught to respect the sea. Dad would go mad if we got swept away.

Jenna stumbles. My shoulder wrenches as I drag her upright.

“Quick, Jenna!”

But as I pull her I lose my balance and my foot turns on the cobbles under the water. This time it’s Jenna who hauls me back.

We’re nearly there. It’s going to be all right. My legs hurt because it’s so hard to run when you’re almost knee-deep in water. We wade and slither and stumble, shoving ourselves forward as if we’re running in a nightmare. The water licks our legs hungrily, but it’s not going to get us this time, because suddenly, with a rush of relief, I see that the outline of the cobblestones below us is getting sharper again. The water’s falling. The causeway’s rising. We’ve made it.

At that moment the strangest thing happens. I stop fighting the swirl of the sea around my legs. I slow down. The smell of salt fills my head as a curtain of rain moves across my field of vision and hides the Island. A herring-gull swoops down, combing the air above my head. The tide shoves in, almost lifting me off my feet.

And for a moment I want to be lifted. I want to know where the surging tide will take me. If only I could fly through the water like that gull which is skimming away, free, towards the horizon… My mind fills with longing and for a few seconds everything else is crowded out. Even Jenna, my twin sister, closer to me than I am to myself – Jenna vanishes from my thoughts. Grey water, glistening water, the smell of salt—

But Jenna’s tearing at my hand. “Morveren! Morveren!”

The feeling fades, like waking from a dream. I try to snatch it back as the gull screams in the distance, but it’s gone.

“Hurry, Morveren!”

We wade through the shallows as the causeway rises and the grip of the tide releases us. It’s just water now. We’re safe, and suddenly the sea is cold, freezing cold, and all I want is to be in front of the fire at home.

Panting and wet, we haul ourselves up the last few metres, scramble up the slipway and collapse against the harbour wall, hoping no one will be about. But of course, Jago Faraday’s lounging around as usual, even though it’s now pouring with rain. There’s nothing he likes better than someone else having a bad time.

“Cutting it a bit fine, my girl,” he says to me, frowning as if it’s all my fault that we nearly got caught by the tide. “You keep your sister away from the water.”

To say that Jago has favourites is an understatement. He loves Jenna and hates me. He calls us the good ’un and the bad ’un. It’s supposed to be a joke – the kind of joke which is not funny when you are the butt of it.

“You been getting your sister into trouble again.”

Jenna is exactly the same age as me: in fact she is twelve minutes older. So how is it that I’m always supposed to be the one who leads her into trouble? But I don’t say this. Backchat will make him more likely to tell Mum and Dad that not only have I nearly drowned Jenna, but I gave him lip as well.

“I shan’t tell your mum and dad,” says Jago, as if he’s read my mind. “I can keep a secret.”

I’m relieved in a way, but I don’t want to share any secrets with Jago Faraday. He’s a spiteful, mean old man. But Jenna smiles at him, and then Jago’s face changes completely as he smiles the creaky old smile that only she ever gets. “You go on home and warm yourself, my maid,” he says to her, in his special Jenna voice. Never mind if I die of pneumonia, as long as Jenna’s warm. I look sidelong at Jenna, and pull a face, but unfortunately she is still smiling at Jago.

Our school shoes are sodden, and our tights too. Our coats are not too bad.

“If we stuff our shoes with newspaper and put them near the stove, they’ll dry out all right,” says Jenna. “Lucky it’s raining. Mum won’t notice.”

“I should have skipped detention. No one except Mr Cadwallader would give a detention on the last day before half-term.”

“You’d have got a double one.”

“Yes, but I wouldn’t have had to do it for more than a week… Jenna? Have you ever had a detention?” I know she hasn’t.

“Well… I haven’t yet,” says Jenna cautiously, because she doesn’t want to make me feel bad.

“You haven’t ever, you mean. Do you realise how much easier my life would be if you weren’t so good?”

“Mum won’t ask why we were late. We’ll just say we missed the boat.”

“OK.”

Mum will find out anyway at the end of term, when she sees my report. They always put detentions on reports, but that’s a good long way off and anything could happen before then. If only Jenna didn’t bring her report home at exactly the same time, mine wouldn’t look so bad. If my parents compared my report with Bran Helyer’s, for instance, they’d be quite happy. Ecstatic, even…

“Couldn’t you throw a few crisp packets round the classroom, Jen? Or tell Mr Kernow you didn’t fancy doing your maths homework?”

Jenna stares at me. “Why would anyone do that?” is written all over her face.

“Bran was in detention today,” I say casually.

Jenna’s face shadows. It’s complicated. All through primary school she and Bran were friends. No one else liked him, though he had a gang for a while. But the gang got too violent even for the people who were in it. Soon, Bran was a gang of one, and everybody left him alone.

Mum used to say, “Bran doesn’t have much of a life, with that father of his,” as if she were sorry for him. No one else was: they were too scared of him. But then something changed between Jenna and Bran. People think that twins tell each other everything, but that’s not true. Jenna doesn’t need to tell me, anyway. I can feel the difference in her. She might not be friends with Bran any more, but if someone talks about him, Jenna always reacts. It’s not obvious, because nothing with Jenna is obvious, but it’s there. I can sense what Jenna’s thinking most of the time and I know from the way she looks at Bran (which, being Jenna, she rarely does any more) that even if they aren’t friends, there’s still a link between them. But Bran is too much of a bad boy for Jenna now.

“Was he?” says Jenna now, in a carefully neutral voice.

“What?”

“In detention. Bran.”

“Yeah. He walked out halfway through though. He’ll get suspended again, I think.”

Jenna flinches.

“Bran won’t care about a suspension, Jen.”

“His dad hits him,” says Jenna in a low voice. She may not be friends with Bran any more, but she still knows a lot more about him than anyone else does. But the fact that Bran’s dad is violent isn’t exactly news. He used to live on the Island, when he was still married to Bran’s mum, because she’s an Islander, like us. She’s gone away, upcountry. I think Bran still sees her, but I’m not sure. I look at Jenna. She’s frowning and her face is full of worry. Jenna hates any kind of violence. Even the kind of fights boys have in primary school used to make her hide away in the girls’ toilets.

Mum and Dad aren’t at home. Mum’s left a note telling us that they’re rehearsing with Ynys Musyk in the village hall. Digory’s gone with them and there’s a stew in the oven. Ynys Musyk is our island band. Everybody plays in it more or less, although not Jago Faraday. The only time he even sings is at funerals, very loud and very flat. There’s a reason why our band is so important, but it’s complicated. We don’t usually talk about it to outsiders, because they wouldn’t believe it. They’d probably think it’s just a legend, one of those stories for tourists.

Digory is our little brother. He’s seven and he plays the violin. I do too, but Digory’s playing is something different. In the summer, when the visitors come, they hear Digory practising and they tell Mum and Dad that something ought to be done for him, as if Mum and Dad are too stupid to know how good Digory is. (Some tourists think that because there’s no mobile signal on the Island, and we don’t have broadband, that we are out of touch with the real world.) They say that Digory ought to go away to a music school on the mainland, to develop his talent. But Mum tells Digory to go and practise away down by the shore where nobody will hear him. She doesn’t want Digory leaving home, and nor do any of us. It’s bad enough that we have to go to school on the mainland once we’re past the Infants, because there aren’t enough of us to be educated here. At least we come home every night. The music school would be far away upcountry and Digory would have to board there. He would hate that.

When you grow up on an island you don’t ever want to leave it. It gives you such a safe feeling when the water swirls all around and no one can get to you. No, not safe exactly… Complete. As if you have everything that you will ever need, and nothing that you don’t need. Even though a causeway connects us to the mainland at low tide, we are still a true island. Sometimes in winter, when there’s a storm, we can’t go to school for days. I love the season of storms. No one can reach us then. We are supposed to keep up with school worksheets and reading, but even Jenna doesn’t bother.

Some people say that the sea is rising year by year, and the coastline will slowly crumble away as it retreats from the oncoming water. If that happens, we’ll be cut off from the mainland even at low tide. I’d like it, but other people say we couldn’t survive like that, and we’d have to build up the causeway, even though it would cost millions. Otherwise the tourists won’t come, and most of our income will be gone. It’s hard to make money here. The only jobs are fishing and tourism, unless you’re a doctor or a nurse or something like that. Mum has a part-time job in the post office.

Jenna stuffs our shoes with newspaper and washes the salt water out of our tights, while I put on potatoes to go with the stew. It is dark outside now, but inside it’s warm and you can smell the bread Mum made earlier, which is cooling on racks in the kitchen, ready for the freezer. The wind is blowing hard. The sea is beating up, and even with the door and windows closed we can hear the waves thump on the rocks. There will be deep water now where Jenna and I stood on the causeway. I shiver. Sometimes it frightens me, how quickly the world can shift between safety and danger. I want to retreat into a small, secure space. But at other times, risk pulls me like a magnet. I remember that strange feeling, when the sea almost lifted me off the causeway. I wanted it to lift me. Where did I want it to take me?

Maybe Jago Faraday is right, and I’m leading Jenna into trouble. She is so cautious and sensible. She would never take a risk unless I did, but then she would always follow me.

“You should dry your hair, Morveren,” says Jenna. “It’s dripping down your back.”

We both have long dark hair that reaches almost to our waists. When we were little Mum used to give us different partings, so that other people knew which one of us they were talking to, and she would buy blue hairbands for Jenna and green for me, because those were our favourite colours. We don’t bother with any of that now. If people don’t see that our characters are completely different, and that makes our faces different too, then let them go on mixing us up.

A thought strikes me. “You could do my detention for me next time.”

“It would still get written into your school diary,” says Jenna, who has clearly worked this out long ago. Otherwise, she would do the detention for me, I think. Jenna’s like that.

There’s a bang at the window, and I jump.

“That shutter’s come loose again,” says Jenna calmly.

“I’ll fix it,” I say, and before she can offer to help, I slip out of the door.

The night is wild now, full of wind and rain. All the cottages on the Island have shutters, to protect the glass in the windows from winter storms. I grab the loose shutter as it slams against the sill, and wedge in the hook that holds it. The wind whips my hair and I taste salt on my lips. Sometimes, when there is a storm, salt spray flies right over the Island. We go down to the headland and watch the waves battering the Hagger Rocks. I could go there now. I can find my way in the dark. I know every stone of the Island – we all do.

The wind whirls round the corner of our cottage. It’s pushing me, folding around me. The branches of our tamarisk tree whip above my head. How strange – I’m not by the window now, I’m already at the gate. The wind is shoving me along as if it knows where it wants me to go. My hand is on the latch. I open it, and now the wind seizes hold of me, carrying me with it, almost lifting me off my feet.

hen a storm is raging, I feel ten times more alive. Storms are in my blood, because of the way our island came to be, and the way I came to be here.

Long ago, there was no Island, and no wide bay full of sea. Mainland and Island were all one. There was solid land here, where our ancestors built a great city. It had wide streets and rich houses, and a hall as big as a cathedral, where they held gatherings. Everybody in that city loved music, and they would come together to play and sing and dance all night long, until they went home in the grey light of dawn.

But one night everything changed. The hall was packed with people. There was a great gathering, with music that was going to play all night long. There were fiddles and bodhrans, bagpipes, whistles and harps. The music flooded out, and in spite of the crowd everybody was dancing. All you could hear was the skirl of the band and the stamp of hundreds of feet.

That’s why nobody heard the change in the wind. It had been blowing a gale all day, but our ancestors were used to gales and bad weather, just as we are. They didn’t let it stop their celebrations. The wind grew louder and louder, louder than any wind that had ever been heard in that land. It roared around the roof like an express train, and as it blew the sea began to move.

It moved slowly and stealthily at first, as if it didn’t want to alarm anyone. Only one person saw what was happening, and that was a boy who was perched up on his father’s shoulders so that he could see everything. The windows were high up in the walls and only the boy could look out of them. He turned, just as the moon broke free of the raging clouds and shone out. The boy saw the wild, foaming waves flatten as if a giant hand were pressing down on them. And then, very slowly the sea began to move backwards, as if it were swilling away down a giant plughole.

The boy blinked. He couldn’t believe what he was seeing.

“Dad! Dad!“ he shouted. “The sea’s going backwards!”But his father didn’t hear him above the noise in the hall. The boy stared with his mouth open. In the far distance, where the sea had gone, he saw a wall of water, higher than any wave he had ever surfed, higher than any house, far higher than the walls of the great hall. It was as black as night with a crest of curling foam. It was moving, but not backwards now. It was coming in towards the land.

The boy cried out, so loud that this time his voice was heard above all the noise in the hall:

“The sea! The sea’s coming!”

People close by frowned at him for screaming like that. The band kept on playing, but one man heard the terror in the boy’s voice, and he went to the doors at the back of the hall and pulled them open. Outside it was almost dark. The air streamed with spray until it was hard to see anything. But the moon shone out and then the man saw what the boy had seen: a wall of water advancing slowly but with terrifying force, as if nothing in the world could stop it. The hair on his scalp prickled. A cold wind roared through the hall from the open door. At the same moment the man’s voice rang out like a trumpet:

“The sea’s coming! Run for your lives!”

The fiddler stopped playing, with his elbow raised. Everyone stood frozen for a second and then a wave of panic rushed through the crowd. People began to shove towards the door, grabbing their children and their loved ones. Some clambered up to the windows and there was the crash of breaking glass, and then a scream. The blind fiddler held his fiddle high. Whatever happened, he would protect what was most precious to him. He couldn’t see what was happening but he could smell the panic and hear the cries of parents calling for their children:

“The sea’s coming! Cador, where are you? Tamasin! Tamasin!”

“The sea’s coming! We’ll be trapped!”

They’d lived with the sea all their lives. They knew all about storms, but this they had never seen. Those at the back of the hall could see the wall of water rushing towards them, reaching for them, as they fought to get out of the doors.

The boy on his father’s shoulders saw the blind fiddler holding his fiddle high. He bent down and shouted into his father’s ear above the roar of the water and the screams and cries:

“Father! We must help him! He can’t find the door!”

In a few strides the boy’s father made his way along the wall, away from the crowd pressing towards the doors. The jam of people was too dangerous now, the father judged. His boy would be crushed. He would try to get the boy to safety another way, and the blind fiddler, if he would come with them.

They begged the fiddler to follow them, but he refused.

“You’ve got your young one,” he said. “Take my fiddle and run for the highest ground.”

The blind man put his fiddle into the boy’s arms, and the boy held it high. The father climbed on a chair, smashed a window and knocked out the glass with his boot. He lifted his boy high, still holding the fiddle, and put him up on the window ledge. The boy clung to the stone frame. Outside it was dark and the ground was a long way down.

“Jump!” he said. “Jump! I’m coming after you!”

The boy jumped. He landed on his feet then stumbled and fell on one knee, but still he held the fiddle safe. He looked up for his father, but his father shouted, “Run! Run, Conan! I’m coming after you! Run for the highest ground! I’ll be right behind you! Run!”

The boy obeyed his father, and ran. He could hear the gathering roar of the sea, and ahead of him he could see the shadow of the Castle Mound, which was the highest place for miles. He held the fiddle in his arms and ran until his breath burned in his lungs, and his heart was pounding. The sea was behind him. He didn’t dare to turn. It was like a wild animal, roaring at his heels. In front of him the bulk of the Mound grew clearer. He was almost there. Just a few more breaths, just a few more desperate pounding steps. His feet were on the rock. He was stumbling, falling, with the fiddle held high above his head to keep it clear of the water. At that moment an arm reached out and dragged him up on to the rock, and held him tight. He was safe on the Mound.

But where was his father? He looked behind him and saw the wall of water below him. In the moonlight he saw hundreds of figures running for their lives, but the water was gaining on them. His father had no one to lift him up to the window frame! How would he escape? Conan cried out in horror as he realised the sacrifice his father had made. He thrust the blind man’s fiddle into the arms of a woman who was shivering beside him.

“Keep it safe!” he shouted, and he turned and plunged back downhill.

The wall of water broke long before it reached the boy. Its force swelled over the city and swept away everyone in its path. The great hall filled with salt water, and out of all the people who had played and danced that night, only a handful ever reached the safety of the Mound. The power of the water spread out over the land, covering it, turning miles of fertile fields and a great city into a bay full of raging sea. The water boiled with wreckage. The air was filled with sobs and cries and curses, as the people of the city gave up their lives.

But the boy was still alive. The water seized him, hurled him high into the air, and then plunged him down into its depths. His lungs were bursting but he kicked and fought his way back to the surface. All his experience of growing up by the sea came to his aid as the currents of the storm clawed at him.

“Don’t panic,” Conan told himself. “Don’t fight the current, go with it until you can swim across it.”

Everywhere around him there was blackness. Cloud had come over the moon and Conan couldn’t even see where the great hall had been. He shouted again and again for his father, as he struggled to keep afloat. No one answered. Salt water filled his mouth and he coughed and spat and choked. The sea was too strong. It had got hold of him and it wasn’t going to let him go. Bright speckles danced in the blackness in front of his eyes and he remembered his father’s words,

“You only have to make one mistake, Conan, because the sea never makes any.”

Another wave broke over his head, pushing him down.

At that moment a strong arm came around him. Conan was rising up to the surface again. There was air and he could breathe. Someone was holding him up, holding him so strongly that the sea had no power to pull him away.

They were swimming across the current now, more powerfully than the boy had ever swum in his life. The waves were calming, and the moon had once more pushed the clouds aside. Ahead of him, Conan saw the Mound rising against the sky. At that moment the grip on him loosened. The boy turned and saw a face he didn’t know, with long hair streaming around it like seaweed. It was not his father who had saved him. The man pointed ahead, as if showing Conan the way he must go to safety. Land was very close. The boy trod water, and then his foot brushed against sand. Coughing and choking, the boy dragged himself into the shallows and lay there gasping for breath.

When he looked up, the man who had helped him had disappeared.

Conan never saw his father again. The other survivors became his family. As dawn broke they huddled together on the Mound, with the wide, grey, stormy sea all around them. Castle Mound had become an island. Their city and their homes had vanished beneath the waves. The survivors had no possessions, except for the clothes they were wearing and the blind man’s fiddle. But they had their lives, to start all over again, and they had their memories.

They remembered the music they used to play. As time went on they got other instruments from the mainland: bodhrans, flutes, bagpipes. They played the music of the lost city, even though it made them sad at first. They remembered what their lives had been like, and they built a new community, and a future for themselves and for their children, on the Island. Conan grew up, and became a great fiddle player. People said that he played almost as well as the blind fiddler who drowned in the flood.

Conan never forgot the arm that had reached out from the water and brought him safe to land. No human arm could have had the strength to hold him against that wall of water. No human being could have swum against the current and brought him to the Island.

Years later, when Conan had children and grandchildren of his own, he passed down to them the story of his rescue. He wanted it to be remembered for ever, and it is. I remember it, Jenna and Digory remember it. Our parents told us the story just as their parents told it to them, and back and back for as long as anyone knows. Conan is my ancestor. My great-great-great-great… I don’t know how many greats. He always kept the blind man’s fiddle safe, and we have it safe still. We call it Conan’s fiddle.

When Digory is old enough for a full-sized fiddle, that’s the one he will play. It’s too big for him now. Sometimes he takes it out of its case, just to try it, and to stroke the rich curve of the wood. Maybe some of the blind fiddler’s spirit has stayed in his instrument, because Digory says it is full of music. If anyone can find that music, Digory can. After a while we wrap the fiddle again in its blue velvet cloth, and put it back in the case. Some people say that if the fiddle is ever lost or broken, it will be the end of our island, and we should keep it stored away somewhere safe and never play it. Mum says that is rubbish. Fiddles are for playing, just as life is for living.

There is another legend about our ancestors, but it sounds so weird that not many people even talk about it, let alone believe it. They think it’s just a story that was made up to comfort the survivors, after the flood. But I’m not so sure… Maybe I believe it because Conan is my ancestor, and he was saved by a man with long hair like seaweed and the power to swim where no human being would be able to swim.

This is the legend. They say that when the wall of water swept away all those hundreds of people, not all of them drowned, even though they went down and down into the water, so far that they couldn’t rise again. A few of them – a very few – survived. Their lungs were bursting and burning for air. They couldn’t hold out against the water any longer and there wasn’t a chance of getting back to the surface. They had to breathe in.

They did breathe in. Seawater filled their lungs and salt swept through every vein in their bodies. They should have died but the sea didn’t kill them. They were filled with agony at the first breath of salt water, but then they took a second breath, and a third. Each time, their breathing grew easier. Their bodies took in the sea and became part of the sea, and they didn’t die.

It’s only a legend. Nobody ever saw one of those people who had been changed so that they could live in the sea. They could never come back, because they belonged to the sea now. Their skin changed until it looked like the skin of a seal, not the skin of a human being. They could swim as far and as fast as dolphins. They had their own language, and their own world.

Once Jago Faraday was out in his boat, night-fishing, over the place where the drowned city is said to be. It was a calm night and the sea was flat. There wasn’t a breath of wind. Jago dropped his anchor, and as he did so he looked down into the depths of the water. He saw shadows moving far below the surface.

“Shoal of mackerel, most likely,” said the men in the pub, as he told his story.

“Shoal of mackerel never looked like that,” Jago answered.

“A seal then.”

“Think I don’t know a seal when I see him?”

“Maybe it was that good old Tribute you been drinking, Jago.”

Jago scowled even more.

“I was stone-cold sober as I stand now,” he growled. “I saw shadows and I heard music. Had to turn on the engine so I wouldn’t hear it no more.”

“Don’t you like music then, Jago?” they teased him.

“Music like that, it pulls you after it,” said Jago, and he was dead serious. “You got to stop your ears and make for shore, ’fore you find yourself diving down among the fishes.”

No one believed him about the shadows and the music. But I’m not so sure…

Jago doesn’t care for music. He never listens to Ynys Musyk when we’re playing – he calls it “a load of old caterwauling”, or else he says it all sounds the same to him and he can’t understand why we waste our time playing the same stuff over and over.

“Or ‘rehearsing’, as it’s known,” I whispered to Jenna, the last time he said it.

Jago glared at me. “I heard that, you vixen.”

So why would Jago make up a story about wanting to dive into the sea because he’d heard music?

I love storms, and I hate them. They are in my blood. That’s why I’m already out of the gate with the wind whipping my hair and salt spray all over my face so that I can taste it on my lips. I’ll go down to the shore—

“Morveren! Morveren! Where are you? The meal’s ready! MORVEREN!”

It’s Jenna. The wind is still pushing me, as if it knows exactly where it wants me to go. I want to go with it. I’m curious, excited and a little bit frightened too. The night of the flood is all mixed up in my mind with nearly getting caught on the causeway, as if somehow the two things are connected – and I’ve got to find out why—

But Jenna’s calling again. She’ll be scared if I don’t answer. She’ll think something’s happened to me. I can feel her thoughts as if they were my own.

“All right, Jenna! I’m coming!”

I fight the wind all the way back to our cottage, open the door and go inside.

e’ve all eaten and Mum is saying goodnight to Digory.

“Your dad’s gone for a quick one in the pub with the others,” Mum told us when she got back from rehearsal, and we thought he’d be there for a while, talking and maybe singing. But as Jenna and I are clearing the table, the door flies open and there he is.

“The lifeboat’s gone out from Penmor,” he tells us, not coming in. Rain streams off his waterproofs. Mum hears him and comes downstairs.

“What’s happened?”

“There’s a Polish cargo ship drifting off Carrack Dhu. Lost power to the engines they say.”

“Is the helicopter out from Culdrose?”

“That’s as much as I’ve heard. With the wind as it is, she’s drifting this way, on to the reef. They’ll try to get a tow on her, but—”

We stare at each other.

“We’re going to ready the boat,” says Dad.

There’s no lifeboat station on the Island. Dad means the fishing boat he has a share in, along with Josh Matthews and Will Trebetherick.

“Where’s the sense in that?” cries Mum. “If the Penmor lifeboat’s already gone out?”

“It’ll need more than one lifeboat, if the ship breaks up on the reef. There’ll be men in the water.”

We all know how many ships have broken up on the reef. The sea around the coast here is full of wrecks. Dad knows the sea like the back of his hand. If we lived on the mainland he’d be in the lifeboat for sure.

“I’ll help you, Dad,” I say.

At that moment the gate bangs open. It’s Josh, streaming wet as well and out of breath.

“Been a message to the pub, she’s on the reef with the sea going over her. Crew got off in the lifeboat but two, maybe three, were thrown in the water. Come on.”

“Is the lifeboat still out there?” shouts Mum.

“She’s coming in. Sennen lifeboat’s on its way too. The Sea King’s had to turn back to Culdrose, technical problem.”

Everybody’s heading for the shore. The reef is a mile east of us and we’re the nearest landfall. Even though it’s dark, we can see all too clearly in our minds the way the sea will be boiling around the reef, ready to swallow ships and human lives. The wind is a hard south-westerly, maybe severe storm by now. Dad mustn’t go out in that.

But they are readying the boat.

Suddenly there is a shout. “Lights! Lights!”

It could be the Penmor lifeboat, or maybe the ship itself. The lights are close to where the reef is. Mum’s hand digs into my shoulder. The light disappears behind mountainous waves, then we see it again.

“I’m going to climb up the Mound!” I say. I’ll be able to see more from there.

“No,” says Mum, “You and Jenna come with me. We’ll get the hall ready.”

I know what she means, because it’s happened before. When I was ten, the lifeboat had to bring the rescued crew of a coaster in to the Island because the wind and tide made it too dangerous to cross the channel to the mainland. We laid out airbeds and blankets in the village hall, and gave them food and drink. As soon as the weather eased, a Sea King took a man with a broken leg to hospital. It’s happened other times too, but I was younger then and I don’t remember them.

Mum and Jenna and I get the tea-urn going, turn on the heating and blow up airbeds with pumps. Dr Kemp’s here too, setting up. Other people are in the hall, getting things ready, finding tea and sugar and mugs. Maybe none of this will be needed. I don’t want to be here, I want to be down at the harbour, watching out to sea.

“Dad won’t go out in this, will he?”

“Not unless he judges it’s right. He won’t risk giving the lifeboat any more work, you can be sure of that, Morveren.” Mum speaks calmly, but her face is creased with anxiety. She knows, as I do, that if Dad and Josh think there are men struggling for their lives out in that water, they’ll go to their rescue come what may.

“Jenna, they don’t need us here any more,” I whisper. “Let’s go back down.”

Jenna gives Mum an anxious look, but she comes with me. The wind hits us as soon as we are out of the hall. We run against it, and it holds us up like a wall of air. There’s the harbour, and for a panicky moment I can’t see Dad’s boat.

“Dad’s gone out!”

“No, look, there he is,” pants Jenna, and sure enough, there is Dad among the crowd.

“Are you OK, Dad?”

He shrugs. “Couldn’t get her out. We tried twice, nearly went over as soon as we got beyond the harbour wall.”

“Bad enough job getting her back,” confirms Josh, who is standing beside him. But they look crushed.

“Could’ve done it if we had more horse-power,” says Dad.

Everyone is out, lining the harbour, staring out to sea. Rain drives in our faces but no one seems to notice. There are two tractors with tarpaulin-covered trailers on the wharf, and I wonder why they’re there.

“There’s the light!”

It’s coming closer. A single, powerful beam that shines out and then vanishes as the boat bucks through the waves. Every time it disappears I hold my breath. Every time, it reappears. The seas are mountains that the boat has to climb.

“He’ll be getting his bearings from the harbour lights,” says Dad. “He’ll bring her round and get her in with the wind following.”

I think of the coxswain, who’s got to line up the harbour lights correctly to find the deep-water channel. It’s so easy to get it wrong. I’ve been out night-fishing with Dad and I know what it’s like to watch for those lights while your boat dips on the swell. And that’s on a calm night, nothing like this…

“Wind’s easing off a little now,” says Josh. Easing from severe storm to storm, maybe. Maybe just that little bit will make the difference and help them to bring the lifeboat safely in. Two, maybe three, were thrown in the water. How could anyone survive in a sea like this?

“Here she comes!”

I peer through the dark and wet and the thrashing water at the harbour mouth. Yes, there’s the light! The lifeboat hangs almost vertical, slides down a wave then disappears under the foam. But she’s there. She’s coming in. People are running along the harbour wall to the steps, and suddenly it is over. The lifeboat has made it. She is in the rough, safe waters of the harbour.

There are four crew from the cargo ship, and six from the lifeboat. The Polish crew are wrapped in silver survival blankets, huddled together. Dad goes down the steps behind Dr Kemp but I wait at the top so as not to get in the way. I can hear them shouting above the noise of the storm.

“Two men missing,” shouts one of the men in the lifeboat, “Sennen lifeboat’s there searching. We’re going back out.”

“Any injuries?” asks Dr Kemp.

“One broken arm, this man here. Cuts and bruises, they’re cold but they haven’t been in the water.”

“OK, I’ll see to them and be in touch with Treliske.”

Dad helps one of the Polish men up the steps. The man stumbles, and as soon as they’re up on the level Josh comes round to his other side. They half-carry the survivor over to the tractors. Now I see what they’re for. The tarpaulin is pulled back and the man is lifted very gently – I think he must be the one with the broken arm. They settle him on cushions and wrap him round with more blankets and the tarpaulin again. The tractor sets off immediately for the hall, while the second tractor waits for the other survivors. Already, the lifeboat has turned and is plunging back out to sea.

“That reef’s a desperate place on a night like this,” says a voice behind me. Jago.

“Poorish,” says Will Trebetherick, and it sounds like a rebuke. You don’t use words like “desperate” when a rescue’s going on.

Dad comes back. “We’ll start the shore search at first light,” he says. People gather round to parcel out the Island’s coast and make sure that not a metre of it goes unchecked.

Jenna’s already returned to the hall to find Mum and see if she can help there, and I follow her. Dr Kemp is with the man whose arm is broken. The other survivors stare ahead, as if they don’t yet realise that they are here, on dry land, and not plunging up and down on the sea. They are still wrapped in their silver blankets. Mrs Pascoe, who’s a nurse and works on the mainland, is chatting to them quietly as she takes pulses and blood pressures and checks temperatures. I feel as if we shouldn’t be here any more. They’ve lost so much: their ship, their friends, and very nearly their own lives. They don’t need people looking at them. I slip out of the hall.

Josh is right, the wind is easing off. Too late for the ship and maybe too late for the men who are missing. Could anyone survive out there long enough for the lifeboat to pick them up? I know the lifeboats won’t give up until they are sure there’s no more hope. Maybe the men will be found.

Dad said we would go out and search the shore at first light. I’m going too.

I don’t think I’ve been asleep, but suddenly there is grey light at the window. The shutters are open. Jenna and I didn’t want to close them last night. It seemed wrong, somehow, while the two men might be out there. Jenna’s asleep, flung out across her bed with her hair tangled. She looks pale and tired, and I don’t think I should wake her. I pull on my jeans and a hoodie, and creep downstairs. Dad is at the kitchen table, with his head propped up on his hands, drinking coffee.

“They picked up one of them,” he says without looking up.

“What about the other?”

Dad looks up. “Oh, it’s you, love. I thought it was your mother. No. No sign of him. We’ll search, but…”

I understand what he means. We’ll search the shoreline, metre by metre, but what we’re looking for may not be a living man.

“I’m sorry, Dad.”

“If me and Josh could have got the boat out…”

I say nothing. I’m glad they didn’t. It’s a fishing boat, and although it’s strong enough, it’s not made for search and rescue in seas like the ones last night. What if he and Josh had been lost, like that Polish crewman? I don’t even know the crewman’s name. It seems wrong, that someone may have died so close to here last night, and we don’t know his name.

“They don’t speak much English,” Dad says. “It’ll take a while to find out what happened. Right, I’m on my way.”

“I’ll come with you, Dad.”

“I’m not sure you should, my girl.”

“I’ll come with you.”

t’s the full light of day now, early afternoon and the tide is falling. We have searched and searched since dawn, and found nothing. A Sea King from Culdrose has been out searching too. Everybody on the Island has been out, along with coastguard services from the mainland. They came across in their jeeps when it was still dark, at this morning’s low tide. A section of the causeway has been damaged by the storm, they said. It’s still so rough that no boats are running.

I’m cold, tired and aching. I went home with Jenna at midday and we heated up some of last night’s stew, but I couldn’t eat more than a couple of spoonfuls. There was a knot in my stomach that stopped me swallowing.

Jenna stayed at home with Digory, because he was too tired to walk any farther, but I wanted to go back out. I don’t really know why. All the hope of the search has seeped out of me. My hands are sore from scrambling up and down rocks, searching in gullies and overhangs. The wind is still strong, but there are rags of blue sky now, and the barometer’s rising.

The only place we haven’t been able to search yet is the caves below Golant cliffs. They’re accessible for a couple of hours at low tide, if you go round the point. I’m glad that the Pascoe boys have volunteered for that. Those caves always give me a bad feeling. They’re dark and dripping with water, and when we were little we believed that a sea-monster lived in them. I think it was the smell of the place: fish, and something rotting out of sight.

“It’s the monster’s lair,” Jenna would whisper, and we’d scream and run out again. There are tunnels at the back, but they don’t lead anywhere. They are just waiting to wrap themselves around you as the tide rises to fill them to the roof.

I’ll stop soon, and go back home for a while to warm up. No one really believes that we’ll find the missing man alive now. Too many hours have passed. I hope he died quickly. I hope he didn’t struggle too long in the water, hoping for rescue which didn’t come. I hope he wasn’t trapped anywhere. That’s my worst nightmare.

I rub my hands together to warm them. The sun is out now, sparkling on the waves. It looks so beautiful that it’s hard to believe this is the same sea that drove a cargo ship on to the reef last night. The wind is still cold, though. I shield my eyes and stare down the stretch of pale sand, to the rocks that gash into the water. Porth Gwyn. That’s its proper name but we just call it “the beach” because it’s where we always played when we were little. In the summer people come out here to sunbathe. It’s not a great place to swim because of the rips, but there’s a big natural pool hidden among the rocks, right down at the end of the beach. It’s more than two metres deep at one end. Jen and I call it King Ragworm Pool because we found the biggest King Ragworm we’ve ever seen in it, after a storm. It was half a metre long, and hideous. It put us off swimming there for a long time.

The pool fills from a channel, because the tide doesn’t come up far enough. It’s quite strange how it happens: there’s another rock pool higher and closer to the sea, which fills with every tide, and then the water runs to King Ragworm Pool. It looks as if someone engineered a channel long ago.

I search among the rocks, peering down into deep clefts and gullies where the sea thumps in at high tide. While I’m looking, I don’t let myself think about what I’m looking for. I think about Jenna and I searching for lost things that the tide has taken. If you’re patient, and thorough, you often find them. Maybe I should check again along the surf and the shoreline.

At that moment the church bell rings out from the village. Even at this distance I can hear it clearly. Just one bell, tolling out one slow stroke, and then another, as they do for a funeral. It’s a signal. The wind lifts the sound, carries it towards me and then snatches it away. I know exactly what it means. At times like these the church bells have their own language, and everyone understands it. The lost man has been found, but he is dead. If they’d found him alive, all the bells would have pealed out a clangour like wedding bells. This single bell-note is telling us it’s time to give up, and come home.

Such a slow, heavy sound. The sea glitters as the sun comes out more strongly, and a gull dives down, screeching. They used to say gulls were soul-birds, and carried the souls of drowned sailors. No one believes that now, but I wish it were true as I watch the gull ride the waves of the air.

Five men were saved, I remind myself. The lifeboat did everything it could.

I ought to go back home, but I don’t want to. Everybody will be talking about where the man’s body was found.

I wander slowly along the strand, still watching the gull which has now soared high into the air. It heads out to sea and soon it is out of sight. Maybe you’ve gone back to Poland, I think, but I can’t really believe it. The bell is still tolling.

The rocks ahead of me are covered with mussels. Maybe I’ll pick some. Tide’s way out now. The Pascoe boys will be able to get round to the caves at the base of Golant cliffs. Then I remember that there’s no need for them to do that any more.

Anyway, it was a stupid idea to pick mussels, because I’ve nothing to carry them in. Mum usually has an “in case” bag in her coat pocket. I dig my hands into my waterproof pockets, and to my amazement I pull out a Sainsbury’s bag. Where did that come from? I remember that it’s from when Jen and I bought Cokes and crisps in Marazance. I must have stuffed it in my pocket afterwards. Obviously I am meant to pick mussels.

I’m walking towards the rocks when I hear it. Not the bell, but something much closer. A sound like a groan, quickly smothered. I stop, and stare all around. Nothing. Empty sand and empty sea. But I’m sure I heard it. I wait, dead still. Seconds tick past, with the wind soughing in my ears, and the sand sifting underfoot. Nothing. I’m about to walk on when it comes again. The kind of sound you make when you’re in too much pain to keep quiet, but you choke it back as soon as you can, because you’re frightened of people hearing. But who would be frightened of me?

“Who’s there?” I call. No one answers. My mind races. Maybe there was another crewman, and in the confusion of the wreck he was forgotten. Or else, maybe the rescued crewmen gave the number of crew wrong. They barely speak English. What if there’s another man, an injured survivor lying somewhere close, maybe unconscious? You can still groan when you’re unconscious, I think. I’ve got to find him.

“Where are you?” I call. “Don’t be frightened. I want to help you.”

Even if he doesn’t understand English, surely he’ll realise that my voice is friendly.

“Call out again if you can. I’ll find you.”

Nothing. I don’t know what’s best to do. Should I run back to the village and fetch help? No, it’ll waste time. If he’s been lying out all night he’ll be suffering from exposure even if he isn’t injured. If I find him I can wrap him up in my hoodie and waterproof and then go for help. It’s a miracle he’s still alive.

“I’m coming!” I call again. “Don’t be frightened!”

I run forward until I reach the rocks. I don’t think the groan came from here but the best way is to search backwards methodically, from the tide-line to the dunes. The sand here isn’t clean and shining. It’s covered in bits of wood, seaweed, twine, a dead mackerel and a tangle of weed and crab legs. The flotsam and jetsam spreads all the way up the beach here, and right over the dunes which are anchored with tough marram grass. The sea’s come up much higher than normal. Maybe the storm produced freak waves.

Suddenly the skin on the back of my neck prickles. I have an overwhelming feeling that I am not alone. Someone is watching me. I turn quickly, but the beach and the dunes are empty. I turn back to the rocks, and scan along them. Nothing. But my back still prickles. Very slowly and casually, I bend forward and kneel down as if I’ve spotted something in the sand. I’ve plaited my hair because of the wind, and the plait falls forward. Cautiously, I peep round. Even if someone’s watching, they won’t notice because my thick plait hides my face. I shuffle round a little way on my knees, and pretend to be digging. Whoever is watching will be off-guard by now. They will think I’m concentrating all my attention on what is in front of me. I am quite sure now that there is someone there. My heart is thudding. I want to leap to my feet and race for home, but I can’t. If there’s an injured man lying there, then he must be even more frightened than I am. That’s why he’s hiding. Maybe he’s had a bang on the head when the ship went on the reef, and he thinks he’s in an enemy country or something. Me shouting out in a foreign language won’t help.

I turn my head a fraction, still looking down. I shake my plait right forward so there’s a gap between it and my shoulder, and, very stealthily, I steal a glance behind me.

Yes. A movement. A tiny flicker of movement behind the dunes. Maybe a hand, or the side of a face. There is someone there and whoever it is must be very scared. He knows I’m here and he’s in pain or he wouldn’t have groaned like that. But he won’t call back to me. That means he is much more afraid than I am.

I think for a moment, and then very slowly I get up and brush the sand off my hands and the knees of my jeans. I take the plastic bag out of my pocket and pretend to put something in it. I slip the bag into my pocket, shield my eyes and stare straight ahead, towards the rocks. After a while I shrug my shoulders, as if I’ve given up looking. Maybe I don’t believe I heard anything. It must have been my imagination. I hope that my body language is saying these things to the watcher behind the dunes. With luck he’ll relax, reassured, and sink back into his hiding-place.

I take a careful note of where the movement was, and how far down the beach I need to walk to be parallel to it. I stroll casually along the sand, stopping once or twice to pick up a tiny shell, and put it into my pocket. All I am is a girl out for a walk on the shore.

I am parallel to the spot in the dunes now. I slide my gaze sideways for a second. No sign of life. I walk forward a little more. He won’t be able to see me now, because the bulk of the dune will hide me from him just as it hides him from me.

Suddenly, I change direction. My feet make no sound in the soft sand as I run to the dunes, scramble up the sifting slope, and over the top.

he first thing I see is an arm drawn back, a fist, and a stone in the fist, ready to throw. I see dark, glittering eyes and a tangle of hair like seaweed. I hold my own hands out, palm up.

“I won’t hurt you,” I say, and drop to my knees, keeping a distance. Surely he’ll see that I am not a threat.

Slowly, slowly, the hand gripping the stone relaxes. Even more slowly, he lowers his arm.

“Who are you?” I ask, keeping my voice soft and level, but then I remember that he probably doesn’t speak any English. His shirt and jacket must have been torn off in the struggle with the sea. He’s half-buried in sand, but I can see his bare arms and shoulders, in fact most of his body down to his waist. He is surrounded by flotsam and jetsam. Suddenly I realise what must have happened. There was a freak wave. It must have lifted him, hurled him over the beach and the dune, and half-buried him in the sand. He’ll be freezing cold. It’s amazing that he hasn’t died of hypothermia.

“It’s all right,” I say again, “I’m a friend. I want to help you.” Then I have an idea. I point to myself and say, “Mor-ver-en,” very slowly. Gradually, so as not to alarm him, I shuffle forward. His eyes stay fixed on my face. He doesn’t seem to blink. I don’t think I’ve ever seen such glittering eyes. His skin is a strange colour: it’s brown, even darker brown than mine, but it has a blue tinge to it that I’ve never seen before. It scares me. I think he must be badly hurt, or maybe blue with cold.

He struggles to move as I come closer, as if he wants to get away, but the movement ends in a groan. I stop dead. He’s definitely injured.

“It’s all right. I won’t come any closer. Please don’t be frightened of me.”

He looks young. I don’t think he’s a man, he’s only a year or so older than I am. Do they have crew that age on Polish ships? He could be a passenger, the son of the captain maybe. Then I see something that really scares me. The sand around where his legs must be buried is rusty brown. He’s bleeding. The stain on the sand is wide. He must have bled for hours.

I glance round desperately. I’ll have to leave him and run for help. He could bleed to death if I don’t. But what if he thinks I’m abandoning him? I’ve got to make him understand. “Listen, I’m going,” I point at myself then over the dunes, “for help. Someone to help you, you understand? A doctor.” Maybe the word for doctor is the same in Polish? He watches me intently, then suddenly puts out his hand, as if to hold me back. Or maybe he wants me to feel his pulse or something…

I reach forward, and take his hand. It is cold, but the grip is surprisingly strong. He seems to want me to come closer. I edge forward, until I’m beside him. If he’ll let me uncover his legs then I can see how badly injured he is. But probably he’s embarrassed, if the sea has torn off all his clothes.

That stain on the sand is definitely blood. The thought of seeing the wound makes me feel sick. He is still looking into my face, and this time his lips move.

“Morveren,” he says.

He’s understood! I feel warm all over with relief. “Yes! I’m Morveren.”

He lets go of my hand, and points to his own chest. “Malin,” he says.

“Your name is Malin?”

“Yes, my name is Malin,” he says, in perfect English but with an accent I don’t recognise. I’m so stunned that I drop his hand and rock back on my heels.

“You speak English!”

“Yes, I speak your language. Morveren, you must help me. You must help me to go back to the sea.”

Now I know for sure that he is very ill. Probably having delusions or whatever people get when they’ve had a blow on the head. “Don’t worry, I’m going to get help for you. You’re hurt and you need to go to hospital. Will you… Will you let me try to move the sand away, so I can see what’s happened to you?”

He frowns sharply. His eyes flash. “No! No human beings must come here! You must help me return to the sea.”

“Malin, I think you’ve got a fever, or maybe you hit your head against a rock when the wave caught you. That’s why everything seems strange to you.”

“Why are you so stupid?” he demands furiously.

“Stupid! I’m trying to help you.”

“And I am telling you how you must help me!”

I take a deep breath. Keep cool, I tell myself. You don’t argue with someone who’s been shipwrecked and nearly drowned as well as injured. He’s probably – what is the word – delirious. “I can’t take you to the sea. You’d die. You need to go to hospital.”

“Look at me,” says Malin through his teeth. “Stop talking and look at me.” His hands scrabble at his sides, trying to clear away the sand. But he’s lying in an awkward position and he can’t manage it.

“Shall I help you?”

He nods furiously, and I lean forward and begin very gently moving away the sand. I’m afraid of hurting him, and just as scared of seeing whatever injury has caused all the blood. I work slowly and methodically, clearing the sand, until suddenly my fingers touch his skin. I snatch them back. “Am I hurting you?”

He shakes his head, with his lips pressed tightly together. “Go on,” he says. Cautiously, I move away more and more sand. His skin is very dark. It’s strangely thick, almost as if he were wearing an incredibly light and flexible wetsuit, made out of some material that hasn’t been invented yet. It reminds me of something but I can’t think what. “Keep going,” says Malin, with a strange smile on his face.

“I’m scared of hurting you.”

“I am strong.”

I take no notice of this. He doesn’t look very strong at the moment. I’m afraid he’ll faint, and so I dig away the sand more gently than ever. The curve of his thigh is almost uncovered—

My hand goes to my mouth in horror as I see the deep, long gash that gapes wide, full of dried blood and still oozing. It must have bled for hours. It is clogged with sand. Malin is struggling to raise himself on his elbows in order to see the wound. But he mustn’t. He’ll start it bleeding again if he moves like that—

“Keep still,” I say sharply. “It’ll be all right. It’s going to need stitching.”

“Stitching!” Malin’s eyes widen in horror, as if I’d said, “You need to be rolled in maggots and then we’ll cut your leg off.”

“That’s why we need to get you to hospital,” I tell him. I keep on clearing away the sand, in case there are other injuries. Suddenly, Malin heaves himself up, pushes my hands away and starts to brush off sand himself. As I feared, more blood oozes from the gash, but Malin won’t stop. His hands are quick and they clear the sand much faster than mine. I don’t want to look in case the storm really has torn off all his clothes and this is going to be embarrassing…

My hands won’t move. I stare, transfixed. My brain won’t make sense out of what my eyes are telling it. The shape in front of me wavers. My ears hiss as if they have got sand in them. I close my eyes and breathe deeply. I’m going crazy. I’m the one who’s going to faint. It’s all right, I tell myself, it’s because you hardly got any sleep last night and you haven’t had anything to eat for hours. Just breathe.

After a long moment I open my eyes again. What I see is the same. Dark, strong, leathery skin. No, not leathery. Leather belongs to earth and this skin belongs to the sea. Sealskin. At last I find my voice, and it comes out in a squeak.

“Your— Your legs… What’s happened to them?”

“My legs,” repeats Malin with contempt. “My legs? Where are my legs, Morveren?”

Where are they? All I can see is a strong, curved shape. No thigh or knee or foot. Just a— just a—

A tail.

My brain whirs, still trying to make sense of what I see. It whirs but does not connect. He is a boy. He has no legs. Instead he has a—

A tail.

“Are you wearing a costume?” my voice bleats. Even as I hear the words, my brain knows how stupid they are. And so does Malin.

“Touch my skin,” he orders.

“I don’t want to hurt you.“

“Touch it.”

It is skin. I snatch my hand away as if it’s been burnt.

“Now you understand why you must help me to go back to the sea.”

“You mean… You live in the sea? You’re a mer… mer… person?”

“I am Mer,” says Malin, as if it’s the proudest claim that could be made by anyone.

“You are Mer,” I echo, as if I’ve been set to “repeat” mode. But Malin seems pleased with the answer.

“Now you understand and you will help me,” he says confidently. But the wound gapes wide. He’ll collapse if he goes back into the sea, even if he is… I try the word over in my mind. Mer. He’ll still die. One wave would roll him over on to the shore again, and strand him. Dolphins that are stranded can’t live long, because unless the sea is buoying them up, their own weight crushes their internal organs. Maybe it is the same for the Mer.

As if my thoughts have reached him, Malin sinks back against the dune and shuts his eyes. Without their glitter his face is drawn and lifeless. He must have lost a lot of blood in the night. I won’t think about him being Mer. I can think about all that later. First, I’ve got to make sure he doesn’t die.

“You really do need help, Malin,” I say softly, leaning over him. “Let me go and fetch my dad and Dr Kemp. They won’t hurt you, I promise.”

His eyes fly open. “They will take me away. They will imprison me and take away my freedom.”

“Malin, I swear they won’t. I’ve never heard of anything like that happening. Dad wouldn’t—”

“If humans catch the Mer, that is what will happen. Everyone knows it. We learn it before we can speak.”

“They won’t—“ I begin, but then I stop. How can I be so sure? Terrible things have happened to anyone – or anything – that is different. What if they put him in a tank and do experiments on him? People do experiments on animals, to find out about them. Scientists might say that Malin is an animal. A rare sea-mammal that needs to be studied in detail. They might say it’s research of national importance. Once they’d got hold of Malin, I wouldn’t be able to do anything. They’d brush me away like a fly.

“But… but you’re human! You speak English. They couldn’t do that to you,” I say, trying to convince myself as much as Malin.

“I am not human, Morveren. They will not give me the protection they give to their own kind. You kill among yourselves. Why should you not kill me?”

“I wouldn’t, Malin – we wouldn’t—” But I can’t meet his eyes. Chimpanzees look nearly human. They share most of their DNA with us. But we do research on them. We experiment on them and because they’re not quite human, that’s all right.

Maybe Malin knows that.

“I must have water,” he says, in quite a different voice, almost a groan.

“I’ll get you water! Wait here.”

“No.” He puts out his hand to stop me. “You drink water from the earth and I cannot swallow it. I must have salt. I must be in salt water if I am to live. I am strong but my skin is already cracking. Soon I will die.”

He says it calmly, as if he’s talking about someone else. For a second I think he can’t mean it, but then I look at his skin. It’s parched and seamed all over with tiny cracks. It reminds me of photos I’ve seen when there’s a drought in Australia.

But I don’t know what to do. Malin can’t move on his own. I can’t move him on my own: he’s much too heavy for me. Even if I did manage to drag him down to the sea, the waves would throw him back on land. He hasn’t the strength to swim against a rough sea.

A rough sea… It’s as if the words light a fuse in me. When the sea’s too wild for swimming, you can always swim safely in King Ragworm Pool. That’s what Jenna and I used to do. The solution comes to me, clear and perfect. Malin will be safe in King Ragworm Pool. He can rest there and recover until he’s strong enough to go back in the sea. Salt water is good for wounds. King Ragworm Pool is salt water, because it’s fed by a stone channel from the tidal pools closer to shore. Jenna will help me. We’ll bring the groundsheet and we’ll pour salt water over it so Malin’s skin doesn’t get damaged. Surely we can manage to carry him as far as the pool. We’ll have to climb the rocks but we can take it slowly.

Malin’s looking away from me again, to where the sea sounds beyond the dunes. His face is a blank. He can’t really think he’s going to die. He’d be frightened – anyone would be terrified…

“Malin, I think I know what we can do.” He turns his head languidly, as if he’s only listening out of politeness. “There’s a pool near here where you can go. It’s salt water and it’s hidden, but I’ll need help to get you there. I can’t do it on my own.”

Malin sweeps my idea aside with a flick of his hand. It’s so arrogant that I’d be really annoyed with him if he weren’t half-buried and badly hurt. “I prefer to die than have other humans here,” he says.

“I’ll get my sister. She’ll help you and she won’t say anything. I swear she won’t.”

“You swear? On what?”

I think hard and quickly. I want to swear on the most precious thing I can think of.

If that fiddle is ever lost or broken, it will be the end for our island.

“I swear on Conan’s fiddle,” I tell Malin.

“What is that?”

“It’s really old. It came to my ancestors when our city was drowned. It’s like our – I don’t know – our luck. Something we have which keeps us safe.”

Malin’s gaze sharpens. “What city was that?”

“It was on land, but there was a tidal wave or something and it disappeared. But it’s only a legend,” I add quickly, because his stare is making me uneasy.

“I would like to see that instrument,” says Malin softly, half to himself, and then he turns his head away and shuts his eyes. He seems so drowsy now, as if he’s sinking away from me, fathoms and fathoms down into the depths of an ocean where I can’t follow him.

“Mum, what’s it like to die?” I asked Mum that after our granddad died, and she said, “It’s like falling asleep, Morveren. It’s nothing to be afraid of.”

I’ve got to get Jenna quickly. Malin mustn’t fall into that sleep.

“Go then,” says Malin, in a voice so quiet that it might be the sigh of the wind.

t’s not until I burst through our cottage door that I remember about the drowned Polish sailor. Jenna’s sitting by the fire, hugging her knees and staring into the flames. Digory’s lying on the floor playing with his toy cars. Jenna looks up.

“Didn’t you hear the church bell? I thought you’d come straight back.”

“Yes – but Jenna—”

“He still had his life-jacket on. The helicopter spotted him. They might have found him in time, if it’d been daylight.”

Jenna turns to me, her face pale and upset. I know she’s thinking the same as I am. How long did the sailor survive, hoping for rescue?

“He was called Adam,” says Jenna. “One of the other men told Mum. It’s better knowing his name, don’t you think?”

“Yes. But Jenna—”

“Don’t you want to talk about it?” says Jenna, with a rare flash of anger.

I look at her over Digory’s head. He’s humming to himself, telling himself a story about his cars, but that doesn’t guarantee that he’s not listening.

“I need your help with my maths,” I say.

Instantly, Jenna’s face sharpens. It’s a signal we use whenever we need to talk to each other urgently but don’t want anyone else to know.

“I’m just going up to our bedroom with Morveren, to look at our homework,” she tells Digory, who nods without stopping his game.

Upstairs, Jenna shuts the door before asking, “What’s wrong?”

“Jen, you’re not going to believe this, but please, please listen before you say anything. Promise?”

She nods, and folds her arms. I know she thinks I’ve done something awful and she’ll have to cover up for me.

Jenna is good at listening. Even now, when I’m telling her something that no one in their right mind could possibly believe, she listens attentively, frowning a little. I tell her about the noise I heard, and about finding Malin, and how he’s hurt and needs help. When I tell her about how I uncovered the sand and saw his tail, I see the pupils of her eyes widen, but she still says nothing.

“He needs us to help him, Jen. We’ve got to get him into the water.”

Jenna remains silent.

“Don’t you believe me?”

Very slowly, she nods. “I believe that you believe it,” she says.

“But it’s true!”

“Morveren, when you were climbing on the rocks, do you think you could have slipped? Is there anything you can’t remember?”

She thinks I fell and banged my head, and I’ve imagined everything because I’m concussed or something. It’s what anyone would think, but Jenna’s my twin sister. She must be able to see that I’m deadly serious. I want to shake her to make her believe me. But would I have believed in Malin, if I hadn’t seen him and touched his skin? Mer people don’t exist except in stories, everybody knows that.

“Jen, listen. I didn’t bang my head, I swear. Even if you don’t believe me, just come. If there’s nothing – I mean, if he’s not real – then it won’t do any harm, will it? But he’ll die if we don’t help him.”

Jenna shivers, and rubs her arms. “It’s been such a horrible day,” she says very quietly, as if she’s talking to herself. “I wish it was over. I can’t leave Digory on his own, Mor.”

“He’ll be fine! He likes being on his own.”

It’s true. Digory’s one of these people who’s happy just being himself. I can see that Jenna’s wavering. She still doesn’t believe me, but she can sense how desperate I am.

“I’m going to get the groundsheet so we can carry him to the pool.”

“It’s under the stairs,” says Jenna automatically. She always knows where things are.

I go to fetch the groundsheet, and Jenna comes after me.

“You don’t have to follow me,” I snap. “I’m not going to collapse, even though you don’t believe I didn’t bang my head.”

“All right then, I’ll come with you,” she says suddenly. Her face is creased with worry. “I’m not letting you go on your own.”

She hooks the fireguard to the wall and tells Digory to be sure and not touch it. Mum is working a few hours at the post office, and if he needs her he can run down there. Dad’s at the harbour. “Just play, Digory. Don’t go in the kitchen and don’t touch the fire. Do you understand? If you’re really good, I’ll give you a surprise when we get back.”

“What surprise?” asks Digory. Jenna glances at me and says, “Morveren’s Mars bar that she’s hidden in the freezer.”

“Jen!”

“Surely it’s worth a Mars bar?” asks Jenna coolly, and I have to shrug and agree.

“I’ll be really good, Jenna,” says Digory earnestly.

Once we’re clear of the village I start to run. I’m so scared that Malin will die before we get him into the water. It’s like a stone in my stomach. People do die. That man last night… Adam. He was waiting for help and it didn’t come.

“He’s right down the end,” I pant.

The beach looks completely empty, and for a moment even I doubt everything. Jenna stares ahead, her face carefully inexpressive, but I know what she’s thinking.

“We need to go down to the rocks, then I can get my bearings. We have to find the right dune.”

I run down the beach, with Jenna following. I look around, trying to fit the landscape into the right pattern. Not here. I go on. I think this is where I was when I first heard Malin groan, but I’m too far down the beach. I turn and start to walk backwards in the direction we’ve come, looking left, then right, then ahead. I glance behind me. Was it here? No, it’s still not quite right. Why didn’t I check Malin’s exact position before rushing off for help? All the dunes look the same. Was it that one – or that one? Jenna watches me, saying nothing.

“It was definitely around here,” I say, and set off towards the dunes. We scramble up, grabbing hold of the tough marram grass to help us keep our balance in the shifting sand. We are at the top.

There’s nothing. Jenna comes up beside me, and stares around at the empty curves and hollows of the dune. Still, she doesn’t speak.

“It must have been further down.” I am hot all over now from nervous fear, and the weight of the groundsheet. Any minute, Jenna will say she’s going back home. I skid down the side of the dune again and Jenna follows. Back on the flat sand, I look out to sea and then at the rocks, trying to get my bearings again. It still doesn’t look right. I walk backwards.

Suddenly sea and rock and sand slide into place, as if I’ve put in the last piece of a jigsaw puzzle.

“This is the place! I know it’s here!”

Jenna nods but I see scepticism in her face. She’ll humour me a bit longer. Again, we climb the side of the dune. There’s the top, exactly as I remember it. I climb up, and stand stock-still, my heart beating hard with relief and also with… Well, with disbelief. It is all true and there must have been a part of me that still didn’t quite believe that it could be true. I didn’t bang my head. Against all the laws of reality, Malin is real. There he is, lying in the hollow of the dunes, eyes closed, head flung back, as if—

“Jenna! Quick! Quick!”

Jenna scrambles up, panting, and then she sees him. She grabs hold of me, digging her nails into my arm.

“Let go, Jenna!”

In a second I’m at Malin’s side.

“Malin! Malin!”

Very slowly, his eyelids part. My heart thuds so hard I have to swallow in order to speak.

“My sister’s here, Malin,” I say, as calmly as I can. You’ve got to be calm with people when they’re really ill. “You’re going to be all right. We’re taking you to the salt water.”

But I can see from his face that there’s not a moment to lose.

“Let’s get the groundsheet out flat beside him, then we can lift him on to it. We haven’t got time to wet it. Come on, Jen!”

Jenna looks as if someone’s hit her in the face, she’s so shocked.

“Jenna, help me!”

Her hands are shaking, but she helps me to spread out the groundsheet.

“I’m going to go round behind him and get my hands under his arms. You lift under his— his tail.”

“Do you think we ought to move him?”

“We’ve got to. He’ll die if we don’t.” Jenna is so pale I’m afraid she’s going to faint.

“Then we can wrap the groundsheet round him and carry him to the pool. He was talking to me before. He speaks English.”

With a huge effort, Jenna collects herself. “King Ragworm Pool, you mean?”

“Yes.”

“But we’ll have to get him up the rocks.”

“We can do it.”

Lifting Malin on to the groundsheet is the worst part. The first time we try to lift him, he slips and his tail hits the ground. He groans and the colour ebbs from his face, leaving it a dirty grey-blue. I’m afraid we’re murdering him, not helping him.

“Try kneeling at right angles to his body, Jen. Get your arms right under him.”

She’s in position. I tighten my grip under Malin’s arms.

“One, two, three – lift.”

This time it works. We lift Malin as gently as we can, and lay him on the groundsheet. He’s heavy. Carefully, we wrap the groundsheet around him like a sling, so he can’t fall out. The gash in his tail is bleeding again, but not too badly. We decide Jenna will walk backwards, holding his tail, and I’ll keep hold of him under the arms, through the groundsheet, so he can’t slide out of it.

It is a nightmare journey. Getting him off the dunes is the worst part, because we are so scared of losing our balance and falling with him. I dig my heels into the sand for balance and try to take his weight as Jenna feels her way carefully back downwards.

By the time we’re on the flat sand I’m sweating all over. Jenna’s hair sticks to her forehead.

“Wait, he’s slipping.”

We get a firm grip again, and set off slowly, painfully, across the sand. It feels so exposed. What if someone sees us? They’ll think we are burying a body. Malin groans again as the groundsheet jerks. Oh no, we’re hurting him. We’re making things worse. I should have told Dad and Dr Kemp and let them help us—

No. He wanted me to get him to the water. He didn’t want anyone else to know. We’re doing what he asked.

It seems to take hours to reach the rocks. They’re not very high, but they loom over us like mountains now that we’ve got to get Malin up them. It’s so easy to climb up there usually that I hadn’t realised how difficult it would be with the dead weight of Malin between us.

“Let’s work it out logically,” says Jenna, wiping her hair away from her eyes. Her voice is shaky but it’s her sensible, “Jenna-solving-a-maths-problem” voice. What’s logical about any of this? I think, but I say nothing.

“We need to keep his head higher than his body,” she goes on. “It’s probably safest to go up side by side, don’t you think?”

“OK.”

“There’s a ledge for you there – and I can dig my foot in sideways, into that cranny. Let’s get up there first then work out the next foothold.”

Jenna’s in full practical mode now. Whether or not Malin is real, there’s a job to be done and we’re here to do it.

We daren’t risk falling with Malin, so we test each foothold over and over before we lift him. We only have to climb about ten feet, but the rocks are razor-sharp. If we dropped him…