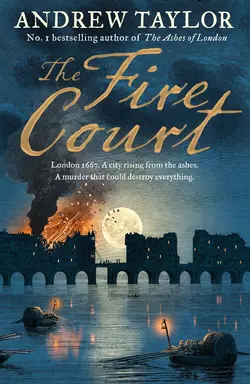

The Fire Court: A gripping historical thriller from the bestselling author of The Ashes of London

Andrew Taylor

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 2023.17 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: From No.1 bestselling author Andrew Taylor comes the sequel to the phenomenally successful The Ashes of LondonA time of terrible danger…The Great Fire has ravaged London. Now, guided by the Fire Court, the city is rebuilding, but times are volatile and danger is only ever a heartbeat away.Two mysterious deaths…James Marwood, a traitor’s son, is thrust into this treacherous environment when his father discovers a dead woman in the very place where the Fire Court sits. The next day his father is run down. Accident? Or another murder…?A race to stop a murderer…Determined to uncover the truth, Marwood turns to the one person he can trust – Cat Lovett, the daughter of a despised regicide. Then comes a third death… and Marwood and Cat are forced to confront a vicious killer who threatens the future of the city itself.