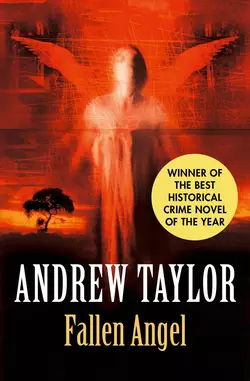

Fallen Angel

Andrew Taylor

Like an archaeological dig, The Roth Trilogy strips away the past to reveal the menace lurking in the present: ‘Taylor has established a sound reputation for writing tense, clammy novels that perceptively penetrate the human psyche’ – Marcel Berlins, The TimesThe shadow of past evil hangs over the present in Andrew Taylor's Roth Trilogy as he skilfully traces the influences that have come to shape the mind of a psychopath.Beginning, in The Four Last Things, with the abduction of little Lucy Appleyard and a grisly discovery in a London graveyard, the layers of the past are gradually peeled away through The Judgement of Strangers and The Office of the Dead to unearth the dark and twisted roots of a very immediate horror that threatens to explode the serenity of Rosington's peaceful Cathedral Close.

ANDREW TAYLOR

FALLEN ANGEL

THE ROTH TRILOGY

COPYRIGHT (#ulink_47f07238-8811-5a3a-97d8-7ff5e575391a)

This is entirely a work of fiction. Any references to real people, living or dead, real events, businesses, organizations and localities are intended only to give the fiction a sense of reality and authenticity. All names, characters and incidents are either the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and their resemblance, if any, to real-life counterparts is entirely coincidental.

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published by

HarperCollinsPublishers 2014

Copyright © Andrew Taylor 2014

Andrew Taylor asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2014 Cover illustration created from photographs © Pauline Thomas/Millennium Images (woman); Special Photographers Library/Ian Glover (landscape); Special Photographers Library/ Robert Mann (wings)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication.

Source ISBN: 9780007502011, 9780007502028, 9780007502035

Ebook Edition © JUNE 2014 ISBN: 9780007368792

Version: 2017-05-19

CONTENTS

Cover (#u9d8b649f-f573-5274-ba87-3c04d5dd1e2f)

Title Page (#uf3973c6d-a035-583a-8e5b-1dbd12887cdb)

Copyright (#u214d6f98-4c26-57ca-a6fb-25fcbe2646af)

The Four Last Things (#uc2d7e71a-4a04-5080-b377-b6b80cebb0e8)

The Judgement of Strangers (#litres_trial_promo)

The Office of the Dead (#litres_trial_promo)

Keep Reading (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Also by the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

(#ulink_5398a951-24fb-561f-a6d4-c2c0ed60c820)

ANDREW TAYLOR

THE FOUR LAST THINGS

COPYRIGHT (#ulink_c6e240fa-e335-54d9-99a5-e82699fde483)

This is entirely a work of fiction. Any references to real people, living or dead, real events, businesses, organizations and localities are intended only to give the fiction a sense of reality and authenticity. All names, characters and incidents are either the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and their resemblance, if any, to real-life counterparts is entirely coincidental.

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers 1997

Copyright © Andrew Taylor 1997

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2013 Cover photography © Mark Pennington

Andrew Taylor asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication.

Source ISBN: 9780007105113

Ebook Edition JUNE 2013 ISBN: 9780007502011

Version: 2017-05-19

CONTENTS

Cover (#uc2d7e71a-4a04-5080-b377-b6b80cebb0e8)

Title Page (#ulink_fbf9ebe5-f051-5c9b-be4f-2a78d50f7877)

Copyright (#ulink_b013aef9-21a3-5d7d-b0be-539bcce56ec3)

Prologue (#ulink_d6a85d03-0406-58ed-807f-958395ae0720)

1 (#ulink_3df03f4b-e0c0-5170-877a-9e47302b1416)

2 (#ulink_be6eebab-f47b-5882-8128-4151d3618445)

3 (#ulink_bf78be4d-eb8a-500b-a2a0-f7758f3009f1)

4 (#ulink_f8e891a9-fe79-5406-9483-256f46a78cf5)

5 (#ulink_4cc4d6dd-922d-5252-81e4-9602a88a8445)

6 (#ulink_072767c4-8e8e-504c-a82a-5eda6f1aae74)

7 (#ulink_513c9e7c-e379-5528-a430-fc2eac204b26)

8 (#ulink_67f47d8b-a0d8-50c6-bfa9-71855a745cac)

9 (#ulink_445b64a1-37fb-5359-a34b-aaa16897d5b0)

10 (#ulink_1ce3c3f2-d897-537f-ab27-f3441afac2d4)

11 (#litres_trial_promo)

12 (#litres_trial_promo)

13 (#litres_trial_promo)

Epilogue (#litres_trial_promo)

PROLOGUE (#ulink_e0ebcafd-ef17-571a-9999-62ef8549b4ec)

‘In brief, we all are monsters, that is, a composition of Man and Beast …’

Religio Medici, I, 55

All his life Eddie had believed in Father Christmas. In childhood his belief had been unthinking and literal; he clung to it for longer than his contemporaries and abandoned it only with regret. In its place came another conviction, another Father Christmas: less defined than the first and therefore less vulnerable.

This Father Christmas was a private deity, the source of small miracles and unexpected joys. This Father Christmas – who else? – was responsible for Lucy Appleyard.

Lucy was standing in the yard at the back of Carla Vaughan’s house. Eddie was in the shadows of the alleyway, but Lucy was next to a lighted window and there could be no mistake. It was raining, and her dark hair was flecked with drops of water that gleamed like pearls. The sight of her took his breath away. It was as if she were waiting for him. An early present, he thought, gift-wrapped for Christmas. He moved closer and stopped at the gate.

‘Hello.’ He kept his voice soft and low. ‘Hello, Lucy.’

She did not reply. Nor did she seem to register his use of her name. Her self-possession frightened Eddie. He had never been like that and never would be. For a long moment they stared at each other. She was wearing what Eddie recognized as her main outdoor coat – a green quilted affair with a hood; it was too large for her and made her look younger than she was. Her hands, almost hidden by the cuffs, were clasped in front of her. He thought she was holding something. On her feet she wore the red cowboy boots.

Behind her the back door was closed. There were lights in the house but no sign of movement. Eddie had never been as close to her as this. If he leant forward, and stretched out his hand, he would be able to touch her.

‘Soon be Christmas,’ he said. ‘Three and a half weeks, is it?’

Lucy tossed her head: four years old and already a coquette.

‘Have you written to Santa Claus? Told him what you’d like?’

She stared at him. Then she nodded.

‘So what have you asked him for?’

‘Lots of things.’ She spoke well for her age, articulation clear, the voice well-modulated. She glanced back at the lighted windows of the house. The movement revealed what she was carrying: a purse, too large to be hers, surely? She turned back to him. ‘Who are you?’

Eddie stroked his beard. ‘I work for Father Christmas.’ There was a long silence, and he wondered if he’d gone too far. ‘How do you think he gets into all those houses?’ He waved his hand along the terrace, at a vista of roofs and chimneys, outhouses and satellite dishes; the terrace backed on to another terrace, and Eddie was standing in the alley which ran between the two rows of backyards.

Lucy followed the direction of his wave with her eyes, raising herself on the toes of one foot, a miniature ballerina. She shrugged.

‘Just think of them. Millions of houses, all over London, all over the world.’ He watched her thinking about it, her eyes growing larger. ‘Chimneys aren’t much use – hardly anyone these days has proper fires, do they? But he has other ways in and out. I can’t tell you about that. It’s a secret.’

‘A secret,’ she echoed.

‘In the weeks before Christmas, he sends me and a few others around to see where the problems might be, what’s the best way in. Some houses are very difficult, and flats can be even worse.’

She nodded. An intelligent child, he thought: she had already begun to think out the implications of Santa Claus and his alleged activities. He remembered trying to cope with the problems himself. How did a stout gentleman carrying a large sack manage to get into all those homes on Christmas Eve? How did he get all the toys in the sack? Why didn’t parents see him? The difficulties could only be resolved if one allowed him magical, or at least supernatural, powers. Lucy hadn’t reached that point yet: she might be puzzled but at present she lacked the ability to follow her doubts to their logical conclusions. She still lived in an age of faith. Faced with something she did not understand, she would automatically assume that the failure was hers.

Eddie’s skin tingled. His senses were on the alert, monitoring not only Lucy but the houses and gardens around them. It was early evening; at this time of year, on the cusp between autumn and winter, darkness came early. The day had been raw, gloomy and damp. He had seen no one since he turned into the alleyway.

Traffic passed in the distance; the faint but insistent rhythm of a disco bass pattern underpinned the howl of a distant siren, probably on the Harrow Road; but here everything was quiet. London was full of these unexpected pools of silence. The streetlights were coming on and the sky above the rooftops was tinged an unhealthy yellow.

‘You look as if you’re going out.’ Eddie knew at once that this had been the wrong thing to say. Once again Lucy glanced back at the house, measuring the distance between herself and the back door. Hard on the heels of this realization came another: perhaps she wasn’t afraid of Eddie but of outraged authority on the other side of that door.

He blurted out, ‘It’s a nice evening for a walk.’ Idiotic or not, the remark seemed to have a relaxing effect on Lucy. She turned back to him, peering up at his face.

He rested his arms along the top of the gate. ‘Are you going out?’ he asked, politely interested, talking as one adult to another.

Again the toss of the head: this time inviting a clash of wills. ‘I’m going to Woolworth’s.’

‘What are you going to buy?’

She lowered her voice. ‘A conjur—’ The word eluded her and she swiftly found a substitute: ‘A magic set. So I can do tricks. See – I’ve got my purse.’ She held it out: a substantial oblong, made for the handbag not the pocket; designed for an adult, not a child.

Eddie took a long, deep breath. Suddenly it was hard to breathe. There always came a point when one crossed the boundary between the permissible and the forbidden. He knew that Angel would be furious. Angel believed in careful preparation, in following a plan; that way, she said, no one got hurt. She hated anything which smacked of improvisation. His heart almost failed him at the thought of her reaction.

Yet how could he turn away from this chance? Lucy was offering herself to him, his Christmas present. Had anyone ever had such a lovely present? But what if someone saw them? He was afraid, and the fear was wrapped up with desire.

‘Is it far?’ Lucy asked. ‘Woolworth’s, I mean.’

‘Not really. Are you going there now?’

‘I might.’ Again she glanced back at the house. ‘The gate’s locked. There’s a bolt.’

The gate was a little over four feet high. Eddie put his left hand over and felt until he found the bolt. He had to work it to and fro to loosen it in its socket; it was too stiff for a child of Lucy’s age, even if she could have reached it. At last it slid back, metal smacking on metal. He tensed, waiting for opening doors, for faces at the windows, for dogs to bark, for angry questions. He guessed from her stillness that Lucy too was waiting. Their shared tension made them comrades.

Eddie pushed the gate: it swung into the yard with a creak like a long sigh. Lucy stepped backwards. Her face was pale, intent and unreadable.

‘Are you coming?’ He made as if to turn away, knowing that the last thing he must seem was threatening. ‘I’ll give you a ride there in my van if you want. We’ll be back in a few minutes.’

Lucy looked back at the house again.

‘Don’t worry about Carla. You’ll be back before she notices you’re gone.’

‘You know Carla?’

‘Of course I do.’ Eddie was on safer ground here. ‘I told you that I worked for Father Christmas. He knows everything. I saw you with her yesterday in the library. Do you remember? I winked at you.’

The quality of Lucy’s silence changed. She was curious now, perhaps relieved.

‘And I saw you at St George’s the other Sunday, too. Your mummy’s called Sally and your daddy’s called Michael.’

‘You know them too?’

‘Father Christmas knows everyone.’

Still she lingered. ‘Carla will be cross.’

‘She won’t be cross with either of us. Not if she wants any Christmas presents this year.’

‘Carla wants to win the Lottery for Christmas. I know. I asked her.’

‘We’ll have to see.’

Eddie took a step down the alleyway. He stopped, turned back and held out his hand to Lucy. Without a backward glance, she slipped through the open gate and put her hand in his.

1 (#ulink_79f6eae6-d518-50cd-9886-aa433b6d6a4d)

‘Who can but pity the merciful intention of those hands that do destroy themselves? the Devil, were it in his power, would do the like …’

Religio Medici, I, 51

‘God does not change,’ said the Reverend Sally Appleyard. ‘But we do.’

She stopped and stared down the church. It wasn’t that she didn’t know what to say next, nor that she was afraid: but time itself was suddenly paralysed. As time could not move, all time was present.

She had had these attacks since childhood, though less frequently since she had left adolescence behind; often they occurred near the start of an emotional upheaval. They were characterized by a dreamlike sense of inevitability – similar, Sally suspected, to the preliminaries to an epileptic fit. The faculty might conceivably be a spiritual gift, but it was a very uncomfortable one which appeared to serve no purpose.

Her nervousness had vanished. The silence was total, which was characteristic. No one coughed, the babies were asleep and the children were quiet. Even the traffic had faded away. August sunshine streamed in an arrested waterfall of light through the windows of the south-nave aisle and the south windows of the clerestory. She knew beyond any doubt that something terrible was going to happen.

The two people Sally loved best in the world were sitting in the second pew from the front, almost directly beneath her. Lucy was sitting on Michael’s lap, frowning up at her mother. On the seat beside her was a book and a small cloth doll named Jimmy. Michael’s head was just above Lucy’s. When you saw their heads so close together, it was impossible to doubt the relationship between them: the resemblance was easy to see and impossible to analyse. Michael had his arms locked around Lucy. He was staring past the pulpit and the nave altar, up the chancel to the old high altar. His face was sad, she thought: why had she not noticed that before?

Sally could not see Derek without turning her head. But she knew he would be staring at her with his light-blue eyes fringed with long sandy lashes. Derek disturbed her because she did not like him. Derek was the vicar, a thin and enviably articulate man with a very pink skin and hair so blond it was almost white.

Most of the other faces were strange to her. They must be wondering why I’m just standing here, Sally thought, though she knew from experience that these moments existed outside time. In a sense, they were all asleep: only she was awake.

The pressure was building up. She wasn’t sure whether it was inside her or outside her; it didn’t matter. She was sweating and the neatly printed notes for her sermon clung to her damp fingers.

As always in these moments, she felt guilty. She stared down at her husband and daughter and thought: if I were spiritually strong enough, I should be able to stop this or to make something constructive out of it. Despair flooded through her.

‘Your will be done,’ she said, or thought she said. ‘Not mine.’

As if the words were a signal, time began to flow once more. A woman stood up towards the back of the church. Sally Appleyard braced herself. Now it was coming, whatever it was, she felt better. Anything was an improvement on waiting.

She stared down the nave. The woman was in her sixties or seventies, small, slight and wearing a grubby beige raincoat which was much too large for her. She clutched a plastic bag in her arms, hugging it against her chest as if it were a baby. On her head was a black beret pulled down over her ears. A ragged fringe of grey, greasy hair stuck out under the rim of the beret. It was a warm day but she looked pinched, grey and cold.

‘She-devil. Blasphemer against Christ. Apostate.’ As she spoke, the woman stared straight at Sally and spittle, visible even at a distance, sprayed from her mouth. The voice was low, monotonous and cultivated. ‘Impious bitch. Whore of Babylon. Daughter of Satan. May God damn you and yours.’

Sally said nothing. She stared at the woman and tried to pray for her. Even those who did not believe in God were willing to blame the shortcomings of their lives on him. God was hard to find so his ministers made convenient substitutes.

The woman’s lips were still moving. Sally tried to blot out the stream of increasingly obscene curses. In the congregation, more and more heads craned towards the back of the church. Some of them belonged to children. It wasn’t right that children should hear this.

She was aware of Michael standing up, passing Lucy to Derek’s wife in the pew in front, and stepping into the aisle. She was aware, too, of Stella walking westwards down the nave towards the woman in the raincoat. Stella was one of the churchwardens, a tall, stately black woman who appeared never to be in a hurry.

Everything Sally saw, even Lucy and Michael, seemed both physically remote and to belong to a lesser order of importance. It impinged on her no more than the flickering images on a television set with the sound turned down. Her mind was focused on the woman in the beret and raincoat, not on her appearance or what she was saying but on the deeper reality beneath. Sally tried with all her might to get through to her. She found herself visualizing a stone wall topped with strands of barbed wire.

Michael and Stella had reached the woman now. Like an obliging child confronted by her parents, she held out her arms, giving one hand to Michael and one to Stella; she closed her mouth at last but her eyes were still on Sally. For an instant Michael, Stella and the woman made a strangely familiar tableau: a scene from a Renaissance painting, perhaps, showing a martyr about to be dragged uncomplainingly to the stake, with her eyes staring past the invisible face of the artist, standing where her accuser would be, to the equally invisible heavenly radiance beyond.

The tableau destroyed itself. Stella scooped up the carrier bag with her free hand. She and Michael drew the woman along the pew and walked with her towards the west door. Their shoes clattered on the bright Victorian tiles and rang on the central-heating gratings. The woman did not struggle but she twisted herself round until she was walking sideways. This allowed her to turn her head as far as she could and continue to stare at Sally.

The heavy oak door opened. The sound of traffic poured into the church. Sally glimpsed sunlit buildings, black railings and a blue sky. The door closed with a dull, rolling boom. For an instant the boom didn’t sound like a closing door at all: it was more like the whirr of great wings beating the air.

Sally took a deep breath. As she exhaled, a picture filled her mind: an angel, stern and heavily feathered, the detail hard and glittering, the wings flexing and rippling. She pushed the picture away.

‘God does not change,’ she said again, her voice grim. ‘But we do.’

Afterwards Derek said, ‘These days we need bouncers, not churchwardens.’

Sally turned to look at him combing his thinning hair in the vestry mirror. ‘Seriously?’

‘We wouldn’t be the first.’ His reflection gave her one of his pastoral smiles. ‘I don’t mean it, of course. But you’ll have to get used to these interruptions. We get all sorts in Kensal Vale. It’s not some snug little suburb.’

This was a dig at Sally’s last parish, a predominantly middle-class enclave in the diocese of St Albans. Derek took a perverse pride in the statistics of Kensal Vale’s suffering.

‘She needs help,’ Sally said.

‘Perhaps. I suspect she’s done this before. There have been similar reports elsewhere in the diocese. Someone with a bee in her bonnet about women in holy orders.’ He slipped the comb into his pocket and turned to face her. ‘Plenty of them around, I’m afraid. We just have to grin and bear it. Or rather them. We get worse interruptions than dotty old ladies, after all – drunks, drug addicts and nutters in all shapes and sizes.’ He smiled, pulling back his lips to reveal teeth so perfect they looked false. ‘Maybe bouncers aren’t such a bad idea after all.’

Sally bit back a reply to the effect that it was a shame they couldn’t do something more constructive. It was early days yet. She had only just started her curacy at St George’s, Kensal Vale. Salaried parish jobs for women deacons were scarce, and she would be a fool to antagonize Derek before her first Sunday was over. Perhaps, too, she was being unfair to him.

She checked her appearance in the mirror. After all this time the dog collar still felt unnatural against her neck. She had wanted what the collar symbolized for so long. Now she wasn’t sure.

Derek was too shrewd a manager to let dislike fester unnecessarily. ‘I liked your sermon. A splendid beginning to your work here. Do you think we should make more of the parallels between feminism and the antislavery movement?’

A few minutes later Sally followed him through the church to the Parish Room, which occupied what had once been the Lady Chapel. Its conversion last year had been largely due to Derek’s gift for indefatigable fund-raising. About thirty people had lingered after the service to drink grey, watery coffee and meet their new curate.

Lucy saw her mother first. She ran across the floor and flung her arms around Sally’s thighs.

‘I wanted you,’ Lucy muttered in an accusing whisper. She was holding her doll Jimmy clamped to her nose, a sign of either tiredness or stress. ‘I wanted you. I didn’t like that nasty old woman.’

Sally patted Lucy’s back. ‘I’m here, darling, I’m here.’

Stella towed Michael towards them. She was in her forties, a good woman, Sally suspected, but one who dealt in certainties and liked the sound of her own voice and the authority her position gave her in the affairs of the parish. Michael looked dazed.

‘We were just talking about you,’ Stella announced with pride, as though the circumstance conferred merit on all concerned. ‘Great sermon.’ She dug a long forefinger into Michael’s ribcage. ‘I hope you’re cooking the Sunday lunch after all that.’

Sally took the coffee which Michael held out to her. ‘What happened to the old woman?’ she asked. ‘Did you find out where she lives?’

Stella shook her head. ‘She just kept telling us to go away and leave her in peace.’

‘Ironic, when you think about it,’ Michael said, apparently addressing his cup.

‘And then a bus came along,’ Stella continued, ‘and she hopped on. Short of putting an armlock on her, there wasn’t much we could do.’

‘She’s not a regular, then?’

‘Never seen her before. Don’t take it to heart. Nothing personal.’

Lucy tugged Sally’s arm, and coffee slopped into the saucer. ‘She should go to prison. She’s a witch.’

‘She’s done nothing bad,’ Sally said. ‘She’s just unhappy. You don’t send people to prison for being unhappy, do you?’

‘Unhappy? Why?’

‘Unhappy?’ Derek Cutter appeared beside Stella and ruffled Lucy’s hair. ‘A young lady like you shouldn’t be unhappy. It’s not allowed.’

Pink and horrified, Lucy squirmed behind her mother.

‘Sally tells me this was once the Lady Chapel,’ Michael said, diverting Derek’s attention from Lucy. ‘Times change.’

‘We were lucky to be able to use the space so constructively. And in keeping with the spirit of the place, too.’ Derek beckoned a middle-aged man, small and sharp-eyed, a balding cherub. ‘Sally, I’d like you to meet Frank Howell. Frank, this is Sally Appleyard, our new curate, and her husband Michael.’

‘Detective Sergeant, isn’t it?’ Howell’s eyes were red-rimmed.

Michael nodded.

‘There’s a piece about your lady wife in the local rag. They mentioned it there.’

Derek coughed. ‘I suppose you could say all of us are professionally nosy in our different ways. Frank’s a freelance journalist.’

Howell was shaking hands with Stella. ‘For my sins, eh?’

‘In fact, Frank was telling me he was wondering whether we at St George’s might form the basis of a feature. The Church of England at work in modern London.’ Derek’s nose twitched. ‘Old wine in new bottles, one might say.’

‘Amazing, when you think about it.’ Howell grinned at them. ‘Here we are, in an increasingly godless society, but Joe Public just can’t get enough of the good old C of E.’

‘I don’t know if I’d agree with you there, Frank.’ Derek flashed his teeth in a conciliatory smile. ‘Sometimes I think we are not as godless as some of us like to think. Attendance figures are actually increasing – I can find you the statistic, if you want. You have to hand it to the Evangelicals, they have turned the tide. Of course, at St George’s we try to have something for everyone – a broad, non-sectarian approach. We see ourselves as –’

‘You’re doing a fine job, all right.’ Howell kept his eyes on Sally. ‘But at the end of the day, what sells a feature is human interest. It’s the people who count, eh? So maybe we could have a chat sometime.’ He glanced round the little circle of faces. ‘With all of you, that is.’

‘Delighted,’ Derek replied for them all. ‘I –’

‘Good. I’ll give you a ring then, set something up.’ Howell glanced at his watch. ‘Good Lord – is that the time? Must love you and leave you.’

Derek watched him go. ‘Frank was very helpful over the conversion of the Lady Chapel,’ he murmured to Sally, patting her arm. ‘He did a piece on the opening ceremony. We had the bishop, you know.’ Suddenly he stood on tiptoe, and waved vigorously at his wife. ‘There’s Margaret – I know she wanted a word with you, Sally. I think she may have found you a baby-sitter. She’s not one of ours, but a lovely woman, all the same. Utterly reliable, too. Her name’s Carla Vaughan.’

On the way home to Hercules Road, Michael and Sally conducted an argument in whispers in the front of the car while Lucy, strapped into the back seat, sang along with ‘Puff the Magic Dragon’ on the stereo. It was not so much an argument as a quarrel with gloves on.

‘Aren’t we going rather fast?’ Sally asked.

‘I didn’t realize we were going to be so late.’

‘Nor did I. The service took longer than I expected, and –’

‘I’m worried about lunch. I left it on quite high.’

Sally remembered all the meals which had been spoiled because Michael’s job had made him late. She counted to five to keep her temper in check.

‘This Carla woman, Sal – the child minder.’

‘What about her?’

‘I wish we knew a bit more.’

‘She sounds fine to me. Anyway, I’ll see her before we decide.’

‘I wish –’

‘You wish what?’

He accelerated through changing traffic lights. ‘I wish she wasn’t necessary.’

‘We’ve been through all this, haven’t we?’

‘I suppose I thought your job might be more flexible.’

‘Well, it’s not. I’m sorry but there it is.’

He reacted to her tone as much as to her words. ‘What about Lucy?’

‘She’s your daughter too.’ Sally began to count to ten.

‘I know. And I know we agreed right from the start we both wanted to work. But –’

Sally reached eight before her control snapped. ‘You’d like me to be something sensible like a teacher, wouldn’t you? Something safe, something that wouldn’t embarrass you. Something that would fit in with having children. Or better still, you’d like me to be just a wife and mother.’

‘A child needs her parents. That’s all I’m saying.’

‘This child has two parents. If you’re so concerned –’

‘And what’s going to happen when she’s older? Do you want her to be a latchkey kid?’

‘I’ve got a job to do, and so have you. Other people manage.’

‘Do they?’

Sally glanced in the mirror at the back of the sun visor. Lucy was still singing along with a robust indifference to the tune, but she had Jimmy pushed against her cheek; she sensed that her parents were arguing.

‘Listen, Michael. Being ordained is a vocation. It’s not something I can just ignore.’

He did not reply, which fuelled her worst fears. He used silence as a weapon of offence.

‘Anyway, we talked about all this before we married. I know the reality is harder than we thought. But we agreed. Remember?’

His hands tightened on the steering wheel. ‘That was different. That was before we had Lucy. You’re always tired now.’

Too tired for sex, among other things: another reason for guilt. At first they had made a joke of it, but even the best jokes wore thin with repetition.

‘That’s not the point.’

‘Of course it’s the point, love,’ he said. ‘You’re trying to do too much.’

There was another silence. ‘Puff the Magic Dragon’ gave way to ‘The Wheels on the Bus’. Lucy kicked out the rhythm on the back of Sally’s seat, attention-seeking behaviour. This should have been a time of celebration after Sally’s first service at St George’s. Now she wondered whether she was fit to be in orders at all.

‘You’d rather I wasn’t ordained,’ Sally said to Michael, voicing a fear rather than a fact. ‘In your heart of hearts, you think women clergy are unnatural.’

‘I never said that.’

‘You don’t need to say it. You’re just the same as Uncle David. Go on, admit it.’

He stared at the road ahead and pushed the car over the speed limit. Mentioning Uncle David had been a mistake. Mentioning Uncle David was always a mistake.

‘Come on.’ Sally would have liked to shake him.

‘Talk to me.’

They finished the journey in silence. In an effort to use the time constructively, Sally tried to pray for the old woman who had cursed her. She felt as if her prayers were falling into a dark vacuum.

‘Your will be done,’ she said again and again in the silence of her mind; and the words were merely sounds emptied of meaning. It was as if she were talking into a telephone and not knowing whether the person on the other end was listening or even there at all. She tried to persuade herself that this was due to the stress of the moment. Soon the stress would pass, she told herself, and normal telephonic reception would be restored. It would be childish to suppose that the problem was caused by the old woman’s curse.

‘Shit,’ said Michael, as they turned into Hercules Road. Someone had usurped their parking space.

‘It’s all right,’ Sally said, hoping that Lucy had not heard. ‘There’s a space further up.’

Michael reversed the Rover into it, jolting the nearside rear wheel against the kerb. He waited on the pavement, jingling his keys, while Sally extracted Lucy and her belongings.

‘What’s for lunch?’ Lucy demanded. ‘I’m hungry.’

‘Ask your father.’

‘A sort of lamb casserole with haricot beans.’ Michael tended to cook what he liked to eat.

‘Yuk. Can I have Frosties instead?’

Their flat was in a small, purpose-built block dating from the 1930s. Michael had bought it before their marriage. It was spacious for one person, comfortable for two and just large enough to accommodate a small child as well. As Sally opened the front door, the smell of burning rushed out to greet them.

‘Shit,’ Michael said. ‘And double shit.’

Before Lucy was born, Sally and Michael Appleyard had decided that they would not allow any children they might have to disrupt their lives. They had seen how the arrival of children had affected the lives of friends, usually, it seemed, for the worse. They themselves were determined to avoid the trap.

They had met through Michael’s job, almost six years before Sally was offered the Kensal Vale curacy. Michael had arrested a garage owner who specialized in selling stolen cars. Sally, who had recently been ordained as a deacon, knew his wife through church and had responded to a desperate phone call from her. The apparent urgency was such that she came as she was, in gardening clothes, with very little make-up and without a dog collar.

‘It’s a mistake,’ the woman wailed, tears streaking her carefully made-up face, ‘some ghastly mistake. Or someone’s fitted him up. Why can’t the police understand?’

While the woman alternately wept and raged, Michael and another officer had searched the house. It was Sally who dealt with the children, talked to the solicitor and held the woman’s hand while they asked her questions she couldn’t or wouldn’t answer. At the time she took little notice of Michael except to think that he carried out a difficult job with more sensitivity than she would have expected.

Three evenings later, Michael arrived out of the blue at Sally’s flat. On this occasion she was wearing her dog collar. Ostensibly he wanted to see if she had an address for the wife, who had disappeared. On impulse she asked him in and offered him coffee. At this second meeting she looked at him as an individual and on the whole liked what she saw: a thin face with dark eyes and a fair complexion; the sort of brown hair that once had been blond; medium height, broad shoulders and slim hips. When she came into the sitting room with the coffee she found him in front of the bookcase. He did not comment directly on its contents or on the crucifix which hung on the wall above.

‘When were you ordained?’

‘Only a few weeks ago.’

‘In the Church of England?’

She nodded, concentrating on pouring the coffee.

‘So that means you’re a deacon?’

‘Yes. And that’s as far as I’m likely to get unless the Synod votes in favour of women priests.’

‘A deacon can do everything a priest can except celebrate Communion: is that right?’

‘More or less. Are you –?’

‘A practising Christian? I’m afraid it’s more theory than practice. My godfather’s a priest.’

‘Where?’

‘He lives in Cambridge now. He’s retired. He used to teach at a theological college in the States.’ Michael sipped his coffee. ‘I doubt if Uncle David approves of the ordination of women.’

‘Many older priests find it hard to accept. And younger ones, too, for that matter. It’s not easy for them.’

They went on to talk of other things. As he was leaving, he paused in the doorway and asked her out to dinner. The invitation surprised her as much (he later admitted) as it surprised him. She refused, but he kept on asking until she accepted, just to get rid of him.

Michael took her to a Chinese restaurant in Swiss Cottage. For most of the time he encouraged her to talk about herself, either evading or returning short answers to the questions she lobbed in return. She told him that she had left her job as a careers adviser in order to go to theological college. Now she was ordained, she had little chance of finding a curacy in the immediate future, all the more so because her father was ill and she did not want to move too far away from him.

‘Besides, a lot of dioceses have no time for women deacons.’

Michael pushed the dish of roast duck towards her. ‘If you’re a deacon – or a priest – well, that has to come first, I suppose? It has to be the most important thing in life, your first allegiance.’

‘Of course.’

‘So where do people fit in? I know you’re not married, but do you have a boyfriend? And what about children? Or would God be more important?’

‘Are you always like this?’

‘Like what?’

‘So pushy.’

‘I’m not usually like this at all.’

She bent over her plate, knowing her thick hair would curtain her face. In those days she had worn it long, and gloried in it.

‘You’re not celibate, are you?’ he asked.

‘It’s nothing to do with you.’

‘Yes, it is.’

‘As it happens, no. But it’s still nothing to do with you.’

Three months later they were married.

It was ridiculous, Sally told herself, to read significance into the malicious ramblings of an unhappy woman. To see them as a portent would be pure superstition. Yet in the weeks that followed Sally’s first service at St George’s, the old woman was often in her mind. The memory of what she had said was like a spreading stain. No amount of rubbing would remove it.

May God damn you and yours.

When Sally had been offered the curacy at Kensal Vale, it had seemed almost too good to be true, an answer to prayer. Although she was not personally acquainted with Derek Cutter, the vicar of St George’s, his reputation was impressive: he was said to be a gifted and dedicated parish priest who had breathed new life into a demoralized congregation and done much good in the parish as a whole.

The timing had seemed right, too. Sally’s father had died the previous winter, bringing both sorrow and an unexpected sense of liberation. Lucy was ready to start school. Sally could at last take a full-time job with a clear conscience. And Kensal Vale was geographically convenient: she could walk from Hercules Road to St George’s Vicarage in forty minutes and drive it in much less, traffic permitting. The only drawback had been Michael’s lack of enthusiasm.

‘What about Lucy?’ he had asked in an elaborately casual voice when she mentioned the offer to him. ‘She won’t be at school all the time.’

‘We’ll find a child minder. It could actually do her good. She needs more stimulation than she gets at home.’

‘Maybe you’re right.’

‘Darling, we’ve discussed all this.’ Not once, Sally thought, but many times. ‘I was never going to be the sort of mother that stays at home all day to iron the sheets.’

‘Of course not. And I’m sure Lucy’ll be fine. But are you sure Kensal Vale’s a good idea?’

‘It’s just the sort of parish I want.’

‘Why?’

‘It’s a challenge, I suppose. More rewarding in the end. Besides, I want to show I can do it, that a woman can do it.’ She glared at him. ‘And I need the stimulation, too. I’ve been freewheeling for far too long.’

‘But have you thought it through? I wouldn’t have said that Kensal Vale’s particularly safe these days.’ He hesitated. ‘Especially for a woman.’

‘I’ll cope,’ Sally snapped. ‘I’m not a fool.’ She watched his mouth tightening and went on in a gentler voice, ‘In any case, jobs like this don’t grow on trees. If I turn this down, I may not be offered another for years. And I need to have experience before I can be priested.’

He shrugged, failing to concede the point, and turned the discussion to the practical details of the move. He was unwilling to endorse it but at least he had not opposed it.

As summer slipped into autumn, Sally began to wonder if Michael might have been right. She was sleeping badly and her dreams were going through a patch of being uncomfortably vivid. The work wasn’t easy, and to make matters worse she seemed to have lost her resilience. In the first week, she was rejected by a dying parishioner because she was a woman, a smartly dressed middle-aged man spat on her in the street, and her handbag was stolen by a gang of small boys armed with knives. Similar episodes had happened before, but previously she had been able to digest them with relative ease and consign them to the past. Now they gave her spiritual indigestion. The images stayed with her: the white face on the pillow turning aside from the comfort she brought; the viscous spittle gleaming on her handkerchief; and, hardest of all to forget, the children, some no more than five years older than Lucy, circling her in their monstrous game with knives in their hands and excitement in their faces.

Nothing went right at home, either. Michael had retreated further into himself since the squabble on the way back from church and the subsequent discovery that Sunday lunch had turned into a burnt offering. There were no open quarrels but the silences between them grew longer. It was possible, Sally thought, that the problem had nothing to do with her – he might be having a difficult time at work.

‘Everything’s fine,’ he replied when she asked him directly, and she could almost hear the sound of the drawbridge rising and the portcullis descending.

Sally persevered. ‘Have you seen Oliver lately?’

‘No. Not since his promotion.’

‘That’s great. When did it happen?’

‘A few weeks back.’

Why hadn’t Michael told her before? Oliver Rickford had been his best man. Like Michael, he had been a high-flier at Hendon police college. They had not worked together since they had been constables, but they still kept in touch.

‘Why’s he been made up to inspector and not you?’

‘He says the right things in committee meetings.’ Michael looked at her. ‘Also he’s a good cop.’

‘We must have him and Sharon over for supper. To celebrate.’ Sally disliked Sharon. ‘Tuesdays are usually a good evening for me.’

Michael grunted, his eyes drifting back to the newspaper in front of him.

‘I suppose we should ask the Cutters sometime, too.’

‘Oh God.’ This time he looked up. ‘Must we?’

Their eyes met and for an instant they were united by their shared dislike of the Cutters. The dislike was another of Sally’s problems. As the weeks went by, she discovered that Derek Cutter preferred to keep her on the sidelines of parish work. He made her feel that wearing a deacon’s stole was the clerical equivalent of wearing L-plates. She suspected that in his heart of hearts he was no more a supporter of women clergy than Michael’s Uncle David. At least David Byfield made his opposition perfectly clear. Derek Cutter, on the other hand, kept his carefully concealed. She attributed her presence in his parish to expediency: the archdeacon was an enthusiastic advocate of the ordination of women, and Derek had everything to gain by keeping on the right side of his immediate superior. He liked to keep on the right side of almost everyone.

‘Lovely to see you,’ Derek said to people when he talked to them after a service or at a meeting or on their doorsteps. ‘You’re looking blooming.’ And if he could, he would pat them, young or old, male or female. He liked physical contact.

‘It’s not enough to love each other,’ he wrote in the parish magazine. ‘We must show that we do. We must wear our hearts on our sleeves, as children do.’

Derek was fond of children, though he preferred to look resolutely on the sunny side of childhood. This meant in effect that his benevolent interest was confined to children under the age of seven. Children grew up quickly in Kensal Vale and the area had an extensive population of little criminals. The picture of him in the Parish Room showed him beaming fondly at a photogenic baby in his arms. In his sermon on Sally’s second Sunday at St George’s he quoted what was evidently a favourite text.

‘Let the children come to me, Jesus told his disciples. Do not try to stop them. For the kingdom of God belongs to such as these. Mark ten, fourteen.’

There should be more to being a vicar, Sally thought, than a fondness for patting people, a sentimental attachment to young children and a range of secular skills that might have earned him a decent living in public relations or local government.

Sally knew that she was being unfair to Derek. As an administrator he was first class. The parish’s finances were in good order. The church was well-respected in the area. There was a disciplined core congregation of over a hundred people. As a parish, St George’s had a sense of community and purpose: Derek deserved much of the credit for this. And some of the credit must also be due to his wife. The Cutters, as Derek was fond of telling people, were a team.

Margaret Cutter was a plump woman who looked as if she had been strapped into her clothes. She had grey hair styled to resemble wire wool. Her kindness was the sort that finds its best expression in activity, preferably muscular. She invited Sally for coffee at the Vicarage on the Tuesday after Sally’s first service at St George’s. They sat in a small, overheated sitting room whose most noteworthy features were the bars on the window and the enormous photocopying machine behind the sofa. On top of the television set stood a toy rabbit with soft pink fur and a photograph of Derek and Margaret on their wedding day. Sally thought that she looked older than her husband.

‘Just us two girls,’ Margaret said, offering Sally a plate of digestive biscuits, which proved to be stale. ‘I thought it would be nice to have a proper chat.’ The chat rapidly turned into a monologue. ‘It’s the women who are the real problem. You just wouldn’t believe the way they throw themselves at Derek.’ The tone was confiding, but the dark eyes flickered over Sally as if measuring her for a shroud. ‘Of course, he doesn’t see it. But isn’t that men all over? They’re such fools where women are concerned. That’s why they need us girls to look after them.’ Here she inserted a pause which gave Sally ample time to realize that, astonishing as it might seem, Margaret was warning her that Derek was off limits as a potential object of desire. ‘I knew when I married him that he was going to be a full-time job. I used to be a lecturer, you know, catering was my subject; they begged me to stay but I said, “No, girls, I only wish I could but I have to think of Derek now.” Well, that’s marriage, isn’t it, for better or for worse, you have to give it top priority or else you might as well not do it.’ She stroked her own forearm affectionately. ‘You must find it very hard, Sally, what with you both working and having the kiddie to think of as well. Still, I expect your Lucy’s grown used to it, eh? Such a sweet kiddie. In some ways it’s a blessing that Derek and I haven’t had children. I honestly don’t think we would have had time to give them the love and attention they need. But that reminds me, I promised to give you Carla Vaughan’s phone number. I must admit she’s not to everyone’s taste, but Derek thinks very highly of her. He sees the best in everyone, Derek does. You do realize that Carla’s a single parent? Two little kiddies, with different fathers and I don’t think she was married to either. Still, as Derek says, who are we to cast the first stone? Did he mention she likes to be paid in cash?’

The following day, Wednesday, Sally took Lucy to meet Carla. She lived in a small terraced house which was almost exactly halfway between St George’s and Hercules Road. Half West Indian and half Irish, she had an enormous mop of red curly hair which she wore in a style reminiscent of a seventeenth-century periwig. The house seethed with small children and the noise was formidable. Carla’s feet were bare, and she was dressed in a green tanktop and tight trousers which revealed her sturdy legs and ample behind; she was not a woman who left much to the imagination.

Carla swept a bundle of magazines from one of the chairs. ‘Do you want a Coke or something? And what about you, Lucy?’

Lucy shook her head violently. She kept close to her mother and stared round-eyed at the other children, who ignored her. Carla took two cans from the refrigerator and gave one to Sally.

‘Saves washing up. You don’t mind, do you?’ She stared with open curiosity at the dog collar. ‘What should I call you, by the way? Reverend or something?’

‘Sally, please. What a lovely big room.’

‘One of my fellas did it for me. He was a builder. I told him to knock down all the walls he could without letting the house fall down. And when he’d finished I gave him his marching orders. I’m through with men. If you ask me, you’re better off without them.’ She leaned forward and lowered her voice slightly. ‘Sex. You can keep it. Mind you, men have their uses when you need a bit of DIY.’

Sally glanced round the room, ostensibly admiring the decor. She noticed that most of the horizontal surfaces held piles of washing, disposable nappies, toys, books, empty sweet packets and video tapes. The back door was open and there was a sunlit yard beyond with a small swing and what looked like a sandpit. Sally thought that the place was fundamentally clean under the clutter and that the children seemed happy; she hoped this was not wishful thinking.

While she and Carla discussed the arrangements, Lucy feigned an interest in the twenty-four-inch television set, which was glowing and mumbling in a recess where there had once been a fireplace; she pretended to be absorbed in an episode from Thomas the Tank Engine, a programme she detested.

‘Why don’t you leave her for an hour or two? Trial run, like.’

Sally nodded, ignoring the sudden surge of panic. Lucy lunged at her arm.

‘You just go, honey.’ Carla detached Lucy with one hand and gave Sally a gentle push with the other. ‘Have you ever made gingerbread robots with chocolate eyes?’ she asked Lucy.

The crying stopped for long enough for Lucy to say, ‘No.’

‘Nor have I. And we won’t be able to unless you can help me find the chocolate.’

Sally slipped out of the house. She hated trusting Lucy to a stranger. But whatever she did, she would feel guilty. If you had to list the top ten attributes of modern motherhood, then guilt would be high up there in the top three.

Sally Appleyard could not say when she first suspected that she was being watched. The fear came first, crawling slowly into her life when she was not looking, masquerading as a sense of unease. Her dreams filled with vertiginous falls, slowly opening doors and the sound of footsteps in empty city streets.

Rightly or wrongly she associated the change in the emotional weather with the appearance in mid-September of Frank Howell’s feature in the Evening Standard. In his idiosyncratic way the balding cherub had done St George’s proud. Here, Sally was interested to learn, was the real Church of England. Two photographs accompanied the piece: one of Derek equipped with dog collar, denim jacket and Afro-Caribbean toddler; the other of Sally. In the text Howell described the incident at Sally’s first service.

‘Pity he had to choose St George’s,’ Michael said when he saw the article.

‘Why?’

‘Because now all the nutters will know you’re there.’

She laughed at him but his words lingered in her memory. There was no shortage of rational explanations for what she felt. She was tired and worried. It was not unnatural, particularly for a woman, to equate a sense of unease with being watched. She knew that a solitary and reasonably attractive woman was vulnerable in parts of the parish. To a certain type of male predator her profession might even add to her allure. Perhaps Michael had inadvertently planted the idea in her mind. Besides, to some extent she really was under observation: she was still a novelty in Kensal Vale: the woman with the dog collar was someone to stare at, to point out, sometimes to laugh at, and occasionally to abuse.

She-devil. Blasphemer against Christ. Apostate. Impious bitch. Whore of Babylon. Daughter of Satan.

One evening near the end of the month she was later home than expected. Michael was watching from the window.

‘Where the hell were you?’ he demanded as he opened the door to her. ‘Do you know what time it is?’

‘I’m sorry,’ she snapped, her mind still full of the room she had left, with the bed, the people, the smells and the chattering television and the view from a high window of Willesden Junction beneath an apocalyptic western sky. ‘Someone was dying and there wasn’t a phone.’

‘You should have sent someone out, then. I’ve phoned the Cutters, the hospitals, the police.’

His face crumpled. She put her arms around him. They clung together by the open door. Michael’s hands stroked her back and her thighs. His mouth came down on hers.

She craned her head away. ‘Michael –’

‘Hush.’

He kissed her again and this time she found herself responding. She tried to blot out the memory of the room with the high window. One of his hands slipped round to the front of her jeans. She shifted back to allow his fingers room to reach the button of the waistband.

‘Mummy,’ Lucy called. ‘I’m thirsty.’

‘Oh God.’ Michael drew back, grimacing at Sally. ‘You go and see her, love. I’ll get the drink.’

The following evening, he came home with a personal alarm and a mobile phone.

‘Are you sure I need all these?’

‘I need you to have them.’

‘But the cost. We –’

‘Bugger the cost, Sal.’

She smiled at him. ‘I’m no good with gadgets.’

‘You will be with these.’

She touched his hand. ‘Thank you.’

The alarm and the phone helped at least for a time. The fact that Carla could now contact her at any time was also reassuring. But the fear returned, a familiar devil. Feeling watched was a part of it. So too was a sense of the watcher’s steady, intelligent malevolence. Behind the watching was a fixed purpose.

But there was nothing, or very little, to pin it to. The evidence was skimpy, almost invisible, and capable of innocent interpretations: a small, pale van which one afternoon followed her car round three successive left turns; someone in a long raincoat walking down Hercules Road late at night and glancing up at the windows of the flat; warm breath on the back of her neck in a crowd swirling down the aisle of a supermarket; Lucy’s claim that a man had winked at her in the library when she went there with Carla and the other children. As to the rest, what did it amount to but the occasional shiver at the back of the neck, the sense that someone might be watching her?

To complicate matters, Sally did not trust her instincts. She couldn’t be sure whether the fear was a response to something in the outside world or merely a symptom of an inner disturbance. This was nothing new: since her teens, she had trained herself to be wary of her intuitions partly because she did not understand them and partly because she knew they could be misleading. She lumped them together with the uncomfortably vivid dreams and the moments when time seemed to stand still. They were interesting and disturbing: but there was nothing to show that they were more than freak outbreaks of bioelectrical activity.

The scepticism was doubly necessary at present: she was under considerable strain, in a state which might well induce a certain paranoia. In the end it was a question of degree. Carrying a rape alarm was a sensible precaution against a genuine danger: acting as if she were a potential terrorist target was not.

In November, leaves blew along the pavements, dead fireworks lined the gutters, and mists smelling of exhaust fumes and decaying vegetables softened the outlines of buildings. In November, Uncle David came to lunch.

The ‘Uncle’ was a courtesy title. David Byfield was Michael’s godfather. He had been a friend of his parents and his connection with Michael had survived their deaths and the cooling of his godson’s religious faith. An Anglo-Catholic, he was often addressed as ‘Father Byfield’ by those of the same persuasion. The November lunch in London had become a regular event. In May the Appleyards went to Cambridge for a forbiddingly formal return fixture at the University Arms.

This Saturday was the worst yet. It began badly with an emergency call from Derek, who had gone down with toothache and wanted Sally to take a wedding for him. Sally abandoned the cooking and Lucy to Michael. Neither the service nor the obligatory appearance at the reception did much for her self-esteem. The bride and groom were disgruntled to see her rather than Derek, and the groom’s mother asked if the happy couple would have to have a proper wedding afterwards with a real clergyman.

When Sally returned to Hercules Road she found the meal over, the sink full of dirty plates, the atmosphere stinking of David’s cigarettes and Lucy in tears. Averting his eyes from her dog collar, David stood up to shake hands. Lucy chose this moment to announce that Daddy was an asshole, an interesting new word she had recently picked up at Carla’s. Michael slapped her leg and Lucy’s tears became howls of anguish.

‘You sit down,’ Michael told Sally. ‘I’ll deal with her.’ He towed Lucy away to her room.

David Byfield slowly subsided into his chair. He was a tall, spare man with prominent cheekbones and a limp due to an arthritic hip. As a young man, Sally thought, he must have been very good-looking. Now he was at least seventy, and a lifetime of self-discipline had given his features a harsh, almost predatory cast; his skin looked raw and somehow thinner than other people’s.

‘I’m so sorry not to have been here for lunch,’ Sally said, trying to ignore the distant wails. ‘An unexpected wedding.’

David inclined his head, acknowledging that he had heard.

‘The vicar had to go to casualty. Turned out to be an abscess.’ Why did she have to sound so bright and cheery? ‘Has Lucy been rather a handful?’

‘She’s a lively child. It’s natural.’

‘It’s a difficult age,’ Sally said wildly; all ages were difficult. ‘She’s inclined to play up when I’m not around.’

That earned another stately nod, and also a twitch of the lips which possibly expressed disapproval of working mothers.

‘I hope Michael has fed you well?’

‘Yes, thank you. Have you had time to eat, yourself?’

‘Not yet. There’s no hurry. Do smoke, by the way.’

He stared at her as if nothing had been further from his mind.

‘How’s St Thomas coming along?’

‘The book?’ The tone reproved her flippancy. ‘Slowly.’

‘Aquinas must be a very interesting subject.’

‘Indeed.’

‘I read somewhere that his fellow students called him the dumb ox of Sicily,’ Sally said with a touch of desperation. ‘Do you have a title yet?’

‘The Angelic Doctor.’

Sally quietly lost her temper. One moment she had it under firm control, the next it was gone. ‘Tell me, do you think that a man who was fascinated by the nature of angels has anything useful to say to us?’

‘I think St Thomas will always have something useful to say to those of us who want to listen.’

Not trusting herself to speak, Sally poured herself a glass of claret from the open bottle on the table. She gestured to David with the bottle.

‘No, thank you.’

For a moment they listened to the traffic in Hercules Road and Lucy’s crying, now diminishing in volume.

The phone rang. Sally seized it with relief.

‘Sally? It’s Oliver. Is Michael there?’

‘I’ll fetch him.’

She opened the living room door. Michael was sitting on Lucy’s bed, rocking her to and fro on his lap. She had her eyes closed and her fingers in her mouth; they both looked very peaceful. He looked at Sally over Lucy’s face.

‘Oliver.’

For an instant his face seemed to freeze, as though trapped by the click of a camera shutter. ‘I’ll take it in the bedroom.’

Lucy whimpered as Michael passed her to Sally. In the sitting room, Lucy curled up on one end of the sofa and stared longingly at the blank screen of the television. Sally picked up the handset of the phone. Oliver was speaking: ‘… complaining. You know what that …’ She dropped the handset on the rest.

‘It’s a colleague of Michael’s. I’m afraid it may be work.’

‘I should be going.’ David began to manoeuvre himself forward on the seat of the chair.

‘There’s no hurry, really. Stay for some tea. Anyway, perhaps Michael won’t have to go out.’ Desperate for a neutral subject of conversation, she went on, ‘It’s Oliver Rickford, actually. Do you remember him? He was Michael’s best man.’

‘I remember.’

There was another silence. The subject wasn’t neutral after all: it reminded them both that David had refused to conduct their wedding. According to Michael, he had felt it would be inappropriate because for theological reasons he did not acknowledge the validity of Sally’s orders. He had come to the service, however, and hovered, austere and unfestive, at the reception. He had presented them with a small silver clock which had belonged to his wife’s parents. The clock did not work but Michael insisted in having it on the mantelpiece. Sally stared at it now, the hands eternally at ten to three and not a sign of bloody honey.

Michael came in. She knew from his face that he was going out, and knew too that something was wrong. Lucy began to cry and David said he really should leave before the light went.

The last Friday in November began with a squabble over the breakfast table about who should take Lucy to Carla’s. As the school was closed for In-Service Training, Lucy was to stay with the child minder all day.

‘Can’t you take her this once, Michael? I promised I’d give Stella a lift to hospital this morning.’

‘Why didn’t you mention it before?’

‘I did – last night.’

‘I don’t remember. Stella’s not ill, is she?’

‘They’re trying to induce her daughter. It’s her first. She’s a couple of weeks overdue.’

‘It’s not going to make that much difference if Stella gets there half an hour later, is it?’

‘It’ll be longer than that because I’ll hit the traffic.’

‘I’m sorry. It’s out of the question.’

‘Why? Usually you can –’

Michael pushed his muesli bowl aside with such force that he spilled his tea. ‘This isn’t a usual day.’ His voice was loud and harsh. ‘I’ve got a meeting at nine-fifteen. I can’t get out of it.’

Sally opened her mouth to reply but happened to catch Lucy’s eye. Their daughter was watching them avidly.

‘Very well. I’d better tell Stella.’

She left the room. After she made the phone call she made the beds because she couldn’t trust herself to go back into the kitchen. She heard Michael leaving the flat. He didn’t call goodbye. Usually he would have kissed her. She was miserably aware that too many of their conversations ended in arguments. Not that there seemed to be much time at present even to argue.

On the way to Carla’s, Sally worried about Michael and tried to concentrate on driving. Meanwhile, Lucy talked incessantly. She had a two-pronged strategy. On the one hand she emphasized how much she didn’t want to go to Carla’s today, and how she really wanted to stay at home with Mummy; on the other she made it clear that her future happiness depended on whether or not Sally bought her a conjuring set that Lucy had seen advertised on television. The performance lacked subtlety but it was relentless and in its primitive way highly skilled. What Lucy had not taken into account, however, was the timing.

‘Do be quiet, Lucy,’ Sally snarled over her shoulder. ‘I’m not going to take you to Woolworth’s. And no, we’re not spending all that money on a conjuring set. Not today, and not for Christmas. It’s just not worth it. Overpriced rubbish.’

Lucy tried tears of grief and, when these failed, tears of rage. For once it was a relief to leave her at Carla’s.

The day moved swiftly from bad to worse. Driving Stella to hospital took much longer than Sally had anticipated because of roadworks. Stella was worried about her daughter and inclined to be grumpy with Sally because of the delay; but once at the hospital she was reluctant to let Sally go.

The hospital trip made Sally late for the monthly committee meeting dealing with the parish finances which began at eleven. She arrived to find that Derek had taken advantage of her absence and rushed through a proposal to buy new disco equipment for the Parish Room, a scheme which Sally thought unnecessarily expensive. Despite his victory, Derek was in a bad mood because during the night someone had spray-painted a question on the front door of the Vicarage: IS THERE LIFE BEFORE DEATH?

‘Infuriating,’ he said to Sally after the meeting. ‘So childish.’

‘At least it’s not obscene.’

‘If only they had come and talked to me instead.’

‘There are theological implications,’ she pointed out. ‘You could use it in a sermon.’

‘Very funny, I’m sure.’

He scowled at her. For a moment she almost liked him. Only for a moment. She walked back to her car in the Vicarage car park. It was then that she discovered that she had left her cheque book and a bundle of bills at home. The bills were badly overdue and in any case she wanted to draw cash for the weekend. Skipping lunch, she drove back to Hercules Road where to her surprise she found Michael. He was sitting at his desk in the living room going through one of the drawers. There was a can of lager on top of the desk.

‘What are you doing?’

He glanced at her and she knew at once that their quarrel at breakfast time had not been forgotten or forgiven. ‘I have to check something. All right?’

Sally nodded as curtly as he had spoken. In silence she collected her cheque book and the bills. On her way out, she forced herself to call goodbye. Once she reached the car she discovered that she had managed to leave her phone behind. She didn’t want to go back for it because that would mean seeing Michael again.

She drove miserably back to Kensal Vale. It wasn’t just that she knew that Michael was capable of nursing a grudge for days. She worried that this grudge was merely a symptom of something worse. Perhaps he wanted to leave her and was summoning up the strength to make the announcement. Not that there was much to keep him. Their existence had been reduced to routine drudgeries coordinated by a complicated timetable of draconian ferocity. At the thought of life without him her stomach turned over.

She was down to visit a nursing home for the first part of the afternoon, but when she reached the Vicarage (IS THERE LIFE BEFORE DEATH?) she found a message in Derek’s neat, italic hand.

Tried to reach you on your mobile. Off to see Archdeacon. Margaret at Brownies p.m. Please ring police at KV – Sergeant Hatherly – re attempted suicide. Paint apparently indelible.

She picked up the telephone and dialled the number of the Kensal Vale police station. She was put through to Hatherly immediately.

‘We had this old woman tried to kill herself last night. She’s in hospital now. Still in a coma, I understand. I think she’s one of your lot so I thought we’d better let you know.’

‘What’s her name?’

‘Audrey Oliphant.’

‘I don’t know her.’

‘She probably knows you, Reverend.’ Hatherly used the title awkwardly: like many people inside and outside the Church he wasn’t entirely sure how he should address a woman in holy orders. ‘She’s got a bedsit at twenty-nine Belmont Road. You know it? She’s one of the DSS ones, according to the woman who runs the place. Very religious. Her room’s full of bibles and crucifixes.’

‘What makes you think she’s one of ours?’

‘She had one of your leaflets. Anyway, I’ve checked with the RCs. They don’t know her from Adam.’

Sally pulled a pad towards her and jotted down the details.

‘Took an overdose, it seems. Probably sleeping tablets. According to the landlady, she’s a few bricks short of a load. Used to be in some sort of home, I understand. Now they’ve pushed her out into the community, poor old duck. Poor old community, too.’

‘I’ll ring the hospital and ask if I can see her. I could go via Belmont Road and see if there’s anything she might need.’

‘The landlady’s a Mrs Gunter. I’ll give her a ring if you like. Tell her to expect you. I think she’ll be glad if someone else will take the responsibility.’

That makes two of you, thought Sally.

‘I knew that one was trouble,’ Mrs Gunter said over her shoulder. ‘People like Audrey can’t cope with real life.’ She paused, panting, on the half-landing and stared at Sally with pale, bloodshot eyes. ‘When all’s said and done, a loony’s a loony. You don’t want them roaming round the streets. They need looking after.’

They moved slowly up the last flight of stairs. They were on the top floor of the house. Someone was playing rock music in a room below them. The house smelled of cooking and cigarettes. Mrs Gunter stopped outside one of the three doors on the top landing and fiddled with her keyring.

‘I phoned that woman at Social Services this morning. I’m sorry, I said, I can’t have her back here. It’s not on, is it? They pay me to give her a room and her breakfast. I’m not a miracle-worker.’ Mrs Gunter darted a hostile glance at Sally. ‘I leave the miracles to you.’

She unlocked the door and pushed it open. The room was small and narrow with a sloping ceiling. The first thing Sally noticed was the makeshift altar. The top of the chest of drawers was covered with a white cloth on which stood a wooden crucifix flanked by two brass candlesticks. The crucifix stood on a stepped base and was about eight inches high. The figure of Christ was made of bone or ivory.

‘If you met her on the stairs she was always muttering to herself,’ Mrs Gunter said. ‘For all I know she was praying.’

The sash window was six inches open at the top and overlooked the back of the house. The air was fresh, damp and very cold. The single bed was unmade. Sally stared at the surprisingly small indentation where Audrey Oliphant had lain. There were no pictures on the walls. A portable television stood on the floor beside the wardrobe; it had been unplugged, and the screen was turned to the wall. In front of the window was a table and chair. Against the wall on the other side of the wardrobe was a spotlessly clean washbasin.

‘She left a note.’ Mrs Gunter twisted her lips into an expression of disgust. ‘Said she was sorry to be such a trouble, and she hoped God would forgive her.’

‘How did you find her?’

‘She didn’t come down to breakfast. I knew she hadn’t gone out. Besides, it was time for her to change her sheets. And I wanted to talk to her about the state she leaves the bathroom.’

They found a leather-and-canvas bag with a broken lock in the wardrobe. As they packed it, Mrs Gunter kept up a steady flow of complaint. Meanwhile her hands deftly folded faded nightdresses and smoothed away the wrinkles from a tweed skirt.

‘She’s run out of toothpaste, the silly woman. I’ve got a bit left in a tube downstairs. She can have that. I was going to throw it away.’

‘Do you know where she went to church?’

‘I don’t know if she did. Or nowhere regular. If you ask me, this was her church.’

Sally picked up the three books on the bedside table. There was no other reading material in the room. All of them were small and well-used. Sally glanced at them as she dropped them in the bag. First there was a holy bible, in the Authorized Version. Next came a book of common prayer, inscribed ‘To Audrey, on the occasion of her First Communion, 20th March 1937, with love from Mother’.

The third book was Sir Thomas Browne’s Religio Medici, a pocket edition with a faded blue cloth cover. Sally opened the book at the page where there was a marker. She found a faint pencil line in the margin against one sentence. ‘The heart of man is the place the Devils dwell in: I feel sometimes a Hell within my self; Lucifer keeps his Court in my breast, Legion is revived in me.’

As Sally read the words her mood altered. The transition was abrupt and jerky, like the effect of a mismanaged gear change on a car’s engine. Previously she had felt solitary and depressed. Now she was on the edge of despair. What was the use of this poor woman living her sad life? What was the use of Sally’s attempt to help?

The despair was a familiar enemy, though today it was more powerful than usual. Its habit of descending on her was one of those inconvenient facts which she had to live with, like the bad dreams and the absurd moments when time seemed to stop; just another outbreak of freak weather in the mind. While she was driving to the hospital she tried to pray but she could not shift the mood. Her mind was in darkness. She felt the first nibbles of panic. This time the state might be permanent.

On one level Sally continued to function normally. She parked the car and went into the hospital. In the reception area she exchanged a few words with a physiotherapist who sometimes came to St George’s. She took the lift up to the seventh floor. A staff nurse was slumped over a desk in the ward office with a pile of files before her. Sally tapped on the glass partition. The nurse looked at the dog collar and rubbed her eyes. Sally asked for Audrey Oliphant.

‘You’re too late. Died about forty minutes ago.’

‘What happened?’

The nurse shrugged – not callous so much as weary. ‘The odds are that her heart just gave way under the strain. Do you want to see her?’

They had given Audrey Oliphant a room to herself at the end of the corridor. The sheet had been pulled up to the top of the bed. The staff nurse folded it back.

‘Did you know her?’

Sally stared at the dead face: skin and bone, stripped of personality; no longer capable of expressing anger or unhappiness. ‘I saw her once in church. I didn’t know her name.’

On the bed lay the woman who had cursed her.

Sally found it difficult not to feel that she was in one respect responsible for Audrey Oliphant’s death. It made it worse that the old woman now had a name. Perhaps if Sally had tried to trace her, Audrey Oliphant might still be alive. The pressure must have been enormous for a woman of that age and background to kill herself.

She phoned Mrs Gunter from the hospital concourse and gave her the news.

‘Best thing for all concerned, really.’

Sally said nothing.

‘No point in pretending otherwise, is there?’ Mrs Gunter sniffed. ‘And now I suppose I’ll have to sort out her things. You’d think she’d be more considerate, wouldn’t you, being a churchgoer.’

Sally said she would return Audrey Oliphant’s bag.

‘Hardly seems worth bothering. Audrey said she hadn’t got no relations. Not that they’d want her stuff. Nothing worth having, is there? Simplest just to put it out with the rubbish. Except Social Services would go crazy. Crazy? We’re all crazy.’

During the afternoon the despair retreated a little. It was biding its time. Sally visited the nursing home. She let herself into St George’s and tried to pray for Audrey Oliphant. The church felt cold and alien. The thoughts and words would not come. She found herself reciting the Lord’s Prayer in the outmoded version which she had not used since she was a child. The dead woman had probably prayed in this way: ‘Our Father, which art in heaven.’ The words lay in her mind, heavy and indigestible as badly cooked suet.

Halfway through, she glanced at her watch and realized that if she wasn’t careful she would be late picking up Lucy. She gabbled the rest and left the church. The Vicarage was empty but she left a note for Derek, who was still enjoying himself with the archdeacon.

It was raining, sending slivers of gold through the halos of the streetlamps. As Sally drove, she wondered whether Lucy had forgotten the conjuring set. It was unlikely. For one so young she could be inconveniently tenacious.

Sally left the car double-parked outside Carla’s house and ran through the rain to the front door. The door opened before she reached it.

Carla was on the threshold, her hands outstretched, her face crumpled, her eyes squeezed into slits and the tears slithering down her dark cheeks. The big living room behind her was in turmoil: it seethed with adults and children; and the television shimmered in the fireplace. A uniformed policewoman put her hand on Carla’s arm. She said something but Sally didn’t listen.

Michael was there too, talking angrily into the phone, slashing his free hand against his leg to emphasize what he was saying. He stared in Sally’s direction but seemed not to register her presence: he was looking past her at something unimaginable.

2 (#ulink_a9e2722b-3bd8-566b-9142-8dfeb653435f)

‘I am naturally bashful; nor hath conversation, age, or travel, been able to effront or enharden me …’

Religio Medici, I, 40

Eddie called her Angel and so had the children. He knew the name pleased her but not why. Lucy Appleyard refused to call Angel anything at all. In that, as in so much else, Lucy was different.

Lucy Philippa Appleyard was unlike the others even in the way Angel chose her. It was only afterwards, of course, that Eddie began to suspect that Angel had a particular reason for wanting Lucy. Yet again he had been manipulated. The questions were: how much, how far back did it go – and why?