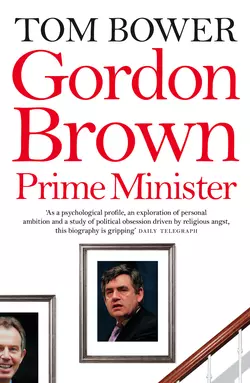

Gordon Brown: Prime Minister

Tom Bower

The gripping inside story of Gordon Brown’s rise to become Prime Minister.Gordon Brown’s arrival at the Treasury in May 1997 was greeted with great excitement – not to mention anticipation. Officials of every rank looked on expectantly to see what miracles the chancellor would work. And so, as Master of the New Era, Brown created relationships across every Whitehall department and extended his influence to every aspect of government. He brought into effect the most important budgetary changes of the past decade: the commitment to Private Finance Initiative, which altered infrastructure from the London Underground to the NHS and state schools; the management of the Inland Revenue; the increase in taxes; and the demise of Britain’s pension funds.In this gripping and fully updated biography, reissued to coincide with Brown’s assumption of Tony Blair’s mantle, best-selling author Tom Bower documents the rise to power of a driven and complex politician, and exposes how the ambitions of the Labour Party’s leader-in-waiting will affect the country for decades to come.

TOM BOWER

GORDON BROWN

PRIME MINISTER

DEDICATION (#ulink_03c8da91-0367-5ab9-a32d-d798b56d122c)

To Sophie, with love

CONTENTS

Cover (#uff59d981-143e-5f71-8596-c204ab28aa68)

Title Page (#ua7c102fd-8ccb-5b15-87c7-487c7c92543f)

Dedication (#ufce1eb85-9655-50b0-8ef0-20d416509688)

Introduction (#u54f9474b-ea77-5c10-b3be-cf284e7bdbfb)

1 Ghosts and Dreams (#u9d4c106f-8142-5752-8881-563a7b909046)

2 Metamorphosis (#u23cd510d-c098-5325-8a57-91a50fd1160d)

3 Turbulence (#u018c6ecb-723f-5ddc-928e-120256e7f555)

4 Retreat (#u8a75548e-169a-5f0d-a1d3-8a336184bfaf)

5 Seduction (#litres_trial_promo)

6 ‘Do You Want Me to Write a Thank-You Letter?’ (#litres_trial_promo)

7 Fevered Honeymoon (#litres_trial_promo)

8 Demons and Grudges (#litres_trial_promo)

9 Enjoying Antagonism (#litres_trial_promo)

10 Turmoil and Tragedy (#litres_trial_promo)

11 Revolt (#litres_trial_promo)

12 Aftermath (#litres_trial_promo)

13 Bloodshed (#litres_trial_promo)

14 Coup (#litres_trial_promo)

Index (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Source Notes (#litres_trial_promo)

Praise (#litres_trial_promo)

By the Same Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

INTRODUCTION (#ulink_eaab8668-60ce-50bc-8d74-6699cddc249a)

Their laughter was raucous. Seated in the Club section of the British Airways aircraft, the ten men were bonded by their love of football and their anticipation of a laddish weekend in Rome. Five months after the general election, the new Chancellor of the Exchequer was laughing with his intimate gang. There was much to celebrate.

On Saturday, 11 October 1997, England was playing Italy in a qualifying match for the World Cup. The valuable tickets for the game had been obtained for the group by Geoffrey Robinson, the paymaster general, as a favour to Gordon Brown, who was seated in the front of the jet. The prospect of football, beer and banter in Rome appealed to the former schoolboy footballer. The game was a male’s world, an emotionally satisfying conclave excluding women. The weekend would also be an opportunity to develop relationships with journalists, whose sympathetic reports about his successes would enhance his reputation and help his dream to become Britain’s prime minister. Brown, the host of many noisy parties during and after his student days in Edinburgh, enjoyed the mixture of politics and sport.

The invitations to the journalists had been issued by Charlie Whelan, the chancellor’s sparky press spokesman, who was seated near Brown. Over the previous years Whelan had regularly offered friendly journalists tickets to special football matches and issued invitations to memorable parties before international fixtures in Robinson’s flat at the Grosvenor House Hotel in Park Lane. ‘Oh, Geoffrey,’ quipped Brown as they flew over Tuscany, ‘your villa is down there. We should have a campaign: one villa one vote.’ The reference to the villa controversially loaned to Tony Blair and his family during the summer triggered more laughter. Brown had been in good form ever since they assembled at Heathrow. ‘What’s the difference,’ he had asked as they waited for the plane, ‘between Jim Farry [the chief executive of the Scottish Football Association] and Saddam Hussein? One is an evil dictator who will stop at nothing, and the other is the leader of Iraq.’ The banter was joined by Ed Balls, the chancellor’s personable and intelligent adviser, and the fourth of the quartet – Brown, Robinson, Balls and Whelan. Balls’s eminence in the Treasury was resented only by the envious and the defeated. The thirty-year-old was the intellectual guide of the chancellor’s conversion from a traditional socialist to the mastermind of New Labour’s appeal to the middle classes. Since Labour’s landslide victory Balls had become guru, gatekeeper and ‘deputy chancellor’ in the Treasury.

The four had unashamedly fashioned their capture of the Treasury as storm troopers assailing a conservative bastion, revolutionaries expelling the old guard. Over more than a decade Gordon Brown had plotted and agonised to achieve that coup. Disputes and distress had marred the route to 11 Downing Street, and five months after his victory the new, unconventional inhabitants of Whitehall incited malicious gossip about the introduction of bull market tactics into Westminster politics, prompting Blairites to accuse Brown of behaving like a Mafia godfather, an accusation he resented.

The only unease among the six journalists was caused by their Club class tickets, each costing £742. Geoffrey Robinson had privately settled the account, leaving a suspicion that the journalists would not be pressed to repay. His guests briefly considered the millionaire’s motives. Robinson’s ebullience made the trip feel like one of those louche jamborees organised by public relations companies for anxious clients. His fortune, earned in suspicious circumstances and concealed in offshore banks, had financed Brown’s private office before the election. For any politician to be associated with Robinson provoked questions. The journalists judged that the chancellor was not suspicious about the motives of their host, whose generosity had relieved the Scotsman’s social isolation in London. Nevertheless, before the jet landed, some resolved that regardless of Charlie Whelan’s inevitable scoffs, their fares would be reimbursed, with a request for a receipt.

The laughter halted. Gordon Brown, dressed in his customary dark suit, white shirt and red tie, fumed, ‘Do you know they’ve sold the Scotland match against Latvia to Channel 5, and only half of Scotland has Channel 5?’ The admirer of Jock Stein had travelled to see Scotland play in Spain during the 1982 World Cup, and was dogged by a grievance about the day’s other qualifying match. The gripe erupted again after the landing at Rome airport.

The privileges of political office had been snatched by the chancellor’s party. On the instructions of Sir Thomas Richardson, the British ambassador, the embassy’s economic secretary, Rob Fenn, welcomed the group at the airport. But rather than drive direct to the embassy, Brown asked Fenn whether he knew anyone in Rome who subscribed to Channel 5. ‘I’ve got to see the Scotland – Latvia match,’ he said. After frantic telephone calls, Peter Waterworth, a first secretary, was unearthed. ‘His mother gave him a Sky subscription for his birthday,’ reported Fenn with relief. ‘Channel 5 comes with the card.’ ‘Well done,’ gushed Brown. Robinson beamed. A brief diplomatic chore over lunchtime had been arranged with Carlo Azeglio Chamoi, the Italian finance minister, to justify the trip. After that, the pleasure could start.

‘Latvia, we love you,’ chanted a group of England fans, spotting Brown step from the ambassador’s car in the centre of Rome. Brown smiled back. Public recognition elated the congenitally clandestine bachelor. Football’s tribalism was a bond, and he assumed that Waterworth, a Manchester United fan from Belfast, would welcome a Scottish fan in his living room. ‘Hello, I’m Gordon Brown,’ smiled the chancellor as Cathy Waterworth opened the door. ‘I’m so grateful that you’ll have us,’ he said, leading thirteen people into the flat before his putative hosts could have second thoughts. Geoffrey Robinson immediately assumed the role of waiter, ferrying bottles of Peroni beer from the fridge at the far end of the flat to the chancellor, already hunched up close to the television, revealing the handicap of his single eye. Preoccupied, Brown uttered only a few comments throughout the match. At half-time he disappeared to be interviewed by a journalist for Monday’s newspaper. Robinson used the opportunity to look at Waterworth’s oil paintings. ‘My father’s the artist,’ explained the host. ‘Would you sell me that one?’ asked the paymaster general. The doorbell rang. A journalist returned with a bunch of flowers for Cathy. When the second half started, Robinson resumed his duties as waiter, and as Scotland’s 2–0 victory seemed assured, the atmosphere became light-hearted. ‘Great,’ announced Brown at the end. After more jokes, he bade farewell. He looked forward to the live match later that night.

The next stop was the British embassy. ‘I wonder how much we’d get if we flogged this lot,’ chortled Whelan in his south London accent as they walked into the marbled, ornately furnished building. The chancellor smiled at the joke directed at Robin Cook, the foreign secretary, one of Labour’s tribe whom Brown, during his fraught journey up the party’s hierarchy, had grown to loathe. They were joined by Stuart Higgins, the editor of the Sun, Tony Banks, the minister for sport, and Jack Cunningham, the minister of agriculture. Neither of the politicians was a ‘Brownite’, and their politeness towards the chancellor was noticeably diplomatic. Standing in the corner was Sir Nigel Wicks, the Treasury’s second permanent secretary. ‘Are you going to the match?’ Wicks was asked. ‘No,’ he replied hesitantly. ‘Why?’ ‘Prudence.’ ‘What?’ ‘I’m here on business, and I would not want my presence in Rome to be misinterpreted.’ The Treasury, some speculated, had contrived the visit to the Italian finance minister as a fig leaf to justify the junket. The final guest, the genial former Manchester United star Bobby Charlton, was uniquely guaranteed Brown’s affection.

Relationships were important to Gordon Brown. His unswerving loyalty to family and friends had marked him as a clan chieftain. The admiration and love he attracted was contrasted with his ferocious hatred of others. ‘Peter Mandelson is in Rome,’ the ambassador told Brown while the champagne was poured. ‘But he returned to London rather than watch the match.’ The chancellor’s relief was unconcealed. His fraught relationship with his former friend was a source of widespread gossip.

The brief visit to the embassy mirrored the conflicts of interest, personalities and policies swirling around every nuance of the chancellor’s hectic life. Just as renowned as his intelligence, education and shrewdness were his vendettas. ‘Never hate your enemies,’ said Michael Corleone, the son of Mario Puzo’s Godfather. ‘It affects your judgement.’ Gordon Brown ignored that advice, but did embrace Corleone’s confession to his lawyer: ‘I don’t feel I have to wipe everybody out, Tom. Just my enemies.’ Surrounded by his intimates, the Godfather expected loyalty and obedience towards himself. Those who thwarted his ambitions were despised and occasionally destroyed. His justification was faultless: his beloved party and his ambition required submission to his agenda. In return for his trust, his ‘family’ honoured his requirements.

Driving in a minibus from the embassy past the Colosseum, the home of bloody gladiatorial contests, towards Rome’s Olympic stadium for the football match, the chancellor might have reflected upon the ancient building’s symbolism. Two thousand years earlier, only the fittest survived, and even at the moment of glory, the bloodied victor could be ravaged by the spectators’ dissatisfaction. His party’s antics back home resembled ancient Rome’s lack of generosity. The pernicious undercurrents in Westminster often turned friend into foe. Over the years, Gordon Brown had accumulated many enemies. To win the ultimate prize required a new strategy. Inviting the journalists to Rome was another step to win favour for his inheritance of the premiership.

At the stadium, Brown was seated with Carlo Azeglio Chamoi. The match was enjoyable but by the end at 10.45 p.m., both were disappointed by the goalless draw. Gazing down from the directors’ box, Brown watched as Italy’s supporters and some of the 16,000 England fans began fighting. With drawn batons the police were charging the Britons. Patiently, Brown waited for two hours in the minibus until the six journalists could leave the stadium. Robinson had fretted that his reservation at Harry’s Bar for a lobster and champagne dinner would be cancelled, but the famous restaurant loyally waited for the party, as did the soprano hired to sing for them. The bill for the enjoyable dinner was paid by Robinson.

After the group’s return to London, the trip attracted some curiosity. For a time the presence of the journalists with the chancellor was suppressed by some newspapers, and when, seven weeks later, Geoffrey Robinson became embroiled in a scandal about his financial dependence on an offshore tax haven, some of those journalists who had accepted his hospitality were inclined to vouch for his probity. Consumed by self-righteousness, Gordon Brown disparaged those criticising his paymaster, and steadfastly resisted any public admission of Robinson’s wrongdoing. Concessions, he knew, signalled weakness. Thanks to Brown’s support, Robinson would survive the first accusations of sleaze. But the lifebelt caused many to puzzle about the chancellor’s psychology. His defiance was forged, some suggested, during his Scottish childhood in order to camouflage his spiritual torment. Others speculated why one character simultaneously aroused extremes of sympathy and outrage. Gordon Brown himself volunteered few clues. Incapable of self-analysis, he zealously sought to prevent outsiders from penetrating the origins of and reasons for his emotions. An unmentioned spirituality certainly lurked among the foundations of his life. The possibility of entering the priesthood had never featured among his ambitions, yet the conflict between good and evil had dominated his formative years. The mystery was his journey from his childhood credo of God and love to the less forgiving characteristics that would dominate his adulthood. His ostensible compassion for humanity confused the search for clues about that transition yet bequeathed the riddle: Gordon Brown, saint or sinner?

ONE Ghosts and Dreams (#ulink_0b36ba3f-5982-5b0c-83aa-d71c6144c934)

The stench of linseed oil and coal drifting up the hill obliterated the salty odour of the cold sea waves crashing just four hundred yards from his family’s large stone house. Two linoleum factories were part of Kirkcaldy’s lifeblood, just as the small town’s financial survival relied upon the local coalmines. Both were dying industries, threatening new unemployment in the neighbourhood. The men of Fife profess to be self-contained, but are vulnerable to their environment. Kirkcaldy’s stench, grime and decay shaped Gordon Brown’s attitude towards the world.

Kirkcaldy in the 1950s could have been a thousand miles from Edinburgh, although the elegant capital lay just across the Firth of Forth. Gordon Brown’s home town was shabby, and the townspeople were not a particularly united community. John Brown, his father, the minister at St Brycedale Presbyterian church, struggled unsuccessfully to retain his congregation. Some had permanently renounced the Church, while others had moved to the suburbs, abandoning the less fortunate in the town. Outsiders would have discovered nothing exceptional about John Brown’s ministry in Kirkcaldy’s largest church. His status was principally attractive to those at the bottom of the heap, who called regularly at Brown’s rectory – or manse – for help. The preacher of the virtues of charity was willing to feed the hungry, give money to those pleading poverty, and tend the sick. Some would smile that John Brown was an unworldly soft touch, giving to the undeserving, but his generosity contrasted favourably with Fife’s local leaders. There was little to commend about the councillors’ failure to build an adequate sea wall to protect the town from the spring tides of 1957 and 1958. During the floods, young Gordon Brown helped his father and his two brothers distribute blankets and food to the victims, proud that his father became renowned as a dedicated, social priest. ‘Father,’ he later said, ‘was a generous person and made us aware of poverty and illness.’ The dozens of regular callers at the house pleading for help persuaded Brown of the virtues of Christian socialism, meaning service to the community and helping people realise their potential. Living in a manse, he related, ‘You find out quickly about life and death and the meaning of poverty, injustice and unemployment.’ The result was a schoolboy bursting to assuage his moral indignation.

Friends and critics of Gordon Brown still seek to explain the brooding, passionate and perplexing politician by the phrase ‘a son of the manse’. To non-believers, unaware of daily life in a Scottish priest’s home, the five words are practically meaningless. Only an eyewitness to the infusion of Scotland’s culture by Presbyterianism’s uncompromising righteousness can understand the mystery of the faith. Life in the manse bequeathed an osmotic understanding of the Bible. Under his father’s aegis, Gordon Brown mastered intellectual discipline and a critique of conventional beliefs. In a Presbyterian household, the term ‘morality’ was dismissed as an English concept, shunned in favour of emphasising ‘right’ and ‘wrong’. Even the expression ‘socialism’ was rejected in favour of ‘egalitarianism’. At its purest, Presbyterianism is a questioning tradition, encouraging a lack of certainty, with a consequent insecurity among true believers brought up to believe in perpetual self-improvement. ‘Lord, I believe,’ is the pertinent prayer. ‘Help Thou my unbelief.’ Moulded by his father’s creed, not least because he admired and loved the modest man, the young Gordon Brown was taught to be respectful towards strangers. ‘My father was (#litres_trial_promo),’ he recalled, ‘more of a social Christian than a fundamentalist … I was very impressed with my father. First, for speaking without notes in front of so many people in that vast church. But mostly, I have learned a great deal from what my father managed to do for other people. He taught me to treat everyone equally and that is something I have not forgotten.’

In his sermons, quoting not only the scriptures but also poets, politicians and Greek and Latin philosophers, the Reverend John Brown urged ‘the importance of the inner world – what kind of world have we chosen for our inner self? Does it live in the midst of the noblest thoughts and aspirations?’ He cautioned his congregation and sons against ‘those who hasten across the sea to change their sky but not their mind’. Happiness, he preached, is not a matter of miles but of mental attitude, not of distance but of direction. ‘The question which each of us must ask, if we are not as happy as we would wish to be, is this: Are we making the most of the opportunities that are ours?’ The young Gordon Brown was urged to understand the challenge to improve his own destiny. ‘So let us not trifle,’ preached his father, condemning wasted time and opportunities, ‘because we think we have plenty of time ahead of us. We do not know what time we have. We cannot be sure about the length of life … Therefore use your time wisely. Live as those who are answerable for every moment and every hour.’

John Brown’s ancestry was as modest as his lifestyle. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries the Browns were tenant farmers, first at Inchgall Mill near Dunfermline, and later at Brigghills farm near Lochgelly, in the midst of the Fife coalfields. Ebenezer Brown, Gordon Brown’s grandfather, the fourth of eight children, became a farmer at Peatieshill in New Gilston, and on 26 October 1914 Gordon’s father was born in the farmhouse. Eventually Ebenezer gave up farming and became a shepherd, encouraging his only child to excel at school and to break out of the mould. At eighteen, John Brown’s efforts were rewarded by a place at St Andrews University to read divinity. After graduating in 1935, he studied for an MA in theology until 1938. Unfit for military service, he spent the war as a minister in the Govan area, along the Clyde, living among the slums and destitution of the factory and shipyard workers. Only the heartless could emerge from that poverty without some anger about society’s inequalities.

Soon after the war John Brown met Jessie Elizabeth Souter, the daughter of a builder and ironmonger in Insch, west Aberdeenshire. She was four years younger than him. Until 1940 Jessie had worked for the family business. She then joined the WRAF, working first on the Isle of Man and then in Whitehall. They married in Govan in July 1947. Their first child, John, was born in 1948. James Gordon, their second son, was born in Glasgow on 20 February 1951. Three years later John Brown was appointed the minister at the St Brycedale church. Kirkcaldy was then an unknown backwater, except to historians. In the eighteenth century Adam Smith, arguably one of the world’s greatest economists and the architect of free trade, the foundation of Britain’s prosperity, lived in the town. A monument to the enemy of socialism was erected exactly opposite St Brycedale church. The juxtaposition was pertinent to Gordon Brown’s life. Not until forty years after his birth did he begin to sympathise with his fellow townsman’s philosophy. By then his reputation as an irascible intellectual was frustrating his ambitions. His inner conflict, pitting his quest for power against his scholarship, his mastery of machine politics in conflict with the protection of his privacy, had been infused by the influence of his beloved father.

‘Ill pairted’, the principal doctrine bequeathed by the teetotal father to his sons in the manse, condemned the unfair distribution of wealth in the world and stirred up his family’s obligation to seek greater equality, not least by good works and charity. The collapse of the textile and coal industries, casting hundreds in the town onto the dole, imbued a gut distaste for capitalist society in Gordon Brown, not least because his father taught that work was a moral duty. ‘Being brought up (#litres_trial_promo) as the son of a minister,’ he recalled, ‘made me aware of community responsibilities that any decent society ought to accept. And strong communities remain the essential bedrock for individual prosperity.’ Unspoken was the Scottish belief in superiority over the English, and the Presbyterian’s sense of pre-eminent differences with Anglicans – both compensations for surviving as a minority.

Helped by Elizabeth Brown’s inheritance of some small legacies, the Browns were middle class. Their financial advantages over the local miners and factory workers spurred the father to encourage his children to conduct their lives with a sense of mission, duty and benign austerity. Any personal ambition was to be concealed, because the individual, in John Brown’s world, was of little interest, and personal glory was, history showed, short-lived. Rather than bask in the prestige accorded to his office, he preached that his children should be more concerned by the legacy they bequeathed to society. The son of the manse was expected to suppress his ego. That exhortation, repeated constantly throughout his childhood (he attended his father’s church twice on Sundays), imposed upon Gordon Brown a lifelong obligation to answer to his father’s ghost.

Any austerity was, however, tempered by love. Elizabeth Brown was not as strong an influence as her husband, but she was a true friend. ‘She was always supportive,’ Brown insisted, ‘even when I made mistakes.’ At the age of thirty-seven, he was to say: ‘I don’t think (#litres_trial_promo) either of my parents pushed me. It was a very free and open family. There were no huge pressures.’ His comment was either self-delusion or obfuscation. Quite emphatically, from his youngest years, Brown was under exceptional pressure to excel, and infused with an obsession to work hard, to disappoint no one and to win. ‘What is started, must be finished,’ was a constant parental admonition to the Brown brothers. Failure was inconceivable. From the pulpit the Reverend John Brown preached that many of the young ‘are failing to think life through and are living carelessly and irresponsibly’. They forgot, he said, that regardless of any remarkable achievements on earth, ‘after death we must appear before the judgement seat of Christ’. He admonished ‘the multitudes’ who gave ‘little thought of accountability for their conduct and way of life’. Gordon Brown was warned about a day of reckoning: ‘With many, judgement begins and ends with themselves and they reckon not on any judgement from elsewhere. Such live to please themselves and not to please others, even God.’ John Brown urged his congregation to look forward to His commendation: ‘Well done, good and faithful servant, enter into the joy of thy Lord.’

Gordon Brown’s blessing, or possibly misfortune, was his stardom. From his earliest years he was praised as outstanding, destined to outclass his contemporaries. Like all Scots children, he was embraced by the country’s excellent system of state education. At Kirkcaldy West, a primary school close to the linoleum factory, he was taught the three ‘R’s by repetition, writing with pencils on slate boards, with a wet rag to wipe off his daily work. He devoured books and, thanks to an aunt, a music teacher, appreciated classic literature. The teachers instantly recognised his unusual intelligence, reporting that he was a year ahead of other pupils in maths and reading, as was one other boy, Murray Elder, who would remain his friend in Scottish Labour politics and Westminster until the present day. At the age of ten, Brown and Elder were enrolled at Kirkcaldy High School, the town’s grammar school, in an educational experiment to fast-stream the town’s brightest schoolchildren by intensive learning.

The High School was a genuine social mixture. The children of dustmen, miners and millionaires were educated together, ignoring their social differences. But the searing recollections of the parents of the poorer children about the days before the creation of the NHS made a lasting impression on Brown. Their elders spoke of the poor abandoning treatment in hospitals when their money was spent, and asking doctors about the cost of visits and medicine before deciding whether their finances were adequate for them to receive treatment.

Ferociously clever, although not the cleverest in the class, Brown never appeared as a swot. Rather he was known as ‘gregarious and jolly’, and the quickest to provoke laughter with a snappy, funny line. ‘The banter and wisecracking that would go on between the boys was great,’ recalled a former class friend. Brown’s passion was sport. He excelled at tennis, rowing, sprinting, rugby and especially football. Around the time he heard the radio commentary of Scotland’s 9–3 humiliation by England in 1961, he resolved to become a professional footballer. On Saturdays, he was seen at the ground of Raith Rovers, the local football team, selling programmes with John, his elder brother, to earn pocket money before cheering the local side. Combining work and pleasure was his father’s doctrine. The most notable result was the newspaper Gordon produced in his pre-teens with his brother and sold for charity. John was the editor while Gordon wrote the sports reports, and later added commentaries about domestic politics. In successive weeks (#litres_trial_promo) in 1964 he welcomed Harold Wilson’s election, interviewed an American space pioneer, described the persecution of Jews and supported Israel’s existence, and explained the background to crises in the Middle East and Southern Rhodesia. Justifying the new state of Israel was a particular theme encouraged by his father. Brown revealed himself not as precocious, but as a sensible and informed youth. His love of history and politics was partially influenced by ‘Tammy’ Dunn, the school’s left-wing history teacher, although his historical hero in the fourth form was Robert Peel, the nineteenth-century Tory prime minister praised for placing principle before party. In a competition organised by the Scottish Daily Express to write an essay anticipating Britain in the year 2000, Brown won a £200 prize. He predicted that Scotland’s inequalities would eventually be removed: ‘The inheritance of (#litres_trial_promo) a respect for every individual’s freedom and identity,’ he wrote, ‘and the age-long quality of caring, both transmitted through our national religion, law and educational system and evident in the lives of countless generations of our people, makes Scotland ideal for pioneering the society which transcends political systems.’ Forty years later he remained faithful to what he called those ‘absolutely basic’ visions and values.

In 1963 Brown witnessed real politics for the first time. Aged eleven, he followed the election campaign in Kinross and Perthshire of Sir Alec Douglas-Home, the prime minister. Ill-health had forced Harold Macmillan to resign, and his successor Earl Home had revoked his peerage to lead the Conservatives in the House of Commons. After a day following the politician across the constituency, the impression of a politician making the same speech at every venue, recalled Brown, was ‘awful’. He was particularly struck by Home’s response to a question of whether he would buy a house in the constituency. No, replied Home, he owned too many houses already.

At fourteen Brown took his ‘O’ levels, and under the fast-track experiment was scheduled one year later to take five Highers, a near equivalent of ‘A’ levels. He was a year ahead of his age group. His reputation was of an outstanding student and sportsman, particularly a footballer, whose conversation, magnetising his class friends, made him the centre of attention. Despite his popularity in the mixed school, he stood back from the girls. At the popular dances organised by his older brother in the church hall, Gordon did not bop, and disliked the waltz and quick-step lessons. No one recalled him ever speaking about girls. Even during a hilarious school trip to Gothenburg, his behaviour was impeccable. Some believed that the arrival every week of his father as school chaplain to preach to the children inhibited him. As predicted, at fifteen, he scored top marks in his Highers and qualified for university. He had survived the intensity of the ‘E’ experiment, but was troubled by the casualties among other ‘guinea pigs’ who, having collapsed under the pressure, were depressed by having failed to gain a place at university and being deprived of an opportunity to try again. Sensitive to the raw inequalities of life, uncushioned in Scotland’s bleak heartlands, he sought a philosophy which promised change.

At that age most teenagers rebel against their parents’ values, but Brown, inspired by his close family life, accepted his father’s traditionalist recipe for reform. In their unequivocal judgements of society, the Presbyterians’ solution was to empower the state to castigate the rich and to help the poor. In Kirkcaldy, Adam Smith’s philosophy for curing society’s ills by self-reliance and free enterprise was heresy. The socialist paradise promised by Harold Wilson, embracing the ‘white heat of technology’, redistribution of wealth and economic planning, was Gordon Brown’s ideal.

One irony of Brown’s registration at Edinburgh University in 1967 to read history would have been lost on the sixteen-year-old. The university was a bastion of privilege, isolated from Scotland’s class-ridden society. Dressed in a tweed jacket, grey flannels, white shirt and tie, Brown arrived with Kenn McLeod and other working-class achievers from Kirkcaldy High. While McLeod and the sons of miners and factory workers had neither the money nor the background to become involved in the horseplay of student life, Brown was introduced to the power brokers by his elder brother John.

‘This is my brother Gordon,’ John told Jonathan Wills, the editor of the student newspaper. ‘He’s sixteen and wants to work here. He’s boring but very clever.’ Brown was in heaven. The student newspaper was a cauldron of the university’s political and social activity. Within the editorial rooms he could witness heated debate and crude power-broking. Inspired by the worldwide student revolt then taking place, Jonathan Wills had begun a campaign to become the university’s first student rector. Free of the inhibitions imposed by his small home town, Brown indulged himself amid like-minded social equals. The liberation and the dream were short-lived.

Six months earlier, during a rugby match between the school and the old boys, he had emerged from the bottom of a scrum suffering impaired vision. Instinctively private, he did not complain or visit a doctor. The problem did not disappear. In a football match during the first weeks at university he headed the ball and his sight worsened. This time he consulted a doctor, who identified detached retinas in both eyes. The six-month delay in treatment had increased the damage, and there was a danger of blindness in the right eye. In the first of four operations over two years at the Edinburgh Royal Infirmary, surgeons sought to reattach the retinas. Brown was ordered to lie immobile for six months in a dark hospital ward, knowing that among the drastic consequences was the certain end of his ambition to become a professional footballer. Whatever the outcome of the operation, playing contact sports would be forbidden. During those months of darkness, with the combination of loneliness and fear described by him as ‘a living torture’, unable to read and hoping that he would not be permanently blind, Brown’s psychology changed. Sensitive to his plight and preoccupied by his ambitions, he became impatient with life’s trivialities, and resolved in future not to waste time or to suffer fools. ‘I felt such (#litres_trial_promo) a fraud,’ he later said, ‘lying in bed for hours on end when there was nothing wrong with me except that I couldn’t see.’ Irritated by medicine’s limitations, his infirmity became a blow to his self-confidence, compounding the insecurity which would bedevil his life and inspire reconsideration of his faith. In a later interview, Brown mentioned his trepidation about the predestination preached by Calvinists. ‘The idea that it doesn’t matter what you do, that you could be predetermined for damnation’ was unappealing, he explained. He disliked the concept of ‘no credit for human endeavour since all decisions are made by God. It’s a very black religion in that sense.’ By contrast, his teetotal father’s practice of good works and charity was infinitely preferable; but doubts had also arisen about that. The Presbyterian ethic – that the afterlife was not so attractive – was also unappealing. Rather than embracing religion as support for his torment, his certainty about God and the scriptures had weakened. Neither in public nor in private would he ever express thanks to God or refer to Christianity as an influence, guide or support for his life.

He rejected the paraphrase of a poem often recited by John Brown at the sickbed:

He gives the conquest to the weak,

Supports the fainting heart,

And courage in the evil hour

His heavenly aids impart.

Rather, he was influenced by a pertinent sermon of his father’s summarising the lesson of anguish and salvation: ‘Blindness is surely one of life’s sorest handicaps … For them vistas of loveliness are shut off and bring no joy and gladness.’ John Brown’s sympathy for the blind switched to rhetorical criticism of the sighted: ‘Is it not the case that many of us – yes, most of us – even though we have our seeing faculties, walk blindly through life? We notice so little when we could see so much, passing by the wonders of creation without giving them a thought … Perhaps more people suffer from blindness than we realise … Through an over-concentration on trivialities, they have lost sight of the things that really matter.’

Any trace of his son’s dilettantism was expunged. After six months in hospital, there was relief that one eye was saved. The left, dead eye permanently changed Brown’s appearance. His smile no longer triggered the normal facial muscles, gradually creating a slightly dour expression. At the time he spoke of the operation as a success, but he would tell a friend years later, ‘The operation was botched. Everyone can make mistakes.’ He particularly recalled the surgeon’s quip, ‘Well Gordon, we’ll have another bash.’

In spring 1968 he courageously resumed his studies and re-engaged in university life. The seventeen-year-old self-consciously hid any suggestion of impairment and the psychological consequences of six months’ darkness. Compared to the shy fresher introduced by his brother to Jonathan Wills as a potential contributor to the student newspaper, Brown now displayed more self-confidence than previously. Propelled by a single-minded lust for success, in one way he resembled Willy Loman in Arthur Miller’s play Death of a Salesman: ‘He had the only dream you can have – to come out number-one man.’ In effect, Brown sought control over others. Within weeks, most students at the university were conscious of an exceptional undergraduate in their midst.

The contrast between the outstanding student diligently pursuing his degree and the near squalor of his first home in the Grassmarket, just behind Edinburgh Castle, and later his second, larger home in Marchmont Road, entered the university’s folklore. At first the rooms at 48 Marchmont Road were shared with six or seven other students as a statutory tenant, but after fifteen years he would buy them for a bargain price. With some pride Brown would confirm his chronic untidiness, retelling a story of a policeman reporting a burglary at his flat. ‘I have never seen such mindless vandalism in thirty years in the force,’ said the police officer of the chaos. Brown surveyed the scene. ‘It looks quite normal to me,’ he replied. Those sharing his flat tolerated not only the anarchy but also one unusual tenant who one afternoon caught a burglar entering through the skylight. Instead of calling the police she invited the intruder to stay, for an affair lasting several weeks. Her room was subsequently occupied by Andrew, Gordon’s younger brother, a keen party host. Those who ever voiced a suspicion that Andrew was riding on his elder brother’s achievements were promptly cautioned. ‘Please don’t hurt me by criticising Andrew,’ Brown once told Owen Dudley Edwards, his university tutor. ‘Criticise me, but not Andrew.’

Politics was his passion, and his political stance was set in concrete. He joined the Labour Party in 1969, and while growing his hair long, ignored the fashionable far left, refusing to join the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND) or to join the movement for greater Scottish independence following the discovery of oil in the North Sea. He was never seen smoking pot or uncontrollably drunk, even as the host of his frequent parties. The dozens who regularly crowded into the flat to drink beer and eat dry cubes of cheese at the end of toothpicks, influenced by the turbulence in England during the sixties, fashioned themselves ‘The Set’, convinced that they were destined to change the world, and particularly Scotland. No one could accuse Brown of conducting himself like Adam Morris, the ambitious undergraduate played by Tom Conti in the successful 1970s television dramatisation of Frederic Raphael’s novel The Glittering Prizes. But the more self-important of his elegant friends – like Wilf Stevenson, who hosted dinner parties – and those who joined Brown at the cinema, theatre and particularly the Abbotsford pub just south of Princes Street, regarded themselves even if inaccurately as Edinburgh’s equivalent of the Bloomsbury set, noisily quoting artists, writers and politicians. Even during his absence from those meetings, Brown’s ghost was present. ‘People liked being around him,’ recalled Madeline Arnot, a guest at his flat. ‘Everyone liked talking to him. He was at the centre of everything.’ While ‘The Set’ cast themselves in an unspoken competition as society’s future movers and shakers, the city’s working class – as remote from the students as the Eskimos – classed the boisterous elite as a gaggle of Hooray Henrys. By any measure, they were neither a golden nor a doomed generation.

The routine presence at these parties in 1970 of Princess Margarita of Romania, the eldest daughter of the exiled king, enhanced that image. Good-looking, charming and intelligent, Margarita had been introduced to Brown by John Smythe, one of the six people sharing his flat. Heads turned, it was said, whenever Margarita, of French, Greek and Romanian parentage, with a pedigree derived from the Habsburgs, Romanovs and Hohenzollerns, entered a room. The modest student of sociology and politics, who spoke English with a middle-class accent, hid her real background. Her family’s small home was near Lake Geneva, but thanks to her friendships with the king and queen of Spain, the exiled king of Greece, and Europe’s minor royalty, she was accustomed to living in mansions and palaces across the continent. Since their backgrounds were so different, Brown’s attraction to the ‘Red Princess’, as she became known, puzzled many. Some of Brown’s flatmates, who like him were becoming increasingly politically active, were irritated by the gilt-edged invitations arriving through the letterbox just as their flat was becoming the centre of a revolution. He offered no explanation when she moved into his bedroom. His silence reflected his Scottish respect for her privacy and, more importantly, his belief that intimacies were not public property. Friends, however, understood the attraction. Margarita’s looks and character were exceptional and, more important, compared to Katie, the English county girl whom Brown had been dating, she was unusually supportive. Unlike British girls, Margarita was accustomed to women offering compassion and encouragement to their men, which precisely matched Brown’s requirements. She provided maternal care, acting like a mother hen, worrying about the health of his remaining eye, deciding what he should eat (usually tuna and lettuce sandwiches), wear (the same tweed and flannels), and occasionally do. ‘He’s too busy to wash up,’ Margarita told their flatmates after the jolly communal breakfasts. Dressed in a pink nightdress, she insisted that Gordon’s life’s work was too important to be distracted by domesticities. Her pedigree had given her experience and toleration beyond her years. Her enjoyment of making decisions on his behalf appealed to a man who disliked annoying friends and who was reluctant to cause upset. But the princess would also roar in his face if his Presbyterian obduracy became irksome, deflating the pompous Fife boy.

Those who would subsequently criticise Brown for favouring intense hard work at the cost of human relationships would not have recognised him during those early months of the relationship. Margarita’s misfortune was that her boyfriend’s prevalent feminine influences were his mother and the absence of a sister. His loyalty to the ultra-conventional woman of the manse required some disguise of his lifestyle. During a visit to the flat in Edinburgh, Elizabeth Brown found some items of female underwear in the bathroom. ‘I don’t know (#litres_trial_promo) how they got there,’ exclaimed Brown with embarrassment. ‘They must have come by mistake from the laundry.’ In turn, his mother would be untroubled by his bachelorhood until, she confided to a friend, he met someone whom she could approve. Out of a sense of duty towards his parents, he agreed to a mixture of concealment and denial. Margarita faced other hurdles. Despite her unsnobbish charm, she found difficulty in supplanting the male culture of Brown’s circle. Sport was intrinsic to Brown’s life. Regularly he met a large group of friends, including many from his school, on the terraces at Murrayfield for rugby internationals or at club grounds for local football and rugby matches. Margarita was not invited. She was also excluded from his daily discussions and plots with his student allies about politics. In his second year at university he was elected chairman of the Labour Club, was the editor of the student newspaper, and was regularly sitting at the same desk in the university library, working so hard without coffee breaks that Madeline Arnot, who became a Cambridge don, later thanked him for her good degree. ‘I followed him as a role model,’ she later volunteered. Others followed Brown, albeit still a teenager, as a political leader.

In 1970, aged nineteen, disappointed like so many to have missed out on the student revolt witnessed in other cities such as Paris, he spotted an opportunity to assert student power in his own kingdom. The issue was whether the investments owned by Edinburgh University included shares in South African companies, a taboo for those seeking to destroy apartheid. The vice-chancellor Sir Michael Swann, a respected member of the Tory establishment and thus an easy man for Brown to dislike, stated publicly that the university did not invest in ‘companies known to be active in the support of apartheid’, but documents leaked to Brown by a disgruntled university administrator showed that in fact the university owned shares in many companies active in South Africa, including the mining company de Beers, which had been accused of unacceptable employment practices. Working from the student newspaper office, Brown composed a special news sheet exposing the university’s deception, electrifying the university’s community.

By accident rather than design, Brown found that midway through his studies he was leading a revolution, without realising the possible repercussions. Edinburgh’s establishment was a tight clique. Every lunchtime there was a procession of the city’s great and good from the university, financial institutions and government offices to the New Club. Their midday discussions during those days did not focus on censuring Swann for his deception, but expressed their apoplexy about the challenge to their authority by an upstart student posing as a symbol of integrity against a foreign impostor. In the long term the confrontation harmed Brown, but in the midst of the dispute his disarming manner towards the ruling class shone as a virtue.

By contrast to many of the ‘revolutionary’ students protesting in the 1960s across Britain and other parts of Europe and North America, Brown’s politics were reasoned and principled. He adhered to Labour’s traditional values. Unlike many students, he did not succumb to the emotional appeals of the Govan shipbuilders during their confrontation with Edward Heath’s government in 1971 over the closure of their yard; in fact he predicted the shipworkers’ ultimate failure. In an article for the student newspaper he criticised the ‘alternative society seekers, Trotskyite students and liberal documentary makers’ who had visited the Upper Clyde shipyards: ‘The trendies are looking in vain for their kind of revolution. While they may plan the final end of capitalism, the mass meetings, the George Square demos and the fighting talk of the stewards should not belie the real campaign on the Clyde; for this is a work-in not for workers’ control, but an attempt to save jobs, and not a demand for the abolition of private ownership.’ His analysis was probably correct, but his political inexperience blinded him to the machinations between the trade unions and the government. To his surprise, in 1972 Heath capitulated and agreed to invest in the doomed yard. Many aspiring politicians learnt from Heath’s humiliation, including Margaret Thatcher. Brown learnt the lesson twenty years later. His ragged journey to that eventual wisdom, understanding the art of political strategy and intrigue, started soon after he achieved a first class degree in history in 1972. Some would say that his was the best first ever awarded by the university.

Aged twenty-one, he embarked upon a doctorate about the Labour Party in Scotland which gradually developed over the following decade of research and writing into ‘The Labour Party and Political Change in Scotland 1918–29’. Originally he intended to explain the two-hundred-year development of labour from the seventeenth century to the emergence from the trade unions of the Labour Party in the twentieth century. His eventual thesis, less ambitiously, described Labour’s struggle to establish itself as the alternative to the Conservatives. In the course of his research he became entranced by the romanticism of Scotland’s heroic socialist pioneers – Keir Hardie, Robert Smillie, John Maclean, Willie Gallacher, John Wheatley – striving against capitalism to build the perfect society. In particular he alighted on James Maxton, a Presbyterian orator with spellbinding powers, preaching about socialism’s Promised Land. Maxton, the son of a Presbyterian headmaster closely involved in the Church, was MP for the Bridgeton seat in Glasgow from 1922 until his death in 1946. ‘He was a politician,’ wrote the great historian A.J.P. Taylor, ‘who had every quality – passion, sincerity, unstinted devotion, personal charm, a power of oratory – every quality save one – the gift of knowing how to succeed.’ In Brown’s words, Maxton, a crusading rather than a career politician, ‘had sought to make socialism the common sense of his age’. His Christian desire to promote human happiness and equality bore similarities to the sermons of the Reverend John Brown. During those years researching his PhD, Brown sought to learn from Maxton’s mistakes: the consequence of splits within a party and the occasional advantage in politics of being feared rather than loved. Scotland, he understood, produced two types of socialist – the romantic and the pragmatic. The ideal was to be the pragmatic inspired by the romantic. His test-bed was the campaign to embarrass Sir Michael Swann.

In November 1972 Brown proposed that he should be elected as rector of the university, a ceremonial office usually awarded to honour Establishment personalities. A precedent had been set the previous year with the election of Jonathan Wills, the editor of the student newspaper. To Swann’s relief Wills had resigned, but to his irritation Brown launched his first successful election campaign, a rousing operation supported by ‘Brown Sugars’, miniskirt-clad students posing as dolly girls. No one of that era would ever label Brown a puritanical Scot with a humourless, wooden face and a grating habit of repetitiously uttering identical slogans. On the contrary, he was regarded as an amusing, sincere idealist with a ‘little boy lost’ approach who articulately galvanised supporters to translate his ambitions into a convincing victory over Swann’s candidate.

With the new rector’s election came the right to chair meetings of the University Court, the ultimate authority. Excitedly, Brown exercised this power, with the intention of agitating against the university’s administrators and governors. The battle lines were drawn in a row that engulfed the campus. Outraged by the usurper, Swann sought to remove Brown as chairman. Brown responded with an appeal to the Court of Session, Edinburgh’s High Court, for a judgement against the vice-chancellor. Brown won. Swann tried one more legal ruse, but was outgunned when the Duke of Edinburgh, the university’s chancellor, influenced the University Court in Brown’s favour. Brown had appealed to Prince Philip for help through Margarita – his goddaughter.

The experience, Brown later acknowledged, was a baptism of fire. Delighting in the scandal, he sought to avoid pitfalls and to succeed by exhaustive preparation. Every event was treated as a serious occasion. His speeches could be made more effective, he learnt, by rehearsing them to his flatmates and asking them to suggest jokes. He advanced his arguments by carefully placing pertinent stories in newspapers. Patiently, he sat through tedious meetings with a pleasant, laid-back manner, displaying a high boredom threshold until he had worn down his opposition. Glorious successes were followed by miserable setbacks, but through it all the rector discovered the mechanics of power-broking and mobilising support. ‘It was quite (#litres_trial_promo) a revelation to me to see that politics was less about ideals and more about manoeuvres,’ he reflected twenty years later. His cruder assessment was: ‘The experience persuaded me that the Establishment could be taken on.’ Both conclusions conceal a deep injury. At the end of his three-year rectorship Brown had changed the University Court, but was nevertheless ambivalent about an achievement which was so blatantly irrelevant to the outside world. The cost was the accumulation of many vengeful enemies who frustrated his attempts, despite his qualifications, to be appointed a permanent lecturer at the university. In later years he would condemn those who rejected his promotion from his part-time lectureship as plotters rather than fair judges of his abilities. ‘They forced me (#litres_trial_promo) out,’ he complained in a surprised voice, ignoring all the trouble he had caused. Student politics had roused his appetite for parliamentary politics but would provide barely any preparation for his struggle to win the Labour Party’s nomination for a Westminster constituency.

Among the Scottish Labour Party’s many divisions was one between the graduates of Glasgow University and those of other universities. Brown suffered a double deficiency. His humiliation of Edinburgh’s establishment denied him one source of support, while Glasgow’s clique, which included John Smith, Derry Irvine, Donald Dewar and Helen Liddell, shunned him as unworthy to join a group convinced of its right to govern the country. In the last months of 1973 many of those activists were searching for nominations to parliamentary constituencies in time for the next general election.

Edward Heath called an election for February 1974 in an attempt to turn the nation against the coalminers, who were engaged in a strike which the Conservatives interpreted as politically motivated. Dwindling coal supplies forced Heath to impose power cuts and to reduce British industry to a three-day week. That crisis hit particularly hard in Scotland, the home of many miners led by either communist or left-wing trade union officials. The miners’ cause was emotional as well as political. The communities whose menfolk dug coal in appalling conditions were part of the backbone of the country’s working-class culture, and their suffering evoked widespread sympathy. There was every reason for Brown to forge relationships with Mick McGahey, the engaging communist miners’ leader, and Lawrence Daly, a committed national official and a Labour Party member. Both particularly welcomed support from ambitious activists. Their endorsement, Brown knew, would help his chances of nomination as a Labour parliamentary candidate.

Another qualification for nomination was to have worked as a footsoldier for an existing candidate. Brown volunteered to help Robin Cook, a tutor at the Workers’ Education Offices Association and a leading member of Edinburgh council who was standing as the Labour candidate for Edinburgh Central. Their relationship, forged at the university, was built upon Cook’s acknowledged seniority. There was good reason for Brown to respect Cook, the son of a headmaster and grandson of a miner blacklisted for his activities during the General Strike of 1926. Cook, six years older than Brown, displayed forensic intelligence and remarkable debating skills. He had also secured Brown a teaching post at the WEA after Edinburgh University rejected his application.

Every night during the election campaign Brown recruited twenty friends, including his tenants, to knock on the doors of a working-class area in Edinburgh Central, a marginal constituency, urging support for the Labour candidate. On 28 February 1974, thanks to an unusually high swing, Cook won the seat with a small majority which many credited to Brown’s efforts. Yet, returning from the election night celebrations, Brown, Margarita and their friends expressed their surprise that Cook had not shown more gratitude for their hard work. Too often he had drunk whisky alone at one end of the Abbotsford’s bar while they drank beer at the other.

In the country as a whole Edward Heath won more votes than Labour, but not an overall majority of seats, and resigned. Few doubted that Harold Wilson, after forming a minority government, would call another election in the autumn. That was Brown’s opportunity. Edinburgh South, a marginal Conservative seat, was ideal territory. Securing the nomination required cut-throat tactics to elbow aside other applicants. ‘I was almost (#litres_trial_promo) a candidate,’ he said years later. ‘I was invited by people to stand, but it just didn’t work out. It would probably have been better had I done that.’ The impression is of a man facing a critical test of courage and bloody-mindedness who meekly withdrew. In reality, he faced a selection conference against the favoured candidate, Martin O’Neill, a friend from the student movement, and was beaten. In the election of October 1974 O’Neill lost the seat by 3,226 votes, leaving Brown ruefully to reflect that more aggressive campaigning might have tipped the balance.

Labour’s overall majority in the new parliament was three seats. Recognising that the government, with the Liberals’ help, could survive for some years, Brown reconciled himself to establishing his own life while he waited for the next opportunity. For the first months he suffered a personal crisis. He entered hospital for an operation on his right eye, uncertain whether he would emerge completely blind. Other than Margarita, few were aware of his true feelings. Some of those sharing his house say that he emerged from hospital crying, and unexpectedly began smoking twenty cigarettes a day. Some suspected that his hectic schedule of teaching at the WEA, researching his PhD, writing a book on James Maxton based on the politician’s private papers, and his Labour Party activities placed him under unusual pressure. Others accepted his explanation that his tears were for the Labour Party.

The party’s internal affairs had become ugly. North Sea oil had increased the demand for Scotland’s independence, and in the October election the Scottish Nationalists had won seven seats, campaigning on the slogan ‘It’s Scotland’s oil’. The shock of the SNP’s success, and the crisis in Scotland’s shipyards, coalmines and manufacturing industries, posed a threat in Labour’s heartlands. Labour’s Scottish leaders decided to end their dialogue with the Nationalists. In that battle, there would be no help from Harold Wilson and the party’s headquarters in London. Brown joined the campaign, attempting to discredit the Nationalists’ call for independence by compiling an account of socialist policies to rebuild Scotland.

The ‘Red Paper on Scotland’ was proposed by Brown as twenty individual essays bound in a slim 180-page volume. Among those invited to contribute were journalists including Tom Nairn, the playwright John McGrath, lecturer in politics John Foster, and two MPs, Jim Sillars and Robin Cook. After eighteen essays had been commissioned, Brown decided his idea was too good to waste. At parties, meetings and in pubs, he invited eighteen other contributions about Scotland’s economy and politics, devolution, the ownership of the country’s land and oil. ‘We’ll have to increase the price from £1.20 to £1.80,’ his flatmate John Forsythe, who was responsible for the publication through the Edinburgh University board, announced. ‘Or could we reduce the number of commissions?’ ‘No,’ replied Brown, ‘and it’s got to be £1.20.’

Unwilling to offend any contributors, he fled to the Meadow Bar to meet Owen Dudley Edwards, his genial tutor. ‘A great bubbly baby,’ was how Dudley Edwards described Brown. ‘One of the sweetest people I know, with a wonderful smile. He knows how to say “Thank you,” and his body language is reproachful if someone declines his request.’ ‘All right,’ Brown announced to Forsythe on his return from the pub. ‘£1.80, but no reduction in the contributions.’ The book’s print was reduced to the minuscule size of a Biblical dictionary’s footnotes, but it was still a success, heading the Scottish bestseller list for two weeks, although few readers can have ploughed through all the tiny script.

In microscopic print, Brown’s well-written introduction, ‘The Socialist Challenge’, criticised the puerile debate indulged in by the country’s politicians, who ignored ‘Scotland’s real problems – our economy and unacceptable level of unemployment, chronic inequalities of wealth and power and inadequate social services’. He offered a rigid solution to the contradiction of managing a capitalist economy while providing the requirements of society, rejecting ‘incentives and local entrepreneurship’, and supporting state planning to orchestrate a national economic revival. He advocated more nationalisation of Britain’s industry, a planned economy and the destruction of the ruling classes. Scottish socialists, he wrote, could not support independence, but should control more of their own lives. Because capitalism had failed, and the private ownership of industry was hindering ‘the further unfolding of the social forces of production’, Brown’s cure was neo-Marxism. Young Labour activists were now hailing Brown as a celebrity. His dramatic appearance and good oratory, enhanced by his immersion in the history and tradition of Scottish Labour, won admirers for his vision of ‘Ethical Socialism’. He could have been destroyed by his early success, but his upbringing reined in any temptation to boast. Privately, he nevertheless hoped that his achievement would ease the path to a nomination for a safe parliamentary seat.

Securing that nomination depended upon a successful apprenticeship. The party recognised Brown’s ability but wanted evidence of more than a commitment to the community and worship of the Bible, Burns and Keir Hardie. To prove his understanding of liberating working people, he was required to intone the religious code of the Scottish Labour movement – ‘socialism’ and ‘social justice’ – with suitable references to the fundamental morality established during the Scottish movement’s history. By 1976 he had established those ideological credentials, regurgitating endless facts to prove that Harold Wilson’s government and its technological revolution would create thousands of new businessmen and enterprises, revolutionising the nation’s wealth. As a party loyalist he qualified for nomination; but among many of Labour’s older generation his image grated. While the party faithful admired the impassioned man, some griped that he was too fast, too clever, and too interested in courting popularity. The picture of a disorganised twenty-three-year-old, wearing a dirty Burberry coat, carrying a plastic bag stuffed with newspaper clippings, pamphlets and notes, flitting between speeches and committee meetings, invariably late because he had forgotten his watch, hardly appealed to working-class stalwarts. They joked that while he held the plastic bag under his arm, the information seeped into Brown’s brain by osmosis through a sensor in his armpit.

Occasionally Brown returned to Marchmont Road close to tears. At political meetings he was shouted down by critics angry that he had acknowledged the SNP, a ghost the Labour Party preferred to ignore. The policies pursued by Harold Wilson’s Labour government antagonised many in Scotland, and Brown was among the casualties, blamed for deviation from true socialism. Some members of the Scottish Executive, especially Jimmy Allison, the party’s organiser, treated him roughly. In 1974 the party had opposed devolution, but subsequently, after receiving a report from the ‘Devolution Committee’ chaired by Brown, it supported partial home rule. The disagreements excited anger. ‘The older people (#litres_trial_promo) hated him,’ Henry Drucker, a writer and friend, recalled. John Forsythe listened to his long-haired friend’s lament that the representatives of the working class criticised him as soft, self-indulgent and a dilettante. Brown was frustrated that those he consulted for advice were not as clever as himself, and could not offer better insights into Labour’s problems in Scotland. His family life had not equipped him to deal with calculated ruthlessness. Any achievement would have to be the result of unglamorous hard graft.

Eventually his perseverance was rewarded. In 1976 he was nominated as the prospective candidate for Edinburgh South, a Conservative seat. Considering the growing antagonism towards the Labour government his election to the Commons was doubtful, but the breakthrough was critical. After a good speech in favour of devolution at the Scottish party’s conference in 1977 Brown was elected to Labour’s Scottish Executive. Full of excitement, he telephoned Donald Dewar, a solicitor and an MP since 1966 with whom he watched football matches, to share his excitement. The older politician instinctively replied, ‘I can assure you it will be awful.’ John Smith, the thirty-nine-year-old minister responsible for devolution in Westminster, was more supportive. Brown had been flattered to be invited to Smith’s home shortly after Smith’s appointment as a cabinet minister, and had been surprised to find that Smith was more interested in listening than in talking. Smith, Brown would appreciate, ‘genuinely believed people (#litres_trial_promo) were equal’. Like Donald Dewar, John Smith became another ‘friend and mentor’. Brown was content to have established himself close to the party’s possible future leaders.

His election to the party’s executive coincided with the earlier appointment of Helen Liddell, a bus driver’s daughter who would later be known as ‘Stalin’s Granny’, as the Scottish party’s general secretary, and George Robertson as chairman. His encounters with both did not improve his popularity. As BBC Scotland’s economics correspondent, Liddell had a high public profile, and was an attractive face for Labour. Her appointment did not interrupt her frequent appearances on television news. Self-promotion, carped her critics, seemed more important to Liddell than engaging in the grind of party work and leadership. Her supporters countered that her value was in forging good relations with people. That was no consolation for Brown. Generally he did not handle women well, and he particularly lacked affection for Liddell. At executive meetings he was humiliated as she launched criticisms of him, especially of the ‘Red Paper on Scotland’, whose neo-Marxism she regarded as a threat to the party, regularly beginning with the phrase ‘The national leadership says … ’ Those seemingly innocuous words could be fatal to Brown’s ambitions. His energy and politics were creating rivals and occasionally enemies, just as his need for friends and benevolent advisers had become greatest.

In 1978 his impatience to become an MP was damaging his relationship with Margarita. Repeatedly, planned visits to the cinema and parties were abandoned as he responded to a telephone call and rushed to yet another meeting. In desperation, one night she had telephoned Owen Dudley Edwards with a ruse, asking, ‘Can you come down? Gordon wants you.’ Dudley Edwards arrived to discover that Brown was still drinking in a pub with two friends. Leaving Margarita alone had caused him no concern. The three friends eventually returned, slightly merry. Normally Brown’s companions would crash out on the floor while he flopped in an armchair to read a serious book. But on this occasion, while Margarita loudly reproached him, he picked her up and laughingly carried her to their bedroom. ‘You can see how in love they are,’ sang Dudley Edwards.

In an attempt to restore their faltering relationship, Margarita organised a weekend trip to a country cottage, and disconnected the telephone. Brown exploded in a rage. Relationships with women were sideshows in his life. He had become disturbed by the uneasy contrast of living with a sophisticated woman who enjoyed good food and elegant clothes, and the plight of Scottish workers, striking in large numbers across the country. While the party was immersed in strife as it tried to resolve the turmoil, Margarita seemed merely to tolerate Scottish provincialism, being principally concerned about the arrangements to visit her family in Geneva and her royal friends in their palatial homes across Europe. After five years, she also wanted evidence that the relationship had a future. Regardless of his affection, Brown was uncertain whether he could commit himself to a woman who was not a socialist, or could risk appearing with a princess before a constituency committee.

This crossroads in his personal life coincided with a remarkable political opportunity. Alexander Wilson, the Labour MP for Hamilton, a town south of Glasgow, died, and the constituency was looking for a candidate for the by-election on 31 May 1978. Hamilton had many attractions for Brown. The seat was a Labour stronghold, several senior party members had offered him their support, and his parents had moved to a church in the town. The obstacles were the other aspiring candidates. Alf Young, a journalist, was among them, although his chance of success was nil. Brown telephoned Young and asked whether he would stand aside. Young politely refused, adding that George Robertson, the Scottish party’s former chairman, who was supported by a major trade union, appeared certain of success. Brown aggressively challenged Young’s obstinacy, but failed to persuade him to surrender. A decisive voice, Brown knew, would be Jimmy Allison’s, the party’s organiser and a mini-Godfather. ‘It’s tight,’ said Allison, who knew the area well, ‘but you can win if you fight.’ Crucially, Allison pledged his support if Brown mounted a challenge. There might be blood, warned Allison, but that was acceptable among brothers. Even George Robertson, the favourite, acknowledged that there would be ‘a big fight’ if Brown stood, and the outcome would be uncertain.

‘I don’t know,’ Brown told Allison a few days later. ‘I think I should be loyal to the people in Edinburgh South. I don’t want to be seen as a carpetbagger and offend the good people who have helped me.’ Allison dismissed that as an irrelevance. Brown grunted and agreed to contact the party activists in Hamilton. But they, Allison heard, were unimpressed by his eagerness to avoid a fight with Robertson. Brown spoke about not being disloyal to the electors of Edinburgh South, but in truth he lacked the courage to work the system with a killer instinct. His caution was unexpected. Six years earlier he had confidently challenged Michael Swann. Outsiders were puzzled why the same determination now seemed to be lacking. They failed to understand Brown’s insecurity. He was still shocked by the consequences of his university protest for his academic career. His judgement, he believed, had been faulty. While he could confidently repudiate intellectual arguments, he lacked the resilience to withstand emotional pressure. He needed reassurance, but he had no one he could rely on. Some of his friends would dispute that he lacked courage. Others would say he feared failure. His consolation was hard work. Diligence, he believed, merited reward, and without hard work there should be no reward. That credo may be commendable for normal life, but not for ambitious politicians. Brown withdrew. Without a serious challenger, Robertson was nominated, and won the by-election by a margin of more than 6,000 votes. If Brown had arrived in Westminster in 1978, his own life, and possibly the Labour Party’s, would have been markedly different.

Similar indecisiveness plagued Brown’s relationship with Margarita. For weeks he hardly spent any time in Marchmont Road. James Callaghan had succeeded Harold Wilson as Labour prime minister, and increasingly Brown was preoccupied by the erosion of Callaghan’s authority – the government’s dependence on other parties at Westminster for a parliamentary majority had become unreliable – and the slide towards industrial chaos. In Scotland the party’s problems were compounded by disagreement about devolution. A referendum was to be held in March 1979, and the party was divided.

Excluded from those preoccupations, Margarita decided to end the relationship and leave Marchmont Road. ‘I never stopped (#litres_trial_promo) loving him,’ she said in 1992, ‘but one day it didn’t seem right any more. It was politics, politics, politics, and I needed nurturing.’ Brown’s friends would say that he terminated the relationship. ‘She took it badly,’ they said, ‘that she was less important than meetings.’ But in truth Margarita simply was fed up, and walked out. A few weeks later she met Jim Keddie, a handsome fireman, with whom she started an affair that would last for six years. During the first months Brown telephoned her frequently to arrange meetings, but despite his entreaties that she return, she refused. Over a long session of drinks with Owen Dudley Edwards, Brown repeatedly said, ‘It’s the greatest mistake of my life. I should have married Margarita.’ If he had been elected to Westminster in 1974 or 1978 they might have married, but the uncertainty created irreconcilable pressures. Jim Keddie was convinced that Brown remained haunted by Margarita. Although Margarita never mentioned any regret about leaving Brown, for several months after her departure she would turn up without Keddie at parties in Marchmont Road, or would see Brown at dinner parties held by Wilf Stevenson, a man convinced of his own glorious destiny. Keddie sensed that she hoped the relationship might be rekindled, but there was no reunion. ‘It just hasn’t happened,’ Brown would say thereafter about love and marriage. In the space of a few months he had lost the chance of both an early arrival in Westminster and marriage to a woman he loved. Whether he was influenced by his research into James Maxton’s life, with all its failures and disappointments, to avoid similar distress himself is possible, but he had failed to overcome his caution and indecisiveness.

Beyond a tight circle of friends, Brown concealed his emotions and re-immersed himself in politics. For an aspiring realist, the prognosis could not have been worse. The trade unions were organising constant strikes, public services were disintegrating and inflation was soaring. The ‘winter of discontent’ began. Rubbish lay uncollected on the streets, the dead remained unburied and hospital porters refused to push the sick into operating theatres. The middle classes and many working-class Labour voters switched to the Conservatives to save them from what they felt had become a socialist hell. The opinion polls predicted Margaret Thatcher’s victory whenever James Callaghan dared to call the election. Brown’s prospects in Edinburgh South looked dismal, but once again he was offered an attractive alternative.

Martin O’Neill, who would himself be elected to parliament in 1979, called Brown with an offer. O’Neill was chairman of the Labour Party in Leith, and he explained, ‘There isn’t a strong candidate here, and you could win a safe seat.’ Brown hesitated. ‘I don’t know,’ he replied. ‘I don’t think I can let the people in Edinburgh down.’ He expressed his fear of bad publicity after his failure to stand in Hamilton, and the probability of being tarred as an opportunist. The impression again was of indecision and fear of a competition whose outcome was, despite O’Neill’s assurances, uncertain. He sought refuge in hard work.

The first battle was to persuade the Scottish people to support devolution in the forthcoming referendum. Without uttering any overtly nationalist sentiments, he campaigned in favour of the ‘yes’ vote, speaking at dozens of meetings. Despite campaigning in the midst of widespread strikes, Brown believed he could deliver victory. Scotland, he argued, did not share England’s disenchantment with the Callaghan government. Fighting against the odds brought the best out of him. During one debate against Tam Dalyell in York Place, Edinburgh, Brown arrived after a last-minute invitation. ‘He stood up to me better than anyone else,’ Dalyell told a friend afterwards. ‘I was pretty formidable, but he had thought about it better than anyone I had met.’ Among his other opponents was Robin Cook, praised by some but damned by more, especially the former Labour MP Jim Sillars, who would later join the SNP: ‘Cook believed that he was intellectually superior to God.’ Dalyell watched the two sparring with each other. ‘They were two strong young men who knew that one of them would get in the way.’

On election day, 1 March 1979, Scotland’s airports were closed and there were food shortages. Productivity had fallen since 1974, annual wage increases were about 15 per cent and inflation was 15.5 per cent. The ‘yes’ and ‘no’ votes were evenly divided, but under the rules of the referendum the ‘yes’ vote could only be successful if it received not just a simple majority, but a majority of all those who were entitled to vote. Brown, like many in his party, deluded himself about the reasons for failure. Scotland’s new oil wealth had encouraged the belief that while England was dying, their country was being revitalised. Scottish voters, Brown failed to understand, were disenchanted by Labour. He was nevertheless optimistic about victory in the general election, which was finally called for May 1979.