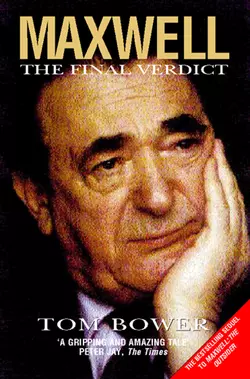

Maxwell: The Final Verdict

Tom Bower

The Book the Brothers tried to stop. Now available in ebook format.Robert Maxwell was one of the most flamboyant, complex and - seemingly - the richest self-made men in post-war Britain. The tentacles of his power stretched from newspapers to football, from the boardrooms of his many companies and into the thoughts of the world at large.Maxwell: The Final Verdict is a story of greed and corruption on a truly mammoth scale. Revealing, for the first time, how Maxwell hurtled tumultuously towards disaster, it draws upon an exceptional resource of inside knowledge, such as could only have been assembled by the leading investigative journalist of his generation. Including intimate accounts of Maxwell’s lifestyle and personality from his closest associates - from world politicians to girlfriends - answering all the questions surrounding his death and the investigations which followed it, and with full details of the trial of Kevin and Ian Maxwell, this is the most explosive expose of the decade.

Tom Bower

MAXWELL

THE FINAL VERDICT

Copyright (#u9e0e101f-2075-5204-9707-fa0bbf4541f0)

William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd. 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk/)

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers 1996

Copyright © Tom Bower 1995

Tom Bower asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins ebooks

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication

Source ISBN: 9780007292875

Ebook Edition © JUNE 2012 ISBN 9780007394999

Version: 2016-11-09

Dedication (#u9e0e101f-2075-5204-9707-fa0bbf4541f0)

To Sophie

Epigraph (#u9e0e101f-2075-5204-9707-fa0bbf4541f0)

You are my teacher and all my life you have tried to demonstrate the principles underlying every action or inaction … Above all, you have given me the sense of excitement of having dozens of balls in the air and the thrill of seeing some of them land right.

KEVIN MAXWELL, written to his father in 1988

The Maxwell Foundation will be one of the richest of its kind in the world.

JOE HAINES, 1988

Contents

Cover (#u9cf32b3b-e4bc-52d0-a68b-b51363ad5e62)

Title Page (#uda13b901-7499-5fcf-866a-c016f122d270)

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

Preface

1 The Autopsy – 9 November 1991

2 The Secret – 5 November 1990

3 Hunting for Cash – 19 November 1990

4 Misery – December 1990

5 Fantasies – January 1991

6 Vanity – March 1991

7 Flotation – April 1991

8 A Suicide Pill – May 1991

9 Two Honeymoons – June 1991

10 Buying Silence – July 1991

11 Showdown – August 1991

12 ‘Borrowing from Peter to Pay Paul’ – September 1991

13 Whirlwind – October 1991

14 Death – 2 November 1991

15 Deception – 6 November 1991

16 Meltdown – 21 November 1991

17 The Trial – 30 May 1995

Epilogue

Keep Reading (#litres_trial_promo)

Notes

Company Plan

Dramatis Personae

Glossary of Abbreviations

Index

Acknowledgements

About the Author

By the Same Author

About the Publisher

Preface (#u9e0e101f-2075-5204-9707-fa0bbf4541f0)

On 12 May 1989, Peter Jay signed a short letter marked ‘Private and Confidential’ addressed to George Potter OBE, a director of Control Risks, one of Britain’s leading private detective agencies. Jay, the chief of staff to Robert Maxwell, thanked Potter, a former police officer, for ‘your letter and for the time you gave to meeting me and preparing it’.

Potter’s letter had described his surveillance of ‘the location and the levels of background radiation in the area’. Potter was referring in cryptic fashion to a surreptitious reconnaissance mission which he had undertaken around my home in Hampstead, north-west London. He continued: ‘Extremely sophisticated equipment does exist which might overcome the technical problems. Its acquisition would cost an estimated £50,000.’ The private detective was describing a scanner which would emit rays capable of penetrating my home and ‘reading’ the contents of my computer’s hard disc.

Wisely, Potter cautioned Jay about the problems. First, the detective wanted to be paid in advance the £50,000 for the equipment and also some fees. Secondly, Potter warned, he had ‘reservations as to the possibility of obtaining the evidence you require and the ability to keep the operation covert’. The detective’s concerns were understandable. A van carrying the scanner would be parked at the bottom of my garden in a narrow service road used by the Hampstead postal sorting office. Remaining unobtrusive for long periods would be difficult.

Jay, who had once basked in the glorious description as one of Britain’s ‘cleverest men’, was not slow to grasp Potter’s cautionary tone but was sensitive to the dissatisfaction that this report would cause his demanding employer. Little had been achieved since, one month earlier, he had received a briefing from Tony Frost, an assistant editor of the Daily Mirror, following his investigation around my Hampstead home.

Frost had accurately noted my address and identified my car, before reporting that ‘neighbours say his working hours are “rather erratic” with frequent trips away’ and that I ‘spent “a full working week” at the offices or studios of the various TV companies who commission his work’. Curiously, he noted that my newsagent ‘seemed to know Bower quite well’. After alluding to my financial status, Frost observed that my road is ‘typical of the more up-market parts of Hampstead’ and flatteringly noted, ‘the house looked to be tastefully and expensively decorated inside’.

Copies of Frost’s memorandum were also sent to Eve Pollard (then editor of the Sunday Mirror), Ernest Burrington, (then editor of the People) and Joe Haines (then a Daily Mirror columnist and a director of the Mirror Group) – all owned by Maxwell’s Mirror Group Newspapers.

Jay filed Frost’s report in his bulging ‘Bower File’, which was marked in large letters ‘Private and Confidential’, reflecting the heading of every document it contained. Each letter on the topic signed by the chief of staff urged its recipient to treat the matter with utmost secrecy. Jay had become rather proficient in conducting the operation.

Ever since his employer had heard in summer 1987 that I was planning to write Maxwell: the Outsider, an unauthorised biography of himself, Peter Jay had been employed as his chief of intelligence to gather and co-ordinate information about my activities and identify those people whom I was interviewing. On one occasion, detectives had clearly followed me to a meeting with Anne Dove, Maxwell’s former secretary, with whom he had enjoyed a close relationship in the 1950s. The results of their work were formalised under Jay’s supervision in sworn statements which would be used to back the avalanche of writs and court hearings, costing £1 million, which obsessed Maxwell until his death.

Initially, Maxwell tried to prevent the book’s publication in February 1988, at the same time publishing his own version written by Joe Haines. When my book hit the top of the bestseller list, Maxwell sought through individual cajolery and writs to prevent every bookshop in Britain selling the title. Eventually he was successful in this endeavour, but he nevertheless continued to hound me and the publishers by pursuing various writs for libel. Jay’s task was to co-ordinate and supervise the unprecedented legal battle.

By spring 1989, one year after publication, when the first of three publishers had agreed to publish the paperback version only to retreat rather than face the subject’s wrath, Maxwell’s anger was increasing in parallel to the secretly developing insolvency of his empire. His fury had shifted from the book’s accurate description of his unaltered dishonesty to something which in his view was more sinister. He believed that I had become a focus for his enemies and a receptacle of damaging information. Just as he was finalising a deceptive annual financial report for the Maxwell Communication Corporation, of which he was chairman, he embarked upon a new venture to humiliate the book’s publisher and bankrupt its author.

Four lawyers were Maxwell’s principal advisers. Lord Mishcon and Anthony Julius were his solicitors and Richard Rampton QC and Victoria Sharp were the barristers. During their frequent court appearances, they betrayed no hint of doubt about their client’s virtues. On the contrary, they pursued his mission with depressing vigour, commitment and pitilessness.

Their client’s anger had by then increased still further. The book had been published in France and his defamation action there had failed. To his fury, a court had ordered that he pay me FFrs 10,000 in costs. The threat that the book might also be published in his beloved New York galvanised him to resort to more draconian measures.

Maxwell had become convinced, in the words of Stephen Nathan, another barrister hired for advice, that I had ‘compiled (and continued to compile) an extensive record of information concerning Mr Maxwell and has put the distillation of that information on to a computer which he keeps at home’. Maxwell’s source was Frost, who, during his gumshoe expedition around Hampstead, had picked up from an ‘unidentified source’ the notion that my study had become a centre for subversive activities against the Chairman.

Nathan had been asked to advise whether I could be prosecuted for failing to register as a data-user under the Data Protection Act 1984 or, better still, whether Maxwell might approach the Director of Public Prosecutions. The DPP, the Chairman hoped, would direct the police to seize the computer without warning. That course, advised Nathan, would be possible only if Maxwell could persuade the DPP of the allegedly dangerous contents of the computer.

Frustrated by Nathan’s wishy-washy advice, Maxwell ordered Lord Mishcon to seek the seizure of my computer on the orders of a judge under an Anton Piller order. Naturally Jay passed on the instruction to Julius. Such an order, suggested Jay, would enable ‘Bower’s computer records to be seized under warrant, without advance notice being given, therefore without Bower having an opportunity to destroy or conceal such records’. In retrospect, the irony of Maxwell mentioning Anton Piller was manifest. The order, as Mishcon explained, is used to obtain the seizure of documents for the investigation of fraud or systematic dishonesty. And Jay, in passing on Mishcon’s advice to the Chairman in another ‘Intermemo’ on 7 April 1989 headed ‘Bower’s Computer’ and marked ‘Strictly Confidential’, noted mournfully, ‘Legally speaking, this is not (quite) the situation with Bower.’

Mishcon urged his client to adopt the customary course and apply to the court for the computer records. But, he cautioned, ‘Our evidence that these records exist is thin.’ Therefore, advised the peer, ‘I recommend that investigations should continue.’ Hence Maxwell ordered Jay to seek the evidence required, and this was why Jay was inspired to ask the detective to place the scanner at the bottom of my garden. But after receiving Potter’s disappointing news, Jay concluded, ‘It is not really practical to proceed along the lines we discussed.’

That was by no means the end of the battle. Until October 1991, Maxwell regularly held meetings with lawyers and with his personal security staff to propel the battle towards my bankruptcy and his vindication. The readiness of Peter Jay, a journalist and former British ambassador, to function as his willing tool was sadly not unique in Britain or elsewhere. He merely epitomised a cravenness common among a horde of self-important personalities and powerbrokers whose self-esteem was boosted by the Chairman’s attentions and deep purse.

Unfortunately, the sort of campaign directed against my book acted as a disincentive for most newspapers against exposing Maxwell in his lifetime. Many blame Britain’s libel laws and lawyers’ fees for protecting him, yet the law and its expense were not the sole reason for British newspapers’ reluctance or inability to uncover his crimes. More important was the environment in which newspapers now operate.

Few newspaper editors and even fewer proprietors nowadays relish causing discomfort to miscreant powerbrokers. By nature anti-Establishment, the so-called ‘investigative’ reporter finds himself working for newspapers which are increasingly pro-Establishment. Only on celluloid, it seems, does an editor smile when listening to a screaming complainant exposed by his journalists.

Proper journalism, as opposed to straightforward reporting or the columnists’ self-righteous sermonising, is an expensive, frustrating and lonely chore. Often it is unproductive. Even the rarity of success earns the ‘investigative’ journalist only the irksome epitaph of being ‘obsessional’ or ‘dangerous’. The final product is often complicated to read, unentertaining and inconclusive. No major City slicker has ever been brought down merely by newspaper articles. Like the Fraud Squad, financial journalists usually need a crash before they can detect and report upon the real defects. Often, only with hindsight does the crime seem obvious. Even though in Maxwell’s case his propensity to commit a fraud had been obvious since 1954, it was almost impossible for any journalist to produce the evidence contemporaneously.

Moreover, many of those who reported Maxwell’s affairs during the 1980s were only vaguely aware of the details of the Pergamon saga in 1969, when his publishing empire had disintegrated amid suspicions of dishonesty which appeared to have terminated his business life. After three damning DTI reports, no one expected Maxwell’s resurrection. However, the DTI inspectors, having found the evidence of fraud and voiced a memorable phrase about his unfitness to manage a public company, had not directly accused him of criminality. It was the inspectors’ cowardly reluctance to publish their real convictions and the police failure to prosecute which permitted Maxwell during the 1980s, when explaining his life, to distort the record of the Pergamon saga.

Accordingly, by 1987, Buckingham Palace, the City, Westminster and Whitehall had forgotten or forgiven the past. In the year in which Maxwell’s final frauds began, most journalists reflected the prevailing sentiment and were willing to afford him the benefit of the doubt.

To have broken through Maxwell’s barrier required not only a brave inside source who was willing to steal documents but also someone who would risk the Chairman’s inevitable writ. But, unlike in America, whistleblowers are castigated in Britain, where secrecy is a virtue. To break those barriers also required expertise and a lot of money, increasingly unavailable to newspapers and to television. So almost until his end Maxwell enjoyed a relatively favourable press, although journalists were not to blame for the canker’s survival.

The real fault for Maxwell’s undiscovered fraud belongs to the policemen employed in the Serious Fraud Office, to the civil servants, especially in IMRO and the DTI, who are empowered to supervise Britain’s trusts and corporations, and to the accountants at Coopers and Lybrand who were his companies’ auditors. As with most of Britain’s financial scandals, those arrogant, idle and ignorant bureaucrats, having failed in their duties, were not embarrassed nor dismissed, because they were protected by self-imposed anonymity. It was their good fortune that many blamed Britain’s libel laws for the failure to expose Maxwell’s fraud. But that was and remains too easy. Maxwell prospered because hundreds of otherwise intelligent people wilfully suspended any moral judgment and succumbed to their avarice and self-interest. To suggest that much will be learned from Maxwell’s story is to ignore past experience, but his story is an extraordinary fable, not least because only now can one read the final verdict.

ONE The Autopsy – 9 November 1991 (#u9e0e101f-2075-5204-9707-fa0bbf4541f0)

The corpse was instantly recognizable. The eye could follow the jet-black hair and bushy eyebrows on the broad Slav head down the huge white torso towards the fat legs. Until four days earlier, the puffy face, recorded thousands of times on celluloid across the world, had been off-white. Now it was an unpleasant dark grey. The body was also disfigured. An incision, 78 cm long, stretched from the neck down the stomach to the crotch. Another incision crossed under the head, from the left shoulder along the collar bone. Firm, black needlework neatly joined the skin to conceal the damage to the deceased’s organs.

Lying on a spotless white sheet in a tiled autopsy room, the corpse was surrounded by eight men and one woman dressed in green smocks. An unusual air of expectancy, even urgency, passed among the living as they stood beneath the fierce light. It was 10.25 on a Saturday night and there was pressure on them to complete their work long before daybreak. Over the past years, thousands of corpses – the victims of the Arab uprising – had passed through that undistinguished stucco building in Tel Aviv. But, for the most part, they had been the remains of anonymous young men killed by bullets, mutilated by bombs or occasionally suffocated by torture.

This cadaver was different. In life, the man had been famous, and in death there was a mystery. Plucked from the Atlantic Ocean off the Canary Islands, he had been flown for burial in Israel. Standing near the corpse for this second autopsy was Dr Iain West, the head of the Department of Forensic Medicine at Guy’s Hospital, London. His hands, encased in rubber gloves, were gently touching the face: ‘He’s been thumped here. That looks genuine. You don’t get that falling just over the edge of a boat. You don’t get this sort of injury.’ West’s Scottish-accented voice sounded aggressive. Retained by the British insurance companies who would have to pay out £21 million if the cause of death were proved to have been accident or murder, he found his adrenalin aroused by a preliminary autopsy report signed two days earlier by Spanish pathologists. After twenty-one years of experience – and 25,000 autopsies – he had concluded that there were no more than two Spanish pathologists who deserved any respect: the remainder were ‘not very good’. The conclusion of Dr Carlos Lopez de Lamela, one of that remainder, that the cause of death was ‘heart failure’ was trite and inconsequential. West was thirsting to find the real cause of death. His first suspicion was murder. Yet he knew that so much of pathology relied upon possibilities or probabilities and not upon certainties. Mysteries often remained unresolved, especially when the evidence was contaminated by incompetence.

The Briton’s position at the autopsy was unusual. Under the insurance companies’ agreement with the Israeli government, he could observe but not actively participate. West regretted that he would not be allowed to follow the contours and patterns of any injuries which might be discovered and privately felt slightly disdainful of his temporary colleague, Dr Yehuda Hiss. He recalled the forty-five-year-old Israeli pathologist – then his junior – learning his craft in Britain in the mid-1980s. He had judged him to be ‘competent’, although unused to the traditional challenges of autopsy reports in Britain. West was nevertheless now gratified to learn that his lack of confidence in the Spaniards was partially shared by Hiss. In the Israeli’s opinion, Dr Lamela’s equivocation about the cause of death was unimpressive.

West watched Hiss dictate his visual observations. Touching the body gently, even sensitively, the Israeli noted small abrasions around the nostrils and rubbed skin under the nose and on the ear, but no signs of fresh epidermal damage anywhere on the head or neck. There were no recently broken bones. Although the body had apparently floated in the sea for up to twelve hours, the skin showed no signs of wrinkling or sunburn. ‘We’ll X-ray the hands and the foot,’ ordered Hiss.

His dictation was interrupted by West: ‘I wonder if they’ve looked at his back?’

‘No, no,’ replied Hiss, going on to note a small scar, thin pubic hair and circumcision.

Again he was interrupted: ‘The teeth are in bad condition.’

‘The dental treatment is poor,’ agreed another Israeli.

‘Very poor’, grunted West, ‘for a man who was so rich.’

‘Are you sure it’s him?’ asked an Israeli. ‘We’d better X-ray the teeth for a dental check.’

‘Well, it looks like him,’ snapped West. ‘The trouble is we’re up against time. He’s being buried tomorrow. I think we’ll take fingerprints.’ Again, he criticized the Spaniards: ‘The fingernails haven’t been cut off. They said they’d done it.’

Midnight passed. It was now the day of the burial. The corpse was turned over. ‘We’ll cut through and wrap it back,’ said West impatiently. The two pathologists had already concurred that the Spanish failure to examine the deceased’s back was a grave omission – it had been a common practice in Britain since the 1930s, as a method of discovering hidden wounds.

There was no sentiment as two scalpels, Hiss’s and an assistant’s, were poised over the vast human mound. None of the doctors contemplated its past: the small baby in the impoverished Czech shtetl or ghetto whose soft back had been rubbed after feeding; or the young man whose muscular back had been hugged by admiring women; or the tycoon whose back five days earlier had been bathed in sunshine on board a luxury yacht worth £23 million. Their scalpels were indiscriminate about emotions. They thought only of the still secret cause of death.

After the scalpels had pierced the skin and sliced through thick, yellow fat on the right side, West’s evident anticipation was initially disappointed: ‘I’m surprised that we didn’t find anything.’ A pattern of bruises was revealed to be only on the surface, the result of slight pressure, but not relevant to the cause of death. More dissections followed, mutilating the body tissue, slitting the fat, carving the flesh inch by inch in the search for the unusual. Minutes later there was a yelp.

‘Do you see that?’ exclaimed Hiss.

‘It’s a massive haematoma!’ gasped West, peering at the discovery. There, nestling among the flesh and muscle in the left shoulder was a large, dark-red blob of congealed blood.

‘Nine and a half by six centimetres,’ dictated Hiss in Hebrew, ‘and about one centimetre thick.’

West prodded the haematoma: ‘There’s a lot of torn muscles – pulled.’ It was those tears which had caused the bleeding.

Here was precisely the critical clue missed by the Spaniards: since there were no suspicious bruises on the skin, they had lazily resisted any probing. Now the new doctors were gazing at violently torn fibres. Yet Hiss was not rushing to the conclusion he sensed was already being favoured by West. ‘The trouble is, it’s also an area where you often hit yourself,’ he observed.

‘It’s not a hit,’ growled West.

There was, they agreed, no pattern of injuries of the kind which usually accompanies murder – no tell-tale grip, kick or punch marks, no small lacerations on the skin which at his age would easily have been inflicted in the course of a struggle or by dragging a heavy, comatose body.

‘There’s tearing,’ insisted West, peering into the corpse. ‘Violent along the muscle.’ The dissecting continued. Another muscle tear was found near the base of the spine and a third haematoma deep in the muscle in the front abdomen. The blood was so localized, they concluded, that the tears must have occurred shortly before death.

By 12.30, as the cadaver steadily ceased to resemble a human being, West became quite certain: ‘The muscle fibres were torn in a desperate attempt to grab something.’ Hiss did not reply. As the legs and each finger were cut open to scour for other secrets, he remained reserved. The embalmer’s formalin, he realized, had destroyed any chance of finding conclusive evidence. ‘It’s well worth doing, isn’t it?’ repeated West as they drank coffee.

‘Yes,’ replied Hiss, still looking for a pattern of injuries and still feeling restrained by a Health Ministry official’s edict that he should be cautious (the edict was possibly a consequence of the friendship between the deceased and the serving minister of health).

The corpse was turned over on to its shredded back. The Spanish stitches were cut by a sharp scalpel. It was just past one o’clock in the morning and the pathologists were about to enter already trodden ground. Swimming in formalin within the distastefully brown chest cavity were the remains of the Spaniards’ handiwork.

Dr Lamela, the senior Spanish pathologist, had carried out his duties in circumstances very different from those enjoyed by the Israelis. Working in a cramped, ill-lit autopsy room, he had lacked important instruments, and had afterwards been denied any laboratory in which to conduct essential scientific tests. Aged thirty-five, he was a reluctant pathologist, obtaining little satisfaction from his task. In his three-and-a-half-hour investigation of the virgin corpse, he had noted that there were no external marks, bruises or perforations of the skin, the obvious signs of murder or violent death. Later tests had confirmed that no poisons were present.

Lamela’s next theory was drowning. But he had noticed no water in the respiratory tracts leading to the lung, which ruled out death by drowning. Nor had he found much water inside the lung tissue. The single, reliable test for judging whether the deceased was alive or dead when he fell into the sea had been frustrated by nature. That proof depended upon traces of the sea’s diatoms (microscopic algae) in the bone marrow. If the person had fallen living into the sea and swallowed water, the diatoms would have entered the bone marrow, providing irrefutable evidence of drowning. Subsequent tests revealed that at the point in the Atlantic where the corpse had been discovered and hoisted into a helicopter, the seawater contained no diatoms. The ‘little’ water in the lungs Lamela ascribed to pulmonary oedema, water which could arise through a heart attack. He therefore relied upon speculation rather than scientific proof when, mistakenly believing that the deceased was a strong swimmer, he excluded drowning and suicide as a cause of death.

Instead, Dr Lamela had concentrated upon the coronary arteries to the enlarged heart. Both were 70 per cent constricted. The evidence of a heart attack seemed strong. The twenty-two-stone man had lived with only one functioning lung and a diseased heart, and the right ventricular muscle of the stricken heart was acutely enlarged. His widow had disclosed a medical report written some years earlier which had noted a lack of oxygen in the blood, a common cause of sudden death. Taking into account the deceased’s complaints to the ship’s crew just before his death about the temperature in his cabin, Lamela concluded that the fatality had been caused by a heart attack. But, by scientific criteria, he was again speculating. He had failed to test whether there was an infarction of the heart muscle (a noticeable scar in the heart tissue), a certain indicator of an attack. Instead he had relied upon the small blemishes which revealed slight attacks in the past. His shortcomings were manifest.

At 1.20 on Sunday morning in Tel Aviv, eight men and one woman peered into the evidential debris bequeathed by Lamela, the stench from the formalin irritating their eyes and noses. As an assistant ladled the liquid out of the cadaver, Hiss complained, ‘There are some bits here you don’t recognize as a human being’s.’ The Spaniards had butchered the evidence. Dissected organs had been thrown into the corpse rather than sealed in a plastic bag. What remained of the lungs was full of water, but whether natural fluids, seawater or formalin was impossible to determine. The dissection of a remnant of the lung revealed some froth. ‘Consistent with both heart attack and drowning,’ the pathologists agreed. Examination of the liver revealed acute sclerosis, consistent with alcoholism. What remained of the other organs was practically worthless.

‘There’s no heart, nothing,’ complained West.

‘I think we should send the bill for this one to the Spanish,’ laughed West.

‘To the King, Juan Carlos,’ agreed the Israeli.

Suddenly, another assistant excitedly announced the discovery of a blood clot in the head. Further examination revealed no bruising. It was just accumulated blood fixed with formalin, West and Hiss agreed, a relic of Lamela’s butchery. A deep bruise near the right ear also contributed nothing to establishing the cause of death but was probably contemporaneous with the tearing of the muscles. The British pathologist’s earlier excited conclusion that ‘He’s been thumped’ had been jettisoned, along with his initial assumption of murder.

At 2.30 a.m., their work was completed. ‘I think it’s been a very bloody dissection,’ mourned West as he lit a cigarette. Stepping into the warm air outside, he walked towards his car. He would drive back to Jerusalem, where he had landed just twelve hours earlier on a Gulfstream jet formerly owned by the man whose corpse he had just abandoned. ‘I’ll look at Jerusalem before I go home,’ he decided as he sat back in the car for the fifty-minute journey to the Holy City.

The body would soon be transferred to the same destination for its funeral after a mortician had performed some rapid repairs. It would be buried with a mystery. Three pathologists – British, Spanish and Israeli – had ruled out murder but disagreed on the cause of death. Both Hiss and West discounted Lamela’s dismissal of drowning. The ambivalent evidence prevented any definite decision. But Hiss supported the Spaniard’s theory of a heart attack.

In the Israeli’s scenario, the deceased had suffered the preliminaries of the attack, left his cabin and walked to the rail overlooking the sea. Either stumbling or in the early stages of the attack, he had fallen forward, toppling over the ship’s rail or under a steel cord in the stern. At the last moment, he had grabbed at the rail, torn his muscles and, in pain, had plunged into the dark wilderness where the heart attack had come to a swift conclusion. ‘I think he drowned with an epidural haematoma,’ said Hiss.

Suicide was ruled out by the Israeli. In those circumstances, he argued, suicides never cause themselves violent harm before their death. Nor do those contemplating suicide jump naked to their death, and the deceased’s body had been found without the nightshirt which he had worn that night.

On reflection, West was dismissive of Lamela and Hiss. The Briton’s conclusions were determined by the torn muscles and coagulated blood. Lamela would say in retrospect that the muscles had torn during the convulsions of the heart attack. Both West and Hiss rejected that as ‘ridiculous’. Both agreed that the muscles had been ripped by a sudden jerk after the deceased’s left hand had grabbed something. The pain in those seconds would have been intense. West discounted a heart attack, although ‘he had a heart disease which was potentially lethal’. He had two reasons: first, because ‘I would expect him to have fallen on to the deck’; second, even if he had toppled over the railing, ‘He would have been acutely breathless, convulsing and unable to grab anything.’

West favoured the theory that the muscle tears were caused in the deceased’s passage towards suicide or by an intervening accident. He had left his cabin and walked to the railing of his yacht. After climbing over, he had held on pondering his fate. Either he had accidentally slipped or he had deliberately jumped. In either event, in a sudden reaction, he had grabbed for the rail to save himself. His twenty-two stone combined with the fall’s momentum had ripped his muscles and within seconds forced him to release his grip. He had fallen into the dark sea where he had drowned. But even that was supposition: ‘I think that probably death was due to drowning. I can’t prove it. Nor can I prove the opposite.’ In an English court, ‘The verdict would be an open verdict.’

Distillation of the pathologists’ opinions leads towards the most reliable conclusion. Feeling unwell, the deceased had been on deck for fresh air. Stumbling, probably from a minor heart attack, he had fallen forward, passing under the steel cord or over the rail and, as he had twisted to grab it, had hit the side of his head against the boat. In double agony, he had lost his grip and dropped into the sea. There he died, some time later, from exhaustion or a heart attack.

But two critical issues remained unresolved. First, the cabin door had apparently been locked from the outside. If true, it pointed either to suicide or to murder, because anyone feeling unwell would be unlikely to lock a door. Secondly, the corpse had been found in seas notorious for strong currents. Twelve hours had elapsed between the deceased’s disappearance and his discovery. In the frequent occurrences of drowning around the Canary Islands, bodies are rarely found if missing for more than nine hours. Dr Lamela, with years of experience of drownings in that area, was puzzled by the condition of this particular corpse, which had allegedly spent twelve hours in the sea. ‘The body’, he recorded, ‘appeared to have been dead longer than it was in the water.’

Lamela’s conjecture spawned tales of intrigue, unidentified frogmen, a mystery ship, satellite photographs, radio intercepts, intelligence-service rivalries, unauthorized weapons deals, stolen gold, secret bank accounts, money laundering, untraceable poisons and ultimately murder. Given the identity of the corpse, nothing was unimaginable. At four o’clock in the morning of 10 November 1991, it was en route to Jerusalem to be fêted by the world’s most enigmatic government as a national hero.

In his lifetime, the deceased had boasted of his final bequest. ‘Billions of pounds’, he had crowed, ‘will be left to charity. My children will inherit nothing.’ The reality, he knew, was very different. He had bequeathed a cataclysm, but the full nature of his criminality was still known only to his youngest son.

TWO The Secret – 5 November 1990 (#u9e0e101f-2075-5204-9707-fa0bbf4541f0)

The plan was finalized precisely one year before he mysteriously died.

Concorde landed at New York’s JFK airport six minutes late on 5 November 1990. Among the forty-nine passengers gliding self-assuredly off the supersonic flight from London at 9.26 a.m. was Ghislaine Maxwell, the twenty-eight-year-old daughter of the media billionaire. Elegantly dressed and wearing a distinctive hat, Ghislaine was blessed as Robert Maxwell’s youngest and favourite child. But even to her father’s most loyal employees, the thin, would-be socialite was condemned as arrogant and a beneficiary of her father’s fame and power. ‘She’d ask for a cigarette and walk out with the packet,’ complained Carol Bragoli, a secretary.

That morning she seemed more purposeful than usual. Robert Maxwell had entrusted her with a mission to carry an envelope across the Atlantic. Stepping into a chauffeured limousine, she was whisked to 200 Park Avenue in Manhattan. Awaiting her on the twenty-eighth floor was Ellis Freedman, an elderly lawyer who worshipped her father and had served his interests for nearly forty years. Ushered into the waiting room, the messenger handed over the envelope. There was no reason for the young woman to be suspicious. Yet, unknowingly, she had become enmeshed in a plan, initiated by her father, to steal $200 million.

Eleven days earlier, at 8 a.m. on 25 October, Kevin Maxwell, the thirty-one-year-old joint managing director of the Maxwell empire, had met Albert Fuller, the thirty-nine-year-old accountant responsible for the empire’s treasury. Like all of Maxwell’s most trusted employees, Fuller’s qualification for his well-paid position was his tolerance of abuse dispensed around the clock by the tycoon. Deliberately, even cynically, Maxwell had gathered in his inner sanctum apparatchiks who were not only beholden to him but even adulated him. Although technically competent, they were weak men attracted to a father-figure. Fuller was especially grateful to Maxwell. Two years earlier, he had been involved in the loss of a banker’s draft worth £4.7 million but had been exonerated and allowed to resume work after several weeks’ suspension.

Fuller did not query Kevin’s instruction to fly immediately to New York. His tasks seemed simple. From one office he was to retrieve a share certificate numbered B1001, bearing 10.6 million shares in Berlitz, the famous international language school. Then he was to travel to another office and there exchange the single document, worth over $200 million, for nine certificates of varying denominations. There was little cause for Fuller to be suspicious about that effortless transaction. Kevin’s request was not illegal and his need for discretion was understandable. Berlitz was owned (with 56 per cent of the shares) by the American Macmillan publishing company, which in turn was owned by Maxwell Communication Corporation (MCC) – the public company, still 60 per cent owned by the founder himself, which aspired to dominate the world’s exploding media industry. By 30 October, Fuller had returned to London, his mission accomplished.

Six days later, an hour before Ghislaine’s arrival in New York, Robert Maxwell telephoned Ellis Freedman, his lawyer. The instructions again seemed straightforward. Ghislaine, said Maxwell, would be bringing an envelope with nine share certificates showing Macmillan’s ownership of the Berlitz shares. Freedman was to secure their reissue in twenty new certificates of 500,000 shares each and one for 600,000 shares. But, said Maxwell, there was to be one significant variation. The new certificates should not mention Macmillan’s ownership. Instead, each certificate was to be issued showing the owner as Bishopsgate Investment Trust (BIT), with the inscribed caveat ‘Purely as a nominee’. Even in Maxwell’s strictly compartmentalized world, Freedman ought to have been suspicious. For BIT was a private company owned by Maxwell. To the inquisitive, the laundering would not have been well disguised.

The legal authority for that exchange was to be an executive committee board meeting to be held in Freedman’s office later on the same day. The participants were three Macmillan directors: Robert and Kevin Maxwell, and David Shaffer, Macmillan’s American president and its chief operating officer in New York. None of the three men, however, was in Manhattan.

The ‘meeting’ occurred at 11.15 a.m. New York time. The two Maxwells were ‘present’ by telephone from London while Shaffer spoke from Stouffers’ Hotel in Westchester, New York State. According to the telephone records, the conference call lasted eleven minutes. One year later, Shaffer would claim to have been duped and would dispute Freedman’s official record. ‘Either I was not told the true purpose of the board meeting,’ he protested, ‘or there was a telephone connection but I was not involved.’

At the end of that day, 5 November 1990, Ellis Freedman handed the twenty-one new share certificates to Ghislaine. By then the youngest Maxwell had varied her plan. Robert Maxwell had agreed that his daughter, instead of flying immediately back to London, could stay in New York overnight. After indulging herself in Manhattan’s shops, Ghislaine met friends for dinner. The following morning, she boarded a Jumbo 747 for the return flight. That night, the envelope was deposited in Robert Maxwell’s personal safe, located in the bathroom of his penthouse apartment on the tenth floor of Maxwell House, adjacent to the Daily Mirror building in Holborn (he had bought the Mirror Group in 1984). He now possessed $200 million, the property of unsuspecting shareholders, for his personal use. That had been precisely his intention.

Two days later, on 8 November, Kevin Maxwell sat in his office, smiling at Julie Maitland, a thirty-year-old banker employed by Crédit Suisse. Over the previous months, Kevin had been assiduously wooing the dark-haired woman, who some would judge in retrospect to be naive and lacking imagination. Like most of the banking fraternity in London, Maitland had eagerly offered her services to the Maxwells and had succumbed to flattery when invited to join what Kevin called the ‘inner circle’ of core banks acting for the family group. Like other bankers, she understood that the Maxwell companies were suffering a financial squeeze. But the truth, cleverly disguised by the Maxwells from the star-struck woman, was worse. The empire was hovering on the verge of bankruptcy and Kevin was hunting for gigantic loans to tide it over. His smiles for Julie Maitland, a wilful adjustment to his customary cold demeanour, were designed to perpetuate that deception and to entice the Swiss bank to lend the Maxwells even more money.

Naturally, the young woman could not act independently. Every discussion with Kevin had been carefully noted and reported in detail, first to her London superiors and then to the bank’s head office in Zurich. ‘The Maxwells want us to understand the private companies,’ Maitland had written plaintively six months earlier about the web of 400 different corporate names through which the Maxwells operated. And there was so much to understand.

Robert Maxwell had always yearned to manage a publicly quoted company, not just for the prestige but, more pertinently, to enable him to play with other people’s money. The Maxwell Communication Corporation was that tool, marred though it was for him by a colossal defect: the legal requirement for public accountability. For a man whose love of publicity went hand in hand with a pathological desire for secrecy, the desire for a publicly quoted company seemed illogical. But the sophist’s empire was designed to fool the honest inquirer. MCC sat at the centre of an utterly confusing and ever changing matrix of private and therefore secret companies. At the very top were a group of Liechtenstein trusts, anonymous and unaccountable owners of the majority of MCC’s shares. In reality, they were controlled by Maxwell. Beneath those Liechtenstein trusts and surrounding MCC like a constellation were 400 private companies of varying sizes and activity, trading with MCC and among themselves, not only in all matters of publishing, communications, printing and technology, but also in property, currencies, gilts and shares.

MCC was the corporate name adopted in 1987, replacing the British Printing and Communications Corporation. The reason, said Maxwell’s spokesman, was to shed the image of ‘dark northern printing halls’, but it was not, claimed Maxwell unconvincingly, ‘an ego trip. It was a decision reluctantly taken.’ To boost MCC’s value, Maxwell had incorporated Pergamon Press, his privately owned and profitable international scientific publishing company which was the foundation of his fortune, into the public company. Maxwell’s own shares in MCC were owned by Pergamon Holdings, which in turn was a subsidiary of the Maxwell Foundation, a private Liechtenstein company which in turn also controlled the privately owned Mirror Group, and which in 1991 was renamed the Robert Maxwell Group. In parallel, there was another Maxwell family company called Headington Hill Investments, ultimately owned by Liechtenstein trusts, which controlled the family’s shares in other private companies.

Maxwell’s purpose in creating this constellation of companies was indisputable. Beyond public scrutiny, he could move shares, assets, cash and debts to satisfy any need, increasingly regardless of rules and laws. So long as MCC was recording gigantic profits in its annual glossy brochure, the City experts did not query his netherworld. But recently a new phrase, its implicit rebuke stirring unease, had entered into the experts’ vocabulary – ‘the quality of MCC’s profits’. There was a suggestion that the empire’s finances were not as sound as their conductor desired the world to believe.

The deliberate confusion created by Robert Maxwell had now become a barrier against the sympathy he required. Maitland’s initial proposal for a loan had been rejected by Zurich. There was more than passing concern about the Maxwells’ ‘rush’ for money and there was some doubt about their ability to repay. The astute feared that they might be ambushed by the confusion.

‘Speculative characteristics’ were mentioned in Zurich and were blamed for the recent drop in MCC’s credit rating from BBB to BB, a warning to banks that their loans were marginally less secure. The doubts which this decline reflected had been fuelled by disparaging newspaper reports about Maxwell’s awkward repayment deadlines and the ‘juggling acts’ he was performing in order to pay off $415 million of debt. To find the cash, he had begun dismantling his empire. Businesses worth $500 million had been quickly sold, arousing suspicion and uncertainty and prompting newspaper comments about strange deals set up to channel money from his private companies to MCC. The very bankers who had rubbed their hands in glee at the prospect of earning fees by helping to finance the creation of the Maxwell empire were being approached to earn more money in arranging sales. In return for commission awarded for selling Maxwell businesses, the banks were expected to lend more money. But, increasingly, they wanted safer security for their loans. That was the reason for Kevin’s smiles at Julie Maitland, the banker.

For years, Robert Maxwell had publicly prided himself on the education of his children. In numerous interviews he had extolled the virtues of the ‘Three Cs’ – concentration, consideration and conciseness. But there was an extra, unpublicized lesson he gave Kevin: the unique importance of a businessman’s relationship with his bankers. For Maxwell, it was said, there were only two relationships: master and servant, and customer and supplier. While most suppliers could be treated with disdain, even contempt, Kevin had been nurtured by his father to cultivate and charm those whose money he wanted to use. Banks, he had learnt, survived and prospered by cultivating a certain trick of confidence, lending more money than they possessed. His father responded by perpetrating a succession of confidence tricks.

So Kevin reacted promptly when he heard from Maitland about her superiors’ reluctance to lend money. Oozing apparent sincerity, he promised: ‘We can provide ample security for the loans.’ The names and quantities of the shares he mentioned as a guarantee for the repayments persuaded Maitland’s superiors to abandon their doubts. He was offering shares in the most prestigious companies – seemingly a testament to Maxwell’s personal wealth hoarded in Liechtenstein. On 7 September Crédit Suisse accordingly granted a £50 million loan for six months. The loan was not to Maxwell Communication Corporation, the publicly quoted company, but to the biggest of Maxwell’s private companies, the Robert Maxwell Group (RMG). Simultaneously, Kevin ordered the appropriate share certificates to be hand-delivered to Maitland’s bank. But there was good reason for the bank to be suspicious of these. On each share certificate, the registered owner was shown as Bishopsgate Investment Management (BIM).

BIM was a private company established by Maxwell to manage the nine pension funds of his 23,400 employees pooled in the Common Investment Fund (CIF) and worth about £727 million. In theory, BIM was the trustee of CIF, which included the Mirror Group Pension Trust (MGPT), but because MGPT’s sixteen directors at the beginning of 1991 included Robert, Kevin and Ian Maxwell (and four trade union representatives), who were also directors of BIM, the self-governance of BIM never existed. Under the regime imposed by Robert and Kevin Maxwell, who were respectively chairman and finance director of BIM, the purchase and sale of BIM’s investments and, equally important, the registration of its share certificates and the location of their physical custody were determined by them rather than by Trevor Cook, the company’s manager (who was also a director).

On the Maxwells’ directions, Cook would either loan BIM’s cash to the Robert Maxwell Group or deposit the money in the account of Bishopsgate Investment Trust (BIT), which the Maxwells could draw at their convenience. BIT had been specially created by Maxwell to act as a private nominee owner of shares without any legal relationship to the pension funds, blurring the actual ownership in the eyes of outsiders. As directors of BIM, BIT and RMG, the Maxwells could effectively constitute themselves a board of directors and transfer the ownership of shares from the pension funds to their private company, using them as collateral for private loans without the knowledge of anyone else. That easy access to loans depended on the size of the pensions’ Common Investment Fund.

Ever since the CIF had been created, Maxwell had sought to persuade, cajole and even threaten his employees not to opt out of their employer’s pension funds. A special twenty-one-minute video, fronted by Maxwell himself seated on a large black leather chair, promised them that the pension schemes would ‘provide good benefits, are financially sound and well run’. To his relief, few had dared to withdraw their money. He could continue to use their millions as his own. No company’s affairs received greater attention from Maxwell than BIM’s.

Maitland ought to have appreciated that BIM managed the pension funds of Maxwell’s empire, but she felt no need to make special inquiries. With each share certificate was a transfer form signed by Kevin and others, including Ian, his thirty-four-year-old brother, showing that ownership of the shares had been transferred to RMG. Maitland did not query why the pension funds should agree to that transfer. Indeed, when on one occasion she saw that a share certificate sent by Kevin was still owned by BIM, she returned it for RMG’s name to be inserted on the transfer form. So, by 8 November 1990, £70 million of pension fund shares had been used to raise money for Maxwell personally. On that same day, Kevin asked Maitland for another private loan. She seemed unsurprised when he offered as collateral a share certificate for 500,000 Berlitz shares. It was, he said, ‘owned by the private side’. Again, Maitland and her superiors had reason to be suspicious.

To repay MCC’s debts in December 1989, 44 per cent of Berlitz had been sold to the public for $131 million. No one had ever suggested that the Maxwells themselves had bought any of those Berlitz shares as a private investment. Nor was their name listed among Berlitz’s registered shareholders. But Maitland would insist that no hint of suspicion ever passed through her mind when Kevin said, ‘These Berlitz shares are privately owned.’ The paperwork for transferring the Berlitz certificate to Maitland had been completed by one of Maxwell’s treasury officials. The Berlitz shares, owned by MCC, the public company, were being used by the Maxwells for their private purposes. By any reckoning, it was highly improper.

Robert Maxwell of course understood the impropriety. Later that week, he signed documents promising not to use the Berlitz share certificates brought back by Ghislaine in any manner without Macmillan’s explicit agreement. His indecipherable scribble would adorn many such documents over the next year. In each case, after he had signed, he would more or less forget the deception. Dishonesty did not trouble him. Throughout his life, he had ignored the norms of morality. Indeed his fortune had been constructed, lost and rebuilt by deliberate transgressions, outwitting and outrunning his opponents regardless of any infringement of the laws. According to the ethics he had learnt as a child, watching smugglers in his Ruthenian border town, the goal was survival and profit, and the consequences to the losers were irrelevant. For Maxwell, the Berlitz transaction had been a minor sideshow at the beginning of another hectic week, working in a moral vacuum within a surreal world.

The atmosphere in the citadel of his empire, the £2 million penthouse apartment on the tenth floor of Maxwell House, was suffocatingly imperious. Polished, double doors led across marble floors into a high-ceilinged hall supported by brown marble Doric columns and lit by glass chandeliers. Beyond, the spectacle of a huge living area decked out with expensive mock-Renaissance tapestry-covered furniture and with carpets patterned in a vast ‘M’ design cautioned any visitor who might be contemplating criticism or challenge. Access to the apartment, in common with all the buildings on the Holborn site, could be gained only by coded plastic cards. Even between neighbouring offices movement was monitored by video cameras. Rigorous security was imposed to protect Robert Maxwell’s secrecy and cushion his paranoia.

The twenty-two-stone proprietor, clothed in bright-blue shirts and dazzling ties, intimidated visitors by his gestures as much as his words, his gargantuan performance humbling those physically and financially less well endowed. The theatricality, the egocentricity and the vanity of the man were unsurpassed. Servile staff offered refreshments, earnest secretaries announced incoming calls from the world’s leaders, and bankers, lawyers and accountants did everything they could to please their client, while his deep, gravelly voice issued curt instructions, allowing no questions. Those who attempted to understand his psychology invariably failed, because both his motives and his reasoning were unique. Utterly consumed by his own self-portrayal as a great man, he was certain of his invincibility, sure that his abilities would overcome the natural consequences of any decision he took. ‘Bob believed he was bigger than the City,’ lamented Johnny Bevan, one of his many brokers. To Maxwell’s gratification, enough of his visitors accepted his self-appraisal. Even his most bitter enemies used the sobriquet ‘Cap’n Bob’ – thereby recognizing, as he saw it, his supreme importance.

On the floor below, the communications centre of his universe, other compliant men and women toiled in the service of the Publisher, otherwise known as the Chairman or RM. Visitors knew that, as in a medieval court, the official job descriptions of these employees often bore little similarity to their actual task. And, again as in a medieval court, dozens of those visitors and employees waited patiently for the opportunity of an audience. From outside, invitations arrived hourly. Most were rejected with the standard computer-template reply that the Chairman regretted that his diary was full for two years. The world’s newspapers, television and radio were constantly monitored for every mention of the man, the precise words faithfully reported in regular faxes. Constantly updated handbooks listed the telephone numbers of every employee, business contact and powerbroker across the world – town home, country house and office – and the speed-dial numbers of those included on a special list. The Publisher delighted in calling employees at the most inopportune moments, demanding not only their attention but their immediate presence. Television screens displayed the trade of MCC shares in seven stock exchanges across Europe and Canada – and were the object of his intense scrutiny. The image was intended to match the substance: not a second could be wasted as the workoholic billionaire controlled his worldwide enterprise.

The empire was run on similar lines to those of Nicolae Ceausescu and Todor Zhivkov, the autocratic communist presidents of Romania and Bulgaria whom Robert Maxwell expensively nurtured. His employees knew only a small part of the scenario, unaware of the implications and the background to the letters and telephone calls flowing to and from their master in those nine languages he claimed to speak. None of the secretaries was allowed to remain employed too long – not even the very pretty ones whose employment the Publisher had particularly requested. No one would be permitted to learn too much, despite the effect on the office’s organization. Nevertheless, their loyalty, devotion and discretion were bought by unusually high salaries, and by fear: fear of Maxwell and fear of losing their jobs and being unable to find similarly lucrative employment. Verbal brutality crushed any opposition. In return for exceptional remuneration, they agreed to sing to their employer’s song sheet. The sole exception, and only a partial one, was Kevin. Fear of Robert Maxwell had been instilled in him from childhood, but by November 1990 his father’s passion for secrecy had been offset by the need for an ally. Kevin had become the cog in the machine essential for his father’s survival.

Bankers, brokers and businessmen in London and New York almost unanimously agreed that Kevin was clever, intelligent, talented, astute and, most importantly, not a bully like his father. Eschewing tantrums and verbal abuse, he had at a young age mastered the intricacies, technicalities and jargon of the financial community. But, with hindsight, the perceptive would be struck by the image of a dedicated son: of medium height, thin, dark, humourless, ruthless, efficient, manipulative, cold and amoral. Kevin acknowledged the source of other qualities in a written appreciation sent to his father: ‘You are my teacher and all my life you have tried to demonstrate the principles underlying every action or inaction even if we were playing roulette or Monopoly … you have given me the sense of excitement of having dozens of balls in the air and the thrill of seeing some of them land right.’ Willingly submitting to the Chairman’s daily demand to vet both his diary and his correspondence for approval and alteration, Kevin would tolerate anything from that quarter for the chance to indulge his love of the Game based upon money and power. ‘I don’t think anyone would ever describe me as being a member of the Salvation Army,’ he would later crow, echoing his father’s statement to truculent and threatening printers in the early 1980s.

For the previous three years he had worked under his father’s supervision, accepting his rules as gospel, not least the injunction never to give up. ‘He enjoyed fighting and enjoyed winning,’ Kevin admiringly observed of Maxwell’s achievement in creating an empire within one generation, while Rothermere, Sainsbury and Murdoch had relied upon inherited money. Kevin positively glowed, relishing both his own family’s wealth and the servility shown towards him.

Yet, despite his power and privilege within the organization, Kevin shrank in his father’s presence. Conditioned by the beatings – psychological rather than physical – which he had received as a child, his eyes would dart agitatedly around, nervously sensing his father’s approach, and sometimes at meetings he would slightly raise his hand to stop someone interfering: ‘Let the old man finish.’ Kevin may well have thought that he could manage the family business honestly, but within recent months either he had veered towards dishonesty or his remaining scruples had been distorted by Robert Maxwell. Many would blame his father’s lifelong dominance for that change, while others would point to his mother’s failure to imbue her youngest son with the moral strength to resist her husband’s demands.

Robert Maxwell had become a collector rather than a manager of businesses. Size, measured in billions of pounds, was his criterion. The excitement of the deal – the seduction, the temptation, the haggling, the consummation and the publicity – had fed his appetite for more. By November 1990, he owned interests in newspapers, publishing, television, printing and electronic databases across the world estimated to be worth £4.2 billion. But the cost of his greed was debts of more than £2.2 billion, and the coffers to repay the loans were empty. This was the background to Ghislaine’s flight to New York to bring back the Berlitz share certificates.

The principal cause of indebtedness was the $3.35 billion spent by Maxwell in 1988 on the ‘Big One’, as his excitable American banker Robert Pirie called it. The money had bought Official Airline Guides (OAG) for $750 million and, more importantly, after an intense and successful public battle with Henry Kravis, the famous pixie-like arbitrageur, the Macmillan publishing group for $2.6 billion. Pirie had throughout stoked Maxwell’s burning sense of triumph.

Pirie, the chief executive of Rothschild Inc., had played on Maxwell’s weaknesses. ‘If you want to be in the media business,’ advised the Rothschild banker, ‘you’ve got to be prepared to pay the price.’ He did not add that he would earn higher fees if Maxwell won. Telling his client, ‘You’re paying top dollar,’ Pirie did not discourage him from going for broke. Maxwell’s self-imposed deadline for joining the Big Ten League, alongside his old rival Rupert Murdoch, would expire in just thirteen months. Intoxicated by the publicity of spending $3 billion, he crossed the threshold without considering the consequences. ‘Plays him like a puppet,’ sniped one who was able to observe Pirie’s artful sycophancy. To Pirie, Maxwell had not overpaid. There were, in the jargon of that frenetic era, ‘enormous synergies’ and the Publisher himself did not even consider his plight as a debtor owing $3 billion. After all, Pirie boasted, ‘Maxwell had no credibility problem with the lending banks.’ But the Rothschild banker disclaimed any responsibility for the other deal. ‘He paid too much for OAG,’ he later volunteered, adding unconvincingly, ‘The deal was done by Maxwell, not me.’

Forty-four banks had lent Maxwell $3 billion, hailed by all as proof of his return to respectability. Astonishingly, the giant sum was not initially secured against any assets. He could lose all that cash without more than a blink. The interest rates, moreover, were a derisory 0.5 per cent over base rate. The deal was a phenomenal bargain negotiated through Crédit Lyonnais and Samuel Montagu by Richard Baker, MCC’s gruff deputy managing director, who had been born in Shepherds Bush, west London. Maxwell had inherited Baker when he bought the British Printing Corporation (BPC), Britain’s biggest printers, in an exquisite dawn raid in 1980.

Maxwell’s victory was more than commercial. Despite his infamous branding as a pariah by British government inspectors in 1971, which had cast him into the wilderness, Maxwell had re-established his respectability and acceptability among most in the City. Here was the reincarnation of what had long ago been unaffectionately dubbed ‘The Bouncing Czech’. Leading the supporters was the Nat West Bank, his bankers since 1945, who were impressed by the way their client had crushed the trade unions at BPC, restoring the company to robust profitability. Now the ‘Jumbo Loan’ was the world financial community’s statement of faith in Maxwell. ‘All the banks were clamouring to join the party,’ recalled Ron Woods, Maxwell’s soft-spoken Welsh tax adviser and a director of MCC. Bankers judged MCC to be not only an exciting but a safe company. Former enemies had become allies – and over the years he had collected many enemies. Their numbers had multiplied after 1969 when he had sold Pergamon Press, his scientific publishing company, to Saul Steinberg, a brash young New York tycoon. Since Maxwell was a publicity-seeking, high-profile Labour member of parliament, the deal had attracted unusual attention. Pergamon, Maxwell’s brainchild, was a considerable international success, elevating its owner into the rarefied world of socialist millionaires.

But within weeks the take-over was plunged in crisis. Steinberg’s executives had discovered that Maxwell’s accounts were fraudulent, shamelessly contrived to project high profits and conceal losses. In the ensuing storm of opprobrium, Maxwell was castigated by the Take-Over Panel, lost control of Pergamon and was investigated by two inspectors appointed by the Department of Trade and Industry. In their first report published in 1971, the inspectors, after reminding readers that Maxwell had been censured in 1954 by an official receiver for trading as a book wholesaler while insolvent, revealed that his confidently paraded finances were exercises in systematic dishonesty. Their final conclusion was to haunt Maxwell for the rest of his life:

He is a man of great energy, drive and imagination, but unfortunately an apparent fixation as to his own abilities causes him to ignore the views of others if these are not compatible.… The concept of a Board being responsible for policy was alien to him.

We are also convinced that Mr Maxwell regarded his stewardship duties fulfilled by showing the maximum profits which any transaction could be devised to show. Furthermore, in reporting to shareholders and investors, he had a reckless and unjustified optimism which enabled him on some occasions to disregard unpalatable facts and on others to state what he must have known to be untrue.…

We regret having to conclude that, notwithstanding Mr Maxwell’s acknowledged abilities and energy, he is not in our opinion a person who can be relied upon to exercise proper stewardship of a publicly quoted company.

Even before that excruciating judgment was published, most City players had deserted Maxwell or refused his business. Ostracized, he did not begin to shrug off his pariah status until July 1980, when he succeeded in his take-over bid for the near-bankrupt British Printing Corporation (partly financed by the National Westminster bank). Within two years, his brutal but skilful management had transformed Britain’s biggest printers into a profitable concern, laying the foundations for his purchase of the Mirror Group in 1984.

Building on that apparent respectability, the financial community had cast aside their doubts and contributed to the Jumbo Loan. Among his closest advisers were Rothschilds, his bankers, who had shunned him after 1969; his accountants were Coopers and Lybrand, one of the world’s biggest partnerships; and among his lawyers was Bob Hodes of Wilkie Farr Gallagher, who had led the litigation against him in 1969. For Hodes, a scion of New York’s legal establishment, Maxwell had become ‘a likeable rogue who appeared to enjoy the game’. Like all the other professionals excited by the sound of gunfire, Hodes was confident that he could resist any pressure from Maxwell to bend the rules.

A celebration lunch when the Jumbo Loan had been rearranged was held at Claridge’s on 23 October 1989 by Fritz Kohli, of the Swiss Bank Corporation. The champagne had flowed as successive toasts and speeches showered mutual congratulations upon Maxwell and his banks. The Publisher had been gratified, especially by the presence of Senator John Tower and Walter Mondale, the former US vice-president, both of them anxious to become his paid lobbyists. Everyone was excited by the star because he was a dealmaker and deals generated headlines and income. Few bothered to consider that behind the deals there was little evidence of any considered strategy or of diligent management. But even then, unknown to the bankers, the consequences of that weakness were already apparent and Maxwell’s grandiose ambitions were faltering. Unexpectedly high interest rates, a worldwide recession and a fall in stock market prices were gradually devastating his finances.

One option for salvation was to adopt Rupert Murdoch’s solution. Maxwell’s bugbear had confessed his financial problems to his banks and had renegotiated the repayment of his $7.6 billion loans. Maxwell rejected that remedy. The wilfully blind would blame his vanity but, in retrospect, others understood his secret terror of having the banks inspect his accounts. The result would have been not a sensible rearrangement but merciless castration. Ever since 1947 when he had first launched himself into business, Maxwell had massaged profits, concealed losses and siphoned off cash by running several companies in parallel and organizing spurious deals within his empire. This manipulation was possible because only he, at the centre of the web, saw the total picture. Renowned as a master-juggler, he was blessed with a superb memory, perfectly focused amid the deliberate confusion, ordering obedient and myopic accountants to switch money and companies through a bewildering jungle of relationships.

By 1990, those trades had come to infect the interlocking associations between the complex structure of the tycoon’s 400 private companies and Maxwell Communication Corporation, the publicly quoted company. The disease was his insatiable ambition. He wanted to be rich, famous, powerful, admired, respected and feared. His empire was to reflect those desires. The means to that end were MCC’s ever increasing profits, which in turn determined the company’s share price. That relationship was the triple foundation of his survival, his dishonesty and his downfall. Whenever the profits were in danger, Maxwell resorted to a ruse which exposed his instinct for fraud: he pumped his personal money into the public company. Since 1987, he had bought with private funds bits of MCC at inflated prices to keep its profits and share price high. Invariably, he was buying the unprofitable bits.

To pay for that extravagance, Maxwell had borrowed money. By 1989, his private empire – unknown to outsiders – was on the verge of insolvency. As security for the loans, he had pledged to banks his 60 per cent stake in MCC. Unfortunately for him, by November 1990 growing suspicion of his accounts and critical newspaper reports had triggered a slide in the value of MCC shares, which over three years had fallen from 387p to a new low of 142p. The latest discontent in early October intensified Maxwell’s crisis. As his financial problems grew and MCC’s share price fell, the banks demanded more security for their loans. Maxwell’s solution was radical and initially secret. To keep the share price high, he had undertaken two bizarre and contradictory strategies. First, MCC was paying shareholders high dividends to make the shares an attractive investment. But the Publisher’s insoluble problem was that the dividends which MCC paid out were actually higher than the company’s profits. In 1989, the dividend cost £112.3 million, while the profits from normal trading were £97.3 million. Among the necessary costs of maintaining that charade was payment of advance corporation tax which in 1989 amounted to £17.6 million. The extraneous tax cost for the same ruse in 1990 was £98.8 million on adjusted trading profits of £71.1 million.

Maxwell’s second strategy to keep the share price high was to buy MCC shares personally. Since 1989 he had quietly spent £100 million in that venture. The solution bred several problems, not least that he soon ran out of cash. His response was to borrow more money to buy his own shares.

To their credit, both father and son could still rely upon the large residue of goodwill among leading bankers in all the major capitals – London, New York, Tokyo, Zurich, Paris and Frankfurt – and upon those bankers’ conviction that MCC’s debts were manageable. Their guarantee, they believed, was the vast private fortune of Robert Maxwell’s privately owned companies secreted in Liechtenstein. Although none of those bankers had ever seen the accounts of his Liechtenstein trusts, they believed they had no reason to doubt the Publisher’s boasts. Maxwell continued to encourage their credulity, while using banks in the Dutch Antilles and Cayman Islands as the true, secret receptacles of his wealth.

Among that army of bankers was Andrew Capitman, an ambitious manager of Bankers Trust, the American bank. Two years earlier, Capitman had purposefully moved to London to earn his fortune pleasing Maxwell in the course of completing thirty-eight separate transactions. Not surprisingly, he enjoyed the Concorde and first-class flights across the world, the heaps of caviar and champagne, all funded by his client. He too assumed that the Liechtenstein billions were the source of Maxwell’s cash for another unusual transaction to be completed at noon on 5 November 1990, just three hours before the seizure of the Berlitz shares.

Descending from his office on the ninth floor, Maxwell hurriedly chaired an extraordinary general meeting of MCC in the Rotunda on the mezzanine floor of the ugly Mirror headquarters in Holborn. The topic was one of Maxwell’s more expensive inter-company deals. Two Canadian companies, owned by MCC, were to be sold. And, because the recession meant that the price offered by others would be low, Maxwell proposed himself (or rather the Mirror Group, which he still privately owned) as the purchaser. Capitman understood that Maxwell’s strategy in that bizarre arrangement was to boost MCC’s profits and he had independently valued the two Canadian paper and print companies, Quebecor and Donohue, at a high £135 million. In return for offering a ‘slam-dunk’ generous valuation, the banker pocketed a cool $700,000 fee.

Capitman’s assumption that the £135 million was drawn from the Liechtenstein billions was erroneous. The true source of the £400 million Maxwell required to buy a succession of companies in similar deals from MCC during the following year was his own private loans – an unsustainable burden on his finances.

Among his most important lenders was Goldman Sachs, the giant New York bank. Of the many Goldmans executives with whom Maxwell spoke, none seemed more important that Eric Sheinberg, a fifty-year-old senior partner and graduate of Pennsylvania University. Sheinberg arrived in London in 1987 after a profitable career in New York and Singapore. For the hungry young traders in Goldman Sachs’ London office, which was sited near Maxwell’s headquarters, Sheinberg not only provided leadership but inspired trust. Trained by Gus Levy, a legendary and charismatic Wall Street trader, he was renowned for having made a killing trading convertible equities. ‘Eric’s a trader’s trader,’ was the admiring chant among his colleagues. Eric, it was said, had once confided that Goldmans was his first love: his formidable wife had to take second place. After losing successive internal political battles and suffering some discomfort after a colleague had been indicted for insider trading, Sheinberg, an inventor of financial products for the unprecedented explosion in the bull market, was now seeking the business of London’s leading players in the wake of the City’s deregulatory Big Bang. Few were bigger than Maxwell.

Goldmans already enjoyed a relationship with Maxwell. In 1984, the bank had rented office space from him in Holborn, and Sheinberg had organized the financing of his purchase of the Philip Hill Investment Trust in 1986. Despite some misgivings, Goldmans had also welcomed the business of floating 44 per cent of Berlitz in 1989, although the negotiations over the price had provoked deep antagonism, especially against Kevin. To prove his macho credentials, the son had telephoned the banker responsible at 4 a.m. New York time, to quibble about the price. ‘Both Maxwells behaved appallingly,’ recalled one of those involved. ‘Kevin worst of all. We soon hated them.’

Yet Maxwell’s business was too good to reject. The echo of the lawyers’ cries in Maxwell House – ‘Bob’s been shopping!’ – whenever the Chairman’s settlement agreements arrived from stockbroking firms, encouraged brokers like Sheinberg to seek his lucrative business. Although Sheinberg was renowned for his dictum, ‘There are no friends in the business, and I don’t trade on the basis of friendship,’ his staff in London noticed an unusual affinity between him and Maxwell. Some speculated that the link lay in their mutual interest in Israel, while others assumed it was just money. Maxwell was a big, brave gambler, playing the markets whether with brilliant insight or recklessness for $100 million and more a time, and Sheinberg was able to offer expertise, discretion and – fuelling his colleagues’ gossip – the unusual practice of clearing his office whenever Maxwell telephoned. Their kinship extended, so the gossip suggested, to Sheinberg’s readiness to overnight in Maxwell’s penthouse, to ride in Maxwell’s helicopter and even to use Maxwell’s VIP customs facilities at Heathrow airport – suggestions which Sheinberg denied.

Acting as a principal and occasionally as an adviser, Sheinberg had already undertaken a series of risks which had pleased Maxwell. On the bank’s behalf, the broker had bought 25 million MCC shares and, in controversial circumstances in August 1990, as MCC’s price hovered around 170p, he had bought another 15.65 million shares as part of a gamble with Maxwell that the price would rise. Maxwell had channelled the money for that transaction through Corry Stiftung, one of his many Liechtenstein trusts. In the event, the Publisher had lost his gamble and Goldman Sachs had been officially reprimanded for breaking the City’s disclosure regulations. That, however, Sheinberg blamed upon Goldmans’ back office, since fulfilling the legal requirements was not his responsibility. Nevertheless, by November 1990, the bank was holding 47 million MCC shares, a testament of faith which could be judged as either calculated or reckless.