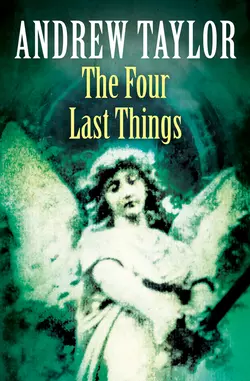

The Four Last Things

Andrew Taylor

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 122.57 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 19.09.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: The first novel in Andrew Taylor’s ground-breaking Roth trilogy, which was adapted into the acclaimed drama Fallen Angel. A tense psychological thriller for fans of S J Watson.Little Lucy Appleyard is snatched from her child minder’s on a cold winter afternoon, and the nightmare begins. When Eddie takes her home to beautiful, child-loving Angel, he knows he’s done the right thing. But Lucy’s not like their other visitors, and unwittingly she strikes through Angel’s defences to something both vulnerable and volatile at the core.To the outside world Lucy has disappeared into a black hole with no clues to her whereabouts…until the first grisly discovery in a London graveyard. More such finds are to follow, all at religious sites, and, in a city haunted by religion, what do these offerings signify?All that stands now between Lucy and the final sacrifice are a CID sergeant on the verge of disgrace and a woman cleric – Lucy’s parents – but how can they hope to halt the evil forces that are gathering around their innocent daughter?