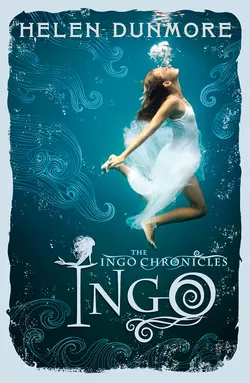

Ingo

Helen Dunmore

A spellbinding magical adventure. Master storyteller Helen Dunmore writes the story of Sapphire and her brother Conor, and their discovery of INGO, a powerful and exciting world under the sea.You’ll find the mermaid of Zennor inside Zennor church. She fell in love with a human, but she was a Mer creature and so she couldn’t come to live with him up in the dry air. She swam up the stream to hear him sing, then one day he swam down it and was never seen again. He became one of the Mer people…Sapphire’s father told her that story when she was little. When he is lost at sea she can’t help but think of that old myth; she’s convinced he’s still alive.The following summer her brother Conor keeps disappearing for hours on end. She goes to the cove to find him, but instead meets Faro, an enigmatic and intriguing Merman. He takes her to Ingo and introduces her to a world she never knew existed. She must let go of all her Air thoughts and embrace the sea and all things Mer.After her first visit she is entranced – merely the sound of running water makes her yearn to be in Ingo once more. Ingo blood runs strongly in Sapphy and Conor fears she will leave the Air world for good. He pleads with her to ignore her craving for the sea and stay safely in their cottage up on the cliff.But not only is Sapphy intoxicated by the Mer world, she longs to see her father once more. And she’s sure she can hear him singing across the water…“I wish I was away in IngoFar across the briny sea…”

INGO

by

Helen Dunmore

COPYRIGHT (#ulink_b719b6e6-8159-5089-b582-8df561ab6a75)

HarperCollins Children’s Books An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd. 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk/)

First published in hardback by HarperCollins Children’s Books 2005 First published in paperback by HarperCollins Children’s Books 2006

Copyright © Helen Dunmore 2005

Helen Dunmore asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue record for this book is available at the British Library.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins ebooks

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication

Source ISBN: 9780007464104

Ebook Edition © AUGUST 2012 ISBN: 9780007381371

Version: 2017-03-28

PRAISE (#ulink_68c1fdbd-81fb-5412-bf18-9f53a8529386)

“The electric thrill of swimming with dolphins, of racing along currents, and of leaving the world of reason and caution behind are described with glorious intensity.” Amanda Craig, The Times

“Compellingly lyrical.” Independent

“Helen Dunmore may have a few drowned readers on her conscience, so enticing and believable is the underwater world she creates in Ingo.” Telegraph

“Helen Dunmore is an exceptional and versatile writer and she writes with a restrained, sensual grace.” Observer

“A remarkable fantasy… It’s a haunting, beautifully written book which creates a totally believable parallel world.” Northern Echo

“Ingo is an intoxicating adventure… Wonderful, evocative storytelling.” Publishing News

“As ever, Dunmore’s characters are beautifully drawn… Though the first in a series, this book works perfectly as a standalone title, with a satisfying resolution but enough left hanging in the air to make the characters and situations live on in the reader’s mind. Ingo has a haunting, dangerous beauty all of its own.” Philip Ardagh, Guardian

DEDICATION (#u1d55340e-7328-580a-bcc9-73b96be0bfd7)

FOR TESS

CONTENTS

Cover (#u7f8a8cd9-4833-5f79-9513-ea44a11e798d)

Title Page (#u1f081881-3526-5674-a3d9-05edf833fcab)

Copyright (#uf8b15f87-3588-59db-b7d6-9df1d0257a53)

Praise (#u5d2e913e-ceb6-5422-89f1-4f7645691dd9)

Dedication

Chapter One (#ua89c6621-c8e8-56a8-8271-8b59c156bc57)

Chapter Two (#ud7f837d2-7ea5-54b1-a743-20e7e87b4cbf)

Chapter Three (#uc826be4b-ff99-5360-95c7-9b8cbb4e6a6e)

Chapter Four (#u2b572352-afe5-5ea3-90b5-3fb1af476c06)

Chapter Five (#u0efb1d34-d6e6-5091-a55a-14aabd04533c)

Chapter Six (#ud1beac39-6b3e-51db-b8b9-daa914fc2cf0)

Chapter Seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Ten (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eleven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twelve (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fourteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Sixteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seventeen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eighteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nineteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-One (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Two (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Three (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Four (#litres_trial_promo)

Keep Reading (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

In this Series (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER ONE (#ulink_125c66db-99ba-530f-88ef-6763534c3f7d)

You’ll find the mermaid of Zennor inside Zennor Church, if you know where to look. She’s carved from old, hard, dark wood. The church is dark, too, so you have to bend down to see her clearly. You can trace the shape of her tail with your finger.

Someone slashed across her with a knife a long time ago. A sharp, angry knife. I touched the slash mark very gently, so I wouldn’t hurt the mermaid any more.

“Why did they do that to her, Dad? Why did they hurt her?”

“I don’t know, Sapphy. People do cruel things sometimes, when they’re angry.”

And then Dad told me the mermaid’s story. I was only little, but I remember every word.

“The Zennor mermaid fell in love with a human,” said Dad, “but she was a Mer creature and so she couldn’t come to live with him up in the dry air. It would have killed her. But she couldn’t forget him, and she couldn’t live without him. She couldn’t even sleep for thinking about him. All she wanted was to be with him.”

“Would she have died in the air?” I asked.

“Yes. Mer people can’t live away from the water. Anyway, the man couldn’t forget her either. The sight of the mermaid burned in his mind, day and night. And the mermaid felt just the same. When the tide was high, she would swim up into the cove, then up the stream, as close as she could to the church, to hear him singing in the choir.”

“I thought it was mermaids that sang, Dad.”

“In this story it was the man who sang. In the end the mermaid swam up the stream one last time and he couldn’t bear to see her go. He swam away with her, and he was never seen again. He became one of the Mer people.”

“What was his name, Dad?”

“Mathew Trewhella,” said Dad, looking down at me.

“But Dad, that’s your name! How come he’s got the same name as you?”

“It’s just by chance, Sapphy. It all happened hundreds of years ago. You know how the same names keep on going in Cornwall.”

“What was the mermaid called, Dad?”

“She was called Morveren. People said she was the Mer King’s daughter, but I don’t believe that’s true.”

“Why not?”

“Because the Mer don’t have kings.”

Dad sounded so sure about this that I didn’t ask him how he knew. When you’re little, you think your mum and dad know everything. I wasn’t surprised that Dad knew so much about the Mer.

I stroked the wooden mermaid again, and wished I could see her in real life, swimming up the stream with her beautiful shining tail. And then another thought hit me.

“But Dad, what about all the people the man left behind? What about his family?”

“He never saw them again,” said Dad.

“Not even his mum or his dad?”

“No. None of them. He belonged to the Mer.”

I tried to imagine what it would be like never to see Dad again, or Mum. The thought was enough to make my heart beat fast with terror. I couldn’t live without them, I knew I couldn’t.

I looked up at Dad. His face looked faraway and a bit unhappy. I didn’t like it. I wanted to bring him back to me, now.

“Can’t catch me!” I shouted, and I ran off clattering up the stone aisle of the church to the door. The door was heavy and the fastening was stiff but I wrestled it open.

“You can’t catch me!” I yelled back over my shoulder, and I ran out through the porch, down the stone steps and into the sunshine of the lane. I heard the church door bang and there was Dad, leaping down the steps after me. The faraway look had gone from his face.

“Look out, Sapphy, I’m coming to get you!”

That was a long time ago. Dad never talked about the Mer again, and nor did I. But the story lodged deep inside my mind like an underwater rock that can tear a ship open in bad weather. I wished I’d never seen the Zennor mermaid. She was beautiful, but she scared me.

It’s Midsummer Eve now, and when it gets dark they’ll light the Midsummer Fire on Carrack Down. We go up there every Midsummer Eve. I love it when they throw the wreath of flowers into the flames, and the wreath flares up so that for a few seconds you watch flowers made out of fire. The bonfire blazes and everyone drinks and dances and laughs and talks. Midsummer Night is so short that dawn arrives before the party’s over.

Dad’s up there now, helping build the fire. They pile furze and brushwood until the bonfire stands taller than me or Conor. Conor’s my brother; he’s two years older than me.

“Come on, Saph! I’m going on up to see how big the bonfire is now.”

I run after Conor. This is how it usually is. Conor ahead, and me hurrying behind, trying to keep up with him.

“Wait for me, Con!”

We wait for the sun to set and for the crowd to gather, and then it’s time to light the Midsummer Fire. The first star shines out. Geoff Treyarnon thrusts his flaming torch into the dry heart of the bonfire. The fire blazes up and everyone links hands and begins to dance around it, faster and faster. The flames leap higher than the people and we have to jump back.

Conor and I join the ring around the fire. Mum and Dad dance too, holding hands. It makes me so happy to see them like this, dancing and smiling at each other. If only it was always like this. No quarrels, no loud voices…

The flames jump higher and higher and everyone yells and laughs. Conor drinks a bottle of ginger beer, but I don’t like the taste. I wrap myself in a rug and sit and watch until the flames blur into red and orange and gold. My eyes sting and I shut them, just for a minute. The fire melts into velvety blackness. There are stars in the blackness and I want to count them one by one, but they’re dancing too fast…

I must have fallen asleep. Suddenly Dad’s here, swooping down out of the night to pick me up.

“All right, Sapphy? Hold on tight now and I’ll carry you down the hill.”

I’m too big to be carried, but it’s Midsummer Night and Dad says that’s the one night when all the rules can be broken. He picks me up, still wrapped in the rug with my feet poking out. I look back over his shoulder. The fire has flattened down into a heap of red ash. People are still sitting around it drinking, but the dancing’s over.

The path that leads down to our cottage is rough and steep, but Dad won’t let me drop. My dad is strong. He takes his boat out in most weathers and he can swim more than three miles. He has a medal for life-saving.

Mum and Conor are walking ahead of us on the path down. They’re talking, but I can’t hear the words. I put my arms round Dad’s neck and hold on tight, partly because the path is rough and partly because I love him. His strength makes me feel so safe.

Dad begins to sing. He sings O Peggy Gordon and his voice rises up loud and sweet into the summer night.

I wish I was away in Ingo

Far across the briny sea,

Sailing over deepest waters…

I love it when Dad sings. He has a great voice and people used to say that he should be in the church choir, but Dad only laughs at that.

“I’d rather sing in the open air,” he says. It’s true that when he’s working in our garden people lean against our wall to listen to him. Dad likes singing in the pub as well.

Mum, Dad, me and Conor. All of us going home safe on a summer night.

I always think that our family is made up of two halves. There is Conor and Mum, who are calm and sensible and always do what they say they’re going to do. And there’s me and Dad. We flare up like the Midsummer Bonfire, lose our tempers and say things we should never say. Sometimes we don’t know what we’re going to do until we’ve done it. And I sometimes tell lies when I need to, which Conor never does. Conor tells you the truth straight out. You just have to get used to it.

But it doesn’t matter that we’re a family of two halves, as long as we stick together.

We come to the steepest part of the path, and Dad has to put me down. Westward over the sea there is still a bit of light, like the ghost of a sunset or maybe the ghost of the moon rising. The sea stretches out dark in the distance. I’m glad that Dad’s stopped here, because I love to watch the sea.

Dad has stopped singing too. He stands there still and silent, staring way out to sea. He looks as if he’s searching for something. A boat maybe. But there won’t be any boats out tonight. Not on Midsummer Night.

Even though Dad’s standing next to me, I feel as if he’s forgotten me. He’s far away.

“Dad,” I say at last. I feel uneasy. “Dad?” But Dad doesn’t answer. I’m tired and cold now and my legs are shivery. I just want to be at home, all four of us safe inside our cottage, with the door shut. I want to be in bed, falling into sleep.

“Dad, let’s catch up with Mum and Conor. They’re way ahead of us. Da – ad—”

But Dad holds up his hand. “Hush,” he says. “Listen.”

I listen. I hear an owl hunting. I hear the deep noise of the sea, like breathing. On a calm night you have to listen for it, but it’s there all the time. You would only hear silence if the world ended and the sea stopped moving. As soon as this thought comes into my mind the uneasy feeling gets stronger. I don’t like this. I’m afraid.

“Listen,” says Dad again. The way he says it makes my skin prickle all over with fear.

“What, Dad?” I say sharply. “What are you listening to?”

“Can’t you hear it?”

“What?”

But Dad still won’t answer. He stares out to sea a little longer and then he shakes himself as if he needs to wake up.

“Time to go, Sapphy.”

It’s too dark for me to see Dad’s face clearly, but his voice is normal again. He swings me back up into his arms. “Let’s be getting you home.”

By the time we reach our cottage, Mum has already sent Conor upstairs to bed.

“Go on up now, Sapphy,” says Dad. He stretches and yawns, but his eyes are brilliant and wide awake. I notice that he’s left the door ajar, as if he’s planning to go back outside. The front door to our cottage comes straight into our living room, and then you go through the back to the kitchen. Mum’s in the kitchen, clattering plates.

“I’m away down to the shore,” Dad calls to her. “I can’t settle to sleep yet.”

Mum emerges from the kitchen, blinking with tiredness.

“What? At this time of night?”

“It’s a wonderful night,” says Dad. “The longest day and the shortest night. Think of it, Jennie, we won’t get another night like this for a whole year.”

“You’ll break your neck on the rocks one of these nights,” says Mum.

But we all know he won’t. Dad knows his way too well.

This is how you get down to our cove. The track runs by our cottage. You follow it to the end, and then there’s a path where bracken and brambles and foxgloves grow up so high that you wouldn’t find the way unless you knew it. Push them aside, and there’s the path. When I was little I used to pretend it was magic. You go down the path, and suddenly you come out on to a grassy shelf above the cove. You might think you’re nearly there, but you’re not, not at all. You have to scramble over the lip of the cliff and then climb down over a jumble of huge black rocks.

The rocks are slippery with weed. Sometimes you have to stretch yourself down for the next foothold. Sometimes you have to jump. Sometimes you fall. Conor and I have both got scars on our legs from falling on the rocks.

Down and down, and then you can squeeze between the two boulders that guard the way to the cove. It’s damp and dank in the shadow of the boulders, and it smells of fish and weed. Conor and I find long-legged spider crabs there, and lengths of rope, and fish skeletons, and pieces of driftwood.

After you pass through the boulders there are more rocks to climb across. But you can see the beach now. You’re nearly there.

The beach. Our beach, made of flat, white sand. The best beach in the world.

You jump down on to it. You’re there! But the beach only exists at mid to low tide. At high tide it disappears completely, and the whole cove is full of the sea.

But when the beach is there, you can swim, climb on the rocks and dive, picnic and sunbathe, make a fire of driftwood and cook on it, explore the rock pools, watch the gulls screaming round their nests… Conor and I go there nearly every day in summer, when the tide’s right.

Sometimes we explore the caves at the back of our beach. They’re all dark and slimy, and they echo when you call. Hello… lo… lo… Can you hear me… hear me… hear me…

The air’s clammy, and there’s a sound of water dripping. You can’t tell where it’s coming from. You can wriggle your way down narrow passages, but not too far in case you get stuck and the tide comes in and drowns you. Imagine being stuck in a slimy tunnel of rock while the cold sea curls round your toes and then your legs, and you know all the time what’s going to happen, no matter how much you struggle.

“Keep a sharp lookout when you’re in those caves,” Dad always tells us. “Don’t forget the time. The tide comes in fast, and you could get cut off.”

You have to watch the tide. When the water reaches a black rock that me and Conor call the Time Rock, it’s time to go. Back over the sand, scramble over the stones, squeeze between the boulders and then up the rocks, as fast as you can. No good thinking you can swim for safety. If you tried to swim around the headland you’d be caught by the rip and carried away.

Dad keeps his boat on the other side of the rocks, where it’s deep water. When the weather’s bad the waves could smash the boat against the rocks, so Dad has a winch to haul the Peggy Gordon up above the tide line. Dad’s always out in the Peggy Gordon, fishing or checking the crab pots, or else taking photographs. He takes photos and changes the images on his computer and he writes text on them; then they get framed and he sells them to tourists.

So when Dad says he is going down to the cove, there’s no reason to worry. Dad would never break his neck on those rocks, and it will be dawn before long. I used to be scared when he was out in his boat and the weather turned bad, but he always came home safe. He knows every wrinkle of the coast. I know every pool of saltwater and every creature in it, he says, and it doesn’t sound like boasting, because it’s the truth.

But tonight, Mum’s worried.

“Don’t go, Mathew,” she says. “It’s much too late. Let’s get to bed.”

“Why don’t you come with me?” he answers. I can tell he really wants her to come. “Why don’t you leave these children for once and come with me?”

He says ‘these children’ as if it’s strangers he’s talking about, not me and Conor. As if I’m not even in the room. I hate it. I feel cold again, and scared.

“How can I leave Sapphire in the middle of the night?” asks Mum.

“What’s going to happen? You’ll be all right, won’t you, Sapphy, if me and Mum take a walk together down to the cove? Conor’s only upstairs.”

I look at Mum, then back to Dad.

“Yes,” I say, in a voice that means no. Mum’s got to understand that I mean no…

“She’s too young,” says Mum. “It’s all right, Sapphy, don’t look so scared. I’m not leaving you.”

Dad flashes with anger. “Are we never going to have a life of our own again?” he asks fiercely. “They’re not babies any more. Come down to the sea with me, Jennie.”

But Mum shakes her head. I feel guilty now as well as scared. I hate it when Dad’s angry, and it’s my fault this time.

“I’ll go on my own then,” says Dad. His face is hard. He turns away. “Don’t bother to wait up for me, Jennie.”

“Mathew!” says Mum, but the door swings wide and Dad’s vanished into the night. The door bangs.

“Go on up to bed now, Sapphy,” says Mum, in a tired, quiet voice.

I go up to bed. There are two bedrooms in our cottage. Mum and Dad sleep in one, and I sleep in the other. Conor has the best deal of all. There’s a ladder up from my bedroom that goes into the loft, where Conor sleeps. Dad made him a window in one end. When Conor wants to be alone he can pull up the ladder and no one can get him.

I get undressed, thinking sleepily about the bonfire, and about Mum and Dad arguing, then I put it all out of my mind. I roll into bed and snuggle down deep under the duvet and sleep comes up over me like a tide.

I don’t know anything yet.

I don’t know that this is the last night of me and Conor, Mum and Dad, all safe together. I don’t know that the two halves of my family are starting to rip apart while I sleep.

But I dream about the mermaid of Zennor. I dream that I’m tracing the deep knife cut that slashes across her body. I’m trying to rub it out, so that the mermaid will be whole and well again. I dream that she opens her wooden eyes and smiles at me.

CHAPTER TWO (#ulink_5a3561bf-f903-54ea-a1c1-06faae8109b0)

Next morning I wake up late to the smell of cooking. Dad’s in the kitchen, frying mushrooms in the big black pan. He’s whistling softly through his teeth. Mum’s banging knives into the drawer.

“He didn’t come home until eight this morning,” Conor whispers to me.

The atmosphere in the kitchen is thick with anger. Conor and I retreat into the living room with a bowl of cereal each. As we eat, they start to quarrel again. Their voices grow loud. “Are you crazy, Mathew, taking that boat out at night alone when you’d been drinking?”

“I didn’t take the boat out.”

“Don’t lie to me. I can smell the sea on you. Look at the wet on your clothes. It wasn’t enough to risk your neck climbing down those rocks in the dark, you had to take the boat out too. I haven’t slept a wink. Are you out of your mind?”

Dad’s voice crashes back. “I know what I’m doing. I’m in no danger. Are you going to stay on land for the rest of your life, Jennie? If you’d only come with me—”

His voice breaks off. He’s angry with Mum, too, just as much as she’s angry with him. But why? Dad knows Mum hates the sea. She never goes out in the boat, and for once I’m glad of it. It makes me shiver to think of them both away out there on the sea, on the dark water. So far away that even if I called as loud as I could, they’d never hear me.

“You know why I won’t come,” says Mum. “I’ve got good reason to keep away from the sea.” Her voice is full of meaning. We’re so used to the idea that Mum hates the sea and won’t go near it that we don’t ask why, but suddenly I want to know more.

“Conor, why won’t Mum ever go out in the Peggy Gordon?” I whisper. It’s always, always been Dad who takes me and Conor out on the sea, and Mum who stays at home. Conor shrugs, but suddenly I see in his face that he knows something I don’t.

“Conor! You’ve got to tell me. Just because I’m the youngest, no one ever tells me anything.”

“They didn’t exactly tell me, either.”

“But you do know something.”

“I heard them talking one day,” says Conor reluctantly. “Mum was saying that she was going to cook a saddle of hare for Sunday dinner.”

“Hare! Yuck! I’m not eating that.”

“Yeah, that’s exactly what Dad said. He said it was bad luck to eat a hare. So Mum said she didn’t care, she wasn’t superstitious. Dad said she was the most superstitious person he’d ever met in his life. And Mum said, Only over one thing, Mathew. And I’ve got a good reason to fear the sea.”

“What did she mean? What good reason?”

“I asked Dad later. I said they were talking so loud I couldn’t help overhearing. He wasn’t going to tell me, and then he did. He said a fortune-teller had told Mum’s fortune once, and after that she’d never gone out on the sea again. It was years ago, but she never has. Not once.”

“What do you think the fortune-teller said?”

“Dad wouldn’t tell me. It must have been something really bad, though.”

“Maybe the fortune-teller said that Mum would die by drowning.”

“Don’t be stupid, Saph. A fortune-teller wouldn’t ever say that to someone. You’re going to drown, that’ll be ten pounds please.”

“But she must have told Mum something terrible. Mum wouldn’t stop going in boats for the rest of her life otherwise—”

“Saph, please don’t go on about it or I’ll wish I hadn’t told you. And don’t let them know you know. Dad said not to tell you in case you got scared.”

Mum and Dad’s voices rise again. Why do they have to argue so much? I hardly ever quarrel with Conor.

“I’m going in to make some toast,” says Conor. “That’ll stop them.”

“I’ll come with you.”

Mum and Dad are standing by the stove. They go quiet when they see us, but the air prickles with all the bad things they’ve said. Sometimes I think that if adult quarrels had a smell, they would smell like burned food. Dad’s mushrooms are shrivelled up and black. He sees me looking at them, and he picks up the pan and scrapes the burned mushrooms into the pig bin.

What a waste. I love mushrooms.

The next night Conor and I bike up to see his friend Jack. We stay longer than we mean to, because Jack’s Labrador bitch has three puppies. We haven’t played with them before, because they’ve been too little, but now they’re seven weeks old. Jack lets us hold one each. My puppy is plump and wriggly and she sniffs my fingers, licks them, and makes a hopeful whining sound in the back of her throat. She is so beautiful. Conor and I have always wanted a dog, but we haven’t managed it yet.

“You are the most beautiful puppy in the whole world,” I whisper to her, holding her close to my face. She has a funny little folded-down left ear, and soft, inquisitive brown eyes. If I could choose one of the puppies, it would be her. She wrinkles her nose, does a tiny puppy sneeze, and then snuggles in under my chin. I feel as if she’s chosen me already.

Poppy, the pups’ mother, she knows us, so she doesn’t mind us playing with them. She stays near, though, looking pleased and proud and watchful. Every time a pup tries to sneak away to explore, Poppy fetches it back and drops it in the basket. I love the way Poppy makes her mouth soft to pick up the pups by the scruff of their neck.

We forget all about the time. When we remember, it’s getting late and we have to rush.

“Come on, Saph. Mum’s going to kill me if we’re any later!”

Conor’s up ahead, racing. My bike’s too small for me and I have to pedal like crazy, but it still won’t go fast. When Conor gets a new one, I’ll have his old one. Dad says maybe at Christmas Conor will get his new bike.

“Wait for me!” I yell, but Conor’s away in the distance. At the last bend he waits for me to catch up.

“You are so slow,” he grumbles, as we bike the final downhill stretch side by side.

“I’m just as fast as you are, it’s only my bike that’s slow,” I say. “If I had your bike…” Conor’s already told me he’ll paint his old bike for me when he gets a new one, and I can keep the lights. He’ll paint it any colour I like.

We reach the gate where the track goes down past our cottage. Ours isn’t the only cottage here, but our neighbours are set far apart. At night we can see the lights from the other cottages’ windows, shining out against the dark hillside. Our cottage is closest to the sea.

“Look, there’s Mum. What’s she doing?” asks Conor suddenly.

Mum has climbed to the top of the stile opposite our cottage. She’s standing there, outlined against the light of the sunset. She strains forward, as if she’s looking for something.

“Something’s wrong,” says Conor. He drops his bike on the side of the track and starts to run. I drop mine too, but its handlebars get tangled up with Conor’s bike. I stop to sort out the bikes and prop them against the wall. I want to run to Mum, but I also don’t want to. I hang back. I have a cold feeling in my heart that tells me that Conor is right. Something is wrong. Something has happened.

This is when the long night begins. The longest night of my life so far, even though it’s summer and the nights are short.

None of us goes to bed. At first we all sit together in the kitchen, round the table, waiting. Sometimes I start to fall asleep. My head lolls and then I lurch out of sleep just before I tip off my chair. Mum doesn’t notice, and she doesn’t send me to bed. She watches the door as if any moment it will open, and Dad will be back.

“Dad often takes the boat out this late,” Conor keeps saying stubbornly, as the clock moves on. Ten o’clock. Eleven o’clock.

“Not like this,” says Mum. Her lips barely move. I know that she’s right, and so does Conor. Something’s wrong. When Dad goes fishing he usually goes with Badge or Pete. He does go on his own sometimes, but he never, ever just disappears without telling us where he’s going. We help him load up the boat and often we watch him go out on the tide.

But this time Dad has said nothing. He was working in the garden all afternoon. Mum heard him singing. She went to lie down for half an hour, because she was so tired from not sleeping the night before. She must have fallen asleep. When she woke the sun was low. She called to Dad, but no one answered. She went down the track and called again but everything was still. Our neighbour, Mary Thomas, came out.

“Is something wrong, Jennie?” she asked. “I heard you calling for Mathew.”

“No, nothing’s wrong,” said Mum. “It’s just I don’t know where he is. Maybe he’s working on the boat. I’ll go down to the mooring and check.”

Imagine Mum going all the way down to the cove, so near to the sea. She must have been scared, but she did it. She slipped on a rock as she climbed down, and cut her hand on mussel shells and got blood all over her jeans. She went down as far as she dared, until she could see that there was no boat tied up at the mooring place. The tide was high, just on the turn. Mum called and called again even though she was sure by now that Dad wasn’t there. She couldn’t stop herself calling.

“I had a feeling that Mathew was nearby. He was trying to get to me, but he couldn’t.”

Mum doesn’t tell us all this as we sit around the kitchen table. Much later that night, when she’s told us to go upstairs and get some sleep, we sit on the stairs and listen to her talking to Mary Thomas, telling her all the things she hasn’t told us – about calling Dad, and thinking he was nearby, but he couldn’t get to her.

Dawn comes, and Dad’s still not back. Mary Thomas is with Mum in the kitchen. Conor and I are still sitting on the stairs, waiting and listening. I must have fallen asleep, because suddenly I wake up with Conor’s arm round me. I’m stiff all over. My head hurts and the heavy frightened feeling inside is stronger than ever.

Mum said Dad would be back in the morning. But it’s morning now, and he’s not here. There’s a murmur of voices through the closed kitchen door, and we strain to make out what Mum’s saying.

“I don’t know what to do now, Mary!” she says, and we can hear the fear and panic in her voice. I wait for Mary to tell her to relax and calm down, because Dad’s been out in that boat a million times and no harm has ever come to him. But Mary doesn’t. Morning light creeps into our cottage, and Mary says, “Maybe we should call the coastguard now, Jennie.”

“Come on Saph,” says Conor. He stands up, and his face suddenly looks much older. We push through the kitchen doorway, and Mum stares at us as if she’s forgotten who we are. She looks awful.

Mary says to Conor, “I was saying to your mum, Conor, that maybe it’s time to call the coastguard now. It’s not like your father to go off like this and leave your mother worrying. There’s enough light to search by. If he’s out there fishing, there’s no harm done if the coastguard happens by. I’ll get the phone for you now, Jennie.”

Mum phones, and everything begins. Once it starts you can’t stop it. I’m still clinging to the hope that the police and the coastguard will say we’re being stupid to bother them. Take it easy, your dad’ll be fine. Wait a while and he’ll turn up. But they don’t.

The coastguard Jeep comes bouncing down the track. People talk into radios and mobiles. The police crowd into the kitchen, filling it with their uniforms.

Neighbours knock on the door. Mary goes out to talk to them, quietly, so that none of us will hear her telling the story over and over again. There are mugs of tea on the kitchen table, some empty, some half full. People start bringing sandwiches and cakes and biscuits until there’s so much food I think it’ll never get eaten I can’t eat anything. I try to swallow a biscuit and I choke, and Mum holds a glass of water to my mouth while I sip and splutter. Mum’s face is creased with fear and lack of sleep.

The old life of me and Dad and Mum and Conor has stopped like a clock. Another life has begun. I can hear it ticking: your dad has gone, your dad has gone, your dad has gone.

The sun shines brightly, and it’s getting warm. Conor stays downstairs with Mum but I go up to my bedroom and wrap the duvet tight around me and shut my eyes and try to bring Dad back. I shut out all the sounds of people in the kitchen below, and concentrate. If you love someone so much, how can he not hear you when you call to him?

“Dad,” I say, “Dad. Please. Please come home. Can you hear me, Dad? It’s me, Sapphy. I won’t let Mum be angry with you if you just come home.”

Nobody. Nothing. All I can hear is the rushing sound of my own blood, because the duvet is wrapped around my ears.

“Dad, please…”

I sit up, cold all over, and strain my ears for the two things I want to hear more than anything else in the world. One is the beating of Dad’s heart, as I heard it when he was carrying me down from the Midsummer Fire. The other is his voice rising up in the summer air, singing O Peggy Gordon.

O Peggy Gordon, you are my darling,

Come sit you down upon my knee…

My name’s not Peggy, I used to say when I was little. Come and sit on my knee anyway, Dad always answered, and he’d cup his hands under my elbows and swoop me up to sit on his lap and I would bounce and laugh and he would laugh back and bounce me higher and higher until Mum told him to stop before I was sick. But she wasn’t ever angry then. She was laughing too.

If only time would go back, like the tide. Back and back, past yesterday, past the night before. Back when the bonfire wasn’t lit, back to when none of this had happened. And then we could all start again…

The coastguard search up and down the coast, but they find nothing. All that day they search, all the next day and the one after. A helicopter comes down from the air-sea rescue. It flies low and hammers the air, searching coves and cliffs.

After two days Conor explains to me that they are now scaling down the search. He tells me what that means. It means that if Dad is in the sea, or on the cliffs, they don’t believe that they’ll find him safe any more. Too much time has passed. The helicopter stops flying, and there are only neighbours in our kitchen now, instead of police and coastguards and volunteer searchers. And then the neighbours go back to their own lives, except for Mary.

A few days later Mum says she thinks it’s better if we both go back to school. It isn’t doing us any good, staying in the cottage and waiting, always waiting.

Five weeks later a climber on the cliffs miles down the coast sees something. It’s the hull of the Peggy Gordon, wedged upside down between the rocks. He reads the name on it. The coastguards go down, and a team of divers searches the area. There is no sign of Dad. Finally, they pull the boat off the rocks and tow it into shore, so they can examine it thoroughly and find out what caused the accident. But the boat doesn’t give a single clue.

Mum says to us, “We have to accept it now. Your Dad had an accident.”

“No!” says Conor, slamming his fists on the table. “No, no, no. Dad wouldn’t lose the Peggy Gordon like that, on a calm night. That’s not what happened.” He bangs out of the house and gets his bike and disappears. I think he goes up to Jack’s. Anyway he comes home late, and when he creeps into my room to climb up his loft ladder, I’m already half asleep.

“Conor?”

“Ssh.”

“It’s all right. Mum’s asleep. She’s been—”

“Crying?”

“No. Just sitting, not looking at anything. I hate it when she does that.”

“I know.”

“Conor, where’s Dad?”

I’m still half asleep, or I’d never ask that question. How can Conor know, when nobody knows? The question just slips out. But Conor doesn’t get angry. He tiptoes over and kneels by my bed.

“I don’t know what happened, Saph. But he’s not drowned. I’m sure of it. We’d know if he was drowned. We’d feel it. We’d feel a difference, if he was dead.”

“Yes,” I say. Relief floods me. “You’re right. I don’t feel as if he’s dead either.”

Conor nods. “We’re going to find Dad, Saph. However long it takes. But you mustn’t tell Mum. Swear and promise.”

“Swear and promise,” I answer, and I spit on my right palm and Conor spits on his, and we slap our palms together. After that I sleep.

They hold a memorial service for Dad in the church. Mum explains that we can’t have a proper funeral, because Dad’s body hasn’t been found. It hasn’t been found because there isn’t a body to find. Dad isn’t dead, I think to myself, and I know Conor is thinking the same thing.

Everyone comes to the memorial service in dark clothes, with sad faces.

“Oh Jennie, Jennie dear,” they say, and they put their arms round Mum. Some women kiss me, even though I don’t want them to. Conor stands there frowning, with his arms folded so no one will dare to kiss him. Conor’s angry because everybody’s flocking to the memorial service like sheep, believing that Dad’s dead, even though no one has found his body. Most people think that Conor is being brave, for Mum’s sake.

“You’re the man of the house now, Conor,” says Alice Trewhidden in her creaky old voice. “Your mother’s lucky that she’s got a son to take care of her.” Alice only likes boys, not girls. In fact girls practically don’t exist in Alice’s eyes.

“Conor has his own life to live, Alice,” says Granny Carne sharply. I didn’t see Granny Carne arrive, but suddenly she’s there, tall and strong and wild-looking. People fall back a little, to give her room, out of respect. Everyone shows respect to Granny Carne, as if she’s a queen. “Conor has his own choices to make,” Granny Carne goes on. “None of us can make them for him.”

Grumpy, sharp-tongued Alice Trewhidden says nothing back. She just mumbles under her breath and shuffles off sideways like a crab to find the best seat. She’s not exactly scared of Granny Carne, but she doesn’t want to cross her. Nobody does.

I’m surprised that Granny Carne has come to the memorial service. I’ve never seen her inside the church before. Everybody else looks surprised too. Heads bob round to look at her as she comes in, and murmurs fly around the cool, echoing space.

Look who’s here!

Who?

Granny Carne. Can’t remember the last time we saw her inside the church.

“I never seen her inside this church in my life, and that’s going back many years,” mutters Alice Trewhidden.

Granny Carne doesn’t go far inside the church today. She stands by the open door at the back, watching and listening. Maybe she hears all the mutters and murmurs, but she takes no notice. She wears her usual shabby old earth-coloured clothes, but her poppy-red scarf is the brightest thing in the church.

Granny Carne is tall and forbidding. People are still pushing their way into the crowded church, and they glance sideways at her as they come in, and a lot of them nod respectfully, just the same way as they nod to the vicar. The thought of Granny Carne being like the vicar makes my lips twitch.

Granny Carne catches me looking at her. The faintest smile crosses her face. Suddenly I feel a flicker of hope and courage in the dark sadness of the church.

Who is Granny Carne? Why is she different from everyone else?

I remember asking Dad that, when I was about seven. We were sitting on the beach on a day of flat calm, and Dad was skimming stones on the water with a flick of his wrist. Just Dad and me, on our own. The stones hopped on the silky smooth water. One jump, two, four, six jumps—

“Dad, who is Granny Carne? Why do they call her that when she’s not anyone’s real granny?”

“Some say she’s a witch,” answered Dad.

“I know,” I said. I’d heard that in the playground. “But there aren’t real witches now, are there?”

“Who knows?” said Dad. “She has power in her, that’s for sure. If you want to put a label on it, you could call it witchcraft. Or you could call it magic.”

“Does she do spells, Dad?”

“Out of a great big spell book, do you mean?”

“Or she might know them off by heart.”

“She might. She has earth magic in her. That’s why she’s so strong, old as she is.”

“How old is she, Dad?”

Dad shrugged. “She’s always been as old as she is now. If you ask her how old she is she’ll say she’s as old as her tongue and a little bit older than her teeth. Maybe she’s been old for ever.”

“Are you scared of her, Dad?”

“No, I’m not scared. There are two sorts of magic, Sapphy. I’d say that Granny Carne’s magic is mostly benign.”

“What does that mean?”

“That her magic does good, rather than harm. Most of the time.”

“Not all the time?”

“Magic’s wild. You can’t put a harness on it, or make it do what you want. Even the best magic can be dangerous.”

I remember being very surprised that Dad talked about magic as if it was a real thing. I knew that most grown-ups didn’t believe it was.

“Always show respect to Granny Carne, Sapphy,” said Dad. “If you do that, and you don’t cross her, she’ll be a good friend to you. She’s always been a good friend to me. Never whisper about her behind her back, like ignorant people do. You think she doesn’t know, but she does.”

Benign. Dad thought that Granny Carne’s magic was benign. I didn’t even know what the word meant then, but much later I looked it up in a dictionary. Characterised by goodness, kindness, it said. I thought about good magic, and wondered what Granny Carne’s magic was really like.

And here she is at Dad’s memorial service, dressed in earth colours and red like flame, not in best black like all the others crowding into the church. Her face is deep brown from wind and sun, and her eyes are yellow amber, like an owl’s.

Is there such a thing as owl magic? Maybe Granny Carne is really an owl, changed to a human and sailing high above the church and then swooping down on us. Owls are strong and powerful and wise, but they can tear you with their claws. Mostly benign, Dad said. Her owl-eyes are piercing and full of light, as if they can see everything you try to hide.

People have come to the church from miles around, in their dark clothes. Mum and Conor and I sit in the front pew. No one except the vicar can see our faces.

The choir sings, but no one has a voice as good as Dad’s. I remember what Dad said about wanting to sing in the open air, instead of inside the church, in the choir. If Dad was here, he wouldn’t stay. He’d slip out of the open back door. He’d wink at Granny Carne as he went. I nearly laugh when I think of Dad escaping from his own memorial service, but I stop myself.

Oh hear us when we cry to thee

For those in peril on the sea…

They sing this hymn because it’s the hymn for sailors and fishermen, and they believe that Dad has drowned.

And ever let us cry to thee

For those in peril on the sea…

Mum doesn’t sing. She stares straight ahead as the song swells louder. Her lips are pressed so tightly together that there’s no colour in them. If you didn’t know Mum was sad, you’d think she was furiously angry. She often looks like that since Dad went. It’s such a slow, gloomy, droning hymn. Dad would hate it. He likes music to have life in it.

I close my eyes, and shut my ears to the church hymn. I strain to listen to a different music. Yes, I can almost believe that I hear Dad’s voice:

I wish I was away in Ingo

Far across the briny sea,

Sailing over deepest waters…

Maybe that’s where Dad has gone, sailing over deepest waters. He’s away in Ingo, wherever Ingo is. That’s where we’ll find him. If I can just catch one note of his voice, I’ll be able to follow it. I’ll follow a single thread of his voice, to where Dad is.

The hymn ends. People cough and rustle as they sit down, cramming themselves into the tight pews. Fat Bridget Demelza is spilling over the edge of the pew and into the aisle. I turn to Conor and whisper, “We’ll find him, won’t we, Conor?”

“Yes,” whispers back Conor. “Don’t worry, Saph. Let them get on with their memorial service if it makes them happy. It doesn’t mean Dad’s dead. I know we’ll find him.”

We’ll find Dad in Ingo, I tell myself. In Ingo, however long it takes. We’ll find Dad, however hard it is.

No, I am not going to cry. I tip my head back so the tears that are swelling in my eyes will not fall. They run down the back of my throat and into my mouth, tasting of salt. I swallow them. Dad’s still alive. He wouldn’t want me to cry.

CHAPTER THREE (#ulink_d9c6cf0e-2f76-5415-9197-ee6f42a58b36)

It seems like a hundred years since the day of Dad’s disappearance. But really it’s a year and a month and a day. Three hundred and ninety-six days.

Sometimes when I first wake up I don’t remember. I think I can hear Dad downstairs, or in the bathroom. Everything’s normal. And then it sweeps over me like a dark cloud.

In the daytime I make myself forget. It doesn’t always work, even when I’m doing things I love, like swimming or eating chocolate cake, or designing stuff on the school computers. The thought of Dad is always in my mind somewhere, like a bruise. It’s the same for Conor. We don’t talk about Dad in front of Mum, because she gets upset. We hate her getting upset. She’s a lot better than she was. She eats proper meals now, and she doesn’t get up in the night and drink cups of tea and walk about downstairs for hours.

We never, ever tell Mum that we think one day we’ll find Dad again. She wouldn’t believe us anyway.

I used to run to the phone every time it rang.

Yes? Hello? Who is it?

Each time it wasn’t Dad’s voice I felt as if all the lights had been switched off. When the postman came I’d try to get to the door first, and grab the letters with my heart pounding. But it was never Dad’s handwriting on the envelopes. Even when somebody knocked at the door my hopes would spring up again. But why would Dad knock at the door of his own house?

I don’t do those things any more. The phone ringing is just the phone ringing, the postman’s probably bringing another bill, and a knock on the door means a neighbour.

You know how the sea grinds down stones into sand, over years and years and years? Nobody ever sees it, it happens so slowly. And then at last the sand is so fine you can sift it in your fingers. Losing Dad is like being worn away by a force that’s so powerful nothing could resist it. We are like stones, being changed into something completely different.

If you looked casually at me and Mum and Conor now, you might think we were the same people as we were a year ago, except that we’re a year older. But we are not the same people. We’ve changed where no one can see it, inside our minds and our feelings. I didn’t want us to change, but I can’t stop it.

“Where’s Conor? Have you seen him?” Mum’s rushing round, getting ready for work. She’s always rushing these days, but at least that means that she never just sits, staring into space…

Mum’s on the evening shift this week, at the restaurant where she works in St Pirans. She leaves at four, and she’ll be back after midnight.

Mum stops in front of the living-room mirror to pin up her hair and put on her lipstick. She never used to wear lipstick every day…

“Sapphire! Are you listening to me?” Mum snaps. I jump. Mum snaps quite a lot these days. She doesn’t mean it, it’s because she’s always tired. She works in one of the expensive new restaurants down by the harbour. The tips are good, but the hours are long in the summer season. Mum got a twenty pound note from one party last week. Twenty pounds! Imagine having so much money you can give away a twenty pound tip on top of paying for your meal. But then there are also mean people, who spend a hundred pounds on one dinner, and think a pound tip is enough—

“Sapphire! Will you please stop daydreaming!”

“Sorry, Mum.”

“For the third time, where’s Conor?”

“Gone up to Jack’s.” I have no idea where Conor is, but I want Mum to go off to work happy.

“I told him to be back by three,” says Mum. “I don’t like leaving you here on your own, Sapphy. Yes, I know you’ll be all right, but I feel safer if Conor’s here. Oh dear, these school holidays, they go on for ever.”

“But they’ve only just started, Mum!”

“It’s all right for the teachers. They get the whole holiday off work, to be with their own kids. They don’t have to go to work all summer and worry themselves half to death about leaving their children on their own—”

“Mum, we’re not little kids. We’re really sensible, and anyway, Conor’ll be back in a minute. But Mum, I wouldn’t ever be on my own if we had a dog—”

“Sapphire, please don’t start that dog business again. Oh no, now I’ve messed up my lipstick.”

“I think you look nicer without lipstick.”

“The customers don’t,” mumbles Mum as she wipes off the smudged lipstick and puts on more.” Look at the rings under my eyes, Sapphy, I need a bit of colour… Now, if Conor’s not back by five, call me on my mobile.”

It is so unfair. Jack’s got three dogs and we haven’t even got one. His mum said we could have Sadie, my favourite puppy, the one with the folding-down ear, but Mum wouldn’t let us. We kept telling Mum we’d look after Sadie and take her for walks and do everything, but Mum said what would happen when she was at work and we were at school?

Sadie is so beautiful. She’s over a year old now, but Jack’s family hasn’t sold her to anyone else. Her coat is pale biscuity gold and she has huge soft brown eyes that look at you as if she knows all about you. And she understands when you tell her things. I take Sadie out for walks whenever I can. It’s a little bit like having a dog of my own, when I’m out with her. She comes to heel immediately when I say, “Heel, Sadie!” People who go past in cars probably do think she’s my dog.

Sadie is so affectionate, but she’s not clingy. In fact she has a perfect character. She always gets so excited when she sees me. Dogs can tell if you really love them. If Jack’s mum and dad ever sold Sadie to someone else, I don’t think she’d be happy. I know she’d miss me as much as I’d miss her—

“Sapphire, listen,” says Mum. “There’s a pepperoni pizza in the freezer, and Mary’s lettuce, and those spring onions.”

I nod. I hate spring onions. Why does anyone bother to grow them?

“You’ll be all right, won’t you?” says Mum, frowning anxiously. She hates leaving me alone, and she’ll worry about it while she’s at work. She’s got to work, because we need the money. Dad didn’t have any life insurance.

I hate Mum worrying.

“Mum, we’ll be fine.”

Mum gives me a quick rushing-out-of-the-door kiss, and she’s gone. I listen to the car starting then Mum toots the horn and I remember I’ve got to open the gate at the end of the track for her. I run outside, untie the orange twine from the gate post and swing the gate wide. Mum accelerates through, waving at me with a bright smile that doesn’t fool me for a second.

Back into the cottage. It’s too warm inside, and so I leave the door open. I wonder where Conor is?

He’ll be up at Jack’s, on Jack’s computer, or playing with the dogs.

But Conor usually tells me where he’s going. He doesn’t just disappear.

No. Don’t think about that word. I’ll make our tea. We’ll have it early and then we can watch loads of TV. I get out the pizza and put it on a baking sheet. I wash Mary’s lettuce, shake it dry, and carefully cut the roots off the spring onions for Conor. We haven’t grown any vegetables ourselves this year. Dad did all the gardening, and usually he grew everything: onions and potatoes and beans and peas and carrots and all our salad stuff. I used to help him. But now our garden is tangled and overgrown and weedy, and I don’t know where to start clearing it. Dad would hate the way it looks.

But then I remember something. Deep in the weeds there are three gooseberry bushes. I wonder if any of the gooseberries are ripe yet?

They are. They are fat and juicy and when I hold them up to the light I can see the dark seeds inside the yellow skin. I run into the kitchen, get the colander, and start picking. We’ll have gooseberries with sugar and cream. There’s half a carton of clotted cream in the fridge, which Mum brought back from work yesterday.

I pick and pick. Brambles scratch my legs and gooseberry thorns jab at my hands, but I don’t mind. I’ve got nearly a whole colander full now. There’ll be plenty for tomorrow as well, so Mum will be pleased. Conor’s going to love them—

Conor. Where is he? Worry stabs through me again. I look at my watch and it’s twenty-five past five. Mum said to call her if he wasn’t back by five, but I can’t do that. She’d be so scared. She might have an accident from driving back here too fast. And she’d lose a whole night’s pay.

I look around. Everything’s still. Way in the distance I can see Alice Trewhidden watering the geraniums by her front door. Even from a distance you can see the crabbed way that Alice moves. She has to peer up close at things before she can see them. No good asking her if she’s seen Conor.

I could ask Mary.

No, I won’t. Conor hasn’t disappeared. He’s late back, that’s all. If I ask Mary, it will make Conor’s absence seem serious, like the night when Dad—

No. Don’t think about it. I never, ever want to visit that awful night again.

I could phone Jack’s house. Maybe a bit later. But what if his mum answers and says, No, Conor’s not been up here today. Is everything all right, Sapphire?

I go back inside and put the colander of gooseberries on the kitchen table. I’ll top and tail them later.

The cottage seems quieter than ever. I can’t settle anywhere. I turn the TV on and then quickly turn it off, in case it stops me hearing Conor’s bike. Suddenly I think that maybe Conor is up in his bedroom, asleep.

“Conor?” I call. “Conor?”

Maybe he can’t hear me because he’s got the duvet over his head. I run up to my room and climb the loft ladder to Conor’s room, almost sure by now that he’ll be curled up under the duvet.

The bed is empty. The duvet is on the floor. I wonder if he’s left me a note on his pillow, the way people do in books, but of course he hasn’t. I end up searching all round the loft, as if Conor might have left a clue somewhere. I even bend down to peer out of the little window that Dad made. I remember him making it, after he’d boarded the loft for Conor. He let me sit on the floor and watch and pass his tools to him—

No. Sapphire, you are not allowed to think about things like that. They only make you—

They only make your eyes hurt. And Dad’s not dead. You know that. He’s just—

Stop making that stupid baby noise this minute.

Conor’s window. It looks straight out to sea. The sea is striped blue and purple and aquamarine in the late afternoon light. It’s very calm, although the swell is rolling in under the surface of the water. There’s a fishing boat near the horizon.

It’s much too hot and stuffy in Conor’s loft. If only I was down at the cove, walking into the water, feeling the delicious coldness of it move up my body. I’d walk in as deep as I could and the buoyancy of the water would lift me off my feet, and I’d be swimming. I would swim right out into the middle of the bay and lie on my back and stare up into the clear sky… Or maybe I’d dive down, deep, deep into the water, and open my eyes and see the ridges of sand that the tide makes on the sea floor, and the tiny shells. I’d see the red and orange weed that clings on to the rocks and sways to and fro as the tide comes in. I could watch the crabs scuttling when they felt my shadow over them, and the fish in little shoals, spurting this way and that. I could cup my hands into a little cave for the fish to swim in and out…

I’m falling into a dream, even though I’m wide awake. The sea feels stronger and more real than Conor’s loft room. The white walls seem to sway like water. The sea’s all around me, whispering to me in a voice that ebbs and flows like the tide. I want to follow its voice. I want to wade out into the water, far from everything on land. The sea is pulling at me, like a strong current that wraps itself around your legs and lifts you off your feet.

If only I was down at the cove. I must get there. I must go now, this minute.

CHAPTER FOUR (#ulink_22568971-9f0f-530d-b96f-a33759d3be6d)

I’ve never climbed down the rocks so fast, even though they’re wet and slippy. The sea’s only just been here, but now the tide’s turned and it’s falling, dragging me with it.

I jump down on to the sand. Another minute and I’ll be in the sea. I kick off my sandals. My toes are in the water, then my ankles, my knees…

The sea is dazzling. I lift my hand to shade my eyes, and as I do, I see him. It’s Conor, far away, sitting on the rocks at the mouth of the cove. I recognise him at once, even though he’s turned away from me. His hair is slick with water. He’s been swimming! But we never swim here alone, because we know how dangerous it can be. Why did Conor come without me?

Cold. I’m cold. I look down. Already the water is up to my waist. My hands trail in the water. That’s so strange. I didn’t think I had waded so deep. And I’m still wearing my shorts and T-shirt. The tide is falling fast and it’s pulling more and more strongly, as if it wants me to come with it. It’s like a magnet. If I didn’t dig my feet into the sand, the tide would carry me away with it.

But what’s Conor doing, sitting on the rocks at the mouth of the cove, where the water’s deep? He must have swum out there.

He hasn’t seen me yet. He’s still got his back to me. I open my mouth to call him. But suddenly Conor turns his head as if he’s…

…As if he’s talking to someone.

I push hard against the tug of the water. I’m not going to let it pull me in deeper. I’m not going to call to Conor. I turn round and the tide sucks my legs hungrily as I force my way back into shallow water. The sea doesn’t want to let me go, but it has to. Its power is broken.

Knee-deep in the water, I wade towards the left side of the cove. I’ll be able to see Conor better from there. I don’t want to attract his attention now. In fact I’m hoping that he won’t see me. From over here, I should be able to get a good view of the rock.

And now I can see them clearly. No, Conor’s not alone. There’s a second head outlined against the edge of the rock. A sleek, dark head. It turns, so I see the profile and the long wet hair. It’s a girl. Her hair is long, right down her back, like mine. And now I realise that what I thought was part of the rock is part of the girl’s body. She must be wearing a wetsuit. She and Conor are close together, talking like old friends who’ve got so much to say that they don’t notice anything or anyone else.

They haven’t seen me. Conor hasn’t even looked up. What are they talking about? They’re much too far away for me to hear their voices.

I’ve never seen her before, I’m sure of it. But I know everyone who lives round here. Who can she be?

Maybe she’s a tourist. Not many tourists come down to the cove, because it’s so hard to find. Maybe this girl asked Conor to help her find the way down, and then they got talking, and went swimming together… without me.

No, I don’t want them to see me. Conor will think I’ve been following him and spying on him. He didn’t want me here, or he’d have told me he was going down to the cove. We always swim together, not just because it’s dangerous to swim alone, but because we like being together.

I wade right out of the water. It pulls at my heels, but feebly now, as if it knows it’s not going to win. My wet shorts and T-shirt stick clammily to my skin. Maybe I should go back to the cottage and change? No, I don’t want to leave Conor, right out there. It isn’t safe.

I wander up and down the tide line, feeling cold even though the air is still warm. I pick up shells and tiny white pieces of driftwood, and let them drop again, and every few minutes I glance out to the rocks at the mouth of the cove. They are still there, Conor and the strange girl who doesn’t live round here, still sitting close together. And they haven’t noticed me at all. They only notice each other.

And then suddenly, the next time I look, the girl has vanished, and Conor is alone. He’s standing right on the edge of the rock, staring down into the deep water. But where has the girl gone? He looks down at the water and his body flexes, as if he’s about to dive in. A wave of panic sweeps over me, from nowhere. Before I know what I’m going to do, I’ve yelled out his name.

“Conor! CONOR!”

He looks up, stares around. I run along the water’s edge, waving and calling.

“Conor, it’s me! Conor!”

He turns and sees me. For a long moment we stare at each other across the water. We are too far away to see each other’s expressions. And then, slowly, he raises his hand and waves to me.

“Conor, come back! Tea’s ready!”

He waves again, and begins to pick his way carefully back across the wet, slippery rocks at the side of the cove. It would be quicker to dive in and swim across to me, but he doesn’t do that. He scrambles all the way back across the rocks that line the edge of the cove, and only jumps into the water when it is shallow. Knee-deep, he splashes towards me. He’s frowning – not in an angry way, but just as he frowns when he’s doing his toughest maths homework.

“What are you doing here, Saph?”

“Looking for you.”

“But it’s not time for tea yet, is it?”

I look down at my wrist, and then I realise something terrible. I must have walked into the water with my watch on. My beautiful watch that Dad got for me in Truro. Now I remember my arms trailing in the water. I forgot all about my watch! I can’t believe it. The hands point to five past seven, but the second hand isn’t moving. I shake my wrist hard. Nothing happens. My watch has stopped.

“Oh, Saph. You went into the water with it on,” says Conor, looking at my wet shorts and T-shirt.

“It’s broken.”

“Maybe it’ll be all right if we dry it out. I’ll take the back off and see,” says Conor. But we both know it won’t be all right.

“It’s broken, Conor.” Thick, painful tears crowd behind my eyes. Dad helped me to choose the watch, but he didn’t choose for me. The shop assistant had laid my three favourites out on the counter. A watch with a blue face and gold hands, a silver watch on a silver wristband, and this watch. My watch. Dad waited and didn’t say anything while I tried them all on again, for the third time. I held my wrist out to see how each one looked, and then I knew. This one was mine. I loved it. But it was the most expensive of the three. I took it off and put it down.

“I think I like the blue one best,” I said. I’d looked at the price labels, and I knew that was the cheapest one. But guess what Dad did then? He picked up the one I liked best and said, “Don’t look at the prices, Sapphy. You only have one birthday a year. It wasn’t the blue one you liked, it was this one.”

“How did you know, Dad?”

“You can’t fool me. I know you too well, Sapphy.”

He knew me too well, because we were alike. Me and Dad, Mum and Conor. It wasn’t that I loved Dad more than Mum, but—

“Don’t cry, Saph.” Conor puts his arm round my shoulders. “You didn’t mean to break it. But listen. You mustn’t come down here and swim on your own. You know we promised Mum we wouldn’t.”

Mustn’t come down here and swim—Indignation shocks my tears away. “What about you? Look at you, your hair’s all wet. You’ve been swimming with that girl, haven’t you?”

“What girl?”

I stare at him. “What girl? The girl who was sitting on the rock talking to you, of course. The girl with long hair like mine.”

Conor looks at me with the elder-brother look I hate. “How could you see her hair, if we were right over on the rocks?”

“I could. I could see her quite clearly.”

“The trouble with you, Saph, is that you see one thing and then you imagine something else.”

“I don’t. I don’t make up stuff. I used to when I was little, but I don’t now.”

“If you say so.”

“I don’t, Conor. Not much, anyway. You’re only saying that to stop me asking about her.”

“All right then. I went swimming after I cleaned out the shed. Maybe I should have told you I was going, but I didn’t. Just for once I wanted…”

I feel cold inside from fear of what he’s going to say. What did Conor want, that I couldn’t give him?

“…I don’t know,” goes on Conor, as if he’s talking to himself. “I wanted some space, I suppose…”

“Oh.”

“And then, after I’d been swimming, I sat on the rocks to get dry. End of story.”

“But Conor – it was this morning that you cleaned out the shed. It’s way past seven o’clock in the evening now. Probably past eight. Mum went to work hours ago. You’re telling me you’ve been here swimming for seven hours?”

“What?” Conor seizes my wrist and stares at the face of my watch.

“It stopped when I went into the water,” I say.

“It can’t be that late. You must have been messing about with your watch.” He shakes my wrist as if the hands of the watch might suddenly run backwards, to match the time he thinks it is.

“Get off me, Conor. It’s evening, can’t you see that? Look at the sun. Look how low it is.”

Conor stares around. He gazes at the mouth of the cave, where the sun is low and golden as it sinks towards the horizon. I watch him realise that I’m telling the truth.

“Maybe I fell asleep,” he says slowly. He looks lost, confused, not like my brother Conor at all.

“You were talking to someone. I saw her. She must have gone off across the rocks,” I say, but this time I say it quietly, not because I want to win an argument with Conor, but to make the truth clear. And this time Conor doesn’t answer.

“Who was she?” I ask, not even expecting him to tell me. And he doesn’t. Conor’s face is pale. Tired out, the way you’re tired out after a long day in the sea. He doesn’t want to talk. Side by side, we walk back up the sand, towards the rocks, the boulders, the way that leads home. I feel shaky all over. There was a girl there, I know there was. One minute she was sitting on the rocks with Conor, and then she was gone.

In bed that night I lie awake. Conor’s upstairs in his loft room. He can’t climb down the ladder without me knowing. I’m afraid to fall asleep in case he creeps past me, down the stairs and out of the cottage. But why would Conor want to do that? I can’t think of a reason, and yet I can’t stop being afraid.

There was no reason for Dad to leave us, either.

I know Conor’s not asleep yet, because a minute ago I heard his feet stepping lightly across the floor above me, towards the window. The slap of bare feet, and then silence. He’s by his window, looking out towards the sea. I know it for sure. My eyes are stinging with tiredness but I can’t let go and drop into sleep. Not yet, not until Mum comes back.

We both promised Mum that we would never go off swimming alone in the cove. It’s so quiet and lonely there that if anything happened, there would be no chance of help. We’ve always kept our promise, until today. It wasn’t just Conor who broke it, either. If I hadn’t seen him on the rock, I would have gone on walking deeper into the water, with the sea pulling me like a magnet.

How far would the sea have pulled me? Maybe there’s sea magic too, the same as Dad once said there was earth magic. Granny Carne’s magic was mostly benign, Dad said. But what about the sea’s magic? The sea’s strong, and wild, and if you make a mistake the sea will make you pay. Sometimes you pay with your life.

Dad used to say that the sea doesn’t hate you and it doesn’t love you. It’s up to you to learn its ways, and keep yourself safe.

But I didn’t even think about keeping myself safe today, down at the cove. All I wanted was to go with the tide. I didn’t even think of Mum or Conor, because the sea was pulling me so hard.

Is that how Conor felt? Did he forget about all of us, so that hours passed like minutes? He was talking to that girl. He was. I didn’t imagine it. She was wearing a wetsuit, and her hair was long and wet and tangly, hanging over her shoulders and hiding her body. They were laughing and talking. She and Conor didn’t look as if they’d just met for the first time.

My watch! Mum will go crazy when she finds out that my watch isn’t working any more. She said it was too good for everyday, and I should put it away and only wear it on special occasions.

“Dad said I could wear it every day,” I argued. In the end Mum agreed.

“But you’d better look after it, Sapphy. You can be so careless.”

She sounded like my school report. Good work is spoiled by carelessness. Sapphire needs to concentrate, and stop daydreaming in class.

Mum said, “It’ll be a miracle if that watch is still on your wrist in six months’ time, Sapphy.”

“It will be.”

“Good. I’m hoping you’ll prove me wrong.”

Mum was wrong. My watch is still on my wrist, and more than a year has passed. Maybe she won’t notice that it isn’t working any more.

Conor’s up there in his loft room, not moving, not sleeping, staring out of the window. All I want to hear is the tread of Conor’s bare feet back over the floorboards to his bed. But he stays at the window. I pull my curtain open, and see that the moon is rising. Even ordinary things are starting to look mysterious. The thorn bushes look like bodies that have been bent and bowed. Those white towels on the washing line that I forgot to bring in look like ghosts. It is so bright that you could find the path down to the cove quite easily by moonlight. Sometimes the moon makes a path on the sea and it looks real and solid, as if you could walk out on it to the horizon.

I hear a creak. It’s Conor, pushing his window wide. Maybe I should go up to him? No. He’ll be angry. He’ll think I’m following him around. But I’m not. I’m just looking out for him. Trying to look after him, the way Dad said we had to look after each other.

“As long as you two look out for each other, you’ll be safe enough.”

I can hear Dad’s voice saying those words, exactly as if he was here in the room. If I shut my eyes, it will be almost as if he were here…

No. If I’m not careful I’m going to fall asleep, and then Conor could creep down the ladder and out of the house, without me knowing. I sit up in bed and very quietly switch on the little lamp by my bed. As soon as I hear Mum’s car up by the gate, I can quickly turn the light off before she opens the gate and drives down the track and sees it.

On my bedside table there is a green and silver notebook which I used to keep my diary in. I’ve torn out the diary pages, because they were all about things that happened a long time ago when our life was different. Now I write lists.

I pick up my favourite black and silver pencil.

List of things that might have happened to Dad:

1. One of those factory fishing boats came too close inshore. Dad’s boat got dragged in its net and he was drowned. They untangled his boat and dropped it overboard so no one would have any evidence, because it’s against the law to be fishing where they were fishing.

This is what Josh Tregony says his dad says.

2. There was a freak squall and the boat went down.

This was one of the things they suggested in The Cornishman, but everyone remembers that it was flat calm that night.

3. Dad never went in his boat at all. He took her out as far as the mouth of the cove then he let her go on the tide and he swam back and went off another way. He had his own reasons for wanting folk to think he had drowned.

Someone said this in the Miners’ Arms. I heard it from Jessie Nanjivey, in my class. She said Badge Thomas said he would ram the teeth of the man who said it right down his throat if he opened his mouth again. The man was from Towednack, Jessie said. No one who knows Dad would ever believe it. He would never let the Peggy Gordon go on the tide. He loves her too much.

4. “Was your husband worried about anything? Debts? Problems at work? Did he seem depressed or unlike himself? Had he been drinking?”

These are some of the questions that the police asked Mum. Conor and I guessed what the police were trying to find out, but it was all rubbish. Dad was happy. We were all happy.

5. “You remember what happened to that other Mathew? Could be it’s the same thing come again.”

“You don’t really reckon, do you?”

“Well, they do say—”

This was Mrs Pascoe and her cousin Bertha talking in the post office stores. They saw me come in and they bit off the rest of what they’d been going to say. I hung around the birthday-card stand pretending to choose one, but the women just paid for their stuff and went out. They could have been talking about something else, but I don’t think so. I could see from their looks that they’d been talking about us, and there’s no other Mathew around here except Dad. That other Mathew – what did they mean?

I look down at the list I’ve written, and cross out three and four straight away. That leaves one, two and five. Josh Tregony’s dad told him that a factory fishing trawler did once pull down a small boat off the Scottish coast. The small boat got caught in the nets and dragged down, and the fishermen drowned. So maybe it could happen here. I don’t believe the freak squall theory. I remember that night too well, and how flat the sea was. So number two can be crossed out as well.

That leaves one and five. I don’t understand five at all, so maybe I’d better leave it on the list for the time being, until I find out more.

Suddenly I hear three sounds at once. The crunch of Mum’s tyres on the stony track up by the gate. The creak of a window shutting upstairs. The slap of Conor’s feet on the boards as he runs back to bed.

I slam my notebook shut, snap off the light, and dive under my duvet.

CHAPTER FIVE (#ulink_1cec7ce0-ab94-5c30-8d8b-03263302f384)

When I wake the next morning, there’s heavy white mist outside my window. I can’t even see the garden wall. I push my window open and lean out. There’s a mournful lowing sound, like the moo of a cow who has been separated from her calf. It’s the foghorn, calling to warn the ships.

So many ships have run aground and broken up on the rocks around here. Dad used to tell me a long list of their names: the Perth Princess, the Andola, the Morveren, the Lady Guinevere. Some of the wrecked ships were homeward bound from wars more than two hundred years ago, Dad said. You can still find driftwood from ships that sailed to fight Napoleon and never reached home again. Dad once showed me a piece of driftwood with a hole where a ship’s brass nail would have fitted.

I held it up and put my finger over the nail hole. I tried to imagine what it was like when the ship sank. The noise of the wind screaming and the waves pounding. Men would yell out orders on deck, trying to save the ship. But the wind and current were stronger than the power of the men, and the ship was driven on to the black spine of the rocks.

The rocks ripped the hull and water gushed in, on top of the people who were struggling to escape. There was nowhere to go, except into the wild black water.

Boys Conor’s age worked on those ships. Maybe they climbed the masts as high as they could, trying to save themselves. They clung to the spars as the ship tossed this way and that like a horse that falls at a jump and breaks its back.

They had no chance. The sea knows how to break up any ship. Those rocks are too far out for people on shore to throw lines and save them. In that raging sea you could never launch a boat for rescue.

The foghorn lows again. Danger, it says. Keep away. Danger. I hope the ships are listening today.

Mum’s up. I can hear her banging around in the kitchen. No sound of Conor.

My heart jumps in fear. Barefoot, I tiptoe to the loft ladder. I grasp its sides and climb up as quietly as a squirrel, high enough to see Conor’s bed.

He’s there. I can see the back of his head poking out of the top of the duvet. He’s fast asleep.

I climb down the ladder, go to the bathroom and then pull on my jeans and a sweatshirt. If I’m quick, I’ll get the chance to talk to Mum before Conor wakes up. Maybe I’ll be able to tell her what happened yesterday – ask her what we can do—